Sue L. T. McGregor

Sue L. T. McGregor

Higher education is one of the most important arenas in which the transdisciplinary (TD) approach should be applied (Güvenen, 2016). Fortunately, educational institutions are “evolving [so they can] answer the demand for transdisciplinary skills” (Güvenen, 2016, p. 75). In concert, “educators are recognizing the vital significance of designing a transdisciplinary curriculum” (Smyth, 2017, p. 64). Indeed, it is a growing phenomenon in higher education as evidenced by several recent initiatives (see Albright, 2016; Babadi, Varaki, Khandaghi, & Karami, 2018; Constantino, 2018; Dieleman & Juarez-Najera, 2015; Huyn, 2011; McGregor, 2017; McGregor & Volckmann, 2011; Smyth, 2017).

That being said, these initiatives tended to eschew the issue of what an educational philosophy and a rationale for a TD curriculum might look like. This paper engages with this idea presuming that more people will be inclined to attempt to design a TD curriculum if they do not have to struggle with developing a description of its educational philosophy (i.e., what counts as education, teaching and learning) and a rationale for its use in higher education. A philosophy (i.e., a set of beliefs, assumptions and principles) guides actions and behaviours. A rationale is a set of reasons for a course of action or behaviour (i.e., a logical basis for doing something) (Anderson, 2014). Both are needed to contextualize and justify any curriculum initiative, especially TD-informed efforts (Etras, 2000).

Resistance to higher education TD program offerings is common for many reasons among them misunderstandings of what it means relative to multi and interdisciplinarity, funding conflict-of-interest concerns (due to closer links with industry), funding access issues due to its nondisciplinary nature, entrenched academic cultures and the politics of change, and threats to faculty members’ job security and promotion in light of prevailing disciplinary-focused hiring and advancement criteria (Hyun, 2011; McGregor & Volckmann, 2011). Challenges to transdisciplinarity’s legitimacy and relevancy in higher education can effectively be countered with the argument that it, better than any other approach, ensures that curriculum and pedagogical and andragogical practices are capable of addressing the complex societal challenges and problems of our times (Khoo, Haapakoski, Hellstén, & Malone, 2018; Saunders, 2009).

After briefly defining the term curriculum and affirming the inherent existence of philosophy and rationale in any curriculum, the discussion turns to a short overview of the need for different learners given the pervasiveness of complex, wicked problems. This is followed by the succinct introduction of Nicolescuian transdisciplinarity, which informs this paper about TD curriculum. Then the concepts of educational philosophy and curricular rationales are examined, culminating in a respective transdisciplinary orientation for each.

Curriculum Defined

A curriculum can refer to a complete course of study that takes years to complete (e.g., a university degree or high school diploma) or to individual or a collection of courses (with modules, units and lesson plans) that last for months or weeks (Hyun, 2011). Curriculum is Latin currus, ‘a race track, a set of tasks, a running’ (Harper, 2019). It is a course of learning – a course of study that runs for a period of time. Curricula comprise a set of learning goals articulated across levels (e.g., grades, university years) that outlines the intended objectives, content and processes at particular points in time throughout a program of study (Reys, Reys, Lapan, Holliday, & Wasman, 2003).

A well-thought-out curriculum will be grounded in an explicitly-articulated philosophy and a rationale. Actually, all curricula are informed by a philosophy and rationale whether clearly articulated or not because individual curriculum planners hold certain beliefs (examined or not) about education, learning and society (Ornstein, 1991; Sowell, 2000). These beliefs are, by association, reflected in their curriculum-design decisions. “All elements of curriculum are based on philosophy” (Ornstein, 1991, p. 103). TD curricula are no exception.

Wicked Problems Need Different Learners

“Exploring and promoting the transdisciplinary approach is part of the contemporary university’s social responsibility for humanity” (Hyun, 2011, p. 12). If we want students to be a different kind of citizen, one who can assume responsibility for humanity, “they first [have] to be a different kind of learner” (Lauritzen & Jaeger, 1994, p. 581). That learning takes an especially-designed curriculum of study that facilitates collaboration among diverse actors around emergent issues impacting the human condition, often called wicked problems. These are ill-structured, multicausal and involve multiple stakeholders. What worked before will not work again because the context is different. Attempts to address them often spawn new wicked problems, with the original issue actually changing because people tried to fix it. There is no guarantee or even assumption that a solution is possible or recognizable but something has to be done (Rittel & Webber, 1973).

