Third in a Three Part Series

Edward J Kelly

Abstract

Edward J. Kelly

This is the third in a series of articles for the Integral Leadership Review in which I have attempted to explain my research on adult development. As readers of the previous two articles will note, I have explored this topic in depth by looking at Warren Buffett’s development and how it impacted his success, particularly as a leader. Following an Action Inquiry design (Torbert et al, 2004), the first article reported on the third-person findings from the research, ‘what was the research about, what methods of inquiry were used and what were the results’? In the second article I considered, ‘what are the second-person implications of the research for the field of leadership studies’? In this final article, I consider, from a first-person perspective, ‘what impact did the research have on me’? The answer is that it focussed attention on my own development – how had I changed and developed over my adult life? As I had created a Developmental Biography of Buffett’s adult life, I now created a Developmental Autobiography of my own, which I report on here.

An early view of adult development

At 15 I set my heart upon learning

At 30, I had planted my feet firm upon the ground.

At 40, I no longer suffered from perplexities.

At 50, I knew what were the biddings of heaven.

At 60, I heard them with docile ears.

At 70, I could follow the dictates of my own heart; for what I desired no longer overstepped the boundaries of right”.From Confucius in The Analects

Introduction

The topic of adult development goes to the heart of an unresolved question in leadership studies, ‘are leaders born or made’? This in turn is reflected in an ongoing discussion in philosophy and psychology about whether we have a core identity that is sitting there waiting to be discovered or whether our true selves are constructed over time. Adult developmental theory favours the evolutionary view, it sees that as we grow and develop, new selves become available to us. In Buffett’s case it is likely to be a mixture of both. He seems to have been “hard-wired” for success as an investor in that his logical mathematical intelligence and rational temperament adapted him well for a life as an investor, but not hard-wired for success as a leader; rather he became a successful leader both through opportunity and circumstances and through his own intentional acts of learning and development. It is this aspect of development that is relevant to leadership studies, that when it comes to leadership development, the development must come first.

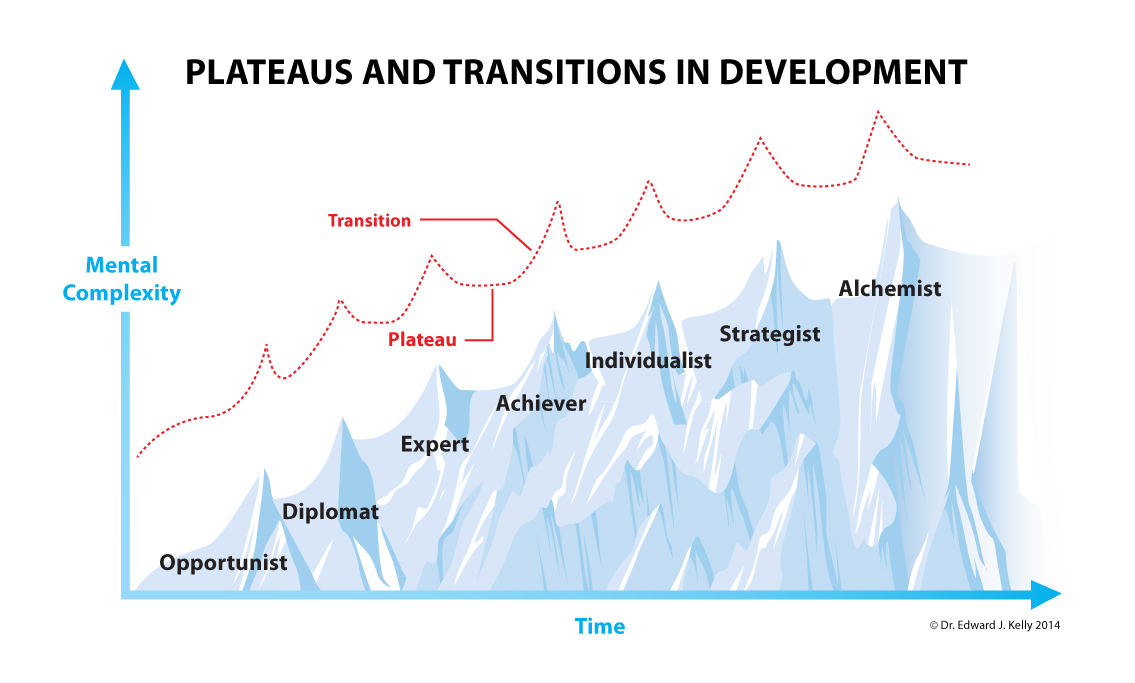

Figure 1. Plateaus & transitions in development

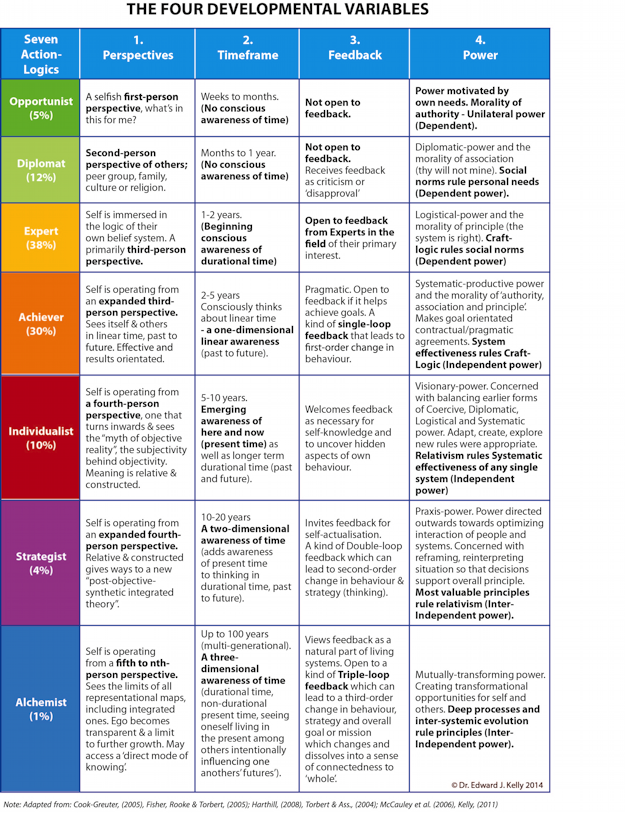

Formally, a Developmental Autobiography is a self-assessed exploration of the plateaus and transitions in our development as adults. As seen through the action-logics in developmental theory, a plateau refers to a stable period in which our underlying meaning-making remains the same. A transition refers to a relatively unstable period in which our underlying meaning-making changes. We identify the ‘plateaus’ by exploring our capacity for ‘perspective taking, awareness of time, openness to feedback and use of power’ (the four developmental variables – see appendix 1) and we explore the ‘transitions’ by examining the mix of internal and external factors that are present in our transformation from one action-logic stage to the next. Are we pulled along by circumstances outside of us or pushed along by forces within, or some mix of both? This formal psychological approach is the one I take in this article.

