Synopsis of Integral Leadership Review’s Series

on Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education

Sue L. T. McGregor and Russ Volckmann

During 2010-2011, Russ Volckmann (Editor and publisher of the Integral Leadership Review) and Sue McGregor (Integral Leadership Council member) published six papers in a series about making the transdisciplinary (TD) university a reality. We profiled initiatives in United States, Europe (Germany, Austria), Mexico and Brazil, Australia, and Romania (the order they appeared in the series). We tried to cover each continent (except for Antarctica), managing to connect with all but Africa and Asia. Our overtures to initiatives in both South Africa and India were successful but we were unable to complete the interviews during the one year allotted for this TD-series. We hope to profile these in future issues.

In most instances, Russ and Sue became familiar with the general nuances of each initiative, and prepared a set of questions prior to making the initial contact. For each initiative, one or more persons were interviewed (taped audio/video). The interviews were transcribed and reframed in the formats published in the series. Prior to publication, when possible, contacts had the opportunity to vet the draft about their initiative, and changes were made to reflect their feedback. In all instances, contextual information was provided by Russ and Sue. Often, websites and/or follow up readings are suggested or hyperlinks were inserted directly into the text.

Our intent, once the series was complete, was to iteratively reread the entire collection to tease out a model approach (if such a thing exists) to transitioning higher education from multi- and interdisciplinary approaches to a transdisciplinary university (what we coined, a transversity). As we did this, we strove to gain insights into four five main issues (used to organize this article), augmented with a discussion of the various approaches profiled in the series:

1. why does transdisciplinary work need to be done;

2. what approaches are being used to bring a TD approach to higher education;

3. what strategies and messaging are involved in order to engage people with the idea and to garner their support while respecting resistance and push back to such a huge change in the way the academy is organized;

4. what is the nature of leadership required for initiating, implementing and sustaining transdisciplinary work; and,

5. what are the politics of getting the job done?

To be true to the voices reflected in the collection of articles comprising this series, what follows stems almost entirely from their interviews, with minimal augmentation. We do take ownership of the analysis and the integration of their diverse viewpoints, which in most instances were very complementary.

Why Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education

Every institution we interviewed expressed opinions about why they felt it was imperative to shift to a transuniversity. In summary, the world is facing a polycrisis, a situation where there is no one, single big problem – only a series of overlapping, interconnected problems. These interconnected, complex problems cannot be solved by disciplines working along within the academy using independent, fragmented, disciplinary-focused knowledge. Their solutions cannot ignore the voices of the people or of merged perspectives. The university can no longer perceive itself as the last bastion of knowledge, especially because that knowledge tends to be siloed in individual disciplines (separate departments, library holdings, conferences, journals and professional associations).

One of the challenges of higher education is to reconceptualize its relationship with the rest of society, both civic and corporate, so it can broaden its role to address the challenges of today’s world – the polycrisis. The fabric of the university has to reflect the fabric of society. Confining the solution of complex problems within traditional university settings leads to too few perspectives, let alone melded perspectives, and it sets up the university to be out of synch with reality. As noted at the Montclair State University website, “outside our familiar academic culture lies a vast, fraught, and endangered world.” Universities have to confront the challenge of being relevant to their communities, nation states and the world.

Those interviewed for this series tended to agree that transdisciplinarity does make a difference. It bridges the gap between sophisticated institutions (including colleges and universities), communities (society) and the private sector. Most especially, a transdisciplinary approach joins individuals from many academic disciplines with members of society (civic and corporate) to address challenges that transcend any one discipline within the academy. Through this process, the university can play an integrator role to (re)establish an active dialogue with other forms of knowledge. Through dialogue, transversities would bring together community and corporate perspectives with different, merged, disciplinary perspectives to solve the myriad of complex problems facing humanity.

Variety of Approaches to Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education

