Nick Ross

No, my heart is not asleep.

It is awake, wide awake.

Not asleep, not dreaming—

its eyes are opened wide

watching distant signals, listening

on the rim of vast silence

Antonio MachadoHere is my secret. It is very simple.

It is only with the heart that one sees clearly.

What is essential is invisible to the eye

Antoine de St Exupery

Overview

In his first paper Nick Ross presented a model of interpersonal leadership that highlighted the significant gap between what business expects of its leaders and the capacity for leaders to meet those expectations.1 To close the gap, Ross proposes that leadership development requires a fundamental re-imagining of the relationship between the ego and the transpersonal self as essential mediating functions between the objective, external world and the subjective inner world. Developing a healthy relationship between the ego and the transpersonal perspectives is essential in developing skilful, transformative leadership practice. Developing greater complexity — becoming mature leaders — does not mean simply developing more intellectual capacity — getting smarter and faster at what we already do. Additional to the development of greater intellectual expertise there is a requirement to expand and deepen both psychologically and spiritually in ways that move beyond certain cultural, environmental and self-imposed limits relating to the understanding of self and consciousness in western society. Psychological depth and spiritual maturity represent legitimate developmental goals for executive education that encourage the emergence of a wider spectrum of knowledge, understanding and wisdom and that develop levels of mental complexity concomitant with ideas developed by Kegan and Lahey and explored in the first paper, of the self-transforming mind. The paper is divided into two parts. In Part 1 Ross examines the case for a broader educational curriculum and sets of premises for further discussion. In Part 2 Ross presents an emergent model for an alternative curriculum and three short reflections on the practice of interpersonal leadership aimed specifically at developing the transpersonal self.

Part 1:

1.1 Introduction

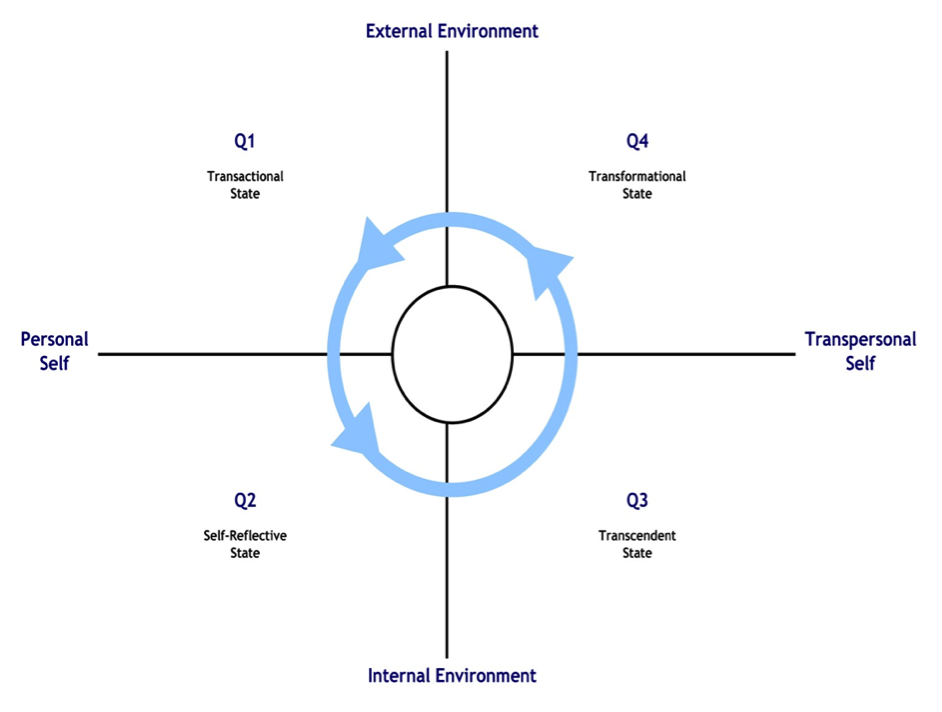

In setting out the model of interpersonal leadership development I have proposed that there are two pairs of important relationships that need to be considered in any programme of executive education that aims to develop its students in the direction of significantly greater complexity and maturity. The relationships I refer to (Figure 1) are between the external world and the student’s internal world (Y axis) and between the student’s ego self and transpersonal self (X axis).

The term interpersonal reflects two important features of the model. Firstly, interpersonal refers to the potential for enhanced levels of coherence between the mind-states referred to here. The aim of development in general terms is to facilitate a greater capacity for shifting one’s centre of gravity across and between states as changing contexts require. Greater complexity (defined as maturity of response) is recognised here as a greater capacity for flexibility and adaptability within and across states.

Secondly, interpersonal refers to the developmental input itself. It describes the nature and substance of an enhanced executive curriculum, which would necessarily be multi-disciplinary, non-traditional and diverse in nature, giving students access to the broadest possible array of data and material best suited to meet their developmental needs.

We access different mental states through our capacity to rotate our consciousness consciously across and between the perspectives of the ego and transpersonal self, two distinct and complementary ways of understanding self and other. The purpose of developing this capacity is to promote a state of health in the individual, broadly defined as the experience of states of inner wholeness, supporting activity in the world guided by a sense of moral agency.

For the purpose of this paper, the ego is oriented to processes related to the activity of our brain-mind and represents the seat of our Intellect. The intellect is rational, particular and independent. We can define the intellect as:

A head based operation incorporating ever more complex variations and applications, each needing further explication and qualification. 2

The transpersonal self is oriented to the heart and is the seat of a quality of Intelligence that is unitary, holistic and interdependent: We can describe intelligence here as:

The automatic and natural state of the heart which brings coherence.3

Coherence within and between states is critical to well-being. One assumption in this paper is that our hearts think and feel intimately in ways that are at once very different to the intellect but that both (in states of health) are connected through systems of resonance and flow. It is well known that the hearts electromagnetic field oscillates out of the body as a torus surrounding and embracing the body itself and streaming out beyond the body for an indeterminate distance. The torus is strikingly similar to that emitted by our planet earth and the sun. The frequency of the standing heart wave is found to be 73cps. When the five human oscillators (heart, spinal column, skull, third & fourth ventricles of the brain and the brain cortex) are entrained to resonance together, the frequency is also 73cps. The earth’s gravitational field also resonates at 73cps 4. Positive emotional states such as love, empathy and compassion cause the human torus to oscillate in a state of high coherence. The field is disturbed and deregulated by emotional turmoil, upset and imbalance.

Put simply, it appears that we are profoundly attuned to the state of our relationships, both intrapersonally (within ourselves) but also interpersonally (with all living things). The heart at least, imagines the whole world to be alive and to be entangled in a reciprocal field of energy. Our capacity to experience the world as fundamentally alive impacts our own sense of aliveness in a direct way. Positive relationships and high levels of coherence are linked; intra-personally, interpersonally, globally and universally, in some meaningful way, we are our relationships. When our relationships are aligned we experience greater capability across an array of metrics. When our relationships are systemically out of alignment, we lose our centre, we feel at odds and our intelligence and capability suffers.