Informally though, a Developmental Autobiography is also a look at the many adult lives of Edward Kelly; Ed the undergrad, Ed the apprentice solicitor, Ed the adventurer and entrepreneur, Ed the doctoral student, Ed the consultant, Ed the facilitator. Just how different was I during these different periods in my life? For instance, when I look back on my late twenties and see myself in the documentary of The Great London to Sydney Taxi Ride in 1988, I cringe. Was I really like that? What also of the various roles (selves) that I display to other people? To what extent do I, as TS Eliot said, put on a face on to meet the faces of the people I meet? I am also a husband, a father to four kids, a sibling to three brothers and two sisters and a member of various communities, on-line and off-line. How do I seem to these people?

Also, these are my adult years, what of my formative years growing up? To what extent does my adult development reflect my continuing to act out some early unconscious needs? Adult development theory doesn’t talk about the importance of our nature, what we are born with. Nor does it speak of our nurture, what we are born into? Reflecting on my life conditions, just how fortunate have I been? How have I been lifted up or held back by others; my family, my culture, my education, my society, my time in history? James Joyce says in A Portrait of an Artist of a Young Man that, “When a man is born…there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”

So it’s complex. There is a lot going when you start to think about development. ‘Who am I anyway’ you might well ask? What baggage am I carrying? Where did I pick it up? Why is it so heavy? I recall someone telling me that Robert Frost had said that in order to adapt to life, particularly in the early years, we cut off parts of our psyche that we throw into a big black bag which we carry on our backs. By the age of 40 or 50 the bags start getting stuck in the lift. At some point we need to turn around and look at what’s in the bag and ask, how appropriate is it to the journey ahead?

Given the enormity of the task, A Developmental Autobiography is just a start, a start of the process of emptying the big black bag. For those up for the adventure, you are likely to see just how important your nature and nurture continues to be in your life. Equally though you will also see how much you have changed and developed in your adult years and how the boundaries of your early conditioning have frayed. You are not a slave to your pre-dispositions nor are you completely dependent on your circumstances. You also have an agency, will or character that allows you stand back and act consciously in the moment. And as Stephen Pinker says, “and if my genes don’t like it they can go jump in the lake”.

What the theory says

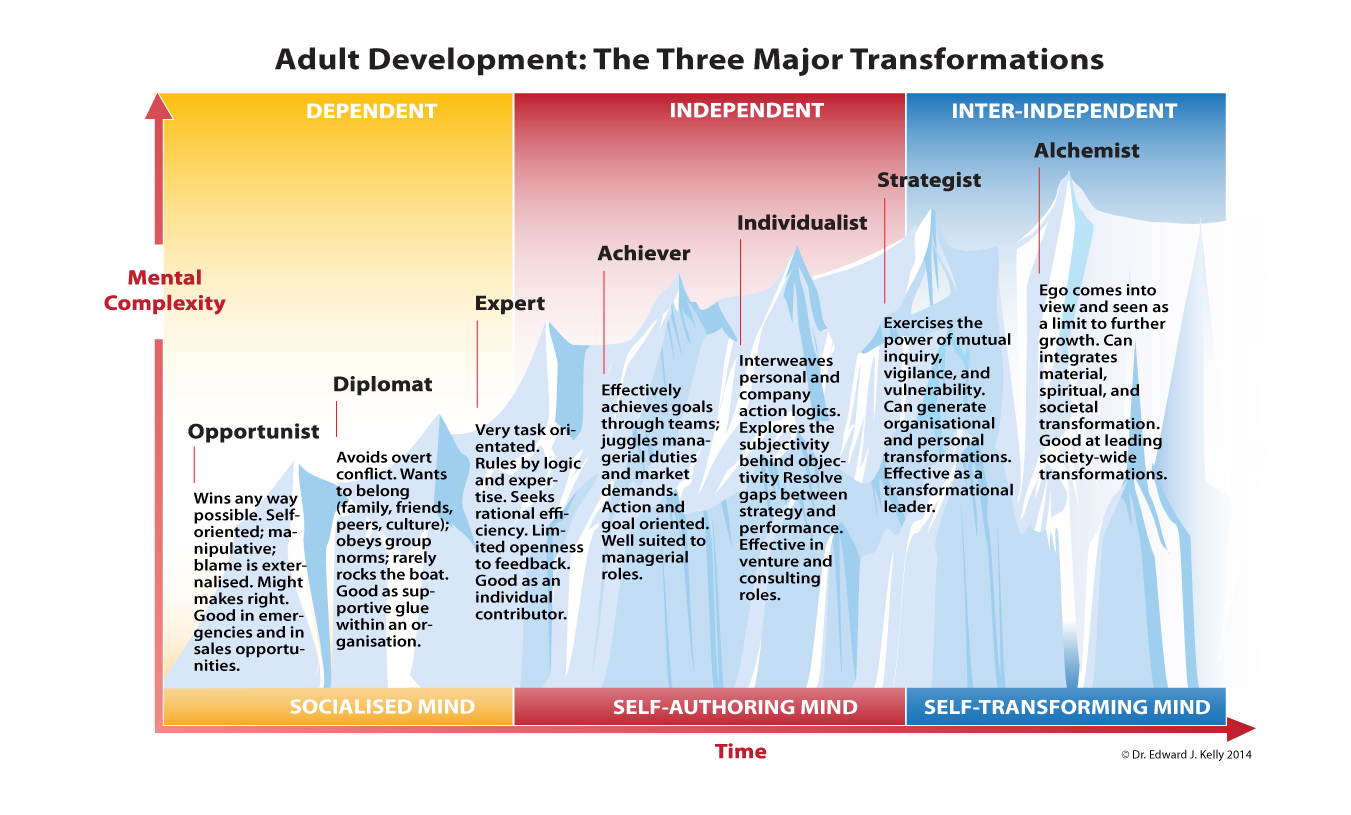

Adult developmental theory is a theory of the sequential order of development of the self. It studies how our character, ego, consciousness or awareness develops as adults. Depending on the researcher, this is described as occurring in waves, orders, phases, levels or stages of growth. In Torbert’s theory (Torbert et al., 2004), which I primarily use, the stages of development are known as action-logics of which there are seven, the Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert, Achiever, Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist. (Please see articles 1 and 2 for a more detailed description and references to each of the stages of development). According to the theory, most adults enter adulthood with a meaning-making at the Diplomat or Expert action-logic and this is where my Developmental Autobiography begins. From there I track my development through three major transformations; from a Dependent phase (which aligns with the Opportunist and Diplomat), to an Independent phase (which aligns with the Expert, Achiever and Individualist) to an Inter-Independent phase (which aligns with the Strategist and Alchemist). These major developments in the self are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Action-logic stages of adult development

