Kazuma Matoba

1. Communication: The Issue

Kazuma Matoba

At the beginning of this third millennium AD, the world has achieved remarkable developments in global and instantaneous communication. Yet, in spite of these achievements, terrible human issues still persist due in large part to the darker side of cultural and individual diversity. In some way, these issues are always concerned with managing personal relationships and communication. Thus, all our individual and social problems share one common challenge: To effectively communicate and understand each other through words and nonverbals and to creatively explore and develop new (or redefine old) solutions to our problems; most of which we construct or co-construct ourselves.

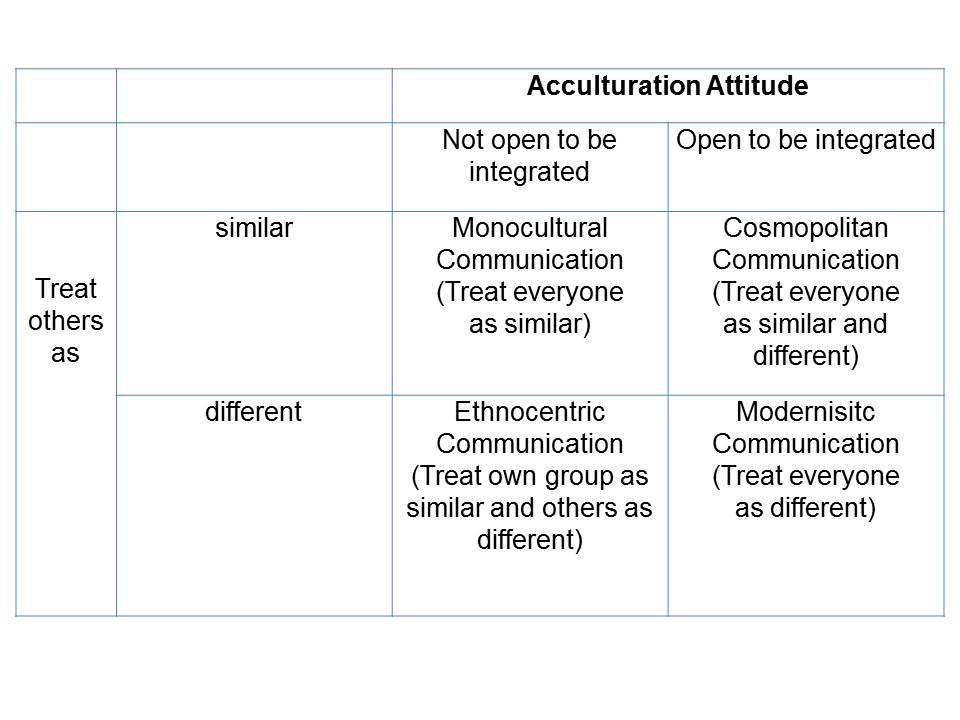

Pearce (1989) proposes a stage model of the evolution of communication in a multicultural society. According to this model, the form of communication in the social evolutionary process develops itself over four levels: (a) “monocultural communication”; (b) “ethnocentric communication”; (c) “modernistic communication”; (d) “cosmopolitan communication”. The human being should shift forward (and upward) by moving into the fourth phase: cosmopolitan communication. This kind of communication requires the development of a new level of awareness – global integral competence – which incorporates a more complete human and societal dimension of experience.

In this paper I will discuss about the paradigm shift of communication science by applying the Integral All Quadrants, All Levels (AQAL) map dealing with the following questions:

- How shall our communication in the future – cosmopolitan communication – be?

- How can communicative competence be developed in order to make “cosmopolitan communication” possible?

2. Evolutional Process of Communication

Pearce (1989) assumes that communication is the primary social process and that we create and recreate our realities, cultures, and identities through communication. He argues that “ways of being human” both grow out of and create their own “forms of communication” and “the relationship between forms of communication and ways of being human is similarly co-evolutionary” (1989:95). By “ways of being human” he means the evolutional process of social and cultural change through experiencing variously changing facts, values, relevancies, and affordances.

