Camden C. Danielson

Do you know your people? And do you love them?

Mother Teresa

Address to Indian HR Executives

The global environment is increasing the degree of complexity for organizations operating anywhere in the world. With it arises the need for a different kind of inquiry operating within our lives and organizations. The requirement for greater openness to uncertainty will challenge our sense of purpose, identity, and self-efficacy. The founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung, noted:

“The definiteness and directedness of the conscious mind are extremely important acquisitions which humanity has bought at a very heavy sacrifice, and which in turn have rendered humanity the highest service…Civilized life today demands concentrated, directed conscious functioning, and this entails the risk of [reduced adaptive capacity]” (CW 8: 135, 139).

Why has the highly directed conscious process of modern society reduced our adaptive capacity? Jung responds, “the quality of directedness makes for the inhibition or exclusion of all those [unrealized dimensions of the self] which appear to be, or really are, incompatible with it” (CW 8: 136). In other words, our worldview determines what is rational and that bias is based upon what is familiar and not what is unknown.

Leaders, like the organizations for whom they provide guidance and direction, face the challenge of adapting their understanding of the world when their worldview is no longer sufficient to solving the problems they face. Initially, they may deny that anything is wrong or needs to change or they may acknowledge that something is wrong if it means it is someone else’s problem. Eventually, they may accept their own need to do something, but it can take the form of extending current competencies. While the admission of personal responsibility for action is commendable, there is a tendency to merely reinforce what is known with all of the underlying assumptions still in tact (what is meant by horizontal as opposed to vertical development). The classic example is undertaking organizational restructuring as a solution when something much larger needs to be addressed.

Eventually, a leader may have “a moment of clarity” in the recognition that no known means exists for solving the problems he or she face. It is a disorienting experience to realize that control is an illusion, but it can also be a catalytic event leading to a new kind of inquiry. Alfred North Whitehead wrote “mankind is driven forward by dim apprehensions of things too obscure for its existing language” (Pirsig 133). Beyond the known lies the unexplored and as more risks to organization adaptation arise, so increases the evolutionary impulse to bridge current practices by addressing unrealized potential.

In roles working between the lessons of the past and an indistinct future, global leaders must operate in the gray space of unformed understanding. Rather than viewing their particular orientation as a superior apprehension, they face the challenge of finding a third space to hold different worldviews or operating logics that often clash like fault lines. In this space much is risked, but much is possible in the transcendence of differences. But how is that to be done and who are the individuals who can facilitate this bridge between a current worldview and “things too obscure for [our] existing language?”

Leadership Characteristics

This article describes four leadership characteristics of 17 individuals whose common denominator was their participation in three or more programs at The Monroe Institute (TMI). The Institute, founded by Robert A. Monroe, uses a patented, guided auditory technology for facilitating deep meditative states through a process he described as hemispheric synchronization (hemi-sync). Appendix 1 provides a brief description of the hemi-sync process written by Monroe’s biographer, Ronald Russell.

The leadership profile of the group, based on a multi-rater leadership assessment instrument (The Leadership Circle Profile), was comparable to those in an extraordinary leader group (Danielson, 2010). Further, these 17 individuals were a representative sample of more than 300 in a previous study and who likewise had attended three or more programs at TMI. They had shown statistically significant differences in life satisfaction and self-efficacy compared to a similar number of individuals who had only attended one program (Danielson, 2008). In both of these studies the objective was to understand the effects of long-term participation in these programs, rather than to replicate previous research on either the efficacy of the technology or the nature of the meditative or focused states of consciousness. What I discovered is relevant to the question of adaptive capacity needed to address the complexity in the global environment today.

Let me set the stage further by noting that the individuals I interviewed had a mixed background in terms of their formal development as leaders. All had moved through a wide range of careers—some in Fortune 100 companies, some in small businesses, some in non-profits, some in government agencies—but most were now running their own businesses or professional services groups. So it was not surprising that each interview revealed something new and often unexpected. The key to understanding the pattern I observed occurred in one of my final interviews where I heard a similar sentiment expressed about his experience at the institute:

“[It] got me outside of my box; got me outside of various traps, constructs, and concepts that had bogged me down. I simply got to a bigger state, a larger perspective…In fact, [these programs] for me are really about the unexpected. That is why I go back, for the unexpected.”

This struck a cord with me so I probed a little deeper and asked what he meant:

“I am more conscious now. I get these little epiphanies such as “having a higher consciousness isn’t about possessing yogic powers, but about being conscious on multiple levels, multiple dimensions and making conscious choices…It is being more aware, being more awake.”