I completed my Developmental Autobiography in three parts as follows;

Firstly, I read over the descriptions of each of the stages in adult developmental theory (see figure 2 and table 2) and reflected on which ones resonated most with different periods in my adult life. At least theoretically, the earlier action-logics (Opportunist and Diplomat) are more often seen in our young adult years, the middle action-logics (Expert, Achiever and Individualist) in our early to mid adult years and the later action-logics (Strategist and Alchemist) in our mid to later years, and this was the case for me.

Secondly, I took incidents from each of the main periods in my life and looked at them in some detail. Applying the four developmental variables (see appendix 1), ‘perspectives, timeframe, feedback and use of power’, I looked at what was my underlying meaning-making or awareness in my actions at the time? What range of ‘perspectives’ was I aware of? What ‘timeframe’ was I aware of? How open was I to ‘feedback’ from myself, others and the world around me? And, how did I use my ‘power’ and influence in action? From this inquiry I established the ‘developmental depth’ in my actions which I then matched to one or more of the action-logic stages of development in the theory. This is possible as the four variables are experienced differently at each action-logic stage of development.

Thirdly, then having established the plateau or action-logic stage that I was operating from at the time, I reflected on what was going on as I transitioned from one action-logic stage to the next. What mix of internal and external push and pull factors were present in my transformation? What happened to make me change? Did some external event trigger that change or was it preceded by some internal change in my meaning-making, or was it some mix of both?

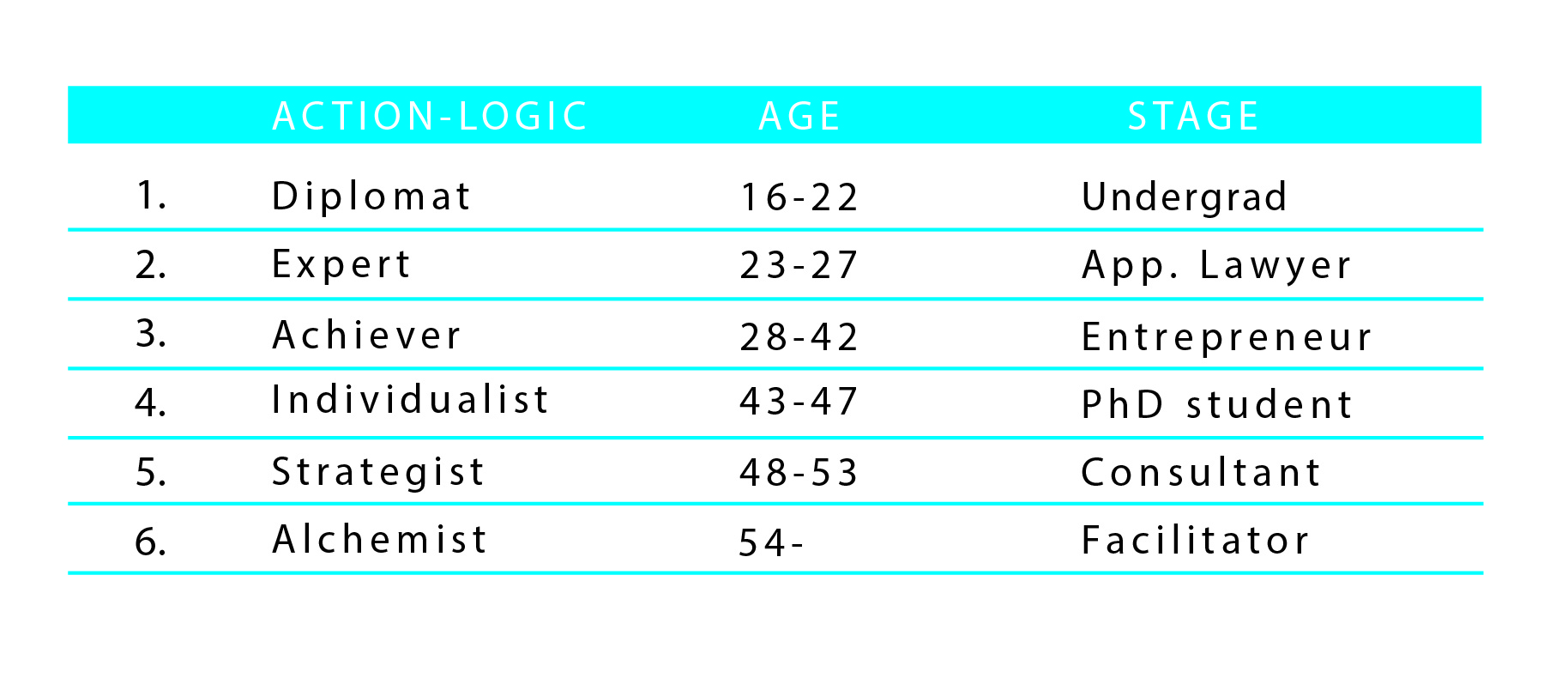

A Developmental Autobiography of Edward Kelly

In my case, my Developmental Autobiography starts at the Diplomat action-logic stage, which matches with my meaning-making as an undergraduate. That follows with the Expert action-logic, which matches with me training to become a lawyer,and so on. The Achiever action-logicwith my time as an entrepreneur, the Individualist action-logicwith my commencing a PhD in my early forties, the Strategist action-logic with starting a consulting practice and more recently the Alchemist action-logic with a more fluid appreciation of all theories and methods reflected in my developing role as a facilitator. The labels here are used as entry points to inquiry; the territory is not fixed. I can’t for instance remember exactly when my centre-of-gravity shifted from Expert to Achiever and yet I am confident that it did occur.

