Mark L. McCaslin and Karen Wilson Scott

Great spirits have always found violent opposition from mediocrities. The latter cannot understand it when a man does not thoughtlessly submit to hereditary prejudices but honestly and courageously uses his intelligence.

~Albert Einstein

As we observe the mantle of instructor flow from student to student in an open pattern governed solely by the will of the members of this learning community, my colleague and co-potentiator provides this synergistic group with another question that deepens their discussion: “Recognizing what resonates with your philosophy of teaching and learning, what unsettles it, or perhaps, ignites it to explore new possibilities?” More waves of discussions ensue. The assignment was to reflect on what and who informs their philosophies of teaching and learning, and how those philosophies have and will evolve. Stimulating learning through thoughtful/thought-provoking inquiry, potentiating contributions as well as participation—an intervention of the highest sort—a purposeful interdependent activity serving to catalyze principled response and responsibility is what we call catalytic teaching; it is the enlivening force of metagogy.

While more will be revealed concerning the nature of metagogy, it is abstractly positioned as the teaching to and learning from human potential. It would be fair to ask at this point, “What does teaching and learning have to do with leading and leadership?” In particular, the connection of teaching and learning to Integral Leadership and Second Tier Leadership might seem opaque. To clarify this connection we would position metagogy as an integral educational force that would complement the evolving nature of leadership studies and therefore leading at and from the Second Tier. Metagogical teaching and learning adds considerable reach to Second Tier Leadership in terms of its designed aim of revealing and actualizing unrealized potentials within the learning dynamic. This approach to teaching and learning serves as a bridging dynamism as the potentiator locates, catalyzes, and then seeks to actualize all potentials within a given Eco to include their own. Metagogy fits well in the Integral Leadership tool bag.

The Potentiator

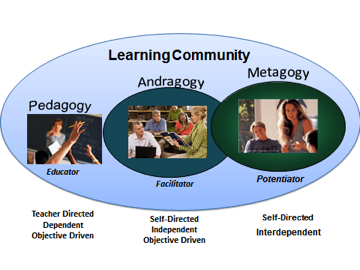

Introduced above is an orientation and approach to learning—metagogy, a practice or activity held by that approach, catalytic teaching, and a way of being for the teacher that we now refer to as the Potentiator. The Potentiator reflects Second Tier qualities and actions that differentiate them from other instructional roles as is shown in Figure 1.

The practice of catalytic teaching presents an opportunity to evolve a new approach to teaching and learning that engages and potentiates the farther reaches of a community of learning. This is, in effect, Second Tier Teaching and Learning. It is this catalyzing stance that can reveal the essence of what it means to be a Potentiator. In observing the qualities we have seen and felt it became clear to us that these Potentiators are first self-aware. We came to understand that they are able to hold space for acts of potentiation for themselves and others by way of an opening awareness, a welcoming acceptance, an ability to sustain attention and through setting their intentions on the full actualization of human potential. These are critical qualities for Integral Leadership.

Potentiators are forever open to learning. As they engage the relationship they ask, “What have you come to teach me?” They are expert listeners, not solely because of discipline and practice, but also due to a deep seated curiosity so present in a life of potential. Potentiators are able to suspend the vector and velocityof their daily activities and thoughts. This means they act on the urgency of the moment—the urgency does not act on them. Their integrity is contagious. They are mindful of their interactions as they understand the nature of human evolution—potentiators understand that we are all self-evolving. They understand that when something evolves everything around it evolves as well. Potentiators adapt themselves to the world and are able to accommodate the evolving gifts of others. They maintain an elegant prejudice. Their super optimism and vision for the full actualization of potential grants them a peace that stems from a belief in the infinite potential for goodness held by the human ecology. (McCaslin &Snow, 2010)

Potentiators, as Maslow (1968) would say, approach life with a “second naiveté” or hold the world with an “innocent eye”. They understand as did Socrates that “wisdom begins with wonder” (Hamilton, 1943, p. 100).

Catalytic Teaching

Catalytic teaching is a form of instruction practiced by potentiators that inspires creativity and higher levels of intrinsic motivation commonly found at the Second Tier. Catalytic teaching is essentially an opportunity for potentiators to develop, rethink and improve imaginative, innovative and artistic aspects of their teaching and learning by means of a creative multiple-concept segment of instruction or training aimed solely at deepening and provoking the potentiator and learners to reach their own and their learning community’s fullest potential. This can have broadening implications for integral leaders, coaches and trainers in terms of their abilities to sustain and build the capacity of people and organizations.

Catalytic teaching advances higher and deeper understanding of a concept. Once that new understanding is attained, the learners’ perspectives are broadened, clarified. At the same time they critically reflect on their learning to more fully understand their own capability and to share their transformations with others to expand the potential of the learning community. This synergy is an essential relationship of metagogical teaching and learning. Catalytic teaching is aimed not at a particular objective, but rather at a community of individuals with their multiple ecologies and therefore multiple “right” objectives, approaches and responses. At the core of catalytic teaching is the belief that creativity and the act of creating are sacred to the human condition, that spirituality is a birthright that holds the soulfulness of possibility shaped by our innate need to create and to be creative and that empowerment is a growing inward force of creativity dedicated to the full actualization and expression of human potential.

