Otto Laske

Otto Laske

In this text, I focus on the central relevance of interviewing skills in being able to lead a dialog in the structured way made possible by the Constructive Developmental Framework (CDF), whether it be social-emotional or cognitive. I do so in the context of showing that the certification as a Master Developmental Consultant/Coach at the Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM) is not based on “developmental theory”, but rather on a discipline derived from it by me, namely, a dialogical and dialectical epistemology. Developmental theory per se is taught in applied courses which serve as a basis for learning CDF epistemology, and in this sense are mere teasers for learning to think and listen developmentally, dialogically, and dialectically.

Abbreviations:

CDF = Constructive Developmental Framework (Laske);

DCR = Dialectical Critical Realism (Bhaskar);

DSF = Dialectical Schema Framework (Basseches);

DTF = Dialectical Thought Form Framework (Laske);

IDM = Interdevelopmental Institute (Laske).

Social analysis can learn incomparably more from individual experience than Hegel conceded, while conversely the large historical categories, after all that has meanwhile been perpetrated with their help, are no longer above suspicion of fraud. …The individual has gained as much in richness, differentiation, and vigour as, on the other hand, the socialization of society has enfeebled and undermined him. In the period of his decay, the individual’s experience of himself and what he encounters contributes once more to knowledge, which he had merely obscured as long as he continued unshaken to construe himself positively as the dominant category.

Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia

When I started writing my two books on Measuring Hidden Dimensions in 2005, it was clear to me that the most progressive part of Kegan’s and Basseches’ theories is found in the empirical interviewing methodology they based their theories on (and have remained very silent about ever since). Rather than engaging primarily with the abstract concepts these theorists put forward, what interested me primarily was how through an interviewing dialog evidence could be gathered about individuals’ and groups’ present way of meaning and sense making.

What I saw as the gold of developmental theory, namely the interviewing required to obtain developmental evidence by listening to individuals, laid buried until CDF came into being in the year 2000, and still remains buried for the majority of developmental practitioners after 15 years, because of the huge amounts of “theory” and ideology that have been heaped upon Kegan’s and Basseches’ conceptual interpretations of their interview-based empirical findings.

The unique reading of mine of both theorists (who were my teachers) derived from several different sources: my being a composer and musician; my schooling in dialectical philosophy in the 1960’s and in psychological protocol analysis (H. Simon) in the 1970’s, the organizational interviewing I practiced as member of a big US consulting firm (ADL) in the 1980’s, as well as my training as a clinical psychologist (Boston Medical Center) in the 1990’s.

As a result of my training in these various modes of dialog with clients and patients, in my two books I moved, I would say today, from developmental theory to a new kind of epistemology (theory of knowledge), one that is based on dialog and thus has the potential of becoming a broader social practice, in contrast to argument-based dialectical epistemologies such as Adorno’s and Bhaskar’s which put themselves at risk of remaining elitist.

In this short paper, I want to highlight some of the outstanding features of this transition from “developmental theory” to dialogical epistemology. Eventually, this transition allowed me to bring together the main tenets of the Kohlberg and the Frankfurt Schools, something nobody had attempted, or stumbled on, before.

–––––––––––––––––

While others read especially Kegan’s, but also Basseches’ work, for the sake of constructing either abstract or applied theories of adult development (most of all Wilber who designed a hermeneutic philosophy based on Kegan’s non-empirical work), I was most impressed by the qualitative research they had done on individuals, for the sake of explaining how adult consciousness develops over the life span, and also, why the movement they discerned has a huge impact on how people deliver work in the sense of E. Jaques. I found myself aiming for a new theory of human work (capability) that would go beyond Marx (who never thought about the internal workplace from which work is delivered (Laske, 2009).

In focusing on interviewing and the scoring of recorded interviews (which I always saw as a unity), I implicitly took to heart what is conveyed in my teacher Adorno’s quote, above, in which he basically says that rather than be guided by abstract concepts about development (such as “stages” and “phases”), deeper insight can be gained by delving into the frames of mind of individuals. Given my psychological training, I thought that the main issue in teaching CDF-interviewing as a dialog method would lie in making clear the separation between the focus on “how am I doing” (psychologically) and either “what should I do and for whom?” (social-emotionally) or “what can I know about my options in the world?” (cognitively). This triad of questions for me encapsulates the mental space from within which people deliver work, without ever quite knowing how to separate them in order to reach a synthesis of self insight.