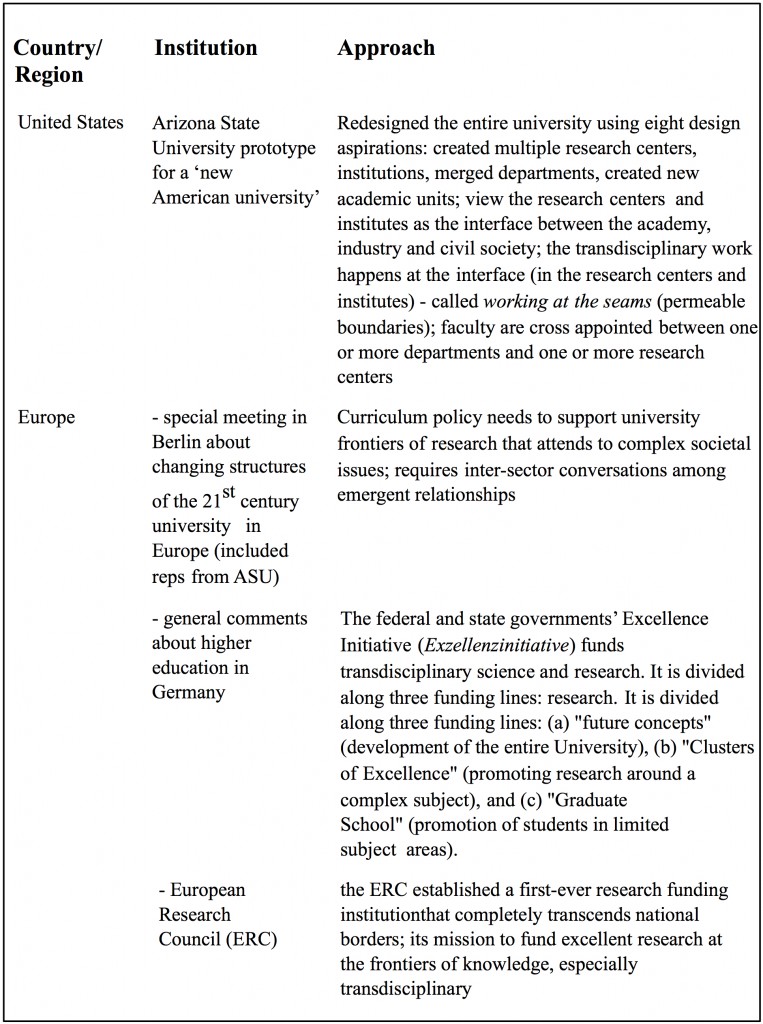

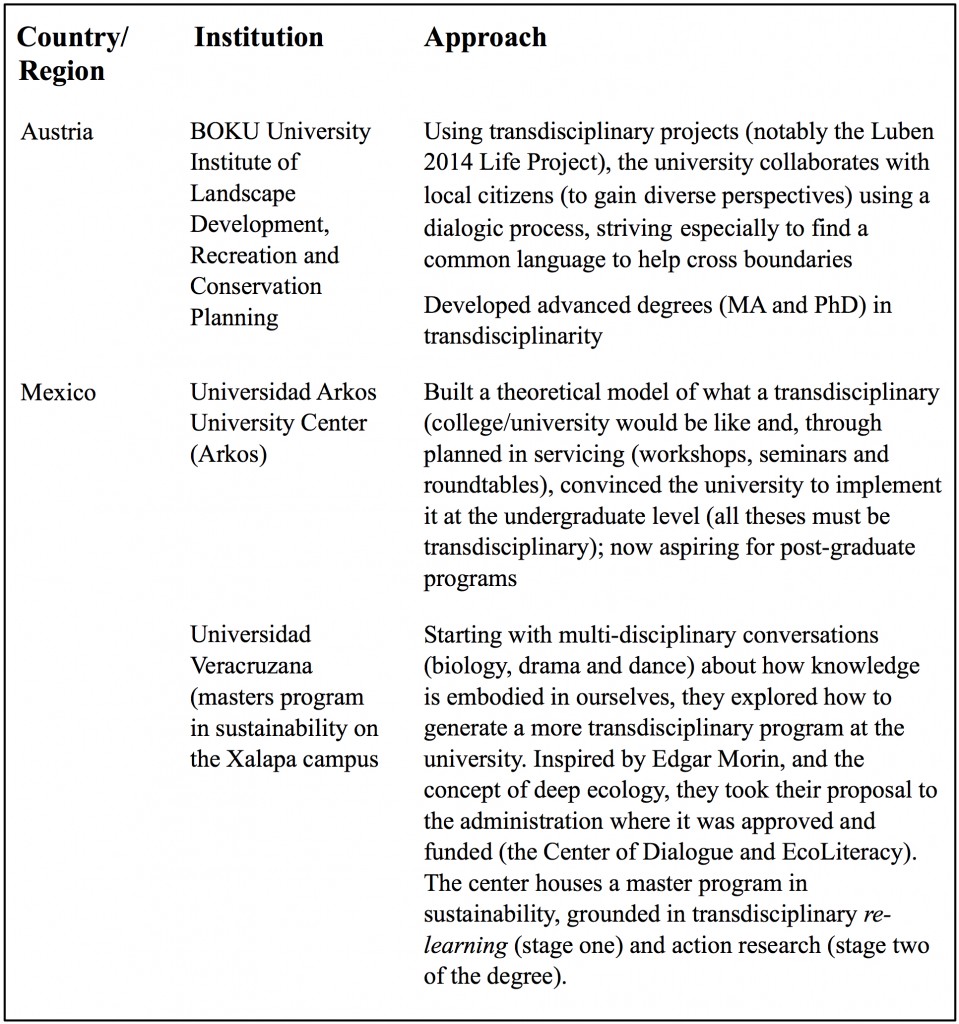

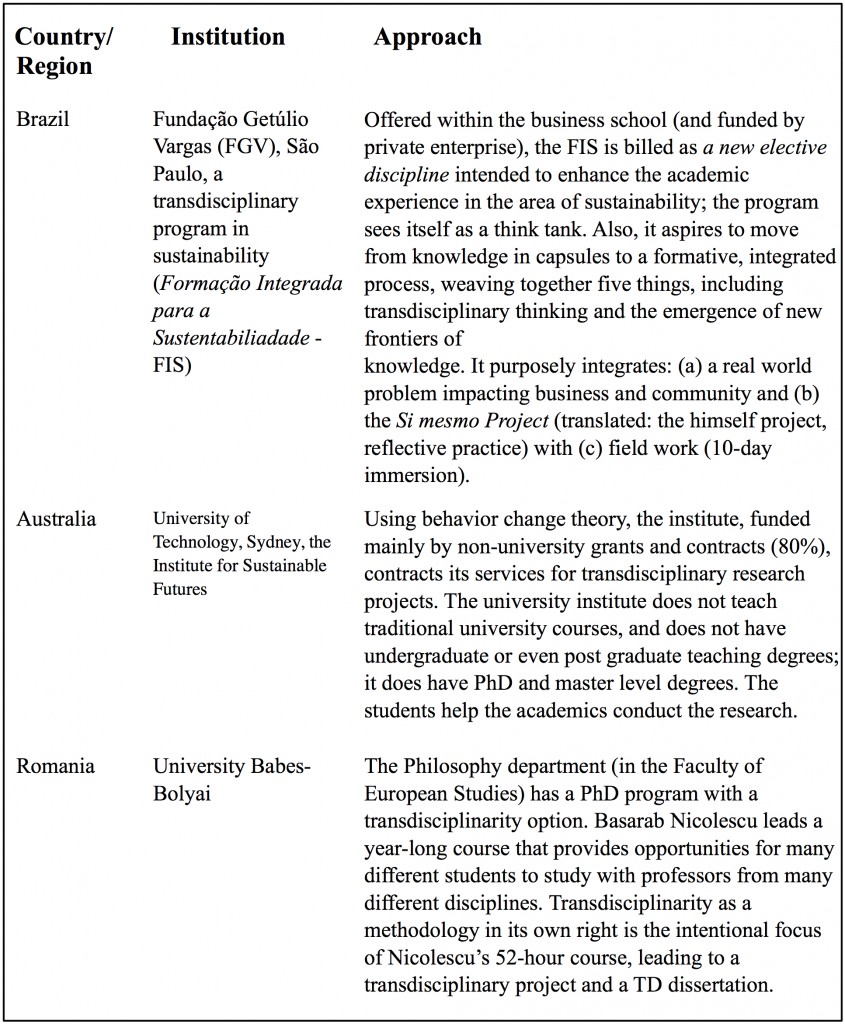

This series looked at initiatives in six universities and one research council (see Table 1, and we recommend that you read it). They ranged from: (a) redesigning entire universities to a transdisciplinary perspective, (b) designing first-ever transdisciplinary master or doctoral degrees for a university, and (c) ensuring external funding for transdisciplinary research initiatives within universities, to (d) university-coordinated transdisciplinary projects with industry and/or communities, and (e) recognition of the need for inter-sectoral conversations about how higher education curricula policy can change to reflect 21st century problems. There was no one way to go about bringing transdisciplinarity to higher education. We think it depends very much on the context and on leadership (to be discussed shortly).

Table 1: Programs Surveyed

Strategies and Messaging to Get and Keep People Engaged with Transdisciplinarity

Transitioning to a transdisciplinary approach, or convincing people of its merit, requires constant messaging and innovative strategies over a span of time. Transdisciplinarity is a huge paradigm shift from interdisciplinarity and especially from multi- and mono-disciplinarity. McGregor (2007) identified many obstacles to this change process, but the following text reflects ideas extrapolated from those interviewed for our series. They drew on their lived experiences as they strove to reorient entire universities, design new undergraduate, graduate and post- graduate degree programs (even eschew the former), garner different research funding formulas, and/or engage in project-oriented, university-coordinated scholarship with communities and with the industry sector.

The following section describes the insights gained from those we interviewed about strategies and messaging that worked or are proposed in order for transdisciplinary work to succeed. The discussion is organized by the disciplinary level, faculty members and students. As is evident, most of their comments pertained to convincing fellow faculty members to initiate, implement and sustain transdisciplinary work.