Current and historical models of teaching, while well-researched and well-intended, too often leave the teacher with a haunted wanting (Brookfield, 1995, 2000) and treat the student as a product to be consumed (Pratt, 1998), rather than a potential to be actualized. Creativity is too often not celebrated in such efforts; rather out of fear, it is discouraged (Amabile, 1988). Human potential suffers as creativity is dismissed or is threatened by the ruthless metrics of failure. To effectively engage a Second Tier perspective is to follow what Cook-Sather (2002) calls a “change in mindset [that] authorizes student perspectives” (p. 3) in the potentiating and learning partnership. Learner-centered and integrally based attitudes and environments can effectively provide space for the creative way of being for both potentiator and learner, and in the process nurture the growth of human potential within the individual and the community of learning (Weimer, 2002). As a result, creativity coupled with an innate spirituality and a sense of empowerment form an inseparable triad that is foundational to catalytic teaching and therefore to the purposes of metagogy. Collectively this triad forms and represents the enlivening force of metagogy.

Metagogy speaks directly to the nature of creativity, intuition, imagination, play—to a spirituality uncommon in today’s learning places and organizations. Due mostly to our Western cultural heritage, evoking the notion of spirituality as a construct directly relevant to the nature of Second Tier teaching and learning can become for some a stumbling block (Tisdell, 2003). Yet metagogy, the teaching to creativity and potential, at its core is spiritual—is integral. Therefore, efforts here will be to transform spirituality into a stepping stone. We will suggest, and not in a derogatory sense, that it is our First Tier prejudices concerning spirituality that get in the way of understanding it in a deeper and more inclusive and universal way (Tisdell, 2003). Too often spirituality and religion are viewed as inseparable. However, we must agree with James Moffett (1994), author of The Universal Schoolhouse, that while spirituality may well be what all religions have in common, spirituality is not dependent upon or bound by religion. Tisdell (2003) suggests there is no way to avoid concepts like soul, heart, intuition, instincts, a calling, or spirituality when discussing the full actualization of human potential. They simply emerge like they were part of the landscape of our natural teaching and learning ecology. What we find to be true for others and ourselves is that efforts to fully actualize one’s greatest potential seem to be accompanied by or spring from spiritual experiences.

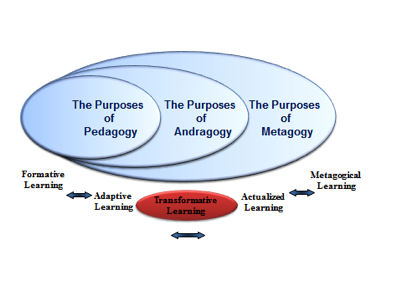

Metagogy is not intuitive for all. For example, early on in one course some students complained that catalytic teaching is “too open, too free.” These were graduate students in an adult education program. The course of study they were participating in was designed specifically for developing greater understandings of the nature of teaching and learning in community and higher education. They grappled with many open-ended questions and problems in other aspects of their lives. Why was it difficult to address open-ended instruction? The answers may lie partially in our common educational background and the paradigm we associate with education and partially from individual growth processes and dynamics. It is possible and desirable to design teaching environments to foster creativity in learning by emphasizing Second Tier motivations such as functionality, competence, flexibility and spontaneity (Beck & Cowan, 2006) that enhance the intrinsic rewards of the creative, synergistic teaching and learning process. As efforts increase in providing opportunities that inspire and encourage growth in a nurturing and potentiating environment, reciprocal teaching and learning occurs within the learning community. Each person in the community participates in creating that environment. Building a metagogical learning community means appreciating the diverse gifts of each individual as well as where they currently reside within the Synergistic Learning Continuum shown in Figure 2. As adult educators and potentiators, our philosophy is to create a fertile learning ecology that facilitates the relevant personal development of each individual, while simultaneously enriching an interdependent learning community no matter where the learner might be in their own development.

Metagogy

Pedagogy emerges from the Greek word ‘paid’, meaning child, and from ‘agogus’ meaning leader of (Webb, Metha, & Jordan, 1992). From leader of children we discern the modern meaning of the art and science of educating children (Knowles, Horton, & Swanson, 1998). While there are many examples of the use of pedagogical models with adults (Webb, Metha, & Jordan, 1992), the term more commonly used to address teaching and learning with adults is andragogy (Knowles, 1998). Andragogy, following the same logic, was originally defined as leader of men or, as is more commonly accepted, teacher of adults (Knowles, 1973). Based on the sets of philosophies that inform them, we believe that these two philosophical models are less about age and more about the teacher-learner and learner-learner relationships. For instance, pedagogy encompasses a wide range of educational philosophies ranging from a highly dependent mode that is rigidly teacher-directed (informed by perennial and essential philosophies) to a relatively independent mode that is flexibly teacher-guided and learner-self-directed (informed by progressive, existential, and reconstructive philosophies) (Webb, Metha, & Jordan, 1992.