––––––––––––––––

Serendipitously, I got to know Bhaskar’s work just at the right time, in 2006, when I was in the midst of writing volume 1 of MHD and preparing for volume 2. Reading his “Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom” (1993) challenged me to reflect on the DTF-dialectic I had been teaching, but also to reflect on its relationship to my teacher Adorno’s work. Although a declared enemy of ontology which he accused of sealing the oppressive status quo of capitalist society, Adorno had viewed social reality, as well as the human mind, as intrinsically dialectical. He demonstrated that view in the analysis of musical works, but also through philosophical text analysis in both of which he was a master.

I noticed right away that Bhaskar’s MELD, the four moments of dialectic, were not only a step beyond Hegel and Adorno, but also equivalent to Basseches’ empirically derived and validated four classes of thought forms, and that Bhaskar’s ontology was only feebly developmental and epistemological, especially in his theory of eras of cognition and types of epistemic fallacies.

I began to see that, from Bhaskar’s vantage point, the CDF-based cognitive interviewer was centrally dealing with “epistemic fallacies” and “category errors” committed by people in organizations, and that the interviewer’s task was therefore to “retroduce” these errors, that is, show them to be fallacies by interpreting what was said by the interviewee and then enacting DTF, the Dialectical Thought Form Framework.

Cognitive interviewing constantly encountered THE epistemic fallacy according to which the world is reduced to what is presently known about it, with the benign neglect of pervasive absences. Taking further into account Bhaskar’s distinction between the real, actual, and empirical worlds, I began to see that individuals who could not rise beyond this fallacy, and thus could not transcend the actual world – what the real world appears to be, rather than what it is – were surely stuck. In the CDF framework that also meant that they were not as effective at work as they could be as social-emotionally aware dialectical thinkers.

Bhaskar’s ontological postulate of four moments of dialectic, once it was viewed in terms of Basseches’ Dialectical Schema Framework (DSF; 1984) meant that a trained CDF-user could through empirical inquiry (interviewing and scoring) help such individuals move from the actual world –the world of TV and of downloading – to the real world in which problems like organizational survival and global warming have to be solved.

So, while Bhaskar really had no good tools for dealing with the language-suffused world of organizations and with global issues requiring action in a concrete and effective manner, I more and more came to see CDF not only as an epistemology, but also as a set of dialogical tools – whether social-emotional prompts or dialectical thought forms — ready-made for intervention in organizations and institutions for the sake of culture transformation and related strategic goals. This was an obvious realization since the interviewees in IDM case studies were mostly executives representing organizations of various sizes.

