Maureen Metcalf and James Brenza

Introduction

Maureen Metcalf

James Brenza

This paper will evaluate “Big Data” project implementations through an integral lens and a transformation implementation lens to identify key success factors driving successful projects and also identifying what is missing in failed projects. We selected “Big Data” projects because of their complexity and our belief that successful implementation requires effective leadership, an awareness of and alignment with culture and a strong process based approach to implementation. Big data projects are becoming more common in our technology based world and our ability to implement them effectively will provide organizations a competitive advantage. If they are done poorly, organizations lose valuable resources and in many cases lose credibility among their workforce and possibly within their markets. The stakes are high to get it right and these models provide insight to increase your probability of success.

Have you ever been part of a complex technology initiative that just can’t seem to get completed? Even worse, have you ever seen a complex technology initiative that can’t seem to even get started? If you answered “yes” to either question, chances are very high that you’re not alone.

With the increasing focus on information analytics and “big data,” the risks of lagging or failing projects are rising due to the complexity of the initiatives and the lack of available skilled resources. A recent blog post summarized the broad mix of skills and focus many enterprises expect of their analytic leaders (frequently called Data Scientists):

- Analytic skill set (mathematics, domain knowledge, technology)

- Communication

- Curiosity

- Collaboration

- Commercial acumen

- Customer-centric

- Problem-solving

- Proactive

- Strategic

- Willingness to spend lots of time justifying your existence

(The original blog and discussion is available at blogs.teradata.com/anz/the-top-10-requirements-to-be-a-data-scientist/)

Even though the last one is a bit farcical, it actually highlights part of the problem organizations encounter. A domino effect is that without these skills, initiatives are very likely to fail causing vital resources to focus on self-preservation rather than information-driven transformation. As you review the list, you’ll also discover we expect these resources to be “renaissance leaders” (i.e., resources so broadly skilled that they can fulfill all roles). A direct conclusion is the expectation that a single person carry so many roles may be a leading cause of failing initiatives or constrained progress. Many organizations have realized this and are sharing these roles across many resources. While that mitigates the individual risk, that transference assumes the organization has the processes and capabilities in place to effectively integrate the contributors. With the mix of required skills and team members, transformational initiatives will benefit from a formal structure that decomposes the initiative to phases and to specific projects. These challenging initiatives require holistic leadership that we will refer to in this paper as Innovative) Leadership to drive both the analytic and transformational outcome. An Innovative Leader is a leader who influences by equally engaging personal intentions, personal actions, culture, and systems. For this discussion, we will focus on the combination of Innovative Leadership and Data Scientist.