Though Knowles (1973) differentiates andragogy from pedagogy through five assumptions concerning the separate educational needs and learning approaches of adults (Knowles, Horton, & Swanson, 2005), the practice of andragogy advocates the independent mode of teacher-guidance and learner self-direction that tends to resemble the more open, flexible positions of pedagogy. As pedagogical teaching and learning appears to speak to the entire spectrum of outcomes-based education, andragogy may be in fact an age-specific model within pedagogy. In both paradigms the teacher provides some level of direction toward a specific objective, whether it is a single objective, teacher-determined and dependently delivered, or whether parallel objectives are student-determined/teacher-guided and independently pursued by students (Shapiro & Levine, 1999; Weimer, 2002).

While our focus is on the relationship between the teacher and the learner, we do not want to casually dismiss the relevance of adult experience and life-centered pursuits that clearly differentiate adult learning from child learning. However, even with this distinction the cross over between pedagogy and its andragogical comparative is easy to construct. Knowles (1980) recognized that crossover in his later years, describing the construct in terms of a learning evolution from pedagogy to andragogy.

Neither pedagogy nor andragogy nor the bridging of one to the other appear to address an interdependent model of education where objectives are catalyzed by the teacher and interdependently developed and pursued by a community of learners to the mutual benefit of the self individually and the community collectively. The independent learner who seeks to be engaged in the advancement of his or her community would seek that interdependent frame we call metagogy. Metagogy is taken from the word ‘meta’ meaning ‘beyond’ or ‘through’ (Epstein, 1999). With the same logic previously applied, metagogy literally means beyond the leader or beyond the teacher. This paper explores the nature of metagogy as a Second Tier construct that will enhance the effectiveness of integral leadership by way of improving its ability to reach and potentiate individuals within the learning dynamic.

A Reasoned Approach

One can not, I say, attain supreme knowledge all at once; only by gradual training, a gradual action, a gradual unfolding, does one attain perfect knowledge. In what manner? A man comes, moved by confidence; having come, he joins; having joined, he listens; listening, he receives the doctrine; having received the doctrine, he remembers it; he examines the sense of things remembered; from examining the sense, the things are approved of; having approved, desire is born; he ponders; pondering, he eagerly trains himself, he mentally realizes the highest truth itself and, penetrating it by means of wisdom, he sees.

– Majjhima Nikaya, LXX

Inquiry and curiosity, research and imagination, study and creativity, exploration and play, and perhaps other odd couplings surrounding the ways and means of wisdom, offer ample room for understanding and participating in the authentic goodness of living, the nature of reality, the ontological and, following these, an integral Second Tier approach to teaching and learning. If we remove the conjunction, the relationship, the “and”, then we too often find ourselves in a time and place where our ability to engage and foster the deliberate alchemy of potential becomes shallow, lost or forgotten. In today’s learning ecologies we would seem unable to step over into the Second Tier given this loss of connection and the loss of a potentiating relationship. As a direct result our teaching and learning processes have found it a necessity of terrible consequence to separate these relating concepts into only truth and knowledge (the epistemological) or only beauty and creative pursuits (the axiological). Therefore, we break the relationship whereupon we find only inquiry, research, study and exploration that attempt to objectify all phenomena of potential into fact and theory. Conversely, taking the other course, we likely find ourselves alone with our purposeless curiosity, creativity, imagination and play, It is purposeless in its ways, because beauty, ethics, aesthetics must bow to the potency of truth and knowledge. The truth of our times seems only capable of an objectified beauty. There must exist a reasoned approach to education that does not require this separation, but instead seeks to hold the bonds that exist between us— to join together in the alchemical and Second Tier process of leading and actualizing human potentials. Perhaps what we seek, what we need, is a potentiating form of education. Metagogy offers such a fresh perspective and approach. It is an integral and Second Tier approach to the learning community.

The Nature of Metagogy

In pedagogy and in andragogy the objectives are predetermined, whether teacher-directed or teacher-guided and learner-self-directed. The goal of each educational paradigm is to deductively determine learning objectives and to structure curriculum toward their achievement. Metagogy begins with different assumptions:

- The usual state of teaching, therefore learning, is suboptimal, less than interdependent and therefore disconnected from the typical learner. Where the focus of educational programs and largely educational practice is currently on the content (i.e., teaching to an objective), it could rightly, some suggest should (Shapiro & Levine, 1999; Weimer, 2002), be on the learner (i.e., teaching to a person with his or her own objectives). This state, which we suggest is more optimal for both learner and teacher, occurs naturally at the intersection of potentials—those of the learner and those of the teacher (the potentiator).

