Gerard Bruitzman

Gerard Bruitzman

God became man so that man might become God.

– Saint Athanasius, Saint Augustine, Saint Cyril of

Alexandria, Meister Eckhart, Jacob Boehme, and many

others (W Perry, 2008, p. 23)You see yourself as the drop in the ocean, but you are also the ocean in the drop.

– Rumi (online)

I have lived for nearly sixty years now. I remember the Roman Catholic Church in my early childhood before the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), when the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was, I believed, an actual sacred participation in the Divine Death and Resurrection of the Eternal Christ that had and continues to have momentous significance for the quality and destiny of each and every human soul. I remember my education in Catholic schools, which didn’t make much sense at all, with religion degenerating from open-hearted love for all creatures in God’s creation into the blind alleys of sectarian loyalty, with morality deteriorating from loving service to all beings into rigid systems of blind obedience often reinforced by cruel psycho-physical abuse and indifferent socio-ecological neglect, with science teaching evolution by natural selection regardless of any non-material factors instead of universal cosmogenesis through acts of creative love, and with tribal members of a religion or a science attacking each other and their own dissenters with as much hell as they could unleash either inside or, far too often, outside of the law. I remember my days of naïve idealism at university, when I believed our environment was going to be renewed, social justice was going to be delivered, world peace was going to be achieved, and our planet was going to become a better place for all of us and future generations, despite the considerable evidence for multiple escalating crises in our global civilization. During my journey, I have accumulated my share of biological, psychological, social and cultural (bio-psycho-socio-cultural) hits with some resultant traumas ranging in degrees of significance from surgical removal of my large intestine after decades of bowel disease to frequent periods of socio-cultural isolation at home, school, work and play, due in part to my constant wrestling with my life’s koan—who or what is true?—given to me at Kimba in South Australia, while hitchhiking from Melbourne across the Nullarbor Plain to Perth in 1975, to long periods of immobilizing depression because much of life did not make much coherent sense. Now I’m in the gradual process of coming out of another unsure period of great confusion with this current reading of our human condition that I would like to share with you, if you are interested. I hope you find this discussion useful.

In our discussion, we will locate various groups of prisoners, who accept the status quo, freedom fighters, who want to change the status quo, and light bearers, who contemplate the present dance of light and shade, within premodern, modern and postmodern times respectively. We will do this in the context of an integrative reading of three major considerations: 1) the three eyes of knowing (the eyes of body, mind and heart) that are present in the perennial philosophy, 2) the human knowledge quest in premodern, modern and postmodern times respectively, and 3) the levels of human development through childhood and adulthood towards more inclusive wisdom and heart-centered compassion. In some moments of our discussion, we will connect with the views of Huston Smith, an eminent philosopher of religion and well-versed teacher in the world’s enduring wisdom traditions and for many years a beloved friend of Ken Wilber (Wilber, 2000, p. 300), who said in a candid interview with Samuel Bendeck Sotillos (2013) in Psychology and the Perennial Philosophy, “With regards to Ken Wilber I just disagree with him; this may be close-minded of me but with all due respect to him, I do not think he has the substance to stand up and critique the perennial philosophy” (p. 89). We mention here that, if you are surprised by Smith’s strong opinion, you may need to pause for yourself and start to wonder about the factors that are contributing to the significant variances in Smith’s, Wilber’s, and other integral worldviews that are currently available. Before we proceed into this tentative attempt to provide a provisional integral vision of our global humanity through a comparative discussion of premodern, modern and postmodern times, which includes a brief inquiry into some selected issues in relation to Wilber’s (2012) Integral Theory, I pray you will forgive me for any second or third-person narrow-mindedness or dim-spiritedness on my part that is quite likely to be present in the sequel.

The Three Eyes of Knowing

I am interested in what was true in the past, what is true now, and what will be true in the future. In short, I am interested in what is timeless.

– Huston Smith (Cousineau, 2003, p. xxi).