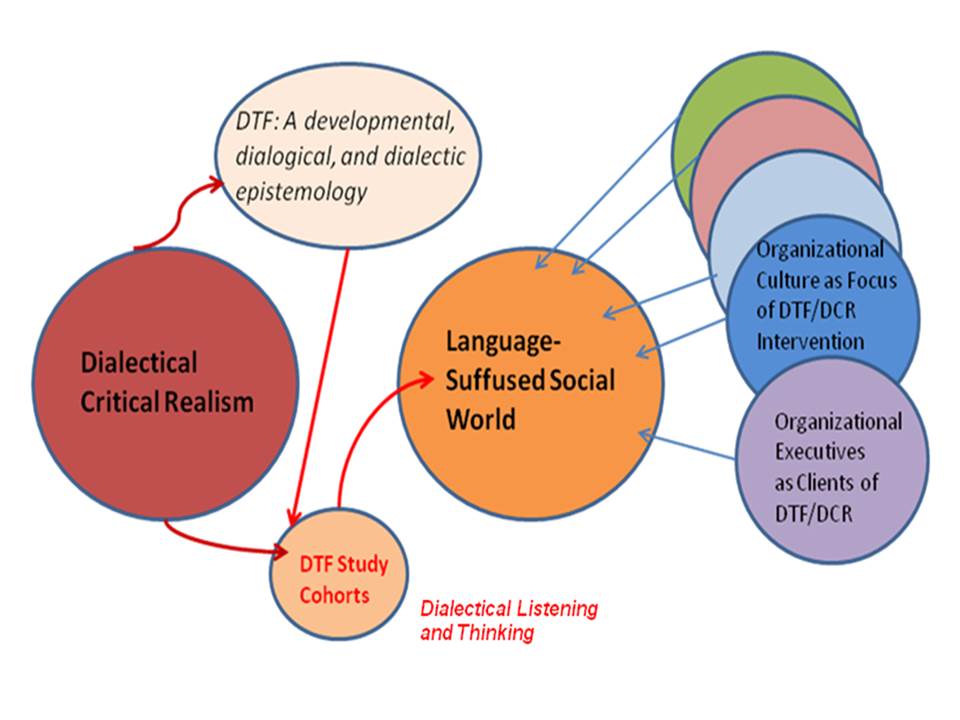

For this reason, in a conference presentation devoted to Bhaskar’s work in London this year, I proposed that his “dialectical critical realism” (DCR) could (or even needed to be) enhanced and concretized by CDF/DTF, as shown below:

Figure 1.

As shown, I see IDM study cohorts whose members graduate with 3 case studies (and in the future also with a team project) as engaging with epistemic fallacies and category errors committed by executives and their teams, and suffering accordingly. By way of their interviewing and scoring skills such graduates know (“can hear”) what in the language-suffused world of organizations needs to be transformed, for these organizations to survive or thrive in an ecologically reasonable way.

Following Brendan Cartmel’s work in CDF-based socio-drama, I began to refer to CDF users as inter-developmental interlocutors. By this I mean that they are educated as developmental and dialectical thinkers simultaneously, and thus are able not only to spot how client are presently making meaning and sense of their world, but also are able to assist them in moving from the actual world they are submerged in into the real world which they only dimly seeing.

My definition of inter-developmental interlocutor is that s(he) is one:

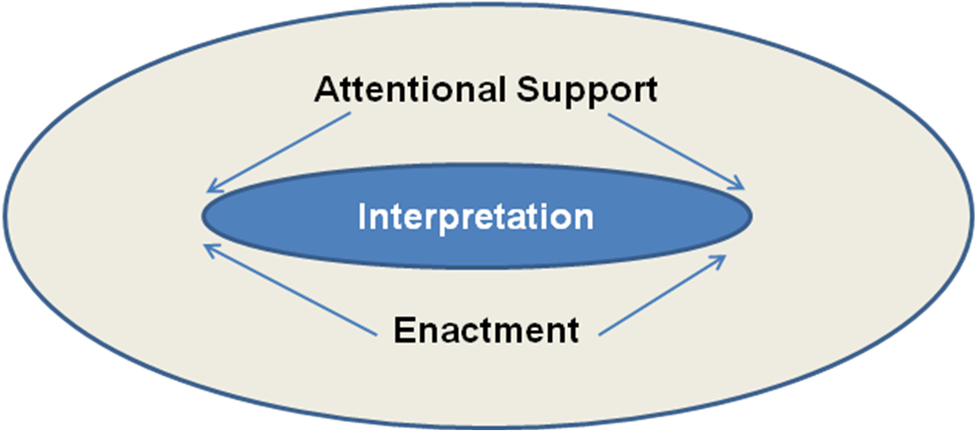

Learning from the later Basseches, now speaking as a theorist of psychotherapy in its diverse modes (Basseches and Mascolo, 2010), I began to understand that what I was teaching my students, and was myself doing better and better in my own coaching and work with teams, was based on consciously separating three dialog modes, shown below:

Figure 2

Basseches and his co-author show in their 2010 “Psychotherapy as a Developmental Process” that all psychotherapies are based on the selective privileging and coordination of three distinct dialog modes, and that psychotherapies differ in their emphasis on one or the other mode.

