Gail Hochachka

Abstract: One Sky carried out an Integral Leadership Program with the Brazil nut value chain in Bolivia and Peru, in partnership with Costco the fourth largest retailer in the US, as well as Candor, one of his main buyers, along with the Canadian nonprofit organization Integral Without Borders Institute. As an overall goal, the program sought to foster a personal, collective and systemic transformation of the Brazil nut value chain through an emergent design, based on integral principles. It included five retreats over 18 months, in-depth self-development as a leader, extensive learning about the social and environmental dimensions of the value chain, the importance of quality of the product, and effectiveness of the value chain itself. The program intended to generate the depth of relationships and trust to create a more unified vision amongst all actors and a more resilient value chain, able to exist fluidly amongst the on-going threats that global issues pose for sustainable supply. This article discusses the design and the methodology, and then reports on the success towards this end, considering the indicators for change in all of these dimensions of transformation.

Abstract: One Sky carried out an Integral Leadership Program with the Brazil nut value chain in Bolivia and Peru, in partnership with Costco the fourth largest retailer in the US, as well as Candor, one of his main buyers, along with the Canadian nonprofit organization Integral Without Borders Institute. As an overall goal, the program sought to foster a personal, collective and systemic transformation of the Brazil nut value chain through an emergent design, based on integral principles. It included five retreats over 18 months, in-depth self-development as a leader, extensive learning about the social and environmental dimensions of the value chain, the importance of quality of the product, and effectiveness of the value chain itself. The program intended to generate the depth of relationships and trust to create a more unified vision amongst all actors and a more resilient value chain, able to exist fluidly amongst the on-going threats that global issues pose for sustainable supply. This article discusses the design and the methodology, and then reports on the success towards this end, considering the indicators for change in all of these dimensions of transformation.

Introduction

The Canadian nonprofit organization, One Sky, in partnership with Integral Without Borders, took the integral leadership curriculum from work in West Africa and adjusted and aligned it to be used in the private sector in Peru and Bolivia. Our private sector partners were Costco, the fourth largest North American retailer who is generally known for its moral business practices both inside its own organization as well as with the communities and regions it works in, and one of its main buyers Candor, an innovative company who holds a simple, fascinating and transformative principle to “honour source” in their global business practices. These companies are keenly exploring market-based approaches to address the underlying issues of poverty and malnutrition, in the communities that source these products.

The One Sky core team included facilitators Michael Simpson (Canadian), Gail Hochachka (Canadian) and César Morán-Cahusac (Peruvian), then Integral Coaches Alex Streubel (Colombia) and Márcia Kodama (Brazil), and Big Mind facilitator Santiago Jimenez (Colombia).

It is important to point out here at the outset of this article that One Sky has 12-year history working in global sustainability in the nonprofit sector, mainly in the Global South but also in Canada, almost exclusively with partner organizations with overt social change missions. It was unusual and unique for our team to engage with private sector, and such large corporations at that. We came into the process not without a critical inquiry, and a critical self-inquiry, doing constant check-ins with each other on how this was going, on whether we were retaining our own change mission in the midst of this private sector engagement, as well as on how we were holding ‘beginners mind’ to open to the potential of this synergy. The critiques of big business in a context of sustainability were never far from our minds—such as, corporate agendas with goals for limitless growth on a planet with finite resources—and yet we attempted to hold a transcend-and-include space where those perspectives could co-exist alongside the other potentials present in this initiative. We were also genuinely curious and open to exploring how the global marketplace might actually form its own evolutionary pathways beyond itself, and were appreciative and mindful of the power that private sector could bring to bear on a large-scale global change.

We began with 28 Peruvians and Bolivians, who come from every point in the value chain: local harvesters, leaders of indigenous peoples’ associations, landowners with large Brazil nut concessions, people involved in shelling, buyers and sellers, and some individuals from the public sector (government offices who regulate various aspects of the Brazil nut trade) and from the nonprofit sector (NGOs in the region who support Brazil nut harvest due to the fact that it can both serve conservation and community development objectives). This atrophied down to a core 15 people, who represented the most important groups and actors within the value chain, and who were authentically on board this type of process.

The private sector players in this project use the term “value chain” in an unique and innovative way, which is important to point out from the start. Described by Sheri Flies of Costco (personal communication, 2014):

A value chain is where everyone (1) provides value and in turn (2) receives value. We look at deeper questions: if someone is not providing value, we give them the chance to do so and if they cannot, they are asked to leave—thus, value chain: if you don’t provide value you don’t belong. This eliminates useless middleman that actually don’t do anything. With the streamlining of the chain, efficiency and cost savings ensue. With the cost savings, we can then look at the second part of the definition. We use the cost savings to give back to the communities, improve value/quality and infrastructure, while also lowering costs to the consumer. Everyone needs to receive a fair return, including the consumer. This is how we shift systems. A fair return is defined differently by each segment of the chain and is fluid based upon the needs at the time. These are organic and constantly evolving systems. I point out this definition because not all retailers share this view and/or definition and I think it crucial to point that out up front, especially if we want to replicate it in the private sector.

Moving from that definition, with a constellation of champions who were in the right place and the right time, drawing on integral methodologies used elsewhere, and including an advisory that included some of the brightest minds we know, One Sky with Costco and Candor carried out this 18-month integral leadership program. It became, essentially, a transformation personally as well as within the system of the value chain itself.

In brief executive summary, at a personal level most participants:

- Gained new perspective and greater ecological and social awareness.

- Were more able to connect their own work in the value chain with the larger global context of business.

- Gained greater self-empowerment and the ability to voice their opinions and insights about the value chain—from the local harvesters through to the buyers in Lima.

- Experienced a shift in their sense of ownership, where they went from being a “cog in a machine” to being a leader for a “greater whole”.

- Experienced a positive change in their capacity as a leader.

- Improved their communication skills and ability to resolve conflicts.

- Had an opportunity to practice and gained new confidence in public speaking, planning and visioning skills in a safe context.

- Reported a general sense of having improved as a person.

Our evaluation also assessed that as a value chain (in terms of a culture of actors as well as a system of business):

- There is now greater trust and transparency, which has a direct connection with how fluidly and effectively the value chain operates.

- There is now greater capacity to resolve conflicts as they inevitably arise, with a stronger sense of shared identity and unified vision, all of which corresponds with a cultural shift from being like, “disconnected computers” toward being like, “an Amazonian rainforest in harmony.”

