Melita Balas Rant

Introduction

A central regularity discovered by the neo-Piagetian school of constructive human development is that adults (like children) can further evolve in their cognitive, affective and behavioral tendencies. Second, the main tendency is an evolution towards greater complexity, to reconstruct more inclusive identities, and adopt more complex meaning-making and value systems. Third, regularity is that stage of adult development’s impact on the way people interact and form relationships. Thus we derived a premise that a stage of adult development also significantly determines how people approach “the act of giving”, form the intention behind the act and perceive its consequences. Thus, the primal research question is: how is the “act of giving” influenced by the stage of adult development?

Since the transition from one stage to another is a very long-term process imbued by a sense of stuckness and inner turmoil (Petriglieri, 2007; Kegan, Lahey, 2001), we have also asked: what are the possible approaches that can transform the intention and perception of the “act of giving”? Based on the literature review, we have selected the contemplative practice of prayer as a possible intervention method.

With these two research questions, we entered two research gaps that exist within the organizational studies. First, the recognition that different employees occupy different stages of adult development and that stage positioning defines much of the psychological makeup of the person. Research evidence is showing that the stage of adult development significantly impacts personality traits (Vincent, 2014). The impact of personality traits has been much researched within leadership and organizational studies, however, the recognition that personality traits can evolve calls for a needed study of the impacts of the stage of adult development on different organizational variables that predict organizational effectiveness.

Secondly, there is missing research on the effectiveness of contemplative prayer on different work-related issues. In Western-centric society, prayer is much more embedded in people’s everyday routines than meditation, though there is increasing adoption of meditation and other mindfulness techniques within organizational settings.

The paper is structured in three parts: the first section forms a literature review on human/adult development. The second section outlines the research design. The third section presents discusses the results and derives some tentative implications for organizations.

Adult Development and Consciousness

Plethora of Western-centric research known as the constructive school of adult development revealed that not only children but also adults as well can and do develop in a stages-wise manner (Baldwin, 1895; Piaget, 1954, 1970; Selman, 1971, 1980, Kolberg, 1958, 1984; Loevinger, 1976; Kegan, 1982, 1994; Cook-Greuter, 2000, 2005, 2013; Tolbert, & Rooke, 1998, 2005; Wilber, 1995, 2000, 2007; Fisher, 1980; Reams, 2014; Dawson, 2002; Graves, 1971, 1981; Becks, & Cowan, 1996). On the most generic level at each stage evolves a subject-object relationship (Kegan, 1982; 1994). A subject is a being who has a unique consciousness and/or unique personal experiences. It is the nature of the self that holds a relationship with another entity that exists, seemingly, outside itself (called an “object”) (Heartfield, 2002). An object is anything that the subject pays attention to – a so-called percept that can be anything from sensations, thoughts, feelings, dreams, illusions etc.; the way that way it attributes meaning to “what is” and, in that way, defines the experience of living that is unfolding in a human consciousness (Steiner, 1893). The essential activity of the subject is “thinking that performs the function of meaning-making”. Each successive stage of adult development is characterized by a unique structure of meaning-making (Kegan, 1982).

Adult evolution is prompted when a person encounters limits to the existing meaning-making structure and cannot come up with a resolution to the experienced challenges they encounter in life (this event is referred as evolutionary truce). One can resolve such a challenge only if she/he redefines the “subject-object” relationship in such a way that the subject becomes consciously aware of their own thoughts and feelings that were formerly held in sub-consciousness. When this process of introspection unfolds successfully, conscious awareness expands so that many more perspectives can be held in awareness simultaneously, and the identification pattern of self transcends and includes previous identifications.

Neo-Piagetian developmental scholars prefer to label distinct stages of awareness expansion as “orders of consciousness” (Kegan, 1982, 1994; Wilber, 1995, 2000, 2007). Kegan identified five generic orders of consciousness in human beings: the 1st order of consciousness is the incorporative sense of self; the 2nd order of consciousness is the imperialistic sense of the self; 3rd order of consciousness is the socialized sense of the self; the 4th order of consciousness is the self-authorizing capacity of the self; and finally, 5th order of consciousness is the self-transforming capacity of the self. The 1st order is typical for children, 2nd for adolescence, and 3rd, 4th and 5th for adults. Within these generic stages, neo-Piagetian scholars have discriminated two distinct variations of sub-stages for each order of consciousness. Review them in Appendix 1.

Graves (1971, 1981; Beck, & Cowan, 1996) also studied psychological maturity and the meaning-making system of humans using large scale qualitative research and identified that each stage of consciousness operates from a particular belief system (value MEME, vMEME; ideology, doctrine). vMEME is a program working from the subconscious awareness that determines how the person perceives and interprets the reality and behaviorally responds to it. Similar to Kegan’s finding, a change in vMEME occurs when the person experiences an inability to effectively deal with prevailing life conditions at an appropriate level of complexity. This dissonance forces a fading of the operative force field of a dominant vMEME, and activation of a new, higher-order vMEME. Each new vMEME transcends and includes the previous vMEME.

According to Whitehead (1978; Christian, 1959), this transcendence and inclusion of stages of consciousness, the transcendence and inclusion the subject-object relationship, and the identification patterns of the self (meaning-making structures or vMEME, moral judgment, etc.) is an evolutionary force of “prehension” working behind the conscious awareness. Prehension is the subconscious relationship between two moments of awareness, whereby what was momentarily in awareness becomes an object of awareness in the next moment, and this object impacts what is emerging in the now, within awareness. This influence is not purely deterministic. Within the non-determined components operates a higher-order creative force that imbues every particle within the universe and human consciousness.