Participant L

This was a summary statement of my experience with the participants in this study. I was present to individuals who were striving to be conscious on multiple levels. In order to achieve that they were not merely open to the unexpected; they expected the unexpected. Alive within an infinite universe that is also alive, they were yet distinctive in their abilities to give voice to what they experienced. The interchange of the two—the life around them and the life within them—was an ongoing process of creation, change, and growth. “Formation, Transformation/Eternal Mind’s eternal recreation,” is how Goethe captured it (79). It closely parallels what I understand Kegan and Lahey to mean when they use the term “self-transforming mind” (19).

Knowledge and Mental Development

Kegan and Lahey’s model of human development is built upon the Aristotelian precept that by nature we desire knowledge. Call it the other half of Goethe’s vision of the eternal mind where our ego-based mind desires to know, to understand, and to make meaning of our experience. Within this context, knowledge is a dynamic relationship between the knower and the known; the more awareness we have of the spectrum of our consciousness, the less unconscious we are of self-limiting concepts, beliefs, or fears and their reflexive conditioning of our responses to situations we encounter. It is an interactive process of widening perspective that views people “as active organizers of their experience…and psychological growth as the unself-conscious development of successively more complex principles for organizing experience” (Kegan 29).

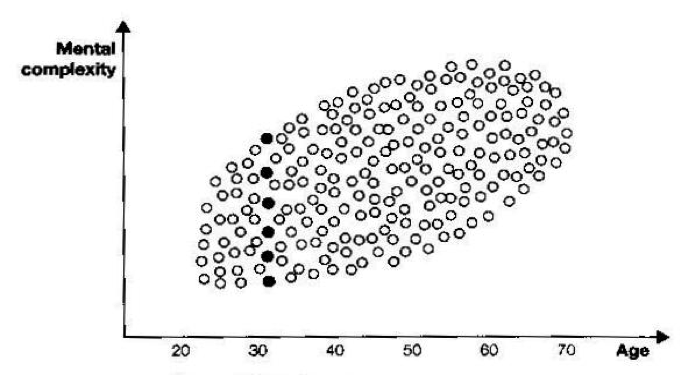

This process of mental development has only recently grown in acceptance among neurologists who had traditionally assumed that the brain did not undergo any significant change in capacity after late adolescence. “On the basis of thirty years of longitudinal research,” according to Kegan and Lahey, the data would show that “mental complexity tends to increase with age…[and] there is considerable variation within any age” (13-14). In Figure #1 from Kegan and Lahey’s research, “the upward sloping cluster indicates mental complexity increasing with age. The solid black dots illustrate different levels of mental complexity for six different individuals all close to 30 years of age” (13-14).

Figure #1 – Age and Mental Complexity: The Revised View Today

To be sure there is still great variety in mental capacity among individuals at any point in life, but the general trend is upward.

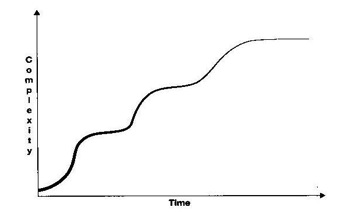

Illustrated below in Figure # 2 is the result of quantitative analysis of hundreds of transcripts of individuals interviewed and re-interviewed at several-year intervals by Kegan and Lahey and their colleagues. The graph demonstrates:

- Qualitatively different, discernibly distinct levels which are not arbitrary, but represent different ways of knowing the world,

- Development does not unfold continuously, but swings between periods of stability and periods of change,

- The intervals between transformations to new levels gets longer and longer

- There are fewer and fewer people at the higher plateaus (15)

Figure #2 – The Trajectory of Mental Development in Adulthood

The three plateaus or stages that emerge out of the data are indicative of different relationships between the knower and the known (call them worldviews), each with a logic that provides a framework for extracting meaning from life experiences. At the earlier end of the spectrum the focus is more about how others see us—to be perceived as competent, capable, and dependable—what Kegan and Lahey calls “socialized mind” (17). Here societal norms form the boundaries of self and determine what is important to pay attention to. At the latter end of the spectrum (the self-transforming mind), it is more about perspective building beyond the limits of an ego-based personality. Here a transpersonal objectivity gives rise to a multi-dimensional view of life that shapes the experience of self.

For the participants in my study, the influence of their transpersonal awareness is clearly evident. They struck me as modern day astronauts who metaphorically were sharing experiences of looking back on the world. On more than one occasion I was reminded of a sonnet Shakespeare wrote on the nature of love, which he describes as “the star to every wandering bark,/Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken” (116.7-8). Like ships upon the sea, the individuals I interviewed navigate their lives on the basis of a reality that lies beyond the physical limits of this world. Rather than orienting themselves in terms of identity and purpose on the expectations of others, generally or specifically, they find their location—their sense of place and direction—in relationship to the unfathomable depth and infinite dimensions of love.