Wicked problems include corporate-led globalization, unsustainability, climate change, global warming, refugees and forced migration, loss of biodiversity, arable land and potable water, health inequality, poverty and insecurity, violence and terrorism, and uneven human and economic development (Clark University, 2019; McGregor, 2018). To complicate matters, these wicked problems “manifest in complex ways across diverse sectors of society” (Evans, 2015, p. 74) making them even more challenging to identify, address and solve. Disciplinary, multi and interdisciplinary curricula are no longer sufficient in and of themselves – transdisciplinarity is required (i.e., between, among and beyond all disciplines) (Nicolescu, 2005, 2014).

Nicolescuian Transdisciplinarity

This discussion of TD curriculum reflects the Nicolescuian rather than Zurich approach (see McGregor, 2015). The former views TD as a methodology – a new approach for creating knowledge grounded in four philosophical axioms (i.e., presuppositions about what counts as knowledge, reality, logic and the role of values). In brief, TD epistemology holds that knowledge is complex, in vivo (alive), embodied, emergent, and cross-fertilized. Ontology includes many Levels of Reality (inner and external to humans) that interact within the fertile space where potentialities arise and integration can occur (i.e., via the invisible unifying Hidden Third). This unification and integration involve inclusive logic that facilitates the temporary reconciliation of contradictory view points. From an axiological perspective, this boundary-crossing work embraces values accommodation and integration to create transdisciplinary values (i.e., beyond individually-held values) (McGregor, 2015, 2018; Nicolescu, 2005, 2014). The transdisciplinary learning envisioned herein derives its character from these four axioms.

The intent of Nicolescuian transdisciplinarity is to more fully understand the world through the unification of knowledge (Nicolescu, 2005, 2014). This entails creating curricula that teach students how to approach and collaboratively address profoundly complex wicked problems appreciating that each instance of this type of engagement leads to more new knowledge that bridges the gap between the academy and the rest of the world. Transcending to a new space of engaged learning, where academic disciplines interact with actors from the life world, lessens the pervasive power of disciplinary specializations and knowledge fragmentation. This in turn brings people closer to a fuller understanding of the world by perpetuating the unification of knowledge (i.e., merging disciplinary knowing with life world knowing leading to new transdisciplinary knowledge) (Evans, 2015; Jeder, 2014; McGregor, 2018; Nicolescu, 2014).

To that end, in a TD curriculum, wicked “complex problems frame learning, knowledge is unknown and uncertain, the curriculum is set in real world context, it is contested, and there are consequences for learners” (Albright, 2016, p. 530). This problem-oriented curriculum expects students to “conceptually, empirically, methodologically and collaboratively engage with and [be] open to potentially relevant domains of human knowledge” (Albright, 2016, p. 530). TD curricula ensure that students engage with others beyond the confines of disciplinary expertise (Khoo et al., 2018). This involves effective, coordinated communication; self-directed, on-demand learning; and a deep understanding of metacognitive skills and mindsets (Klein, 2008).

Metacognitive skills are the core of transdisciplinary curricula (Klein, 2008; Smyth, 2017). They pertain to each person’s awareness of their own thinking and thought processes (Metcalfe & Shimamura, 1994). Cognition (Latin cognoscere, ‘get to know’) refers to the mental acquisition of knowledge through thought, experiences and the senses (Anderson, 2014; Harper, 2019). Transdisciplinary knowledge emerges from the integration of diverse perspectives, which cannot happen unless people are open to changing their minds and mindsets (i.e., habitual ways of thinking) (McGregor, 2017, 2018).

To that end, metacognition (i.e., thinking about one’s own thinking) involves two components: knowledge of cognition and regulation of cognition (Schraw, 1998). TD learners have to be fully aware of and able to regulate their internal thought processes because they are often expected to set those aside to make room for others’. Metacognition (Greek meta, ‘beyond’) means beyond regular knowing and is the crux of transdisciplinarity (Nicolescu, 2005). Any well-developed TD curriculum will reflect this imperative in its philosophy and rationale thereby setting it apart from multi and interdisciplinarity. They concern themselves with perpetuating disciplinary-informed thinking rather than thinking from the life world, beyond disciplinary boundaries (Nicolescu, 2005; Smyth, 2017).