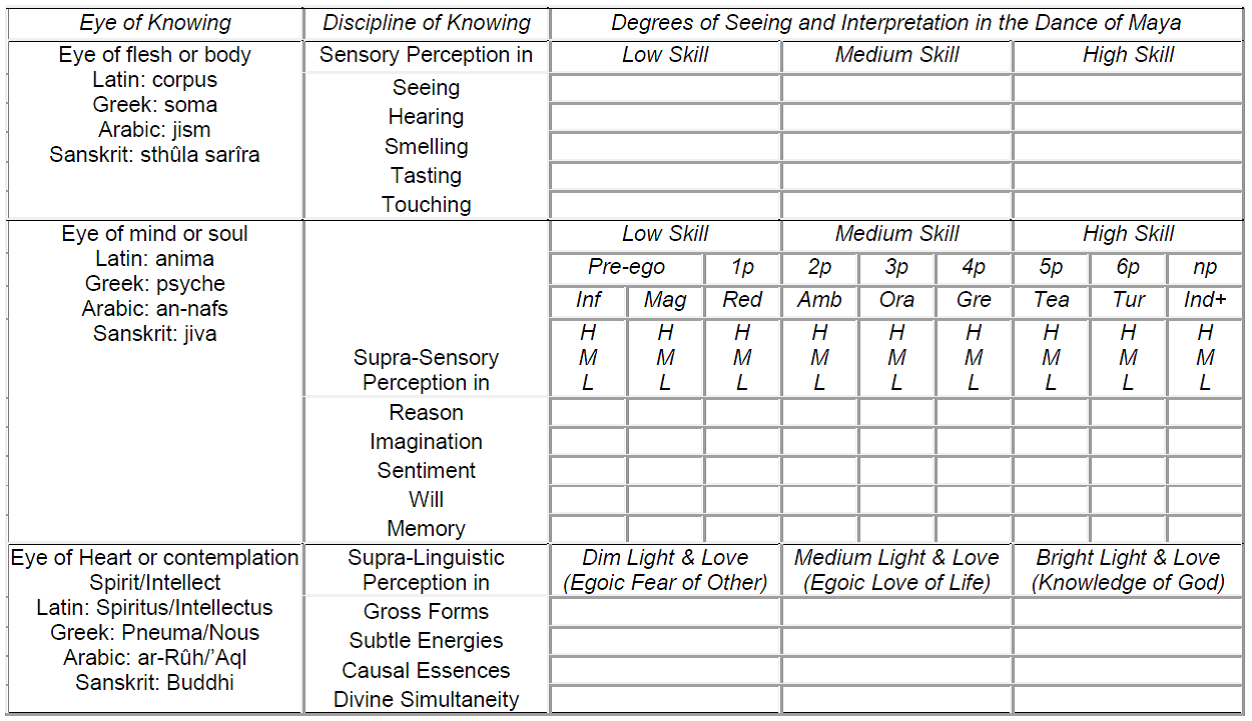

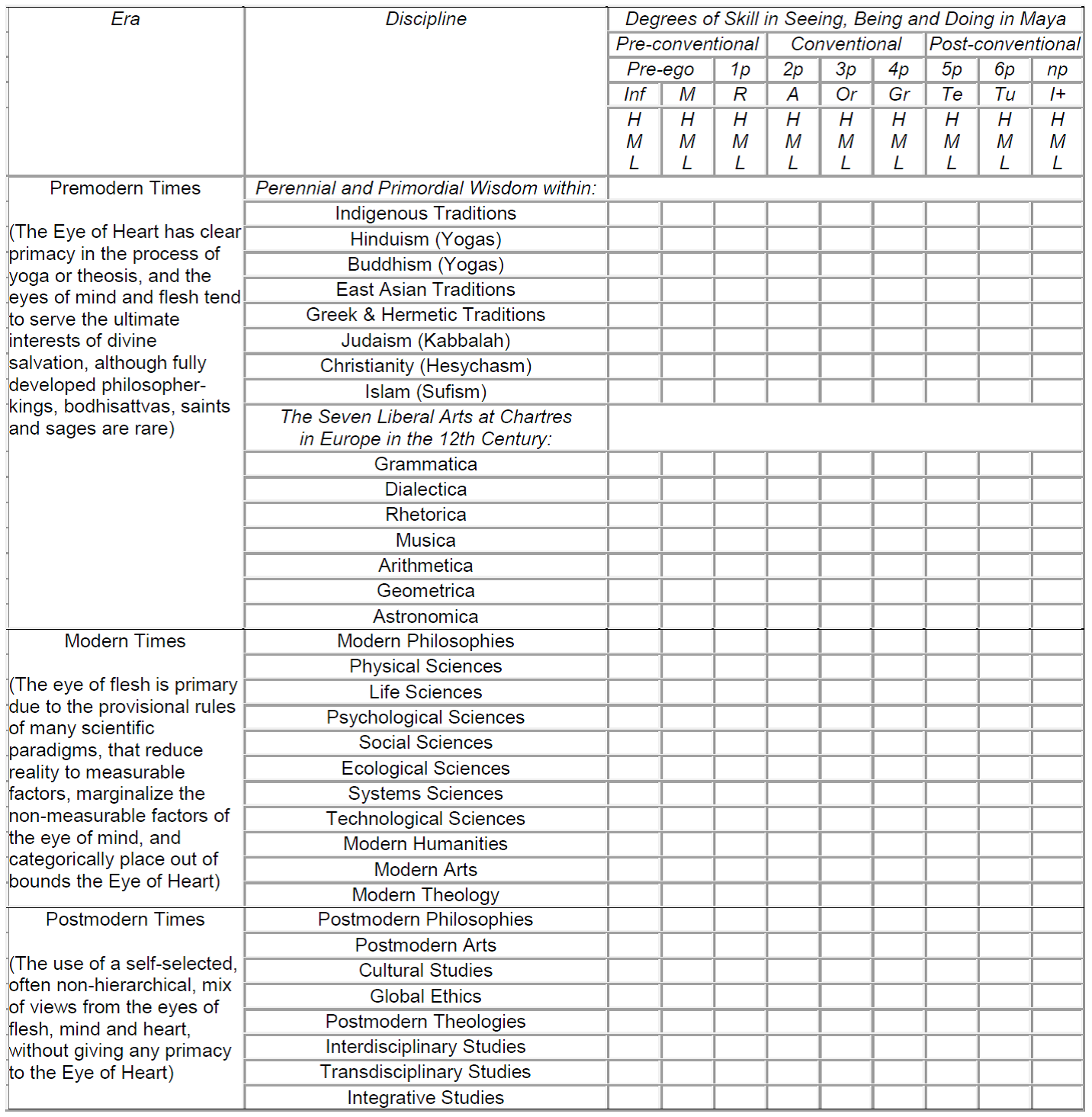

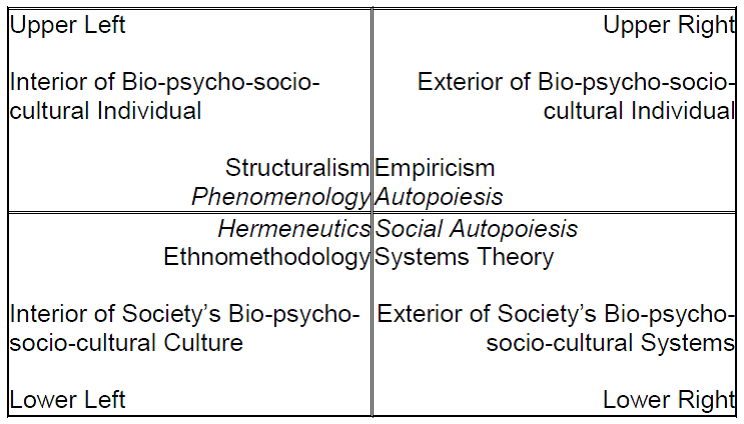

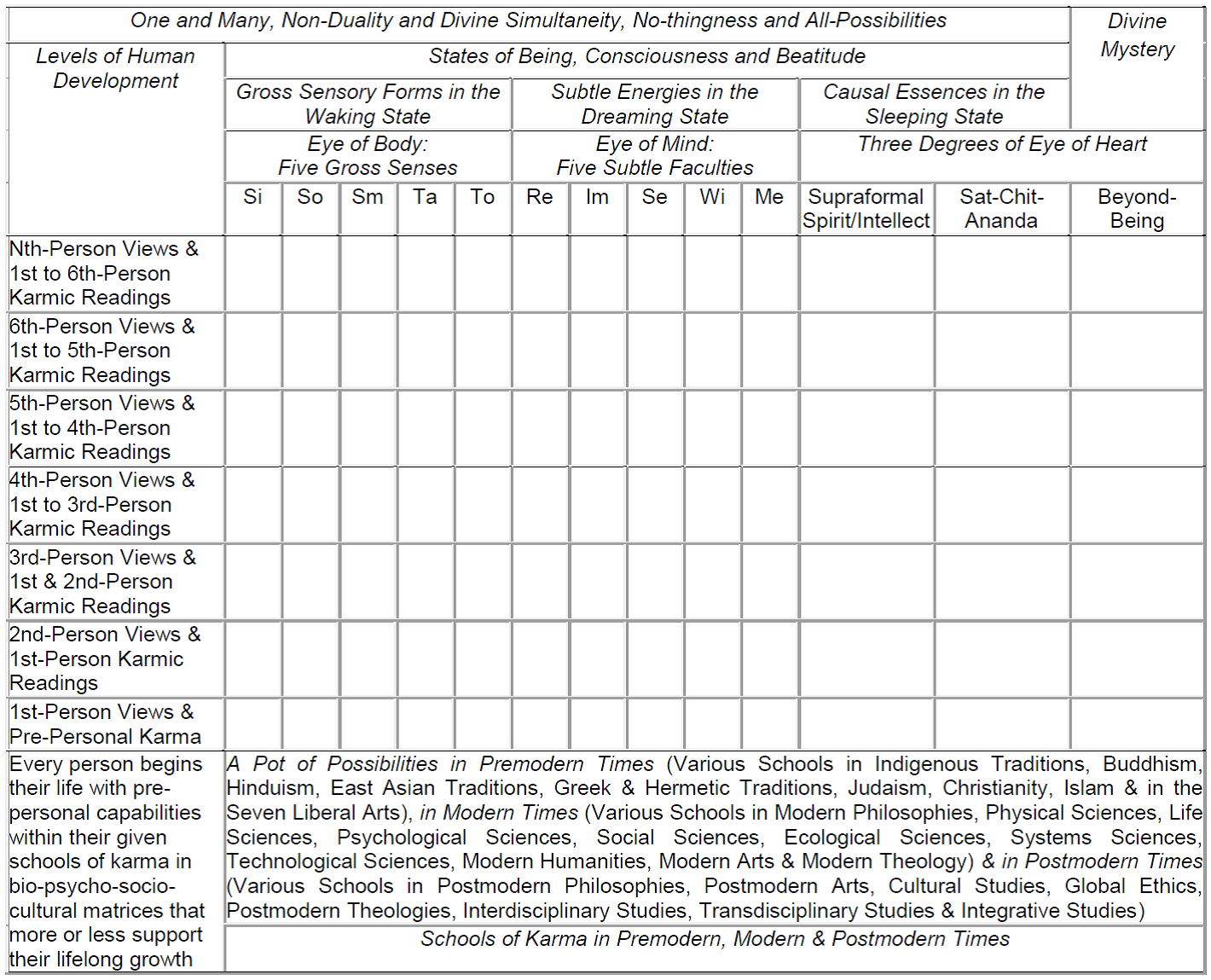

We begin our discussion by introducing the three eyes of knowing described by Wilber in phase 3 of his work in the 1980s. In his Collected Works, Vol. 3, Wilber (1999b) affirms that the eye of flesh “gives us knowledge of sense objects”; the eye of mind “gives us knowledge of philosophical truths”; and the Eye of Heart (also called the eye of contemplation) “reveals salutary truth, “truth which is unto liberation”” (p. 155). These brief accounts however need to be unpacked to some degree, as shown in table 1, to reveal some of the inherent possibilities that are present in each eye of knowing.

- Table 1. The Three Eyes of Knowing.

Sources: Adapted from Ken Wilber (1999c, 2006), William Stoddart (2012) & Samuel Bendeck Sotillos (2013).

Abbreviations: Adapting from Susanne Cook-Greuter’s (2005) ego development scale, Pre-ego = fusion with bodyself and given family worldspace, 1p = 1st-person view, 2p = 2nd-person views, 3p = 3rd-person views, 4p = 4th-person views, 5p = 5th-person views, 6p = 6th-person views, and np = nth-person views. Adapting from Ken Wilber’s (2006) altitude scale, Inf = Infra-red, Mag = Magenta, Red = Red, Amb = Amber, Ora = Orange, Gre = Green, Tea = Teal, Tur = Turquoise, and Ind+ = Indigo + further degrees of development. HML = high, medium, and low levels of skill at each degree of development.

The Eye of Flesh

The eye of flesh differentiates into five senses to access the sensory features of corporeal worlds. For many people their most important sense is seeing with their eyes, but for many others it may be hearing with their ears, or smelling with their nose, or tasting with their tongue, or touching with their skin, often depending on the bio-psycho-socio-cultural situation in which they are located.

In relation to degrees of competency in the five senses, some people live in very good bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions that provide growth appropriate supports and challenges that prompt them to train intensively each of these five senses and use them in single, plural or altogether ways up to the highest degrees of competency. Many more live in relatively good bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions that allow them to become much more skilled in one or more senses than the other senses. A few can lose one sense such as eyesight in an accident and yet become a rare expert in using the other senses such as hearing and touching, as demonstrated in the life of blind hero Jacques Lusseyran, who became a French underground resistance leader during the Second World War (Lusseyran, 2011).

When we take measurements of the various degrees of competency people may have attained in using each of their five senses, for this discussion, we can differentiate in broad terms low, medium or high degrees of skill, as indicated in table 1.

The Eye of Mind

The eye of mind differentiates into five important faculties to turn sensory and supra-sensory views into images and concepts, constructed readings and interpretations, and transmitted languages of individual and collective meaning and vision. For many people their most important faculty is reason, but for many others it could be imagination, sentiment, will, or memory, depending on the situation interwoven out of all sorts of bio-psycho-socio-cultural factors in which they are located.

Again, as in the training of each of the five senses, many people live in mostly fertile bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions that provide growth appropriate supports and challenges that prompt them to become highly competent in using one or more of the five faculties. Although some people are highly accomplished in using their five faculties altogether with ever greater degrees of integrity, more often than not many people are educated within relatively fertile bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions at home, school, work, or play that favor to a significant degree one or more faculties and neglect to some degree the other faculties. For example, a poet is probably more accomplished in using the faculties of imagination and sentiment than a scientist, who in turn is probably more accomplished in using the faculties of reason and will than the other faculties, with each of them becoming more skillful in using a different type of memory.

Again, as in measuring degrees of skill in each of the five senses, we can differentiate the degrees of skill people may have attained in using each of these five faculties into the broad categories of low, medium or high skill levels. For more sensitive measurements, we can differentiate degrees of skill using our modified readings of Susanne Cook-Greuter’s (2004, 2005, 2010) ego development scale into first-person, second-person, third-person, fourth-person and onto nth-person views (perspectives) or readings (interpretations); and Wilber’s (2006) color altitude scale into levels of vision and interpretation, as listed below. For additional nuance, we can differentiate low, medium or high degrees of skill within each of these degrees of skill.

- Red, first-person, ‘only I am right’ egocentric views of the senses and faculties

- Amber, second-person,‘only our group is right & responsible’ sociocentric views of the senses and faculties, include first-person readings of the senses and faculties

- Orange, third-person, systemic, ‘all humans have rights & responsibilities’ worldcentric views of the senses and faculties, include first & second-person readings of the senses and faculties

- Green, fourth-person, meta-systemic, ‘rights & responsibilities of interrelated living beings’ worldcentric views of the senses and faculties, include first to third-person readings of the senses and faculties

- Teal, fifth-person,integrating humanity and nature in planetcentric views of the senses and faculties, include first to fourth-person readings of the senses and faculties

- Turquoise, sixth-person, integrating humanity and nature in kosmoscentric views of the senses and faculties, include first to fifth-person readings of the senses and faculties

- Indigo+, nth-person, integrating nature, humanity and Divinity in all-possibility views of the senses and faculties, include first to sixth-person readings of the senses and faculties