Perspective

How they attempt to gather perspective as the focus of their meaning making efforts is illustrated in a brief flavor of the language they used:

“Obviously the beliefs I hold do matter, but at what layer of consciousness do I hold these beliefs? How did I come to be here in this reality? Obviously my ego didn’t choose this for myself. That belief must have been held at the Higher Self level for this reality to be in the first place and for me to be here.”

Participant C

“I do not hold other people responsible for my happiness or fulfillment. I find that focusing on anger usually gets me stuck, so I experience it and move on. My guidance continues to remind me not to take everything so seriously.”

Participant D

“I am much more aware of what is current around me, but it is like being in an open time book: touching past, present, future all at once. I can be present to others in this time and present to all time simultaneously. It is as if I am both a witness and a participant in the events around me. I can be in a doing mode and a meditative mode simultaneously.”

Participant K

“The me-ness that is inside is looking out of the eyes of my body. I have gotten most of my lessons through my body. Pain is no stranger to me. The way I can receive those messages now are very different. I once was very ambivalent about being here, in this body, but now I feel very complete.”

Participant Q

A number of implications follow from a self-orientation based on a transpersonal perspective. In this article I focus on four of the common characteristics I captured from the set of interviews:

1) Engagement of Multiple Intelligences—development of multiple forms of expression including music, art, and physical movement (dance, athletics, body work) to supplement abstract reasoning as a way of knowing.

2) Anticipation of Liminal States—being in transition on a more frequent basis and with an increased interest in the white space or the unformed dimension of possibility that exists between two or more existential planes.

3) Relationship with Inner Guidance—being present to an interior silence or transpersonal awareness while simultaneously interacting in the world.

4) Compassion for Oneself and Others—the essence behind the instinctual needs of human existence which shows up in a qualitative shift in regard to self and others

Engagement of Multiple Intelligences

What constitutes intelligence is often debated. However, its relative importance as an indicator of human distinctiveness is not. While definitions of intelligence vary, the root meaning of the word is “to understand,” which is directly related to our meaning-making capacity. In times of uncertainty, to revel in the question rather than possess an answer is to move from the known into the unknown with the realization, according to Werner Heisenberg, a Noble Prize physicist, that “we may have to learn at the same time a new meaning of the word understanding” (201). What Heisenberg came to realize in the course of developing a scientific principle based on relationships of uncertainty is that the wider one’s embrace of the objects of knowledge the more the results challenge our own underlying assumptions about reality. Such a paradox is particularly relevant to one of the dominant characteristics of the participants in the TMI study.

The search for meaning may be the driving force of human existence, but the passion or energy associated with this effort is not sufficient for transpersonal objectivity. There is a further quality needed that shows up among the participants as their most prominent reason for attending these programs—curiosity (Danielson, 2008). For those gifted with the irreverent quality of exploration for its own sake, questions are merely the means for taking the next step into the unknown. It is something they were nurtured in early through development of a rich imaginative life, which took root in many different activities:

“My best memories…lots of make believe. I played on a magic carpet that took my friends and me into new worlds where we had many adventures. I remember telling one my friends that he was so lucky because he could grow up to be an astronaut…But I was just curious about a number of things.”

Participant A

“I was really good at daydreaming. I liked to role play…Because of my father’s work [an historian who recreated live representations of American pioneer life], I lived in a fantasy world. Life was all about going out to have adventures.”

Participant B

“I was always active, always exploring. I played cowboys and Indians with the neighbors. I had a very active imagination…created places in our yard for building forts and pathways. I imagined the world of King Arthur and the intrigues that took place at court.”

Participant E

“I was often accused of having an overactive imagination. I had an imaginary friend for three years who was a very vivid presence in my life.”

Participant P

It could be argued that imagination is another sensory organ, a means for exploring beyond the limits of the known. Clearly for the participants in this study it was an active element in their lives. What is also clear is how the function of imagination, as the agent of curiosity, continued to evolve in the course of their lives. The development of multiple aptitudes or, to use Howard Gardner’s term, multiple intelligences, beyond the early interest in playing “make believe” is indicative of this evolution as Appendix 2 illustrates. While some of these interests proved to have an economic by-product at various times in their lives, the more instrumental goal they served was to widen the range and deepen the nature of their explorations. To refer to their interests and abilities as evidence of multiple intelligences makes this point. To be clear, I am not proclaiming a theoretical link between Gardner’s research and the aptitudes of the participants in this study. I am noting that the idea of understanding as a definition of intelligence is more than an ability to solve problems. There is a capacity for learning that has as its goal new vistas, new worlds, and wider perspective, even at the risk of undermining one’s current worldview. The development of multiple intelligences is more an expression of different ways of conducting that exploration. For self-transforming individuals, a journey of possibilities is more relevant than having a fixed destination.