Educational Philosophy

Philosophy is Latin philosophia, ‘love of knowledge, pursuit of wisdom.’ It is the system a person forms for the conduct of their life (Harper, 2019). A philosophy contains ideas about what is important and serves to help people to obtain, interpret, organize and use information and access other’s knowledge while making decisions and taking actions (Boggs, 1981). A curriculum philosophy sets out the goals and aims of the curriculum. These are based on understandings of (beliefs about) what counts as education and teaching, how curriculum is tied to society, what subjects are worthy of learning, and how students learn and come to know things as well as any character traits to be fostered and encouraged (Sowell, 2000).

These philosophical beliefs inform teachers’ pedagogy (andragogy for adults); that is, perceptions of the purpose of education and a particular educational program, what content is of value, how students learn, what material, methods and resources to use, and how (and by whom) learning should be assessed. This cluster of ideas about education can “evolve openly or unwittingly during curriculum planning” (Ornstein, 1991, p. 104). Ideally, people will be conscious of their philosophical orientation because so much depends on it. This educational philosophy “determines principles for guiding actions” (Ornstein, 1991, p. 102).

A curriculum philosophy is reflected in the stated or implied vision, values and shared understandings of learning that are inherent in a particular program of study (Sowell, 2000). It also reflects the curriculum planners’ sense of “a particular purpose of education [that arises from] subject matter, needs of society and culture, and needs and interests of learners” (Sowell, 2000, p. 41). The particular philosophy to which any curriculum is committed serves as the starting point and foundation for curriculum planning and decision making about the aims, means and ends of education (Ornstein, 1991; Sowell, 2000).

In an ideal world, a curriculum’s philosophy of education is an actual written-out statement (or set of statements) that identifies and clarifies what curriculum planners believed, valued and understood with respect to what counts as education, teaching and learning. It is placed at the very front of the curriculum document and represents an “organised body of knowledge and opinion on education, both as it is conceptualised and as it is practised. [It] inspires and directs educational planning, programs and processes in any given setting” (Lambert, 2019).

Educational Philosophy for Transdisciplinary Curricula

A transdisciplinary approach to organizing a curriculum especially entails “dissolving the boundaries between the conventional disciplines [and society] and organizing teaching and learning around the construction of meaning in the context of real-world problems” (UNESCO, 2012; see also Nicolescu, 2005). The intent is to teach students how to collaborate with others inside and beyond the academy to analyze real-time wicked problems so solutions can be developed via real world experiences. Because of its significance in learning, any curriculum with transdisciplinary intent must be grounded in sound philosophical considerations (Babadi et al., 2018; Etras, 2000).