From the meta-perspective on adult development Wilber (1995, 2000) and Cook-Greuter (2000) distinguish between two distinct phases: growing up, and waking up. In the growing up phase the individual experiences an increasing sense separation of the self from the outer world. Boundaries between the self and perceived outer world become more clear cut, human action becomes less instinctual and more driven by meaning-making through rational thinking. The peak of growing up is the evolution of the highly rationalized sense of self, with a strong identity with clear boundaries, capable of making well-reasoned decisions, postponing gratifications and logically pursuing meaningful purposes; this is the aim of the effective Western-centric education (Piaget, 1954, 1970; Cook-Greuter, 2013). When the limits of reasoned action are discovered, the opposite developmental pattern may kick in and waking up starts unfolding. The waking up process is oriented “towards a more holistic, full-bodied, and integrated self that is fully aware of its inter-dependency with other systems and one can take a perspective on its fundamental non-separateness“ (Cook-Greuter, 2013; p. 51). Self-transforming adults with awakened consciousness are found in this second meta-phase (Kegan, 1982).

While Western-centric developmental psychologists mainly study stages of growing up phases, eastern contemplative traditions study stages of waking up (Wilber, 2000, 2007). Wilber proposes that major qualitative jumps in the evolution of humanity can occur only when we will fully integrate and participate in the two complementary traditions of human development: ancient, contemplative Eastern and modern, rationalistic Western tradition. Additionally, the integration of these two traditions provides a superior framework not only for the study of the evolving sense of self but also the study of human interactions. Thus we present a Wilberian integrative framework of human development (development of consciousness), complemented with the Graves/Loevinger/Kegan frameworks of adult stages of growing up.

The first adult stage of growing up is the stage of socialized self or 3rd order of consciousness, where the self fully takes-in (breathes in) definitions (value system, behavioral rules) of the relevant surrounding (Kegan, 1982, 1994). The self coheres through its alignment with, fidelity toward, and loyalty to that which the person (usually uncritically) identifies with. Loevinger (1976) pointed out the identification with surroundings can come in two distinct forms: identification with a group of people and identification with the value system. Such identification aims to reduce the sense of the fragility of the separated ego-self, whereby the person uncritically conforms to the group norms. This is labeled as conformist (Loevinger, 1976; Cook-Greuter, 2013). The prevailing doctrine in this stage is that the world is rough, limited in resources and one needs to fight for survival (Beck, Cowan, 1996). The self then evolves and identifies with the value system of the group, thus becoming a more self-aware contributor to the group (Loevinger, 1976; Cook-Greuter, 1985/revised 2013). The person adopts the doctrine that the world is divinely controlled and purposeful, thus obeying authority, having a sense of guilt and doing what is right (Beck, & Cowan, 1996). The person then develops challenges of meeting the competing commitments to these groups/value systems and imposed expectations of those with whom identifies with (Kegan, 1994).

This evolutionary truce seeds the need for generating one’s own beliefs and values (ideology) through which one filters external expectations/demands of the surround, that identifies and evaluates options for actions, and makes choices based on their own, more personal ideology. Since this is a completely new way of constructing a sense of self, Kegan refers to the self-authoring mind or 4th order of consciousness (Kegan, 1982, 1994). Instead of the sense of self (identity) being written upon, the person becomes a maker of their own identity. The sense of self coheres through its alignment with its own belief system (ideology) also comes into two evolutionary variations. Loevinger (1976) refers to the conscientious stage, whose dominant ideology is that the world is full of opportunities, and one needs to test different options for success (Beck, Cowan, 1996). When a person becomes more aware of their own ideology and where it operates from, the person can then bring insight into how different normative positions of right/wrong, true/false affects perceptions and interpretations of reality. Since such insights create indecisiveness about many situations encountered in life, the person moves into the stage of an individualist (Loevinger, 1976). The dominant ideology becomes that the world is a shared habitat for all humanity; they are thus attracted to community work and personal growth (Beck, & Cowan, 1996).

A majority of the working adult population is situated in these stages of growing up. Only 1-2% of the adult population has been identified to move into the awakened 5th order of consciousness which carries the capacity to transform the self. Such adults awaken from the material realm and become more conscious of non-material realms of being such as subtle, causal and non-dual/witnessing (Wilber, 2000, 2007). Only in these non-material realms, one can consciously find the resolution to the either/or construction of reality, come up with the both-end integrated perspective of reality, become less attached (identified with) the outer world, and recognized the fluidity of meaning-making systems.

Contemplative traditions identify at least four realms. In addition to the material or gross realm, human conscious awareness can also access subtle, causal and witnessing/non-dual realms if properly mastered. The major contribution of Ken Wilber (2000, 2007; Combs, 2013) was the recognition that growing up and waking up are not only successive phases that occur in human evolution of consciousness, but that at each stage of growing up a person can consciously access any of the non-material realms of being. Thus, awakening at any given stage results in different states of consciousness. In general, at each stage of growing up, four modalities of wakefulness can unfold: gross, subtle, causal and witnessing/non-dual realms of being/existence.

The gross realm is defined as the everyday wakeful state in which a person, through their own sensory-motor system, experiences the external physical world. This is a realm of thoughts, sensations, images, feelings, and emotions that are induced in the inner world of the self through the interactions with different signals from the material world. In Eastern wisdom traditions, the wakeful state is the least awakened.