Anticipation of Liminal States

Liminality is a description of the transitional phase between different existential planes. The definition can extend to a number of categories from ritual practices, to time (twilight or changes of season), to physical location (the edge of a forest or other points of spatial change), to identity (mixed ethnicity or transgender sexuality). Within ritualistic practices of modern culture a classic example is the state of being engaged. This is a liminal state for those who are neither single nor yet married. It is also a state whose boundaries have a powerful effect on others. In my own case, I remember the confusion and embarrassment I felt in college when attempting to ask a girl for a date only to learn she was recently engaged (sans ring because her fiancé was in another city and had not yet given it to her). My clumsy reaction, due to feeling I had committed a terrible taboo, was really quite amusing to her now that her search for the “right person” was seemingly resolved. The liminal state of engagement can result in a unique perspective on courtship (the past), which may have accounted for her reaction. At the same time, with their objective close at hand but not yet attained, the engaged have time to reflect on the marriage that is yet to occur (the future). Engagement is a period of new awareness resulting from an in-between state and it is this temporal boundedness which gives it a magical quality.

When describing the participants in this study as being well acquainted with liminal states, it applies not merely to the typical categories listed above but also to states of consciousness. In the use of the audio-guidance technology at TMI, exposure to the threshold between waking consciousness and the different focus levels associated with changes in brain wave activity is a liminal state whose frequency of experience is a differentiating aspect of their lives. The idea of expecting the unexpected, as previously noted, became a reason for returning to the institute. It is a frame of reference they become familiar with; the unbounded state between the past and the future, where something is going to change even though it isn’t entirely clear what. It is a moment of awareness between what has been and what can yet be, between who we think we are and what yet is possible. Finally, it is a point of demarcation that can be mere seconds in length or a no-man’s land where we can wander for years. While it is a disruptive time, it is not an unusual state, as Nietzsche’s observation attests:

Those thinkers in whom all stars move in cyclic orbits are not the most profound: whoever looks into himself as into vast space and carries galaxies in himself also know how irregular all galaxies are; they lead into the chaos and labyrinth of existence. (175)

Participants in this study have learned to consciously spend time in the white space known as the unformed potential or prima material of life. They actually seem to enjoy it as if it is part of a practice in the artistry of their own lives. They use phrases, illustrated below, that provide some insight into their attitudes toward change and transition:

“Watching my inner resistance.”

Participant B

“Stepping more fully into life (into possibility) rather than walking around the edges.”

Participant G

“Becoming unsettled is important to learning.”

Participant K

“From certainty, to uncertainty, to certainty is what defines me [a reference to a continual loop between polarities].”

Participant P

An experience shared by Participant C characterizes the liminal state taken to its transcendent conclusion. He was explaining what happened to him one day while he was driving:

“[Suddenly] everything just vanished and I am in an eternal moment as a point of consciousness that can see in all directions. There are lines of light going away from me; my possible and probable futures…And between every moment. Here, I am in a moment There, and I am holding different memories of the future and the past, every moment. It kind of reminded me of the white frames in between the movie pictures.”

When I asked him what was different for him now, he replied, “in a way nothing and in a way everything.”

To navigate one’s life unconsciously based on assumptions derived from past experience is like having a hammer and seeing every problem as a nail. It is a logical orientation only to the degree past experience is applicable to the present or current context. And current context is to a large degree a result of what we are capable of seeing or envisioning as Richard Tarnas notes:

Although there exists many defining structures in the world and in the mind that resist or compel human thought and activity in various ways, on a fundamental level the world tends to ratify, and open up according to, the character of the vision directed towards it. (406)

Such is the function of self-transforming individuals. They are more likely to question their existing assumptions in the light of what more there is to learn (or unlearn). They are more likely to suspend judgment rather than imbue it with a privileged status, which as Jung wrote, “is always based on experience, i.e., on what is already known [and] as a rule it is never based on what is new, what is still unknown, and what under certain conditions might considerably enrich [consciousness]” (CW 8: 136). In other words, the value of liminal states is the means for building greater capacity for openness to “what is still unknown.”

