Paul Hess

Paul Hess

The modern corporation has many demands placed upon it by various stakeholders: investors, customers, employees, communities, government, representatives of the natural environment, etc. How should corporations respond to these stakeholders? There are three major possibilities: to prioritize one stakeholder, to address all stakeholders separately, or to serve all stakeholders as part of a common good.

Prioritizing one stakeholder is done by the most common model of the firm, the shareholder firm, whose proponents insist that it is necessary to focus on maximizing value for shareholders in order to decide among trade-offs. The critics of the shareholder firm argue that the priority on financial results has become unsustainable because the impacts on other stakeholders are unaddressed and create too many negative consequences and costs in the long run. And there is evidence that it is not the most profitable model of the firm.

Addressing all the stakeholders separately is the response of the most well-known alternative model of the firm, the stakeholder firm. The stakeholder firm includes labor, minorities, women, the natural environment, consumers, etc. While many important issues are raised, the collection of interests under the stakeholder firm has not amounted to a systematic alternative business strategy with new economics to reduce trade-offs so underlying conflicts remain.

Serving all stakeholders simultaneously for mutual gains and a common good is the implicit goal of the sustainable firm. “Sustainable” refers to long term viability economically, socially, and ecologically. The sustainable firm seeks to meet the needs of each stakeholder in a way that is actually good for business by reducing various trade-offs between wages and profits, quality and costs, ecology and profits, and more. The sustainable firm essentially asks: What business strategy lends itself to reducing economic trade-offs to create a common good? The key is a business strategy that is customer focused because that leads to an economics of reducing trade-offs that can create more win-win outcomes among stakeholders—although how it does that is not obvious (Sanford, 2011).

Although customer focused strategy is not new, its full implementation in business organizations has not been fully explored in theory or practice. A key underdeveloped aspect is to look at customer needs more broadly to include more needs of the whole person. Each person can play multiple roles as customer, employee, investor, community member and even the natural “environment.” For example, if the health needs of the customer are designed into a product, the connection to the natural environment is made because the human body is part of the ecology. These are not separate interests. And then trade-offs might be reduced. For example, improving health of customers by lowering toxicity in products also lowers toxic exposure for workers, which can improve health and productivity, lower health care costs, and protect communities and ecosystems. Many costs and quality of life can improve at the same time, if it is done right.

To implement customer focused strategy and the new economics thoroughly requires changes in the entire organizational system, each specialty, organizational culture, and relationship to the ecosystem.

Background: the New Trends

The sustainable firm is still emerging from trends among top economic performers and ways of improving environmentally and socially. All of the techniques are already being used and are consistent with each other, even if no one firm illustrates all features.

The sustainable firm grows out of two trends. The first is a wide set of practices associated with world class business like total quality, six sigma, lean production, and customer focused strategy. These trends represent a new model of the firm that contrasts with the shareholder firm and its academic equivalent, the economist’s model of the firm, yet there has been no complete agreement on what the new firm is or what to call it, even if many studies focused on total quality management, TQM, as its overall framework. (Hess, 2006; Cole and Mogab, 1995; Jensen and Wruck, 1994; Grant et al, 1993).

The second trend is sustainable or “green” business that expands the scope of business strategy to consider use of natural resources in terms of long term availability, cost, and health. Key issues are climate change with destructive weather, and possibility of an epic flood or end of life on the planet; impending resource scarcity concerning oil, water, ocean fish, etc.; and toxicity driving disease epidemics associated with industrialization. There are many models of sustainable business issues and how it affects business in general (Sharmer, 2013; Visser, 2011; Laszlo and Zhexembayeva, 2011; Hawkins et al, 2008; Hoffman, 2000). Some research leans more toward a new model of the firm than others.

Both green business and world class business have much in common: an intention to design whole systems to achieve multiple objectives in ways that reduce economic trade-offs to create win-win strategies for stakeholders.

“The confluence of the quality and environmental movements was a marriage made in heaven. By the late 1980’s, it had become clear that preventing pollution and other negative impacts was usually a much cheaper and more effective approach than trying to clean up the mess after it had already been made….the discipline of quality management could be easily expanded to incorporate social and environmental issues. In the early 1990’s, this confluence produced a flurry of so-called environmental management system (EMS) approaches and “total quality environmental management” protocols, culminating in the advent of ISO 14001, the environmental equivalent of ISO 9000 for quality.” (Hart, 2007:9)

Both quality and environmental innovations reduce trade-offs by setting standards to reduce waste and prevent problems. This paper examines how world class business implies a new model of the firm, and then how green business extends the scope of this firm around natural resources and human health. The focus is on the model, not on empirical results: the model must be determined first before measuring its effects.

The Problem of Change: Needing a Bigger Picture

Lacking comprehensive models of a sustainable firm it is common for firms to only partially implement changes called for in world class methods like total quality management, TQM, and six sigma (Hess, 2006). Some saw the quality revolution as changes in operations and design, and maybe marketing, but without changing human resources, accounting, finance, and management, full implementation did not occur. Implementation has been often blocked by “bureaucracy” and the practice of managing with financial numbers rather than customer and process metrics. Previous forms of organizations often operated as separate parts with conflicting objectives and trade-offs: Finance wants numbers based on past performance, not innovation. Accounting wants cost reduction per unit that contradicts managing whole systems. Human resources wields individual incentives that do not support team work. The organization is not listening to customers because it pushes products at them. Managers with command hierarchies lack processes for facilitating transformation. Green business is implemented as an extra-curricular charity for public relations, rather than changing the way business is done (Laszlo and Zhexembayeva, 2011). These are typical barriers and structures that must be replaced for deep and consistent implementation of new practices. This study addresses these practical problems with a more complete map of the new strategy, economics and organization, in systematic contrast to what it replaces, rather than assuming newer innovations in business can simply be added on to the shareholder model of the firm.

This paper provides a framework for modeling firms derived from a broad review of academic and business literature along with empirical observation. There is one overall theme: how customer focused strategy changes nearly everything and is at the center of four major transformations: organizational, economic, scientific and moral. These four transformations are specified as 9 principles that shape 10 sets of organizational features.