Table 1. My Developmental Autobiography

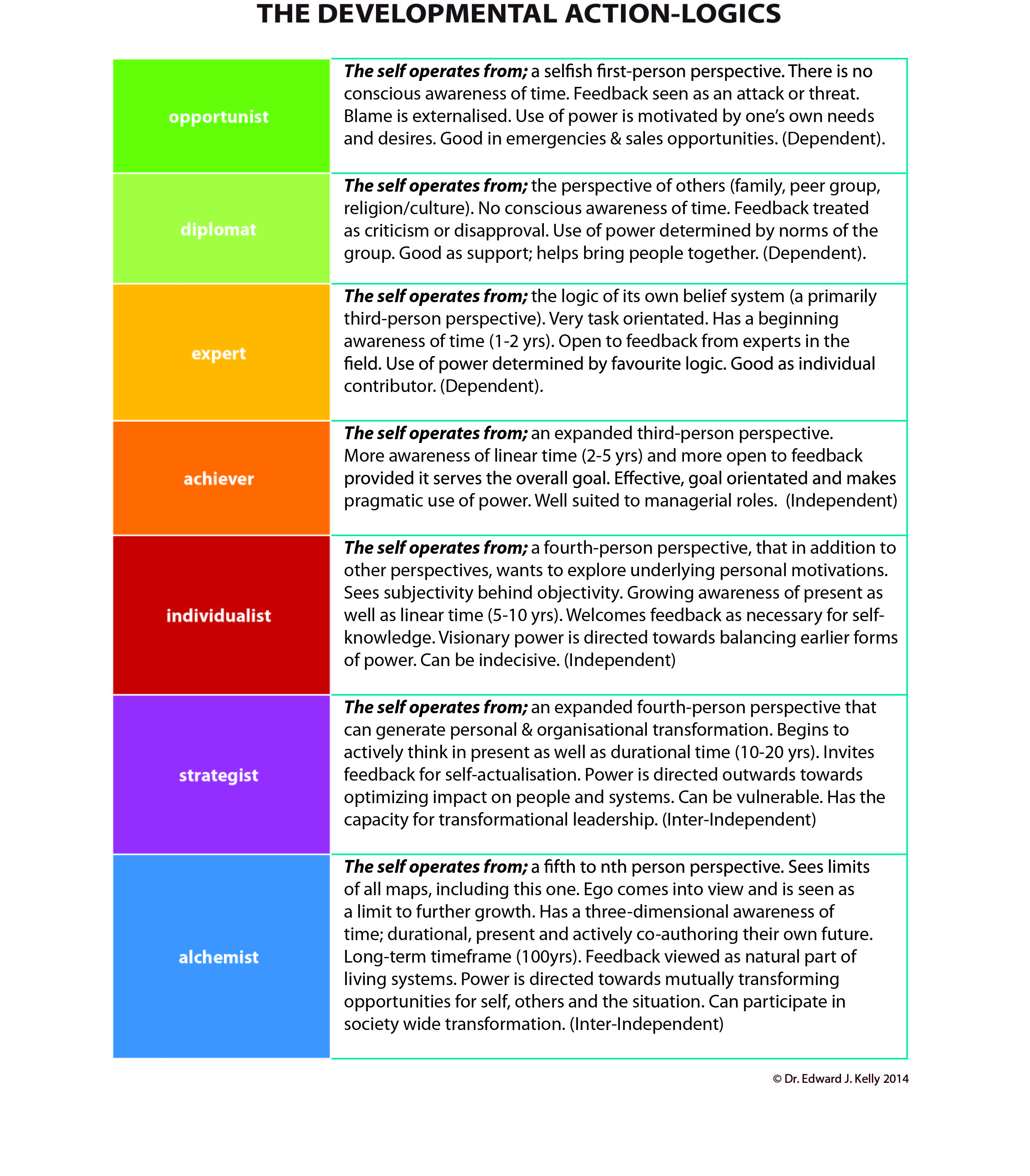

Is my underlying action-logic the only thing motivating my actions? No. It is merely to point out that it is an influential factor and one that is often ignored in the face of more dominant factors such as personality and circumstances. My level of awareness stands in between my personality and my circumstances. It is acts as my internal control system that makes sense of my experiences, both internal and external. It plays a role in where my attention is directed to and what actions I take. And it is not just a cognitive function either. Descartes famously said that, “I think therefore I am” to which Sartre later added, “if you think therefore you are, who is doing the observing of you doing the thinking”? There is something else that emerges through our development that allows us see ourselves in action. What are we then, the seer or the seen or some mix of both? The Jesuit Philosopher Bernard Lonergan said that if you want to know what is known, you have to know how the knower knows. Developmental theory looks at that through stages of growth in the self as follows.

Table 2. The Developmental Action-Logics

1. The Diplomat Action-Logic

According to the theory, at the Diplomat action-logic the self’s centre-of-gravity is centred on others; peer group, family, culture or society (a primarily second-person perspective). In the process, the self suppresses its own desires and conflicts in favour of the group. It seeks membership and belonging at all costs. There is little conscious awareness of time; little or no openness to feedback, and feedback that is given is seen as a criticism or disapproval. Diplomatic power is based on the morality of association, thy will not mine. Social norms take precedence over personal needs.

Plateau

I associate my meaning-making at The Diplomat Action-Logic with my late teens and years as an undergraduate. My nickname at the time was “Henry” (after Henry Kissinger) – I was the one called in to resolve disputes. I was so good at it that I wondered later should I follow a career in Diplomacy. At the time I was very attached to my peer group at College and felt very alone when it all came to an end. (You might say that there is nothing unusual about that, and that is the point – all adults who transform from a Diplomat to Expert action-logic experience this sense of loss to one degree or another). At the same time I also felt a need to move onto the next stage in life; to get a job and to provide for myself. I was resisting though, in part because I was not ready for the responsibility that such a step would entail.

As I reflect on my underlying meaning-making at the time, and consider the four developmental depth questions, I would say that my perspective taking was very much determined by others. I would have done anything to remain part of the group. Taken by such concerns I had no particular awareness of time. My openness to feedback was also limited to what others wanted of me. Being so adaptable and amenable, I had no real sense of who ‘my-self’ was. I was bobbing along in someone else’s stream.