Relationship with Inner Guidance

When referencing transpersonal experiences, which participants in this study do in a variety of ways (often without using the term transpersonal), it begs the question of what is similar or different among their experiences. The idea of the transpersonal emerged in the last century among psychologists who view the ego-based personality and its centralizing function of consciousness within individuals as but one part of a totality defined as the Self. Within this totality is a spectrum of consciousness that is not limited to classic notions of physics (time-space continuum) or autonomy (I in relation to my thoughts). Boundary violation on either dimension (physical or mental) is often grounds to speak of a mystical experience. The variety of experiences cast as mystical has been well documented by Michael Murphy in his book The Future of the Body (the title alluding to the fact, in Murphy’s thesis, that what we call mystical is a form of meta-normal human functioning or human potential yet unrealized within a normal range of functioning). Robert Forman, in his book Mysticism, Mind, Consciousness, makes a further distinction regarding mystical experience by distinguishing between “intentional consciousness” and “awareness per se” (112, 131). The former is what we use in crafting our worldviews. It is indicative of our stage of development and, some would say, our reason for becoming human—to learn how to expand our consciousness. The latter is non-distinct from the object of its knowledge—knowledge of all things all at once. From where this awareness stems is no place and it is every place. It has many names and they are all symbols of the ineffable principle of existence—Yahweh, Tao, Atman, Godhead, “a being beyond being and a nothingness beyond being” (Eckhart 178).

Forman calls the two orientations and their epistemological structures “the dualistic mystical state” (150-151). In his definition, awareness per se is not a temporary state (a peak experience), but co-exists simultaneously with engagement in the world. It is the phenomenon of intentionally knowing (knowledge by direct sensory contact or through conceptualization) combined with non-intentional knowing. In other words, the dualistic mystical state knows the self reflectively simultaneous with seeing, acting, thinking, etc. The result is a permanent presence of awareness, which can be characterized as an unchanging silence within. The way that showed up for most of the participants in my study was through an ever-present sense of guidance.

“I always had a strong presence of guidance [which has been experienced as] a sense of grace most of my life. Rather than struggling with my choices, I have felt guided to go through the open doors the universe has provided me.”

Participant D

“I have experienced a place filled with love that is always there; a place I go back to whenever I want. It is a reassuring feeling I carry.”

Participant F

“I am now in a state of silence even in the midst of others. As emotions come up I can witness them.”

Participant K

“I am conscious of a quiet or a peace that is always present behind my ego.”

Participant M

The co-existence of an awareness that is clearly transpersonal in nature with the discerning qualities of our unique mental and emotional apparatus becomes a permanent fixture in their lives. What may have begun as a goal, “glimpses into the transpersonal waves of awareness,” is often transitory (Wilbur 269). The peak experience associated with awareness per se is a tool for learning and development, not an end in itself. For those whose forays into the transpersonal are temporary in duration it is but the beginning of a deeper transformation. To stop short of that work is the result of what Jorge Ferrer calls “spiritual narcissism,” which he describes as a failure to adequately integrate spiritual openings:

The structuring of spiritual phenomena as objects experienced by a subject [leads] to a conception of spiritual phenomena as transient experiential episodes that have a clear-cut beginning and end—in contrast, for example, to realizations or insights that, once learned, change the way one sees life and guides one’s future actions in the world. (38)

One of the distinguishing differences identified in the first phase of this study between those who had only attended one program and those who had attended multiple programs was not merely the nature of the shift in their personal worldviews but also the degree of self-awareness evident in their level of self-disclosure (Danielson, 2008). One reason for this difference is a lasting presence of an inner awareness or presence referred to as guidance.

The confidence with which the participants gave to this inner guidance was quite evident even while they told stories of decisions and actions they took that ran counter to familial, cultural, or societal norms. When I probed to understand the abiding value of what at times could appear to be a flippant reference to this invisible force in their lives, I was frequently surprised with what I heard. To give but one example:

“What have I learned from my guidance? How to awaken to the truth of who I am by recognizing the shame and guilt I still carry and to love myself as I am. I have carried an unknown wound throughout my life [she was sexually molested as a child]. I saw the effects of it but didn’t understand it.

“My first insight into healing was taking responsibility for my own feelings. My second insight was to discover that there is nothing in the terrorist that isn’t also in me. My third insight, the universe is a mystery. Let go of the idea of ever figuring it out, of putting the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together.”

Participant B

There is a paradox of control within their lives that is instrumental to their state of being. On the one hand, they are actively engaged in the world across multiple roles as they clearly detailed in each interview. They are parents, siblings, sons and daughters, spouses, lovers, bosses, workers, community volunteers, friends, and citizens. They are players in the game of life. On the other hand, there is an undercurrent to them that I became more attuned to in the course of each interview. What emerged was a deeper dimension of self; the ineffable principle of being they carried whose choiceless awareness instilled a distinctive energy. Call it the witness state, but their surrender to it is the guiding force of their lives.