The subtle realm corresponds to the dream (REM) state, but it is more than just dreams. In a dream-like state, physical limitations from the gross realm are not present. Consciousness can enter a new subtle perspective on the self, others, and life in general. Infusion of additional more subtle perspectives can cause the person to be less identified with attachments from the gross realm; their behavior is less compelled by subconscious impulses, needs, indoctrinations, and belief systems. When the subtle is coming into awareness, many hidden and compelling forces can be resolved. Images that operate from the person’s subconsciousness come into their awareness to be resolved (Jung, 1912).

When waking up at a given stage kicks in, the person becomes consciously aware of the causal realm, which corresponds to dreamless sleep. This awareness is empty of feeling, emotions, thoughts, sensation, images, etc.[1] It is a state of blissful formlessness; the dissolution of the self. In this stage dis-identification is further strengthened. The most refined morality of waking-up is a conscious awareness of the witnessing/non-dual state. In this state, one is aware of what is rising and falling within the awareness (“I-am-ness”) without any attachment to the any of manifestations unfolding in the external world. In this realm a person can experience a sense of oneness with everything, where everything is connected, but also transitory and illusory, and thus no identifications arise. Wilber refers to no-identification as a supreme identity and an absolute subjectivity.

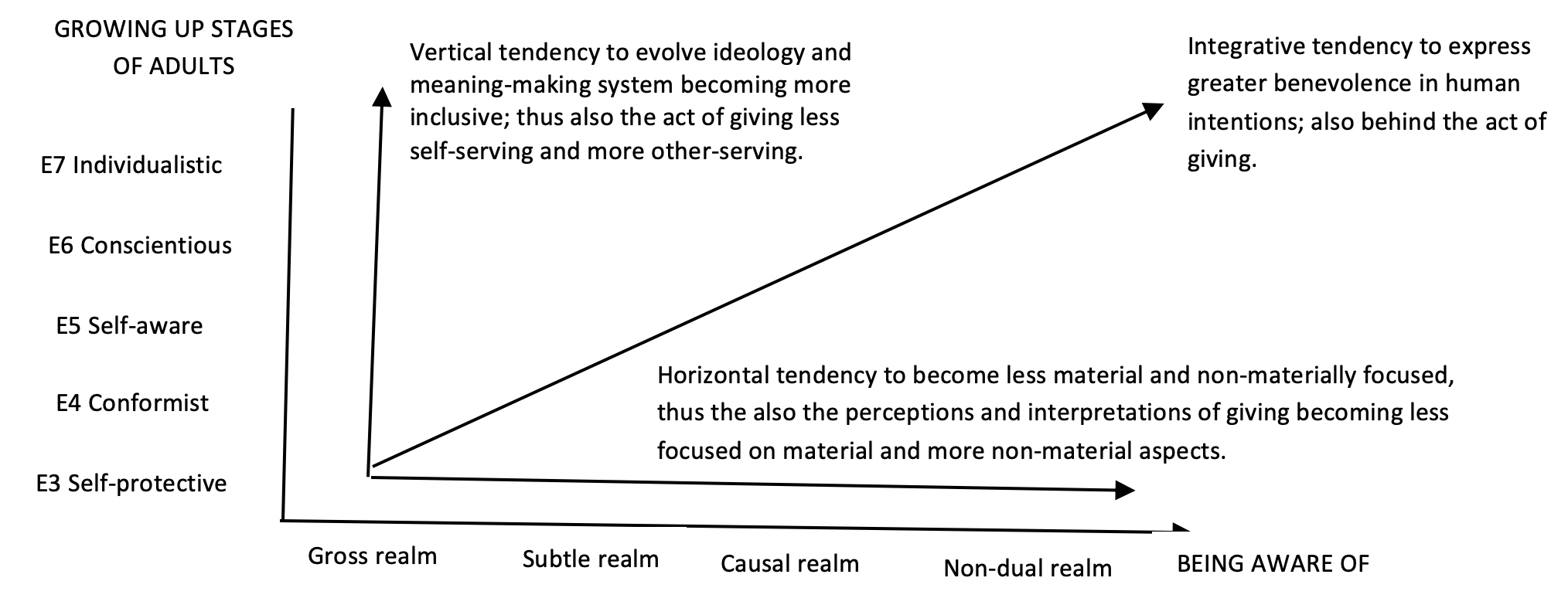

Wilber (2000, 2007) and Combs (2013) have developed a lattice framework of adult development that integrates stages of growing up with states of waking up. Stages of growing up differ slightly in terms of foci among researchers (look Appendix 1). In our analytical framework, we have adopted Loevinger’s (1976) stages of adult development and integrated them combined with different states of consciousness (Wilber 2007b, Combs, 2013) (Figure 1). This integrative framework serves as a theoretical background for the study of the action of giving from the perspective of a giver (evolution of intention and expectations), through different evolutionary stages (indicated by the vertical movement in Figure 1). The Neo-Piagetian school of adult developments states that each successive stage integrates more and more perspectives into coherent wholes through the process of transcending and including (Wilber, 2000; Reams, 2014; Cook-Greuter, 2005). We expect that lower stages of adult development perceive and interpret the act of giving in a more transactional nature, while later stages use a more transformational outlook on the underlying intentions and consequences of the act of giving. The vertical dimension works as an evolutionary force for more inclusive meaning-making systems and expanded identification patterns, and therefore the relational focus on the act of giving should become less self-focused and more other-focused as one evolves vertically. Horizontal movement is characterized by the expansion of conscious awareness to the non-material realms, with less determination of the material (gross) realm on the construction of the self.