- There is collective agreement that the value chain functions well now, but there is still room to improve, and that their largest challenges may lie ahead.

- The leadership program greatly assisted to strengthen the value chain from its inception.

- The quantity of containers went from 1 to 14, and the time it took to get product to market was reduced.

- The process for negotiating price has stabilized and moved out of the speculative model that is otherwise used in Peru.

- The model used in this leadership training is one worth replicating in other value chains, particularly those that are in a startup phase.

In this article, we first share the design of this program, with some highlights from the curriculum, and then track the all-quadrant results of this value chain transformation that were identified in the concluding integral evaluation of the project. Also, throughout this document in the side boxes, we have included stories of personal transformation.

The Design

Where does design actually begin, in a process like this one? Is it in the transcendent intention held to uplift consciousness at key leverage points across the planet, or at points particularly available and open to transformation? Did it first start in conversations between leaders in the private and non-profit sector some four years ago, in a completely different country to where the program actually took place? Did it start when we put our minds together and put pen to paper on how this could actually roll out?

Perhaps all of these. Insight is accessed in the deepest recesses of the soul. It then cascades into greater densities of ideas, planning and coordination. Before it finally crystallizes into form, with participants coming from all parts of the value chain, from the rainforest villages to the ports in Lima and La Paz, and facilitators beginning the journey of an integral leadership program. Indeed, all points along this trajectory reach from the Absolute to the relative; this movement of Spirit-in-action contributed to seeding the transformation not only of a value chain and the actors within it, but also of an entire global marketplace.

We sought to use an Integral Approach to lay the emergent conditions for transformation within a value chain, primarily working with actors at every point of the value chain. On the one hand, we were experimenting with the theoretical rigor of Integral Theory that suggests when a comprehensive slice of reality is engaged in a coherent way, results will be profound and lasting. We were testing to see if this inherent intelligence of the theory actually manifests as such in practice. On the other hand, we were replicating the deep structure of previous integral leadership and capacity development we had carried out within the civil society sector elsewhere (Nigeria, 2009-2011 and Peru, 2007-2009).

The central axis of this entire endeavor is that of transformation. Call it a meta-objective, or an overarching goal, or a central axis, point of being: we were aiming to get individual and social holons to transform. From there, the entire methodology is geared toward that transformation (and some translation). Our design was oriented to create the conditions for this transformative flow that goes from ego-centric to socio-centric to worldcentric. We were open to “anything” arising from that flow, and thus had few concrete objectives articulated at the outset. By “anything” we were referring to anything that was translative (health achieved within a given level of consciousness) or transformative (growth to later levels); we were not referring to the emergence of regressive states or stages, where higher perspectives broke down completely into competing egocentric blocks.

So we held this broad, wide, general template of transformation—a frame for virtually ANY sort of transformation in individuals and collectives and their links—and were working with both changes in structures (egocentric to sociocentric to worldcentric), and states (both meditative and using Scharmer’s natural states in the U-Process), guided by an all-quadrant model, and “throwing all of them together for a ‘god knows what’ outcome—as long as it’s actually transformative.” (Wilber, K. personal communication 2013).

Though this may come across ad hoc to some, it is worth taking a moment to note some advantages of developing a technology like this. First of all, it truly honors the inherent, natural evolutionary intelligence in a system. That is, we may not be the ones to actually say to where or to what a system should transform; that is not for external actors to impose but rather for the system itself to give rise to. By sheering away our own preferences of where or how this transformation should go we actually honor, in a non-attached way, where it is actually inclined to go. There is wisdom and great respect felt in such non-attached action. Also, there is another pragmatic advantage of such an approach:

In any situation where we would like to see an improvement in any number of parameters—but perhaps we don’t fully understand all the variables involved, and so we can’t set out detailed goals and mission statements—we could apply this ‘generalized transformation technology’ which, in working with a deliberately broad number of parameters and opening the system at large, its links, and its individuals all to undergo transformation, the technology itself would seek out the areas of least resistance to transformation and undergo transformation at those points. The better we understood a system and all its variables, the more specifically goal-directed we could be from the start, and the less we understood the system, the more we could apply this ‘open-system transformation’ model. (Wilber, K., personal communication, 2013)

In this case, we didn’t have detailed knowledge of the context and this was the first type of collaboration between the groups mentioned, and thus we opted to use this open-system transformation model. In this, we construed the value chain as a holarchy of greater and greater depth, developing leadership capacity at each fulcrum point of that holarchy, and activating the emergent nature of transformation towards greater perspectivism.

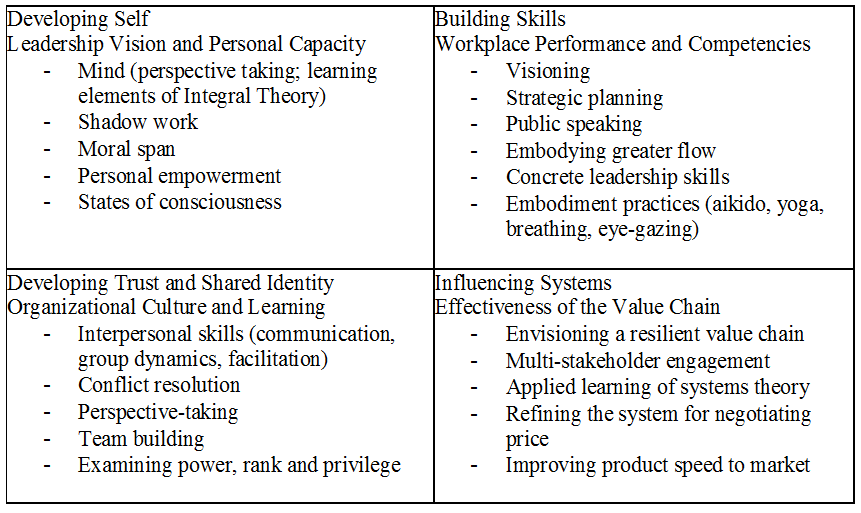

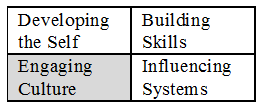

Within this meta-frame, there were four central modules of this program, with the types of themes covered (examples depicted in the diagram below).

1. Developing Self—Leadership Vision and Personal Capacity

2. Building Skills—Workplace Performance and Competencies

3. Developing Trust and Shared Identity—Organizational Culture

4. Influencing Systems—Effectiveness of the Value Chain

Outcomes and Criteria

Under our open-system transformation model, as we came to understand the many variables at play more fully, we also articulated associated outcomes for each quadrant. These are depicted below with the criteria used for each.