Compassion for Oneself and Others

In spiritual traditions, it is not unusual to speak of compassion as a sign of enlightenment. William James, one of the early social scientists to investigate and categorize spiritual experience in terms of psychological functioning, reviewed the case files on hundreds of individuals to explore the relationship between mental health and spiritual vitality. In his seminal work delivered as a series of lectures that was later published as a book entitled The Varieties of Religious Experience, James determined that there are four “qualities of sanctification [that arise with] the attainment of a new level of spiritual vitality.” To briefly summarize they are:

- A feeling of being in a wider life than that of this world’s selfish little interests;

- A sense of the friendly continuity of the ideal power [Higher Self, Atman, Tao, God, etc.] with our own life, and a willing self-surrender to its control;

- An immense elation and freedom, as the outlines of the confining selfhood [ego] melt down; and

- A shifting of the emotional centre towards loving and harmonious affections, towards ‘yes, yes,’ and away from ‘no,’ where the claims of the non-ego are concerned (193-94)

While the participants in my study never described themselves as enlightened, many of the qualities James identified were evident in their lives. Further, there is a distinctive element to their lives in the notion of a “shifting of the emotional centre towards loving and harmonious affections,” what I am terming compassion, which first had as its objective the trauma of their own lives.

Behind the disclosures they shared with me was an awareness of the consequences of their trauma in terms of a loss of self-confidence, heightened anxiety, depression, alienation, and splintered egos. The straightforward way in which they spoke of their shortcomings and the inner work they had done and/or had yet to do demonstrated a degree of personal objectivity that is consistent with self-transforming individuals. But beyond that was the extraordinary level of care they felt they had received in their lives. They pointed to it in many ways from how they addressed their fears, to how they perceived their lives and their choices, to how they now interact with others:

“I came to realize I needed to find my own path towards wholeness. I could become an incredible thief or I could become a great person.”

Participant E

“All my life I have felt there was always something other than me that took care of me.”

Participant F

“The irresistible forces in my life seemed to condemn me to bouts of depression that left me struggling for understanding. When I had a heart attack, a light filled my existence with an experience of love that overwhelmed me for days. Since then I have felt a sense of acceptance.”

Participant I

“I began to forgive myself for some of the things I was still judging myself harshly. Essentially, I have learned to take responsibility for my life rather than getting stuck in the victim role of trying to please others.”

Participant J

The healing that occurred in their lives, resulting in a qualitatively different self-regard, is not a short-term experience. It had been underway for years, as most of them realized. The difference in their understanding was an acknowledgement that, as Participant M described, “I was always protected.”

As they learned to acknowledge the extraordinary care operating behind their individual circumstances, they acquired a similar regard for the suffering of others. It is an orientation based on an understanding that they are not the cause of any comfort that others experience, but rather, agents in “helping others take their next step.” When I heard this expressed in one of my interviews, the image that came to mind was of those who can appear in times of turmoil and distress to help us across the threshold of change and transformation. This work is vocational in the sense of “being called” to be present with others; what I understand William James to mean in his reference to “spiritual vitality” as the, “shifting of the emotional centre towards…’yes, yes,’ and away from ‘no,’ where the claims of the non-ego are concerned” (194). The following quotes illustrate the point:

“As a result of the energy that flows through me now, the one thing I care about more than anything else is the awakening of whoever I am with. It isn’t that I don’t have my own desires, but they are subordinate to this guidance.”

Participant B

“My purpose is to help show people a space of love that is already there for them.”

Participant D

“I know I am dying (shedding my skin), but I am hopeful I will have more time here, more opportunity to love. My work is to be a full-time student of life; my exchange is giving and getting love.”

Participant F

“My purpose, which is the covenant I made with myself before I was born, is sharing healing energy to help others through the trauma of the human experience.”

Participant O

The instinctual dimension of human nature exists to protect us and does so in the formation of filters or underlying assumptions which suppress fears associated with pain and suffering. Aspects of self that create a sense of risk or intolerable anxiety are split off and remain unrealized, fragmented, disintegrated. This is the wounded psychic state that the participants in my study experienced. And yet it wasn’t courage that led them out of their psychological wilderness. It was compassion. The essence of the human experience isn’t the conditioning acquired to protect or shield our woundedness. It is the experience of what Joseph Campbell called “invisible hands” that are guiding us “to discover our own depth.” The result is “[we] put ourselves on a track that was always there for us“and doors open where we didn’t know they were going to be” (The Power of Myth, 120).