- Where teaching and therefore learning may be suboptimal, this state can be resolved and advanced to optimal via methods that catalyze personal potentials for both teaching and learning.

- Awareness and reflection lead to sensitivity for the human potentials (Mezirow, 1996) before us, leading towards perhaps the greatest skill required by the potentiator—the ability to learn from and about the very ecologies of the learner (Scott, 2004). In truth, education does not rest beyond that point, but within it.

- Intentions move away from objective-based education and toward potentiated, mutual growth of the student, the teacher and the community.

Metagogy seeks to inductively catalyze open-ended inquiry in a community of learners in such a way that the synergistic flow of learning inductively discovers and provokes the questions appropriate to reach correspondingly appropriate truths for each community member and thereby for the community as a whole. Catalytic teaching (metagogical inquiry) potentiates “ah-ha!” understandings, stimulating the learner to make a quantum leap (borrowing a term from physics), a stepping straight up (as in from the ground to the top of a picnic table) in moving to a more holistic understanding of a new concept. Once that new understanding is attained, the learners’ perspectives are broadened, clarified, fitting more of the puzzle pieces together. At the same time they become metamotivated to intrinsically reflect on their learnings to more fully understand their own potential and to extrinsically share their transformations with others to expand the potential of the collective motivated by homonomy (Boucouvalas, 1988), connected self-directed/community-motivated selves (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartiner, 2007). This is neither a push nor pull, a lift nor carry, but an essential relationship of metagogical teaching and learning.

Psychologists tend to agree that relative to a needs hierarchy, people satisfy survival needs and belonging or community needs before reaching toward what Maslow (1971) refers to as growth needs. Maslow suggests that, as people mature, they seek and reach autonomy on several levels, the highest of which include Maslow’s self-actualization and transcendence (Maslow, 1971), Loevinger (1976) suggests people can advance to interdependent and integrated appreciation for other’s needs and views (Carver & Scheier, 1996); Kolberg (1969) claims a spectrum of advancement along a universal ethical principle orientation, Rogers (1961) describes a fully-functioning person and Csikszentmihalyi (1991) describes people reaching a state of flow. Notice that these high functioning states allow for developing one’s potential and having great appreciation for multiple views within a community, while maintaining one’s own view free of any defensive posture.

Buscaglia (1978) suggests that realizing maturational potentials are entirely possible within the individual. Metagogy recognizes that reach and seeks not to “push,” “pull” or “lift” the individual, but rather to potentiate him or her to find the personal inspiration within to reach higher toward his or her own Eudaimonistic goals (Norton, 1977; Ryff & Singer, 2008) for uniquely personal reasons.

Elements of Metagogy

The base elements of metagogy would include:

- Pure pleasure of learning for its own sake;

- “Pull” of commitment to learning through personal inspiration and intrinsic passion;

- Betterment of community not a goal, but a natural by-product of seeking highest potentials of members in an interconnected manner;

- Developing one’s potential, interdependently catalyzing and catalyzed by the learning community, thereby contributing to developing community potential;

- A requisite towards ethical teaching (view ethics not in terms of conventional morality but rather as an essential principle for teaching and learning);

- Embraces Maslow’s (1971) metamotivational values;

- Acknowledges learning as a dynamic and synergistic relationship contributing to the creation of opportunities used to address personal destinies within community;

- Inspires the cultivation of wisdom “whereas knowledge is something we have, wisdom is something we become. Developing it requires self-transformation” (Walsh & Vaughn, 1993, p. 51).These elements, when applied to the learning community, open the doors to a metagogical approach to teaching and learning.

These elements would locate metagogy as an effective approach to teaching and learning from the Second Tier.

Metagogical Teaching and Learning

Metagogical teaching and learning is an essential component for developing the learning community. In fact, it could be argued that without metagogical teaching and learning a true learning community might have less likelihood of reaching its full potential. Given that a learning community is enhanced by the growth of the individual, mutually encouraged collective individuation then provide fertile ground for metagogical teaching and learning to flourish. While it may be both impossible and undesirable to eliminate extrinsic motivators altogether (Ryan and Deci, 2000), it is possible to design teaching and learning environments to foster and nurture creativity by reducing the focus on extrinsic motivators and emphasizing intrinsic rewards of the creative synergistic teaching and learning process itself (Amabile, 1988; Halpern, 1996). If opportunities are provided that inspire and encourage growth and development that spring from metagogical teaching and learning as a Second Tier (metamotivational) value, it then becomes possible to reconstruct or redirect the forces working upon the human potential of our learning community. The Second Tier values work in harmony to create continuing opportunities to inspire the individual and larger community to individually/collectively step up to higher levels of expectations and possibilities. Moving beyond current levels of community understanding and expectations is the promise of metagogical teaching and learning. It illuminates a synergistic and vibrant teaching and learning relationship. The dynamic may well describe the true meaning of metagogy and the catalytic actualization of human potential. These growth and potentiating forces give rise to the teaching and learning approach that is metagogy. Therefore, metagogy is the art and science of interdependent growth through teaching and learning motivating and motivated by the creativity, spirituality and empowerment of the individual and the community.