Disciplinary Level

Universities striving for some degree of transdisciplinarity have to constantly message that disciplines should not be abolished; rather, their varying perspectives are needed to solve complex problems. However, disciplines need to be taught and research conducted in the context of their dynamic relationships with each other and with societal problems. They cannot be perceived as protected silos of specialized knowledge anymore, if the university wants to move towards transdisciplinarity. Only fluency across disciplinary boundaries will provide clear views of the world and what needs to be done to ameliorate humanity’s pressing problems. This fluency emerges through well-thought out opportunities for cross-collaborative work.

ASU actually used the term working at the seams when it referred to inter-departmental/interdisciplinary partnerships and joint problem solving. It purposely developed new research centers and institutions and positioned them as the place where translational research occurs (they did not use the word transdisciplinary). Industry and community stakeholders meet up with academics at these centers, which serve as the incubators for innovation and new knowledge generation. The resultant translational research is readily applicable to the stakeholders involved in the research (faculty members, communities or industry). ASU referred to this as use-inspired research, evolving at the seams. Their concept actually mirrors, perfectly, the quantum physics concept of working in the vacuum between entities (see later reference to discontinuity). The vacuum is not empty but full of possibilities (McGregor, 2011).

Faculty Members

Taking lessons from ASU, faculty to be hired to do transdisciplinary work will be interdependent minded, valuing connections among and beyond the academy that are needed to solve society’s problems. They are able to conceptually work across disciplines (not just bring disciplinary-specific information to the table). They strive to fuse perspectives to generate new knowledge. This is a far cry from hiring disciplinary specialists who will work within one department, alone or with fellow disciplinarians. Interdependent minded faculty members can hold cross-department split appointments as well as concurrent appointments in any onsite research centers, think tanks or institutes.

To facilitate transdisciplinary work, employers can take concrete steps to partner existing faculty (disciplinary or transdisciplinary predisposed) with new hires. ASU now strives to create more schools, research centers and institutes using existing faculty instead of new hires, because more and more existing faculty have already bought into transdisciplinary thinking. This organizational approach is driven by the belief that transdisciplinary work entails a fused way of looking at social problems leading to an amalgamation of disciplinary concepts rather than an amalgamation of disciplinary units. Even so, they also merged departments and units in order to scaffold the merging of concepts.

Several people we spoke to explained in detail the steps they took to convince fellow academics of the merits of a transdisciplinary approach. They employed a combination of scenario building, workshops, roundtables, retreats, orientation seminars, theory building, theme building, case studies, joint teaching, mentoring, the dialogic processes and the polarity fixed concept. They were striving for the necessary attitude shifts inherent in changing paradigms. They wanted people to want to look at new ways to approach teaching, research and learning. A Mexican initiative employed, what they called, crossing savoir (learning): engaging each of practical, theoretical, artistic, popular and experiential knowledge. To cope with people’s natural resistance to change, they fostered an atmosphere of tolerance, openness, understanding and respect. They observed, during their orientation sessions, that transdisciplinarity is an exploration of how knowledge is going on in people and that the resultant knowledge is embodied (a part of everyone involved in its creation).

Inherent in transdisciplinary work is being able to communicate with each other. Several of those we interviewed spoke directly to the issue of finding a common language so people can talk to each other. This entails more than finding the right words. It requires empathy, the ability to see the world though the lens of others and then act from those insights. Both Austria and Australia spoke directly to this issue. Transdisciplinary projects must provide space to grow people’s capacity to communicate across boundaries. A project in Australia involved academics spending a year talking together regularly, trying to develop some common language and common ideas. Instead of focusing on the problem, they chose to focus on their different disciplinary research interests. They ran out of funding before they could reach out to the community, and start to understand their research needs. True transdisciplinary work entails bringing together the community perspective with disciplinary perspectives (noted above, ideally an amalgamation of concepts), through dialogue.