In my view, the authors thereby also point, at least indirectly, to coaching and consulting, — other forms of dialog used in the language-suffused world. I would give the following brief definition of these modes of CDF-based dialog:

- When giving attentional support, the CDF-interlocutor is focused on listening to the client, conveying deep interest in what is on his/her mind, and if need be reinforcing the client’s feeling and/or thinking. No CDF interview can be done without this support, nor can any feedback or any other consulting be engaged with. Attentional support is also, I would say, the primary mode an interlocutor uses in any social-emotionally grounded consulting activity. But clearly, this mode is supported, even in dealing with meaning-making only, by interpretation, and in coaching possibly by enactment (e.g., modeling a “higher” stage of meaning making).

- Interpretation is a broad field, since one can interpret moods, feelings, thoughts, frames of reference, ideologies, category errors, epistemic fallacies, almost anything expressed through speech, as well as text. So what is meant? Cleary, social-emotional interpretation differs from psychological and cognitive interpretation, and these differences are exactly what students are learning at IDM.

In contrast to the social-emotional interview, the cognitive interview is focused on interpreting base concepts, not factual content or feelings. We can interpret clients’ concepts or lack thereof in terms of DTF, and use thought forms as mind openers and mind expanders, to broaden interpretations clients propose. We do so in order to deal with client’s category errors (e.g., switching them from context to process) and epistemic fallacies (e.g., pointing out that the world is not equivalent to what the client knows about it). In this endeavor, attentional support as well as enactment support interpretation, the latter by leading clients from thought to action, “enacting a concept” (which could be a strategy) in the real world.

- Enactment is the modeling of how a concept or interpretation, a higher social-emotional stage and a modified psychological disposition can be achieved by a client. The way enactment is used social-emotionally, psychologically and cognitively differs, of course. By pointing clients to the financial or other consequences of specific strategic alternatives, Jan DeVisch, whose focus often is on enactment, has demonstrated that enactment can easily become the central mode of a dialectically oriented consulting to executive teams, especially when it is skillfully supported by the other two modes (Jan DeVisch 2010, 2013; . http://interdevelopmentals.org/publications-Jan_de_Visch.php).

It seems to me that in terms of the distinction between these 3 modes, social-emotional and cognitive interviewing based on CDF have their own idiosyncratic structure. Social-emotional interviewing is largely focused on giving attentional support to the way the interviewee selects and interprets so-called prompts, while cognitive interviewing, when done well, is based on the enactment of Bhaskar’s four moments of dialectic (extensible to individual dialectical thought forms). In both cases, the remaining two modes of interviewing dialog serve as obligatory supports for the privileged dialog mode.

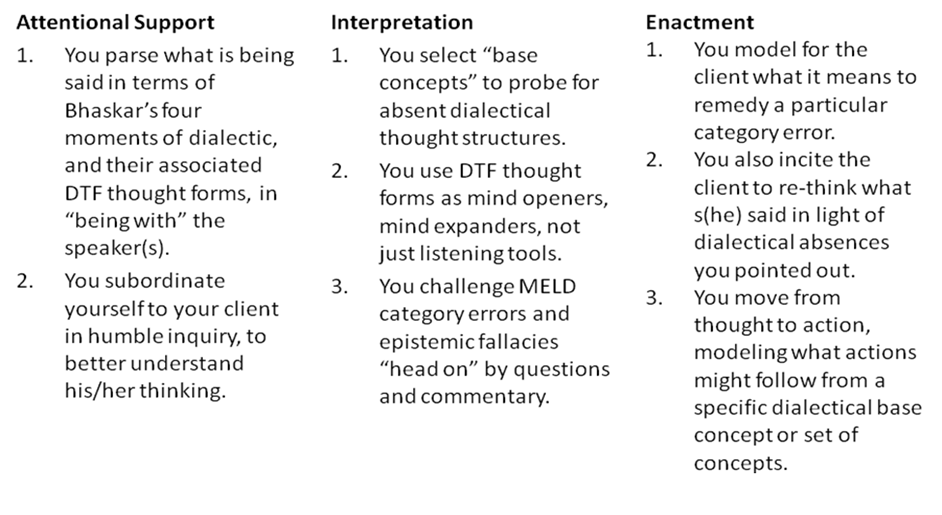

If we think about what it means to use DTF in these three complementary modes, I think it would look as shown below:

Figure 3: (MELD is a reference to Bhaskar’s four moments of dialectic, corresponding in CDF to CPRT).