The communicators focus on the extent to which they treat each other as similar or different and whether their acculturation attitudes are open to being integrated. Treating others as similar means they consider these others to be part of their group and are judged by their own group’s standards. Treating them as different means realizing they are part of a different group and that they have different criteria for making judgments. Being open to developing a positive attitude and striving toward integration as a mutual and reciprocal form of acculturation is crucial in Pearce’s (1989) understanding of communication. Such an understanding implies furthermore being open to new and different stories, assumptions and ways of making sense of and creating meaning in the world. Conversely, those who are closed to developing such an attitude will not risk being influenced by others’ stories or assumptions. Pearce combines these points and makes them into criteria for a taxonomy of four forms of communication (monocultural, ethnocentric, modernistic and cosmopolitan).

Table 1: Forms of communication: Acculturation Attitudes and How Others are Treated (based on Grimes & Richard 2002:12)

Monocultural Communication

This communication posits that everyone is treated as similar because there is no distinction between one’s own group and other groups. It refers to a culture that has neither contact with nor information about groups outside its own. From the perspective that everyone is essentially similar or the same, “they would see disagreement as a lack of training or common sense” (Brown, 2005:50).

Ethnocentric Communication

Ethnocentric communication, according to Pearce, depicts those of one’s own group as similar and those of other groups as different. Ethnocentric communicators can interact with members of their own group without discomfort because their assumptions are not challenged. They are not open to being integrated because they believe strongly that their ways are best. They usually consider—or better, tacitly assume with little or no reflection—their group as superior and other groups inferior. Consequently, ethnocentric communicators naturally see differences as disagreements and therefore as a confirmation of their own stories of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. It further follows logically that disagreement initiates a win/lose contest that motivates them to protect their resources. In ethnocentric communication members of the in-group value and understand their own members and feel superior to members of other groups. They limit, ignore, devalue or dismiss crucial aspects of others, the fact of which can easily lead to dysfunctional affective conflict and estrangement.

Modernistic Communication

Modernistic communicators treat everyone as different. Brown (2005:51) states that “modernist communicators or modernists do acknowledge the value of differences as differences, and they would respond with enthusiasm, especially if the difference represented something ‘new’ to them; at least until its ‘newness’ wears off”. Disagreements would be seen either as problems to be solved or as challenges to find syntheses between opposing views. Grimes & Richard (2002:15) point out that modernistic communicators “do not feel strongly connected to any particular group”. Such a lack of connectedness often results in acculturation attitudes that are very open to change and to paths toward new forms of integration.

Cosmopolitan Communication

In this communication form everyone is treated as both similar and different. Here ‘everyone’ means both those who are considered a part of the inside group and those who are not. The cosmopolitan communicator recognizes others both as different and similar. Others are different in that they have their own worldviews and resources for dealing with the world. One can appreciate the differences and judge others by their own standards; “‘different’ is not assumed to mean inferior, and important group differences are not glossed over” (Grimes & Richard, 2002:16). Others are similar in that their focus and habits of attention provide similar functions for them as ours do for us.

Brown (2005:51) argues that disagreement through difference can be seen as positive because cosmopolitan communicators “would see disagreement as an opportunity for learning of different reality, and would interpret them as resources as long as they did not completely block coordination”. Being conscious of and ready to appreciate both aspects – the differences and similarities between and among individuals – makes communicators “more open to all perspectives and less likely to cling stubbornly to their own” (ibid. 19). As a consequence, this “both/and” appreciation can more easily facilitate genuine integration.

3. Cosmopolitan Communication as Design Communication

Cosmopolitan communication encompasses a most sophisticated taxonomy of communication forms, and may be regarded as sustainable and continuous process of “design communication.” Design communication is a form of communication that enables humans to transcend existing systems through communicative and emancipatory action (cf. Jenlink (2008:3)). Design communication is therefore based on the social constructionist process through which humans construct and reconstruct their social worlds through social interaction. In this light, communication is a process of making and doing. Our social worlds are expressed in conversations and these conversations, in turn, construct or reconstruct our social worlds. Each individual action and utterance is both a response to the acts that preceded it and a condition for the acts that will follow it. In a string of multiple actions by people engaged in conversation, a pattern of interaction emerges. With practice and repetition, a kind of logic or grammar can follow that guides the communicators in determining what to do and how to act.