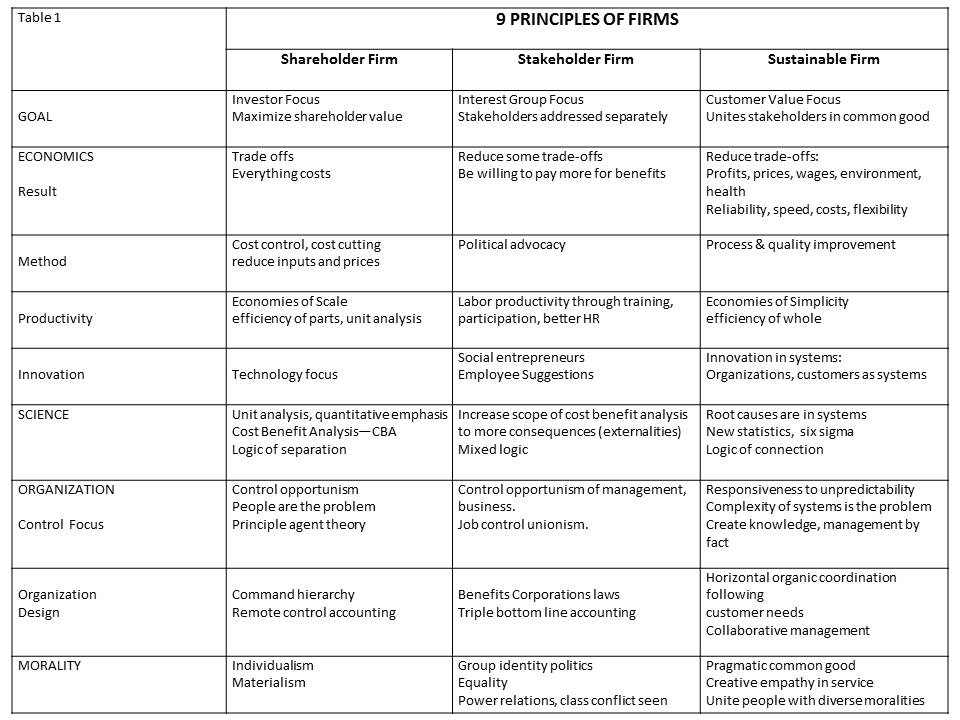

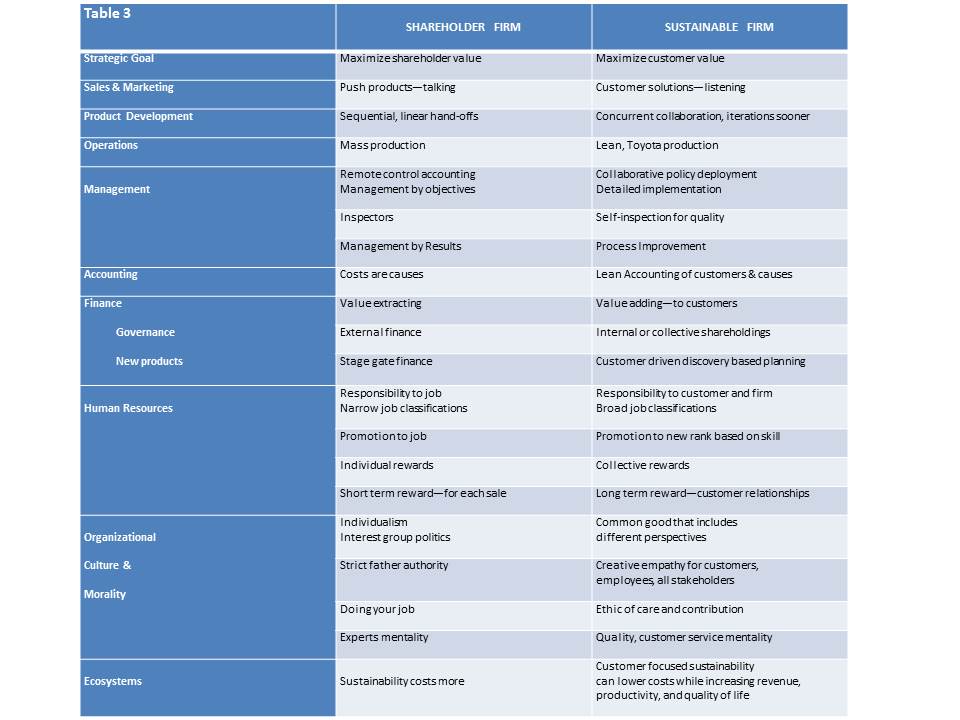

Nine kinds of principles of economics define models of the firms: goal, position on trade-offs, key objective, method of analysis, productivity, innovation, control focus, organization design, and morality. Principles for each firm are summarized in Table 1. The principles shape all ten features of organizations: strategy and innovation, sales and marketing, product design, operations, management, accounting, finance, human resources, organizational culture, and sustainable strategy. Table 3 presents a summary of three models of the firm.

Four Transformations in Management

The sustainable firm involves four transformations in management that begin with a customer focused strategy as a business goal that can unite stakeholders around a common goal.

- Organization: Customers pull the horizontal organization with collaborative management.

- Economics: Customer focused strategy leads to a new economics of simplicity that reduces trade-offs and costs while fostering innovation in systems in potentially all parts of the business.

- Science: Systems theory is the framework for scientific methods applied to improving work processes, interpreting data, root cause analysis, and the new applied statistics.

- Morality: The purpose of the firm is to serve all stakeholders simultaneously as a common good, more or less, that includes people with different moral and cultural perspectives under new work ethics of care, contribution, and creative empathy.

These four transformations are defined as 9 principles and then elaborated in 10 organizational features.

9 Principles of Firms

The nine principles of each firm are a combination of scholarly ideas and common themes found in business practice. Some of these principles are very familiar, others are implicit. These are summarized very briefly to give an overview of each firm.

Shareholder Firm

Goal. The shareholder firm’s goal is to maximize returns for shareholders and return on investment. Yet declaring the priority maximizing returns does not necessarily make it the most successful way to increase returns. For example, investors and financial markets often exert pressure to extract financial value in the short-term, rather than add more value in the long-term.

Economics

Results. The shareholder firm assumes that there are economic trade-offs. In fact, the assumption of the inevitability of trade-offs is used to justify the priority on returns for investors: one priority must be selected to decide among trade-offs between alternative objectives (Jensen, 2000). It tends to see everything in terms of costs and separate, competing interests.

Objective. With the cost focus a major objective is to reduce the cost of inputs through cost control and cost cutting, that is, reducing the quantity of inputs and prices, rather than looking at how inputs are utilized. Cost cutting does not look at causes of costs, such as, inefficiently designed processes, products, and systems.

Productivity. Costs and returns and are analyzed as separate units of work in a highly specialized division of labor. Costs have been calculated per unit of out-put by a single machine, for example, instead of total costs of production. This is the approach of classical economics with its foundational principle of economies of scale. Efficiency is increased by further specializing production into separate units. While specialization is one way to increase efficiency, it also presents problems for coordinating the whole system and measuring total costs. Calculating by units is also done under marginal analysis, which examines the gains from the next increment of action, like selling remaining inventory at a discount, without examining the consequences for the system and consumer behavior, for example, to what extent customers will wait for the discount instead of paying the regular price.

Innovation. The focus on separate units of production shapes the way innovation is seen: the focus tends to be on very concrete and distinct things like hard technology, rather than on examining complex relationships like production systems. There is an emphasis on technology as the source of productivity gains and innovation. This overlooks other kinds of innovations in technical processes and human relations.

Science

The framework for analyzing data focuses more often on separate units of analysis in financial and quantitative terms. Choices between different kinds of trade-off are made through cost-benefit analysis—CBA. There is a lack of causal analysis; rather, choices are made among different effects or costs. CBA is used to decide among existing options, rather than create new options that might reduce trade-offs through innovation.

Organization

Control Focus. The control focus is to control opportunistic and selfish behavior as expressed in principle agent theory: Investors need to control managers through various means from bureaucracy to individual incentives (Jensen, 2000). People are assumed to have individual interests and a relatively high probability of acting in self interest in ways not aligned with the aim of the organization. The same approach is taken toward labor. Labor is also a variable cost that is a major target of cost cutting. People are the problem, not systems or environments.

Organization Design. The financial way of thinking aligns the organization with the financial market, which, in turn, influences daily operations by linking financial accounting to management accounting under a type of command hierarchy known as “remote control.” (Kaplan and Johnson, 1987). Remote control uses financial figures as a major source of information to control costs and people. The weakness of this practice is that financial information cannot convey causes of performance or results for customers. Top down organization follows a “logic of separation” and specialization that structures functions into separate silos that lack coordination cross-functionally and horizontally.

Morality

The morality of the shareholder firm is individualist, motivated primarily by material ends. The assumption of individualism leads to mistrust and use of control mechanisms internally based on bureaucracy or incentives. These features of the shareholder firm become clearer by way of contrast with the stakeholder firm.