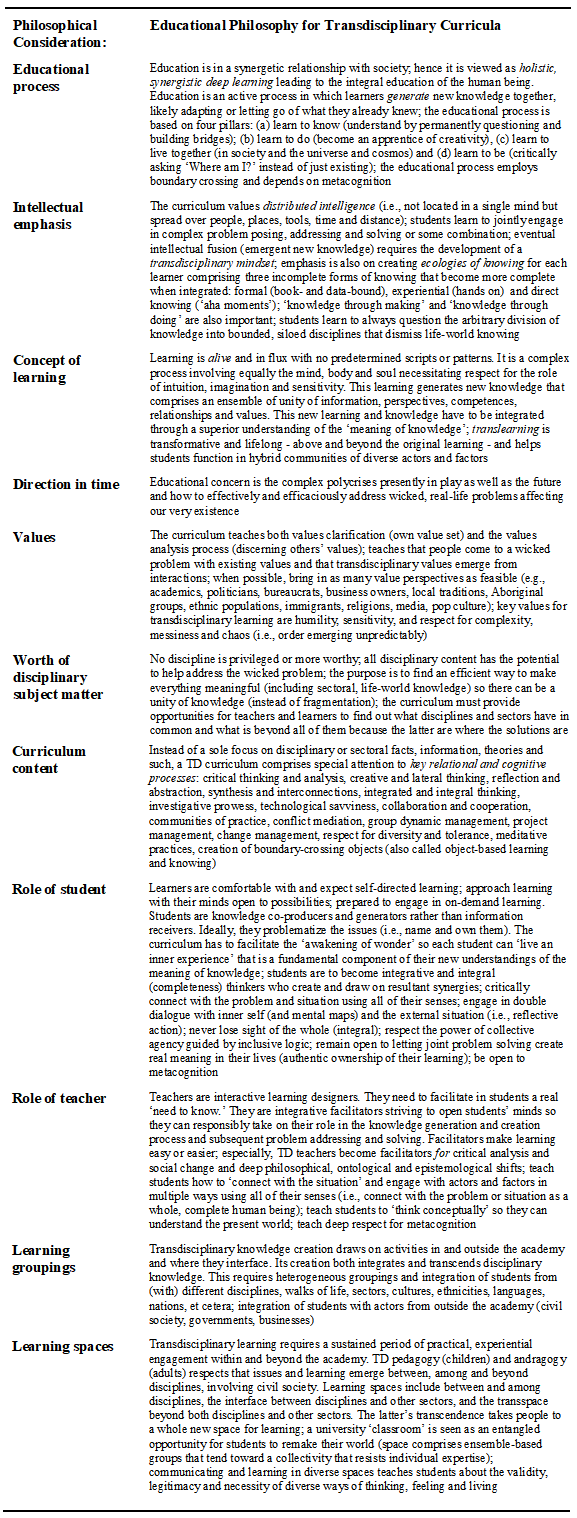

To that end, inspired by Ornstein’s (1991) criteria for profiling traditional and progressive educational philosophies, Table 1 presents an inaugural attempt to comprehensively profile the educational philosophy for a transdisciplinary curriculum. A tabular approach was used instead of the conventional narrative text with subheadings, anticipating ease of comparison to other educational philosophies (e.g., perennialism, essentialism, academic rationalism, social reconstructivism, progressivism, existentialism). The information contained therein reflects insight drawn from multiple sources with most of the reviewed literature published within the last five years (see Constantino, 2018; Delors, 1996; Derry & Fischer, 2005; Dielman & Juarez-Najera, 2015; Ertas, 2000; Evans, 2015; Heron, 2017; Hyun, 2011; Jeder, 2014; McGregor, 2017; McGregor & Volckmann, 2011; Rasi, Ruokamo, & Maasiita, 2017; Stavinschi & Mureşan, 2014).

Table 1. Educational Philosophy for Transdisciplinary Curricula

Curriculum Rationale

As noted, a rationale is a set of reasons for a course of action. These reasons can be used to explain and justify something (Anderson, 2014). Written rationales placed at the beginning of a curriculum document set out a full justification for what is contained in the curriculum and why. Their inclusion tells readers that the curriculum planners have thoughtfully reflected upon what counts as teaching and learning thereby staving off impressions that what is taught is simply expedient (i.e., advisable on practical rather than morally-sound grounds). With a rationale, curriculum planners can address push back and challenges from those who do not understand why a particular approach is being used or content and processes are being taught (Brown, 1994).

As well, a rationale spells out the curriculum planners’ opinions on the value added for learners by completing the program of study. Why do students have to learn this curriculum? What do they gain? What would they lose if they did not learn it? What does society lose or gain? (Posner & Rudnitsky, 2001). To clarify, value (benefit) is added when a homogenous product or service (e.g., a curriculum) is changed or enhanced to provide learners with features or add ons that give a greater perception of value (“Value added,” 2018). The rationale serves to convince others of the ‘value of the learning’ contained in the curriculum. ‘It is important and significant because . . . .’

The rationale begins by presenting the problem or situation to be addressed in the curriculum and can clarify what it is not about. It justifies both the learnings that students are supposed to acquire and the methods and procedures used to teach the content and processes. A well-articulated rationale will identify the expectations (roles) of teachers and learners. It will address basic values and assumptions around the (a) the role of society in learning and education, (b) the curriculum’s link with the future and (c) what knowledge is most useful and for what purposes. The rationale should attempt to describe what the learners are like – their needs, interests, abilities and challenges. And, if relevant, the rationale should relate curricular learnings to social responsibilities, societal constraints or both (Posner & Rudnitsky, 2001).