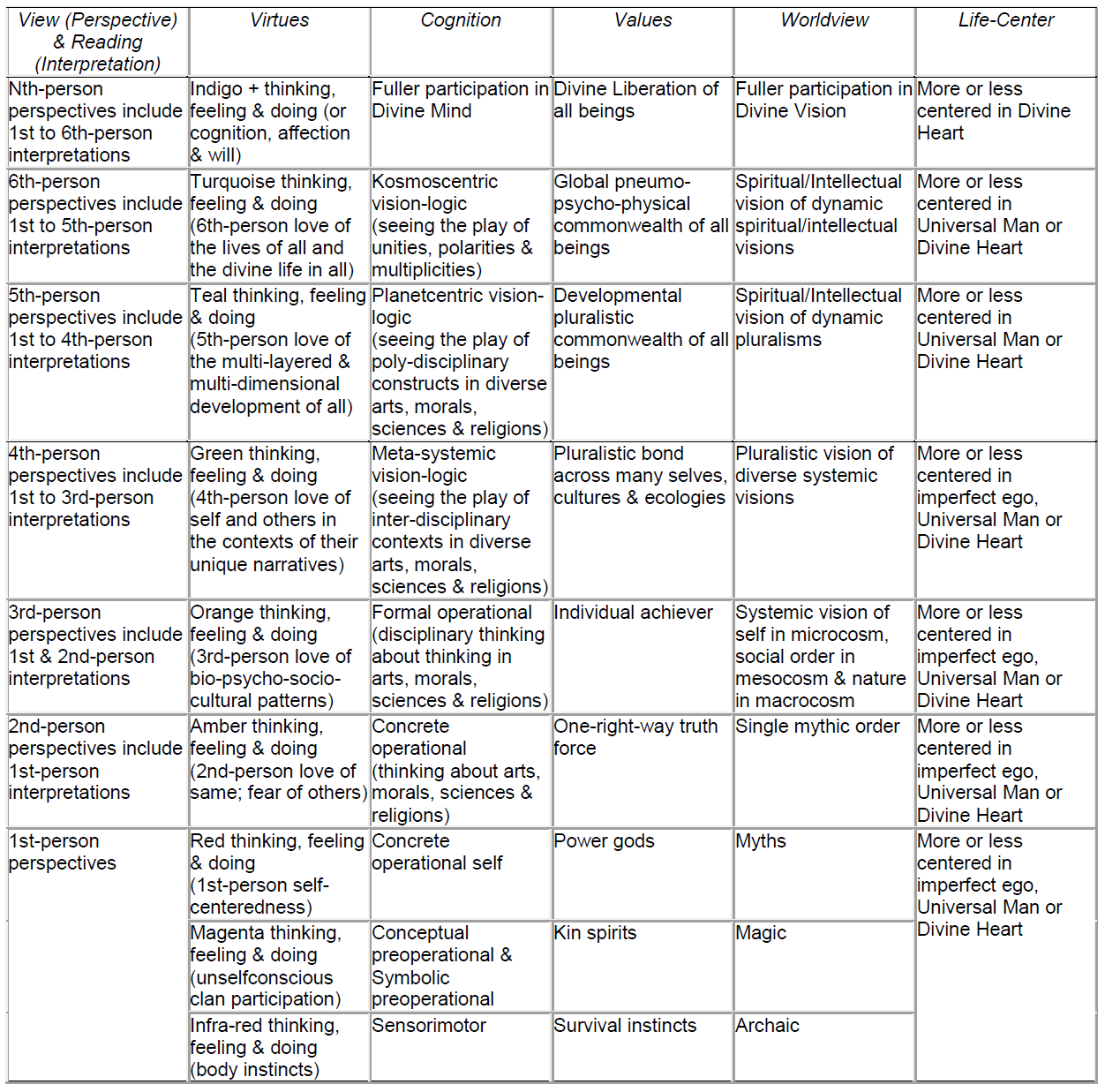

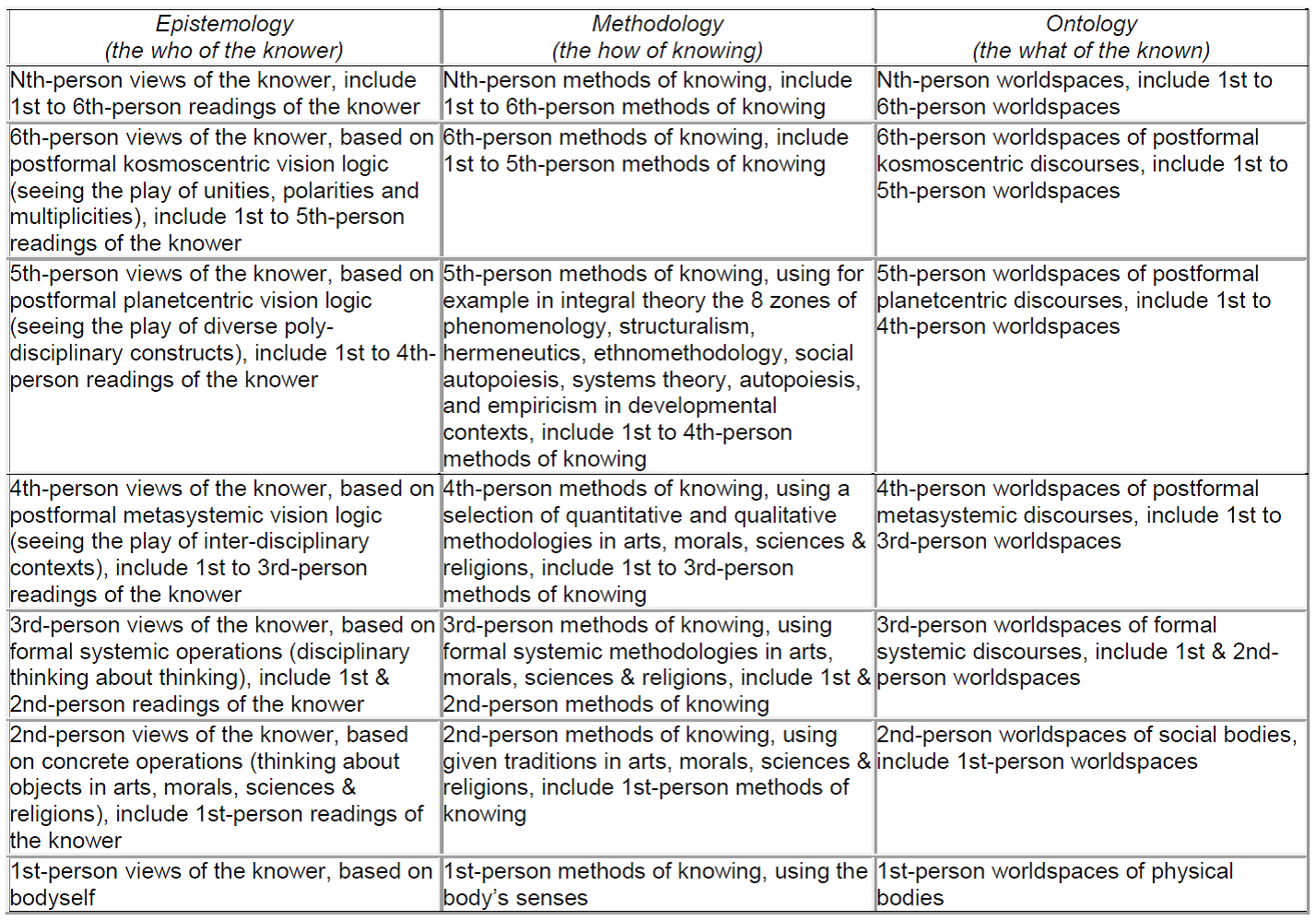

With this basic outline of degrees of skill in the ten powers (five senses plus five faculties) in place, we now add a few amendments. In table 2, we add further complexity by correlating nine different degrees of skill across altitudes of views (perspectives), virtues, cognition, values, and worldview, which you can review at your leisure. At this point we will not go any further into unpacking these somewhat speculative claims about measuring more or less developed degrees of skill in each of the ten powers that each person may develop given growth appropriate bio-psycho-socio-cultural supports and challenges during their lifetime. However we need to point out that it is very unlikely that a person will be able to maximize capability in each of their ten powers and then be able to integrate their ten fully performing powers into a fully functioning human being living in a fully functioning global society during their lifetime. Thus in this specific sense no one is a fully alive integral human being.

We digress from our brief account of the eye of mind to make three important points about the human condition in premodern, modern and postmodern times. First, the life-center column in table 2 refers to three possible ways of human functioning that are present at lower degrees of development. One way is to operate with significant degrees of freedom from bio-psycho-socio-spiritual karma in tune with the Divine Heart or Center of all things in either an impermanent samâdhi experience or a more permanent state of spiritual wakefulness. A second way is to work to redeem an imperfect ego’s bio-psycho-socio-spiritual karma in a re-membering of a Divine Exemplar known in the perennial philosophy as Universal Man (Adam Qadmôn in Kabbalah, al-Insân al-Kâmil in Sufism, Chün-Jên in Taoism, or True King-Pontiff in Christianity), who is an authentic master of body and soul in Divine Spirit (W Perry, 2008, p. 896). A third way is to act out bio-psycho-socio-spiritual karma immersed in complex individual and collective patterns of desires and fears, addictions and allergies, pleasures and pains with an imperfect ego. Needless to say that the third way of living life is prominent throughout human history, increasingly so in modern and postmodern times when the process of Divine Liberation is marginalized to a significant extent within many religious and secular worlds.

- Table 2. Levels of Vision and Interpretation of Mind in Individuals and Societies in Premodern, Modern, and Postmodern Times in Maya.

Sources: Adapted from Don Beck & Chris Cowan (1996), Ken Wilber (2006), Michael Commons & Sara Ross (2008), Terri O’Fallon (2011b, 2013) & Mark Perry (2012). Abbreviations adapted from Mark Perry (2012): Imperfect ego = deluded, fallen, sinful, selfish, wounded ego of the imperfect person in need of bio-psycho-socio-spiritual healing, conversion and purification; Perfect ego = ego of the image of God in the prophet or avatara or bodhisattva, the bio-psycho-socio-spiritual model and selfless mold for the reformation of the imperfect ego; Divine Heart = Divine Ego or One Self beyond and within the creative play of the One and the Many.

Second, in postmodern times it has become commonplace to divide human history into three eras: premodern times, the era which is present before the rise of modern science; modern times, the era which coincides with the progress of modern science; and postmodern times, the era which subjects modern science itself to decisive criticism using both intra and extra scientific sources (Sorokin, 1958, 1992; Bortoft, 1996, 2012; Seamon & Zajonc, 1998; Ferrer, 2002, 2008; Nicolescu, 2002, 2008; Christian, 2005; Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; W Smith, 2005, 2012, 2013; Morin, 2008; Kagan, 2009; H Smith, 2009, 2012a, 2012b; Caldecott, 2009, 2012, 2013; Bhaskar & Hartwig, 2010; Benedikter & Molz, 2010; Kelly, 2010; Chopra & Mlodinow, 2011; Bryant, Srnicek & Harman, 2011; Nagel, 2012; Sheldrake, 2012; Slaughter, 2012; Molz & Edwards, 2013; Scharmer & Kaufer, 2013; Masters, 2013). Unsurprisingly, many people habitually assume that the premodern, modern and postmodern sequence in itself is a sure sign of progress. We do not agree with this assumption. We observe that many people in postmodern times are not as competent in being fully alive human beings with all of their ten powers operating consistently with higher levels of virtue and centered in a significantly awakened and illuminating Divine Heart as Śhankarâ (c.788-820), Muhyî al-Dîn ibn al-‛Arabî (1165-1240), Jalâl al-Dîn Rûmî (1207-73), Meister Eckhart (c.1260-1327), Dante (1265-1321), and many other Divine Exemplars, Saints and Sages were in premodern times (Needleman, 1974).

Third, it is important to realize that no one can see beyond their current level of understanding in a particular sense or faculty and in their particular aggregate of ten relatively functioning powers. We refer to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, an example of the Great Chain of Being and Knowing, to explain what we mean. Plato points out that there are some people captivated by the passing shadows on the cave wall, some people who break their chains to discover the reasons for the passing shadows, and some people who break out of the cave altogether to discover the true source of light (Cousineau, 2003). Let’s call these three broad groups of people: prisoners, who work to maintain their normal existence and cannot accept the surreal claims of freedom fighters and light bearers; freedom fighters, who want to help prisoners to break free of their chains but in turn cannot accept the incredible claims of light bearers; and light bearers, who do what they can to relieve the suffering of prisoners addicted to their shadows and freedom fighters addicted to their causes.

In the light of this reading of Plato’s myth, we make the following claims. Within each of the various cultural worlds of premodern wisdom, modern science, postmodern cultural pluralism and integrative theory—such as Wilber’s Integral Theory, Roy Bhaskar’s Critical Realism, or Edgar Morin’s Complex Thought—there are people who operate more or less as satisfied prisoners, who take for granted the current passing parade of their bio-psycho-socio-cultural world, or as agitated freedom fighters, who aspire to change important factors in the parade of their bio-psycho-socio-cultural world, or as gracious light bearers, who understand and celebrate the comparative play of opposites that are interwoven into bio-psycho-socio-cultural worlds (Sharma & Cook-Greuter, 2010; Steckler & Torbert, 2010). We conclude this section on the eye of mind with the observation that all of us have our particular karmic mix of prisoners, freedom fighters and light bearers within ourselves across our various levels of skill in each sense or faculty, and that our particular karmic mix of relatively differentiated functionality functions in a particular mix of bio-psycho-socio-cultural worlds inhabited by one’s self and many others. This being the case apparently no one is a fully functioning human being.

The Eye of Heart

We begin with a definition for the Eye of Heart. According to the perennial philosophy, the Eye of Heart, a point without extension and a moment without duration, is the DivineCenter of a human being (W Perry, 2008). From an external perspective, it is the gateway or sundoor into the formless worlds of Divine Spirit, which is a Unity of Sat (Being), Chit (Consciousness), Ananda (Beatitude or Bliss). From an internal perspective, it is the primal subject that shows, discloses, brings to light, manifests and shines forth the Noumena, Divine Names or Divine Archetypes that are interwoven into the diverse phenomena of created existence (W Perry, 1995). Depending on the symbolism that is being used in a text, it is also called the Supernal Sun, the Eye of Eternity, the Eternal Now, the Navel of the Universe, the CelestialCity, the Resolution of Contraries, the Ultimate Felicity and the SupremeCenter.

We acknowledge that humanity’s wisdom traditions are enduring variations on one universal theme, which is, using Christian symbolism, God—a Unity of Trinitarian Love beyond all opposites and a Unity of Trinitarian Love without opposites (Bourgeault, 2013)—became man—a partial unity interwoven out of unities, polarities, complementaries, oppositions and multiplicities—so that man might become God. To expand a little further, God dis-members or sacrifices Sat-Chit-Ananda so that man might become a child of God within necessarily limited worlds of being, consciousness and bliss interwoven out of interpenetrating unities, polarities, complementaries, oppositions and multiplicities; and with his God-given life man has the lifelong opportunity to sacrifice his current limited bio-psycho-socio-cultural identity so that he might re-member and thus participate more fully in God’s Sat-Chit-Ananda (Campbell, 1968; Oldmeadow, 2004, 2010a; W Perry 2008; H Smith, 2012a).