Full appreciation of the nature of metagogical teaching and learning requires a fresh perspective and approach. A course on the psychology of learning would likely discuss learning as the acquisition of associations that are extrinsic rather than intrinsic to learner, currently often centering on self-determination theory (e.g., Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Deci, 2006). “Most of this [the psychology of learning] would be beside the point—that is, beside the humanistic point” (Maslow, 1971, p. 162). We believe Maslow was implying that learning does not rest fully within the cognitive domain. The development of a fully functional, fully human, self-actualized person must encompass skills and attributes included within the affective domain (Maslow, 1954; Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004) as well as thoughtful demonstrations and examples of being springing from the Second Tier. In reality, the most exhilarating moments in teaching and learning mostly reside at the cognitive/affective intersection (Halpern, 2003), which are then greatly enhanced by Second Tier metagogical designs and approaches. Gronlund (1995) concurs that “as behaviors move from simple to complex… they become increasingly internalized and integrated with other behaviors [to include the affective, cognitive and integral] to form complex value systems and behavior patterns” (p. 57). While some of Maslow’s metaneeds may arguably reside in the cognitive domain, it is clear that all of them belong to the affective and metamotivational domain.

In 1968 and again in 1971, Maslow made an alarmingly accurate prediction that he said, claimed we would see become truer each year. Maslow further suggested that much that we have called learning has become useless. “Any kind of learning which is the simple application of the past to the present, or the use of past techniques in the present situation has become obsolete in many areas of life. Education can no longer be considered essentially or only a learning process; it is now also a character training, a person-training process”. (1971, pp. 94-95)

Teaching and learning from this tightly-interwoven affective/cognitive/integral intersection—this Second Tier perspective—has a distinctiveness surrounding its nature. Higher order values, concepts and conditions of being human represent it. Teaching and learning as a spiritually higher order value presents ethical, compassionate and purposeful, inspiring hope, creativity, wisdom and empowerment to nurture unmet human potential. In searching for the farther reaches of human nature, Maslow (1971) stated the following tenet, “On the whole… I think it is fair to say that human history is a record of the ways in which human nature has been sold short. The highest possibilities of human nature have practically always been underestimated”. This tenet holds for teaching and learning, as well. In too many instances in today’s educational enterprises, teaching and learning have been demoted from their true nature and potential.

Research and theory in adult learning to large extent assumes that the mind and body are split, thus leading to an emphasis on cognition…. Embedded in this focus are the cultural values of privileging the individual learner over the collective and promoting autonomy and independence of thought and action over the community and interdependence (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2007, pp. 217-218, emphasis in the original).

Returning this enterprise to a higher order value and incorporating the affective and psychomotor domains (including spiritual and embodied learning) will ultimately lead to rediscovering the joy, creativity and spiritually (the metamotives) of teaching and learning.

Metamotives of Teaching and Learning

There is a relationship between teaching and learning. Vygotsky (1978) speaks to the relationship as found in the Russian concept of obuchenie, an interactive nexus between teaching and learning allowing for teacher and learner to take up both roles (Scrimsher & Tudge, 2003). In its ideal form this relationship would be represented by the metaneeds or metamotive values of what must be beautiful, good, perfect, just, simple, orderly, lawful, alive, comprehensive, unitary, dichotomy-transcending, effortless and amusing (Maslow, 1971). In describing the theory of metamotivation, Maslow (1971) claims that self-actualizing individuals who have gratified their basic needs “are now motivated in other higher ways, to be called ‘metamotivations’” (p. 289). Maslow’s use of the prefix “meta” was beyond the traditional postitivist meaning of “after” or “with”. His usage took on a much more spiritual meaning of “beyond” or “through” (a way of becoming), more transcendental in its reference. “Motivated in higher ways” suggests a desire to move beyond current levels of expectation and beyond our bias and even our fear. In an effort to find answers to what he referred to as the “Jonah Complex,” Maslow (1971) wrote:

We fear our highest possibilities (as well as our lowest ones). We are generally afraid to become that which we can glimpse in our most perfect moments, under the most perfect conditions, under conditions of greatest courage. We enjoy and even thrill to the godlike possibilities we see in ourselves in such peak moments. And yet we simultaneously shiver with weaknesses, awe, and fear before these same possibilities. (p. 34)

The relationship between teaching and learning, as we know it today, teeters on this fulcrum (Brookfield, 1986). Could it be true that this relationship, this bridge linking teaching and learning, coexists on the path to our greatest potentialities for creativity, our metaneeds? Can this relationship master our fears of reaching for our highest possibilities? Czikszentmihalyi (1988) suggests that optimal creative experience, which he terms “flow,” immerses a person so much in the experience that experience and person seem to become one. We suggest that the relationship bridging teaching and learning within a nurturing community of learners exemplifies flow, transcending concern for learning to a state of joy in learning. How can we find this path to our greatest potentialities? How can we bridge this teaching and learning chasm?