Figure 1: Wilber-Comb lattice of state-stages modified by Loevinger’s developmental stages

The vertical movement of consciousness is driven by the evolutionary force presented by Whitehead’s (1978) concept of “prehension”, thus it is programmed into human beings and the universe. But what about horizontal movement from the gross, subtle, causal to the witnessing non-dual realm? Eastern contemplative traditions propose that movement can be purposefully induced by different contemplative practices (Kabatt-Zin, 2009; Brown, & Ryan, 2003); but same can be achieved also by anesthetics (Brown, Purdon, & Van Dort, 2011), non-natural psychedelics, narcotics, sedatives, and stimulant drugs (1966; Tart, 1972), and natural plants like peyote, ibogaine, and ayahuasca (Brito et al., 1996; Shanon, 2003; Winkelman, 2014). However, such approaches to the expansion of consciousness are not legitimate in Western society. The most legitimate Western-centric contemplative practice are prayer and mindfulness (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003; Knabb, 2012; Stratton, 2015; Whitford, & Olver, 2011).

The positive impact of mindfulness on psychological and physical wellbeing has been increasingly supported by a body of research evidence (Grossman et al., 2004; Chiesa, & Serretti, 2009; Eberth, & Sedlmeier, 2012; Khoury et al., 2013). A much smaller research volume has been established on the impact of prayer on psychological and physical on human wellbeing. An emerging line of research reveals a positive effect of introspective prayer on health-recovery (Masters, & Spielmans, 2007; Hollywell, & Walker, 2009), psychological wellbeing (Francis et al., 2008; Jantos, & Kiat, 2007) and quality of interpersonal relationships (Beach et al., 2008). Specifically, the introspective prayer of hope, adult attachment, and forgiveness revealed significant positive impact on moral upliftment, gratitude for life (Lalbert et al., 2009), quality of interpersonal relationships like marital fidelity (Beach et al., 2008; Finchanm et al., 2001), trust and unity with significant others (Lalbert et al., 2009).

A research gap exists within a domain of the effectiveness of mindfulness and prayer on progression through vertical stages and horizontal state-stages of adult development. In our research design, we study the impact of prayer on the transformation of the perceptions and interpretations of the act of giving within given state-stages, and thus we now provide some interesting insights for above mentioned research gap.

Research Design

Identification of the adult development stage on the vertical dimension

We adopted the Loevinger’s (1976) framework of ego stages in the growing up phase. Therefore in our research we focus on five main adult growing up stages ranging from self-protective (Ego #3 stage, or E#), conformist (E4), self-aware (E5), conscientious (E6) and individualistic stage (E7). These stages are identified through a sentence completion test. We used adopted Loevinger’s abbreviated sentence completion test (WUSCT) composed of 18 stem roots (“Raising a family…; Being with other people…; My thoughts…; What gets me into trouble is…; Education…; When people are helpless…; A man’s job is…; I feel sorry…; Rules are…; I can’t stand people who…; I am…; My main problem is …; My emotions…; A good mother…; My conscience bothers me…; A man (women) should always…; The meaning of life is…; Happiness is…)”. We identified the stages by decoding with the guidelines provided in the WUSCT decoding manual (Hy, & Loevinger, 1996). Decoding was done by two decoders, both of whom are experts in the field of constructive approaches to adult development, and have substantial experience with WUSCT decoding procedure. Cohen’s kappa is above 98,2%, indicating excellent inter-rater reliability (Appendix 2).

As an intervention method that (might) induce horizontal movement in Figure 1, we have selected prayer (not mindfulness, which is more regularly studied in academia) due to several reasons: (1) It is a prevailing contemplative practice in Western-centric society that is culturally embedded; (2) criteria for selecting likely candidates were easier to identify (younger Christian population that is actively engaged into different modalities of beneficiary humanitarian action in Slovenia and across borders); (3) prayer has been gaining the research interest in medical studies and (mainly positive) psychology over the last two decades (Jantos, & Kiat, 2007; Levine, 2008).

Research Setting and Data Gathering

The sentence completion test, with a reflection question, was placed on the e-platform (www.enka.com). Data has been gathered over a period of time from December 2018-September 2019 (still in the gathering mode among the subgroup that is “praying). First, the data has been gathered among so-called “ordinary” people of non-prayers. The request was sent to a group to full-time graduate students, and part-time post-graduate students that were attending the course “Building Leadership Capacity”. All were asked to forward the test to their peers and others they know that might find the test interesting. To motivate for the test, all respondents were offered written coaching feedback on their dominant adult developmental stage. In the second data, we have also conducted the same test among students from other faculties within the University of Ljubljana. Data gathered in these two steps composed group 1.

In step three, we send the request to the young Christian population active under the Catholic Youth Institute of Slovenia. They formed Group 2, where we also requested them to pray before answering the question. They were also requested to select a prayer that would most likely induce a feeling of serenity, connectedness with others, and a sense of hope. Only after the act of contemplative prayer, they are asked to reflect on: “what are the expected and unexpected consequences of giving (based on your personal experience)?” The test was conducted in the Slovene language.

