Mark McCaslin

The Integral Leadership Review is the world’s premier publication of integrated approaches to leading and leadership. It is a bridging publication that links authors and readers across cultures around the world. It serves leaders, professionals and academics engaged in the practice, development and theory of leadership. It bridges multiple perspectives by drawing on integral, transdisciplinary, complexity and developmental frameworks. These bridges are intended to assist all who read the Integral Leadership Review to develop and implement comprehensive shifts in strategies by providing lessons from experience, insights, and tools all can use in addressing the challenges facing the world. http://integralleadershipreview.com/

Community of Scholarship

The Integral Leadership Review invites you to join our Community of Scholarship. It is the purpose of this community to disseminate peer-reviewed articles concerning the theories, relationships, applications, and educational practices surrounding integral leadership. There are multiple ways to participate from engaging in discussions surrounding published articles written by integral leadership scholars and practitioners to offering your own manuscript for consideration in our new peer reviewed section. We also seeking individuals who would wish to serve as reviewers of submitted manuscripts.

FORMAT

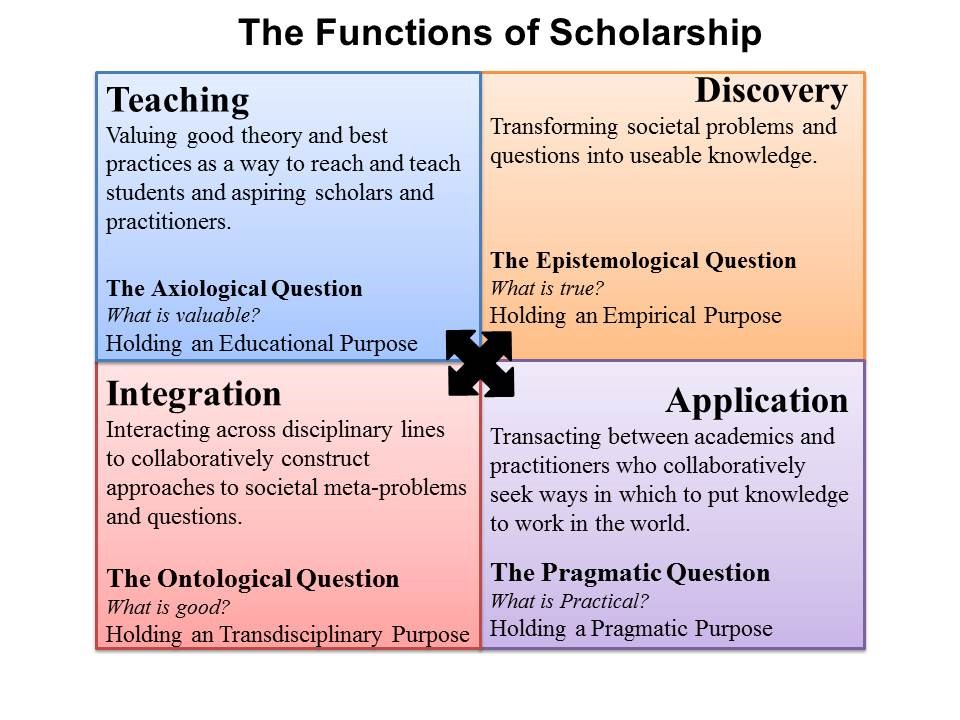

In order to create a generative and integral synthesis concerning the natures of integral leadership, fittingly made possible by this community of scholarship, it is essential that our invitation is open to all elements of scholarship. According to Boyer’s model there are four distinct but overlapping functions of scholarship: discovery, integration (sometimes referred to as engagement), application and teaching. Scholarship, within this model, is not just a linear cause-and-effect relationship that moves from research, to publication, to application to teaching. The Boyer model challenges this currently held assumption: “The arrow of causality can, and frequently does, point in both directions. Theory surely leads to practice. But practice also leads to theory. Teaching, at its best, shapes both research and practice” (citation).

An integral approach to the four functions of scholarship holds the utility of drawing an interconnected whole when it comes to discovery, engagement, application, and teaching. Authors are encouraged to “reach across” using the full efficacy of these functions with the purpose of inviting dialogue among integral thinkers. Integral thinking draws together the functions of scholarship into an interrelated system of ideas that are mutually enriching (Volckmann, 2014). Integral thinking can be seen as synergistic as it relates to the functions of scholarships as it seeks a synthesis of these approaches and perspectives (Esbjőrn-Hargens, 2010). Figure 1 is a simple representation of this integral thinking. The functions of scholarship in this model form an interrelated dynamic with each contributing and acting on the other. As such valuing, interacting, transacting and transforming enliven and inform the whole. The dynamic is not linear but networked. In the end the lines separating individual realms dissipate forming a community of scholarship.