Conclusion

The polarities behind the ambiguity of the global environment create conflicts that cannot be resolved by mere expedience. On the one hand, leaders are responsible to their stakeholders. On the other hand, there are the inspirational requirements of their own lives—responsibility to self-expression and inner guidance. The synthesis of these responsibilities is what wholeness requires. At the heart of any new paradigm is a tension between an emergent perspective and an established way of being. Integration is never easy, because the result is a reversal of a logic that could not have been possible before—a mystery “beyond human solution,” to quote John Henry Cardinal Newman (323). In Dostoevsky’s The Brother’s Karamazov, Mitya has lived in a completely self-absorbed manner when one day he falls asleep during a state of lethargy as a result of the purposelessness of his life and has an astounding dream. He witnesses the human suffering of his country that leaves him wanting to cry, but more importantly, feeling:

a tenderness such as he had never known before surging up in his heart…he wants to do something for them all so that the [baby] will no longer cry, so that the blackened, dried-up mother will not cry either…And his whole heart blazed up and turned towards some sort of light, and he wanted to live and live, to go on and on along some path, towards the new, beckoning light, and to hurry, hurry, right now, at once! (Dostoevsky 508)

As Colin Wilson notes, “to escape the prison of his own self-regard, [Mitya]…discovers that he is in a world that is so full of misery that his only business is to love” (189). Maybe this is the curriculum required for global leaders today—to learn how to create that third space for others to discover a purpose that lies beyond “their own self-regard.” The means for doing this work is a state of mental functioning I have labeled the self-transforming mind.

Appendix 1

Consciousness and Hemi-Sync

Ronald Russell

Hemi-Sync (Hemispheric Synchronization) is an audio technology developed by Robert Monroe. It is designed to produce in the listener whole-brain coherence; a state of consciousness defined when the EEG patterns of the two hemispheres of the brain are simultaneously equal in amplitude and frequency. It is based on two naturally occurring auditory phenomena: frequency following response and binaural beat stimulation. Listening closely to sounds of specific frequencies enables you to reproduce those frequencies in your own physiology. You can become entrained to the state of awareness engendered by those frequencies (for example, they can alert you, focus your attention, relax you or send you to sleep) and with practice you can learn to reproduce these states at will.

Binaural beats are produced when slightly different frequencies are introduced into each ear. The brain discerns this difference and seeks to bridge the gap, thus producing a third frequency – the difference between the two. These resulting frequencies are generally below detection by the ear and tend to stimulate the state of hemispheric synchronisation, a state in which the mind is awake and alert and may be guided into a sustained state of awareness while the body is totally relaxed. The process also involves verbal instruction, relaxation exercises and guided imagery, crafted together to engender desired states or phases of consciousness. It does not employ any subliminal suggestions.

Over the years the Hemi-Sync process has been developed and refined with the help and advice of scientists, engineers, physicians, educators and many other professionals. Studies and trials have taken place in several universities, hospitals and research organisations and trainers and presenters are active in some twenty countries around the world.

Robert Monroe maintained, “Focused consciousness contains definitive solutions to the questions of human experience.” The Hemi-Sync process enables those who use it to learn how to investigate those solutions and apply them to the matter in hand.

Hence it provides a readily available tool for those in leadership roles, clarifying the various issues and pointing the way to their outcomes.

Appendix 2

Representative Sample of Multiple Intelligences

Partial List of Participants

| Music/ Dance/Art/Film Production | Creation and Operation of Independently Owned Business | Writing/ Computer Programming | Acting/ Public Speaking/ Teaching | Athletics/ Outdoor Activities | |

| D | Self-trained painter. | Currently runs her own business as a physician. | Teaching part-time at the University level. | Biking and yoga. | |

| E | Opera Singer – performed at the MET in New York – and songwriter in her early career. | Started and currently runs a management consulting practice with her partner. | Author of short stories, poetry, and scholarly articles/books. | Teaching and public speaking as a consultant in the field of organization development. | Softball, basketball, track and field, and field hockey in school. Currently a stable of horses. |

| F | Started a manufacturing business and sold it. Currently runs his second business in manufacturing supply. | Studied acting in Paris after college. Worked in the theater in San Francisco and Boston. | Cooking, car repair, and general mechanics. Outward bound, cross-country running, and wrestling in school. Yoga as a young adult. Currently rides motorcycles, pilot’s sailboats, and has gone skydiving. | ||

