Tam Lundy

“Our best hope for the future is to develop a new paradigm of human capacity to meet a new era of human existence”.

Sir Ken Robinson

Generative change: An introduction

Tam Lundy

These days there’s lots of talk about adaptive change and adaptive leadership.

Framing adaptive leadership as a more adequate response to complex challenges, Harvard University’s Ronald Heifetz points to a common blind spot: the assumption that complexity can be tamed through technical problem solving. In future, he advises, leaders must be better prepared to embrace complexity, navigate uncertainty, and respond adaptively to the challenges that pervade today’s world.

But here’s an important question for 21st century change leaders: Will adaptive change approaches offer sufficient flexibility and guidance to leaders working to generate higher levels of health, well-being and healthy development in people and in communities?

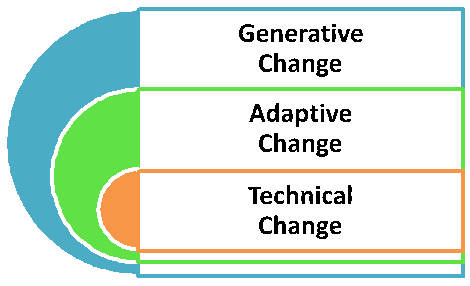

This leadership tip points to a third practical pathway: generative change leadership.

Here’s the story: After years of professional experience in diverse organizational and community settings, I can vouch for the growing complexity that impedes typical efforts to catalyze positive change. I have also observed that the language with which we describe leadership objectives is inadequate for many current and emergent needs. So, while incorporating Heifetz’ categories of technical and adaptive leadership, I’ve found it helpful to add a third – leading generative change.

Choosing the best-fit change approach

Here’s a brief summary of technical and adaptive approaches to change:

Technical change is the best fit when:

- The problem is clearly defined;

- The problem-solving solution is well-known;

- The needed skill-set can be learned;

- Current ways of thinking are adequate for the complexity of the task;

- Our change goal is to fix the problem in order to maintain the system.

Adaptive change is the best fit when:

- The change challenge is complex;

- There’s little agreement on the problem, let alone the solution;

- The way we’ve always done things no longer works – innovation is required;

- Old ways of thinking are no longer adequate – what’s required is a

change of mind;[i]

- Our change goal is to foster resilience and equilibrium in the system by adapting to changing (and often difficult) life conditions.

Generative change: A practical addition to the change leader’s toolkit

While an adaptive approach offers more options than technical leadership, many change objectives can’t be met by adaptive means alone. And that’s where generative change comes in. It’s the dynamic means by which we focus attention on challenges and opportunities, and cultivate more of the life conditions that promote individual, collective and planetary thriving.

Generative change is the best fit when:

- Our aim is to foster health, well-being & healthy development, now and for future generations;

- We’re paying attention to problems and potentials … in people, in organizations, in communities;

- Resilience is necessary, but not sufficient for our purpose: higher levels of thriving for people, and for the planet;

- Our change efforts require adaptive resilience and intentional generativity;

- Our change goal is equilibrium, plus nudging the system toward a preferred future.

Here’s an example: Like most cities, Vancouver has upscale neighborhoods and inner city neighbourhoods where poverty reigns. You’ll find community gardens in both. These collectively-constructed garden plots make a significant contribution to the health and well-being of a community; along with carrots and cucumbers they generate beauty and belonging, creativity and contribution, self-sufficiency and association, citizenship and good governance. Community gardens are an elegant exercise in place-making: public space with a salutogenic[ii] purpose.

Community gardens offer a vivid example of generative change in action. And they illustrate the value-added nature of generative change, incorporating the best of technical and adaptive skills while adding generative perspectives, objectives, and tools. Community gardens make good use of technical problem-solving skills: for example, participants share their knowledge of soil chemistry, weed and pest control, the best time to pinch and prune. They also meet adaptive needs; community gardens are often promoted by health authorities in response to food security concerns, giving residents access to high quality, locally-grown food at a fraction of the cost of produce shipped across a continent. What’s more, they serve a generative purpose: thriving. They help to create healthier, more equitable and more sustainable life conditions for individuals and for communities, now and into the future. And, because gardening together has become a sought-after activity, equally desirable in affluent neighbourhoods and the poorest postal codes, it helps to reshape local social structures and culture in ways that promote higher levels of health, well-being and healthy development.

Generative change: The key to thriving

Given that many are only now discovering adaptive change, is it wise to add generative change to the menu of change technologies? Doesn’t adaptive change cover enough bases?

I think not. While adaptive change is helpful for maintaining the health and stability of a system, for example, a generative approach focuses on the potential of the system, on what the system can become. Here, the equilibrium sought by adaptive change approaches is enlivened with a new wave of possibility: a healthier future for all. In other words, it’s a salutogenic approach to change-making, generating increased levels of health and thriving throughout the entire system.

Thriving is a generative process; to thrive means to grow or develop, to progress. In other words, thriving is less about balance, and more about becoming. So thriving doesn’t merely describe a state of health but, also, healthy human development. While integrally-informed leaders acknowledge the causal interrelationships among health, well-being and healthy human development, in most sectors it’s not yet on the radar. Bringing attention to development in adults as well as children, and to the ways that humans actively influence evolution, generative perspectives on change leadership help to bridge this gap.