Transition

Internal process 1 – the push that comes from a negative association with the current stage. On leaving College, I had a real existential crisis and not just a temporary loss of faith, but a real sense of my world collapsing. I stopped functioning. I was lonely, confused and frightened and could not understand what was going on.

Internal process 2 – the pull that comes from a positive association with the next stage. There was also a pull to move on and become ‘something’ or ‘somebody’ in the world, to have an identity to attach to, a skill, a title or a label, such as, “Ed the solicitor” or “Ed the entrepreneur”. Looking for help, I found a mentor to help me.

External process 1 – a change in role or responsibility that requires a wider range of capabilities. My internal disorder pushed me to moving location, in this case, from Ireland to Australia. When I got there I was forced to find somewhere to live, to get a job to support myself and to make new friends in order to have a social life.

External process 2 – a change in the external system that the individual is subject to. This occurred through a new job in an investment bank in Sydney. I had changed from working in a small office with an older man (as a solicitor’s apprentice in Dublin) to working in an open office with a group of younger people (in an investment bank in Sydney).

How did these internal and external factors work together? I needed some space and time to figure myself out and this is what drove me to move to Australia. Soon after I got there though, Australia started working on me. It allowed me the time to try new things, to explore different aspects of myself free from my cultural mirrors. For this I am eternally grateful. So the change came from a mixture of both internal and external factors.

2. The Expert Action-Logic

According to the theory, at the Expert action-logic the self is immersed in the logic of its own belief system (a primarily third-person perspective). The Expert meaning-maker is interested in problem solving and tends to choose efficiency over effectiveness. Can be a perfectionist, can also be dogmatic. Wants own performance to stand out. There is a beginning self awareness of durational time, 1-2 years. There is also an openness to feedback but this tends to be limited to experts in the field of their primary interest. The expert’s use of power is based on the morality of principle, “the method or process is right” and thus their craft-logic or favourite logic rules over social norms and personal needs.

Plateau

I associate my meaning-making at The Expert Action-Logic with that period in my life when I attempted to become a lawyer. In all, if I add the time spent studying law after I left college, plus the year and a half as an apprentice in a law firm in Ireland to another year and a half working as a legal executive in a Bank in Sydney, I spent five years thinking and working with the law. For that period I saw myself as developing legal expertise. Once I had the opportunity to do something else that was more interesting for me though, I jumped at it. That arose through a colleague in the Bank telling me of his idea to drive a taxi from London to Sydney with the meter running. He explained that it would enter the Guinness book of Records as the longest most expensive taxi in history and. This was what I was looking for – an adventure. With little persuasion I left the Bank, and with their financial support, went to work on the project full time.

As I reflect on my underlying meaning-making at the time, and consider the four developmental depth questions, I am aware of how much I wanted to find something that I could attach myself to. (I had hoped for years that it would be rugby, but force of injury put an end to that boyish dream, I say boyish because I wasn’t good enough anyway). I had no conscious awareness of time, at that time. My openness to feedback was also limited to those would help me address what I should be doing. What was I good at? What kind of personality did I have that might help me answer that question? My use of power was also directed to those pursuits that would maximally improve my lot in life.

Of the seven action-logic stages of development, the Expert action-logic is the one I most struggle with. Is this because I didn’t really develop an expertise at the time? Could this also explain why in my late forties I found myself completing a doctorate in adult development so I could become an expert at something? There is no skipping of stages in developmental theory but one reading of the theory suggests that I did try to skip the Expert Action-Logic stage. The other view is that I used my time organizing the Taxi Ride, and later completing an MBA degree, as preparation for a future life as an entrepreneur.

Transition.

Internal process 1 – the push that comes from a negative association with the current stage. I didn’t want to become a lawyer and I didn’t want to inhabit the kind of critical mind that is needed to be a good lawyer. Nor did I want to work in an office nor in an organization that wasn’t my own. I didn’t even want to have an expertise, as I saw it as something that would tie me down. I did want an identity though, although that could have been anything such as “Ed the adventurer”. It was perhaps also the case that I wasn’t ready for the responsibilities that the life of a professional would entail. I don’t think I was mature enough at the time.

Internal process 2 – the pull that comes from a positive association with the next stage. I wanted to create, to innovate, to be an entrepreneur and thus felt drawn to inhabit a mindset where expertise was less important than the capacity to achieve. In other words, I wanted to be somewhere else in my mind where my natural enthusiasm and positive energy could be given free reign and at that time I associated that with being somewhere other than where I was.

External process 1 – a change in role or responsibility that requires a wider range of capabilities. The decision to change from working in the bank, where I had a task role (writing legal contracts for currency swap transactions) to organizing The Great London to Sydney Taxi Ride stretched my organizing capacities and that felt like where I wanted to be.

External process 2 – a change in the external system that the individual is subject to. With a change in role also came a change in environment. I moved from a large plush office populated by highly charged and well paid bankers into a smaller office with an assistant on reduced pay.

How did these internal and external factors work together?External circumstances created the opportunity for me to meet John and hear of his idea. Internal readiness in me for an adventure brought the idea to life. So again internal and external factors working together; I was ready and the opportunity arose.

3. The Achiever Action-Logic

According to the theory, at the Achiever action-logic the self begins to operate from an expanded third-person perspective. This allows for a more inclusive approach. The self is now consciously thinking in durational time (past to future). Timeframe may extend out 2-5 years, past and future. The self also adopts a pragmatic openness to feedback provided it can serve the overall goal. This may be experienced as a form of single-loop learning that can result in an “on the spot” change in behaviour. Power is now based on the morality of authority, association and principle. The overall system effectiveness and goals are considered more important than any one system or model. This is a more ‘independent’ and systematic use of power as opposed to the more ‘dependent’ type of power at the Diplomat (on the will of others) and at the Expert (on whatever the method says). The Achiever meaning-maker is very results and action orientated but continually chases time, the self feels guilty if it does not meet his/her standards and is blind to its own shadows.

Plateau

I associated my meaning-making at The Achiever Action-Logic with that period in my life which spans working on the Taxi Ride in Australia (age 28) to when I sold my business in Ireland aged (42). In between I moved country twice, completed an MBA, got married, had a family and led two successful enterprises. This was a busy, productive and successful period. I had arrived in the adult world. I was independent and responsible. I could set goals and work effectively with others to achieve them. At one stage offered millions for my business, and with the benefit of hindsight, I should have taken it. As a friend of mine said to me later, “Ed you must have needed the lesson more than the money” and so it was.