Cosmopolitan communication as sustainable continuous process of design communication has four essential aspects: (1) persons-in-conversation, (2) energy-in-conversation, and (3) communication channel for information energy. After an explanation of these aspects a new definition of cosmopolitan communication is introduced.

(1) Persons-in-conversation

The fundamental assumption for the “Coordinated Management of Meaning” (CMM) theory by Pearce (1989) is that the quality of our personal lives and of our social worlds is directly related to the quality of communication in which we engage, because conversations among people are the basic material that forms the social universe. The theory of CMM starts with the premise that persons-in-conversation co-construct their own social realities, and are simultaneously shaped by the worlds they create. Communicators literally create their relationship whereas the mode and manner that persons-in-conversation adopt plays a considerable role in the social construction process.

(2) Energy-in-conversation

Social realities can be constructed not only through persons-in-conversation but also through energy-in-conversation. Energy is a construct that scholars in organizational theory use but seldom define. Quinn & Dutton (2005:43) report that energy-in-conversation is (1) a person’s energy level, which that person interprets automatically as a reflection of how desirable a situation is; (2) a person’s interpretation of a conversational partner’s energy from his or her expressive gestures; and (3) a feeling of being eager to act and capable of acting, which affects how much effort a person will invest into the conversation and into subsequent, related activities.

Linguistics and communication science are not much interested in “energy-in-conversation”, although the basic philosophical discussion has been done sufficiently in the speech act theory. This theory goes back to J. L. Austin´s development of performative utterances and his theory of locutionary (the direct performance of an utterance), illocutionary (the conventional consequences), and perlocutionary (psychological consequences) acts.Austin (1962) argues that a perlocutionary act is a speech act, as viewed at the level of its psychological consequences, such as persuading, convincing, scaring, enlightening, inspiring, or otherwise getting someone to do or realize something by an illocutionary act. For example, if someone shouts ‘fire’ and by that act causes people to exit a building that they believe to be on fire, they have performed the perlocutionary act of convincing other people to exit the building. Austin uses the notion of “illocutionary and perlocutionary forces,” which he did not define clearly. Some followers of Austin view illocutionary force as the property of an utterance to be made with the intention to perform a certain illocutionary act. According Bach & Harnish (1979), the addressee must have heard and understood that the speaker intends to make the addressee to do something in order for the utterance to have illocutionary force. If the speaker utters with an illocutionary force and the addressee is brought to perform something, then this performance has been done with a perlocutionary force. If we focus just on an aspect of meaning of certain utterances as illocutionary force, then it appears that the (intended) ‘force’ of the utterances is not quite obvious and sometimes we can not understand the real intended force by the speaker completely.

What is force? We should first make a distinction between meaning and information. Meaning is inherent in the intention of the source and information is the symbolic “form” of the meaning as it is conveyed by the carrier (energy). This energy may be not physical energy because information seems to bypass the usual space-time-energy mechanisms. Information theory shows that the entropy of a system decreases as the information increases. This suggests some kind of non-physical or “subtle energy” carrier, or, as Manzelli (2005) proposes, “information energy”. Anyway, we need to see a new aspect of illocutionary and perlocutionary force as a matter of energy that can bring out performances and construct social reality.