We turn to Sacred Scriptures, in this case the Mundaka Upanishad, for some inspiration:

Two birds, fast bound companions,

Clasp close the self-same tree,

Of these two, the one eats sweet fruit;

The other looks on without eating.

When a seer sees the brilliant

Maker, Lord, Person, the Brahmin-source,

Then, being a knower, shaking off good and evil,

Stainless, he attains supreme identity (sâmya) (Trans. Robert Ernest Hume).

We offer a reading of this text. The symbolism here refers to ‘two birds’, sunbird and soulbird, the former being a symbol for the Eye of Heart and the latter a symbol for the eye of mind. The first is concentrated inwardly on God’s Sat-Chit-Ananda, on the Supreme Identity of Subject and Object; the second is seduced by the fruits of the Tree of Life as they are presented in outward, phenomenal existence (W Perry, 1995). We note that this ancient symbolism captures the perennial human dilemma about how to live life: does one return from being a particular person to being one with Divine Spirit, or does one get involved in one’s immediate worlds of society and nature, or does one engage this apparent thesis and antithesis in a fully alive, dialectical synthesis?

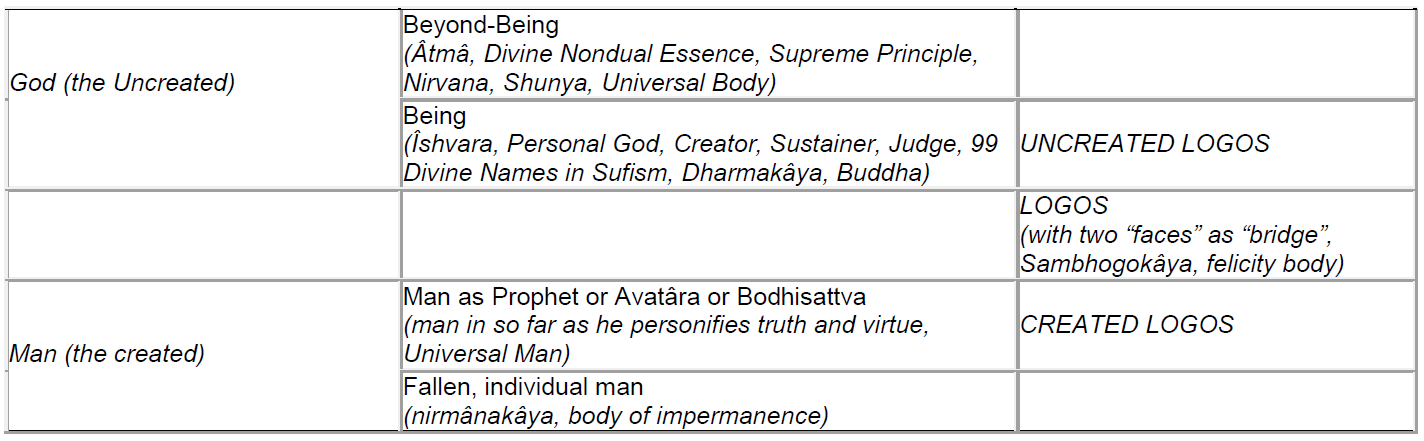

- Table 3. The Role of the Divine Logos in Divine Liberation.

Sources: Adapted from William Stoddart (1993, 2012, 2013) and Harry Oldmeadow (2010a).

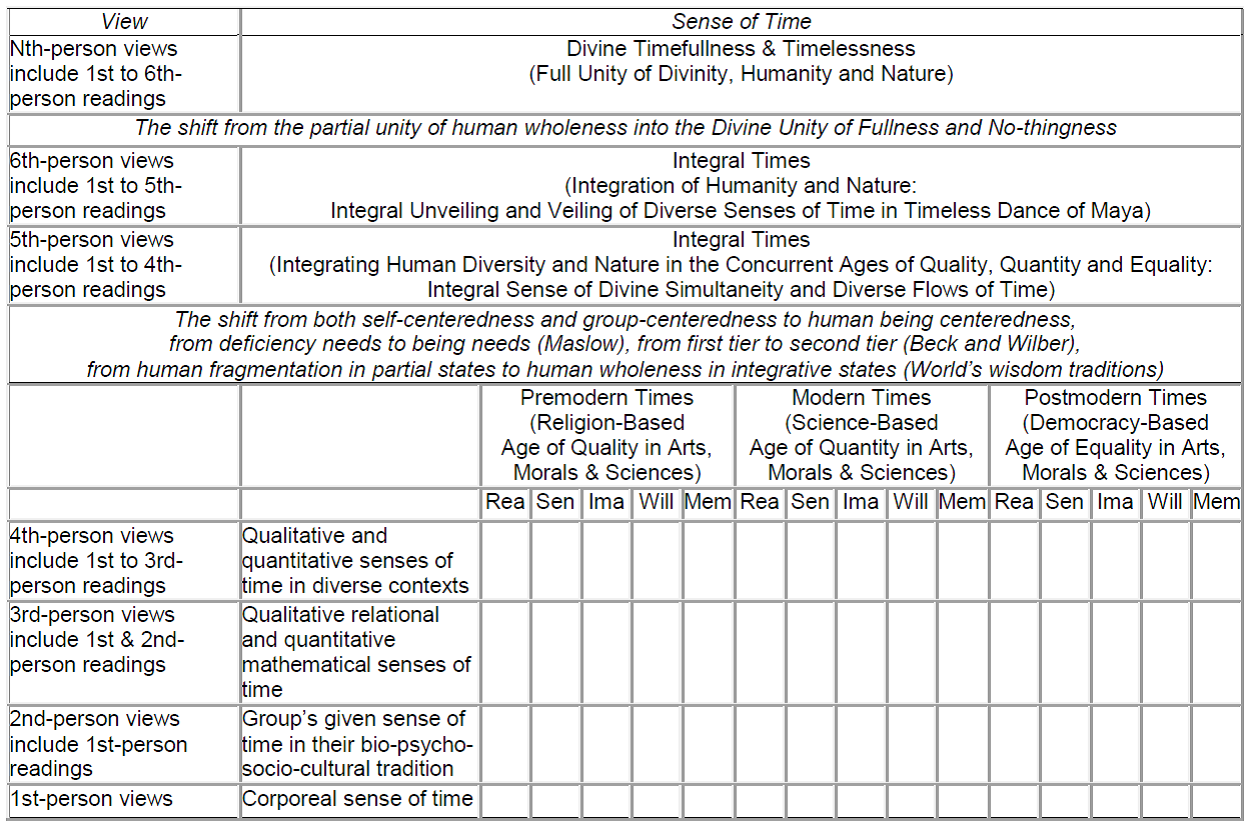

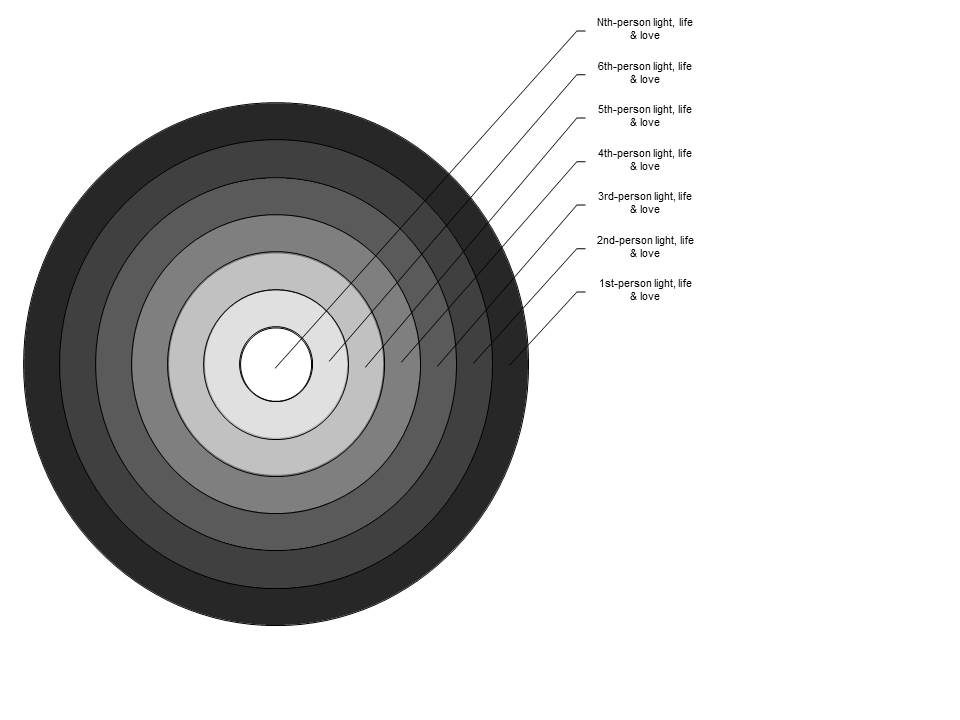

As we have already done in table 1 for the different degrees of skill in each power of the eyes of flesh and mind, we now consider the different degrees of light and love emanating from the Eye of Heart. We notice that the inward world of God’s Presence, beyond the chatting mind, does not make much ‘sense’ for many people in modern and postmodern worlds, for whom only the outward world of interpenetrating phenomena makes any ‘sense’ in their personal experience. Nevertheless, some people faithfully profess and a few innately understand that the one Spirit behind all forms cannot be proven because “a first cause, being itself uncaused, is not prob-able but axiomatic” (Coomaraswamy, 1990, p. 37). For some of these people, who are actually on the path of theosis or Divine Liberation, the first goal to be attained is solving the lesser mysteries of the integral human state in which time is changed into timelessness and one consciously participates in the Divine Simultaneity of All Things. The second goal to be attained is solving the greater mysteries of God (W Perry, 2008). For these people, the role of the Divine Logos in Divine Liberation is to show the Way, the Truth and the Life (John 14:6) from the outward worlds of interpenetrating phenomena through the inward relative worlds of being, consciousness and bliss to a more complete participation in God’s Being, Consciousness and Beatitude, as outlined briefly in table 3 and detailed further in Table 4.