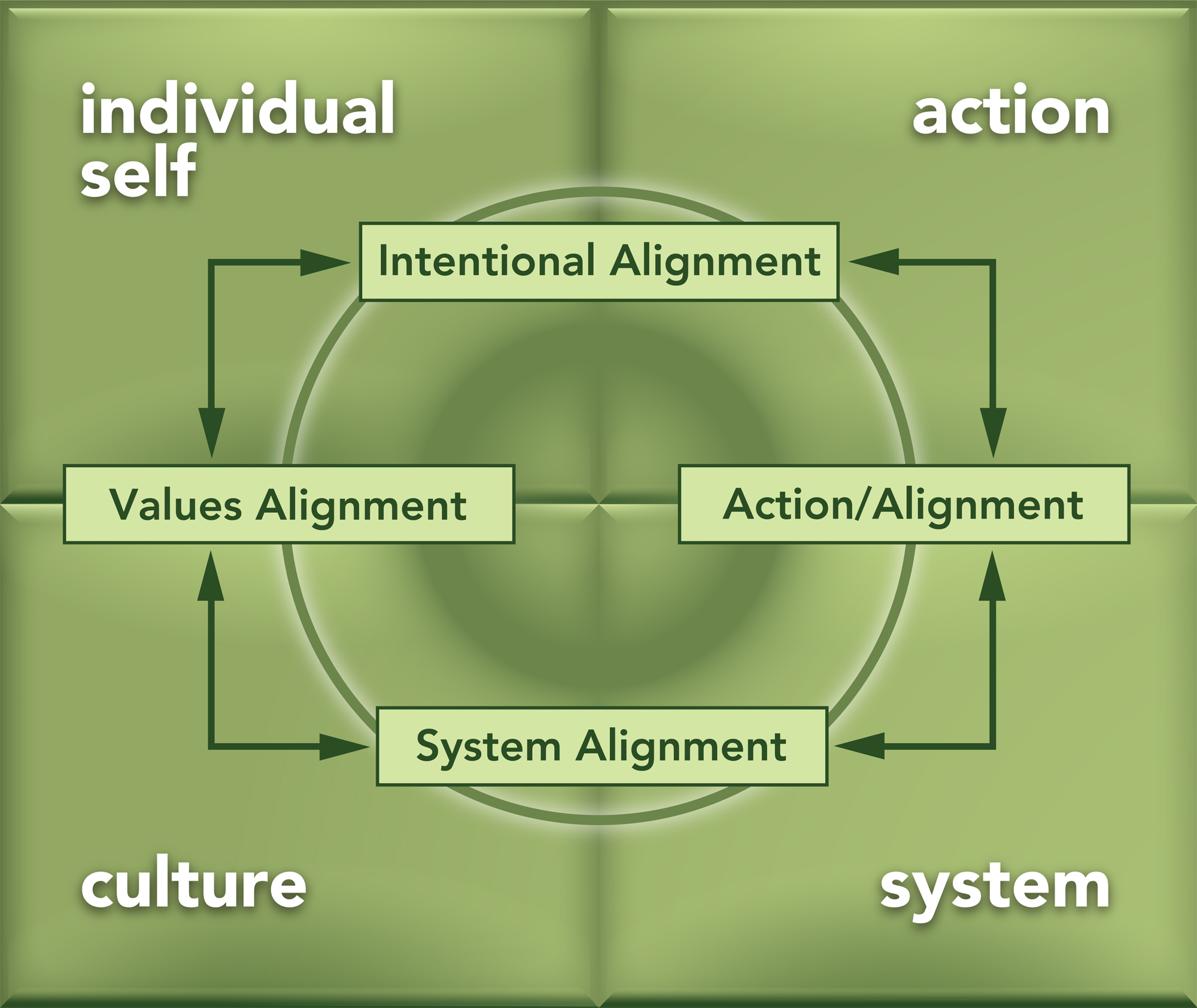

We believe that Innovative Leadership is actually necessary because it uses this entire range of skills to transform organizations. Our article gives two examples of transformations, one successful and one unsuccessful. We’ll use the integral model as the basis for evaluation since it offers an effective assessment framework to improve the leader’s effectiveness and the initiative outcome. The integral model, created by Ken Wilber, looks at the intersection of four key elements, that when aligned, promote successful transformation—and when not aligned contribute to transformation failure.

Alignment Across Quadrants

The key elements of the integral model are shown in the image and include:

- Individual self is the leader’s values, goals, and beliefs. The leader needs traits such as curiosity, proactivity, and a belief that collaboration is important to success. These reflect some of the Innovative Leader traits in the list above.

- Action is where the Innovative Leader acts using the skills referenced above: Analytic skill set (mathematics, domain knowledge, technology), Communication skills, Collaboration, Commercial acumen, Customer-centric, Problem-solving and Strategic skills.

- Culture reflects the organization’s culture and the leader’s understanding of it to create alignment between himself and the culture. This understanding becomes crucial particularly when making changes that are not fully aligned with the existing culture.

- Systems include the organizational and technical systems and processes that dictate how the organization accomplishes its work. The leader needs to understand the current systems, especially those that reward and punish employees and leaders, and ensure these are updated to reflect the new actions required to be successful.