Stakeholder Firm

The stakeholder firm expands beyond some limits of the shareholder firm but does not replace all the limiting basic assumptions of the shareholder firm, although it is often a step toward the more fundamental change of the sustainable firm. The stakeholder firm is often a politics within the shareholder firm.

Goal. The goal of the stakeholder firm is to include the interests of other stakeholders who have been excluded under the shareholder firm: labor, women, minorities, the environment, communities, consumers, etc. (Freeman, 1984). This is “corporate social responsibility” (Visser, 2011). Stakeholder firm proponents may state their case rather meekly or defensively as, “We acknowledge that returns for shareholders and profits are important, but other things are important, too.” However, in some areas the stakeholder firm’s strategies do have strong arguments for economic benefits.

Economics

Results. Stakeholder reforms reduce some trade-offs within the shareholder firm. For example, labor advocates make the case that treating labor well is something that improves productivity and reduces cost trade-offs. Thus, labor is an investment in the system rather than a separate cost to be cut. The case for reducing trade-offs has been made around environmental sustainability: efficient energy reduces business costs, for example.

Objective. The main objective of advocating for stakeholder interests is done through politics using moral arguments. This sometimes involves justifying paying more for the social benefits rather than reduce trade-offs. Sometimes there better results for all stakeholders are offered.

Productivity gains are focused on increasing labor productivity through training and participation in decision-making, and more supportive human resources practices. These labor centered practices reduce trade-offs by increasing productivity and the size of the pie to be divided.

Innovation advances through suggestions from workers, participation, collaboration, and redesigning human resources, which contributes toward the sustainable firm. Outside of the firm social entrepreneurialism is a way to addresses unmet economic and social needs, yet this does not change systems of existing organizations.

Science

The stakeholder firm interprets data about important issues by expanding the scope of analysis beyond maximizing individual units. Its cost-benefit analysis considers the larger consequences or externalities, beyond profits and costs to the firm: the effects on the environment, community, employees, consumers, etc. Yet many of these interests are still addressed separately, not as a system so that any one issue is addressed fundamentally and in a way that does not conflict with how other issues are addressed.

Organization

Control Focus. The control focus still often emphasizes control of people, but the direction is reversed to control potential selfishness and opportunism of management within the firm, and corporations in the public and natural environments. Job control unionism reflects this mistrust with its efforts to resist being exploited by management by not working out of job classifications without the pay of the higher classification.

Organization Design. The stakeholder firm’s organizational design aims to create more equitable results among stakeholders. The legal expression of this is the newer Benefits Corporations (B Corp)in 11 states that give legal weight to pursuing social goals beyond returns for investors (Browkaw, 2012). The B Corp protects against law suits from investors who want to follow the shareholder firm model. The other purpose is to require companies to report to their non-financial results to prevent dishonesty, such as, “green-washing” false marketing about environmental claims.

The stakeholder firm may use multiple criteria of social accounting known as the triple bottom line of financial, social and environmental goals. While this does take into account important issues, its downside is that it is a collection of interests without a business strategy in a logical order to show how to achieve goals, just like the “balanced scorecard” from the Harvard Business School twenty years before, (Kaplan and Norton, 1992).

The B Corp and triple bottom line can support the sustainable firm, yet on its own without an alternative business strategy it is still focused on controlling opportunism, rather than aligning the firm so that desired results occur by design as part of business.

Morality

The morality of the stakeholder firm is concerned with equality of various groups or “identity politics,” based on the insight that power and politics shapes economics. This insight provides a critique of the shareholder firm’s idea that “markets” are natural and that existing outcomes are the result of individual wills. While bringing power into the picture contributes toward a more complete account of firms, stakeholder politics overlooks how people act out of varieties of moralities–traditional, libertarian, progressive, etc.—to create varieties of associated firms, business practices and institutions.

The stakeholder firm is not a complete alternative but is between the shareholder and sustainable firms. On the one hand, it is a stakeholder politics within a shareholder firm that relies upon the state and laws to regulate the shareholder firm. On the other hand, the stakeholder firm introduces a few innovations in systems that are taken further under the sustainable firm, like insights into labor productivity, the Benefits Corporation and triple bottom line.

Sustainable Firm

Goal. The purpose of a firm is to create and serve a customer (Drucker, 2000). Yet, there is more: The business goal of serving a customer actually supports serving other stakeholders for the simple reason that customers provide revenue to pay for investors, employees, and taxes for public investments. In fact, “customers” represents human needs in general. A customer focus initiates a chain reaction of benefits for employees and other stakeholders and can actually create larger returns for shareholders than by aiming directly to maximize returns for shareholders. The customer is the “foundational stakeholder” that aligns employees, communities, ecosystems and investors around a common good (Sanford, 2011). New strategy is about creating shared value (Porter et al. 2011). The customer focus makes the connection between humanity and nature by including the human body through issues of health.

Economics

Results. The economic result is to reduce economic trade-offs between customer value, prices, profits, wages, natural resource use, health, etc. (Eccles and Serafeim, 2013). The starting point for reducing trade-offs is not obvious: it begins with metrics for customer value like “quality” in terms of fewer defects that also lower costs. Quality lowers costs because things done right the first time do not waste scrapped materials, do not take time to rework, and do not lose customers. By wasting fewer resources, savings can be shared by the firm, customers, investors, and the ecosystem. Instead of automatically slashing wages, costs are lowered by utilizing inputs better through simplifying processes step by step throughout the whole system. Quality improvement is important strategically because it ignites a positive “chain reaction” that simultaneously lowers costs and increases productivity, profits and jobs—the “new economics” as described W. Edwards Deming (1993; 1986). Thus reducing economic trade-offs creates benefits for multiple stakeholders: employees, investors, customers and communities. Economic cost trade-offs are achieved in the operations of manufacturing and service delivery, product design, and sustainability strategy.

Key Objective. The key objective is process improvement to improve how work is done. Processes are about how inputs are utilized, not just the price of inputs. Process improvement is driven by aspects of customer value that require internal improvement: Product reliability leads to internal quality as defect reduction; customizing features leads to flexibility of machines, workers, and organizations; and delivery time goals spur designing simpler, faster processes that also lower costs. All processes in organizations can be improved. The collaborative management process is the actual process of process improvement itself, backed by a culture of improvement and supportive human resources and rewards.

Productivity and efficiency gains are sought at the level of entire systems for economies of simplicity. All key objectives in organizations like quality, speed, flexibility, and cost are improved by simplicity, and improving these factors improves simplicity for virtuous circles of positive feedback loops. This is the Toyota or lean production system, the most famous example that has inspired organizations of all kinds to improve. Even some hospitals have been are inspired to learn from the Toyota’s system. Economies of simplicity can be achieved with any process. The most notable examples are from operations and design, with support from consistent accounting measurements (W.E. Cole and Mogab, 1995).

Innovation. Innovation in systems means that there can be innovation in entire systems, A system can be defined at any level from specific work processes, to the entire firm, to the ecology of the planet. Innovation can occur in any aspects of organization like concrete processes, machines, hard or soft technology, and in its culture. The customer’s needs can be understood as a system for more comprehensive “customer solutions.” This is the most radical form of innovation: to understand human needs more deeply and broadly, until each person is seen as playing the roles of multiple stakeholders, including as a part of the ecosystem through their physical health and resource use.

Science

The framework for analysis of data is systems theory to analyze root causes in systems. Systems theory looks at how all the parts of an organization are related and how problems in one area of an organization are often caused by another area. For example, defects in manufacturing can be caused by problem with design of the product, which can be compounded by the methods of accounting and finance that constrain design processes. The root causes of problems often originate in complex relationships. By looking at root causes in systems, trade-offs between different objectives can be reduced, for example, the causes of quality problems are also causes of costs.