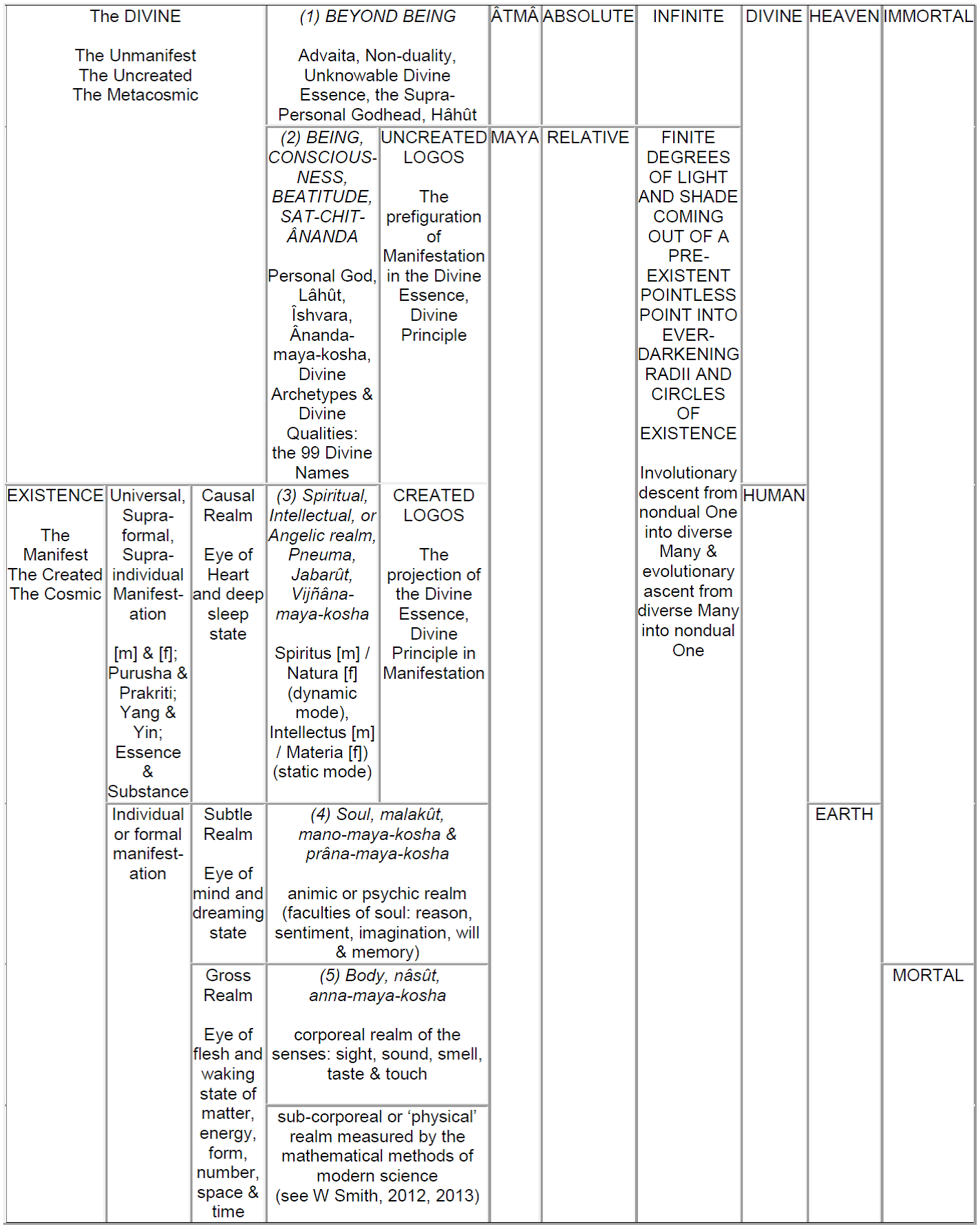

- Table 4. A Brief Account of the Five Divine Presences in the Kosmos (macrocosmos), in Human Communities (mesocosmos), and in a Human Being (microcosmos).

Sources: Adapted from William Stoddart (1993, 2008, 2012, 2013), Ken Wilber (1999c), Frithjof Schuon (2003), Whitall Perry (2008), Harry Oldmeadow (2010a), Wolfgang Smith (2012, 2013) and Samuel Bendeck Sotillos (2013). Abbreviations: [m] = masculine pole & [f] = feminine pole of Existence.

We conclude this brief section on the Eye of Heart with a few comments in relation to Wilber’s Integral Theory. We observe that Wilber’s Integral Theory tends to highlight the spirit of interpenetrating tetra-bio-psycho-socio-cultural evolution from the Big Bang through levels of increasing complexity in matter, life, mind and spirit towards more integral futures but lowlights the perennial teachings on the Divine Simultaneity of All Things seen by the Eye of Heart (Brown, 2006; W Perry, 2008). The difference is crucial: for many wisdom seekers, a preliminary goal on the path of theosis is to release the knots of both individual ego-centricity and group socio-centricity in order to participate more fully in the Redemption of Universal Man, who, in Christian terms, is the Created Logos or Cosmic Christ; for many subscribers of Integral Theory, the Redemption of Universal Man has limited or no significance, perhaps only as a quaint religious belief and value that may be present at early levels of human development that needs to be outgrown. Now we turn from a brief overview of the modes of the knower (the eyes of body, mind and heart) to a brief overview of the various forms of knowledge found in primarily Western civilization in premodern, modern and postmodern times respectively.

The Human Knowledge Quest in Premodern, Modern and Postmodern Times

Our religion is the traditions of our ancestors—the dreams of our old men, given to them in solemn hours of night by the Great Spirit; and the visions of our sachems (medicine people); and it is written in the hearts of the people.

– Chief Seattle (1786–1866) (H.A. Smith, Seattle Sunday Star, 1887).

Premodern Times

Let us begin our brief discussion on the human knowledge quest in premodern times by putting aside for awhile the knowledge claims of modern and postmodern people who are often charged by the latest bio-psycho-socio-techno-logical products. We need to remember that premodern people are not primarily interested in new exciting products. Concerned with the divine condition of their immortal soul in the eyes of God, as shown above in Chief Seattle’s words, they are focused, as given in the title of Ananda Coomaraswamy’s (1984) pivotal essay, “On Being in One’s Right Mind”.

As Coomaraswamy (1984) explains, the most fundamental distinction in the perennial philosophy is, in Latin, “duo sunt in homine” (Aquinas, 1981, II.2, q. 26, art. 4). This means that,

there are two in us: two natures, the one humanly opinionated and the other divinely scientific; to be distinguished either as individual from universal mind, or as sensibility from mind, and as non-mind from mind or as mind from “madness”; the former terms corresponding to the empirical ego, and the latter to our real Self, the object of the injunction “Know Thyself” (p. 212).

The primary knowledge quest for many people in premodern times is, in Eastern terms, samâdhi (i.e., literally synthesis, composure) or, in Western terms, deification or sanctification (i.e., greater participation in God), which is the consummation of the practice of yoga or theosis respectively. With their attention focused on attaining Divine Liberation, devotees of spiritual practices spend their lives working to shift from “humanly opinionated” into “divinely scientific” ways of living within spiritual lineages that are found in the enduring wisdom traditions, as indicated in table 5. Plato, for example, exhorts the soul to “collect and concentrate itself in its Self” (Phaedo 83A, in Coomaraswamy, 1984, p. 212). With reference to the three eyes of knowing, to unpack Plato’s exhortation, the soul (which includes the eyes of flesh and mind) needs to collect and concentrate its ten powers with each power operating with significant degrees of skill in the Self, which, for us, is the ever wakeful Eye of Heart.

The secondary knowledge quest for premodern people is to develop high degrees of skill in using their five senses and five faculties in order to live life well. From nomadic tribes to farming villages to town centers, older generations of spiritual and temporal lords, knights, merchants and peasants educated younger generations into how to develop significant degrees of skill in using their innate ten powers in their intellectual, moral and aesthetic practices of Servile (Practical) Arts and, for the qualified elite, the Seven Liberal Arts (Joseph, 2002; Caldecott, 2009, 2012; Martineau, 2011). At the School of Chartres in France in the 12th century, for example, school masters, some teaching Doctorates in Divinity, taught their students the Trivium of Grammar, Dialectic and Rhetoric, and the Quadrivium of Music, Arithmetic, Geometry and Astronomy in their transmission of the works of Pythagoras, Plato, Plotinus, Saint Augustine, et al. Then training in Divinity itself could be continued amidst contemplative orders that were devoted to spiritual practices that purified and illuminated the Eye of Heart in the process of theosis. Chartres Cathedral itself and many other cathedrals with their palpable sense of the sacred are evident demonstrations of the quality of the medieval synthesis of Divine Knowledge (Querido, 1987; Lings, 1996; Keeble, 2005; Burckhardt, 2010). Outside of Western Europe, elders of high accomplishment amongst Australian Aborigines (Elkin, 1977), American Indians (Eastman, 1911; Brown, 1989; Yellowtail, 1991) and other indigenous traditions, and sacred buildings like the Potala at Lhasa in Tibet, the Taj Mahal at Agra in India, the Blue Mosque at Iṣfahân in Iran, Hagia Sophia at Istanbul in Turkey, and the monasteries at Mount Athos in Greece are a few more demonstrations of the high quality of Divine Knowledge present in premodern times.

- Table 5. The Human Knowledge Quest in Maya in Premodern, Modern and Postmodern Times.

Abbreviations: Adapting from Susanne Cook-Greuter’s (2005) ego development scale, Pre-ego = fusion with bodyself and given family worldspace, 1p = 1st-person ‘me’ egocentric perspective, 2p = 2nd-person ‘our group’ sociocentric perspective, 3p = 3rd-person ‘all of us, humans’ systemic worldcentric perspective, 4p = 4th-person ‘all of us, interrelated living beings’ meta-systemic worldcentric perspective, 5p = 5th-person ‘all living beings’ planetcentric perspective, 6p = 6th-person ‘all living beings’ kosmoscentric perspective, and np = nth-person ‘Divine Integrity in all-possibility’ perspectives. Adapting from Ken Wilber’s (2006) altitude scale, Inf = Infra-red, M = Magenta, R = Red, A = Amber, Or = Orange, Gr = Green, Te = Teal, Tu = Turquoise, and I+ = Indigo + further degrees of development. HML = high, medium, and low levels of skill at each degree of development.

At this point we need to acknowledge that both primary and secondary knowledge quests during premodern times occur in bio-psycho-socio-cultural worlds saturated with sacred symbols. Walter Andrade provides an illuminating account of the role of sacred symbols:

In order to bring the realm of the spiritual and the divine within the range of perception, humanity is driven to adopt a point of view in which it loses the immediate union with the divine and the immediate vision of the spiritual. Then it tries to embody in a tangible or otherwise perceptible form, to materialize let us say, what is intangible, and imperceptible. It makes symbols, written characters, and cult images of earthly substance, and sees in them and through them the spiritual and divine substance that has no likeness and could not otherwise be seen (Coomaraswamy, 2007, p. 227).

Evidently, many people in premodern times live in sacred universes in which access to the “divine and immediate vision of the spiritual” is made accessible through sacred symbols. In contrast, for many people in modern times the inner sacred significance of religious symbols, images and myths is no longer fully intelligible. We need to ask here: what happened for this to be so?

We respond with the claim that many modern people during their religious and/or secular education are trained into mostly literal ways of reading religious symbols, images and myths that emphasize their outward formal aspects that are perhaps appropriate at second-person levels of human development. But rarely do they have access to multi-layered readings of religious symbols, images and myths, as taught in the Latin Patristic theological tradition by Pope Gregory the Great (c.540-604), Saint Thomas Aquinas (c.1225-74), Dante, and more recently Cardinal Henri de Lubac (1896-1991) and Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88), in which four ways of interpreting sacred symbols are used—namely, the literal (formal) sense which refers to mythic and historical deeds, but veils the three spiritual senses, the allegorical sense which illuminates greater degrees of faith, hope and love in Divinity, the moral (tropological) sense which refers to how to act with deeper degrees of faith, hope and love, and the mystical (anagogical) sense which participates in the process of theosis (deification or sanctification)—which are more appropriate at third-person and higher levels of development. With this double loss of access to the original ‘divine vision of the spiritual’ and the deeper significance of religious symbols, images and myths, for many modern people religion seems to be somewhat opaque and childish with at best second-person, sociocentric, sectarian, one-right-way beliefs and values. They are therefore very susceptible to losing their faith in its efficacy for Divine Liberation. With their loss of a deeply felt sense of the sacred, they increasingly seek alternative consolations in their immediate material and social worlds, which are often disappointingly shallow, lacking significant degrees of subjective, intersubjective and objective depth, dignity, nobility and quality.