Rationale for Transdisciplinary Curricula

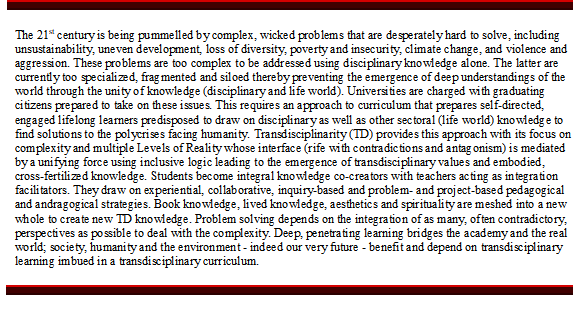

Figure 1 contains recommended text for a rationale statement for transdisciplinary curricula. The intent is to provide TD curriculum architects and planners with a narrative that respects the aforementioned criteria for a sound rationale (Brown, 1994; Posner & Rudnitsky, 2001). The narrative is offered as a template for others to embrace in its entirety or edit to their context and circumstances as they anticipate degrees of resistance and openness to adding a TD curriculum to their institution’s educational offerings.

Figure 1. Proposed narrative for rationale for transdisciplinary curricula.

Conclusions

Hyun (2011) believed that a higher education transdisciplinary curriculum should “prepare the next generation for engagement that may lead to socially responsive and humanistically sound action for sustainable human community” (p. 3). Contemporary universities have a social responsibility to do so (Hyun, 2011). Achieving such an imperative requires the formation and articulation of transdisciplinary curricula replete with TD’s unique educational philosophy and rationale. Etras (2000, p.15) was convinced that a transdisciplinary curriculum philosophy and sound rationale “must be fleshed out.” This paper tendered a discussion of what each of these might look like when informed by Nicolescuian transdisciplinarity (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Eventual agreement on what constitutes both is necessary because higher education institutions have a “serious ethical obligation to interest themselves in borderless transdisciplinary and transcultural connections and to engage in curriculum, teaching, research inquiry, and methodological transformation in a transgressive mode” (Hyun, 2011, p. 7). Transgressive means to go beyond accepted or imposed boundaries – to step across and beyond into a new space. The power of transdisciplinary learning can be released if transgressive curriculum planners and architects clearly and purposefully articulate a TD educational philosophy and justify (with a rationale) why this approach is so necessary in the 21st century. Such intentional curriculum-design actions pave the way for more higher education institutions to embrace transdisciplinarity’s potential and ensure its realization.

References

Albright, J. (2016). Transdisciplinarity in curricular theory and practice. In D. Wyse, L. Hayward, & J. Pandya (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 525-543). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Anderson, S. (Ed.). (2014). Collins English dictionary (12th ed.). Glasgow, Scotland: HarperCollins.

Babadi, A., Varaki, B. S., Khandaghi, M., & Karami, M. (2018). Transdisciplinary curriculum inspired by the causal layered analysis: Philosophical assumptions, implications and a pedagogical model [Abstract]. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 8(16), 7-34.

Boggs D. L. (1981). Philosophies at issue. In B. W. Kreitlow (Ed.), Examining controversies in adult education (pp.1-10). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brown, J. E. (1994). SLATE starter sheet: How to write a rationale. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Clark University. (2019). Transdisciplinary curriculum. Retrieved from Clark University website: https://www.clarku.edu/schools/idce/transdisciplinary-curriculum/

Costantino, T. (2018). STEAM by another name: Transdisciplinary practice in art and design education. Arts Education Policy Review, 119(2), 100-106.

Dieleman, H., & Jiarez-Najera, M. (2015). Introducing a transdisciplinary curriculum to foster student citizenship: A challenge beyond curricula reform. International Journal of Higher Education and Sustainability, 1(1), 3-18.

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Derry, S., & Fischer, G. (2005). Transdisciplinary graduate education. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Conference, Montreal, QU. Retrieved from http://l3d.cs.colorado.edu/~gerhard/papers/transdisciplinary-sharon.pdf

Etras, A. (2000). The Academy of Transdisciplinary Education and Research (ACTER). Journal of Integrated Design and Process Science, 4(4), 13-19.

Evans, T. L. ( 2015). Transdisciplinary collaborations for sustainability education: Institutional and intragroup challenges and opportunities. Policy Futures in Education, 13(1), 70-96.