Systems analysis is supported by the new statistical methods of six sigma that determine root causes of problems by examining the natural variation of systems; whether problems are due to the design of systems or individual error. This insight shifts an organization’s control focus to systems under “management by fact.”

Organization

Control Focus. The control focus is on the complexity of systems and unpredictability of environments, which requires that organizations be responsive rather than controlling. Individuals and labor are no longer blamed as the primary source of problems so there is more trust in the organization rather than a culture of blame and fear of making mistakes that leads to covering-up quality problems that are actually caused by the design of processes, products, and systems. With more trust employees and management collaborate to create knowledge to serve customers. Management processes include firm-wide collaboration to make management a process rather than a position. Employees manage and improve their own work processes with six sigma and other techniques. Staff functions are aligned to serving customers: Human resources match rewards to serving customers, lean accounting creates new knowledge with customer focused metrics, and finance is aimed at adding value to customers. Management and staff support horizontal, cross-functional alignment of line functions to serve customers under “management by fact.” All aspects of organization practice responsive alignment to customers.

Organization Design. The sustainable firm is driven by consumer markets through a horizontal organization that follows customer demand across the functions of sales, marketing, design, and operations. A “chain of command” originates in the customers themselves and leads to a horizontal organization pulled by customer demand in which every work unit is a supplier to a customer and a customer of a supplier communicating directly in the flow of production or service delivery, which can be sequential or simultaneous with cross-functional collaboration. This system is more self-regulating and follows market signals, not just price signals: it uses detailed information about what customers want and process capabilities to deliver value. Horizontal network organization blurs distinctions between firms that collaborate in process improvement with formal boundaries being less relevant (Eccles and Norhia, 1992). Horizontal and collaborative organization is examined in detail as ten sets of features that illustrate nine principles.

Morality

The morality of the sustainable firm is a pragmatic common good of results for stakeholders. Its values are a “creative empathy” for being of service to others. It is interested in uniting diverse moral orientations rather than insisting on one morality for everyone. Yet the morality implied is not relativistic, as explained later. This morality arises implicitly through understanding customers and collaborating across specialties and cultures. Morality shapes the entire organizational culture. This will be explained further below.

Table 1. 9 principles that define firms.

The Sustainable Firm

Ten Features

Ten features of the sustainable firm embody the 9 principles. We first look at strategy and the line functions that serve customers: sales and marketing, design, operations. Next is the management process that drives implementation and improvement, supported by staff functions: accounting, finance, and human resources. Organizational culture discusses the new morality implied. Finally, ecosystems looks at a customer solutions approach to sustainable business.

Strategy: Innovation for Customers

The key issue of strategy has been defined as finding a focused position in a market space (Porter, 1996). The choice of position is about which customers to serve based on firm capabilities relative to what competitors cannot do as well (Ohmae, 1991). This can be called the 3 Cs. Let’s see how models of the firm stand up to these general definitions from the strategy literature.

Shareholder Firm

Maximizing shareholder value is actually a goal and outcome, not a strategy, as one of its earliest proponents insists, Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric remarked:

“On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy… your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products. Managers and investors should not set share price increases as their overarching goal. … Short-term profits should be allied with an increase in the long-term value of a company.” (Gurerro, 2009)

The shareholder firm lends itself to strategies that can be stated in financial terms like return on investment. Common strategies are cost cutting, mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, either buying or selling, monetary transactions, not innovation. But this is not the full scope of strategy. The shareholder firm does not have a particular position on strategy and the 3 Cs. The results of the shareholder firm since 1976 when it became popular are actually a decline in returns to shareholders and return on assets began to decline (Dennison, 2011; Hagel et al 2011; Martin, 2011).

Stakeholder Firm & Fragmentation

The stakeholder firm also does not have a distinct position on strategy. The stakeholder firm as a collection of separate interests can be used as an analogy to all kinds of fragmentation of efforts that disconnect customers, capabilities, competitor assessment, and innovation processes. Firms can be too focused on any one of those relative to others and lack integration of the three C’s.

The stakeholder firm’s most direct implications for strategy stem from its interest in employee empowerment and participation. With the idea of stakeholder participation many suggestions may be incorporated in product design but the result may be too many features and products that are not aligned with customer needs. This is a form of being too capability focused on exercising the capabilities of workers to contribute.

Similarly, a lack of strategic focus can also arise from trying to “be all things to all customers,” in the words of Michael Porter (1996), and also proliferate features and products that do not match demand. The firm may be customer driven in very general sense but runs the risk of not satisfying any set of customers very well because it has not matched the firm’s capabilities and what it can do better than competitors.

Being overly competitor focused on market share can lead to cut-throat competition and price wars that drain companies. This has happened with Japanese firms like auto companies that can be status conscious relative to other firms. Both product design and pricing can be a reaction to what competitors are doing, which may distract from actual customer needs (Johannsen and Nonaka, 1996). Being competitor focused can also broaden product offerings by trying to match what everything everyone else is doing, thus lacking strategic focus.

Similar fragmentation of efforts can be seen technology innovation for its own sake that looks for a customer after the fact, which can be hit or miss. While firms can explore in research and development with some eventual benefit, the links back to customers during the process are often weak (O’Rielly et al, 2009).

The merits of focus were demonstrated by Porter et al (2000) in the case of American electronics firms that achieved competitive advantage over Japanese firms by focusing. Apple, for example, with less than a dozen products contrasts with NEC with hundreds of products, which makes it impossible for NEC executives to know all products to talk to customers comfortably. The process at Apple is different than that of the participatory stakeholder firm, with much responsibility in the hands of one person, former CEO Steve Jobs who personally reviewed projects for relevance to strategy. Killing projects is not always considered “nice,” especially in the stakeholder firm. Apple integrates elements of strategy.

Sustainable Firm

The sustainable firm addresses the key strategic question of positioning: which customers to focus on, relative to firm capabilities relative to what competitors cannot do as well—the 3 Cs (Ohmae, 1991). It focuses with more emphasis on customers and the dynamic aspect of capabilities: innovation. This was stated by Peter Drucker thus: The purpose of the firm is to create and serve a customer, and its two key functions are marketing (to create the customer) and innovation, according to (Drucker, 2000). Innovation is the dynamic processes between the three Cs that makes strategy emerge continuously with feedback from customers about organizational capabilities while learning from competitors and other firms. Here’s how the sustainable firm addresses the three Cs.

Customer Focus and Positioning

Firms focus on customers that match the firm’s capability to provide more value to customers than that of a competitor, or to find a niche without direct competitors. One way to avoid direct competition initially is to expand the market into new areas for a “blue ocean strategy” (Kim and Mauborgne, 2004). In a new market space the firm has no competitors and can charge more. A blue ocean strategy can benefit customers who would otherwise not have the product at all. Blue ocean strategy generally requires innovation in products to capture new needs either of existing customers or new customers.

Blue ocean strategy can include the “bottom of the pyramid” of the world’s poor who are not yet a market. Being customer focused would involve meeting their needs, not colonizing their societies and imposing corporate control and commodities designed for other parts of the world. Drawing upon indigenous resources and community collaboration are important to expanding markets sustainably (Hart, 2007).