Clearly, every CDF-interlocutor, when consulting to clients or coaching them, uses these three modes in a different relationship with the other two: some interlocutors prefer attentional support as the primary mode (e.g., those who only use Kegan), while others will focus on interpretation (following DTF) or use enactment in psychological or strategic feedback.

What dialog mode an individual prefers to use in his or her work, as well as in coaching or consulting, is both a psychological and developmental issue. An immature individual will be incapable of lending others attentional support, having nothing to go by than his or her ego-centrism or “competence”. Such a person will feast on a narrow set of ideological concepts, perhaps with religious fervor, and will indulge in a kind of enactment that is poorly supported by humble inquiry and attentional support. To experience the “tell and do” world in which most professionals live, you just need to listen to members of a start-up company.

–––––––––––––––

The three intervention modes outlined above also contribute to a meta-theory of coaching, whatever the approach of the coach may be, NLP, ontological, ICC or ICI. These modes help characterize “coaching schools” by the predominant dialog mode they teach. These modes are also central in team coaching and group hosting, which can be especially effective when based upon insight into the deep social-emotional structure of a particular team or cohort outlined by the CDF team typology (http://interdevelopmentals.org/team_maturity.php).

For instance, in an upwardly divided level-2 team where most team members are at Kegan-level 2 and a minority is a Kegan-level 3, enactment is powerless without attentional support, and DTF interpretation is most likely fruitless. Whereas in a downwardly divided level-5 team, where the majority of team members acts from Kegan level 5 and a minority from Kegan level 4, both social-emotional and cognitive interpretation are powerful tools to which the other two modes can be subordinated. Here, the enactment will largely come from the team itself since its task process is no longer overwhelmed by the developmentally rooted assumptions structuring the interpersonal process, as in immature teams and cohorts where “relationship” is king and defenses abound.

Doing justice to CDF as an epistemology based on dialog, not argument, is grounded in knowing what dialog mode one is presently using, when to use which mode as well as when to switch from one mode to another in a real-time situation. Being conscious of what mode one is using at any time is actually the only way of skillfully subordinating the two remaining modes to the one presently employed, something that is best learned through social-emotional and cognitive interviewing (http://interdevelopmentals.org/certification-module-a.php and http://interdevelopmentals.org/certification-module-b.php).

––––––––––––––––

There is, of course, a risk to be aware of, namely that of slipping from dialog into argument, as the “tell and do” world in which we live constantly tempts us to do. By doing so, you change your epistemology. You are now the one who knows it all. But as you also know, you can’t change the world by way of arguments (which are always only right or wrong, omitting absences, and thus pinned to the present.) If you think about it, the three modes outlined above are the three pillars of any dialogical epistemology, in whatever discipline and for whatever purpose it may be used.

Clearly, you want to meet your client where your client is since other ways of meeting don’t exist. On the other hand, your client wants to be “understood” by you by way of dialog with him or her. To “understand” professionally, you need a dialogical epistemology putting asking over telling, and if this epistemology is going to be developmental and dialectical as well, you need to learn what Kegan stages and phases of dialectical thinking empirically “sound like”. And this, again, can best be learned from developmental interviewing as originated by Kegan and Basseches, and today taught at IDM.

The more mature the client you are dealing with is, whether it is an individual or a team, the less you will have to focus on the interpretation of meanings and feelings, but rather will have to deal with concepts, or lack thereof (in the client’s speech). That means you need to have an understanding of Bhaskar’s four moments of dialectic, in CDF concretized and extended by way of dialectical thought forms.

If you can embrace all that, as you begin to learn to do in an IDM case study, you have become what I call an inter-developmental interlocutor. To arrive at this destination, “sweat comes before virtue”, as Hesiod says. You need to want to sweat it out.

Selected Bibliography

Adorno, Th. W. (1974; 1951). Minima Moralia. London: Verso.

Bhaskar, R. (2002). Reflections on MetaReality. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, R. (1993). Dialectic: The pulse of freedom. London, Verso.

Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development.

Basseches & Mascolo (2010). Psychotherapy as a developmental process.