The Shift from Premodern to Modern Times

We begin this section by acknowledging that Christian Orthodox monks at Mount Athos, and other sacred centers in the Orthodox world, live in premodern times today in a sacred ambience mostly free of modern and postmodern disturbances (Markides, 2002, 2005, 2008, 2012; Rose, 2011; Damascene, 2012). Granted their autonomy by the Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas in 963, Athonite monks have maintained a divine lifestyle based on the process of theosis for over 1000 years, that continues to be a primary divine exemplar for Orthodox Churches throughout the world from Greece to Russia to USA today, living their lives in accordance with the rhythms of ancient Byzantine time with the day starting at sunset, approximately six hours before midnight during Easter celebrations. Many other places, like Tibet before the Chinese invasion in the 1950s, Ladakh in India and Bali in Indonesia before the Western tourist invasion in the 1970s, and much of the Muslim world from Malaysia to Morocco, continue to live or have lived primarily in premodern times in the human quest for Divine Liberation for much of the 20th century. Now we need to ask here: what happened exclusively in Western Christendom to generate the dramatic shift from premodern to modern times?

In our response to this important question, we offer a brief discussion below and another brief outline in table 6. For the interested reader, we mention two important scholars who have provided much more complete responses. Seyyed Hossein Nasr in his Gifford Lectures in Knowledge and the Sacred (1981) and in his Cadbury Lectures in Religion and the Order of Nature (1996) provides a profound account of the desacralization of knowledge in Europe since the Middle Ages using the principles of the perennial philosophy. Philip Sherrard in The Rape of Man and Nature (1987) and Human Image: World Image: The Death and Resurrection of Sacred Cosmology (1992) offers a profound analysis of the eclipse of man in Christian theology, the dehumanization of man in modern science, and the desanctification of nature in modern times, using the principles of the Greek Patristic theological tradition which are celebrated in the works of Saint Maximos the Confessor (c.580-662), Saint Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022), Saint Gregory Palamas (c.1296-1359), and in the Philokalia (1979-95)—which means, the love of beauty—originally compiled by Saint Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1749-1809) and Saint Makarios of Corinth (1731-1805), and recently translated from Greek and Russian Orthodox sources into English by G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard and Kallistos Ware.

For our discussion, we turn to Whitall Perry’s The Widening Breach (1995) for his stark comparison of the very different understandings of reality that are present in premodern and modern times:

Realism in (premodern times) meant the exact opposite of what the word connotes today. The Schoolmen or Scholastics, who had their start in the establishments of learning founded by Charles the Great (c.742-814), the first Holy Roman Emperor, used the word to mean that all seeming reality in our world is entirely infused by the sole ultimate Reality of the Universals or Ideas as propounded by Plato. These are the informing Essences, Archetypes, Exemplars, and Qualities….The Scholastics taught that the Universals are ante res, in rebus, and post res, meaning that their existence is prior to, within, and subsequent to outward things. The Schoolmen insisted in effect that Realism is ‘an assertion of the rights of the subject’, and this axiom shows the primacy accorded to the subjective pole over the objective during the medieval period.

Realism in (modern times) has come to signify the notion that matter and sense objects have a concrete reality in their own ‘right’, they being considered to embody a true existence independently of Ideas—a position which could certainly be called ‘an assertion of the rights of the object’” (p. 59).

The shift from Scholastic realism based on the subjective pole of existence to modern realism based on the objective pole of existence was the exclusive drama of Western civilization that eventually overflowed into and impacted all other civilizations around the globe from the 16th century onwards. Here we select a few scenes from this drama in relation to the marginalization of the Eye of Heart.

- In the 13th century, Saint Bonaventure (1221-74), a Franciscan and a Doctor of the Church, teaches that men and women have three eyes of knowing (flesh, mind, and contemplative heart). However, in the 16th century, amidst many destructive wars of religion many religious and secular authorities consider only two eyes of knowing (flesh and mind) to be legitimate.

- Thomas Keating in Open Mind, Open Heart (1986) provides a reading of the changes that occurred in the Catholic Church from Pope Gregory the Great in the 6th century, who declared the proper goal of spiritual practice to be divine contemplation understood “as the knowledge of God based on the intimate experience of His presence” (p. 20), to the peculiar insular position of Counter-Reformation Catholic orthodoxy, which in the 16th and 17th centuries only authorized contemplative practices within a few contemplative orders, such as the Benedictines, Carmelites, Carthusians and Cistercians.

- The Jesuits, established by Saint Ignatius of Loyola in 1540, became a very powerful and influential religious order from the 16th century onwards, promoting intensively both faith and reason, yet restricting the spiritual practice of contemplative prayer to certain forms of discursive meditation, which in effect considerably diminished the spiritual transmission of living traditions of divine contemplation based on the Eye of Heart in the Catholic Church.

- Henceforth from the 16th century into the mid-20th century, contemplative mystics, such as Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-82) and Saint John of the Cross (1542-91), who made knowledge claims based on the Eye of Heart were considered to be suspect, often subjected to cruel inquisitions by narrow-minded and dim-spirited ecclesiastical or secular authorities, and then either proclaimed incredibly as Saints, as was the case with the abovementioned Spanish Carmelites, or condemned mercilessly to unforgiving punishments or spectacular deaths for what were now being regarded as unconventional spiritual beliefs, values and behaviors.

- However later on in the 20th century, especially after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) proclaimed a renewal of spiritual practices, access to the Eye of Heart is being regenerated in the Catholic Church. Contemplative monks, such as Bede Griffiths (1906-93), Swami Abhishiktananda (1910-73), Thomas Merton (1915-68), Raimon Panikkar (1918-2010), Thomas Keating (b.1923), John Main (1926-82), David Steindl-Rast (b.1926), Wayne Teasdale (1945-2004), et al, share their contemplative views and practices with non-monastic spiritual practitioners, and also participate in inter-religious dialogues with masters of meditation and contemplation from Buddhist, Hindu, Sufi, and other wisdom traditions (Miles-Yepez, 2006; see appendix for Snowmass Conference Points of Agreement).

In sum, Western Christendom’s medieval synthesis, which had been embodied and enacted by great mystics and Saints, like Meister Eckhart, Blessed Jan van Ruysbroeck (1293-1381), Blessed Henry Suso (c.1295-1366), John Tauler (c.1300-61), Saint Catherine of Siena (1347-80), Walter Hilton (c.1340-96), Saint Catherine of Bologna (1413-63) and Saint Catherine of Genoa (1447-1510), began to deteriorate when Christians turned away from Scholastic realism, inner contemplation, the human quest for Divine Liberation, and the process of theosis to become much more interested in the new modern realism, outer observation, and in exploring with their minds and bodies whatever opportunities were available to them in their immediate and expanding natural and social worlds.

Modern Times

One striking feature of modern times that we have already noted is the consistent practice by modern-minded people to limit Reality’s fullness (see table 4) so that it will fit within their particular set of modern assumptions. We observe that the loss of the Eye of Heart does not concern many modern people because their modern worldview does not give the Eye of Heart any legitimacy. This is a clear example of loss of faith, out of mind, out of sight. What does have prominence in a modern worldview is the eye of mind which is used to explore three significant fields of inquiry, which in order of highest to lowest status in modern times are the rational investigation of sensory experience (modern empiricism), the rational investigation of rational experience (modern philosophy), and the rational investigation of religious texts (modern theology). In the following cursory discussion and in tables 5 and 6, we mention a few significant events in the rise of modern empiricism.

The emergence of nominalism in the tenth and eleventh centuries marks arguably the beginning of modern science and the beginning of the disintegration of Western Christendom. What happens is that nominalists, like Roscellinus of Compiègne (c.1050-c.1122) and William of Ockham (c.1285-1349), declare that the world is made of particular individual things (Taylor, 2007; Caldecott, 2009), and that there are no universal essences. Whitall Perry (1995) elaborates on this most crucial matter,

For Ockham there was nothing even to transcend; God could well be ‘up there’, but this world ‘down here’ had it all. For him concepts extra mentum were just that—concepts, and the fewer of them the better, a way of looking at things that was to become designated by others as Ockham’s razor: Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem: “Entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”. This angle of vision, known as the ‘law of parsimony’, may have appeared as but a small hole in the dike separating the ‘upper’ from the ‘lower’ waters [in traditional symbolism, ‘waters’ often symbolize possibilities; ‘upper’ for heavenly possibilities and ‘lower’ for earthly possibilities], yet it functioned as a fissure opening onto the quantitative and exterior pole of manifestation, a breach that over the centuries would unloose the whole form of scientific mentality on which the modern world is fabricated.

The razor shaves off what for Ockham is the surplus fat: pare away the flesh, and the skeleton that remains = reality. This corresponds to what Alfred North Whitehead calls the bifurcation concept (pp. 63-64).

Modern physicist, Sir James Jeans (1933) explains the matter further,

All true progress in natural science consists in its disengaging itself more and more from subjectivity and in bringing out more and more clearly what exists independently of human conception, without troubling itself with the fact that the result has no longer anything but the most distant resemblance to what the original perception took for real. (Burckhardt, 1987, p. 22).

|

Premodern Times |

Modern Times |

Postmodern Times |

|

| Foci of Knowing | Divine Spirit, the eye of heart, quality and subjectivity dominate. The usage of the eyes of flesh, mind and heart are related to local bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions. | Mortal matter, the eyes of flesh and mind, quantity and objectivity dominate. Divine Spirit, the eye of heart, quality and subjectivity are marginalized from most discourses. | Equality and freedom dominate. The usage of the eyes of flesh, mind and heart are self-authorized and related with both local and global bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions. |

| Sense of Time | Time is qualitative, static, vertical, cyclical, and centered on the essential Now. History records the exponential decline in the quality of virgin nature, nomadic and tribal cultures, and religious civilizations from the Krita to Treta to Dvapara to Kali Yugas. | Time is quantitative, dynamic, horizontal, linear and accidental. History records the exponential rise in the quantity of scientific knowledge and resultant technological products, especially during the 20th century and into the 21st century. | Time is the present now. Neither premodern senses of quality, nor modern senses of quantity, when they marginalize the equality and freedom of the self or the marginalized other, are necessarily foremost in what’s happening now. |

| Locus of Authority | Religion orders life. Universal Man in each human person surrenders the illusions and passions of the World, the Flesh, and the Devil in the quest for Divine Liberation, which involves the salvation of all beings from states of disgrace to states of grace. | Science measures material things. Scientists authorize programs of action to solve mainly material problems. Social scientists however struggle with non-measurable, socio-cultural, philosophical, ethical, aesthetic and spiritual problems. | Neither religion nor science authorizes the ways people live their lives. Individuals make their own choices from an overwhelming display of diverse premodern, modern and postmodern options, and then authorize their own lives. |

| Original Condition of Humanity | Eastern and Western sources of Divine Revelation declare that Universal Man, made in the image of God (i.e., in the image of Pure Being, Pure Consciousness, and Pure Beatitude), transcends individuality and is a microcosmic abridgement of the entire macrocosmic Universe of Divine Spirit, human soul and body. | One current version of scientific naturalism posits that the evolution of life forms, including human beings, is dependent on the emergence of lifeless matter in a Big Bang, then on the emergence of living matter out of lifeless matter, and then proceeds due to natural selection and accidental mutation of genetic material. | According to one postmodern worldview, one of many options, everything from the Big Bang to matter to life to mind to spirit in humans and nonhumans is a part of one vast developmental process in which the evolving universe is becoming more aware of its realities and is working to generate integrative global cultures. |

| Current Condition of

Humanity |

Fallen Man, having eaten the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, loses his innate purity of heart. He finds instead all sorts of conflicts amidst the play of dualities (such as subject-object, spirit-matter, yea-nay, odd-even, right-left, good-evil, heat-cold, light-darkness, life-death, man-woman, sound-silence, pleasure-pain, cause-effect, and so on ad infinitum) and of other multiplicities in diverse fields of discursive knowledge. | Within the three cultures of natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities, scientific naturalism is being disputed by anti-reductionists, who do not subscribe to materialist, often dogmatic, beliefs and values that reduce reality to just matter, and who demand more credible non-reductionist accounts of key factors like life, consciousness, interiority, mind, subjectivity, values, purpose, existential and ultimate meaning. | Postmodern worldviews struggle to gain more credibility due to their self-organized complexity, which prohibits any easy familiarity with their claims, and due to their bold challenges to the conventional beliefs and values of others. Postmodern worldviews tend to claim in legitimizing diversity that every view is relative, and tend to make absolute, imperial demands for no imperialisms, no racism, and no sexism, in self-contradictory ways. |

| Some Key Issues in Pre-modernity

in Western Europe |

From Realism to Nominalism:

For Johannes Scotus Erigena (c.815- c.877) and other Scholastics, realism refers to the Ultimate Reality of Universals or Ideas that infuse the divinely enchanted world. Peter Abelard (1079-1142) and St Thomas Aquinas (c.1225-1274) play important roles in the shift from the synthetic, unitive world of Christian Platonism to the analytical, discursive world of Aristotelianism. Nominalism emerges. William of Ockham (c.1285-1349) and other nominalists oppose Scholastic Realism with the novel claim that there are no universal essences, so the concrete fact becomes the final reality. |

||

| Some Key Issues in the Shift from Pre-modernity to Modernity

in Western Europe |

From Nominalism to Wasteland:

Shifts from the subjective pole of existence, the primary concern of religion, to the objective pole of existence, the primary concern of modern science, take many steps, some of which are mentioned here. In De Monarchia, Dante (1265-1321) highlights the crucial ongoing contests between the spiritual authority and otherworldly needs of the Holy Church and the temporal power and rightful worldly needs of the Holy Emperor (or church and state in today’s terms) that result in many divisions in Western Christendom. Nicholaus Copernicus (1473-1543) replaces Ptolemy’s geocentric system with his heliocentric system, which is less compatible with Biblical symbolism. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) points out a way from an animistic to a mechanical explanation of the physical universe in which he replaces “spirits” and “anima” (soul) with mechanical forces. Isaac Newton (1642-1727) introduces an experimental philosophy that investigates a “clockwork” world from which God (i.e. Being, Consciousness and Bliss) is exiled. The philosophical assumptions of modern empiricism, scientific materialism and logical positivism dominate the citadels of power in the 20th century, which prompts T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) to lament the widespread loss of meaning in the modern wasteland, where a civilizing education in the seven liberal arts is marginalized. |

From the Static, Contemplative, Medieval World to the Dynamic, Rational, Modern Enlightenment: Transitions from the qualitative, interior, medieval world to the quantitative, exterior, modern world involve many changes, some of which are mentioned here. Roger Bacon (c.1214-1292) introduces the concept of experimental science. William of Ockham (c.1285-1349) asserts on provisional philosophical grounds that Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem (“Entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”), which in effect over time turns into the controversial bifurcation principle that separates measurable, scientific, ‘real’ things from non-measurable, unscientific, ‘unreal’ things. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) in his new philosophy reduces knowledge from universals to particulars, and works to make wholes out of the sum of the parts. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) uses a new technology, a telescope, to see and do things beyond the normal range of the senses. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) applies mechanical explanations to material and mental things. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) turns the relations between mind and matter into an impassable dualism. David Hume (1711-1776) declares his skepticism about the empirical existence of both mental and material substances. Charles Darwin (1809-1882) explains his theory of evolution by natural selection. | |

| Some Key Issues in the Shift from Modernity to Post-modernity | From Fundamentalism to the Essential & Transcendent Unity of All Things:

The undermining and overwhelming of virgin nature, the guild cultures of arts and crafts, and the longstanding religious virtues of faith, hope and love by modern people who use powerful materialist mindsets to develop superior technological goods prompt a diverse variety of strong reassertions of religious values in the 21st century. Fundamentalists uphold what they maintain to be the only true values regardless of others. Conservatives work to transmit the vital values of their religious tradition onto current and future generations. Liberals seek to make their religious values more relevant in the modern world. Progressives strive to interconnect the religious and scientific values of diverse traditions into a global interfaith network. Contemplatives, such as the Orthodox monks at Mt. Athos, use traditional doctrines and spiritual methods associated with the way of theosis to open the eye of heart to access a divine view of all things. Perennialists, such as Wolfgang Smith (b.1930) and Seyyed Hossein Nasr (b.1933), reaffirm the metaphysical principles and concomitant methods of spiritual realization that reveal the essential metaphysical and cosmological unity of all things, God in all and all in God, using the principle of adequatio between the levels of subject and levels of object, inner and outer, and the laws of analogy to link together different levels of cosmic reality in an integral embrace of the world’s religions, modern sciences and postmodern relativisms. Some thoughtful Christians, such as Stratford Caldecott, propose an anti- nominalist science of the real that re-unites faith & reason, God & nature. |

From Disciplinary Science to Transdisciplinary Science:

The emergence of quantum physics produces revolutionary changes in modern science’s readings of the physical world. To mention only two significant factors, quantum indeterminism replaces classical determinism and quantum nonseparability replaces local causality. In the wake of these radical changes in modern physics, many new sciences emerge and then problems arise about the interconnections amongst, and the integration of, these disciplinary sciences. Here are a few proposals. Edgar Morin (b.1921) explores a creative world in which the constitutive interrelatedness of living organisms includes self-eco-re-organizing systems that have processes of order, disorder, interaction and self-organization. David Christian (b.1946) launches Big History, which tells a grand story of the evolutionary emergence of the physical universe, earth, and humanity over 13.7 billion years. Basarab Nicolescu (b.1942) differentiates disciplinary from transdisciplinary knowledge. The former attends to the external world, uses analytic intelligence and binary logic, has no regard for values, and is oriented towards power and possession; the latter works to understand the correspondence between the levels of reality in the external world and the levels of perception in the internal world; uses a new type of intelligence that harmonizes mind, feelings and body; includes values; and is oriented towards wonder and sharing. Mark Edwards and Sean Esbjörn-Hargens (b.1973) envisage the emergence of integral metastudies & metaintegral studies respectively. |

From the Universal Modern World to Multiple Worlds within Worlds:

New discoveries within different cultural worlds within and beyond Western Europe confound many modern one-size-fits-all assumptions. Here are a few of them. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) authors his three critiques of pure reason (truth), practical reason (morality) and judgment (aesthetics). He however claims with his motto nihil ulterius that there is “nothing beyond” reason. Georg Hegel (1770-1831) lays a dialectical foundation (i.e., the play of thesis, antithesis & synthesis) for an evolutionary understanding of the modern universe. Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) promotes a process philosophy that replaces the classical ideas of space, time and matter with the concepts of organism and event. Jean Gebser (1905-1971) develops an intuition that human history has unfolded and is unfolding through a series of discontinuous mutations of consciousness from archaic to magic to mythic to rational and then onwards to integral. Jurgen Habermas (b.1929) produces a critical theory of communicative action and rationality, a philosophical discourse on modernity, and postmetaphysical thinking. Roy Bhaskar (b.1944) moves beyond both modern empiricism & Kant’s transcendental idealism to create the different phases of critical realism and meta-Reality. Ken Wilber (b.1949) develops his universal integralism through five phases into the current AQAL “all-quadrants, all-levels” model featuring quadrants, levels and lines of development, states, types & zones. Jorge Ferrer (b.1968) champions a participatory spirituality that claims to revision the perennial philosophy & Wilber’s AQAL metatheory. |

- Table 6. A Coparative Account of Some Important Factors in Premodern, Modern, and Postmoden Times.

To which Titus Burckhardt (1987) responds,

According to this declaration…it is the complete ‘human conception’ of things—in other words, both direct sensory perception and its spontaneous assimilation by the imagination—which is called into question; only mathematical thought is allowed to be objective or true. Mathematical thought in fact allows a maximum of generalization while remaining bound to number, so that it can be verified on the quantitative plane; but it in no wise includes the whole of reality as it is communicated to us by our senses. It makes a selection from out of this total reality, and the scientific prejudice of which we have been speaking regards as unreal everything this selection leaves out. Thus it is that those sensible qualities called ‘secondary’, such as colors, odors, savors, and the sensations hot and cold, are considered to be subjective impressions implying no objective quality, and possessing no other reality than that belonging to their indirect physical causes, as for example, in the case of colors, the various frequencies of light waves….a reduction of the qualitative aspects of nature to quantitative modalities. Modern science thus asks us to sacrifice a goodly part of what constitutes for us the reality of the world, and offers us in exchange mathematical formulae whose only advantage is to help us to manipulate matter on its own plane, which is that of quantity (pp. 22-23).

We add a few more comments in relation to this momentous change from premodern to modern times in which qualitative essences, such as the Supreme Unity and the Supreme Identity of Divinity, humanity and nature altogether, are put out of mind and mathematical objectivity becomes the new criterion for ‘reality’. Some readers may have noticed one significant implication of modern ‘reality’ is that many of the ten human powers in each person are not given their full legitimacy with sentiment and imagination in particular consistently devalued as many modern women know from bitter experience. In modern empirical work, reason has clear primacy with the other faculties usually playing secondary roles; and seeing has clear primacy with the other senses usually playing subordinate roles. Thus, using Cartesian terms, the subjective pole of existence in human beings tends to be reduced to res cogitans, the thinking entity, or even worse the power of instrumental reason, and the objective pole of existence in the natural world tends to be reduced to res extensae, extensive entities in length, breadth and depth that can be quantified into mathematical relations (W Smith, 2012, pp. 182-186). Such is modern empirical ‘reality’ after the use of Occam’s razor (i.e. Ockham’s razor). In table 4, modern empirical ‘reality’ is located in the context of the perennial philosophy’s five Divine Presences; it is placed in the little box at the bottom of the table.

The Shift from Modern Times to Postmodern Times

The human spirit has found it very difficult to be content in recent decades with the ongoing desacralization of religion, due in part to second-person literalisms, the ongoing dehumanization of the human condition, due in part to third-person biological (often genetic) determinisms, the ongoing desanctification of virgin nature, due in part to the economic opportunism of careless consumers, and the ongoing loss of faith in the hegemony of modern science, due in part to third-person scientisms. Life is such a bore in this world emptied of divine graces, like truth, goodness and beauty, that many people crave their occasional thrills for some temporary relief, but each new life-consuming game or brand new technological product is bittersweet, sometimes an exciting pleasure, other times a depressing pain, rarely an abiding joy. The concurrent destruction of many human and natural habitats scares many people into imagining all sorts of dystopic futures (Slaughter, 2012), and they feel so frustrated with all sorts of repeated failures to decisively remedy the ongoing diminution of their human and natural worlds. This is evident for the former in the social problem of stranger danger with many concerned parents restraining their curious children from leaving their home when their kids naturally want to explore unexplored worlds in nature and society, and for the latter in the global post-national problem of climate change given the recent announcement that the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to rise from pre-industrial levels of 275ppm to over 400ppm in 2013. From desolate tribes with their premodern loyalties to creative entrepreneurs with their modern enterprises to crusading environmentalists with their postmodern ethics, discontented people can be found everywhere and they are using their political freedoms in egalitarian democracies to escalate their campaigns for all sorts of divergent changes in their bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions.

One person who found he was imprisoned by modern values is Ken Wilber himself. Like many others, he discovered that modern science did not answer his deepest questions. Wilber (2004) writes,

While in late high schools and early college,…my true passion, my inner daemon, was for science. I fashioned a self that was built on logic, structured by physics, and moved by chemistry…. My mental youth was an idyll of precision and accuracy, a fortress of the clear and evident.

And so, as I stood reading the first chapter of the Tao-te Ching, it was as if I were being exposed, for the first time, to an entirely new and drastically different world—a world beyond the sensical, a world outside of science, and therefore a world quite beyond myself. The result was that those ancient words of Lao Tzu took me quite by surprise; worse, the surprise refused to wear off, and my entire world outlook began a subtle but drastic shift. Within a period of a few months…the meaning of my life, as I had known it, simply began to disappear. …I suddenly awoke to the silent but certain realization that my old life, my old self, my old beliefs could no longer be energized (pp. 33-34).