In determining which customers to serve, if there are existing customers there can be advantages to starting with them because there are relationships with more communication and information about needs. The objective can be to diversity with each customer and delve deeper into their needs when innovation is an option outside of a simply commodities market. This is customer share: creating more products to acquire a greater share of a customer’s wallet, rather than the more traditional objective of capturing market share of an existing product, which is more competitor focused (Vandermerwe, 2004, 2001, 2000). This follows from providing solutions with multiple components to meet more or all of the customer’s needs, with solutions that may be new.

A deeper focus on fewer customers enables marketers and designers to consider customers in terms of their systems of activities that relate to multiple needs and consequences of the product or bundle of products and services. This enables the relationship between needs to be examined and thought-through to reduce trade-offs. Increasing the scope of understanding of human needs means that a greater number of stakeholders are addressed, in part, because stakeholders are actually mostly roles not separate people. For example, every human stakeholder has a physical body that is part of the ecosystem as seen in issues of health. Examples of how health issues affect customers, employees and communities will be given under ecosystems. Health consequences of products are one way to expand understandings of customers as a system and deepen the value offered to customers and create shared value among stakeholders. The customer share strategy can address multi-faceted aspects of value for customers.

Customer share is also an alternative strategy for diversification to manage risk: Whereas, conglomerates diversify across unrelated areas, customer focused strategy manages risk through better information about customers and diversifying offerings to customers. Unique packages of products as fuller solutions can make customers rely more on a particular firm.

Positioning possibilities vary by industry. Some industries are simple commodities that cannot be translated as easily into customized products and broader solutions.

Competitors

In some industries there can be a shift away from always having direct competition with more emphasis on unique customer market spaces. Competition may still be appreciated as a motivator and source of ideas as even Japanese automakers also sometimes maintain unique spaces that were more secure from competition, while maintain direct competition at the same time (Johannsen and Nonaka, 1996).

Competition and cooperation can be combined in firms that may be direct competitors in the final product markets but share resources up the supply chain through associations that train in general purpose organizational technologies like total quality control in Japan, and then total quality management and six sigma in the USA (Shiba and Walden, 2001; R. Cole, 1999).

The sustainable firm changes the conception of competition and its alternatives. The shareholder firm upholds ideas of markets and competitiveness almost as an absolute value with a variety of meanings. The influence on language can be seen in Porter’s defining theme of “competitive advantage,” even though Porter’s theory is not limited to that framework. Stakeholder firm proponents seize the opposite side of the dichotomy by upholding cooperation as an absolute value with more conscious coordination. The sustainable firm breaks out of this dichotomy with a third position, that of serving customers and stakeholders. It also incorporates both cooperation and competition, for example, perhaps having competitive debates to determine the best ideas for win-win solutions. There is a shift from competitive individualism and toward empathy to understand customers and cooperation in the collaborative supply chain.

Capabilities and Innovation

The right amount of focus on unique capabilities enables delivering value to customers that is maximum and possibly unique. While each firm can have a different strategy and combination of the three Cs, the focus here will be on the general organizational capabilities to strategize: to create knowledge, improve and innovate. This is innovation in organizational systems. Drucker states that there are strategic objectives for all parts of the organization:

“Strategic objectives are, in general, externally focused and (according to the management guru Peter Drucker) fall into eight major classifications: (1) Market standing: desired share of the present and new markets; (2) Innovation: development of new goods and services, and of skills and methods required to supply them; (3) Human resources: selection and development of employees; (4) Financial resources: identification of the sources of capital and their use; (5) Physical resources: equipment and facilities and their use; (6) Productivity: efficient use of the resources relative to the output; (7) Social responsibility: awareness and responsiveness to the effects on the wider community of the stakeholders; (8) Profit requirements: achievement of measurable financial well-being and growth.” (Business Dictionary).

Customer focused strategy emerges continuously from interaction with customers and different parts of the organization and supply chain. There is relationship between strategy, marketing, sales, design, operations and innovation. Strategy is about choosing a focus. Marketing listens to customers. Sales talks to customers to sell and to get feedback and thus join marketing in listening responsively to customer wants and needs. Innovation creates new products, production processes and customer interactions. Strategy emerges through these interactions and iterative learning about products and new customer wants and needs. Horizontal organization begins with customer interfaces at marketing, sales and service to inform design and operations. Collaborative management coordinates these cross functional interactions. All areas of the organization are a part of strategy that is customer driven and can make contributions to innovation in systems capabilities and the product itself.

Marketing and Sales: Push Versus Pull

The principle of customer focused strategy shifts the goal toward meeting the needs of the customers and away from pushing the product.

Shareholder Firm: Push Products

Marketing is traditionally about pushing products at customers as if products and profits are ends in themselves (Levitt, 1960). Marketing is taught in business schools in terms of tactics, as the four Ps: product, price, promotion and placement, rather than the end: the needs of the customer. These tactics remain important in the sustainable firm but are deployed under a customer focused strategy.

Sustainable Firm: Pull of Customers

A customer focus involves a shifting from the product to the customer, from talking to listening, from wants to needs, from selling to establishing relationships, from market share to customer share.

A customer focus ranges from listening to what customers say they want, to assessing what customers really need; from working with customers who do not know what they want, to customers who lead innovation. Customers often do not know what they want until presented with a real choice, which may change based on new options. Understanding customer needs can mean listening to what they say with active inquiry, observing their activities and lives, and being the customer to understand the experience firsthand. Each of these ways of understanding can suggest multiple interpretations of needs and solutions. Active listening involves creative empathy.

Talking and Listening

Sales are pulled by customer demand rather than pushing products at customers. Sales persons turn into marketers who listen and investigate customer needs to inform product design and distribution (Johannson and Nonaka, 1996). Integrating sales and marketing combines talking and listening, the horizontal equivalent of integrating concept and execution vertically. By listening to customers the organization becomes more responsive.

When listening or observing customers sales and marketing staff may learn that customers are a source of innovation when they modify existing products or create their own. Often customers are innovators (von Hippel et al, 2011; von Hippel, 2004, 1994). Microsoft discovered that customers were modifying software for their needs and the first response was to charge them with copyrights infringements, until product developers suggested that they allow customers to do the developers’ job for free. Sometimes customers will invent their own products as in the case of Nike founded by the famous track coach Bill Bowerman.

On the other extreme, Steve Jobs was known for saying, “Don’t listen to customers.” This can be taken to mean do not listen to all customers all the time, or accept what they want in terms of their immediate experience. Jobs thought ahead and in terms of the user experience as a user of the technology himself. His design principles like simplicity reflect a more customer centric point view. This raises the distinction between wants and needs.

Wants and Needs: Customer Solutions

A human need as distinguished from a want is something fundamental like survival, health, relationships, spirituality or career.

Needs can be thought of in new ways by considering the product as a means to an end, a solution to the customer’s problem or goal. Solutions often involve systems of activities in the context of a whole person’s life or business and require a bundle of products and services. IBM, for example, offers information solutions for business customers (Galbraith, 2005). There is an industry of design firms that innovate by more deeply understanding customers that includes firms like IDEO, frog, and Jump Associates.

The difference between want and need appears in sustainability consulting where client businesses may request help around compliance to regulations and philanthropy, while consultants may suggest what firms really need is to change their strategy. Being customer focused includes understanding the frames through which customers interpret their needs, such as, business clients framing sustainability or quality in terms of a cost-benefit trade-off, so consultants can reframe solutions for business customers in term of a new strategy and model of the firm.

Wants and needs can be translated into any aspect of value for customers: features, brand image, price, reliability, speed of delivery, service, etc. To this can be added ecologically sustainable value that takes into account the product’s life-cycle with regard to: carbon emissions, recyclability, resource renewability, waste, and toxicity. These aspects of value combined are sustainable customer value. Here are some examples of ways innovation contribute to sustainable customer value and firms profitability (Laszlo and Zhexembayeva, 2011):

- Risk aversion, for example, less toxic products and workplaces.