(3) Communication channel for information energy

David Bohm, in his book “Wholeness and the implicate order“ (1980), proposed a new model of reality in which “every element (…) contains enfolded within itself the totality of the universe”. His concept of totality includes both matter and mind and explains an enfoldment of thought. Our individual consciousness is an enfoldment of many thoughts and emotions over time, creating implicate patterns or relationships. Language is an enfoldment of symbols and meanings that create an implicate order. As individuals engage in communicative interactions, the meaning implicate in language is unfolded in the communicative field between them through the discursive interactions. Jenlink (2008:15) argues that “as meaning unfolds through communication, the implicate nature of meaning is made explicate, creating opportunity for the participants to generate common meaning through sharing.“ Such sharing, as a multi-faceted process, looks well beyond conventional ideas of conversational exchange. “Dialogue“ proposed by Bohm (1996) as sharing explores the manner in which thought is generated and sustained on a collective level, if “we can all suspend carrying out our impulses, suspend our assumptions, and look at them all“ (Bohm, 1980:33). “Suspension“, which is for Bohm a mode of awareness critical to the development of dialogue, means that a participant for the moment neither accepts nor rejects her/his beliefs, opinions and emotions as reality. It means rather that she/he observes that she/he is experiencing beliefs, opinions and emotions and suspends judgment on them in order to examine the ways they shape her/his perspective and ability to experience and respond to others in dialogue.

For the successful suspension, a receiver should catch the information energy from a sender and resonate with it. The information enfolded in the sender´s messages conveyed by information energy can be unfolded through communicative relationships between the sender and receiver, but the receiver can not receive all information because not all communication channels are sufficiently developed. The visual and auditory communication channels as main communicative sensation are well developed for catching visual and auditory information, but psychological and neural physiological proprioception is less developed as a sensational channel for receiving information energy.

In physiology, the term proprioception refers to the capacity of the body to have self-awareness of its own movements. Bohm introduced the term “proprioception of thought” to refer to the possibility for thought to become aware of its own movements as well through direct perception. The proprioceptive communication channel refers to information received through body phenomena such as feelings, pain, pressure, tension, and temperature (Dennehy, 1989).

The other two communication channels Mindell (1985) mentions are the “relationship channel” and the “world channel”. The relationship channel includes information received through relationship or lack of relationship. The world channel includes perception from the outside world such as job, money, family, world events, and the universe. Mindell (1985) associates the visual and the auditory channels with the mind. The proprioceptive channels he associates with the body, and the relationship and world channels are associated with the universe or the environment.

(4) Redefinition: cosmopolitan communication

In the time of globalization in which modernistic communication has been promoted and appreciated, communicators using this mode may not be able to communicate well with all of the different members in their societies. This lack of ability can fail to maximize the positive potential of differences and therefore also fail to create something new from implicit tensions involved. The next evolutionary stage of communication, cosmopolitan communication, should contribute to a long-term process of unifying diversity during which all differences are recognized, acknowledged and appreciated as inevitable parts of the whole. Matoba (2011:163) argues that “a diverse individual feels confident that her/his own cognitive diversity can mature only if it is linked with the cognitive diversity of the other”. The process of jointly constructing meaning is nourished by the acceptance of, in Gergen‘s words, “relational responsibility” (1999:156).

Considering all of the above features from (1) to (3), cosmopolitan communication can be redefined as follows:

“Cosmopolitan communication is a form of persons-in-conversation and energy-in-conversation which can create a social reality with unified diversity and relational responsibility by resonating and synchronizing with information energy between communicators through all communication channels.”