Evidently, Wilber’s first taste of perennial wisdom in reading Lao Tzu’s Tao-te Ching significantly changes his life. However, he soon shifts from his initial readings of the perennial philosophy to creating his own brand of postmodern karma which he eventually calls Integral Theory and Practice. Not fully satisfied with the presentations of perennial philosophy given by Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1968, 1981), E.F. Schumacher (1978), Ananda Coomaraswamy (1975, 2004), Frithjof Schuon (2005), Rene Guenon (2009), Huston Smith (2012a), et al, which assert the primacy of perennial wisdom over modern science, and not fully satisfied with his initiations into Tibetan and Zen Buddhist, Christian and other spiritual practices, which were available in spiritual lineages that often had over-enthusiastic advocates who claimed to have the exclusive one-right-way to Divine Liberation, Wilber diverges from the enduring wisdom traditions centered on immortal spirit (W Perry, 2008) to create his visionary phase 3 integration of his evolutionary neo-perennial philosophy (Wilber, 1983, 1992, 1999c; Visser, 2003) with modern science, especially developmental psychology, and then later on with the employment of additional insights to create his phase 5 integral post-metaphysics centered on the AQAL “all-quadrants, all-levels” habits of his creative mind (Wilber, 2006).

- Table 7. A Reading of the Who x How x What Framework in Wilber’s Integral Theory

Source: Adapted from Ken Wilber (2006).

At this point I need to make a few comments about Wilber’s work, as shown in table 7. In my eyes, it is exceptionally impressive in its visionary attempt to integrate diverse epistemologies (the who of the knower from first to nth-person levels of knowing), diverse methodologies (the how of knowing across the eight methodological zones) and diverse ontologies (the what of the known from first to nth-person worldspaces) across many different levels of human development. So much so, I acknowledge here my profound debt to and heartfelt gratitude for Wilber’s creative work, which I have studied since 1980 and used to a significant degree in this discussion. Yet, when we read his work, we encounter in his divergences from perennial wisdom some awkward lines that reveal some questionable claims. Here we select one significant disproportionate claim, “…when the eye of contemplation is abandoned, religion is left only with the eye of mind—where it is sliced to shreds by modern philosophy—and the eye of flesh—where it is crucified by modern science” (Wilber, 2004, p. 155).

We offer a prompt response. Because he believes that the historical sequence from premodern to modern to postmodern occasions is an evidential evolutionary reality (Wilber, 1999c, 2006), Wilber does not supply in his work a satisfactory critique of modern science and philosophy, centered in quantitative variables, by premodern science and philosophy, centered in qualitative essences, or a satisfactory critique of Integral Theory, centered in vision-logic, by the perennial philosophy, centered in the Eye of Heart. However, when we study the works of Titus Burckhardt (1986, 1987, 2003), Charles Taylor (1989, 2007), Jean Borella (1998, 2001, 2004), Wolfgang Smith (2005, 2012, 2013), Huston Smith (2009, 2012a, 2012b) and Stratford Caldecott (2009, 2012, 2013), six of many accomplished scholars competent in both premodern and modern variants of science and philosophy, we discover what we have attempted to show above that modern science limits itself to objective quantitative factors and that modern philosophy, especially when it associates itself with the interests of modern science, often disqualifies itself from dealing with qualitative essences (Hawking & Mlodinow, 2010; Sheldrake, 2012), whereas premodern sciences and philosophies within the world’s enduring wisdom traditions continue to operate with the qualitative principles of matter, energy, consciousness, light, life, love, truth, goodness and beauty (Nasr, 1981, 1996, 2007, 2010). With these considerations in mind, we ask: how can modern science ‘crucify’ and modern philosophy ‘slice to shreds’ a premodern universal religion that reveals the creative play of the One into the Many, and the Many into the One, even when it has become clouded in the minds of many people from being an immediate contemplative esoteric awareness radiant with light and love as revealed by the Eye of Heart to being an exoteric religious teaching that has become formalized and habituated into an orthodox set of first to third-person beliefs and values by the eye of mind? We defer our answer; however, it is now becoming evident in our discussion that there are some significant problems with the current version of Wilber’s Integral Theory, which we will continue to explore later on.

We now turn to a more general discussion of postmodern times. We provide a short list of some characteristics that many postmodern people have embodied and enacted in their lives, some of which are also mentioned in tables 6 and 8. Many postmodern people tend to have:

- a belief in evolution, perhaps not a neo-Darwinian variant favored by many modern people, and perhaps not a Spirit-in-action variant favored by Michael Murphy (1993), Roger Walsh (1999, 2009), Wilber (2006), Rob McNamara (2013), and other integral evolutionists, yet they are convinced that they are more evolved in significant ways than most modern people with their limited sciences and most premodern people with their limited religions.

- a major problem with premodern religion, which is seen to be a source of absolutism, exclusivism, sexism, racism, feudalism, classism, ethnocentrism, sociocentrism and other sorts of questionable privilege, dogmatic narrow-mindedness and hopeless dim-spiritedness that diminish or deny the dignity, individual freedoms, and equality of human beings.

- a number of problems with modern science, which is considered to be only one of many possible sources of knowledge with no particular source of knowledge essentially privileged, not the official or only source of knowledge as claimed by many modern people, and when it changes its character, in a common Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde move, from the humility of legitimate scientific inquiry into the imperialism of a one-size-fits-all, third-person scientism.

- an interest in putting as many premodern, modern, and postmodern options as possible on the table, or since the 1990s on the internet, and then making their own particular choices from a seemingly endless smorgasbord of knowledge options, and then sometimes creating out of their particular selections an interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary or integrative theory.

We close this section on the shift from modern to postmodern times with a few lines of sublime poetry. The first set of lines is taken from Frithjof Schuon’s (2006) Songs without Names, and the second set T.S. Eliot’s (1974) Four Quartets:

Science demands pure objectivity —

It demands the elimination of everything that is “I.”

But this is only one aspect of knowledge —

The other aspect is likewise a world for itself;

Seen thus, we are a web of I and thou.

True science is not only quantity —

It also requires the living “I.”

(LVII, Ninth Collection, p. 124)

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time

(Quartet 4, Little Gidding)

Levels of Human Development in Premodern, Modern and Postmodern Times

The progress of civilization is not wholly a uniform drift toward better things. – Alfred North Whitehead (1926, p. 1).

What we want to make clear in this section is that all human beings start their growth at conception in the soul and body of their parents and continue their growth in their different senses and faculties through many levels of increasing bio-psycho-socio-cultural complexity as far as their bio-psycho-socio-cultural circumstances will allow them in premodern, modern and postmodern times respectively. Put another way, given growth appropriate bio-psycho-socio-cultural supports and challenges during the different phases of their growth in childhood and adulthood, human beings in all likelihood will grow from less to more developed levels in their various capabilities for thinking, feeling and doing in whatever historical era they may live in.

However, we need to keep in mind at least three things: first, many people suffer with significant degrees of non-existent or careless bio-psycho-socio-cultural supports and challenges during the different phases of their growth in childhood and adulthood that limit to various degrees their bio-psycho-socio-cultural growth; second, many people find enough vital inspiration in their lives to make heroic growth generating choices in all sorts of careless bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions; and third, the general bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions for human growth are evidently different in each historical age, as indicated below:

- In premodern times, the language of symbolism with its multiple levels of significance—communicated through Sacred Scripture, music, architecture, liturgy, and many other art forms, and with the realities indicated by these symbols actualized in various yogas, such as hatha, laya and tantra (psycho-physical training from preliminary to advanced levels), raja (concentration, meditation and contemplation), mantra or japa (divine invocation), karma (works), bhakti (devotion), and jnana (knowledge)—allows for multi-perspectival and multi-layered readings of oral and written religious texts and for participation in intensive on-being-in-one’s-right-mind, spirit-awakening practices that have nourished the bio-psycho-socio-cultural growth of millions of people for millennia.

- In modern times, the language of mathematics with its multiple domains of complexity, taught at primary, secondary and tertiary levels of education, allows for multi-perspectival quantitative readings of nature and the human condition that are being used by many creative innovators to develop all sorts of technological products for increasingly affluent people in materially privileged societies especially in recent decades at least until the inescapable limits of heartless material growth on a planet with limited resources that have been all too quickly depleted kicks in with all sorts of unforgiving bio-psycho-socio-cultural vengeance (see, for example, Paul & Anne Ehrlich’s Can a Collapse of Global Civilization Be Avoided? (2013)).

- In postmodern times, the language of human rights and equality with its multiple levels of interpretation from second to third to fourth-person readings, i.e. from concrete authoritarian to abstract representative to context-sensitive multicultural forms respectively, as described by John Bunzl (2013), is being championed by all sorts of people who value some form of multi-stakeholder democracy over various forms, either religious or secular, of one-right-way totalitarian order in their quest to develop better lives and living conditions for themselves and for other human beings, regardless of their race, sex, gender, age, class or creed.

Given these differences in each historical age, we also need to keep in mind that the specific readings of bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions are different at each level of human development in each historical age. To explain what we mean, we present a reading of adult development adapted from Terri O’Fallon’s (2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2013) important work. We describe six levels of increasingly nuanced development in awareness:

- A self inhabits first-person views, operations and worldspaces.

- Self and other(s) inhabit second-person views, operations and worldspaces in concrete ways.

- Self and other(s) inhabit third-person views, operations and worldspaces, and observe, interact with and ponder the play of first and second-person views, operations and worldspaces in abstract and formal ways.

- Self and other(s) inhabit fourth-person views, operations and worldspaces, and observe, interact with and ponder the play of first, second and third-person views, operations and worldspaces in multiple interconnected contexts.

- Self and other(s) inhabit fifth-person views, operations and worldspaces, and observe, interact with and ponder the play of first, second, third and fourth-person views, operations and worldspaces in diverse interrelated developmental constructs.

- Self and other(s) inhabit sixth-person views, operations and worldspaces, and observe, interact with and ponder the play of first, second, third, fourth and fifth-person views, operations and worldspaces in the diverse interactions of horizontal and vertical unities, polarities, complementaries, oppositions, ternaries, and other multiplicities.

What we want to say is that all of these capabilities from first to sixth-person views, operations and worldspaces are present to some degree in some highly developed people in premodern, modern, and postmodern times respectively. Although highly developed Saints and Sages may have been relatively rare in premodern times, nevertheless they evidently existed in some sanctuaries. These extraordinary people demonstrated remarkable gifts for seeing and reading divine, human and natural essences and substances beyond the normal capabilities of the general population, who seemed to have operated with mainly concrete second-person sociocentric tribal readings of traditional oral texts. Have a look at the life and work of, for example, Plotinus (c.205-70), Shabab al-Din Suhrawardî (1153-91), Jalâl ad-Dîn Rûmî, Meister Eckhart, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401-64), or Sadr ad-Dîn Muhammad Shîrâzî (Mullâ Sadrâ) (c.1572–1640) for evident demonstrations of abstract third-person, context-sensitive fourth-person, and sometimes construct-aware fifth-person, and perhaps polarity-aware sixth-person views and readings of bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions (Copleston, 1985a; Kingsley, 2004; Uždavinys, 2009, 2010; Nasr & Aminrazavi, 2010).

In modern times, artists, mystics, scientists and philosophers with high levels of cognitive, affective and behavioral agility also may have been rare amongst the masses of people with mainly concrete second-person and less often abstract third-person views and readings of bio-psycho-socio-cultural living conditions. Nevertheless, some remarkable creative people, such as William Shakespeare (1564-1616), Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (1646-1716), and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), demonstrated consistently context-sensitive fourth-person, sometimes construct-aware fifth-person, and perhaps polarity-aware sixth-person capabilities, at least temporarily when they were in creative states if not more permanently as well earned character traits (Copleston, 1985b, 1985c).