1.2 Being and Consciousness

I recently came across these words by Vaclav Havel spoken in 1990, a few months after Czechoslovakia freed itself from communist rule, to a joint session of the U.S. Congress:5

Consciousness precedes being, and not the other way around. For this reason, the salvation of this human world lies nowhere else than in the human heart, in the human power to reflect, in human meekness and in human responsibility. Without a global revolution in the sphere of human consciousness, nothing will change for the better…and the catastrophe toward which this world is headed—be it ecological, social, demographic or a general breakdown of civilization—will be unavoidable.

Havel’s words are important as we look to deepen our understanding about the qualities of the self-transforming mind. Havel is certainly commenting on particular qualities of leadership, but he ties those qualities and associated virtues to a particular quality of consciousness that transcends personality and private concerns in favour of a more global orientation. He also reflects on the tension between consciousness itself and action in the world. Each of us is consciousness and being but, as Havel says, Consciousness comes before Being; the forms we are and the forms we create as reality ‘out there’, arise from a certain quality of awareness ‘in here’.

The movement from form to formlessness is reflected elsewhere; for example in David Bohm’s ideas of the implicate and explicate order in physics and Carl Jung’s concepts of the conscious and unconscious pertaining to psychology. The idea of movement across borders is a central theme of this model, the movement between the ego and transpersonal states providing us with a further example of the impulse towards transition and evolution that seems to be inherent at every level of the Universe.

Havel implies a second critical point: the potential for movement into a different level of thinking is inevitably influenced (constrained and limited) by the thoughts, feelings, language, metaphors, models, maps and frames through which we reference and make sense of the world. There must be willingness to change and recognition that change is needed if evolution is to overcome inertia. When we are prepared, as Havel says we must be, to negotiate the borders of our consciousness towards new and different ways of thinking and being together, authentic creativity becomes possible. Failure to bridge the gap will only serve to prove Einstein’s point that the problems we face today could not be solved with the thinking that created them; the result of our inability to evolve, as Havel says, could be of great concern.

We must be prepared to re-imagine both our roles and responsibilities to the widest context we can imagine, as part of a community as global citizens. To do this we must be able to reference and engage with both ourselves and the world in new and different ways.

1.3 Premises for Discussion

To develop the discussion I would like to put forward three premises:

- Any dominant worldview will profoundly affect the formation of the philosophy, values and customs that support the maintenance and perpetuation of that worldview within a given culture. Our worldview strongly influences the ways in which we learn and come to know both self and world, including the formation of a sense of self, the ways we mediate reality, the values we adhere to and what we choose to include or discard in the world as ‘evidence’ of what is real and important. In Western society, reality is defined by the scientific method, which favours materialism and includes objectivism, rationalism, empiricism and positivism as central to developing understanding. What is deemed ‘real’ is to a great extent defined by what can be measured, examined and experienced through the senses consistently and with repetition.

- There are stages of human development recognised across all cultures running between birth and death including infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, mature adulthood, and eldership. Different cultures explain and support the transition across these thresholds in life in different ways and place differing levels of value on each stage. Thresholds include birth, puberty, marriage, childbirth, middle age, eldership and death. Within the Western worldview youth and youthfulness is given greater value throughout life whilst rites of puberty, transition through middle life, eldership and death receive markedly less attention and in many cases are hidden, ignored, misunderstood or avoided as being unimportant or not meaningful concerns. This view creates limitations within the Western paradigm that inevitably constrain growth towards levels of maturity beyond a certain stage of development. These limitations further reflect the relatively low value given in Western society to the integration of experience within meaningful psychological and spiritual frameworks and the relatively high value placed on personality, individualism and the drive for perfection.

- Psychological depth and spiritual maturity, as methods for extending and deepening our awareness of self and other, represent two legitimate and essential developmental goals in the progression towards mature adulthood. This is recognised by numerous cultures across the world. Careful development of these systems of learning could enhance existing educational programmes in the direction of greater complexity in ways that continue to honour critical values held by the culture such as secularism.

If we accept the premise that existing executive education within a Western framework is limited in some significant way by the existing paradigm that supports it, (as evidenced by the low number of otherwise bright individuals who are able to expand from the socialised mind towards self-authoring and then self-transforming stages of development,) we are then faced with a series of considerations relating to processes and practices that might improve things.

My central argument is that growth beyond a certain point of complexity requires a diversity of input that cultivates the self in new and different ways to those identified as key objectives in early career development. Beyond a certain point growth becomes less defined by extrinsic goals, the need to demonstrate effectiveness and gain success in pursuit of ideas of self-idealisation. These goals are of course legitimate within a socialised mind framework though there is considerable scope for development even in this area. However, with maturity and experience there is a tendency — innate in most people — to orientate towards goals related to questions of meaning, self-realisation and wholeness, a process that becomes more nuanced with time. This changing emphasis, especially in the phase we call middle life, whilst given less value within Western society is nonetheless a natural and essential progression that has both psychological and spiritual components.

1.4 Psychological Depth

Psychology refers to soul wisdom or soul knowledge. Psychological depth reflects the mature development of a sense of self, the integration of the many aspects of who we are brought into some kind of dynamic balance through careful reflection and honest analysis in the direction of greater meaning. Its orientation is towards a sense of wholeness gained through a process that includes deepening levels of introspection, reflection, integration of ‘other’, recognition of limitations and self-acceptance. ‘Other’ refers here to, ‘that which is unfamiliar or unknown in our inner or outer realm’ 6

When psycho-logos is well developed in the individual, it supports cultivation of a radical state of well-being. James Hillman rightly points out that psychology is something that must be gained for it is not given.

Pyschology…is not given…but…without psychological education we do not understand ourselves and we…suffer. 7

Psychology is essential to our wellbeing and it has an inward trajectory. We develop our psychology by developing our interiority and exploring the images, stories, dreams, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes that speak to our psychic condition. Jung described this as the journey towards individuation and it implies the cultivation of a different level of consciousness

All the greatest and most important problems in life are fundamentally insoluble…they can never be solved but only outgrown…This outgrowing, as I formerly called it, proved on further investigation to be a new level of consciousness. Some higher or wider interest appeared on the patient’s horizon, and through this broadening of his or her outlook the insoluble problem lost its urgency. It was not solved logically in its own terms but faded out when confronted with a new and stronger life urge’8

1.5 Spiritual Maturity

Spiritual maturity means the realisation of a life that has been led fully towards a certain quality of maturity and richness; Joseph Campbell described spirituality as;

The bouquet, the perfume, the flowering and fulfilment of human life, not a supernatural virtue imposed on it. 9

In defining spiritual maturity further I return to the concepts laid out by David Lane in the first paper regarding spiritual Intelligence: that evidence of spiritual development is reflected in our capacity to explore the deep existential questions of life, develop meaning for ourselves over time irrespective of changing circumstances and to develop and explore expanded states of consciousness beyond the position of the ego personality, to learn to live and work whilst navigating the relationship between expanded states of awareness (the capacity to live expansively and interdependently) whilst be engaged in purposeful activity in the world. Spiritual maturity describes a certain state of presence to the world rather than the embodiment of a certain set of rules. In this context it has to do with our capacity to see the world as Sacred, where sacred is defined as ‘worthy of respect.’ 10

If we are willing to agree that current educational programmes are inadequate to meet the need to expand people towards greater levels of complexity, and if we can agree to the idea that Psychological depth and spiritual maturity provide legitimate developmental goals, then two further reflections become important.