- Reducing waste, energy, and materials are operational gains that can be translated into lower costs and prices.

- Differentiation of products within a market

- Entering or creating new markets

- Branding

- Influence of industry standards to make the firm a leader

- Radical innovation in customer solutions, organizations, supply chains, institutions, and economies—this is systems innovation.

Listening to understand customer needs helps form relationships and occurs through relationships, which has benefits for business.

Customer Relationships and Loyalty

The new marketing builds relationships with customers as a trusted advisor (Johannsen and Nonaka, 1996). It does not seek to maximize the individual unit of the sale to make immediate sales quotas, but loyalty and retaining customers over the long term with multiple purchase and word of mouth advertising (Reichheld, 2003, 1996). One advantage is that it costs less to make additional sales to the same customers than find new ones for each sale. Another advantage is that relationships can develop more trust and communication to get feedback about existing products and find new needs to meet. This can lead to more customized products and services and higher profits under a customer share strategy, as explained above.

Customer focused relationships also apply to internal customers since horizontal organization is understood as a chain of customer to supplier links rather than separate jobs treated as private turf. This requires that the whole organization align and mobilize.

Customer Driven Organization

Most businesses that claim to be customer focused are actually product centric and consider the sale to be the goal (Galbraith, 2005). And fewer can show how each function of the organization is fully aligned to customers and not distracted by internal objectives like cost cutting, production targets, sales quotas and even market share that are not aligned to customer needs. Being customer focused does not mean simply adding on a customer relationship management program, it means transforming the organization through the new economic logic it instigates. However, there are degrees of being customer focused, relative to organizing around capabilities in the form of specialized skills and functions Galbraith, 2005). The goal of serving customers is a common goal that reorganizes the firm horizontally.

Product Design

Design shifts from pushing products out based on the ideas of designers and their technical or cost limitations, and toward customer requirements driving design criteria and forcing innovation in products, technologies, and processes of design and production. The specific issues in product design are accuracy of features in meeting customer needs, product reliability, and speed and cost of product development cycles.

Sequential Design Engineering

In a specialized organization product design may begin with internal design criteria, like styling considerations, not customer needs, as was done in the American auto industry. Then the design is passed down from general concept to more specific design features, production engineering, and finally to operations, in a sequential manner with each step being completed to optimize efficiency of each work unit. Problems with the previous stage of design in term of how compatible it is with other components, materials or manufacturing are only discovered later after much time has been invested, and then things need to be redone or a sub optimum design is modified enough to be forced through to get product out fast. As a result, often more time and therefore money is spent on a less reliable product that may not be fully what customers want or need, making the product an end in itself to some degree. Thus, under this system of sequential design engineering based on unit efficiency there is a trade-off between costs and quality.

Concurrent Design Engineering

In the sustainable firm the process of concurrent design aims for greater accuracy in meeting customer requirements through collaboration with everyone concurrently, more or less, at each stage of design so that customer specifications can be clarified (Ward, et al, 1995).

Marketers and customers provide input about customer needs through interaction. Customers and can also participate in product design in various ways, especially if they are businesses. Customers can participate in design of products through open innovation processes in which companies actively solicit input and participation from on the internet, for example. The open source software of Linux is the classic example of customers being co-producers as well. Some industries lend themselves to employees being users or customers as well: Google and Apple employees are also customers of their own products by using the technology themselves.

The process of collaboration is more responsive to customers by providing more immediate feedback for clarification of requirements and implications for each aspect of design for selection of materials, whether one part will fit with another, or whether it can be manufactured realistically. Design for manufacturing is also called “robust design” that tolerates variation in size of parts, for example, for ease of manufacturing without defects. Iterations to modify designs occur sooner to prevent problems before concepts are turned into full designs and materials committed. This saves time in the long run. Earlier feedback leads to shorter iterations and allows for more revisions, if necessary (Ward, et al, 1995). This involves feedback sooner than after production and distribution if fuller underway. Prototype testing creates models of parts or the full product to share with downstream designers or customers. In the field testing with the first versions of the product further gather feedback.

Concurrent engineering design cycles are shorter, less costly, more reliable and more accurate, and thus reduce trade-offs (Womak et al., 1990). This is achieved by reducing waste and delays to simplify processes and the system as a whole for economies of simplicity.

Product design embodies all nine principles beginning with creative empathy to understand and design solutions for customers. Improvement of design processes pays careful helps create economies of simplicity to reduce trade-offs between time, cost and quality, using root cause analysis of problems, such as, communication in horizontal organization. The result is systems innovation that is more responsive to customers.

The same principles of customer focused collaboration for immediate feedback and preventive quality control are also applied to lean production.

Operations—Lean Manufacturing

Operations encompasses manufacturing, services and a range of basic work processes In a supply chain that serves customers. Operations shifts from pushing products or services based on the internal logistics and financial goals of firms, to being driven by immediate customer demand and specific needs that are translated across tasks and functions of the firm horizontally, known as “market-in.”

Mass Production

The shareholder firm, as well as the privately held early Ford Motor Company, has been linked historically to the principle of specialization in mass production, specifically, economies of scale. This system worked well as a continuous flow of production from crude iron ore to a finished automobile until the 1950’s. The problem arose when there was customer demand for a variety of products and the machines needed to be modified to make different models or features. Then the smooth flow of the system was interrupted and it became so complex that the focus shifted to maximizing individual units.

Mass production under a variety of products starts with the internal objective of creating efficiency of each work unit hoping that the whole will equal the sum of the parts and that customers will be happy. However, by starting with the individual work unit, mass production organizes around efficiency and then loses sight of the end of producing for customers. Without an end in sight, there is little basis for organizing means with feedback from an end point to guide improvement. As a result, efficiency suffers for the units and the whole system.

Unit maximizing in manufacturing begins with each machine being run as fast as possible in large batches for the efficiency of the machine. This creates four major problems.

Defects in parts and finished products accumulate before they can be inspected, wasting more material. Inspection is an additional job, not something that operators do, which takes more time. The way this system is designed presents a trade-off between quality and cost: more inspection and rework is needed to improve quality, costing more.

Another problem arises if a variety of products are required or customized features because machines are often not very flexible for making different features, sizes, or models so it takes time to adjust and modify the machine for another model–this is known as the machine change-over time, which could be 24 hours. So machines are run fast for a higher level of volume to make machine use efficient and avoid long change-over times, and this is weighed against the cost of the inventory of output that needs space for storage—a ratio called the economic order quantity. The ratio reflects trade-offs built into the system that follow from inflexible machines and the objective of optimizing machines as single units.

A third problem results from the first two: higher complexity and more space needed for inventory of parts or work in progress that is waiting between worksites due to delays from defects and long machine change-over times. In fact, extra inventory may be held as a buffer against defects and delays upstream, for “just-in-case” production. With inventory, there are longer distances between stations needing more time to move it.

Fourth, production is run by internal efficiency metrics instead of demand by customers, often resulting in inventory of finished goods that increases the costs of real estate and capital and that may need to be dumped at a discount.

In summation, the design of this system is generally overly complex since the system is designed as a collection of parts, not a coherent whole. With inspection after the fact, it lacks processes of improvement to align to customer need.