London: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Jaques, E. (1989). Requisite organization. Arlington, VA: Cason Hall & Co.

Laske, O. (2014a). Laske’s Dialectical Thought Form Framework (DTF) as a tool for

creating integral collaborations: Applying Bhaskar’s four moments of dialetic to

reshaping cognitive development as a social practice. Conference paper, IACR,

London, July 2014.

Laske, O. (2014b). Teaching dialectical thinking by way of qualitative research on

organizational leadership: An introduction to the Dialectical Thought Form

Framework (DTF). Conference lecture IACR, London, July 2014.

Laske, O. (2009). Measuring Hidden Dimensions: Foundations of requisite

organization. Medford, MA: IDM Press.

Laske, O. (2005). Measuring Hidden Dimensions: The art and science of fully

engaging adults. Medford, MA: IDM Press.

About the Author

Otto Laske is a developmental psychologist, coach, management consultant, and coaching researcher. As Director of Education at the Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM), he guides the oldest evidence based coach and teacher education program in North America. As Director of IDM Press, Otto has published two volumes on adult development, one in 2005 and one in 2008: Measuring Hidden Dimensions: The art and science of fully engaging adults, IDM Press, 2005 (2nd edition 2010), also available in German and shortly in French and Spanish and Measuring Hidden Dimensions of Human Systems: Foundations of requisite organization, IDM Press, 2008.Otto was educated at Goethe University, Frankfurt (studies with Th.W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer) and Harvard University, MA, USA. He can be reached at otto@interdevelopmentals.org.

This framework could be enriched by considering the work of other researchers who are doing applied research on reasoning and argumentation. For many of these researchers, the terms “argument” and “dialogue” are not opposed as they are in this article; “argument” for these researchers simply refers to how statements are organized within a dialogue, and arguments are organized differently within different types and subtypes of dialogue (e.g., Walton and Macagno, 2007). I’m reminded of Bernard Mayer’s phrase: “Genuine dialogue is not possible if we are not willing to engage in argumentation about our most important issues” (Mayer 2004). Here are some examples of this kind of research:

Pinar Seda Cetin (2014). Explicit argumentation instruction to facilitate conceptual understanding and argumentation skills. Research in Science & Technological Education, 32(1), 1–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2013.850071

Joshua Introne & Luca Iandoli (2014). Improving decision-making performance through argumentation: an argument-based decision support system to compute with evidence. Decision Support Systems, 64, 79–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2014.04.005

Mijung Kim, Robert Anthony, & David Blades (2014). Decision making through dialogue: a case study of analyzing preservice teachers’ argumentation on socioscientific issues. Research in Science Education. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9407-0

Nanon H. M. Labrie & Peter J. Schulz (2014). The effects of general practitioners’ use of argumentation to support their treatment advice: results of an experimental study using video-vignettes. Health Communication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.909276

Nanon H. M. Labrie & Peter J. Schulz (2014). Quantifying doctors’ argumentation in general practice consultation through content analysis: measurement development and preliminary results. Argumentation. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-014-9331-5

Edwin B. Van Lacum, Miriam A. Ossevoort, & Martin J. Goedhart (2014). A teaching strategy with a focus on argumentation to improve undergraduate students’ ability to read research articles. CBE Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 253–264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0110

Hee-Sun Lee, Ou Lydia Liu, Amy Pallant, Katrina Crotts Roohr, Sarah Pryputniewicz, & Zoë E. Buck (2014). Assessment of uncertainty-infused scientific argumentation. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(5), 581–605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.21147

Fabrizio Macagno, Elisabeth Mayweg-Paus, & Deanna Kuhn (2014). Argumentation theory in education studies: coding and improving students’ argumentative strategies. Topoi. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11245-014-9271-6

Fabrizio Macagno & Douglas N. Walton (2014). Emotive language in argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139565776

Antonio Bova & Francesco Arcidiacono (2013). Investigating children’s Why-questions: a study comparing argumentative and explanatory function. Discourse Studies, 15(6), 713–734. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461445613490013