As I reflect on my underlying meaning-making at the time, my perspective taking had expanded. I was no longer driven solely by my narrow self-interest although it was never completely absent either. I could stand back, to some extent, and resist the herd mentality of others. Equally I could see the strengths and limitations of my favourite models. My timeframe had also extended, past and future and I could increasingly see the consequences of my actions in time. My openness to feedback had similarly expanded, particularly in working with others towards achieving a goal. My use of power was also shared but never too far from my reach.

Transition

Internal process 1 – the push that comes from a negative association with the current stage. In the transformation from Achiever to Individualist, I was to experience each of the “heightened feelings of repetitiveness, irritability, constrained, emptiness, burnout, distraction, depression, angry outbursts, or existential enquiry” envisaged in the theory (Rooke & Torbert, 2005, p. 15). In fact, I recall saying to my wife Joyce that if I died, I wanted her to put on my gravestone, “Here lies Edward Kelly who wondered, was that it”? Was there not more to life than achievement and success I wondered? A first world problem indeed!

Internal process 2 – the pull that comes from a positive association with the next stage. I liked the money, the status, the acknowledgment of success, but there was something missing. Looking out to age 50 I asked myself, ‘what would I like to do and be in the next phase of my life? It was clear I didn’t want to be doing what I was doing now. It was less clear what I would be doing although it seemed to include being a part time lecturer and part time consultant, part time writer. This created a tension between where I was and where I wanted to be which in turn raised the question, ‘so what is holding you back’?

External process 1 – a change in role or responsibility that requires a wider range of capabilities. Sometime later I transferred my business to one of the younger members of the company who took it over and helped secure its future. I had come as far with the business as a I could. I couldn’t see how we were going to grow or worse even maintain it. We were in a market with no real sustainable competitive advantage. This was a salutary lesson in market dynamics. Time for me to let someone else have a go. He could not afford to buy the business from me though, and by then the business could not afford a big payout to me. The solution was that I would give the business to him and that the business would pay me back what I put in to the business over a few years. It worked. I got my headspace and a trickle of funds to keep us going. The business got a new leader to drive it forward. Ten years later the business continues to operate but the underlying lack of competitive advantage remains a feature.

External process 2 – a change in the external system that the individual is subject to. Soon after, I left my business and I started a PhD at my local University. In the process I left my car and suit behind, took up my bicycle and went to work in a very different environment. It took me a long time to adapt, much longer than I had expected. I thought the university was going to be a safe house for a brave soul like myself who in mid life was off in search of the meaning. The university had a different agenda. Suffering under its own strains it had a standard way of awarding its degrees, including a PhD, which didn’t work for me. Half way through I changed university and had to start again. I was better prepared for the second university but I struggled there as well. I think Whitehead was right when he talked about the “fatal unconnectedness of academia”. In my experience, universities are not a great place for independent thinking adults and no doubt many academics in these institutions would agree. Many of the academics I met had learned to game the system. I was no longer interested in doing that.

How did these internal and external factors work together? While the business had plateaued and I couldn’t see how we were going to grow it, my interests were also changing anyway. And so while I was outwardly aligned with the world in the sense of being independent and successful, I also felt this internal need to search for more meaning. As Thomas Merton had said, “what can we gain from sailing to the moon, if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves”. The next frontier for me was internal. I wanted to find out if there was more to life.

4. The Individualist Action-Logic

According to the theory, at the Individualist action-logic there is a noticeable separation as the self begins to explore the subjectivity behind objectivity. For some this can be experienced as a real existential crisis. In the process the self sees the relative and constructed nature of reality including one’s own (a fourth-person perspective). As the self turns inwards it has a beginning awareness of present time as well. Timeframe also expands out 5-10 years. The self now welcomes feedback as being necessary to self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of own behaviour. Use of power is now balanced with earlier forms of Coercive, Diplomatic, Logistical and Systematic power. The self is drawn to adapt, explore and create new rules were appropriate. No one approach or use of power is preferred. Relativism rules Systematic effectiveness of any single system (Independent).

Plateau

I associate my meaning-making at The Individualist Action-Logic with that period in my forties where I consciously turned inwards. I always had a curious mind, but this was different. As I recall describing my state of mind to a friend, I said, “John I have realised that I have been a doer all my life. I now want to spend more of my life as a thinker” to which he replied “and if you are lucky Ed, you will spend some of your life just being”. (Ten years later I am beginning to understand what he meant). At the time however my conscious attention was to thinking and inquiry which coincided with my PhD.

As I reflect on my meaning-making at the time, and consider the four developmental depth questions, I can see how I attracted I was to multiple perspectives on almost everything. I also wanted to know the underlying assumptions that I and others were making and how they influenced our behavior-in-action. Could I catch myself in the act of doing? My timeframe also expanded, past and future. I also reflected on what present time meant. Also, as my perspective taking expanded so did my openness to feedback from myself and others. Curiously though my use of power was less effective. I had lost the confidence and clarity of mind of the Achiever. Now being able to see so many different perspectives I often found it difficult to choose any one, all of which is consistent with a centre-of-gravity at the Individualist action-logic.

Transition

Internal process 1 – the push that comes from a negative association with the current stage. The loss of faith with the Individualistic stage came from the endless circling of ideas and perspectives. There seemed to be no order or priority to them. While this was an important reflective period in my life it began to feel quite narcissistic.

Internal process 2 – the pull that comes from a positive association with the next stage. I felt a strong pull to be more involved again. I had done my 40 days and 40 nights and now wanted to get back in the thick of things.

External process 1 – a change in role or responsibility that requires a wider range of capabilities. In 2006, I changed from working alone on my PhD at my local university in Dublin to engaging full-time in a transformative on-line course on integral theory at John F. Kennedy University in California. This connected me into a whole new community who challenged me to think in ways that I wasn’t used to.

External process 2 – a change in the external system that the individual is subject to. We also changed location from living in the centre of the city of Dublin to living on the west coast in France. Not only did we leave our home and our community though, we also renovated an old house, in a new community and in a new language.

How did these internal and external factors work together? The Individualist action-logic stage was indeed transformative. Perhaps for the first time in my life I had the time to consider the big questions in life, ‘who am I, why am I here and what am I going to be for the rest of my life’? There came a point however where some resolution, even temporary, was required. This was the motivation I needed to move on. I also needed to a new way of earning a living.