4. Global Integral Competence

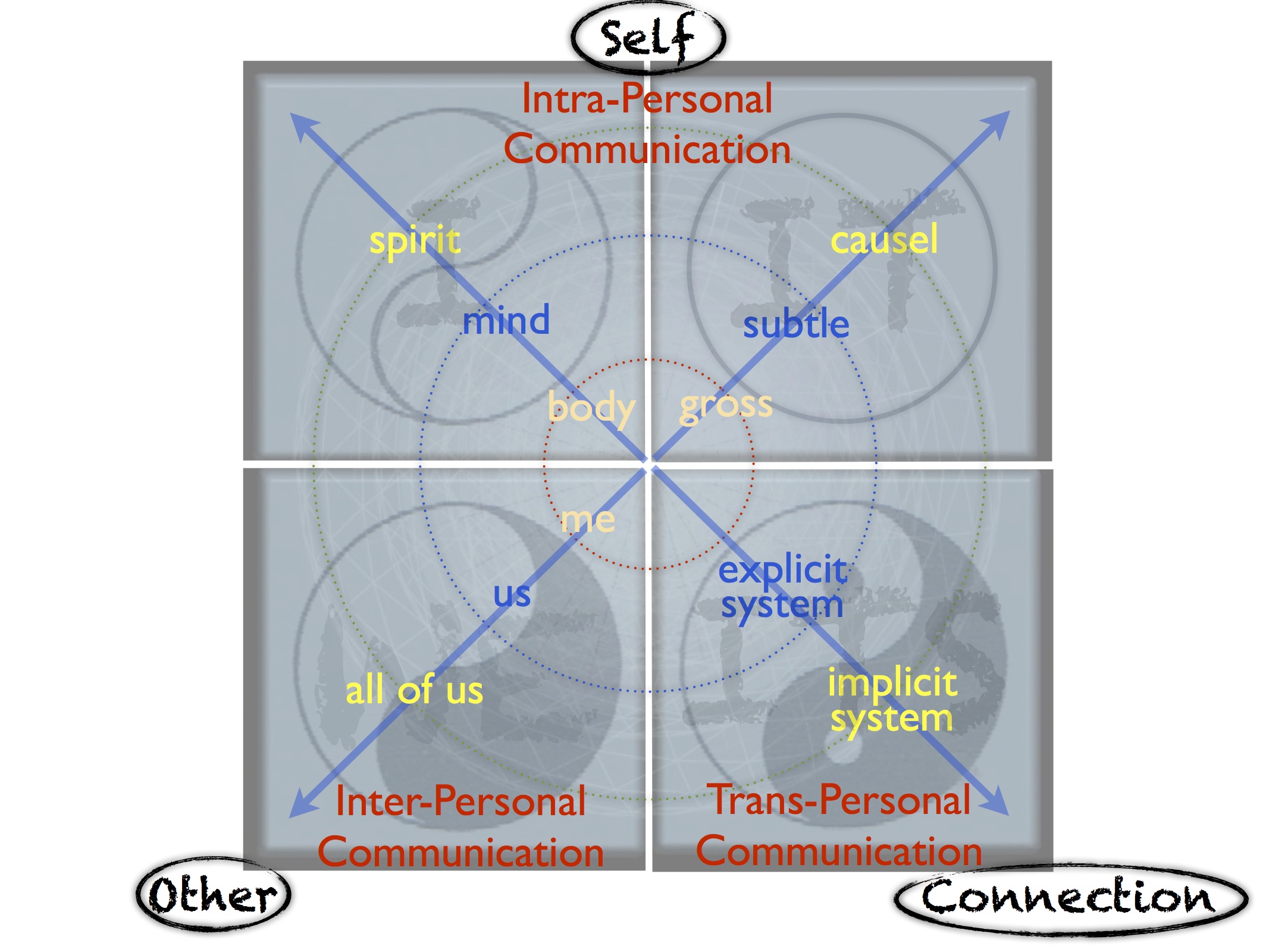

To promote “cosmopolitan communication” as simply another form of intercultural competence is not sufficient because this concept traditionally considers just a small, predominantly cognitive subset of the whole spectrum of human life, social development, and international exchange. We must instead develop a new level of competence that covers all dimensions of human communication: intra-, inter- and transpersonal communication. Only then will we have communication that can truly be called “cosmopolitan.”

4.1. AQAL map and three dimensions of communication

The three types of communication just described – intra-, inter- and transpersonal communication – can be redefined and described based upon the AQAL map.

- Intra-personal communication: communication with self

— Communication with body/brain

The body is constantly sending out signals that can tell us a great deal about ourselves if we learn and understand them. Although much is yet to be learned about how we can control bodily functions, biofeedback is being used to help people decrease tension and anxiety, to increase or decrease particular brain waves, to cure migraine headaches and other bodily ills.

— Communication with mind/soul

Intra-personal communication limits itself to communication within the individual. It is communication that takes place within the individual when she/he is communicating with others, or simply when she/he is alone and thinking to her-/himself. When a person says to her-/himself, “way to go,” she/he is engaging in intra-personal communication. The practice of intra-personal communication is critical to helping us develop not only our sense of self but also help us identify how to communicate with others. Our value of ourselves determines how we communicate with others so it is important to assess our self-concept.