Community of Teaching and Learning

Having established the relationship of mutual teaching and learning as a metamotivational Second Tier function, which we refer to as metagogical teaching and learning, it becomes critical to reconnect the individual within the relationship. It is important to examine what elements draw an individual to the relationship in the first place. If we can effectively remove the specter of negative deficiency functioning relationships, e.g., the effects of deception, manipulation, coercion and intimidation, then we open the universe to the more positive aspects of the growing personality or individual. This positive individuation is often in motion within metagogical teaching and learning. We suggest that individuation through metagogical teaching and learning as a metamotivational value enhances the opportunities to actualize human potentialities with and within a community. Because through individuation learning is no longer defined as learning as a mere product of the concept of teaching, learning expands to encompass many attributes that on the surface may seem conflicting. Metagogical teaching and learning can be self-serving, community-serving and altruistic in nature simultaneously. Individuals within this dynamic can be both comforted and motivated due to the way in which metagogical teaching and learning advances their own growth and development without impinging upon the growth and development of others. The dynamic develops as a collective individuation, or homonomy (Boucouvalas, 1988), that may well define the nature of metagogical teaching and learning.

Implications of Metagogy to Teaching and Learning

It becomes critical at this point to outline the implications of metagogy, underpinned by the theory of metamotivation, on teaching and learning. Within this model the learner would move from the dehumanizing objectives-based orientation (dependence or independence of pedagogy and/or andragogy models) to the holistic person-within-a-community-based orientation (interdependence of metagogy). The latter recognizes and values individual and community objectives without the need to determine them.

As instructors, our metagogical teaching philosophy is that within a learning community all people have value waiting on its full expression. It would follow, then, that within this teaching and learning community each of us has something to teach and many opportunities to learn. We believe that this reciprocal teaching and learning can happen only if each of us feels safe in contributing to the discussions and activities of the community of learning. Creating such a safe and stimulating learning environment cannot be our (potentiators’) task alone; it is the responsibility of the entire community (Shipiro & Levine, 1999; Weimer, 2002) to protect and celebrate each contribution by our fellow members. Further, a community of learning thrives when each of our members is welcomed and encouraged (Shipiro & Levine, 1999). A sense of belonging is essential to the health of our community and for our personal growth and development (Beck & Malley, 2003; Brookfield, 1986; Glasser, 1986). Toward this endeavor, we ask only that we individually and collectively appreciate our gifts differing. By following these simple, yet elegant principles, we will find ourselves full circle—all people have value. Valuing one another is the first step towards metagogical teaching and learning.

Metagological instructors seek to create, facilitate and potentiate a learning environment that fosters the integrated intellectual, personal, social and ethical development of each individual as a community is nurtured. Each person in the community is integral to the creation of that environment by encouraging intellectual honesty and respectful listening to the views of others. As each person shares experiential and academic knowledge in this teaching and learning community, the goal is not to reach consensus, but to recognize underlying positive intentions and to value diverse ideas. The resulting interdependent collective of autonomous, self-directed individuals within this homonomous community (Boucouvalas, 1988), purposefully explore peak experiences (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991) and personal potential in a Eudaimonic (Norton, 1977) enterprise. This interdependent collaborative metagogical community catalyzes their own teaching and learning in a self-perpetuating process.

Beginnings

The essential aspects of the relationship that is metagogical teaching and learning seem to be seldom employed. We simply cannot know or appreciate the full weight of the power that this lack has on the learning community. Given that so many projects, actions or activities surrounding existing educational paradigms miss their mark or never quite leverage their full potential, it would seem wise to examine the nature of relationship described by metagogical teaching and learning. Hennessey and Amabile (1988) have studied environmental and social factors that both promote and encourage creative self-expression or undermine and discourage it. They concluded that the typical school and work environments not only are not conducive to the development of creativity, but they have in place many components that act to discourage it. Creative individuals are highly curious and their intrinsic motivation to follow their passion requires an open, supportive environment. Six conditions Hennessey and Amabile found tend to suffocate intrinsic motivation are constant evaluation, surveillance, reward, competition, restricted choice and extrinsic orientation toward an endeavor. All six suffocating conditions are to a lesser or greater extent aspects of the four heavies of the teaching/learning dynamic: manipulation, deception, intimidation and coercion.