How do we understand the current situation?

What might be included within a new interpersonal curriculum?

1.6 The Situation Today: Evolution and Limitation

Human beings are complex living systems that demonstrate a tendency towards growth in general terms given the right conditions. All growth and development towards greater levels of complexity, be it personal or organisational, takes place in an iterative way, a process that Joseph Chilton Pearce describes as stochastic11 — meaning purposeful randomness. Imagine a continually oscillating movement between two complementary impulses. The first is towards evolution — the transcendent aspect of creation that first identifies and then pushes us to go beyond existing limitations and constraints. The second impulse — the act of creativity itself — is the emergent process that gives new form to the transcendent urge in the world. The pattern of movement that this describes is important. Whilst there is a certain sense of linearity in the evolutionary impulse, something we experience in terms of our concept of time (past to future) and pathways of personal development (birth and childhood to adulthood, old age and death) the movement is at the same time cyclical, describing a pattern in our actual experience of growth, maintenance, collapse, and change: endless cycles, with the whole movement tending towards greater complexity over time.

We experience greater complexity and are able to face greater challenges only by outgrowing our existing worldviews, beliefs, biases, frames, maps and models. This inevitably creates a certain resistance to what is new and different. The impulse to transcend our limitations and constraints is both compelling and strangely paradoxical. We are forced to give up what we have made of ourselves — what we have striven and sacrificed and suffered to become in order to become something more or different, to become more complex individuals. Change is not easy. Better the devil you know is more than a simple truism. With time we will come to know the territory of change more intimately, but change — specifically that which is evolutionary in nature — invariably forces us to engage in processes that can, at one and the same time, exhilarate, confuse, excite, depress and terrify us.

The cycle of evolution and creativity is constrained by the dominant worldview that we reference, the definition of reality that it supports and the educational system that underpins its continued existence. In a society dominated by a particular orientation refereed to often as left brain dominant, we find ourselves in a hall of mirrors constructed and then maintained by the brain itself towards certain ends. Anomalies are rejected and certain ways of seeing the world are simply taken as assumed truth. Within this framework, early stages of career development happen quite organically because they are supported by social and philosophical frameworks in which particular qualities useful in organisations are both encouraged and rewarded. Conventional learning is delivered as instruction based on objective facts. Such learning is of course an important part of the cycle of development towards greater complexity. Each of us must learn to value and understand the systems through which we can become useful and productive members of society. We must learn the rules.

Difficulties arise when developmental needs take the person beyond the terms of reference that are dominant within the culture. There is a time when learning requirements inevitably become more subjective and diverse. At a certain point, given the natural limitations and constraints of the system, learning must become a determined, conscious choice on the part of the individual since it ceases to become a simple bi-product of attendance. Such a decision requires a leap of faith and existing systems offer little encouragement for such a leap. This becomes ever more problematic as learning needs become more nuanced in the direction of managing greater ambiguity, cultivating multiple frames of reference for the external world and developing a degree of inner quiet etude, all traits concomitant with the self-transforming mind. On these subjects current educational programmes simply fall silent.

A final challenge reflects a limitation inherent in ideas of authentic transformational development work itself, something that requires further discussion and which sits outside the scope of this paper; Personal work is hard to do. It is the ego’s preference to move fast, to get things done, get fixed, strive to the end, win, go it alone. The transpersonal world is very different. Transformational change cannot be forced. It’s another way of saying there are no techniques. Nothing can railroad things like soul into the world. The tendency from an intellectual perspective is to imagine that each threshold of growth can be negotiated through the mind alone. The point here is that there is a moment on the journey when the intellect is no longer sufficient to the challenge. Psychology and spiritual maturity has its orientation to the heart and to a certain quality of vulnerability that the ego will reject. To become more means that we have to risk more and this is a threshold that cannot be negotiated unless it is a conscious choice. At a certain point we must really want to change.

PART 2 2.1: Towards a New Curriculum

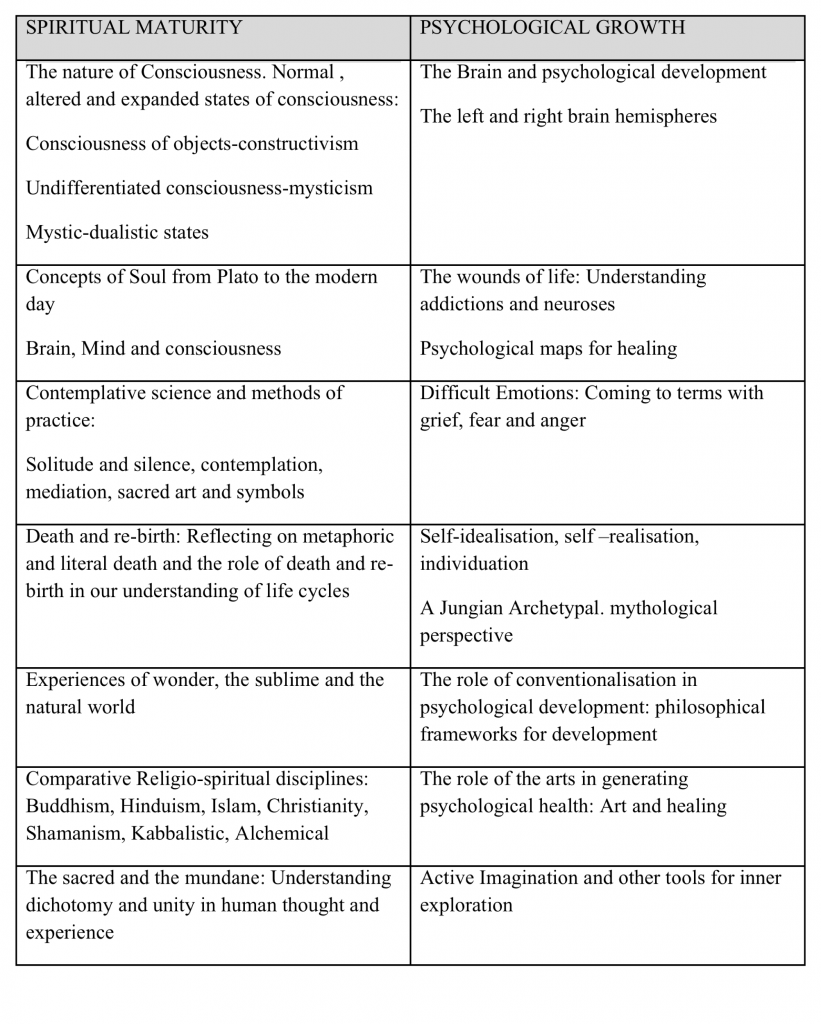

The development of psychological depth and spiritual maturity as will require a multi-disciplinary approach to support learning objectives across a broad array of subjects: Whilst far from an exhaustive list, subjects for future consideration might include the following areas:

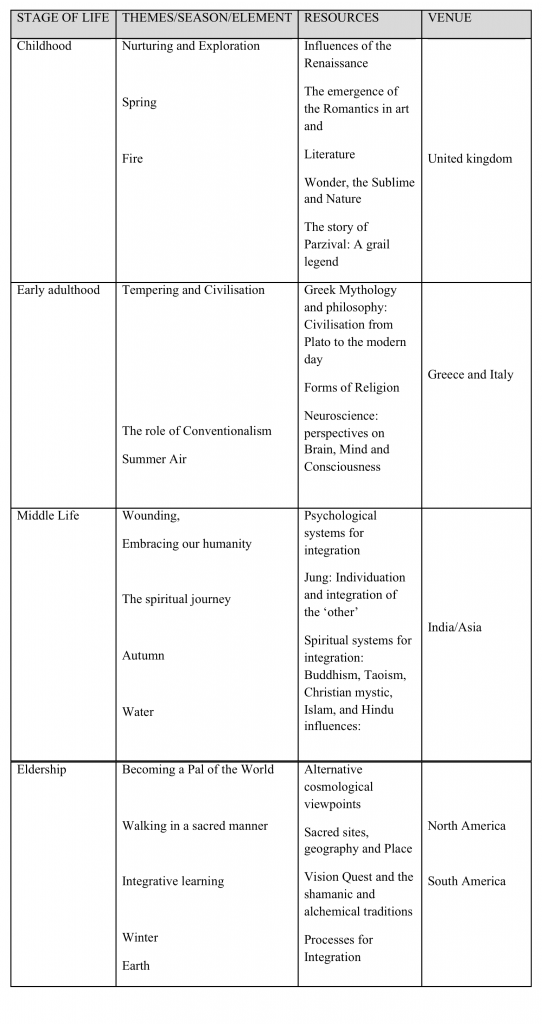

In terms of the curriculum emerging in my own practice; the following framework, delivered over a period ranging from one week to one year is outlined in Table 2. The programme is oriented around specific stages of life and is cyclical. I have included venues because I have found that place supports learning significantly. People interested in further details of the curriculum and the emergent model can contact me directly.

Wilderness and Civilisation: A Metaphor for Learning

In order to better understand the sense of dynamic movement that takes place between the ego and transpersonal self within an enriched learning environment I want to propose a simple metaphor to hold in mind as a platform for the rest of this discussion. As we have seen, this is a model that speaks to two key pairs of relationships that exist in each of us; between the objective, external world and our subjective inner world and between our ego consciousness and transpersonal self as ways in which we can mediate our experience. To move between the relationships is to cross a frontier between quite different perspectives on the world. In his book, The Practice of the Wild, Gary Snyder speaks about the tangible difference at the frontier that marks the transition from wild to civilised places:

There is an almost invisible line that a person of the invading culture could walk across: out of history and into a perpetual present, a way of life attuned to the slower and steadier processes of nature. 12

To develop and evolve is to cross frontiers many times over a lifetime. I suspect that Snyder’s analogy reflects one of the truly profound movements that we must come to embrace as adults: to move with freedom back and forth across the borders between the ever present natural world — the transpersonal wilderness of our lives — and the organised construct within which we live in the world day to day as civilised people, the reality we call civilisation.

Metaphorically, the realm of the ego is represented by civilisation. The transpersonal or universal self is represented by wilderness. We learn to meet the world and ourselves from both places. We each must claim our place in the civilised world; it is a place for our talents, our intellect and our relationship with the ‘other’ in all its forms within a context that is subject-object oriented. ‘Here I am.’ ‘There you are.’

To develop beyond a certain point, I propose that we must also claim our place in the wilderness; intuitively we know it as a very different environment — out of time, ever present and critically, home to a different quality of our nature, a certain shy intelligence that has much to do with a sense of heart, and soul. If we were to agree that intimacy with soul (however one chooses to name or define the term) is of primary importance to a richly experienced and ultimately productive life, if we agree that the relationship between soul (depth of inwardness) and role (expression in the world) is central to authentic creative presence in the world as leaders, then coming to an authentic relationship with wilderness matters.

With this metaphor in mind I will explore three subject areas that highlight in different ways, aspects that aim to support transpersonal development. Though there is considerable scope for improvement, I am allowing for the fact that programmes aimed at enhancing the capacities of the ego are already reasonably well catered for. I will explore each subject in brief and at the end of each section I will raise considerations for further discussion. The subject areas are:

- The Human Brain and early childhood development

- Learning from alternative cosmologies

- The role of the arts in psychological and spiritual development

2.2 The Brain and Early Development

Our development begins with our birth and our early childhood and it begins with a certain quality of wildness: the emergence of a quality of Spirit that is us — into the world.

We are natural beings with an inherently wild aspect to our nature. The word nature, shares its root with the word natal or birth; we arrive as creatures of the world but not yet as personalities. We show up fully immersed in the universal state, a state of immersion — what Jean Piaget described figuratively and literally, as ‘dream children’ — and we emerge only slowly from the field into the world of sense, form and conscious awareness. At birth and for some time afterwards we live in a state of undifferentiated consciousness very much like the dreaming state as registered in an adult by an EEG.13 As we slowly arrive into our bodies, as we become more solid, we do so as profoundly curious creatures with an innate desire to explore the world around us. At the same time we need the unreserved nurturance and comfort that our caregivers provide.

Joseph Chilton Pearce proposes that there are two fundamental inner directives within every child that must be attended to for healthy development: to maintain nurturing contact with their caretaker (usually the Mother) and to have the freedom to explore the world ‘out there’.14 It is these conditions that give rise to a healthy child and that form the template for future development. Michael Oakeshott puts the imperative this way:

None of us is born human, each of us is what we learn to become. 15

We are born as potential — a word that has its root in the Latin Potentia meaning power. We are not born as complete beings; rather we emerge through an endless process of becomings. Nurturing and exploration are the essential iterative movements of very early childhood, the root from which all subsequent growth takes place. A healthy relationship between these two directives is central to the healthy development of the human brain.

Nurturing proves to be not only the way by which the human species arose out of its animal ancestry; it proves to be the only way which we evolved creatures can then be fully developed from conception to maturity. 16

Under healthy conditions the human brain evolves as a fourfold process of integration. The first neural system to develop is the reptilian or ‘world’ brain, the system that is concerned with our capacity to sense the physical world and to survive in it, determining food from threat and taking necessary action to find one and avoid the other. The second evolutionary step sees the development of the old mammalian brain, giving us our capacity to interpret what is happening in the world in terms of our relationships with other objects. This capacity for relatedness supports development of the third structure, the new mammalian brain that imbues our sense of relatedness with meaning and significance. Within this third neural system, the neo-cortex, we find the development of an emotional framework that allows us to work together, to build tribes, to develop thought and speech and to think in abstract ways. From here we learn to create our views and maps of the world ‘out there’. The establishment of these three capacities give rise to the fourth system, our coordinating brain or ‘governor,’ the prefrontal cortex.