Methodology

Retreats

The training took place in Puerto Maldonado, Peru and Cobija, Bolivia in the Amazon rainforest over 18 months beginning in April 2013-October 2014. Participants took part in 4.5-day training sessions and participated in ongoing learning and individual and group coaching in between sessions.

The workshops and learning activities held at retreat intensives held the following design principles.

- Iterative learning as part of an action-inquiry: Moving from theory to practice to application to reflection to theory.

- Developmental: Aligning with the current level and creating conditions for emergence.

- Participatory yet lead: Striking a balance between enabling participants to be teachers/contributors in the program, while also holding a role as leader of the overall meta-perspective.

- Engaging learning in multiple-perspectives: Employing and inviting first-person, second-person, and third-person perspectives in the learning approach and content. So, we included didactic learning (lectures, presentations), dialogue (small group work, large group discussion), and experiential (reflection, self-inquiry, embodiment exercises).

- Creating space for personal expression within the group: Facilitating trust, allowing self-expression and self-reflection, giving opportunities for people to practice speaking publically, giving voice to everyone, bringing group awareness to the individual.

- Designing retreat intensives such that every aspect is about learning and can be replicated: Using the holonic-design of the retreats as a learning opportunity, so that participants can replicate this design with their home organizations.

- Consistently making the connection between personal practice and professional work. Using rituals, visualizations, story-telling, embodiment practices, journaling, shadow work, and meditation as well as Big Mind process.

- Holding, articulating, and co-creating meta-vision: Holding the “banks of the developmental stream” through co-creating towards transformation.

- Orienting this work as part of a larger integral social change mission: Working with the understanding and commitment that this is not a one-off project, but part of a suite of interventions that support a larger sustainable, integral social change.

Integral CoachingTM

Integral CoachingTM is a useful way to engage people’s individual change processes. Unlike a client who seeks out integral coaching usually when they sense they are at a cross-roads in their life, or a fulcrum point in their own development, the participants here may or may not be at such a point. Which is to say that the integral coaching may be addressing a translation (change within a level) or a true transformation between levels. In the former cases, this coaching may not have too noticeable an impact but in the latter case, it can support a vast shift, personally or professionally. In either case, participants are given metaphors to illustrate their ‘current way of being’ and ‘new way of being’ along with practices to move them between these. We have found that this assists at a personal level the transformative process we hold collectively. In most cases the personal coaching program reflects aspects we’ve already covered in the group, and reinforces it.

U Process

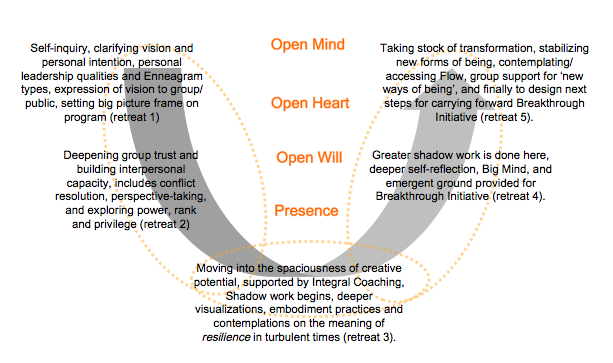

The retreat intensives followed the U Process of Scharmer (Scharmer, 2014). Retreat One brings people into the room, facilitates them to first locate themselves in this group, in their professions, in their largest vision for their life. In other words, it really begins with a self-centric sphere: who are we, what are we doing and what are we here for? Usually this also facilitates the beginning of group trust, as the group gels through this personal dimension within their shared professional dimension.

Retreat Two brings the group deeper into that group trust, which is specifically important for a value chain where usually one actor only interacts with another based on a business transaction. Under normal conditions, these actors don’t get to know each other to the extent that they actually did in this program. Retreat Two covers some of the key components of a healthy interpersonal domain, such as conflict resolution, understanding perspectives (levels of consciousness), and exploring power, rank and privilege.

Retreat Three moves the group into Presence, into the spaciousness of creative potential, or the ‘bottom of the U’, which is supported by Integral CoachingTM that runs concurrent to the retreat sessions. Shadow work begins in this session, as well as deeper visualizations, embodiment practices and collective contemplations on the meaning of resilience in turbulent times.

Retreat Four is where greater shadow work is done, deeper self-reflection (circling back to exercises done in Retreat One, such as personal visioning and self-expression), and the emergent ground provided for emergence. In this case, it was the Integrated Nuts movement, which arose completely from the initiative of participants as a way to articulate their shared values and principles for the Brazil nut sector in Peru and Bolivia, which sets them apart as leaders and innovators in the field. This is the first move up the other side of the U.

Retreat Five is taking stock of transformation, stabilizing new forms of being, contemplating where one is stuck and where one is flowing, sharing personal stories of change and transformation to confirm group support of these ‘new ways of being’, and finally to design next steps for carrying forward the emergent design (in this case Integrated Nuts). This is the stabilizing of the new way of being on the farther reaches up the U.

Breakthrough Initiatives

Leadership work cannot occur in a vacuum. Effects from working individually have to find a way to land in the real world of people’s work. The substrate for a breakthrough initiative was the Brazil nut value chain itself.

This notion of breakthrough initiative comes from the United Nation’s Development Program (UNDP) work in leadership training in the HIV/AIDS field:

A breakthrough happens when one achieves something that was previously seen as impossible for the community one serves. During the Leadership Development Programme, participants in small teams form breakthrough initiatives that are laboratories for trying out new ideas and methodologies, and vehicles for producing measurable results. Breakthrough initiatives must fulfill certain criteria including: leverage, visibility and measurability, producing near-term results, going beyond ‘business as usual’ (e.g., reflecting velocity, productivity, innovation, effectiveness, participation, impact, efficiency). (Sharma, M.; Gueye, M; Reid, S; Sarr, C., 2005)

In this project, the creation of Integrated Nuts was the groups’ breakthrough initiative. It arose in Retreat Four and has since become a way for the value chain to identify the needs in communities, processing facilities, or in the environment that should be awarded funds. Increasingly buyers are paying a ‘premium’ on a product, to ensure they are paying the true cost of a product. That ‘true cost’ must consider the social and environmental wellbeing for that product to exist and enter the supply chain. This contributes to a sustainable supply chain, as well as greater sustainability in the communities and ecosystems where these products come from. Integrated Nuts is positioned at this intersection, to assist in directing funds from purchasing ‘true cost’ to the more pressing needs in communities and ecosystems.