That metagogical teaching and learning is antonymous with these behaviors is indicative of its importance to corrective action. Metagogical teaching and learning as a metamotivational value forges the unified commonality of purpose, creativity, connecting it with individual growth and development. What remains distal and yet strains to be proximal is the nature of metagogical teaching and learning springing from the Second Tier. The true essence of metagogical teaching and learning does not rest within the teacher or within the learner. The true nature of the relationship that is metagogical teaching and learning rests within the conjunction “and” (Wheatley, 1992). By understanding and improving what goes on among those in the teaching/learning relationship and by fostering a Second Tier approach, individuals, both teachers and students, will move forward in their own growth and development. As a product of this investment, the learning community is advanced by effectively creating opportunities for a synergistic society to emerge (Maslow, 1965, 1974). This learning community is no longer driven by transactional motives and short-term gain but by metagogical motives and long-term vision and commitment. This is in essence the nature of the dynamic and synergistic relationship that is metagogy.

Elevating metagogical teaching and learning to a metamotivational Second Tier value gives the learning community, as well as the individuals within them, the hope, the catalyst and the ability to maximize their potential. Unrealized human potential is perhaps the greatest single tragedy obstructing the growth of our species today. Given that most of the difficulty surrounding our growth potential exists in the relationships that surround us, then metagogical teaching and learning can be a powerful force in easing or removing obstructions to that growth. The changes effected by metagogical teaching and depend on how those relationships are experienced.

The landscape of metagogical teaching and learning is inhabited with purpose, creativity, spirituality and relationships. This article sought to illuminate the metamotivational aspects of this landscape. In 1990, John Gardner stated the following: “Is it not a shame that so many men and women, of extraordinary talent, die with all their music still within them” (p. 182). The promise of metagogical teaching and learning is the promise of expressed human potential.

Prologue

Each new birth is the birth of a new idea, a new possibility that has as its purpose the promise of a new and wonderful discovery. It has at its core the design of a purposeful life. We would wonder what or whom we will discover today? Robert Frost once said, “Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, ‘grace’ metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have. Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another” (Frost & Richardson, 2007, p. 104). Creativity is like that. Spirituality involves that. Empowerment realizes that. Metagogy presents us with the grand hope of creativity and the opportunity to nurture one’s daimon, one’s unique potentiality (Norton, 1977,) on a path of interdependently valuing individual and collective worth. Paraphrasing Robert Frost, to follow this way “has made all the difference” (Parini, 2000, 154).

Beyond teaching as we have come to know it we find philosophy—the love of wisdom. And we find philomathy—the love of learning. We believe this is the key—it imbues a deep respect, a deeper purpose, and it reveals the deepest layers of our potential. A beauty found can lead to a goodness shared with the ever present potential of movement toward a grand truth. This must be the true meaning of elegance for as Christian Lacroix states, “For me, elegance is not to pass unnoticed but to get to the very soul of what one is” (Breathnach, p. 107).

As we begin this journey towards a metagogical approach to education, this new tool for second tier leading and leadership, we find ourselves armed only with the hope that we can, in our teaching lives, become students of potential and “get to the very soul of what one is” (Breathnach, p. 107). And here “we,” all of us in relationship, will find, as always, potential springing its colors upon the ecology of learning. This much we know to be true: the nature of exploration, discovery and learning is no difficult journey. It is not carried well by compulsion or inspired by fear, nor is it informed by pain. True wisdom, true creativity, true learning, true teaching—are formed by an act of love. Metagogical teaching and learning is simply and completely an act of interdependent sharing—a sharing of secrets, of wisdom, of creativity, and of dreams great and small.

References

Amabile, T. (1983). The Social Psychology of Creativity. New York: Springer-Verlag

Amabile, T. (1988). Growing Up Creative: Nurturing a Lifetime of Creativity. New York: Crown.

Beck, D. & Cowan, C. (2006). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change. Carlton Victoria, Austrailia.

Beck, M., & Malley, J. (2003). A Pedagogy of Belonging, The International Child and Youth Care Network (CYC-NET), 50. Retrieved from http://www.cyc-net.org/cyc-online/cycol-0303-belonging.html

Berens, L. (1990) Introduction to Temperament. Huntington Beach, CA: Telos

Publications.

Boucouvalas, M. (1988). An Analysis and Critique of the Concept of Self in Self-directed Learning: Toward a more Robust Construct for Research and Practice. In M. Zukas (Ed.), Papers from the Transatlantic Dialogue: SCUTREA 1988 (pp. 56-61). Leeds, England: School of Continuing Education. University of Leeds.

Breathnach, S. (1995). Simple Abundance: A Daybook of Comfort and Joy. New York, NY: Warner Books, Inc.

Brookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. (2000). The Skillful Teacher. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Buscaglia, L. (1978). Personhood: The Art of Being Fully Human. Thorofare, NJ: CB Slack.

Carver, C. & Scheier, M. (1996). Perspectives on Personality (3rd Edition). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Cook-Sather, A. (May, 2002). Authorizing Students’ Perspectives: Toward Trust, Dialogue, and Change in Education, Educational Researcher, 31(4), pp. 3-14.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper.

Epstein, M. (1999). Theses on Metarealism and Conceptualism, In M. Epstein, A. Genis, & S. Vladiv-Glover, (Eds.), Russian Postmodernism: New Perspectives on Post-Soviet Culture, 105-112. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books

Frost, R., & Richardson, M. (2007). The Collected Prose of Robert Frost. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gardner, J. (1990). On Leadership. New York: The Free Press.