When implementing change, the leader must attend to each of the four areas and ensure they are changing in ways that are well aligned and support one another. To further illustrate this point, the image above reflects key areas of alignment, and all actions in the system have the potential to impact all elements of the system. It is this interconnected nature of leadership and systems that makes this model so important when implementing change. Leaders must take a more comprehensive view of the environment to ensure successful change. It’s no longer sufficient to manage change only from the systems view while ignoring the other three quadrants. To help demonstrate the model’s applicability, let’s review two initiatives.

The first initiative is an example of a great opportunity that never “left the launch pad.” Despite a very strong financial business case to save money and environmental resources, the available resources could not rally enough energy to reach critical mass (or escape velocity). The second initiative is an example of a very complex, very long business transformation to increase revenue and decrease cost. It required more resources for implementation and delivered incredibly positive results. The resources available to both initiatives were very similar, but the outcomes were startlingly different. We will explore both projects through the integral lens, considering how they performed against the four categories in the integral framework. After reviewing the two initiatives, we’ll explore the key differences and provide some insight on how the integral model can improve successful outcomes.

We were reminded while writing this paper how simple the quadrants appear yet how difficult it really is to assign items into a specific quadrant. While we made our best effort to separate topics like qualities and actions, it is hard to fully separate them especially when talking about another person’s thoughts rather than our own. We acknowledge the limitations of this part of the analysis yet still find value in the exercise.

Failed Initiative Example and Analysis

The first initiative we’ll examine had a very strong financial business case and the possibility of saving environmental resources. Both of these outcomes were extremely attractive to the enterprise. The nature of the situation could be classified as a continuous flow problem. It involved an operation that had an expectation to provide service 24 hours per day and 7 days per week. It was using excessive capital resources (which could be bought and sold depending on the long-term needs). It also consumed a significant amount of labor for operations. Other resources necessary were fuel and maintenance on the capital assets.

The solution to the challenge required balancing demand and supply. Demand utilization required statistical modeling in order to more closely match supply with the variations. With improved utilization forecasting, fewer capital assets would be used, less labor necessary to operate them (and the avoidance of unplanned overtime to absorb unidentified usage surges), fuel consumption could be reduced (to scale down cost and environmental impact), and lessen preventive maintenance expenditures. What enterprise wouldn’t relish this opportunity?

The realization of these benefits required the analysis of millions of data elements collected over two years. Each time one of the assets was used, a database entry was available to record when the usage started and stopped. That information was accurate to within one second and included the geo-location code to precisely locate the usage. To help with the usage forecasting, data was available that could be used to predict the day, time and location for usage requests. However, not all usage was controllable. Usage patterns have been associated with inclement weather causing increased utilization. To incorporate this factor, past weather patterns could be analyzed relative to past utilization data to provide a predictive usage pattern based on future weather forecasts and seasonal fluctuations.

After six months of discussions with key leaders, the initiative continued to languish. All of the data was readily available. All of the properly skilled analysts were readily available. Solution examples were readily available. How was it possible this initiative couldn’t “leave the launch pad”?

Using the Integral Model, we can examine four key elements of the situation to identify failure points:

Individual Self – What were the qualities of the leader(s) that contributed to success and failure of the project? The leader who initiated the project was not a hands-on leader; thus, he dictated that the project should happen and assigned it to a team rather than to a specific person and project manager. His lack of specifics meant that no one individual leader was responsible. Each of the leaders in the organization associated with the project indicated that they were committed to the project yet none of them were given this as their primary assignment. While they all wanted the project to be completed, it was not a distinct priority for any of them. Revisiting the list of skills at the beginning of this paper, the leader who chartered the project was not proactive or strategic in the way he led this project.