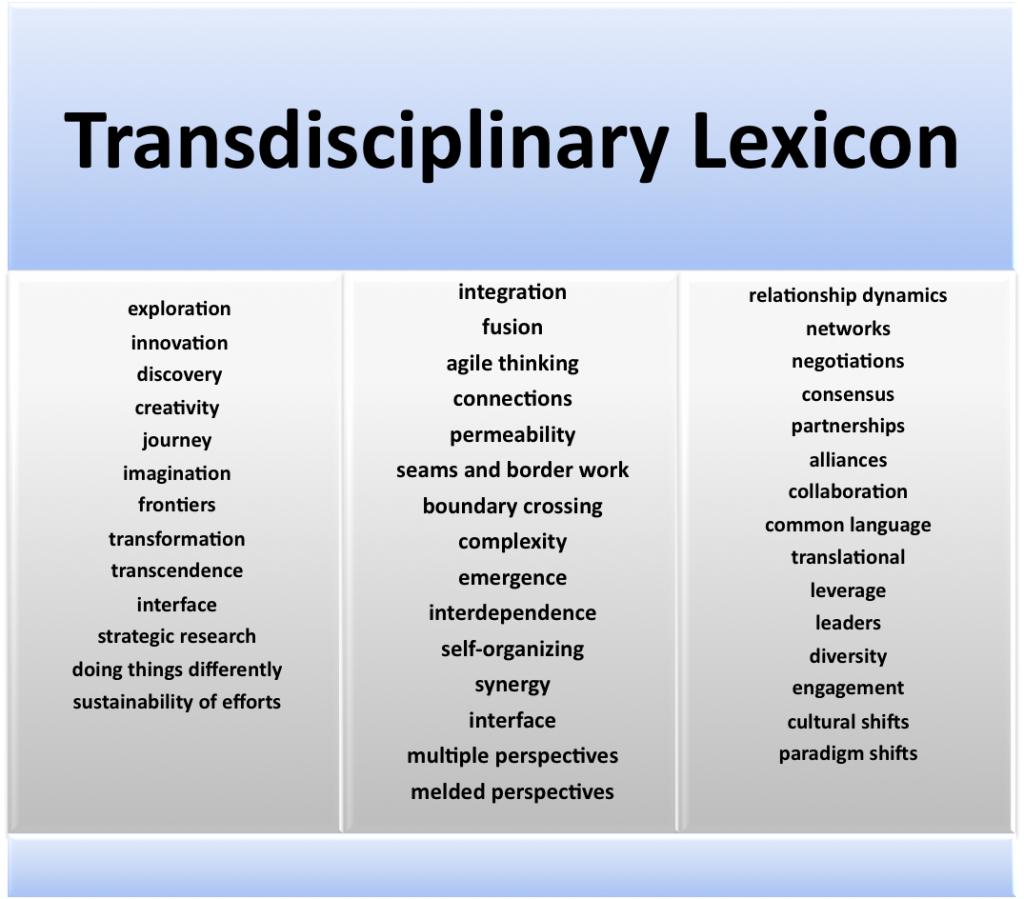

Figure 1

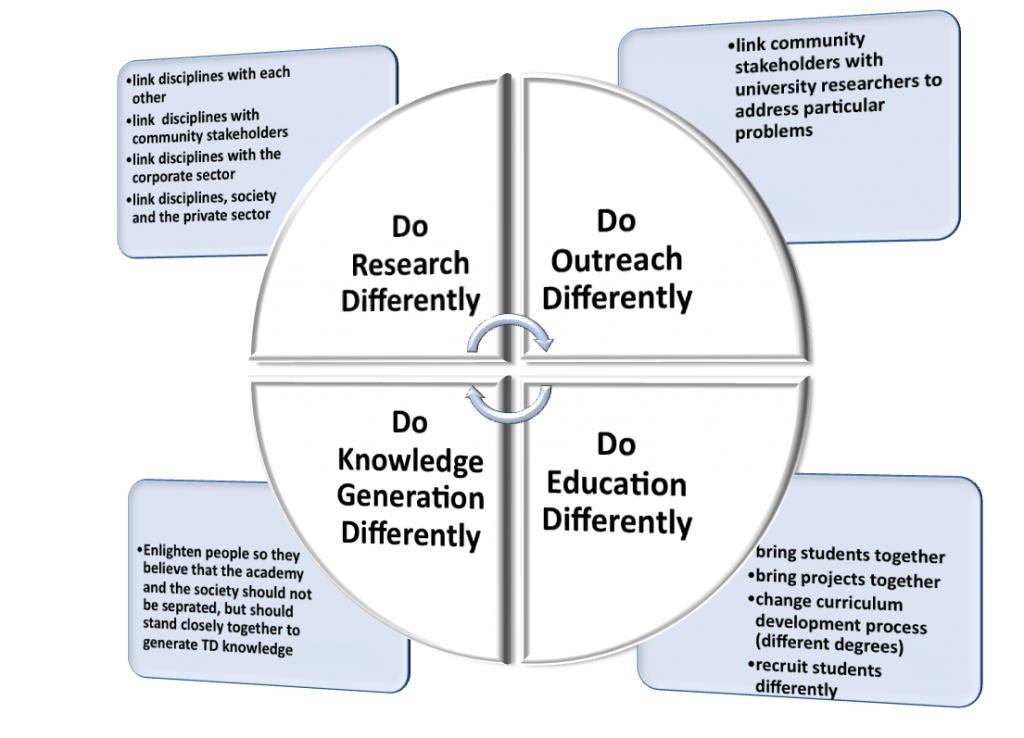

Several people we talked with also shared other insights into transdisciplinary work. First, people have to anticipate that there will be a variety of outcomes rather than one right outcome. Second, each outcome will resonate more or less with different actors involved in the process (academics, students, community members, corporations). Third, people must be prepared to accept that their perspective may have to be overshadowed in order to solve this particular social problem. Fourth, we observed, from our iterative readings of the collection of articles in this series, a transdisciplinary-specific lexicon (see Figure 1) used in various degrees by most people engaged in various approaches to this work (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Transdisciplinary Synopsis