Evaluation

Projects that deal with complex issues require a truly non-linear and emergent project design that engages both the interior and exterior dimensions of change. Evaluation of such projects can be tricky as their complexity evades the usual problem-solving techniques. We can’t use the linear formal evaluations effectively in these cases. Instead, we have to include methods from all four quadrants used in integral approaches and also track changes across a trajectory of innovation that develops.

To evaluate this project, we sought an evaluation process that could capture the full transformation that occurred in this program, which is what we share here in this article. Our Integral Evaluation included personal interviews with the participants to assess their own personal change stories, collective assessments during the retreat, and a survey at the end. As well it included direct-observation (both at the leadership retreats and in the weeks following) and, we were also assessing for transformation in the individuals, the collective, and in the “innovation” itself (this being the emergent outcome of the leadership program on the Brazil nut trade in these two countries).

Data Sources

Developing the Self—Leadership Vision and Personal Capacity

Change in Perspective and Awareness

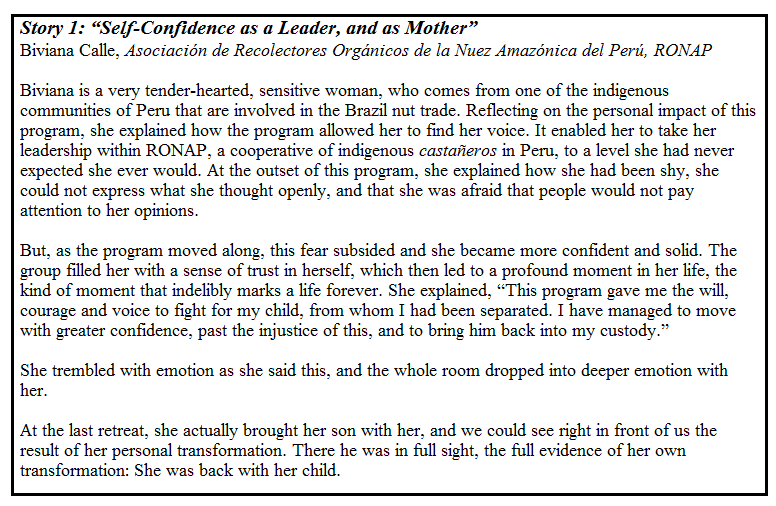

Participants experienced a change in self-awareness. For some, this had a direct impact on their professional lives (see Story 2 on Kathleen Sharkey of Caro Nut below). For others, this occurred in their personal lives: over the course of this program, unhealthy relationships have split up, others have taken their commitments to deeper levels with marriages and pregnancies, others have reunited with estranged family members (see Story 1 box below on Biviana Calle of RONAP (Asociación de Recolectores Orgánicos de la Nuez Amazónica del Perú), Story 3 box Billy Echeverria of Rainforest Action Network, and Story 4 on Miguel Zamalloa of RONAP). Simply put, lives have changed. Here, we asked people to specifically speak to how their awareness of environmental and social issues has changed over this program.

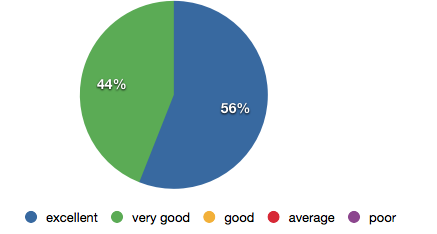

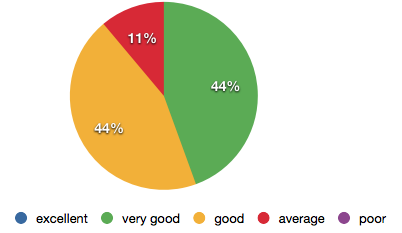

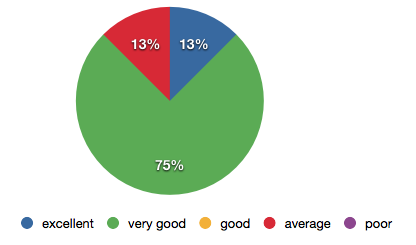

Participants spoke of gaining new environmental and social awareness. When asked how conscious or aware they were of social and ecological issues upon completion of the program, over 89% of respondents ranked their awareness as “very good” to “excellent.”(For all diagrams, n=10, which is a sample approximately 75% of the graduating group.)

One young woman from an indigenous community spoke about how she used to watch her mother gather the cans and bottles to recycle them but didn’t really understand what she was doing. Now, she is able to connect her mother’s recycling efforts with the larger picture about how to protect the Brazil nut trees and surrounding forests. (Biviana Calle, RONAP)

For some, this shift in awareness that occurred collectively served to support an individual’s existing environmental ethic. Said Miguel of RONAP, “This program has strengthened my environmental awareness, although this has always been important to me. It strengthened the awareness I have always had, I feel supported and vindicated by this, I am not alone. Now I know I am not alone.”

Taddy Villaverde of Vitalianos spoke most eloquently about this shift in awareness, saying:

“These workshops have been a strong process that has enabled us to see and understand the importance of the Brazil nut tree. Through this program I have realized that every single nut goes through an extensive process; each nut is filled with emotion for me, because behind each nut there are so many people, there are the communities and there are the rainforests. Understanding this has completely changed my perspective.” (Taddy Villaverde, Vitalianos)

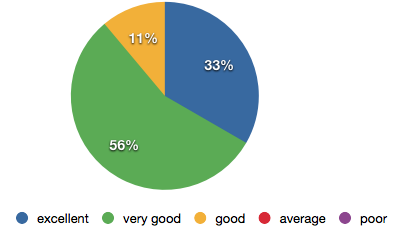

We sought to provide a global context in which to understand the Brazil nut value chain. Upon completion of the program, 88% of survey respondents said that their ability to connect their own work within the value chain to a larger, global understanding ranked at “very good” to “excellent.”

Diagram 2: The extent to which participants are able to see their work connected to the larger, global context.

Carolina Jara of Candor summarized this shift in perspective very well, “Changes have been established, and we have planted the seeds for the foundation of what we want with this. We have the opportunity here to manifest a value chain that not only creates economic value but also has a positive impact in social and environmental issues. They all have realized this.”