The development of the neo-cortex and its role in our capacity for knowing self and universe is both central to the development of the optimal mind states proposed in this model and central to the development of the self-transforming mind in general terms. Our brains development is the process of the impulse towards evolutionary growth. Each neural system builds on the one prior to it whilst simultaneously creating the conditions for the emergence of the following stage. With each stage development, a process that takes place in the first couple of years of life-we experience at first hand this transcendent principle that is so central to life. The emergence of the prefrontal cortex gives us the gift for complex levels of organisation; we can organise the qualities inherent in the other systems into a state of coherent focused attention and response that is imaginative, original and creative;

Above all the fourth brain is capable of creation in a literal sense, first creating internal images not present in the outer world (creative imagination) then concretising such inner images in the outer sensory world shared with others.17

Failure of this developmental process either through a lack of nurturing (leading to a sense of abandonment in the child) or an inability to explore the world for whatever reason, or both, compromises this process of healthy development with potentially disastrous and long term results;

An infant born and not nurtured, particularly in the critical first year will remain largely locked into his primary defensive sensory motor brain, since his emotional system is then truncated and events in his environment cannot be fully integrated. Instead these events bring further retreats into his defensive system. He armours against the world from the beginning, rather than relating to the events of the world.18

Early life is about the emergence of a certain quality of free energy or spirit and the experience of life through that spirit. Inevitably we are all subjected to forces that handicap and wound that spirit; events and experiences and contexts shape us in ways that mean the spirit is never really cultivated and brought forward. In healthy circumstances the forces of life are allowed to run through the child and this is essential for as spirited children we rarely do great harm to anything. The energy of life takes the child up. The same cannot be said of that same spirit in the hands of adults who do not fully understand it, have not developed a constructive relationship with it in early life and do not know how to call it down from the heavens when needed.

When development is compromised a kind of inverse evolution takes place in the brain itself. Perhaps society damps the spirit down too fast; the child cannot explore the world fully enough or does not feel safe to do so. In terms of brain development the prefrontal cortex — the governor of the whole system whose role it is to organise the mind brain into a profound quality of attention that could support our on-going evolutionary development — is bent back on itself into service of the lower but more powerful drive for survival represented by the first ‘world’ brain. The highest finds itself in service to the lowest and then uses the extraordinary rationality inherent in the highest system to justify its ongoing actions in the world. As Pearce put it;

There is nothing more dangerous and destructive than a brilliant, genius level reptile.19

The entire field of psychoanalysis has emerged to manage the neuroses that arise with the repression of the spirit in early and later life. As Sigmund Freud pointed out, the cost of civilisation is our neuroses.

If the development of civilization has such a far-reaching similarity to the development of the individual and if it employs the same methods, may we not be justified in reaching the diagnosis that, under the influence of cultural urges, some civilizations, or some epochs of civilization — possibly the whole of mankind — have become “neurotic”? 20

Developmental Considerations might include:

- Creating subjective understanding of the role of nurturing and exploration in early childhood development.

- Recognising the subjective impact of childhood constraints on natural development in terms of emerging values, thinking, behaviour and subsequent life choices.

- Discussion of the connection between civilisation and neurosis and the psychological practices that explore and address this tension.

- Development of processes that encourage bottom up thinking such that the ‘world’ brain functions in service to the higher level of the neo-cortex and not the other way around.

- Identifying methods that enhance optimal balance between left and right hemisphere functions including enhancement of skills in the fields of awareness, attention flow and conscious use of the parasympathetic nervous system in controlling emotional states.

- Developing opportunities for the practice of creative imagination and the exploration and expression of higher order values including sympathy, altruism and love associated with higher brain functions within appropriate group environments.

- Methods for supporting the healthy transition between early experiences of our spirited nature and the tempering of that nature within a system of virtues and values indicated by the initiatory experience of adolescence and the later arrival of early adulthood.

2.3 Alternative Cosmologies

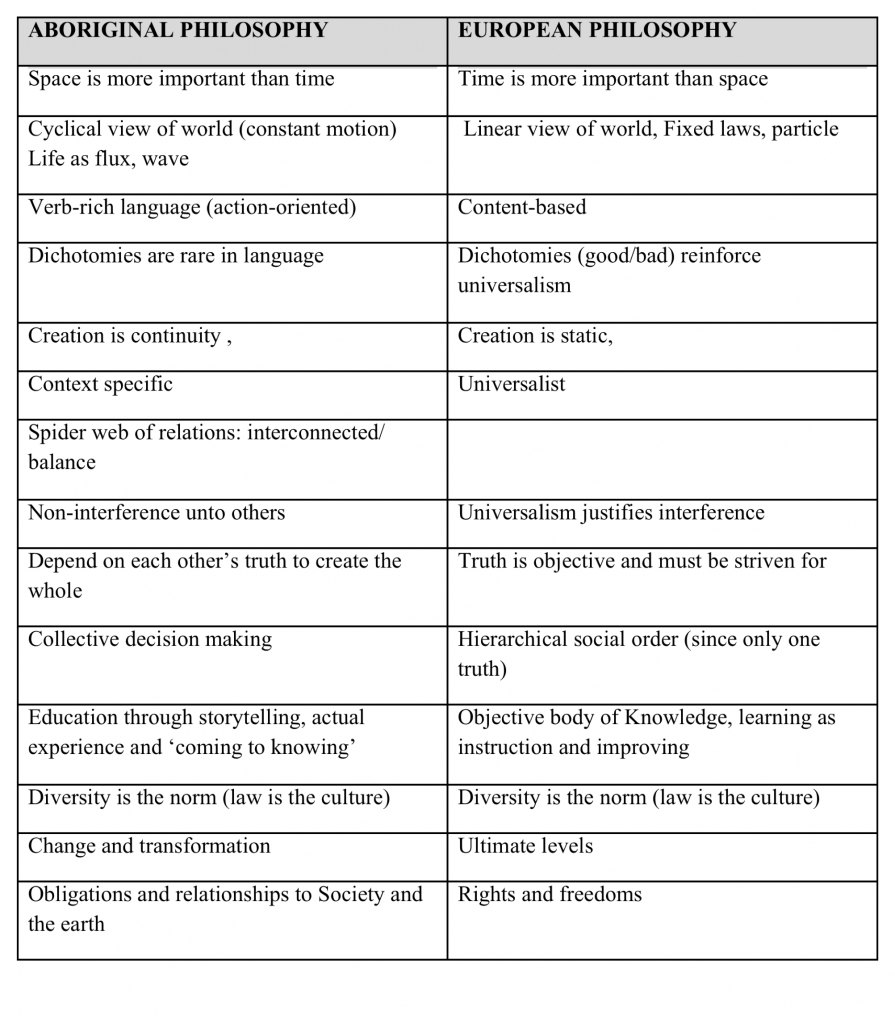

To enrich our understanding of the transpersonal aspects of self requires that we be prepared to transcend the limitations of the dominant worldview within which we live. In Western society the worldview has its primary orientation towards rational, linear thinking, objectivism and positivism, a set of assumptions for understanding reality that continue to underpin traditional executive development today.

Different languages are appropriate to different rhythms of consciousness. There are worldviews, maps and models thousands of years old that hold as central the belief that we live in a participatory universe that is alive, intricately networked, and reciprocal. These cosmologies offer, literally and metaphorically, a different language through which we can come to see and understand the world in broader terms.

According to many Native cosmologies including that of the Plains Indians of North America, the tendency of this living universe is to move in cycles of evolution and creativity, not in linear form. As active participants in a world that is ever unfolding it is assumed that we carry a high level of creative and moral agency. We are in an interdependent relationship with all living things. We are actors in the world and our participation represented by the movement between our emergent subjective understanding and our outward expression matters tremendously. Our capacity for agency implies a level of significant responsibility as partners in an evolving world and supports a framework for living that is at once collaborative and imbued with a sense of self-discipline. A profoundly different worldview such as the one outlined here has implications for the wider culture that it both forms and informs, the philosophy it espouses and the educational practices that emerge naturally from such a philosophy.