Güvenen, O. (2016). Transdisciplinary science methodology as a necessary condition in research and education. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science, 7, 69-78.

Harper, D. (2019). Online etymology dictionary. Lancaster, PA. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com/

Heron, J. (2017, November 22). Trans-formational education [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/jonathanheron/entry/trans-formational_education/

Hyun, E. (2011). Transdisciplinary higher education curriculum: A complicated cultural artifact. Research in Higher Education Journal, 11. Retrieved from http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/11753.pdf

Jeder, D. (2014). Transdisciplinarity: The advantage of a holistic approach to life. Procedia, 137(9), 127-131.

Khoo, S-M., Haapakoski, J., Hellstén, M., & Malone, J. (2018). Moving from interdisciplinary research to transdisciplinary educational ethics: Bridging epistemological differences in researching higher education internationalization(s). European Educational Research Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118781223

Klein, J. T. (2008). Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: A literature review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), S116-S123.

Lambert, I. (2017, September 19). Educational philosophy: What is it all about? [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.tsc.nsw.edu.au/tscnews/educational-philosophy-what-is-it-all-about

Lauritzen, C., & Jaeger, M. (1994). Language arts teacher education within a transdisciplinary curriculum. Language Arts, 71(8), 581-587.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2015). The Nicolescuian and Zurich approaches to transdisciplinarity. Integral Leadership Review, 15(3). Retrieved from http://integralleadershipreview.com/13135-616-the-nicolescuian-and-zurich-approaches-to-transdisciplinarity/

McGregor, S. L. T. (2017). Transdisciplinary pedagogy in higher education: Transdisciplinary learning, learning cycles, and habits of minds. In P. Gibbs (Ed.), Transdisciplinary higher education (pp. 3-16). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2018). Philosophical underpinnings of the transdisciplinary research methodology. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science, 9, 182-198.

McGregor, S. L. T., & Volckmann, R. (2011). Transversity: Transdisciplinarity approaches in higher education. Tucson, AZ: Integral Publishers.

Metcalfe, J., & Shimamura, A. P. (1994). Metacognition: Knowing about knowing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nicolescu, B. (2005). Towards transdisciplinary education and learning. Paper presented at the Metanexus Institute Conference, Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from http://www.metanexus.net/archive/conference2005/pdf/nicolescu.pdf

Nicolescu, B. (2014). From modernity to cosmodernity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Ornstein, A. C. (1991). Philosophy as a basis for curriculum decisions. The High School Journal, 74(2), 102-109.

Posner, G., & Rudnitsky, A. (2001). Course design (6th ed). New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Rasi, P., Ruokamo, H., & Maasiita, M. (2017). Towards a culturally inclusive, integrated, and transdisciplinary media education curriculum: Case study of an international MA program at the University of Lapland. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 9(1), 22-35.

Reys, R., Reys, B., Lapan, R., Holliday, G., & Wasman, D. (2003). Assessing the impact of standards-based middle grades mathematics curriculum materials on student achievement. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 34(1), 74–95.

Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Saunders, E. M. (2009). The transdisciplinary andragogy for leadership development in a postmodern context. Paper presented at the American Society of Business and Behavioral Science Conference, Las Vegas, NV.

Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1-2), 113–125.

Smyth, T. S. (2017). Transdisciplinary pedagogy: A competency based approach for teachers and students to promote global sustainability. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 5(2), 64-72.

Sowell, E. (2000). Curriculum (2nd ed). Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall.

Stavinschi, M., & Mureşan, M. (2014, December). Astronomy in the frame of transdisciplinary education. Global Education Magazine, 10. Retrieved from http://www.globaleducationmagazine.com/astronomy-frame-transdisciplinary-education/

UNESCO. (2012). General education quality analysis/diagnosis framework [E-book version]. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/glossary-curriculum-terminology/t/transdisciplinary-approach

Value added. (2018). In Investopedia online dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/valueadded.asp

About the Author

Sue L. T. McGregor (PhD, IPHE, Professor Emerita MSVU) is an active independent researcher, analyst and scholar in the areas of transdisciplinarity, home economics philosophy and leadership, consumer policy and education, and research paradigms and methodologies. She recently published Understanding and Evaluating Research(SAGE, 2018). Her scholarship is at her professional website:www.consultmcgregor.com