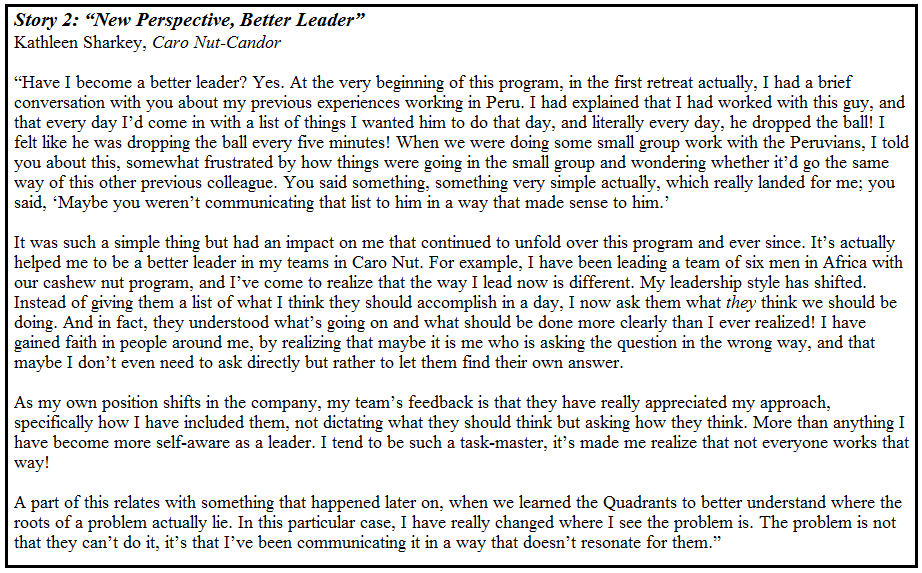

Finally, Kathleen Sharkey reflected on the changes in social awareness that were a result of this program, specifically in terms of how her company could affect their community wellbeing better, simply by shifting their perspective slightly. She explained:

“In regards to where they store the nuts… At the outset, we built a warehouse on a vacant piece of land. But I’ve come to see that it’s in an awkward place, it made more sense to take it to a different warehouse that was easier to get to. I went from thinking, ‘find a piece of vacant land and build a storehouse’ to ‘how would this best work for the community to access and use?’ My perspective shifted.”

Empowerment

Participants also demonstrated an increase in empowerment which, on the one hand is central to entrepreneurial attitudes, on the other hand, it can be particularly tricky in business relationships where power is held unequally. Often, the person with less power ends up remaining silent, even when they have invaluable wisdom to share on a particular point. This was true of certain participants, where through the program, they gained access to their personal power and their voice, and thus were able to add value into the business and into the value chain. “I feel that I am more empowered. I feel people listen to me, before I did not know how to express myself.” (Viviana de Olarte, Candor)

Empowerment is particularly important for the indigenous people involved in the Brazil nut trade. The intention sought by Costco to identify and pay fair return provided a degree of empowerment for these people. Said Herman Bascope of the Takana community, “I am empowered now, because when the community asks ‘what have you done, are there any changes, any new perspectives?’ I can answer confidently now that we have a ‘plus’ for the communities and we have considered how we can meet the community’s needs for basic sanitation.”

A Sense of Ownership

We noticed how, prior to the leadership program, “the value chain” was experienced as something people were subject to or immersed in, but after the program, the value chain became comprehensible as something they could actually work on, innovate, and excel at, as well as be intimately part of. Being able to “take it as object”—that is, to lift one’s head from the daily grind of one’s small piece of the larger whole and actually perceive that whole as well as one’s own crucial part in it—is a shift in awareness. And, that shift that seemed to co-arise with greater ownership. From other work elsewhere, we can attest that an increase in ownership is a critical ingredient for sustainability of results.

“Thanks to the workshops and what each link offers, one feels the value chain as a whole and we have the sense that it belongs to us.” (Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP)

Before the workshops I had no idea what the value chain was and moreover I only saw myself as a castañero. I can now explain what it is, I can see now that others view me as an important person, and I am more informed about the value chain. I have a value and a position in the value chain; we are the first in the chain because we are the collectors of the nuts. (Herman Bascope, Takana)

Building Skills—Workplace Performance and Core Competencies

Leadership Capacity

We asked participants directly if they thought they had become a better leader through this program, with evidence as to why they thought that.

Miguel Zamalloa, the President of RONAP explained, “Yes, I am now a better leader. These two years of work has enabled me to have a closer relationship with the RONAP’s partners and they now see how my ideas are beneficial. Moreover, this year I was reelected unanimously and they are going to give me an economic recognition for my work.”

Taddy Villaverde of Vitalianos explained, “It allowed me to see in what way we were failing in my company. Before, our presence [as Founders and Directors] was needed, now our people make their own decisions and they do it well.” She and her colleague Michel Llanos went on to explain how the shift in their own self-awareness and their own actions within the company changed over the course of the program and the impressive impact it had on the rest of the company.

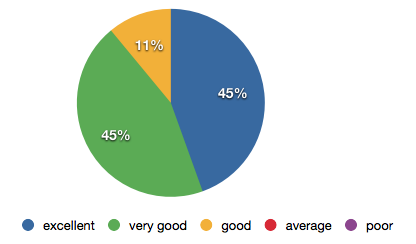

Over 75% of survey respondents rated the value chain as having “very good” or “excellent” leadership capacity upon completion of the program. Carolina Jara of Candor said, “There used to be only one leader, now everyone is a leader.”

However, this process of becoming a new leader, really transforming personally, can be a longer process than just a year and a half. Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP, particularly spoke about how to really, genuinely change patterns inside oneself that have taken 30 or 40 years to develop may take more course corrections, support and feedback than this 18-month program itself provides. He and others have suggested an annual meeting to check in with each other, do any course-corrections that are necessary, and proceed further into and beyond the transformation of the value chain. Carolina Jara proposed to have an IN gathering in September/October 2015.

Communication Skills

Communication improved in the value chain, moving from barely any communication at all to “good” to “very good” according to the survey.

What changed in the value chain was communication, in the beginning we did not know how to say what we thought, how to solve conflicts. We have learned how to say what we feel…I feel we are now more informed, with a more fluid communication. (Taddy Villaverde, Vitalianos)

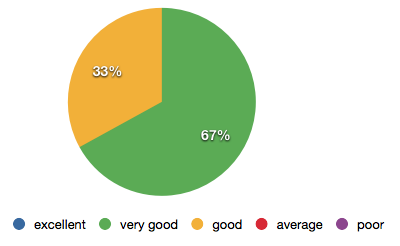

67% of survey respondents rated communication in the value chain at the end of the program as “very good” with the remaining 33% rating it as “good.” Given that all the actors in the value chain were present, some of whom have more power than others, a “very good” ability to communicate indicates a success on this front.