Method

Answers on the reflective question, “what are expected and unexpected consequences of giving (based on your personal experience)?” were analyzed by the inductive approach of grounded theory (Glaser, Strauss, 1967; Corbin, Strauss, 1990). In the theoretical overview of adult development, we have layered a generic framing through which we have addressed the answers. This framing provides two perspectives from which we have studied the answers. First perspective is outer (material focus on the gross, real) vs. inner focus (focus on the inner life: sensations, feelings and thoughts) at each stage. The second perspective focuses on serving self vs. other at each stage. These two perspective form the two generic categories from which we approach our data analysis.

The interpretations of the intentions, and the perception of expected/unexpected consequences of the act of giving (from the perspective of the giver) at each stage were first codified, with similar codes grouped into concepts. These concepts were grouped into the above two generic categories: outer vs. inner focus and self vs. other focus. This process was repeated for each stage subsequently, first for the ordinary group and then for the prayers. We have compared and contrasted these categorical groupings across stages, extracted similarities and differences, and implied developmental regularities for the “act of giving” that appear to be evolving through the growing up process. In the last step, we compared these groupings between the ordinary and praying groups, and extracted differences that seemed to arise with contemplative prayer. These differences were assessed from developmental regularities of the “act of giving” as they seem to be evolving through the growing up process. We have observed that, if the act of prayer was induced, the perceptions and interpretations of the “act of giving” were more evolved (does it correspond to a more evolved stage than the stage in which a person is situated in?).

Sample Characteristics

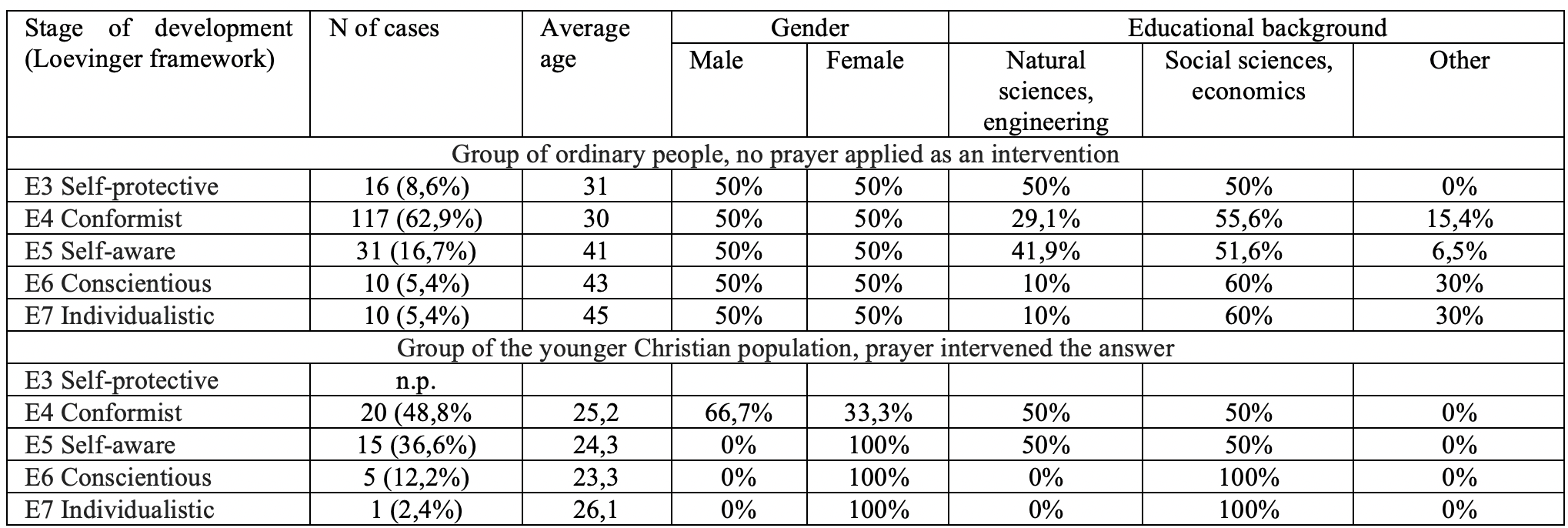

The sample size of the ordinary group (non-prayers) is 193 cases which ranged from E2-impulsive to E8-autonomous stages. In the analysis we have singled out only adult development stages of growing up (E2 is considered to be an underdeveloped adult; E8 is considered to be the first stage of waking up phase), and therefore we only included 184 cases in the analysis. For this group, the average age increases in each subsequent stage. The sample size of the “praying” group, for whom the praying intervention has been inserted before answering the question, accounts for only 40 cases (however, our data gathering process is still open, and so by the end of September we expect a total group size of 200 cases). In this small sample, the distinct difference is found in terms of average age distribution across the stages. For some reason, age does not increase as we transition from lower to higher stages of growing up. Figure 2 provides a summary of the socio-economic features of both sampled groups.

Figure 2: The socio-economic features of both groups.

Results and Discussion

Perceptions of the intentions for giving, and interpretations of the expected/unexpected consequences of the act of giving (from the perspective of giver) are presented in Appendix 3. For each stage of growing up, there is a set of prototypical reflective answers for each stage, both for ordinary people and prayers. In addition, for each stage there is also a summary of general prototypical cognitive, affective and behavioural tendencies for relating to other, identified by Loevinger (1976; Hy, & Loevinger, 1996) and reconfirmed by Cook-Greuter (2000, 2013)[2]. Furthermore, a special column in Appendix 3 presents perspectives which unfold interpretations of intentions for giving, and perceptions of expected/unexpected consequences resulted from the act of giving (from the perspective of the giver). Here we summarize the main distinctions across stages and between the two groups.