From a more pragmatic vantage point, faculty being asked to consider transdisciplinary work often were concerned with its impact on their career path and promotion opportunities. Faculty need to feel confident that they can engage in transdisciplinary research activities and still be assured of building a credible set of publications for career advancement. Fortunately, there is an increasing number of transdisciplinary journals, many available online, through open source, Google Scholar and the like, making their work both refereed and accessible to a multi-disciplinary audience and to the lay public. As well, fellow scholars (those adjudicating promotion files) need to be sensitized to the academic rigor of these venues so they can recognize them as legitimate.

Inherent to this issue is the necessity of advocating for changes to the reappointment, tenure and promotion (RTP) process, currently predicated on disciplinary standards. Universities will have to be open to forming multiple-discipline review committees who can appreciate the nature of transdisciplinary work and value it as a legitimate mode of scholarship and knowledge generation. As well, given that most RTP processes recognize research, teaching and service, transdisciplinary work also enriches the latter two because it often involves interdisciplinary team teaching and service to the larger community through transdisciplinary scholarship.

Finally, funding transdisciplinary work has to entail obtaining grants that span disciplines (even national boundaries) and that enable scholars to partner with non-academic sectors. Several people we interviewed commented on the tensions inherent in traditionally procuring funding from industry and corporate sponsors. It will be necessary to help people rethink the university’s traditional arms-length relationship with industry and the private sector. Joining with industry to solve a complex, wicked problem is not the same thing as receiving monies from industry for product research and development (R&D). A transdisciplinary university would not be seen as selling out to industry; rather, it would be seen as partnered with industry to solve complex world problems.

Almost half of the initiatives we explored relied heavily on corporate funding, but were comfortable with this arrangement because they were working together on complex social problems that impacted both industry and society. BOKU admitted that people often assume there is a values divide between the university culture and that of companies and that this divide needs to be explored when considering transdisciplinary work. Notwithstanding, there must be constant funding of TD work including seed and development monies, implementation funding and funding to sustain ongoing and evolving work.

Students

From a transdisciplinary stance, universities would focus on what kind of student it wants to graduate rather than what kind of student it wants to take in (the latter usually predicated on socio-economic demographics and/or grade point average). When recruiting students, the university would therefore assume future students have an innate intellectual potential to engage in transdisciplinary work. Assuming that students come to the university with a built-in predisposition for something, instead of assuming they arrive with missing skill sets, is a huge paradigm shift. Innate means someone is born into something. Assuming that each applicant is born with the ability to take up transdisciplinary scholarship is a powerful and meaningful stance for a university to take. Continuing this line of thinking, assuming they can cross disciplines in order to learn, the university has to scaffold students’ learning experiences by providing opportunities to work across disciplines (including learning from faculty from a collection of departments and working with fellow students from other departments/disciplines on joint projects).

The Nature of Leadership Required for Transdisciplinary Higher Education

The process of engaging people in the transdisciplinary university project is deeply predicated on the leadership within the university system. Leadership comprises two words, leader and ship. The latter is Old English scip, a state or a condition of being. Lead is Old English liðan, to travel or to guide (Harper, 2010). Leaders are people who are most successful in guiding people to travel along a particular path; they are principal players in the game or the journey of change.

The President of ASU (Michael Crow) posed the following questions of potential leaders of the new university, intended to be part of their soul searching about the role of higher education in the 21st century: (a) what is the link between science [a.k.a., the academy] and society, (b) what is the role of science and the humanities, (c) what is the appropriate university structure for participating in the solution of 21st century human problems, and (d) what is the role of transdisciplinarity?

Michael Crow went further and challenged university leaders who are interested in moving towards transdisciplinarity to apply eight new university design aspirations. When taken together, these design aspirations comprise a new paradigm for higher education institutions. Amongst his vision for how to design a new university are: (a) pursue a culture of knowledge entrepreneurship committed to discovery, creativity and innovation; (b) transcend disciplinary limitations in pursuit of intellectual fusion; (c) embed the university in society and directly engage in the life of society; and, (d) conduct use-inspired research. He advocated that leaders apply his eight design elements to the university’s infrastructure, research and curricula (teaching and learning).