Diagram 4: Survey respondents regarding the communication in the value chain upon completion of the leadership program.

Kathleen Sharkey of Caro Nut explained, “It’s not always about the product, it is also important whether you like the person behind it all that you have to have conversations with throughout a year. There has been an improvement in communication and now there is a stronger relationship between who Caro Nut is and what we are doing there.”

Visioning, Planning, Public-speaking

We took videos of individuals sharing their personal vision in a three-minute speech at retreat 1 and again in retreat 4, providing participants a way to gauge their own ability to vision and communicate that vision to others. It was impressive to see the degree of change in these videos. All of the participants improved in their abilities, while some of the natural public speakers really excelled.

Michel Llanos of Vitalianos said, “I learned how I am as a person. With [the Integral Coaching] I learned to move forward. To understand where is it that I want to go, to have more order. I have allowed our company to flow; this has allowed our company to improve… Our company moves forward by itself now. These workshops have helped to orient and train us, and through it, we have become leaders. This is a concrete result.”

Self-Improvement

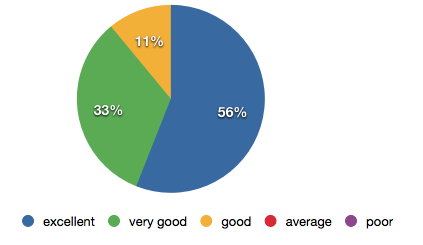

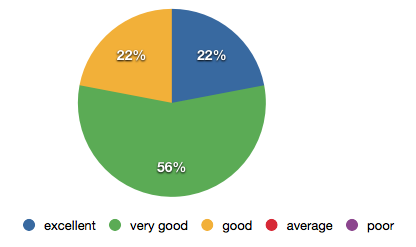

When participants were asked to what extent the program helped them to improve as a person, 56% ranked it as “excellent” and the remaining 44% ranked it as “very good.” This self-improvement was certainly a key success of the program, as many of the other quotes and stories from participants attest to throughout this document. The principle behind this focus is that self-improvement corresponds with improved innovation and initiative, which in turn supports good business.

Developing Trust and Shared Identity—Organizational Culture and Learning

Trust and Transparency

The central axis of a value chain is trust. Biviana Calle, Secretary of RONAP explained, “I think we as a value chain have improved in trust and transparency, and we have demonstrated that since the second workshop.”

This trust affected how people negotiated price (see more below in Stabilized Price) and how they understand the process of the value chain itself, all of which contributes directly to the ease and speed with which business can take place.

Biviana Calle of RONAP described the experience of this greater trust and transparency, “Previously, I did not know anything about the value chain; [our previous buyer] never told us about it and did not explain its processes. They only showed us that they sold the product. With Candor there is a big change: we do know how the value chain works and we can now explain it to others.”

Conflict Resolution (the Ability to Take Others’ Perspectives)

Most of the participants spoke about new capacity to take others’ perspectives, and many noted the important role that has played in improving interpersonal skills and resolving conflict. Most spoke of a positive impact in regards to perspective-taking in the context of relationships in both a personal and professional sense.

We observed the impact of this ability to take the perspective of another in the final retreat when two potential conflicts arose: one in which RONAP owed a debt to Candor and another in which the Takana community had obtained a loan from Candor to get a boat but then used the money for something else. These types of conflicts often arise in the flow of business involving local producer communities and buyers. The question is more around how they will be solved, and what attitudes people will take in solving them.

In the above cases, the president of RONAP literally wept in a group process, so fully did he recognize the error of not paying back the debt to Candor and in social recognition of the need to follow through on that as soon as possible. And, the representative from Takana spoke emotionally about how he hadn’t known of the situation of Candor financing a boat which was never actually purchased by the Takana member in question, and said that he’d do his very best to make that right.

Carolina Jara of Candor explained, “Sometimes people do not want to change things, but there has been a transformation in the way we act and think. There were moments of internal conflicts but I see those are needed for the value chain to grow. Through this process, everybody has shown honesty and a lot of open-mindedness. People are not in a defensive mode and there is more participation.”

Kathleen Sharkey also commented, “The question is how we’ll meet the challenges as they arise, not that they won’t arise at all. I think there were results obtained in greater capacity in conflict resolution: how to face the issue and understand it.” She went on to explain how now, as an entire value chain, people have a better understanding of where an issue may actually lie in a conflict, and that when a conflict arises, the group is now more open to asking, “Hey, is that really the issue here?” Kathleen sees this as a concrete result that was obtained over the course of this program.

From these examples, we can see that by placing people a) in a program altogether where the trust amongst each person increased and the social contracts became clearer and more personal, and b) in providing conflict resolution training over the five retreats, we have seen a substantial increase in the capacity to resolve conflict. And hopefully over time, the capacity will continue to build to avoid such conflicts in the future with shared social collateral.

Shared Identity and Unified Vision

There is a coherent sense of We in the group, and a lot of interpersonal support for one another. People spoke highly of each other, and were supportive and challenging in a style particular to a group that knows each other well. 38% of survey respondents said the sense of shared identity was “excellent” with another 38% saying it was “very good” and 25% seeing it as “good.”

Diagram 7: Survey respondents rating the sense of shared identity of the value chain after the program.

According to the interviewees, over the course of the five retreats, this sense of shared identity strengthened:

“We are a group, in fact we have a name now, we are solid, and we will grow by incorporating new members.” (Taddy Villaverde, Vitalianos)

It helped us to value every part of the value chain. In my case I thought it was only a product that was harvested, but, I have realized that there are so many things involved in this natural product: nature, people, different cultures, communities. (Michel Llanos, Vitalianos)

We asked people how they felt as a link in the larger value chain, upon completion of the leadership program. Said Miguel of RONAP, “I feel much better. I see we (as RONAP) are an important link in the chain. If I leave, or if we leave, that important piece would be missing. I have offered my collaboration and I am now more connected with the Candor team (Carolina Jara, Viviana de Olarte) and the Bolivians, all thanks to these workshops.”