Action – What leader actions contributed to the success and failure of the project? The variety of departments involved had strong leaders, but no single department had enough skilled resources to solve the entire problem. Additionally, the strong leaders each had other responsibilities that detracted from the full leadership necessary to advance this initiative. Since the enterprise lacked an overarching goal to capture the attention of the distributed leaders, the initiative lacked consistent focus (between meetings) to make progress. Each of the distributed leaders was strong in their respective areas, but their disparate operational foci prevented the assignment of adequate leadership for the initiative. This could also be stated that no singular leader was identified with the responsibility of the solution. The department manager who would benefit directly from the solution was completely dependent on the expertise of the other leaders and lacked the influence to create the necessary call to action. After realizing the difficulty of organizing the necessary resources, the department manager looked for simpler and less impactful solutions that were more controllable. Therefore, the major shortfall started with the senior person who initiated this project not assigning responsibility or following up by being involved and holding people accountable.

Culture – How did the culture contribute to the project success? What actions needed to take place to make necessary cultural changes? The culture of the organization was highly analytic. It was both a blessing and a curse. While most organizations lack highly analytic resources capable of this type of analysis, this organization was blessed with many resources capable of the technical analysis. The cultural focus on analytics was fulfilled by discussing conceptual solutions without taking responsibility for implementing them. This was complicated by the fact that the department which would benefit from the changes lacked the resources to handle the data or the analysis. The culture was not, however, heavily focused on delivering results in a timely and cost effective manner. For this project to be successful, the leaders would have needed to shift the culture to balance analytics and results. The possibility of engaging external resources was raised and promptly dismissed as unnecessary. A clearer focus on delivering results would have reinforced the need for these resources and the value they would have added.

System – Which systems changes were required for project success? The system faults included both technology systems as well as processes to enable the analysis. The solution design was technically complex due to the disparate data necessary to complete the analysis. The data was not already integrated or stored in one location, and also required complex statistical processes to identify past patterns and provide predictive analytics. Interestingly enough, several PhDs with the appropriate skills were readily available and willing to complete the analysis. However, the data elements were stored in different departments and the organization lacked an effective process to integrate the necessary data. Therefore, the results were not delivered—in part, because the processes to implement substantive changes were missing. A core tenant of those processes came from proper project management. By clarifying expectations, roles, responsibilities, formalizing a charter, and empowering the team, a project manager would have been accountable for driving the initiative forward.

Do any of the challenges or symptoms seem familiar? Have you encountered or participated in a similar situation? Despite the frequency of these failures, other initiatives succeed. Let’s examine an initiative that faced similar challenges and managed to succeed.

Successful Initiative Example and Analysis

The second initiative we’ll examine was a business transformation to increase contractual revenue and decrease operating costs. This enterprise was in a highly competitive industry and faced pressure from consumers, retailers, distribution channels, and government regulation. In order to effectively negotiate contract parameters, the enterprise needed to examine hundreds of millions of past transactions to assess past utilization relative to contractual parameters. Additionally, billions of transactions from their competitors were publicly available for assessment relative to their competing products.

This type of analysis was never attempted before. If completed successfully, the enterprise could determine the contract parameters that would move sales away from competing products to their own product. Additionally, they could reduce expenses on contract parameters that didn’t correlate to increased product utilization.

The realization of these benefits would require at least three years. The first year would be required to integrate the data, build the analytic systems, identify the contractual parameters of interest and establish the optimal parameter values. Since most contracts were one to three years in length, the next two years would be required to alter contracts during the renewal process.

Despite the overwhelming challenges and lengthy process, this initiative enjoyed a very strong outcome. This success seems even more daunting since the solution required not just technology, but also organization and business process changes. Using the Integral Model, we can examine four key elements of the situation to identify success points:

Individual Self – What were the qualities of the leader(s) that contributed to success and failure of the project? Each leader on the project understood the project objectives and was committed to its success. Additionally, the individual leaders each demonstrated strong skills in their respective areas and demonstrated high emotional intelligence by initiating conversations that identified weaknesses and leveraged strengths. This required them to take multiple perspectives to develop a well-rounded and balanced perception of the entire environment. From the attributes on our list, these leaders were collaborative, demonstrated a strong commercial acumen, and possessed strong communication skills.