Evolutionary eyes on leadership

According to my dictionary, generate means to “to be the cause of; to bring into existence.” And change, of course, means “to make different.” Generative change, then, is a creative act: purposefully emergent, fostering healthy development in self and society, now and for future generations. Erik Erikson’s concept of generativity provides a helpful foundation, described as “somewhat akin to creativity, but it refers specifically to the mature adult’s contribution to the well-being of future generations” (as cited in Joiner, B. & Josephs, S., 2007). This understanding of generativity also accords with Paul Tillich’s description as “the drive of everything living to realize itself – with increasing intensity and extensity” (as cited in Kahane, A. 2010). Or, simply, Eros.

These perspectives, of course, arise from an evolutionary worldview, an understanding that, in Steve McIntosh’s (2012) words, we live in a “universe of progress and purpose.” While generative processes are an inherent aspect of evolution, awareness of human participation in this process is a relatively recent emergence. Some call this conscious evolution; for Barbara Marx Hubbard (1998), the purpose of conscious evolution is “to learn how to be responsible for the ethical guidance of our evolution.” It is, she proposes, “a quest to understand the processes of developmental change, to identify inherent values for the purpose of learning how to cooperate with these processes toward chosen and positive futures.”

Purpose is important. And when talking about purpose, I find it helpful to quote Dee Hock (1999): “To me, purpose is a clear simple statement of intent that identifies and binds the community together as worthy of pursuit. It is more than what we want to accomplish,” he notes. “It is an unambiguous expression of that which people jointly wish to become.” Working with groups over the years, I’ve observed the change in the room when this perspective on purpose is explored, a shift from a business-like focus on objectives and strategy to a more expansive sense of possibility and intent. So far, so good. But, it’s at this point that we run into a typical roadblock, a gap between ends and means: the tendency to assume that our renewed purpose can be met with the thinking and practice tools we’ve always used.

Toward a preferred future: Aligning purpose and process

Ron Heifetz and colleagues point to this gap, and offer important advice: The most common cause of failure in leadership, they note, is to treat adaptive challenges as if they were technical problems. However, it’s equally true that we’re tempted to meet generative change objectives through adaptive means. And thus we miss important opportunities for creative input into our collective evolution – for example, to foster higher levels of health, well-being and healthy development … in people, in organizations, in communities – now and into the future.

No matter the change challenge, it’s important to discern the best-fit change technology. The approach we choose must align with our change-making purpose. Are we simply looking to maintain healthy aspects of the current system, fixing problems as they arise? If so, technical change may be all that’s required. If our intention is to seek stability in a changing world, even bounce back from adversity and shocks, then adaptive change will offer helpful tools. But if our goal is to address problems and maximize potential – with a focus on what the individual, the organization or the community can become – then generative change is the best fit. Taking important steps beyond technical and adaptive approaches, it is generative change that empowers us to become the architects of a preferred future.

Generative change leadership: Integral thinking, practical action

Generative perspectives and change processes have much in common with integral thinking and practice. A few of the hallmarks of generative change approaches include:

- Salutogenic: seeking higher levels of health in all living systems, including people and the places we live;

- Dialectical: perspectives on reality that see the generative potential inherent in contradiction, paradox and polarity, while recognizing the inherently dialectical nature of the process of change;

- Developmental: honoring perspectival diversity – from premodern to modern, postmodern and beyond – while fostering the conditions that support healthy development in children, adults and communities;

- Integrative: paying attention to each dimension of the AQAL map, connecting the dots among all of the interconnected, interdynamic and irreducible factors that support thriving;

- Evolutionary: making a stand for a preferred future, while taking action in the world.

While a generative perspective on change – salutogenic, dialectical, developmental, integrative and evolutionary – is the more natural inclination of integrally-informed leaders, generative change capacities can be learned and practiced by all change agents. These ideas, and their practical application, are explored more fully in a short e-book, Generative Change: A Practical Primer.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling The mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. & Linsky M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Hock, D. (1999). Birth of the chaordic age. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Hubbard, B.M. (1998). Conscious evolution. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Joiner, W., & Josephs, S. (2007). Leadership agility: Five levels of mastery for anticipating and initiating change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kahane, A. (2010). Power and love: A theory and practice of social change. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L.L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock the potential in yourself and your organization. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Lundy, T. (2014). “Generative health leadership: A turning point in thinking and practice.” Available: www.communitiesthatcan.org.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Available: www.merriam-webster.com.

McIntosh, S. (2012). Evolution’s purpose: An integral interpretation of the scientific story of our origins. New York: SelectBooks, Inc.

Wilber, K. (2000). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Endnotes

[i] As Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey (2009) indicate, adaptive change-making shifts our attention from the problem to the person having the problem. Adaptive challenges, they say, “can only be met by transforming your mindset, by advancing to a more sophisticated stage of mental development.” (29) However, since most development is horizontal, and more rarely vertical, translative capacity building remains an important tool for expanding skills and perspectives for leadership growth at every altitude.

[ii] Salutogenesis is a term most commonly used in the field of health promotion, but useful in all disciplinary contexts. Initially coined by medical anthropologist Aaron Antonovsky, it refers to the process by which health is created. At the center of his inquiry was an essential question: How can we better understand the factors that generate health so that we can create more of it?

About The Author

Tam Lundy, PhD, has been active in the field of human and social development since the early 1970’s. As a long-time consultant to government, organizations and communities, she has worked in diverse sectors and settings, including health, human services, community planning and education. Tam has led large-scale initiatives; advised and supported professionals, policy makers and grassroots change leaders; developed and delivered countless workshops and courses; and written extensively on topics ranging from community development, health promotion and capacity building to human development and generative change. She has also taught graduate courses in health promotion and education, and leadership for healthy change.

Tam is currently the Director of Learning at Communities that Can! Institute – www.communitiesthatcan.org. Email: tamlundy@communitiesthatcan.org.