5. The Strategist Action-Logic

At the Strategist action-logic the self returns reinvigorated with a new ‘post-objective-synthetic theory’ (an expanded fourth-person perspective). The self can now add an awareness of present time to thinking in durational time, past to future. Timeframe may also extend over 10-20 years. The self also invites feedback for self-actualisation. Reflecting a kind of double-loop feedback which may lead to a second-order “on the spot” change in overall strategy and mindset as well as behaviour. Power is directed outwards towards optimizing interaction of people and systems. Concerned with reframing and reinterpreting situations so that decisions support overall principle. Most valuable principles rule the relativism of any one system (Inter-independent).

Plateau

I associate my meaning-making at The Strategist Action-Logic with that period in my life where I started to apply the knowledge and learning that I had acquired during my self-inflicted exile. I had not only physically separated from others during this time (by moving to live in France) but also emotionally separated from friends and colleagues. I was now looking to re-connect. I was conscious however of how in Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, the hero can get killed on the way back. I wasn’t a hero but I was on the way back and I wondered, how can I get back in the game without being killed?

I reminded myself that I had played this game before and now just needed to find a new position to play in. I felt I had something new and interesting to offer on adult development but wasn’t sure where to place it. My awareness of time was now both long and short as well as appreciating the ‘no time’ in present time. I was open to multiple sources of feedback, from myself, from others and from the world at large. My use of power had also changed. Whereas before I had always backed myself, I no longer felt the urge to be in charge. I was happy to explore sharing the platform with others and sense our Inter-Independence.

Transition

Internal process 1 – the push that comes from a negative association with the current stage. My internal motivation to change arose from experiencing the limitations of the theories and concepts that I had become so attached to. Was I suffering from “man with a hammer syndrome” I wondered? To a man with a hammer everything looks like a nail. I found myself looking at everything from an integral and developmental perspective. Was this getting in the way of me seeing what was actually arising?

Internal process 2 – the pull that comes from a positive association with the next stage. The pull came from wanting to operate in a more fluid way. What would it be like to turn up and be present to what was arising free from all theories and concepts? This seemed a possibility at the Alchemist action-logic stage of development

External process 1 – a change in role or responsibility that requires a wider range of capabilities. My External motivation to change came from a practical need to earn a living. We are six people and we need a corresponding amount of resources to support our lifestyle. The question now was, ‘what could I do to attract sufficient resources to meet our family needs while also doing something that was authentic for me’?

External process 2 – a change in the external system that the individual is subject to. The major change that occurred was that I left the unfamiliar territory of academia and returned to the more familiar territory of the market place. I was now back where I started and hopefully seeing it through new eyes. Was this journey TS Eliot spoke of? “The end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”?

How did these internal and external factors work together? The practical need to find a way of earning a living is very real. In this respect my current needs are aligned with most people I come into contact with in organisational life. Internally though I feel I am serving something else. As William Blake put it, “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.” I not only want to know and understand more, but I want to experience it and having done that to share it with others who might be interested.

6. The Alchemist Action-Logic

At the Alchemist action-logic the self begins to see the limitations of all representational maps, including maps of development such as this one. The construction of the ego and its influences over one’s life becomes more transparent and is seen as a limitation to further growth (a fifth-nth-person perspective). ‘Knowing’ is experienced in the more direct sense of experience. The self can now also experience a three dimensional awareness of time (durational time, non-durational present time and seeing oneself living in the present among others intentionally influencing one anothers’ futures). Time-frame may extend over 100 years. The self views feedback as a natural part of living systems. Open to a kind of Triple-loop feedback, which can lead to a third-order “on the spot” change in overall vision, as well as behaviour and strategy. This can also dissolve into a sense of connectedness to a ‘whole’ (Starr & Torbert, 2005). The self may also practice a type of mutually-transforming power which looks to create transformational opportunities for self and others. Deep processes and inter-systemic evolution rule earlier principles (inter-independent).

Plateau

I associate my meaning-making at The Alchemist Action-Logic with where I think I am right now, albeit not all of the time. Wittgenstein said, “when you get to the top of the ladder, kick it away”. I feel like kicking away the ladder as my attention is drawn to the very nature of things as they are rather than to my personal stage of development within them. I am fascinated by questions of beingness and whether it is possible to live free from my constructed nature. The willingness to consider multiple perspectives hasn’t changed, just my attachment to them. My awareness of time includes me actively thinking about co-creating my own future. My openness to feedback has also tuned me into my own hubris and the presumption that I can be of help to anyone. Thoreau rings in my ears, “if I knew a man was coming to my house with the express intention of doing me good, I should run a mile”. My use of power also feels less relevant as I no longer seek out power for itself preferring to be present to what is arising and with whoever it is with.

What is my work now I ask myself? This is the question that keeps me awake at night. When I worked at the Bank my role was clear. When I ran the Taxi Ride project the goal was clear. When I had my own business the objective was clear; sell more phones. When I did my PhD the dissertation was the main output. In each case there were signpost telling me what to do. That’s no longer the case. I want to be a philosopher, but not an ivory tower philosopher, a practical philosopher who can ask the questions, challenge underlying assumptions and facilitate deeper levels of enquiry. Breaking up the soil allows new activity to grow. I enjoy doing this in a business environment as I know the language, understand the rules, appreciate the subtleties. In the process, I can help leaders improve their leadership by focusing on their development and I can help them with their development by encouraging their self-inquiry. “He who knows others is wise: he who knows himself is enlightened” said Lao Tze. What would it be like to have wise leaders, even enlightened leaders? Is it too much to shoot for? If it’s going to happen the development must come first.

Discussion.

To sum up, completing a Developmental Autobiography has helped me see; (a) my underlying internal meaning-making has changed and developed over my adult life and has directly influenced what my attention was drawn to and what actions I took ,(b) while both internal and external factors have impacted my transition from one stage of development to the next, the internal factors were nearly always more important, (c) that not all transformations were equally important; the really significant transitions were from the Diplomat to Achiever and from the Achiever to the Strategist, (d) in my case, and as the theory would predict, my age and stage of development are related, (e) again, as the theory would predict, my stages of development follow the predicted order of development in the theory, and finally (f) compared to other measures of development, such as the LDF, GLP and SCTi, a Developmental Autobiography is both a measure of development as well as a developmental practice.