2. Inter-personal communication: communication with others

Communication exists on a continuum from impersonal to interpersonal. Much of our communication involves no personal interaction. We acknowledge each other as people, but we don’t engage in intimate talk. Buber (1958) says that this continuum exists at levels: I-It, I-you, and I-Thou.

— I-It communication: in this relationship we treat other very impersonally, almost as objects. We simply interact because we need to but do not see individuals as human beings.

— I-You Communication: This is the second level according to Buber. People acknowledge one another as more than objects, but they don’t fully engage each other as unique individuals. Casual friends, work associates, and distant family members typically engage in I-You communication.

— I-Thou Communication: Buber regarded this as the highest form of human dialogue because each person affirms the other as cherished and unique. When we interact on an I-Thou level, we meet others in their wholeness and individuality instead of dealing with them as an entity. Buber believes it is at this level we truly hold human relationships. At this level we are genuine about ourselves.

3. Trans-personal communication: communication with systems

The ability of a person to establish and maintain contact with her/his inner core is called trans-personal communication (Weinhold & Elliott, 1979:114). At our core there is an awareness of our unity with all other people and a profound sense of connectedness with everything in our universe. Transpersonal communication is possible by being aware of explicate and implicate systems around us.

— Communication with explicate systems

We are living in many systems like groups/families, nation/state, societies/organizations, and ecosystems. These systems are social “holons”, containing both a whole and a part of a larger system. This social holon does not possess a dominant monad; it possesses only a definable “we-ness”, as it is a collective made up of individual holons. In addition, rather than possessing discrete agency, a social holon possesses what is defined as nexus agency. By being aware of explicate systems we can know about how to liberate and unfold our potential in the system.

— Communication with implicate systems

We are living also in implicate systems that are invisible and cannot be recognized by our five senses. This implicate system is ruled by an “implicate order” as proposed and defined by David Bohm. According to Bohm’s theory, implicate and explicate orders are characterized by their spatial and temporal characteristics. In the enfolded [or implicate] order, space and time are no longer the dominant factors determining the relationships of dependence or independence of different elements. Rather, an entirely different sort of basic connection of elements is possible, from which our ordinary notions of space and time, along with those of separately existent material particles, are abstracted as forms derived from the deeper order. These ordinary notions in fact appear in what is called the “explicate” or “unfolded” order, which is a special and distinguished form contained within the general totality of all the implicate orders (Bohm 1980, p. xv).

Effective intra-personal communication enables us to establish contact with and utilize our inner thoughts, feelings, experiences and energies for developing of energy-in-conversation. Effective inter-personal communication helps build an atmosphere of trust and connectedness with other people for developing of persons-in-conversation. Trans-personal communication rests upon the foundation of effective intra-personal and inter-personal communication to bring us to an expanded contact with the full range of human experiences in ourself and others (Weinhold & Elliott, 1979). The integration of these three types of communication involves the use of skills and understanding to help us become aware of our essential unity and connectedness with all life energy for creating of social reality with unified diversity and relational responsibility.

This integration of these three dimensions of communication needs a mature competence that I call “global integral competence (GIC)”. GIC is the set of skills, knowledge, attitudes, consciousness, and coherence with which a growing group of people engages the world. GIC tries to understand and integrate all perspectives that emerged in human history, and value the systems that we have created over the ages to cope with the challenges of our species.

Figure 1. Intra-, inter- and trans-personal communication in AQAL map

4.2. Training Methods

Through the theoretical combination of the three types of communication discussed earlier with integral theory, we can create a more clear approach for cosmopolitan communication. We can draw upon resources from all four quadrants to coordinate action (coordination) and manage meaning (coherence) through intra- and inter-personal communication, and also be connected to each other by sensing and accepting implicate systems around us through trans-personal communication. Training methods for developing global integral competence for cosmopolitan communication should consider all aspects of communication: intra-, inter- and transpersonal communication. They should also be based upon universal values and worldview of human realities beyond cultural diversity, not simply rooted in a particular culture of origin, as are many of today’s “euro-centric” methods. “Transparent communication” and “transformative dialogue” are two examples of such approaches.