In a western culture our natural tendency is to warn, help, teach, instruct and improve. In the native world you cannot ‘give’ a person knowledge — each person learns for himself through the processes of growing up in contact with nature and society by observing, watching, listening and dreaming.21

How might we create an educational practice that incorporates subjective experience as legitimate evidence, one in which observing, watching, listening and dreaming are encouraged as genuine learning methods? Essentially alternative cosmologies invite us to move towards a wider and richer spectrum of learning that values subjectivity alongside or in favour of objectivity and that could include a very broad array of data as ‘evidence’. From a native perspective there is intelligence in everything since everything is alive and imbued with consciousness according to its own capabilities. Song, symbol, dreams, birds, shooting stars, metaphysical and synchronistic events connect us to that which is hidden, implicate, unconscious. The cosmological view of the plains Indians is reflected in many other disciplines including depth psychology, the arts, mythology, mysticism and new science. At heart it states: “There is more to the world than meets the eye”. From a native perspective, the world is energy, animate, imbued with spirit and in constant motion.

The poet WB Yeats put it differently when he said,

The world is full of magical things patiently waiting for our senses to sharpen. 23

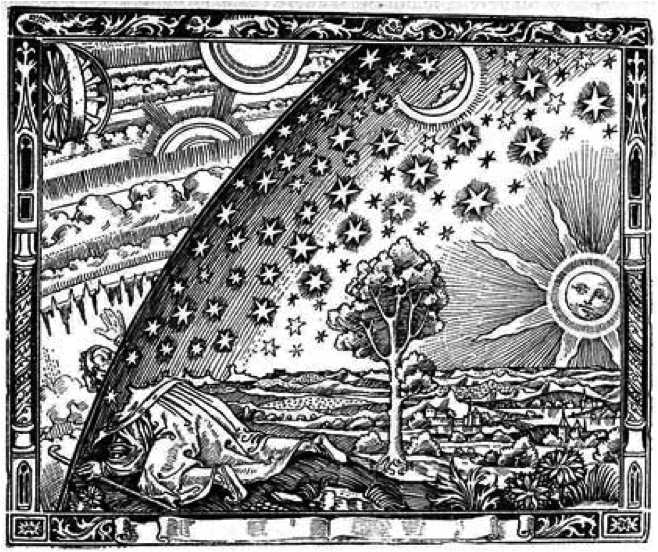

The physicist David Bohm spoke about the idea of the implicate and explicate orders. Psychologically, we talk about the nature of the conscious and the unconscious — that which is known and that which is ‘other’; psychic tendencies hidden from our sight, in shadow, personally or collectively, but intimated to us in our dreams, stories, legends, fairy tales and synchronicities that can be touched directly through certain kinds of education, reflection and personal work. Spiritually, mystics point to the ‘mystery’ in which we find ourselves. They talk of the mundane, the natural, the ordinary, on one hand, the transcendent, sacred and extraordinary, on the other, and then explore the relationship between these worlds through an array of methods such as contemplation, meditation, solitude and prayer — vehicles that help to carry them between the mundus and the holy, from the dichotomous world of subject-object and material to the unitary and immaterial world of spirit. In Figure 5, a wood engraving by an unknown artist first published in Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire, we see a wanderer crossing worlds; a metaphorical image of mystical and scientific discovery.

Figure 2: Woodcut from Camille Flammarion’s Book Published in 1888 L’atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire,

Figure 2: Woodcut from Camille Flammarion’s Book Published in 1888 L’atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire,

Different cosmological worldviews alongside the arts, science, psychology and spiritual disciplines each say in different ways that we can expand our sense of ourselves beyond the viewpoint taken up by the ego alone and that this expansion adds value to our life experience in the form of the expanded values we embrace, the intimacy of our experience in the world, the sense of meaning and purpose, personally and collectively that the journey towards mature adulthood provides. From this perspective maturity evolves as we discover and expand into more of the psycho-spiritual landscape of our lives. We can learn to ‘sharpen our senses’ in various ways, becoming available to much more of ourselves and the world but we tend not to do this due to a variety of constraints.

Developmental Considerations might include:

- How worldviews shape thinking and action: European, Aboriginal, Amerindian, Asian, Shamanic.

- The role of initiation, ritual, ceremony and place in recognising life transitions and connecting to ideas of the Sacred.

- Archetype and mythology: the role of story in building and sustaining culture and supporting psycho-spiritual health.

- The role of science, the arts, spirituality and psychology in interpreting the world including the experience of dichotomy and unity.

- Cultural perspectives on transpersonal experience and the nature of mind and consciousness.

- Neuroscience and the role of contemplative science in the development of mind.

2.4 Creativity and Education

In proposing practices for development that incorporate a broader view of the world as essentially moral, participatory and animate the arts, contemplation and nature are especially well suited as vehicles for learning, while both challenging and expanding our perception of ourselves and the world in which we live. Creativity, including the capacity for originality and discovery sits at the heart of mature leadership and the arts (poetry, prose, visual, dramatic) offer creative media that can readily give access to transpersonal states and challenge the mediocre thinking and mechanical reactions that can too easily stifle change and growth. Exploring self and world through the arts can greatly support learning and this is enhanced further by other activities and supportive environments, including time in the natural world, silence, solitude and contemplation, each of which has a special place in the development of inwardness.

Education at its best is a journey of discovery. Good education in its original sense sought to draw out our unique genius. At best it disturbs the biases, filters, maps, models and theories of practice that make up our sense of who we are and the world in which we live. It tests our relationship with the laws within which we operate and illuminates the cycle of evolutionary growth and creative expression that exists in each person.

In the many years that I worked in the field of addictions I experienced no more helpful times than those when we abandoned the talking in favour of other forms of expression such as drawing or writing — small groups drawing with pastels and charcoals, or speaking scribbled out poems and clumsy haiku, touching feelings and expressing absurd situations using body shapes and sounds. Sometimes, perhaps often, there are no words for the situations we face and the condition we find ourselves in. Certainly if I have learned anything it’s that I cannot know what another person actually needs or should do to change, though I have been very frequently tempted to guess and share my point of view full of conviction, usually uninvited. It seems so easy to know another person’s business and another person’s path to greater integrity or wholeness. I have come to be wary of easy solutions. And what is offered here is not offered in that way. The reflections offered below simply centre themselves on some of the things that I have found can help to illuminate the path with all that that might imply for a more integrated leadership practice. There are no quick fixes.

I will share two example of practice here. As readers you are very welcome to engage with the exercises if you wish. They are reflective in nature and are best supported by practices such as journaling. It is important to note that they are offered as examples of practice only. It is helpful to imagine that exploration of themes such as those explored here usually take place in small groups in quiet, supportive, natural surroundings. Place and context is extremely important. With that caveat I offer the following.