This last point is important. The very act of completing a Developmental Autobiography is a developmental exercise. It is not really a test. Nor is it an answer to the question, what stage of development am I at, and yet the process of completing a Developmental Autobiography enables you to explore what platform you currently view the world from. In addition, it gives you a new perspective on old experiences that may continue to cast their shadows to to-day. Through this process of self-examination you may get to see the extent to which your nature is constructed. From this you may find yourself asking, ‘if my nature was constructed in the past, and it has changed and developed over time, how is it being constructed now’? This brings you right up to date with yourself in the present.

The process of development however is tricky. It can be lonely and painful and full of all those things we don’t want to experience; dis-comfort, dis-ease, in-security, not knowing. And yet we also sense that there is no change without discomfort. As John Harrison says, “until the discomfort of where you are is greater than the fear of where you need to be, no change will occur”. Aldous Huxley captures this well in The Doors of Perception when he says:

“The man who comes back through the Door in the Wall will never be quite the same as the man who went out. He will be wiser but less sure, happier but less self-satisfied, humbler in acknowledging his ignorance yet better equipped to understand the relationship of words to things, of systematic reasoning to the unfathomable mystery which it tries, forever vainly, to comprehend”.

A Developmental Autobiography also takes time to complete although I now see it as a selfless act, one that not only benefits you but hopefully others as well. You can’t complete a fifteen minute on-line survey of your development though. You have to do the work of inquiring into yourself. No-body else can tell you who you are and how you have developed. Better that you explore your own stages of development. Even then it doesn’t really matter whether your underlying meaning-making fits into one stage or another as we are just using a ‘psychological lens’ on development. What is more important is that you start the inquiry process. A Developmental Autobiography is there to help you. Where it goes from there is no one else’s business.

Also, there is no guarantee that the effort will be worth it. As Huxley says, you may be wiser, but less sure, happier but less self-satisfied. Each new stage presents its own opportunities and challenges. A change in your external environment may cause an internal change in your development, which can reveal other aspects of yourself that you have happily forgotten or are not that interested in exploring. People often say to me, ‘I don’t want to start looking in because I am afraid of what I will find’. They know there is stuff grumbling away, but as long as it is chronic rather acute they can live with it. With a self-authored Developmental Autobiography you are however in charge. You dictate the pace of your own inquiry and that can feel quite empowering.

Epilogue

This completes this current series of articles on my adult developmental research. As mentioned in the introduction, I have used an Action Inquiry framework to explore my research in the first-, second- and third-person; ‘what are the third-person objective findings from the research’, ‘what are the second-person implications of the research for the field of leadership studies’ and ‘what first-person impact did the researcher have on me’? Of these, the second- and third-person voices are most often heard in academic research. The first-person voice is usually silent or dismissed lest it interferes with the objectivity of the findings. Yet as I review my own research I wonder how could that be? My ‘not so invisible hand’ was present at every stage: I chose the topic, I selected the data, I designed the method, I applied the theory, I interpreted the results, and all within the context of my personal and professional interest in adult development.

As reported in the first article, I took a random sample of 32 examples from across Buffett’s adult life and tracked the changes in his underlying meaning-making by looking at his ‘perspective taking, awareness of time, openness to feedback and use of power’ (the four developmental variables). From this I established the developmental depth in his actions and indexed it back to what it said in developmental theory. It was very clear just how much Buffett’s meaning-making had changed and developed over his life. In addition, I also looked at how other factors also influenced his actions: his nature (intelligence and temperament), his nurture (favourable background and education, early introduction to Ben Graham’s investment method, influence of significant others, etc.), available opportunity and circumstance (as Buffett acknowledges, “if I had been born in Bangledesh in 1930 instead of Omaha Nebraska, you would never have heard of me”). These and other factors are central to any understanding of Buffett’s life and success, but we already know this. What is new is our understanding of Buffett’s development and how it impacts his success, particularly as a leader.

In the second-article I looked at the second-person implications of the research for leadership studies. Talent, opportunity and circumstance go so far in explaining Buffett’s success as a leader – the missing ingredient is his development. It is difficult to read my research and not conclude that Buffett’s development impacted his leadership and the leadership culture he and Charlie Munger created at Berkshire. They talk for instance of ‘a seamless web of trust’ and how ‘love not fear’ drive their leadership culture at Berkshire, but these are not words you see anywhere in Buffett’s early approach. Nor do they have anything to do with his intelligence or temperament. These are topics of development. As I said earlier, Buffett may indeed have been hard-wired for success as an investor, but he was not hard-wired for success as a leader. Rather, while opportunity and circumstance played their part, he became a successful leader through his own intentional acts of learning and development. This is the message of hope for those of us who wish to improve our own leadership in whatever leadership role we find ourselves, as a parent, a teacher, a community worker or workplace manager. We cannot change our nature or nurture, and by and large our circumstances are beyond our control, we can play a part in our own our development which in turn impacts everything else.

Finally, in this third article I report on the first-person impact the research had on me and my development. How had I changed and developed over my adult life? And where am I now? Stepping back I now see an ‘Ed the Developmentalist’, if there is such a description, someone interested in shining a light on the developmental process for others. For instance the publishers of this article, Mark McCaslin and Russ Volckmann have asked me to write a book on Warren Buffett’s development and how it impacted his leadership and that is where I shall now turn my attention. This third article therefore represents a kind of closure for me because I now want to write in a different way. These three articles have been an important stepping stone though. If you find my current writing difficult you should try reading my thesis. Unbelievable. I now see how difficult it is for people to absorb abstract concepts such as action-logics. So, if I am going to write a more readable book, for a wider audience, I need to change the way I write. I need more story telling, more images and metaphors, less concepts and theories. So that is what I want to do now, tell the story of Buffett’s development and its impact on his leadership in a common sense sort of way that will allow others come to see why this might be relevant to them. So more to follow……

Appendix 1

Table 3: Developmental Variables

About the Author

Edward J. Kelly (BA, MBA, Ph.D) is aged 53 and lives in Dublin Ireland. Over the years he has been an adventurer, a businessman and a researcher. As an adventurer, he entered the Guinness Book of Records in 1990 having organised and participated in the longest most expensive taxi ride in history from London to Sydney. As a businessman he founded and managed his own company in the telecoms sector and as a researcher (last eight years) he has explored various approaches to leadership development and completed a PhD on one of the world’s most successful investors and business leaders, Warren Buffett. He now works as a facilitator helping individuals, teams and organisations transform themselves, their networks and their businesses.

Great article Ed. Spare, conversational, yet always grasping the essence. Above all generous, vulnerable, and sharing. A fine example of the saying that the candle is not there to illuminate itself (although in this case it seems it also does!).