Action – What leader actions contributed to the success and failure of the project? The development of the solution required significant resources and coordination. While a high-level, multi-year plan was established, detailed plans were established for every three to six month phase. To help mitigate the challenges and eliminate progress barriers, the organization established a weekly reporting process to monitor progress against the short-term plans. During very challenging periods, leaders held daily calls with the project participants to ensure that all barriers were effectively removed. All weekly progress reports were shared throughout the organization and made available to executive management.

Leaders held regular retrospective discussions to openly discuss successes and challenges. As issues were raised, all impacted departments collaborated on how to improve the outcome and make the overall effort easier. This level of candor was not easy to establish. The initiative leaders had to establish relationships and foster a culture of openness to ensure that discussions were frank and constructive.

It was vital that the executive leadership established a shared priority and supported the processes necessary to accomplish the outcome. Their open analysis and admission of weaknesses enabled them to seek the necessary assistance. The initiative leaders remained focused on the long-term goal, yet remained flexible for the phase-by-phase changes necessary to fulfill that vision. Additionally, that leadership team established an ongoing dialogue regarding changes (technology, organization and business process) to ensure they were identifying their weaknesses and providing the necessary support.

Culture – How did the culture contribute to the project success? What actions needed to take place to make necessary cultural changes? The culture of the organization was highly analytic. The technology team had strong skills with the underlying technologies, but limited exposure to the business context necessary to structure the solution (or facilitate the organization and business process changes). If the technology team could structure the data for analysis, the statistical analysis team would have their required components to build the models. However, all of those analysts were dedicated to other efforts and concentrated on scientific advancements. Few of them possessed a commercial perspective or interest.

The organization’s culture valued the need for progress above waiting for team members to learn the necessary tools or develop an interest in the analytic methods. By emphasizing their need for results, they quickly approved using external resources with the specialized skills. They also ensured the external resources addressed organization change management as well as technical skills. This balance between analysis, results and solution adoption allowed them to succeed.

System – Which systems change were required for project success? The large volumes of data required for the analysis were never previously integrated. The organization had never attempted to structure or analyze data of that volume. They owned new technology capable of the analysis, but didn’t have a dedicated organization or established processes to complete the analysis.

Rather than let these barriers hamper progress, they acknowledged them and aligned dedicated, focused resources with appropriate expertise. They formalized the team structure, assigned roles and responsibilities, chartered the team and empowered them to drive the vision. The new organization leading the initiative was allowed to engage expert resources to help with the cultural transformation as well as develop their internal resources to ensure long-term success. This allowed them to both accomplish the near-term objectives as well as increase the long term organization capability. By dedicating resources to evaluate the culture and make explicit changes, they were able to create a reinforcing loop between the systems and culture.

They acknowledged these limitations and realized they could not accomplish their vision without the appropriate organization and processes. They changed the organization to match the new requirements and empowered it to utilize expert resources to collaboratively integrate the data and build the analytic models. This was possible since the executive leadership realized these changes were necessary and that they required dedicated focus. They also established a regular reporting process so they could monitor both periodic progress as well as interim results. The organization therefore implemented a range of systems and processes that supported one another and aligned them with organizational structure changes.

Do any of the challenges or solutions seem familiar? Have you encountered or participated in a similar situation? It seems that relatively few complex initiatives attain this level of success. Let’s examine some of the key differences and options you can use to ensure your initiatives are more successful.

Implementation Framework

Many information analytic and “big data” initiatives encounter similar challenges: large volumes of disparate data, new technology infrastructure, lack of highly-skilled resources, new analytic models that may be poorly understood, lack of a structured approach to fulfill the vision, and a culture that may not be prepared for the challenges that will be encountered. This becomes even more daunting when we expect data scientists to provide leadership in quantitative fields, problem solving, business strategy, and communications. As you saw in the initial list, this range of skills is often not seen in one individual; moreover, there are not enough of them who possess the versatility to manage the volume of projects that are currently seen.