Some people in our series believed that an entire university cannot do transdisciplinarity yet; most universities are still too grounded in disciplinary practices (with a trend towards interdisciplinarity). The people we interviewed found it constructive to describe the university as a place that is becoming (reflective of the TD concept of emergence). All agreed that the potential for becoming a TD university is there if change is facilitated, not only by leaders at the top of the university infrastructure but also at the faculty, school and departmental levels (even at the administrative, human resources, custodial and clerical levels). Moreover, a mix of leaders may be required to ensure that TD is initiated, implemented and sustained; this rather than assuming that leadership will be top-down.

Those interviewed spoke often and broadly about leadership for change. They agreed that leadership is a necessary condition for the transformation of the higher education system towards transdisciplinarity. The following text represents their collective lived experiences with, and visions of, the type of leadership required to move a university towards transdisciplinarity:

- Those in leadership positions must be open to new paradigms and be willing and able to let the old paradigm go by the wayside.

- Transdisciplinary leaders in higher education must believe that the systems and institutions of higher education can be leveraged for more holistic and integrated approaches to learning, research and community engagement; the latter leads to deeper and more socially robust knowledge.

- Complex change such as this requires that the academy allow leaders to emerge in many parts of the system, people who have the wherewithal and knowledge to leverage small parts of the system to effect far-reaching, systemic change within the university’s systems and processes.

- Leaders must encourage, motivate facilitate and direct others in the university system; that is, point them in a particular direction, in this case towards a TD perspective, especially in the early stages of the change process.

- People in leadership positions (top down and emergent, bottom up) must learn to appreciate that they no longer have to protect the disciplinary core; rather, they have to become instrumental in integrating disciplines, research paradigms and personalities.

- Leaders must encourage people to think in an agile manner (quick witted, nimbly, and shrewdly) so they can create new programs for the university rather than programs that belong to one department or unit.

- Leaders must appreciate that the above integration requires finesse (subtle, delicately complex skills in handling people or situations). They must employ this finesse while creating a culture where everyone feels valued, listened to and respected; moreover, these leaders will not expect this to happen all at once. They will experience eddies, currents and diffusion over time as a TD culture strives to emerge.

- Leaders must become skilled at reaching across disciplines, forming networks and reforming these networks as needs arise. They must be open to transcending all sorts of borders and to being able to work on the frontier of knowledge (at the border of what is known and what is not known or is unknowable).

- To be truly transdisciplinary, university leaders (top down and bottom up) must actively strive to integrate non-academic actors into the university system, again working at the border between the university and society (civil and corporate).

- Rather than assuming the university is a repository of disciplinary knowledge, TD leaders must envision it as a think tank or a thinking lab where people can nurture transdisciplinary thinking and explore how transdisciplinary research can work in practice – in the real world.

- Leaders at an emergent transdisciplinary university must help people rethink the university’s traditional arms-length relationship with industry and the private sector.

- Joining with industry to solve a complex, wicked problem is not the same thing as receiving monies from industry for product research and development (R&D). A transdisciplinary university would not be seen as selling out to industry; rather, it would be partnered with industry to solve complex world problems. Nevertheless, both the university and industry (as well as other stakeholders such as community and government) will still need to address approaches for determining ownership of the products of research and their application. It is also worth pointing out that since the focus is on working with complex, wicked problems that of primary concern is action to ameliorate these problems while causing no harm.

And, it goes without saying, that leaders at a transdisciplinary university must be creative and innovative in their efforts to secure sustainable funding and resourcing for TD-related research and knowledge generation. Monies and resources will be required for: (a) instigating TD-related change in the university; (b) implementing projects, innovations and research initiatives; and, (c) sustaining the transdisciplinary arrangements, outcomes, networks and energies that emerge.

The Politics of Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education

With any change to an existing system, politics comes into play. This one word, politics, conveys layers and layers of intense, complex interactions. Politics refers to activities aimed at gaining power and status or improving one’s position or standing within an organization and within personal relationships. Politics involves social relations within group interactions in order to gain authority (the right to give orders), power and influence over decision making processes and outcomes, or both. Politics was one of the least explicitly articulated aspects of transdisciplinarity in higher education, but evident nonetheless. We take responsibility for the following discussion because we extrapolated ideas from the series that intimated politics.

In some instances, people took advantage of what they called power vacuums in which disciplines that usually hold sway did not at that point in time—the timing was right. At other institutions, people orchestrated a strategic approach, bringing faculty on board before going to the administration with their proposal for a transdisciplinary approach. Some drew on their societal context, making the case that transdisciplinarity was the most appropriate response from their university. Others started small, exercising influence in their own particular arena, using their initiative as a case study of the merit of transdisciplinarity for the university as whole. Still others had leadership from the top down consciously reorienting the entire university to a different approach. Some efforts focused on educating students via new degree programs while others focused on reorienting faculty members’ approaches to conducting research. These all involved different politics. We assume that transdisciplinary politics looks like all of this, and more.