Nancy L. Green (2013). Towards automated analysis of student arguments. In Lane, H. C., Yacef, K., Mostow, J., & Pavlik, P. (eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: 16th international conference, AIED 2013, Memphis, TN, USA, July 9–13, 2013: proceedings (pp. 591–594). Berlin: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39112-5_66

Michael H. G. Hoffmann (2013). Changing philosophy through technology: complexity and computer-supported collaborative argument mapping. Philosophy & Technology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13347-013-0143-6

Deanna Kuhn, Nicole Zillmer, Amanda Crowell, & Julia Zavala (2013). Developing norms of argumentation: metacognitive, epistemological, and social dimensions of developing argumentive competence. Cognition and Instruction, 31(4), 456–496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2013.830618

Fabrizio Macagno & Aikaterini Konstantinidou (2013). What students’ arguments can tell us: using argumentation schemes in science education. Argumentation, 27(3), 225–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-012-9284-5

Catarina Dutilh Novaes (2013). A dialogical account of deductive reasoning as a case study for how culture shapes cognition. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 13(5), 459–482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12342104

Douglas N. Walton & Nanning Zhang (2013). The epistemology of scientific evidence. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 21(2), 173–219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10506-012-9132-9

Arantza Aldea, René Bañares-Alcántara, & Simon Skrzypczak (2012). Managing information to support the decision making process. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, 11(3), 1250016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0219649212500165

Sarah Bigi & Sara Greco Morasso (2012). Keywords, frames and the reconstruction of material starting points in argumentation. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(10), 1135–1149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.04.011

Vasco Correia (2012). The ethics of argumentation. Informal Logic, 32(2), 222–241. http://phaenex.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/3530

Frans H. van Eemeren & Bart Garssen (eds.) (2012). Topical themes in argumentation theory: twenty exploratory studies. Dordrecht: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4041-9

Jos Hornikx & Ulrike Hahn (2012). Reasoning and argumentation: towards an integrated psychology of argumentation. Thinking & Reasoning, 18(3), 225–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2012.674715

D. Scott McCrickard (2012). Making claims: the claim as a knowledge design, capture, and sharing tool in HCI. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool. http://dx.doi.org/10.2200/S00423ED1V01Y201205HCI015

Sara Greco Morasso (2012). Contextual frames and their argumentative implications: a case study in media argumentation. Discourse Studies, 14(2), 197–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461445611433636

Florian Böttcher & Anke Meisert (2011). Argumentation in science education: a model-based framework. Science & Education, 20(2), 103–140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11191-010-9304-5

Harry M. Collins & Martin Weinel (2011). Transmuted expertise: how technical non-experts can assess experts and expertise. Argumentation, 25(3), 401–413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9217-8

Paul Culmsee & Kailash Awati (2013). The heretic’s guide to best practices: the reality of managing complex problems in organisations. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, Inc.

Theo L. Dawson & Zachary Stein (2011). We are all learning here: cycles of research and application in adult development. In Hoare, C. H. (ed.), The Oxford handbook of reciprocal adult development and learning (pp. 447–460). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199736300.013.0102

Sara Greco Morasso (2011). Argumentation in dispute mediation: a reasonable way to handle conflict. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub.

Hugo Mercier (2011). When experts argue: explaining the best and the worst of reasoning. Argumentation, 25(3), 313–327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9222-y

Paul Thagard (2011). Critical thinking and informal logic: neuropsychological perspectives. Informal Logic, 31(3), 152–170. http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/3398

Leema K. Berland & Katherine L. McNeill (2010). A learning progression for scientific argumentation: understanding student work and designing supportive instructional contexts. Science Education, 94(5), 765–793. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sce.20402

Michael J. Hogan & Zachary Stein (2010). Structuring thought: an examination of four methods. In Contreras, D. A. (ed.), Psychology of thinking (pp. 65–96). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Frans H. van Eemeren (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub.