| H | Plays the violin and guitar. Uses music in her education and therapeutic practice. | Formed and currently runs a therapeutic practice for children with feeding, swallowing, oral-motor, and pre-speech problems. | Author of scholarly articles/books. | Teaching and public speaking in continuing education programs. | Camping, hiking, climbing trees as a child. Rowing and hiking yet today. |

| I | Started and currently runs a translation business. | Astrological writing. Scholarly articles in transpersonal psychology. | Shakespearean trained actor. Taught English in Saudi Arabia. Former principal of a school in Australia. | Yoga | |

| L | Plays guitar, trained in music theory. Artist in the field of animation and film production (created a way to make 3D animation before the era of computers). | Started and ran IT consulting business. | Software programmer. | Yoga | |

| M | Drawing and illustration (works part-time as an illustrator for a museum of natural history). | Started and currently runs a horse training business. | Mentoring emotionally disturbed children. | 4H in high school. Professionally trained horse trainer with horses of her own. | |

| N | Musician certified in the Music for Healing and Transition Program. | Independent consultant in the field of technical project management. | Hospice volunteer. Certified professional coach. | Camping, hiking (was a boy scout). Private pilot license to fly small aircraft. | |

| O | Ballet and modern dance. | Started and sold a computer supplies company. Started and currently runs a business in health and wellness offering massage, exercise and diet classes, and meditation. Started and currently runs a staffing/ employment services business. | Gifted athlete. Performed in a number of fields including skating, swimming, sailing, gymnastics, and track and field. | ||

| Q | Professionally trained dancer. | Started and currently runs a physical therapy practice. Previously made her living as an author. | Writer of plays, short stories, and articles for magazines. | Spent her early career as a teacher (K-12). Also taught canoeing and rowing. Did further qualifications in theater and drama. | Canoeing, rowing, yoga. Feldenkrais practitioner. |

Works Cited

Campbell, Joseph. Interview by Bill Moyers. The Power of Myth. Ed. Betty Sue Flowers. New York: Broadway Books, 2001.

Danielson, Cam. Phase-One – The Effects of Long-Term Participation in The Monroe Institute Programs. Unpublished Manuscript, 2008.

– – – Phase-Two – The Effects of Long-Term Participation in The Monroe Institute Programs. Unpublished Manuscript, 2010.

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Eckhart, Meister. Breakthrough: Meister Eckhart’s Creation Spirituality in New Translation. Introduction and Commentary by Matthew Fox. New York: Image Books, 1980.

Ferrer, Jorge. Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001.

Gardner, Howard. Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang Von. Faust, Part Two. Trans. Philip Wayne. London: Penguin Books, 1959.

Heisenberg, Werner. Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science. New York: Harper & Row, 1958.

Horney, Karen. Neurosis and Human Growth: The Struggle Towards Self-Realization. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1950.

James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Jung, Carl Gustav. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Trans. R. F. C. Hull.Vol. 8. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

Kegan, Robert. In Over our Heads: the Mental Demands of Modern Life. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Laskow Lahey. Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2009.

Murphy, Michael. The Future of the Body: Explorations Into the Further Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam Books, 1992.

Newman, John Henry Cardinal. Apologia Pro Vita Sua & Six Sermons. Ed. Frank M. Turner. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Nietzsche, Frederick. Basic Writings of Nietzsche. Trans. & Ed. Walter Kaufmann. New York: The Modern Library, 1992.

Pirsig, Robert. Lila: An Inquiry into Morals. New York: Bantam Books, 1991.

Shakespeare, William. The Complete Works. Ed. G.B. Harrison. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1968.

Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas that have Shaped Our World. New York: Harmony Books, 1991.

Wilber, Ken. The Eye of Spirit: An Integral Vision for a World Gone Slightly Mad. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1997.

Wilson, Colin. The Outsider. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1982.

About the Author

Camden C. Danielson is a partner at MESA Research Group. His work focuses on assisting leaders and management teams revision future direction and opportunity amid the turbulence of personal, organizational, and societal change. His research has appeared in The Monroe Institute Journal, Academy of Management Executive, Human Resource Development Quarterly, Business Horizons, and The American Benedictine Review. Cam’s background includes 20 years leading the office of executive education at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. He also was a speechwriter for the President of Indiana University and a member of the faculty at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Cam received a B.A. in Classical Studies from the University of Kansas, a Medieval Studies Certificate and an M.A. in English Literature from Indiana University. He participated in the American Center for International Leadership US-USSR Exchange Program (1985) and is a graduate of the U.S Air Force Squadron Officer School (1981).

Pingback: March 2011 Table of Contents

Pingback: Feature Articles