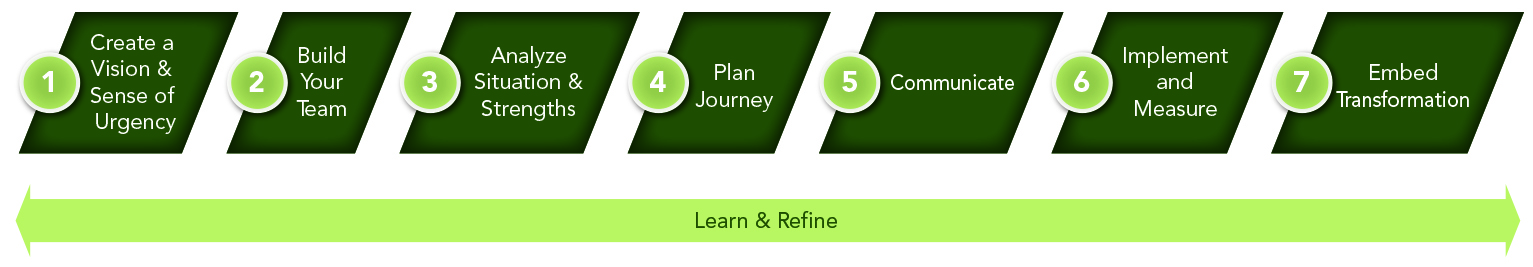

In addition to the key success factors for a big data project, implementing the initiative in a way that respects solid project framework and at the same time creates and maintains alignment between the quadrants of the integral model mitigates significant risk and provides a template for a broad range of organizations to successfully implement complex transformational change. To illustrate, we will offer a model for Innovative Leaders to use when leading “big data” transformation projects.

One of the first elements to enable success is a shared vision to change from the current state. Oddly, this doesn’t require a shared mission or detailed perspective on the future operations. A well-balanced and empowered team can define that end-state. They will need to continually “groom” it as they navigate the change process and allow the data discovery to guide them.

Establishing the team will require formalization of key roles, chartering the team to provide authority to take action, and empowering them to modify the plans. Assigning a leader who is accountable and a regular review process is vital to ensure that the team continues to receive appropriate support and guidance.

Organizational Transformation Process

The structure of the team may vary based on the organization’s need for formal authority and communication openness. The value of open discussions on team progress, needs, and challenges is extremely high. If weak areas (which will change with resource transitions and phase of the initiative) aren’t identified and rapidly mitigated, small issues will fester and potentially derail all progress.

Many skills are expected of data scientists; however, most successful initiatives don’t expect all of these skills to come from single resources. The organizations realize multiple resources are indispensable and establish the culture and processes necessary to facilitate success. This requires very strong, open leaders who have high levels of emotional intelligence to assess and identify the team dynamic, multiple perspectives to identify the gaps, and an openness to admitting weaknesses coupled with a strong desire to mitigate them quickly. If any of these elements are missing, either gaps will remain or they will be identified but not resolved. A necessary ability for the overall team is the ability to identify gaps. Resource and skill gaps can be filled through transfers, hiring temporary help, or building skills. The most important element is the open assessment and identification of the gaps, and prompt action to fill the talent void.

The open assessment of weaknesses and proactive mitigations are vital to ensure success. It may be better to quickly fill gaps with supplemental resources than slowly develop existing resources.

Individual action means that leaders will need to establish a high-level working plan for personal development as well as project implementation to close the gaps identified in the prior step. The old axiom “plan the work, work the plan” applies perfectly. It’s important to have a structured approach and methodology that supports the required analytic discovery process. As the analysis leads to solutions, it’s imperative that organization and business process change methodologies are applied. It may also be necessary to “time box” the discovery process to prevent “analysis paralysis.” An effective technique is to target an 80% complete solution with a plan for ongoing improvements. This will help the team be comfortable with inevitable imperfections and accept small improvements as interim milestones.

After building the plan, the leader needs to be actively engaged in ongoing communication. Communication will cover a range of topics from sharing the vision to setting the pace for implementation and holding people accountable. Shared values provide ongoing and continually reinforced support through initial communications and ongoing progress reviews.