New Culture as a Value Chain

Culturally, the value chain has transformed: “we are now Integrated Nuts (IN) and that can become our culture, a way to identify us.” (Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP) This shared identity does indeed affect how the whole operates with greater accountability and resilience:

You are actually part of the whole, not just a link in a chain, and so this gives me a sense of connection, beyond dependence, as well as a way to trust that connection. Where if one link in the chain is cheating another, we are still connected to the Company and to each other to continue. (Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP).

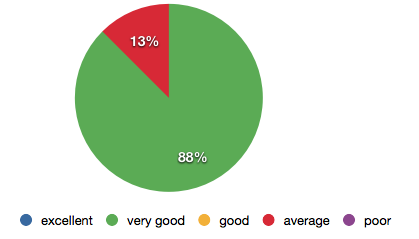

With the integral coach, the group identified ‘metaphors’ to track its own change process, including a “current way of being” and a “new way of being”. The current way of being metaphor was “Disconnected Computers” and the new way of being metaphor was “A Restored Amazonian Rainforest in Harmony”. Over 88% of survey respondents rated the value chain as “very good” in its progress towards “A Restored Amazonian Rainforest in Harmony” with the remaining 13% rated it as average.

Diagram 8: The value chain in its process from the metaphor of “Disconnected Computers” to “A Restored Amazonian Rainforest in Harmony.”

Influencing Systems—Effectiveness of the Value Chain

Value Chain Functioning

Most survey respondents ranked the value chain as “good” to “very good” in terms of how it was working, leaving room for improvement.

At the same time, most agreed that it has improved in how it works now as compared to before. Viviana de Olarte, Secretary of RONAP said, “It feels like the value chain is just starting to function, it’s finally moving! At the very beginning it was rusty, but we are now on our way!”

Said Carolina Jara, “In the beginning it was chaos, now [after the program], I find the value chain has greater order. Everybody is connected and the value chain in [Integrated Nuts] IN, we all help each other. It is a very unique value chain.”

This question on how the value chain operated previously compared to now was somewhat unclear on the survey and so those results are a bit garbled. Regardless, the take-away in both the surveys and interviews is that, while the value chain is working well, there is more than can be improved for it to rank at “excellent.”

At the same time, when asked to what degree the leadership program served to strengthen the value chain, a remarkable 90% of survey respondents rated it as “very good” to “excellent.”

Some participants explained that, although they have come a long way, the real test lies ahead; their biggest challenge is yet to come. “How did I feel about the results we’ve obtained so far? Very well. But we have a far bigger challenge in front of us.” (Viviana de Olarte, Candor). Our sense is that that this is an accurate assessment: it is easy to feel you are a group, with shared trust and identity when you are meeting every three months in a facilitated program. It is far harder to continue this group identity and flow of operations when you are not held in that facilitated process.

Quantity and Speed to Market

In terms of sheer quantity, the value chain went from selling two containers to 14 containers in a single year. Carolina Jara of Candor explained how the goal reached to date is good,

“But we can get more; our goal for 2015 is between 20 and 25 containers. And, to this with the principles of having full traceability and with a social and environmental impact is the value we add.”

Within the first year of the leadership program, Gerard Jara of Candor commented on how the product had indeed moved to market more quickly than he would have expected. Tracking this across the year, we too discovered this to be the case. It seems that the group trust that deepened amongst the actors in the chain supported the speed at which product moved.

Kathleen Sharkey, of Caro Nut, agreed that product had gone to market more quickly, but mused on why that might be the case. “I think this was due to the logistics of getting from A to B. It could have been due to greater trust and a more unified group of actors in the value chain.” She later explained how, over 18 months, any inconsistencies in terms of how an actor was showing up became apparent, so this program naturally uncovered the red flags and weeded out any player that wasn’t coming in good faith or couldn’t find a way to fit with the overall whole. This clarifying of the value chain may itself have been a reason for product moving more quickly to market.

Stabilizing Price

Assisting to stabilize or raise the commodity price for Brazil nuts is a tricky terrain, since in Peru and Bolivia there is much speculation in terms of how price is set. This becomes a game of chance: some years the producers win, but often they lose. Carolina Jara of Candor mentioned how it often costs more for a Brazil nut harvester to get the nuts out than they actually make selling the nuts on the market. Costco’s manner of working, in this regard, bodes well over the long term, as they buy at ‘true cost’ with a ‘plus’ (directing proceeds back into the communities and ecosystems).

The biggest hurdle here will be shifting the culture of working with price in a speculative way. Over the long term, Costco’s way of setting price will win out. On the short term, however, depending which way the overall price goes, harvesters may have to forego a larger, short-term speculative win to take the consistent, stable price offered by Costco.

Nevertheless, there have been gains already in this area. Kathleen remarked, “There is much less speculation surrounding price; we [Candor/Caro Nut/ Costco] have been consistent with our message overall. It has been a huge benefit over the last 18 months to have this consistent message, as it facilitates trust.”

When asked whether they had a changed sense of how price was established or negotiated, participants replied, “Yes. You see, what happens in Peru is very speculative and now I understand why [Candor] requires that any discussion on Price must be transparent.” (Viviana de Olarte, Candor). “It is definitely helpful the way that Candor works with price, because we now know what the price is [i.e. it’s no longer speculative], what the profit percentage is, and we know we can negotiate the price of our product in this process. It’s great to know the market and know that you can negotiate with it.” (Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP)

A Model Worth Repeating

All participants interviewed repeatedly said that this Integral Leadership Program was worth investing in and could be replicated in other value chains elsewhere. “Yes, it is worth repeating in other value chains. We have achieved so much!” (Viviana de Olarte, Candor)

“Definitively, yes, I see great potential for this in other value chains. This value chain is totally different, as we’ve all said… it’s a totally different value chain now… At the beginning, one could not express what one actually was! This process has been to recognize the good and the bad in yourself. These workshops support you so you can become stronger and in doing so you can cause a positive impact not only for yourself but also for others. Somehow in this program you facilitators were able to draw out the potential that even a person him or herself doesn’t know he or she has.” (Miguel Zamalloa, RONAP)

“This has been an awesome program for me. I didn’t even know what a value chain was before this, and now this makes sense and this is our work.” (Herman Bascope, Takana)

The One Sky team has been musing on how the right combination of conditions can create the possibilities for something innovative to emerge. We call this, “emergent ground.” Our test for this was the emergence of Integrated Nuts (IN). IN was not an initiative sparked by One Sky and truly arose on its own terms, from within the intelligence of the value chain itself. In fact, this occurred on Retreat Four and took us by surprise to some extent! IN exists to hold a meta-frame for the values and principles by which the Brazil nut value chain in Peru and Bolivia would like to operate, giving a larger goal to which they can direct their efforts. It may become an organizing body to make decisions on where and how to invest in greater resilience in communities and ecosystems involved in the Brazil nut trade.