Glasser, W. (1986). Control Theory in the Classroom. New York: Harper & Row.

Greenleaf, R. (1977). Servant Leadership. New York: Paulist Press.

Gronlund N. (1995). How to Write and Use Instructional Objectives (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill.

Gronlund, N., & Brookhart, S. (2008). Gronlund’s Writing Instructional Objectives (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Halpern, D. (2003). Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking, (4th ed.), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hennessey, B., and Amabile, T. (1988) The Conditions of Creativity. In The Nature of Creativity, R. J. Sternberg (Ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kelly, R. (1992). The Power of Followership. New York: Doubleday.

Knowles, M. (1973). The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Houston: Gulf.

Knowles, M. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy, (Second ed.), New York, NY: Cambridge Books.

Knowles, M., Holton, E., & Swanson, R. (2005). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, Atlanta, GA: Elsevier.

Kolberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive developmental approach to socialization, in Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research, D. A. Goslin, Ed., Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 347-480.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego Development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Maslow, A. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, pp. 370-396.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper.

Maslow, A. (1965). Eupsychian Management: A Journal. Homewood, IL.: Dorsey.

Maslow, A. (1968). Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Maslow, A. (1971). The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Viking Press.

Maslow, A. (1974). Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences. New York: Viking Press.

McCaslin, M. & Snow, R. (October, 2010). The Human Art of Leading: A Foreshadow to the Potentiating Movement of Leadership Studies. Integral Leadership Review..

Merriam, S., & Caffarella, R. (1999). Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. (SecondEd.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S., Caffarella, R., & Baumgartner, L. (2007). Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide, (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1996). Contemporary Paradigms of Learning, Adult Education Quarterly, 46(3), 158-172. doi: 10.1177/074171369604600303

Moffett, J. (1994). The Universal Schoolhouse: Spiritual Awakening through Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Norton, D. (1977). Personal Destinies: A Philosophy of Ethical Individualism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Parini, J. (2000). Robert Frost: A Life. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Strengths of Character and Well-being, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-619.

Pratt, D. & Associates (1998). Five Perspectives on Teaching in Adult and Higher Education. Mirabar, FL: Krieger.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions, Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (2008). Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-being, Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, pp. 13-39, DOI 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0.

Schank, R. & Childers, R. (1988). The Creative Attitude: Learning to Ask and Answer the Right Questions. New York: Macmillan.

Scrimsher, S., & Tudge, J. (2010). The Teaching/Learning Relationship in the First Years of School: Some Revolutionary Implications of Vygotskya’s Theory, 14(3), Early Education & Development, pp. 293-312.

Scott, K. W. (2004). Collaborative Self-direction: Two Approaches. Vertex: The Online Journal for Adult and Workforce Education, 1(1), http://vawin.jmu.edu/vertex/article.php?v=1&i=1&a=4.

Shapiro, N. & Levine, J. (1999), Creating Learning Communities: A Practical Guide to Winning Support, Organizing for Change, and Implementing Programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Spears, L. (ed.) (1995). Reflections on Leadership. New York: Wiley.

Spears, L. (ed.) (1998). The Power of Servant Leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Stevens-Long, J., & Commons, M. (1992). Adult Life: Developmental Processes. (4th Ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Tisdell, E. (2003). Exploring Spirituality and Culture in Adult and Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Goal Contents in Self-determination Theory: Another Look at the Quality of Academic Motivation, Educational Psychologist, 41(1), pp. 19-31, DOI: 10.1207/s5326985ep4101_4.

Vvyotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walsh, R., & Vaughn, F. (1993). The Art of Transcendence: An Introduction to the Common Elements of Transpersonal Practices. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 25, 1-10.

Webb. L., Metha, A., & Forbis Jordan, K. (1991). Foundations of American Education, New York, NY: Macmillan.

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wheatley, M. J. (1992). Leadership and the new science. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

About the Authors

Mark McCaslin, PhD, is a career educator with a rich history of teaching, educational programming, and administration. His personal and professional interests flow around the development of philosophies, principles, and practices dedicated to the full actualization of human potential. The focus of his research has centered upon organizational leadership and educational approaches that foster a more holistic approach towards the actualization of that potential. At the apex of his current teaching, writing, and research is the emergence of potentiating leadership and the potentiating arts.

Karen Wilson Scott, PhD, is a professor of Human Resource Training and Development at Idaho State University. Her research and practice focus on adult learning, learner-centered teaching, and self-directed learning with an emphasis on congruous autonomy. She is particularly pursuing understanding of independent vs. interdependent learning, and the importance of community in fostering metagogy within and through second-tier teaching and learning. She serves as an adult teaching and learning consultant, a member of lifelong learning and self-directed learning professional organizations, and a Co-Editor of The Qualitative Report.