While each of the steps above involves taking action, after the plan is established and clearly communicated, the leader starts to manage the actual implementation and measure progress.

The importance of executive engagement in regularly scheduled retrospectives cannot be overlooked. In many cases, the lack of ongoing engagement can be misinterpreted as a reduced need for the change or waning support for the vision.

During implementation leaders need to support behaviors that favor action over conversation. While conversation and collaboration are critical, action and progress must be equally valued. Since many resources from multiple organizations may be required, new roles may need to be defined that are aligned with the desired change. These will continue to evolve during the entire project. Without evolving goals shared by all members of the team and a structure that supports other team members, individuals only have the incentive to provide optimal performance in pockets rather than toward an integrated and consolidated enterprise outcome.

Additionally, it will be important to establish networks of internal and external resources that are available for all aspects of the change. Initiatives can succeed when organizations structure and implement a range of systems and processes that support one another.

This leads to another key element for the leaders: establishing a framework and incentive structure that balances the individual needs with the organization’s larger objective to act. While some organizations create whole departments focused on the transformation, it may be adequate to charter a team of part-time resources, empower them to define the future state and transition path, and provide ongoing support through scorecards and regularly scheduled reviews.

For the entire enterprise, awareness of the initiative, degree of change, and openness to support the change is vital. This level of focus can’t be held by just the initiative leader, data scientist, or executive sponsor. It must transcend the entire team. Complex information analytic and “big data” initiatives (like any complex organization change) should follow an established discovery methodology and be prepared for the lifecycle that all large initiatives experience. Ongoing awareness that changes will be necessary and needs will vary over the lifecycle is critical for initiative success. Organizations that have situational awareness and the ability to adapt have the highest probability of success.

Conclusion

We looked at big data projects through two different lenses necessary to drive success and reiterate the criticality of considering the four key elements reflected in the integral model of individual self, action, culture, and systems. “Big Data” projects are highly complex and successful implementation requires a leader or leadership team demonstrating the characteristics listed at the beginning of this article, a clear implementation methodology such that listed above, the right team composition for the project and organization, and disciplined implementation. If any of these elements are missing, project implementation is at risk. When all of the elements referenced in this article are addressed in a thoughtful manner by an experienced data scientist and leadership team, the probability of success is high.

References

- Maureen Metcalf, Mark Palmer, Innovative Leadership Fieldbook, Field-Tested Integral Approaches to Developing Leaders, Transforming Organizations and Creating Sustainability, Integral Publishers, 2011

- Maureen Metcalf, Innovative Leaders Guide to Transforming Organizations, Field-Tested Integrative Approaches to Transforming Organizations and Creating Thrivability

About the Authors

James Brenza is the Chief Data Officer for The Ohio State University, brings over 20 years of technology and business expertise to transformational initiatives. James was educated at Akron University and The Ohio State University, and holds degrees in Information Technology, Finance and an MBA. He also holds certifications in Project Management and Six Sigma. He has applied his leadership and technical skills at global and Fortune 50 companies including IBM, GE, BMW and Kroger.

Maureen Metcalf is the CEO of Metcalf & Associates, Inc., brings 26 years of business experience to support her clients’ leadership and organizational transformations. Maureen is a strategic partner who combines intellectual rigor and discipline with an ability to translate theory into practice in each of her client engagements. She designs and teaches MBA classes in Leadership and Organizational Transformation at Capital University. She is co-author of The Innovative Leadership Fieldbook – Winner 2012 International Book Award for Best Business Reference Book. She is also the author of the Award Winning Innovative Leadership Workbook Series.

Pingback: Evaluating Big Data Projects – Paper Published | Metcalf & Associates

Very informative article about Big Data . There is information about every minute detail . I have a similar article related to Big Data that i would like to share with you . You can read it here : http://goo.gl/FKLFg5

This is a great tip especially to those new to the blogosphere.

Short but very precise information… Many thanks for sharing this

one. A must read article!

Thats very good evaluation.It helps while learning about Big data.