Transparent Communication

Transparent Communication developed by Thomas Hübl (2009a, 2009b, 2011) enables us to “access a more extensive level of information in our lives” and to “move beyond the interpretation (understanding) of humans as objects in the physical world and thus experience humans from within” (2009b). This method helps us to “acknowledge the true cause of many conflicts, looking beyond the symptoms to the root of the problem” (ibid). The aim of this method is to establish a new WE-culture by “achieving a high degree of interpersonal clarity, supporting our authentic expression, not to mention an expansion of the collective intelligence”.

Transparent communication consists of various training approaches to develop our intra-, inter- and trans-personal communication competence for “higher and more transcendent layers of consciousness” (Hübl, 2011:8). The following are representative training approaches:

- Feedback: a training to perceive and share everything that comes up within us in an encounter with other people.

- Body awareness: a training to get to a deeper sensation of body.

- Looking into different parts of life: a training to perceive information about the life of the person in her/his energetic field.

- The screen of clairvoyance: a training to strengthen “inner screen” reflecting messages and visions which originate in layers of our consciousness located below the surface of regular mind consciousness.

- Reading: a psychic training to find answers for all those who are, at present, not yet able to see their lives clearly.

Transformative Dialogue

Matoba (2002, 2011), applying the ideas of Bohm, reports the dialogue process of transformative dialogue works best in the beginning with twenty to forty people seated facing one another in a circle. At least one or two experienced facilitators are essential. The aim of the transformative dialogue is to slow down the communication, to develop mutual trust and to build up the collective field (container). Each participant who wants to respond to what the last speakers have said takes the stone from the center of the circle and begins to speak (or remain silent). When the participant with the stone is finished, she/he puts the stone back in the middle. In this way the transformative dialogue goes on for about 90 or 120 minutes without an agenda or any special subject for discussion. Sometimes a long silence occurs. Matoba (2011:159) recognizes a basic developmental sequence that the transformative dialogue follows: (I) Stage 1: First culture in ethnocentric communication focusing on the self (I-It), (II) Stage 2: Second culture in modernistic communication focusing on the other (I-You), (III) Stage 3: Third culture in cosmopolitan communication focusing on connection (I-Thou).

5. Summary and suggestions for future´s research

Karl Popper proposed the rebuilding of the Tower of Babel in his socio-political project, which is also the title of one of his major works, “The Open Society and its Enemies.”

“It is often asserted that discussion is only possible between people who have a common language and accept common basic assumptions. I think that this is a mistake. All that is needed is a readiness to learn from one‘s partner in the discussion, which includes a genuine wish to understand what he intends to say. If this readiness is there, the discussion will be the more fruitful the more the partners‘ backgrounds differ. Thus the value of a discussion depends largely upon the variety of the competing views. Had there been no Tower of Babel, we should invent it.”

Popper (1963, 1994:158)

Borrowing on Popper‘s ideas, this paper focuses on the building of a new, (and for God‘s sake, less grandiose) Tower of Babel, so designed that cosmopolitan communication can be attained through global integral competence. Cosmopolitan communication is more about a human project than a Holy mission for rebuilding the Tower; it is about a very human, imperfect construction of design communication. The project needs a conceptual approach for establishing a foundation of the building and a precise blueprint which provides a practical guide for the construction work. This approach conforms to the integral theory of Ken Wilber and the theoretical assumptions of social construction of Barnet Pearce, who formulates his own dialogical perspective as a means of coordinating our behavior to build more adequate interpersonal relationships. This approach can be implemented by a blueprint which consists of three areas – persons-in-conversation, energy-in-conversation, and communication channel for information energy.

The first step of this project was set in a forum of the Society for Intercultural Education, Training and Research (SIETAR) titled “Global Integral Competence: mind, culture, brain and system” held in September 2012 in Berlin. The organizer of this forum declared that a new platform for research and education of cosmopolitan communication would be offered continuously until 2050. The second step of this project is an intensive discussion about a possible application of cosmopolitan communication in the research and education field of medical communication. There, medical staffs are dialogue facilitators for clients in their self-regulation and should be in resonance with clients so that they can recognize new communicative constructed situations as coherent. In this dialogical situation, a “non-verbal transpersonal holistic psychosomatic communication” (cf. Bedričić et. al, 2011) takes place and new values are created. The result of the research with this hypothesis will be presented in February/March 2014 in Bonn/Germany.