The first formed the basis of a conversation at a week-long retreat: The subject for the day was grief and the medium for learning began with a personal story and then a poem to support further reflection. In the process delegates were invited to listen to the story and the poem and to use them as vehicles to reflect on their own experiences. This led to very profound dialogue within the group around the subject of grief and loss.

The second example uses poetry again and relates to the emergence of the authentic transformational state, a state that is experienced here in two complementary ways: as transpersonal but with an orientation firmly towards a life lived fully in the world itself. The poem is a central feature of the retreats and acts again as a vehicle or container for subjective reflection on the subject of wilderness. The exercise is called, becoming a pal of the world.

First Story: Grief

Two years ago whilst delivering a leadership programme in Jerusalem, I went for a walk in the Old City with friends. It was my first visit and I had a troubled heart. My inner voice was agitating me tremendously and I experienced that agitation as a more or less physical pain. At root was the fact that whilst I was in Jerusalem working, my children were leaving home in the UK and I was not there to be part of that journey. It was a tremendous point of transition for all of us and I was not part of it as it seemed to me. This touched on a thread that led to all the other times that work had taken me away from important family commitments. I felt guilt but much more than that it was a time of tremendous grief. As I sat in the bowels of the Church of St Anne I was of a sudden overwhelmed with tears that became a torrent of sorrows. I sank into grief that layered itself onto other grief’s that were, so it seemed to me, the simple consequences of life lived and choices made. I was in grief. The guilt left with the tears and I was left with an experience of my own humanity, the impossibility that comes with the truth that one can never always ‘get it right.’ Whole but not perfect, I thought. Relief. It was a profoundly cathartic and healing experience made better since it was borne in the company of friends who simply witnessed me without trying to fix me or make it all better. Later that evening, my friend Will Ayott who was with me that day and who is a fine poet sat next to me in silence and handed me a copy of his latest small book of poetry with a little inscription inside the front cover: Jerusalem pp36. William left again. The poem on page 36 is called The Water Cage.

The grief came up unbidden, like water

Slowly percolating through the strata

Of the past. It found its level and stayed.It stayed through the iron days of work

And exhaustion, through the brittle days

Of disbelief and thoughtless solicitude.It dripped through the hollow nights

Spent clinging artfully to strangers

And leeched the hope out of crawling mornings.In staying it was joined by other griefs

That through the years had washed together

Grief on grief, eroding chasms and ravines.Until in time it was a stream of pain, a river

And at last a sea where I was held immobile

Drowning in a cage that was a second skin.The grief came up unbidden, like water

Slowly percolating through the strata

Of the past. It found its level and stayed. 24

Reflection for participants:

What are the consequences for you of a life lived and choices made that move you to grief?

Which writings (stories, poems etc) do you turn to that touch your experiences of loss, humanity and tough choices most closely?

Which people in your life offer you support that does not seek to fix, rescue or advise?

The purpose of this passage is to articulate a particular methodology using the arts — in this case poetry — for deepening dialogue around important subjects. Any artistic activities will aim to illuminate the quiet inward movement within each of us that can build greater psychological depth and spiritual maturity. James Hillman, we recall, said that Psychology is something that must be gained, for it is not given. He went on to say that without a psychological education we do not understand ourselves and as a result, we suffer. Finding and adopting means that support a practice of gentle deepening are essential to any new model of education.

Second Story: Becoming a Pal of the World

To be a pal of the world is to mature towards a certain quality of adulthood that reflects a profound coherence between the different mind-states put forward in the model. To be a pal of the world is to participate as agents in an animate, responsive world. This intimate phrase, with its implications for such a rich sense of connection, life and soul comes from the poem of that name by Carl Sandburg.

There is a wolf in me . . . fangs pointed for tearing gashes . . . a red tongue for raw meat . . . and the hot lapping of blood—I keep this wolf because the wilderness gave it to me and the wilderness will not let it go.

There is a fox in me . . . a silver-gray fox . . . I sniff and guess . . . I pick things out of the wind and air . . . I nose in the dark night and take sleepers and eat them and hide the feathers . . . I circle and loop and double-cross.

There is a hog in me . . . a snout and a belly . . . a machinery for eating and grunting . . . a machinery for sleeping satisfied in the sun—I got this too from the wilderness and the wilderness will not let it go.

There is a fish in me . . . I know I came from salt-blue water-gates . . . I scurried with shoals of herring . . . I blew waterspouts with porpoises . . . before land was . . . before the water went down . . . before Noah . . . before the first chapter of Genesis.

There is a baboon in me . . . clambering-clawed . . . dog-faced . . . yawping a galoot’s hunger . . . hairy under the armpits . . . here are the hawk-eyed hankering men . . . here are the blonde and blue-eyed women . . . here they hide curled asleep waiting . . . ready to snarl and kill . . . ready to sing and give milk . . . waiting—I keep the baboon because the wilderness says so.

There is an eagle in me and a mockingbird . . . and the eagle flies among the Rocky Mountains of my dreams and fights among the Sierra crags of what I want . . . and the mockingbird warbles in the early forenoon before the dew is gone, warbles in the underbrush of my Chattanoogas of hope, gushes over the blue Ozark foothills of my wishes—And I got the eagle and the mockingbird from the wilderness.

O, I got a zoo, I got a menagerie, inside my ribs, under my bony head, under my red-valve heart—and I got something else: it is a man-child heart, a woman-child heart: it is a father and mother and lover: it came from God-Knows-Where: it is going to God-Knows-Where—For I am the keeper of the zoo: I say yes and no: I sing and kill and work: I am a pal of the world: I came from the wilderness.25

Reflections for participants:

What are the animals, birds and fish that you carry inside you? How do they speak to you and inform your ways of seeing and being in the world?

What does it mean to you to say yes and no, to sing, kill and work? What does it mean to you to be a pal of the world and how does this affect your choices and actions at work?

What images, stories, poems or places connect you most deeply to the natural world, giving you a sense of place? How does this inform your sense of self?

We come from the wilderness and we return to the wilderness but we return as different people with a different regard for the world. I love this poem because for me it so fully captures a certain state of mature adulthood that makes a human being so alive and so effective. It is irreverent and yet sacred, it knows nothing but it shines with wisdom, it is alert, awake, wild but gentle. To be a pal of the world is, I think, the very definition of Soul, the notion of what it is to live an en-souled life. To be a pal of the world is the greatest of gifts and the greatest of privileges for it has been earned.

To be transformational is to live out of a place of compassion for ourselves and our Earth. We learn to ‘suffer with’, because we have learned to suffer and to live into and through that suffering. It is compassion that makes change, dissent, resistance, objection, evolution and revolution most effective because it

…embraces the highest form of love, which is the intimacy that does not annihilate difference. 26

To be transformational in the world is to stay intimately connected in the face of difference. When such intimacy is matched with real determination and a resolve not to be afraid-not to be caught up in fear even whilst feeling fear, then change can occur. Freedom requires courage and the prudence to know how to use that courage well and it represents the fullest expression of life. Freedom is the gift and responsibility we receive when we embrace ourselves without reservation.

As leaders and decision makers we ask ourselves, what kind of world do we want to live in? You can ask that question for yourself. Mary Oliver says that the world throws us ‘the big question’ every day: “Here you are alive. Would you like to make a comment? 27

Developmental Considerations might include:

- Optimal environments and group size for sustainable inner work.