Lean Production

The sustainable firm’s lean production does the opposite of mass production pushed by efficiency of work units: it is pulled by customers and maximizes work flows across the whole system. Lean production is also known as the Toyota production system or the just-in-time, JIT production. “Lean” means with low inventory and other forms of simplification of complexity (Liker, 2003; Bowen and Spear, 1999; Womack and Jones, 1990; Ohno, 1988). Its logic begins with the pull of customers: to create value for customers by giving customers what they want, when they want it, reliably for good value.

Customer demand pulls lean production in a horizontal organization consisting of customer to supplier links. Lean production in pure form begins with producing only for immediate customer demand to customize orders—Dell computers is an example of this, after being pioneered by Toyota in Japan. Lean production operates with minimal inventory for delivery of parts just-in-time for the next work station to utilize without delay. In order to achieve this, it must prevent delays from defects, machine rigidity, and general complexity. The method is total quality control to analyze root causes and improve and control processes.

The process of control and improvement is driven by metrics at each work station that are related to customer requirements: the latest order with its specific features, provided without defect or delay. These are the ends that are used to measure and control the means / processes. In this manner, customers drive the system.

Customizing products requires flexible machines that are easily converted for different features, sizes, colors, etc. Machine change-over times have been reduced from as much as 24 hours to a few minutes, or can be automatic for everything from autos to cell phones. Fast change-over times keep the flow of production moving to minimize inventory.

Quality is improved by detecting defects immediately and designing reliable processes. Defects can be detected by self and local inspection, including automatic inspection by each machine. Some machines have an alarm with lights and can shut down automatically. Anyone can pull a chord that shuts down the assembly line. Then the problem gets total attention from the workforce. When operating with little inventory, any delay affects the whole line immediately since the next worksite is waiting for that part to arrive so there is built-in incentive to prevent delays. There is less clutter and it becomes easier to inspect work from a previous work station, one piece at a time, for more immediate feedback and rapid correction, for a virtuous circle or positive feedback loop that improves reliability and speed, and, therefore, costs.

The complexity of the system can be further simplified by reducing the number of tasks and procedures, along with the distance between work stations. Simplicity improves speed by enabling production to flow non-stop between work sites in a careful and deliberate manner, not as a reckless speed-up of individual machines in an unbalanced factory layout. To achieve continuous flow production, all processes must be improved at a similar rate for balance; otherwise the slower processes will hold back the system as they all feed toward the final finished product. This is another reason why continuous improvement is implemented as “total quality” by everyone.

Lean production is a form of systems thinking that has inspired manufacturing, construction, and services such as Southwest Airlines (Hoffer, Gittell, 2003). Even hospitals study Toyota’s lean production methods where the central challenge is to coordinate the many specialties around the patient. “Relational coordination” between specialist care givers requires communication that is frequent, timely, accurate, and aimed at problem-solving rather than blame (Hoffer-Gittell, 2009). Services require cross functional processes that can be like both concurrent product design and sequential operations, since work might be re-planned as needs emerge.

Lean production can be summarized as a system pulled by immediate customer demand in continuous flows with minimal delay and inventory using principles of simplicity, flexibility, reliability by design, and immediate feedback for correction, prevention and improvement. It is designed according to principles of the sustainable firm: the organization is more responsive by using customer focused criteria to drive internal process improvement, using root cause analysis, to create economies of simplicity that reduce trade-offs. The result is innovation of the system: horizontal organization driven by customers.

The major functions of sales, marketing, design and operations are the substance of horizontal organization. Management and staff functions are designed to support these functions that directly create value for customers. That is why it became popular to invert organizational charts and put managerial hierarchy below the value adding functions.

Management: Collaborative Policy Development

With customer focused strategy management shifts to supporting functions that respond to customers, rather than driving objective down the chain of command and out toward customers. To do this, there must be a shift in the basic beliefs about management, a shift from controlling people to improving systems responsiveness toward customers.

One of the most basic choices managers make is whether to define problems in terms of people or in terms of systems. More commonly in the shareholder firm managers blame individuals and assume that the problems are opportunism and individuals’ inherent limitations and inabilities to learn. In the sustainable firm, on the other hand, systems are largely to blame and it is the responsibility of management that designed the systems that shape the behavior of individuals within the system. The problem of systems includes complexity and uncertainly about unpredictable environments, customers, and competitors. Uncertainty requires systems to be more responsive, instead of attempting to create predictability through controlling people. Controls shifts to designing systems that prevent problems and can respond to change. The differences between these systems of management are worth explaining in detail.

Remote Control Management

The shareholder firm often has a command hierarchy concerned with limiting the abuse of authority of managers or office holders, and the opportunism of those below them. The shareholder firm is concerned about the potential selfishness of managers that do not act in the interests of owner-investors (Jensen, 2000). With financial goals, the shareholder model of the firm relies on financial metrics to monitor progress and provide accountability externally. Financial metrics are a key tool in the command hierarchy of the shareholder firm, known as “remote control,” through managerial accounting (Johnson and Broms, 2000; Kaplan and Johnson, 1987).

Remote control links the financial accounting used to report externally to financial markets, with management accounting internally to run the business. While it is well known that financial markets can exert short term pressure for financial returns on firms with destructive consequences, the deeper issue is that financial metrics neglect causes and results for customers. Financial metrics are used for cost control as if costs are causes; but costs are not causes, costs are one kind of result of processes and systems. Remote control reveals little about customers or causes of costs.

Remote control accounting is focused at the wrong level of separate units and categories, rather than total cost. It focuses on separate units with categories like detailed job step reporting, labor reporting, direct versus overhead costs, fixed versus variable costs, marginal analysis, and units of productivity for labor and machines. These categories can lead to accounting games and lose sight of total costs, causes, and customer satisfaction. For example, to control spending and reward productivity, managers are rewarded for low overhead costs as a percentage of production volume. So the easy solution is raise production whether there is demand or not. The result is excessive inventory, which raises costs, and products that may have to be dumped at a discount. These accounting and production scheduling games are not aligned to revenue from customers nor examine the total cost involved.

Remote control accounting based on standard cost accounting and finance has been considered the single biggest set of barriers to transforming organizations as observed in cases of total quality management, a movement that as a whole experienced limited implementation with many distortions (Hess, 2006; Grant et al, 1993).

The problem is even larger than just using financial numbers, there is a lack of management processes. Even when manages try to implement programs other than remote control, there are four fallacies in command hierarchy that surface, as identified by Deming (1993, 1986).

Management by Objectives occurs when managers declare objectives without detailed implementation of processes to get results. This is based on the separation of concept and execution in work design. In business this is often described as a failure of leadership and failing to walk the talk, yet these criticisms are still in terms of individual qualities rather than systems. Although command hierarchy is thought of as overbearing and too much organization, it is actually not enough organization because it lacks management processes.

Management by Results means that managers measure outcomes in terms of employee performance but do not analyze or understand the causes beyond individual performance. A control structure that sees people as the problem does not analyze systemic causes.

Costs are causes. Managers often talk about costs as if they are causes and then try to cut the quantity or price of inputs—but that is a limited option. Actually costs are one kind of outcome. Real causes of business performance are processes that utilize inputs, relationships, technology, and the design of systems.

Reactive Management is a consequence of the first three problems. Managers, boards of directors, and investors react to the latest data point and attribute results to an individual’s performance, rather than using data to assess statistical variation of systems outputs and analyze root causes. For example, a firm’s costs may rise and profits decline when a major product development cycle begins and this could be interpreted as a decline in performance by investors who lack information (Johnson and Broms, 2000). Crises are often handled with blame, firing, and hiring a new manager promoting a new fad. Boards or manages often jump to solutions without understanding the cause of a problem.

The alternative form of management focuses on causes in systems rather than individual results.