Distinctions Across Developmental Stages

The most obvious distinction across developmental stages is the change in perspective from self to other in a relationship. The second distinction is refocusing from a negative outlook to a positive outlook in the consequences. The third distinction is refocusing from the outer (material) focus to the inner focus (feeling) of life. The fourth distinction refocusing expectations. “What do I expect in return?” become less determined and pre-defined, thus creating a movement from expected consequences to unexpected consequences.

Movements in these four perspectives create a distinct pattern of how an “act of giving” evolves as the individual progresses through the stages of growing up. In this evolution, the expectations are less predefined, less material. The person becomes less self-serving focused, their outlook is less negative, their immediate responses of the receiver become less important and disturbing for the giver, and finally the person becomes less transactional in the “act of giving”.

Self-protective people among “ordinary” adults use plain language and do not exhibit much complexity in thinking and feeling. Their perceived consequences of giving are purely negative, short-term, material-focused, and self-focused. Some exemplary answers are: “Something in return / dissatisfaction of a person / the embarrassment of choosing a gift / spoiling.”

As one progress through “growing-up” stages, a sufficient transformation is made in the sense that expectations are loosening up (but not yet abandoned completely), conscious attention is more placed to the feeling life, and a slightly more positive outlook is embodied. Hence, the giver takes a more reflective and learning stance to the “act of giving”. The intentions behind the act of giving become more benevolent. Expectations are shifted from a material focus to the response in a form of positive feelings experienced in the receiver. If this does not happen, then disappointments kick in, although small errors in response are acceptable. In the case of disappointments, judgments and evaluations are made about materiality (too much material focus on the account of feeling life).

Individualist’s among “ordinary” adults can hold multiple cognitive and affective structures in one frame. Thus their responses tend to be much longer and multifaceted. Example: “I always want to give a gift-hit. Of course, gift-misses happen to me too. But giving is a kind of language, so if I give a gift-miss, then we speak two different languages. The unexpected consequence is that I start analyzing where I missed, and plan to improve that on the next occasion; I want to know you. This means a lot to me. The unexpected consequence is a reflection on how people care less and less: ‘Just bring present each year and we’re done.’ This happens in a personal and business context. This reflection is for me unpleasant. I estimate it is also a reflection of the times we are living in. At the end of the day, I just wish the receiver recognizes my effort in preparing and giving the gift to him. I shake hands, I hug, I kiss …”.

The identified developmental regularities of the “act of giving” are anchored and aligned with the generic regularities of vertical adult development: the evolution of more complex meaning-making systems (Kegan, 1982); a growing capacity for integrating multiple perspective-taking (Wilber, 1996, 2000); a movement self-identification patterns accrued from the social surround to one’s own ideology, shaped by personalized definitions of success, goodness, beauty, and truth (Kegan, 1994); a growing tolerance and acceptance of a range of differences across people, but conversely also being more overwhelmed by the emotional costs of careering, the negative aspect of the vMeme “HumanBond”, which is the core program from which individualists operate on (Becks, & Cowan, 1996; Appendix-Table 1); and finally, increased rationality and trust in science (Loevinger, 1976; Cook-Greuter, 2013).

If we want to create more benevolent relationships among people within the organizational settings (or any other social setting in general), we should bear in mind that any such attempt can be successfully implemented only if the organization employs people that occupy higher stages of growing up (self-aware and individualist). If this is not the case, then the only approach that promises success in the long-term is organizations (their HRM policies) systemically supporting the vertical development initiatives among their employees. However, the transition from one stage to another is long-term in nature. It also involves many mood alternations, increased anxiety, a sense of lost identity, distortions of meaning-making systems (the old does not work, new is not established yet), a strong sense of stuckness (Petriglieri, 2007) and strong cognitive resistance, and affective and behavioral resistance (Kegan, & Lahey, 2001). Persistent coaching and psychological support is required over this transitional time, which might be too costly for the company to afford it (Fitzgerald, & Berger, 2002).

Distinctions Between Ordinary and Praying Groups

The most obvious distinction between the two groups is that at any given stage of vertical development, “the act of transacting” seems to resemble a more evolved perspective and interpretation of the act of giving. Usually, the perspectives and interpretations resemble at least one, though in a few cases even two, levels higher. If the “praying” person operates from the conformist stage, his/her view on “act of giving” resembles a view from ordinary adults at the self-aware stage. Example: “Finding deep interest in the recipient of the gift, and investing my own effort into the act of giving. That’s a reward that creates good feelings.”

If the “praying” person operates from the self-aware stage, his/her view on “act of giving” resembles views that usually constitute ordinary adults at the conscientious stage. Example: “An act of giving is a tribute of time and attention to someone. When I give something, I usually expect someone’s smile or gratitude in return. I also get a smile and satisfaction, but sometimes also no response. The expected consequences of giving are that you are happy with yourself. The unexpected consequences are usually that you do not know if the person is grateful, and if the act of giving means something to her/him.”

If the “praying” person operates from the conscientious stage, his/her view on the “act of giving” resembles views that usually constitute ordinary adults at the individualist stage. Example: “Gifting is the act of selflessly giving oneself to others. Usually, in appreciation, I expect gratitude and nothing more from the other person. The expected consequences are a good feeling and a new impetus, but unexpected are some new insights that come.”