- Art and the sacred.

- Exploration of expressive media including movement, poetry, storytelling, image making, and the use of psychological practices such as active imagination.

- Nature, art and creativity.

- Science as art: the poetry of mathematics.

2.5 Conclusions

A new model of executive education that includes and makes central the role of the transpersonal will be radical in the sense that it will require educators, practitioners and delegates to embrace new learning processes that may seem counter intuitive within current business model frameworks. It requires that we necessarily transcend the limits of current operational maps and models based as they are on assumptions that continue to insist on instructional learning models that are almost exclusively objective, reductionist and positivist in nature. Such a step change is necessary, however, if we are to cultivate self-transforming minds in future leaders.

What kind of world do we want to live in? As our perspective on life widens to take in more of the world we ask ourselves that question in more nuanced ways. Maybe, when we are connected with our man child heart, with our woman child heart we realise that we do indeed create the world into which we are always moving, moment by moment, through what we allow, what we support, what we deny, what we omit. What we create, what we pay attention to depends on the orientation and expansiveness of our consciousness — the quality of ourselves that we bring to the world both as it is and as it could be. Every decision, every act is our response to the world, be it an act of creation or destruction, large or small. In every moment our future flows into the present and we influence that process through the ways in which we direct our consciousness, our spirit, our attention.

The gift that we receive as a result of engaging in our inner work is the gift of freedom; freedom to be ourselves and freedom to be authentic actors in the world which is, in the spirit of reciprocation, the gift we give back. To become whole then is, in a very meaningful sense, to become free because we are freed from the tyranny of our own dividedness. In embracing ourselves as we are and then the world on its own terms we are given the gifts of place and ease. To live displaced and dis-eased is to suffer greatly in isolation. To have ‘place’, to live and move loose-limbed in the world is to have meaning and to fill the world with meaning. To refuse the call towards our own evolution and creativity is to suffer:

No punishment that anybody could lay on us could possibly be worse than the punishment we lay on ourselves by conspiring in our own diminishment, by living a divided life, by failing to make that fundamental decision to act and speak on the outside in ways consonant with what we know to be true on the inside.28

What does it mean to embrace the world on its own terms? From a universal perspective we experience the world as intimately, imminently alive. It is abundant with life in myriad forms. On the other side of the frontier of civilisation, through the darkness of our neuroses of separation we wander into a world that is alive, ever present and always unfolding out of itself. We cannot say it is controlled, nor is it chaos. There is an order here, a stochastic flow — random purposefulness epi-cycling without end between creative action and evolutionary response. Time and space take on new meanings. Where the ego defines itself through its capacity for thought cogito ergo sum, the universal Intelligence experiences itself as intimately connected to all there is; Tat Tvam Asi. Thou art that. Let’s leave the last word to the poets. In A Summers Day, Mary Oliver asks the question, that one day, if we are very lucky, we might all be able find a meaningful response to.

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life? 29

BIBLIOGRAPHY and NOTES

- Epoch of Transformation: An Interpersonal Leadership Model for the 21st Century–Part 1 N. Ross p2-4 2012 Integral Leadership Review, January 2012 ed.

- Pearce, Joseph Chilton. Strange Loops and Gestures of Creation. Benson, NC: Goldenstone Press, 2010

- Ibid.

- Andreasen, Anthony. Resonance-The secret of Life: Yoga and Life:( Vol 2 no 6)

- Palmer, Parker J. Leading From Within. Extract from Chapter 5 of Let your Life Speak. John Wiley & Sons 1999

- Fuhrmann,Pam. Paper entitled: Psyche, Conscious Development, and the Divine Feminine in the Modern Era 2012

- Hillman, James: Healing Fiction. Spring Publications Inc. 1994

- Jung, Carl. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Fontana Press 1995

- Baring, Ann. The Great Work: Healing the Wasteland 2005 Presentation to the Mystics and Scientists Conference

- Parker J Palmer defines Sacred as worthy of respect. Since everything is worthy of respect at some level, Palmer contends that all is sacred.

- Pearce, Joseph Chilton. Strange Loops and Gestures of Creation. Benson, NC: Goldenstone Press, 2010. Pearce offers an excellent description of the brain and early childhood development through chapters 1-4. I have offered a very simple synthesis of Pearce’s ideas.

- Snyder, Gary. The Practice of the Wild. Counterpoint 1990

- Greenfield, Susan. Soul, Brain and Mind from the book; From Soul to Self ed. James.C Crabbe. Routledge Books. 1999

- Pearce, Joseph Chilton. Strange Loops and Gestures of Creation. Benson, NC: Goldenstone Press, 2010.

- Oakeshott, Micheael. The politics of faith and the politics of scepticism. Yale University 1996.

- -19. Pearce, Joseph Chilton. Strange Loops and Gestures of Creation. Benson NC:Goldenstone Press, 2010.

20. Freud, Siegmund. Civilisation and its Discontents 1930.

21. Deloria, Vine. Spirit and Reason. Fulcrum Press 1999

22. Little Bear, Leroy. From a presentation given to the Scientific and Medical Network 2010

23. Yeats WB. Source unknown

24. Ayott, William. The Inheritance. PSAvalon Press 2011

25. Sandburg, Carl. The Wilderness Pubished in The rag and Bone Shop of the Heart edited by Robert Bly, James Hillman and

Michael Meade. Harper 1992

26. Palmer, Parker J. Leading From Within. Extract from Chapter 5 of Let your Life Speak. John Wiley & Sons 1999

27. Oliver, Mary. Long Life:Essays and other writings. De Capo Press 2004

28. Palmer, Parker J. Leading From Within. Extract from Chapter 5 of Let your Life Speak. John Wiley & Sons 1999

29. Oliver, Mary; The Summers Day. A poem.

About the Author

Nick Ross, BA, FRSA, has been a leadership trainer and personal development coach for over 20 years. Coming from a professional background in addictions therapy his work today includes delivery of extensive leadership development programs and executive coaching to global companies including Orange, ExxonMobil, Daimler-Benz, LaFarge, Fed Ex, AXA and McDonalds. Nick is a lead presenter with Olivier Mythodrama Associates where he also has responsibility for global strategic partnership development. Nick has also been involved in collaborations with Oxford Said Business School in the delivery of the BAE Delta Leadership program and with Israel Mythodrama in leadership development with AMDOCS. Nick is a consultant with the MESA Research Group and In Claritas and is on the faculty at UNC.

Nick has a longstanding interest in understanding human consciousness and its application in the development of organizations and leadership in the 21st century. Nick draws his inspiration from time spent learning from a variety of aboriginal cultures and influential individuals including Elisabeth Kubler Ross and has a strong interest and developing practice in transpersonal, and archetypal psychology inspired by the practice of individuals such as Stanislav Grof and his wife Christina, Robert Moore and James Hillman. Nick has been involved in the use of Hemi Sync technology, pioneered by Robert Monroe, for nearly 25 years and is a member of the TMI Professional Division in Virginia. Nick is a member of the Community of Inter-Being, a network founded by Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Tich Nhat Hanh, and is also a member of The Scientific and medical network. For further information about Alternative Curriculum and retreats please Email Nick at: nick@adifferentdrum.biz