Collaborative Policy Deployment

In the sustainable firm the management process identifies the challenge as making organization more responsive to unpredictable environments and managing systems complexity internally. These challenges require creating knowledge to improve processes and support innovation. The more people collaborate, the more knowledge is created about customers, systems and possibilities. Collaboration is necessary to acquire context specific data and tacit knowledge from work sites and customers to plan for detailed implementation. Management becomes a process rather than a position. Collaboration also serves to forge consensus around strategy and implementation and through emotional “buy-in.” What makes decisions legitimate is not formal authority of positions or contracts but evidence upon which decisions are based. The new principle is “management by fact” about how processes serve customer needs. Decisions based on data generated by associates anywhere in the organization can trump authority based on position. The term management by fact was popular in the movement for total quality management, now known as six sigma, which provides methods for process improvement and innovation.

Collaborative processes often involve spiraling conversations up and down hierarchies and across functions (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). A thorough model of collaboration has been standardized in total quality management’s process of management known as policy deployment, or Hoshin management, aimed at implementing plans for breakthroughs (Shiba and Walden, 2000). Planning discussions occur up and down the hierarchy with questions like, “If we agree on this goal, what would you do?” This process can evoke more ideas and data about customers and process capabilities to set realistic goals for improvement. Policy deployment results in detailed implementation made explicit in Hoshin improvement matrices for each job that state the goal, means, targets, and data tools to measure progress.

Planned follow-up to monitor implementation is conducted by managers at different levels to support employees in detailed implementation through regular audits in which even the CEO can visit local worksites to hear presentations. There must be more positive comments than negative ones from managers who also make sure their body language is positive. People are praised, not punished, for finding problems with systems that can lead to improvement. Problems with implementation are met with more resources for improvement. There is also the possibility of receiving feedback to change the course of strategy through this iterative process, especially with feedback from sales and marketing about customer experiences. Success stories are gathered and solutions shared where applicable. In addition, management ideally also improves its own processes of coaching people and continuously improving the organization for breakthroughs (Greene, 1993).

There are cultural differences around how much time to take to reach consensus and have everyone clear on customer requirements from the beginning, with American firms tending toward the side of making fast decisions with weaker mobilization of the whole workforce. In fact, policy deployment is noticeably absent in the newer six sigma that superseded total quality management, and instead emphasizes training specialists up to the level of “black belt.”

Under collaborative policy deployment formal authority still exists, but recedes into the background as managers become responsible for facilitating discussions and holding decisions accountable to the standards of management by fact. Final decisions may still be theirs, but the process is collaborative.

Policy deployment under management by fact uses simple scientific methods explained next. These methods are also used at specific worksites for process improvement.

Process Improvement

Management as an activity means that each worker is involved in managing specific work processes, organizational transformation, and strategizing as in policy deployment. Collaborative management involves combining concept and execution at three levels: self and local inspection for quality control, reactive process improvement, and proactive improvement or innovation. Customer needs drive all three levels. Self and local inspection responds to results of one’s own work that one observes or by receiving feedback from the next in line customer’s criteria for receiving the part or product, and this can instigate reactive process improvement. Proactive improvement is planning larger changes, and can involve doing deeper customer research, beyond what is heard in routine interaction with customers. These methods can be used by teams of shop floor or frontline service and sales forces.

Basic processes for control and improvement have been standardized by total quality management and six sigma and consist of simple scientific methods to measure results for customers and analyze causes in processes. These methods can be used continuously for controlling quality and for continuous process improvement. TQM’s essential process is the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle, PDSA, while Six sigma has two different cycles with the same basic logic: DMAIC and DMADV, explained immediately below (Pande, et al. 2000).

- Plan, (define problem, gather data, analyze data, formulate solution) Do, Study, Act

- Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. (for an existing process)

- Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify. (for a new process or product)

These processes begin by defining a problem to solve in a way that is measurable, gather data, analyze root causes, generate solutions, measure the results, and repeat the cycle or institutionalize results.

Data gathering and analysis can involve statistics that are used inductively and empirically to assess the type of statistical variation of a system that indicates whether the causes of the problem are due to the design of the system or individuals within it (Deming, 1993). The rule is that 85% of problems are caused by the systems that management designed, and are thus not a problem of opportunism or mistakes, but of social structure. This kind of statistical analysis is part of scientific methods that makes work an iterative experiment for continuous improvement. Experimentation can provoke reflection on existing premises for deeper innovation. Applied statistics is focused on empirical results, not driven by math and academic hypothesis testing.

One objective is to reduce variation in work processes and outputs since variation creates defects. Having routine standards is the first line of defense against the “enemy” of variation (Deming, 1993). Variation in the output of a system refers, for example, to slight variations in the size of parts. A part that is too small or large would be considered a defect when it does not fit together with other parts when assembled. It is also beneficial to reduce variation beyond minimal specifications because it can improve reliability and performance for the customer; for example, when variation in the size of moving parts is reduced, there is a tighter fit and less friction and wear. In fact, reducing variation quantitatively can also turn into a qualitative leap in product performance as in the case of Toyota’s Lexus luxury car line, which established its luxury feel from its smooth and quiet ride by reducing variation in the size of parts of the engine and other moving parts to reduce friction, vibration and noise. This is how even quality control can lead to innovation.

Process improvement is a core purpose of collaborative management. All nine principles are seen in collaborative management: process improvement using root cause analysis implemented organization wide creates systems innovation as a new form of organization designed for economies of simplicity to reduce trade-offs. This starts with managers being responsive in supporting employees that are serving customers. Creative empathy is central to collaborative work.

Managers need new non-financial accounting metrics to shift from traditional cost control to quality control, process improvement, and customer needs. Managing this system requires new metrics from accounting to align all the parts of the organization to serving customers.

Lean Accounting: Customer Based Metrics

The new “lean accounting” of the sustainable firm starts with customer focused metrics and their real physical causes of outcomes for customers, with total costs of the system being more important. This shifts away from the shareholder firm’s accounting that often measures costs on a per unit basis in more detail, without looking at causes and outcomes for customers.

In lean accounting accountants can become change agents by helping people to understand the roles of new metrics in a new organization (Stenzel, 2007; Johnson, 2000; Maskell, 1996). Lean accounting supports the metrics used in lean production—for customers and causal processes. The financial aspect of managerial accounting is simplified into general figures like total cost of sales and budgeting at aggregate levels. As a result, accounting departments are leaner by cutting up to 90% of activity that is wasted on monitoring people for potential opportunism and is an expression of mistrust in the organization (Maskell, 1996).

The difference with lean accounting begins by disconnecting managerial accounting from financial accounting and financial markets to, instead, align managerial accounting with customers. Focusing on customers leads to choosing concrete metrics that reflect causes in production. First are metrics of outcomes for customers like customer satisfaction, loyalty, retention, lifetime value of a customer, customer share, and customer share of most valuable customer (Vandermerwe, 2004, 2001). Aspects of value for customers include reliability, price, and speed of delivery. Customer value translates into internal performance metrics like defect rates, cycle times, machine change-over times, which all reflect the degree of complexity or simplicity of the organization, and thus, economies of simplicity.

Accounting can also expand to other stakeholders. Key performance indicators may also include employee safety, absenteeism, health, energy efficiency, and carbon footprint. These new metrics fall under the new “triple bottom” line of financial, social and environmental introduced by the stakeholder firm that can be utilized along with a customer focused strategy. In fact, all these metrics impact customers because stakeholders are actually roles: everyone can be a customer, employee, investor, and part of the community and ecosystem.