As well, our series was biased in that we managed to approach people engaged with successful initiatives to bring transdisciplinarity to their university in some shape or form. Stories from those who have tried and failed or who are revisiting their original play for power would be very beneficial. Some people in our series ran out of money before they could capitalize on the energies emergent from their efforts to engage in TD work. Some had not yet engaged with the tensions inherent in universities partnering with industry. Others were calling for transnational conversations about curriculum policy in higher education but the initiative was too recent to report results. Some struggled with working together to find a common language so they could fuse disciplinary concepts with community perspectives. Others were eager to create post-graduate studies to augment their new undergraduate programs. There are always the issues of how to respectfully engage communities in university-coordinated course work for which students gain academic credit, or how to work with industry without the appearance, or reality, of being co-opted.

Emergent Conclusions

Our analysis of the TD series did not reveal a model approach to bringing transdisciplinarity to higher education. We discovered a wide range of reasons for why it needs to be done, how that should happen (approaches, strategies and messaging), what type of leadership is required and the politics of getting the job done. We will close with a quote from Ana Cecilia Espinosa Martinez from the Universidad Arkos (Mexico), who drew on the quantum physics concept of discontinuity. This holds that moving from one place to another does not require the boundaries to actually touch; instead, people move across a vacuum to get from one point to another. There is discontinuity (a gap) between people. Transdisciplinarity work happens in this gap. The vacuum is not empty; it is full of emergent potentialities.

Because people tend not to be aware of the gap, they resist what happens to them when they actually enter it (McGregor, 2011), a resistance that explains many of the nuances of trying to bring transdisciplinarity in higher education (why it is so hard to achieve but so worth the effort). Bridging this gap is the challenge universities face in the 21st century if the fabric of universities is to reflect the fabric of society, the complex weave of problems facing humanity. Transdisciplinarity is one way to bridge the gap:

Transdisciplinarity is not an evolutionary process in the sense of a linear accumulative line that goes up. It is a process that is discontinuous. This discontinuous process involves resistance, opening, tolerance, change, and so on. It’s not that we have resistance at the beginning and will not have it anymore. No, the people have moments of resistance at several times during the process. But, most of all, [through transdisciplinary work,] we see changes in people’s thinking processes and attitudes toward a more integral and complex view of reality of human praxis in the world and on what a university’s purpose is [in that world].

References

Harper, D. (2010). Online etymology dictionary. Lancaster, PA. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com/index.php

McGregor, S. L. T. (2007). Consumer scholarship and transdisciplinarity. International Journal of Consumer Studies,31(5), 487-495.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2011). Demystifying transdisciplinary ontology. Integral Leadership Review, 11(2), http://integralleadershipreview.com/2011/03/demystifying-transdisciplinary-ontology-multiple-levels-of-reality-and-the-hidden-third/

About the Authors

Professor Sue LT McGregor, PhD is a Canadian home economist and Doctoral Program Coordinator in the Faculty of Education, Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Prior to that, she was a member of the Human Ecology Department for 15 years. Sue’s work explores and pushes the boundaries of consumer studies and home economics philosophy and leadership, especially from transdisciplinary, transformative, new sciences, and moral imperatives. In 2010, she was appointed Docent in Home Econom- ics at the University of Helsinki. She is a member of the IFHE Research Committee, a Kappa Omicron Nu Research Fellow, a Sustainable Frontier Research Associate, and a long-time Board member of the International Journal of Consumer Studies. She has delivered over 35 keynotes/invited talks in 10 countries, has over 120 peer-reviewed publications, 11 book chapters, and six monographs. She published Transformative Practice (2006) and her new book, Consumer Moral Leadership, was released in May 2010 (Sense Publishers). She received the 2009 TOPACE international award for her work on transdisciplinary consumer/citizenship education. She is the Principal Consultant for The McGregor Consulting Group (founded in 1991). http://www.consult mcgregor.com/ Email: sue.mcgregor@msvu.ca

Russ Volckmann, PhD, is Publisher and Editor of Integral Leadership Review and Integral Publishers, LLC.

Dear Colleagues,

We are a research group about transdisciplinarity educació that we apply this methodology in the first year of degree Science of Education, in a large aplitud subject credit bringing together studies on Society, Science and Culture.

We wanted to record to update its list at your discretion in a future: “Table 1: Surveyed Programs”.

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Ciències de l’Educació. Barcelona, Spain.

(Education Research Group transdisciplinary GRET)

Sincerely,

Jaume Barrera