References

Austin, J. (1962): How To Do Things with Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bach, K. & R. M. Harnish (1979): Linguistic Communication and Speech Acts, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Bedričić, Stokić, Milosavljević, Milovanović, Ostojić, Raković, Sovilj, and Maksimović (2011): Psycho-physiological correlates of non-verbal transpersonal holistic psychosomatic communication. Verbal Communication Quality Interdisciplinary Research I, S. Jovičić, M. Subotić (eds), LAAC & IEPSP, Belgrade.

Bohm, D. (1980): Wholeness and implicate order. London: Routledge.

––––––(1996): On dialogue. London, New York: Routledge.

Brown, M. (2005): Corporate integrity: Rethinking organizational ethics and

leadership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buber, M. (1958): I and thou. New York: Scribner.

Dennehy, V. (1989): Process Oriented Psychotherapy. Dissertation.

Gelber, K. (2002): Speaking Back: The Free Speech Versus Hate Speech Debate. John Benjamins, 2002

Gergen, K. (1999): “An invitation to relational responsibility“. In. S. McNamee, K. Gergen (eds.), Relational responsibility. ThousandOaks: Sage.

Grimes, D.S. & Richard, O. (2002): “Could communication form impact

organizations’ experience with diversity?” The Journal of Business

Communication, 40(1), pp. 7-27.

Hübl, T. (2009a): Sharing the Presence: Wie Präsenz dein Leben transformiert. Bielefeld: Kamphausen Verlag.

––––––(2009b): http://www.thomashuebl.com/en/approach-methods/transparent-

communication.html

––––––(2011): Transparence. Berlin: Academy of Inner Science.

Jenlink, P. (2008): Design conversation. In. P. Jenlink & B. Banathy (eds.). Dialogue

as a collective means of design conversation. New York: Springer.

Manzelli, P. (2005): Information, knowledge, evolution. http://www.edscuola.it

/archivio/lre/science_of_information_energy.htm

Matoba, K. (2002): ―Dialogue process as communication training for multicultural

organizations‖. In. S. Bohnet-Joschko & D. Schiereck (eds.),Socially responsible

management: Impulses for good governance in a changing world. Marburg:

Metropolis.

–––––(2011): Transformative dialogue for third culture building: Integrated constructionist approach for managing diversity. Opladen: Budrich UniPress.

Mindell, A. (1985): River’s way: the process science of the dreambody: information

and channels in dream and bodywork, psychology and physics, Taoism and

alchemy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Pearce, W.B. (1989): Communication and the human condition. Carbondale,

Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Popper, K. (1963, 1994): Public Opinion and Liberal Principles. In. In search of a

better world. London: Routledge.

Quinn, Ryan & Jane E. Dutton (2005): Coordination as energy-in-conversation.

Academy of Management Review. Vol 30. No. 1. P. 36-57.

Weinhold, B. & Elliot, L.C. (1979): “Transpersonal communication: How to establish

contact with yourself and others. London: Prentice-Hall.

Wilber, Ken (2006): Integral spirituality. Boston, London: Integral Books.

About the Author

Kazuma Matoba, PhD, teaches and researches at University of Federal Armed Force in Munich/Germany. His research focus is evolution of communication, global integral competence and diversity management. He studied linguistics at Sophia University in Tokyo and got PhD of communication science from University Duisburg in Germany. He is a founder and director of Institute for Global Integral Competence (www.ifgic.org) and authors of many publications.

https://www.neuroquantology.com/index.php/journal/article/view/1267

http://integralleadershipreview.com/9013-the-aqal-cube-for-dummies/

Great article Kazuma. Hope you are able to still get this message. My above two links corroborate your ideas, and I regret I had not seen your work before they were published.