Areas for Submission

Teaching

The hallmark of the community of truth is not psychological intimacy or political civility or pragmatic accountability, though it does not exclude these virtues. This model of community reaches deeper, into ontology and epistemology – into assumptions about the nature of reality and how we know it – on which all education is built. The hallmark of the community of truth is in its claim that reality is a web of communal relationships, and we can know reality only by being in community with it.

~Parker Palmer

This element of scholarship recognizes the work that goes into mastery of knowledge as well as the presentation of information so that others might understand it. “Teaching, at its best, means not only transmitting knowledge, but transforming and extending it as well” – and by interacting with students, teachers and trainers are pushed in creative new directions. Teaching therefore becomes the act and the art of delivering valuable knowledge to the world.

The valuing approach to the scholarship of teaching enlivens creativity and deepens our ability to engage in creative discussions about teaching and learning on multiple levels. We can, through this approach, hold multiple perspectives concerning the art and science of teaching to include the effective delivery of content, modelling the ways of being, cultivating ways of thinking, facilitating self-efficacy, and seeking a better society (Pratt, 1998).

These integral scholars and practitioners ask:

How can knowledge best be transmitted to others and best learned?

How can knowledge best be modeled or engaged for others and best learned?

How can knowledge best be used to cultivate critical and creative thinking?

How can knowledge best be used to generate a sense of high self-efficacy?

How can knowledge best be used to create an engaged citizenry?

Integration

Disciplines, like nations, are a necessary evil that enable human beings of bounded rationality to simplify the structure of their goals. But parochialism is everywhere, and the world sorely needs international and interdisciplinary travelers who will carry new knowledge from one enclave to another.

~Herbert Simon (Nobel Laureate, 1992)

This element of scholarship, sometimes called the scholarship of engagement, is what happens when scholars put isolated facts into perspective, “making connections across the disciplines, placing the specialties in larger context, illuminating data in a revealing way”. This is scholarship that “seeks to interpret, draw together, and bring new insight to bear on original research”. Closely related to discovery, integration draws connections at the intersection of processes, philosophies, and disciplines, examining the contexts of these intersections in a transdisciplinary and interpretive way.

Interacting across disciplinary lines in order to collaboratively construct approaches to societal meta-problems and questions is at the heart of the scholarship of integration. Transdisciplinarity concerns itself with the transgression of artificially constructed discipline-based boundaries allowing our collective intelligences to approach and solve the big problems we face thereby granting an address to the real issues of concern for the scholarship of integration—capacity building, creating sustainable systems, and generativity. “Transdisciplinary research practices are issues – or problem-centered and prioritize the problem at the center of research over discipline-specific concerns, theories or methods”. (Leavy, 2011, p.9)

These integral scholars and practitioners understand that new knowledge and ways of understanding knowledge in new ways are often discovered at the intersections of disciplines. These scholars and practitioners ask:

What do the findings mean?

What is being left out of this approach or design?

What are we missing?

What perspectives are not being considered?

Is it possible to interpret what’s been discovered in ways that provide a larger, more comprehensive understanding?”

The scholarship of integration is an orientation to scholarship that interprets and engages knowledge across and between disciplines. It purposes itself with explicating researchable problems using relevant bodies of disciplinary knowledge, to include the combination of methods/techniques/theories, in order to address meta-questions that form at the intersection of two or more disciplines.

Application

What you want is a philosophy that will not only exercise your powers of intellectual abstraction, but that will make some positive connexion with this actual world of finite human lives. You want a system that will combine both things, the scientific loyalty to facts and willingness to take account of them, the spirit of adaptation and accommodation.

~William James (1907)

This element of scholarship is the most practical in that it seeks out ways in which knowledge can solve problems and serve both the community and the campus. As opposed to merely “citizenship,” Boyer argues that “to be considered scholarship, service activities must be tied directly to one’s special field of knowledge and relate to, and flow directly out of, this professional activity”. He importantly notes that knowledge is not necessarily first “discovered” and then later “applied” – “new intellectual understandings,” Boyer writes, “can arise out of the very act of application…theory and practice vitally interacts and one renews the other”. This element reveals another two-way conduit on which what is known and/or could become known travels. Therefore, within the scholarship of application, theory and practice are in the state of transacting.