Conclusion

In conclusion, One Sky sees a very positive opportunity to replicate this integral leadership program as a transformative process to shift a value chain from one that is shaky, disconnected, and distrustful to one that is cohesive, fluid and based on trust. In fact, a value chain then becomes a trust chain.

This trust was supported in several ways through our programming, from simply bringing people in the same room to moving through intimate processes of collaboration. Collaboration wherein they could hear each other’s voices, understand their values and what they are missing in their daily business as usual. We explicitly saw and then measured the way in which this trust resulted in a great fluidity in how the value chain functions. Although there is room to improve, the value chain today is transformed from what it originally was, and the actors within it too have changed.

It has been said that innovation and efficiencies for business often come from the staff themselves. But accessing and releasing human potential can be a challenge, given the structure of how a value chain operates. This program managed to tap into a collective intelligence beyond any one individual, while also empowering all individuals to access their potential and voice their wisdom from their processing facilities, their offices and even from the forest floor.

There are several “lessons learned” from this that we can bring into future programming. One Sky’s ability as a team to draw an adaptive management strategy (or, on “the art of improvisation” as Carolina Jara described), which is to fine-tune our curriculum and interventions was an important part of the leadership curriculum staying in close relationship with the needs of this particular value chain. That said, we see the need to strengthen the structure, programming and timetables in such a way that we don’t lose that flexibility. Also, our use of an integral approach allowed us to work at two scales, both the personal and the collective, as well as to engage the intangible as well as tangible aspects that support a more effective value chain.

One Sky recognizes that in the case of working with the Brazil nut sector we did miss an important player, which was the government. In the case of Peru, it’s the government that slows down enormously the speed the product traverses the value chain (Carolina Jara and Viviana de Olarte, Candor). The Government is an important silent player, due to their regulation and evaluation power. They were invited to the first and second workshops but could not continue due to their diverse obligations and “social degrees of separation” from the value chain. In Bolivia this was not the case.

Other lessons learned that we will bring into any future work include:

- The importance of identifying a champion or natural leader in the country where the value chain operates. This champion becomes a point-person for many aspects of program delivery. In this case, that person was Carolina Jara.

- The need to carry out some type of social mapping to gather the right group of actors across a value chain.

- The requirement for participants’ commitment to stay with the program for its full 12- to 18-month process.

- The need to define a firm scheduling for these retreats in order to maintain momentum and reach a driving force that could lead to better results in future value chains.

- The need to do this with other buyers in their own companies. Gerard Jara emphasized the need for this saying, “On the buyer’s side of this, it is almost an obligation that business people understand value chains from a global, holistic, personal transformation perspective. They have to get this at a deep level too.”

- Finally, that the presence of a representative from the Costco in the last workshop gave the process a deeper meaning, as the actors in the value chain saw that this was for real, that there was a new way of doing things, with respect and valuing the real production cost. In fact, maybe for the next workshops there could be a way to consider the Costco’s voice along the process to enhance the experience of the entire sequence of workshops.

The important question for a program like this was whether it was a good business decision; do the outcomes gained actually transfer into better business practice. On this topic, Sheri Flies of Costco, explained:

When we do this work, we are developing trust within our current value chains, and my belief is that the people in these value chains will stay with us when they have options in a seller’s market due to these being limited resource commodities, providing us with high quality products and competitive fair prices. This is my business case and why this work is important.

We asked Gerard Jara of Candor, who was one of the main investors into this program, whether his investment—the price breakdown per participant—was actually worth it, as a business case. His answer took the whole conversation to a new level. He said, “If I run that math, I am not doing it for the right reasons. This was a long-term bet, as a company, on transformation itself, not driven only by business, but rather rooted in deeper beliefs.”

He went on to say:

Did this program transfer into better business? Well, we’ve increased the business this year, but it is hard to say whether we grew it thanks to the program. It has helped to solve some issues that appeared during business transactions—yes. But it is too soon to say this program is good for business per se. There have been no negatives. It has been a very good thing for the personal transformation of participants, and we could say that that in itself is good for business.

Did the program satisfy me as one of its investors? Yes it did. No regret whatsoever. I think we are a better company now, thanks to this program. This has been a complete success in that sense, and I have no doubt saying that. I make a very serene, calm claim that this has been transformative. There should be no doubt about that. But, the question remains as to exactly how this will unfold in the business over time.

Musing on how this could affect business in the future, he said,

In time it will translate into better managers, and when there is less access to limited source commodities, when there will be a fight for them on the open market, when things are scrutinized, simply put: you will be ahead of the curve.

In conclusion, through this experience, One Sky has clearly seen how this integral leadership program engaged the personal, cultural and systemic transformation of this value chain, how the emergent design provided the necessary ingredients for Integrated Nuts to be created, and how an increase of collective trust supported the value chain to become more fluid, coherent, and human. Each person seeing another to the full depth and span of his or her being, and moving into business transactions from that place, undoubtedly carries a different energy and imprint. We come away with a more embodied, real sense of the possible for global business and sustainability in the future.

References

Scharmer, O. (2014). Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges. Retrieved from https://www.presencing.com/sites/default/files/page-files/Theory_U_2pageOverview.pdf

Sharma, M.; Gueye, M; Reid, S; Sarr, C. (2005). Leadership Development Programme Implementation Guide. United Nations Development Programme

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral Spirituality: A Startlingly New Role for Religion in the Modern and Postmodern World. Boston: Shambhala.

About the Author

Gail Hochachka, B.Sc., M.A., works in international sustainable development using integral principles as a Co-Director of Integral Without Borders and as the Executive Director of One Sky-The Canadian Institute for Sustainable Living. She has pioneered the use of an Integral Approach in rainforest conservation, capacity building, leadership development, climate change adaptation, and community resilience in various countries of Latin America and Africa. She is gifted in designing large-scale projects on social transformation, bringing complex theory into heartfelt action in the world. She’s a published author including the book, Developing Sustainability, Developing the Self: An Integral Approach to International and Community Development, as well as with articles in Ecological Applications, World Futures Journal, Trialog Journal for Planning and Building in the Third World, and the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice. She currently manages projects in Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and Nepal, and she lives with her family in Canada.

www.integralwithoutborders.org gail.hochachka@integralwithoutborders.org