And finally, if the “praying” person operates from the individualist stage, his/her view on “act of giving” resembles views that usually constitute ordinary adults at the autonomous stage (E9). Example: “Gifting is giving without expecting anything else in return. It can be in the form of a gift, help, service to others… It is sharing oneself out of the desire to make someone happy. Well, that would be ideal. But always, even though I want to make happy someone, I do hope to get at least a word of “thank you” or a smile on the face of the person in return. It is hard to give without expecting anything in return. Both of these are usually realized, and I think this is the most I can get, because after that I also see that I did not miss, but helped in the right direction. It is precisely from situations where the gift is not well received that I can best see what my purpose was for it. Gifting and generosity are a constant in my life. I am blessed with such friends and family who encourage me to do so. I have been actively involved as a scout leader for five years now. I am the kind of human being who drops everything to help a friend, and I like to make various, loving surprises for people. Time and time again I find that leadership is probably more enriching for me than for the children I am entrusted with. Even though I devote most of my free time to them, and although they often step on nerves, and I have to go in and out of my comfort zone and do my best to create a safe space where they can learn, stumble, feel safe, grow, acquire new abilities … they are my best teachers.”

If we view contemplative practice (in our case prayer) as an instrument that shifts the “act of giving” among people at least one stage higher, then we can also propose that contemplative practices provide an alternative approach for organizations seeking to create more benevolent relationships among their employees. This approach is likely to be less expensive, and thus more affordable, producing results (modifications of relationships) faster and creating less internal turmoil; the turbulent period of transition between stages. Contemplative practices[3] create additional positive effects on the employees. Research evidence has confirmed better emotional regulation, less emotional exhaustion, greater job satisfaction and sense of wellbeing at work (Hülsheger et al., 2013; Good et al., 2016), less turnover, greater task performance, work effectiveness, and improved job engagement (Dane, 2011; Dane, & Brummel, 2014).

A major deficiency at the current stage of our data analysis is that we have only included 40 cases, thus the identified transformations in “the act of giving” that might be induced by contemplative, personalized prayers less unreliable.

Conclusions

We can conclude the stages of adult development impact the way people approach human interactions in general, and the act of giving in particular. However, more developed approaches to the act of giving can be induced by contemplative practice like prayer. Since these are only tentative research indications, we suggest more research within these two domains: (1) study of the impact of vertical stages of adult development on different organizational variables that predict organizational effectiveness over a longer time period, and (2) a study of the mediation’s effect, through different contemplative practices, on the relationship between stages of adult development and their impact on organizational effectiveness.

Endnotes

[1] In general, all people have dreams but not all are aware of them, and even fewer can consciously operate from the dream realm.

[2] Susan Cook-Greuter extended the work of Loevinger by identifying two additional stages of waking-up, which was initially missing in Loevinger’s work. Loevinger’s most developed stage identified in her group of adults was E8-Autonomous person, while Cook-Greuter repeated her studies two decades later, focusing primarily on the waking-up stages. She has singled out three additional stages: construct-aware, ego-aware and unitive stage. Cook-Greuter’s (2013) overview of all stages can be accessed: http://www.cook-greuter.com/Cook-Greuter%209%20levels%20paper%20new%201.1’14%2097p%5B1%5D.pdf.

[3] Only the effects of mindful breathing and meditation have been researched; effects of the contemplative prayer on the individual and organizational level at work, so far, has not yet been researched.

References:

- Baldwin, J., Mark. (1895). Mental development of the child and the race. London: McMillan.

- Beach, Steven; Hurt, Tera; Fincham, Frank; Franklin, Kameron; McNair, LIly; Stanley, Scott (2011). “Enhancing Marital Enrichment Through Spirituality: Efficacy Data for Prayer Focused Relationship Enhancement”. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 3 (3): 201–216.

- Beck, D. E., & Cowan, C. (1996). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values. Leadership and Change. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Beck, D., & Cowan, C. (1996). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Brito G. S., Neves, E. S., & Oberlaender, G. (1996). Human psychopharmacology of hoasca, a plant hallucinogen used in ritual context in Brazil. The Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 184(2), 86-94.

- Brown, E. N., Purdon, P. L., & Van Dort, C. J. (2011). General anesthesia and altered states of arousal: a systems neuroscience analysis. Annual review of neuroscience, 34, 601-628.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology, 84(4), 822.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology, 84(4), 822.

- Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. The journal of alternative and complementary medicine, 15(5), 593-600.

- Christian, W. A. (1959). An Interpretation of Whitehead’s Metaphysics,. Philosophy 37 (142):365-366

- Combs, A. (2013). Ken Wilber’s Contribution to Transpersonal Psychology. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of transpersonal psychology, 166.

- Cook-Greuter, S.R. (2005). Ego development: Nine levels of increasing embrace. Unpublished manuscript.

- Cook-Greuter, S. R. (1985/revised 2013). Nine Levels Of Increasing Embrace In Ego Development: A Full-Spectrum Theory Of Vertical Growth And Meaning Making. Accessed on: Http://www.cook-greuter.com/Cook-Greuter%209%20levels%20paper%20new%201.1’14%2097p%5B1%5D.pdf.

- Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2000). Mature ego development: A gateway to ego transcendence?. Journal of Adult Development, 7(4), 227-240.

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21.