Transactivity can be seen as a pragmatic method that dissolves the polarity between the subjective and the objective into a more primordial, original situation of understanding, characterized instead by a spaciously creative and practical structure (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2000). Transactivity concerns the revelation of something hidden, some greater whole, rather than the correspondence between subjective thinking and the objective reality. The ultimate goal of this aspect of this approach to scholarship is to seek ways in which to put knowledge and/or wisdom to work in the world for the betterment of all.

These scholars and practitioners ask:

How can knowledge be responsibly applied to problems?

How can knowledge be helpful to people and institutions?

How does effective practice inform (challenge/change/extend) existing theory?

The scholarship of application holds a two-fold purpose:

- To provide practitioners with theoretical support in addressing real problems through the articulation of practical/useable solutions.

- To inform theory through an explication of best practices in the field.

Discovery

Wisdom begins with wonder.

~Socrates

Science is organized knowledge.

Wisdom is organized life.

~Immanuel Kant

At the core of the scholarship of discovery according to Boyer (1990) is “what contributes not only to the stock of human knowledge but also to the intellectual climate of a college or university” and Boyer considers investigation and research to be “at the very heart of academic life”. “Not just outcomes, but the process” gives research design and methodologies a critical role. These are the disciplined and investigative aspects of scholarship. Present in the formation and foundations of the scholarship of discovery are the critical substrates of creativity, wonder and wisdom. The scholarship of discovery is not devoid of these catalysts but informed by them. Their presence permits the formation of bridges, connections, to the other realms of scholarship by way of transforming societal problems and questions to useable knowledge through the use of the scientific method. Moreover, discovery, through the construction methodological inventions and approaches, develops tools for discerning and encountering what has yet to be found.

These scholars and practitioners ask:

What is to be known?

What is yet to be found?

How do we approach it? (Research design)

What tools do we need have or create to find it? (Research methods)

The purpose of discovery within the realms of scholarship is to discern and disseminate new knowledge or to extend existing knowledge in new ways through what is called “traditional research.” Using qualitative and quantitative approaches as well as blended designs and mixed-methods, covering idiographic and nomothetic aspects surrounding projects that seek to understand, explain, predict or control an identified research problem.

Lincoln and Guba (1985) define researchable problem as “two or more factors” (p.226) in a mutual shaping relationship “that yield a perplexing or enigmatic state (a conceptual problem), a conflict that renders a choice from among alternative courses of action moot (an action problem), or an undesirable consequence (a value problem)” (p. 226). These different types of problems correspond directly to the philosophical/theoretical/conceptual framework of the study in that philosophical frameworks most often yield value problems, theoretical frameworks yield action problems, and conceptual frameworks yield conceptual problems. The use of the extant literature then is used to support these various frameworks and to identify contributive potentials of the study (i.e. the significance of the study). Keep in mind:

The conceptual problem asks – “Why is this situation the way it is?”

The action problem asks – “Which course of action would be moot?”

The value problem asks – “What is desirable?”

Manuscript Submission Guidelines:

It is our policy not to decline to review any manuscript submitted solely of the basis of format. To that point our reviewers will offer thoughtful and often thought provoking responses and critiques on manuscripts submitted for review. Our goal is support emerging ideas and practices surrounding integral leadership through their direct dissemination. Final versions of papers will follow APA 6th Ed. Guidelines.

INITIAL SUBMISSIONS

Just like other articles

REVIEW

Manuscripts receive a screening review for appropriateness by the Editor. Upon selection the editor will distribute the manuscript for comment in a blind review process. Authors will receive acknowledgement of receipt of manuscripts and will be notified within 60 days of the results of the review.

Manuscript Preparation

Manuscripts should be prepared using the APA Style Guide (Sixth Edition). All pages must be typed, double-spaced (including references, footnotes, and endnotes). Text must be in 12-point Times Roman. Block quotes may be single-spaced. Must include margins of 1inch on all the four sides and number all pages sequentially.

The manuscript should include four major sections: Title Page, Abstract, Main Body, and References.

- Title page. Please include the following:

- Full article title

- Acknowledgments and credits

- Each author’s complete name and institutional affiliation(s)

- Corresponding author (name, address, phone/fax, e-mail)

- Abstract. Print the abstract (150 to 250 words) on a separate page headed by the full article title. Omit author(s)’s names.

- Text. Begin article text on a new page headed by the full article title. Omit author(s)’s names.

- References.

All authors must provide an e-mail address to facilitate communications with ILR.

DIRECT SUBMISSION QUESTIONS TO:

Dr. Mark McCaslin

Associate Editor for Peer Review

Integral Leadership Review

mark@integralleadershipreview.com