Fabrizio Macagno & Douglas N. Walton (2010). What we hide in words: emotive words and persuasive definitions. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(7), 1997–2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.12.003

Gerald Nosich (2010). From argument and philosophy to critical thinking across the curriculum. Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, 25(3), 4–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.5840/inquiryctnews201025318

Douglas N. Walton & Fabrizio Macagno (2010). Wrenching from context: the manipulation of commitments. Argumentation, 24(3), 283–317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-009-9157-8

Douglas N. Walton (2010). Why fallacies appear to be better arguments than they are. Informal Logic, 30(2), 159–184. http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/2868

Kim A. Kastens, Shruti Agrawal, & Lynn S. Liben (2009). How students and field geologists reason in integrating spatial observations from outcrops to visualize a 3-D geological structure. International Journal of Science Education, 31(3), 365–393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500690802595797

Shirley Simon & Katherine Richardson (2009). Argumentation in school science: breaking the tradition of authoritative exposition through a pedagogy that promotes discussion and reasoning. Argumentation, 23(4), 469–493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-009-9164-9

Deanna Kuhn, Kalypso Iordanou, Maria Pease, & Clarice Wirkala (2008). Beyond control of variables: what needs to develop to achieve skilled scientific thinking?. Cognitive Development, 23(4), 435–451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2008.09.006

Alexandra Okada, Simon J. Buckingham Shum, & Tony Sherborne (eds.) (2008). Knowledge cartography: software tools and mapping techniques. New York: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84800-149-7

Keith E. Stanovich & Richard F. West (2008). On the relative independence of thinking biases and cognitive ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(4), 672–695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.672

Douglas N. Walton, Chris Reed, & Fabrizio Macagno (2008). Argumentation schemes. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Michael P. Weinstock (2008). Psychological research and the epistemological approach to argumentation. Informal Logic, 26(1), 103–120. http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/435

Katie Atkinson & Trevor Bench-Capon (2007). Practical reasoning as presumptive argumentation using action based alternating transition systems. Artificial Intelligence, 171(10–15), 855–874. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2007.04.009

Sibel Eruduran & Marilar Aleixandre (eds.) (2007). Argumentation in science education: perspectives from classroom-based research. New York: Springer.

Peter M. Kellett (2007). Conflict dialogue: working with layers of meaning for productive relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chris Reed, Douglas N. Walton, & Fabrizio Macagno (2007). Argument diagramming in logic, law and artificial intelligence. The Knowledge Engineering Review, 22(1), 87–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0269888907001051

Douglas N. Walton & Fabrizio Macagno (2007). Types of dialogue, dialectical relevance, and textual congruity. Anthropology & Philosophy, 8(1-2), 101–119. http://fabriziomacagno.altervista.org/uploads/2/6/7/7/26775238/typesdialogue-wama-anthropology8-2007.pdf

Douglas N. Walton (2007). Evaluating practical reasoning. Synthese, 157(2), 197–240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11229-007-9157-x

Mark Zachry & Charlotte Thralls (eds.) (2007). Communicative practices in workplaces and the professions: cultural perspectives on the regulation of discourse and organizations. Amityville, NY: Baywood Pub.

Mark Gerzon (2006). Leading through conflict: how successful leaders transform differences into opportunities. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Taeda Jovičić (2006). The effectiveness of argumentative strategies. Argumentation, 20(1), 29–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10503-005-1720-3

Marleen Kerkhof (2006). Making a difference: on the constraints of consensus building and the relevance of deliberation in stakeholder dialogues. Policy Sciences, 39(3), 279–299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11077-006-9024-5

Bernard S. Mayer (2004). Beyond neutrality: confronting the crisis in conflict resolution. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barbara Simpson, Bob Large, & Matthew O’Brien (2004). Bridging difference through dialogue: a constructivist perspective. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 17(1), 45–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720530490250697

Jerry Andriessen, Michael Baker, & Dan Suthers (eds.) (2003). Arguing to learn: confronting cognitions in computer-supported collaborative learning environments. Dordrecht; Boston: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0781-7

Paul Arthur Kirschner, Simon J. Buckingham Shum, & Chad S. Carr (eds.) (2003). Visualizing argumentation: software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making. London; New York: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0037-9

Douglas N. Walton (2003). Ethical argumentation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Nancy L. Stein & Elizabeth R. Albro (2001). The origins and nature of arguments: studies in conflict understanding, emotion, and negotiation. Discourse Processes, 32(2-3), 113–133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2001.9651594