- Dane, E. (2011). Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. Journal of Management, 37(4), 997-1018

- Dane, E., & Brummel, B. J. (2014). Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention. Human Relations, 67(1), 105-128.

- Eberth, J., & Sedlmeier, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 3(3), 174-189.

- Finchanm, F.; Lambert, N., & Beach, S. (2011). “Faith and Unfaithfulness: Can Praying for Your Partner Reduce Infidelity?”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 99 (4): 649–659.

- Fitzgerald, C., & Berger, J. G. (2002). Executive coaching. Palo Alta, CA: Davis-Black Publishing.

- Francis, L.; Robbins, M.; Lewis, C. A., & Barnes, L. P (2008). “Prayer and psychological health: A study among sixth-form pupils attending Catholic and Protestant schools in Northern Ireland” (PDF). Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 11 (1): 85–92.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., … & Lazar, S. W. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. Journal of Management, 42(1), 114-142.

- Graves, C. (1971).”Levels of Existence Related to Learning Systems,” Paper read at the Ninth Annual Conference of the National Society for Programmed Instruction, Rochester, New York, March 31,

- Graves, C. (1981). A summary statement the emergent, cyclical, double-helix model of the adult human biopsychosocial systems. Accessed on: http://coach2flow.com/c2f/class/Graves_Levels_of_Existence1981_summary.pdf

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57, 35–43.

- Heartfield, J. (2002). “Postmodernism and the ‘Death of the Subject'”. The Death of the Subject. https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/en/heartfield-james.htm

- Hollywell, C., & Walker, J. (2009). Private prayer as a suitable intervention for hospitalized patients: a critical review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(5), 637-651.

- Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310.

- Hy, L.X., & Loevinger, J. (1996). Measuring Ego Development. New York: Press Psychology.

- Jantos, M., & Kiat, H. (2007). Prayer as medicine: how much have we learned?. Medical Journal of Australia, 186, S51-S53.

- Jantos, M., & Kiat, H. (2007). Prayer as medicine: how much have we learned?. Medical Journal of Australia, 186, S51-S53.

- Jung, C. G. (1912/2012). Psychology of the Unconscious. Courier Corporation.

- Kabat‐Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 10(2), 144-156.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2009). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hachette Books.

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2001). How the way we talk can change the way we work: Seven languages for transformation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kegan, Robert (1994). In over our heads: the mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., … & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 33(6), 763-771.

- Knabb, J. J. (2012). Centering prayer as an alternative to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression relapse prevention. Journal of religion and health, 51(3), 908-924.

- Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: The nature and validity of moral stages. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

- Lambert, N.; Fincham, F.; Braithwaite, S.; Graham, S., & Beach, S. (2009). “Can Prayer Increase Gratitude”. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 1 (3): 139–149.

- Levine, M. (2008). Prayer as coping: A psychological analysis. Journal of health care chaplaincy, 15(2), 80-98.

- Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: Concepts and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ludwig, A. M. (1966). Altered states of consciousness. Archives of general Psychiatry, 15(3), 225-234.

- Masters, K. S., & Spielmans, G. I. (2007). Prayer and health: Review, meta-analysis, and research agenda. Journal of behavioral medicine, 30(4), 329-338.

- Petriglieri, G. (2007). Stuck in a moment: A developmental perspective on impasses. Transactional Analysis Journal, 37(3), 185-194.

- Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

- Piaget, J. (1970). Structuralism (C. Maschler, Trans.). New York: Harper & Row.

- Reams, J. (2014). A Brief Overview of Developmental Theory, or What I Learned in the FOLA Course. Integral Review: A Transdisciplinary & Transcultural Journal for New Thought, Research, & Praxis, 10(1).

- Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. R. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s developmental stage. Organization Development Journal, 16(1), 11-28.

- Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. R. (2005). Seven transformations of leadership. Harvard Business Review, April, 1-12.

- Selman, R.L. (1971). “Taking another’s perspective: Role-taking development in early childhood”. Child Development. 42: 1721–1734.

- Selman, R. L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. London: Academic Press.

- Shanon, B. (2003). Altered states and the study of consciousness—The case of ayahuasca. The Journal of mind and behavior, 125-153.

- Steiner, R. (1893/1995). Intuitive thinking as a spiritual path: A philosophy of freedom. SteinerBooks.

- Stratton, S. P. (2015). Mindfulness and contemplation: Secular and religious traditions in Western context. Counseling and Values, 60(1), 100-118.

- Tart, C. T. (1972). Altered states of consciousness. Oxford, England: Doubleday.

- Vincent, N. (2014). Evolving consciousness in leaders: Promoting late-stage conventional and postconventional development (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide.

- Whitehead, A.N. (1978). Process and Reality. New York: The Free Press.

- Whitford, H. S., & Olver, I. N. (2011). Prayer as a complementary therapy. In Cancer Forum (Vol. 35, No. 1, p. 27). The Cancer Council Australia.

- Wilber, K. (1995/2001). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Shambhala Publications.

- Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Shambhala Publications.

- Wilber, K. (2007). Integral spirituality: A startling new role for religion in the modern and postmodern world. Shambhala Publications.

- Winkelman, M. (2014). Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine, and Ayahuasca. Current drug abuse reviews, 7(2), 101-116.

Melita Balas Rant is an Assistant Professor of Management and Organization at the Faculty of Economics, the University of Ljubljana. Her research interests include the study of orders of consciousness and stages of adult development, personality changes alongside the adult development process, leadership behaviours at different stages; support mechanisms in stage transitions.