Otto Laske

Otto Laske, Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM)

If a simple epigram could sum up what is essential to thinking dialectically it should be that it is the art of thinking the coincidence of distinctions and connections. Its essence is fluidity structured around the hard core of the concept of absence and the 1M-4D relations it implicates. – Roy Bhaskar (1993, p. 190)

To my students

Abstract

Technologically driven culture change, impoverishment of undergraduate and graduate education due to a focus on obtaining employment, and the growth of global risks of human survival in the context of the depletion of nature increasingly put an unforeseen emphasis on human dialog and thinking. They also make seemingly “academic” investigations into the cognitive development of adults (on which quality of thinking and dialog depend) pragmatically relevant with unforeseen urgency.

This introduction to the Dialectical Thought Form Framework (DTF) by way of an introduction to the Manual of dialectical thought forms (DTFM; Laske 2008), delves into the intricacies of the thought form structure of thinking and its assessment. It was primarily conceived as a tool for making dialectical thinking better known, as well as a tool for designing programs for teaching it, beginning in high school.

The teachings at the Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM) over the last 15 years reached only a small number of adepts looking for strengthening their competitive edge. Today, however, what was taught should increasingly come to be seen as an urgently needed tool for reversing risky trends found in a society increasingly based on algorithms and social-media tools. Such tools massively strengthen pure “downloading” and control-thinking rather than deep thinking, with often dire political consequences recalling fascistic antecedents.

The privilege the author has enjoyed in his teaching and research endeavors is rooted in his having studied with Th. W. Adorno (1999), founder of Critical Theory and his encounters with Roy Bhaskar (1993), founder of Critical Realism, as well as Michael Basseches, whose pioneering empirical research on adult cognitive development (1984) has inspired him to pursue research in dialectical thinking further. This introduction to DTFM is meant to spread this privilege more broadly to those eager and able to change organizations, educational systems, educational policy at the state and/or federal level, and non-profit organizations that have in mind the best for society.

For cogent pedagogical reasons, the manual introduced here is organized around Bhaskar’s Four Moments of Dialectic referred to as MELD. However, it embodies a significant difference from tradition including Bhaskar’s work itself. In contrast to most existing conceptions of dialectic – a term that derives from Plato’s Socratic dialogs – this manual puts forward a dialogical concept of dialectic as deep thinking in real time.

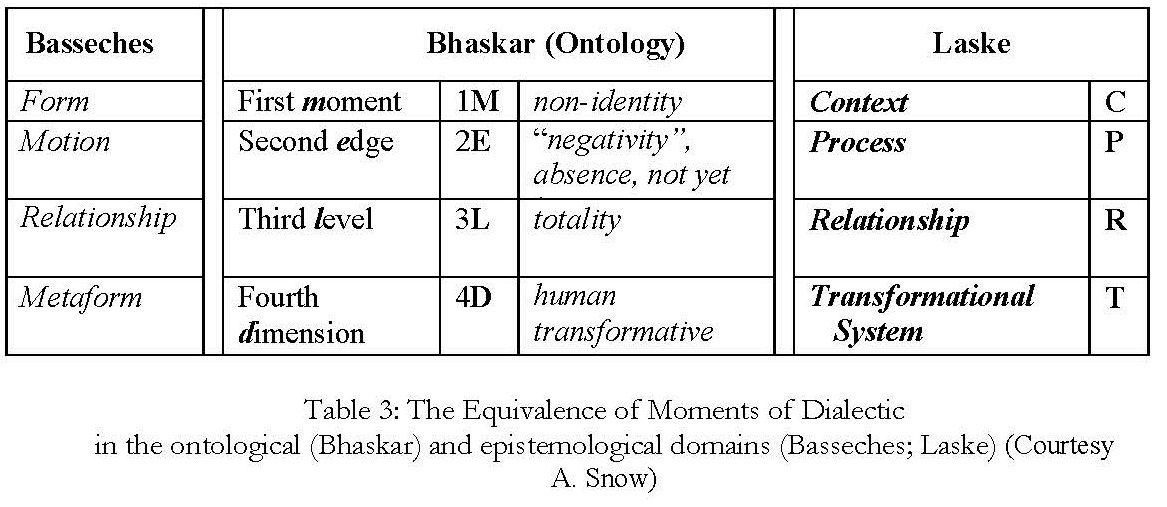

This text introduces the moments of dialectic of Critical Realism (Bhaskar 1993), together with their associated thought forms (Basseches 1984; Laske 2008; 1999), primarily as mind openers, thus as stimulants of professional as well as private discourse.

In a further step toward practicality, the dialog focused on in this introduction to DTFM is that realoccurring in real time in the attempt to reach insight into the real world, whether in teams, the class room, discussion forums, executive team meetings, or political debate. Dialog is thought to have the overriding political purpose of discovering one’s own movements-in-thought in exchange with others.

The text of this introduction covers all relevant aspects of understanding, practicing, teaching and disseminating dialectical thinking, ultimately as a tool for culture change.

Part I: Foundations of Real-World Dialog

- Welcome to dialog

- Welcome to dialectical thinking

- The purposes of the Manual

- Purposes viewed more broadly

- Closed (logical) vs. open (dialectical) systems

- Alignment with Bhaskar’s work on dialectic

- Further distinctions within dialectical thinking

- Dialectical thinking as adult-developmental achievement

- A dialectical concept of “making experiences”

Part II: Dialoguing Tools of Dialectic

- Using a short table of thought forms

- Using the compact table of thought forms

- On the nature of thought form constellations

- The relationship of scope to depth of thinking

- On the risk of sabotaging dialectical thinking

- On the risk of sabotaging logical thinking

Part III: Teaching Programs for, and Applications of, Dialogical Dialectic

- How to develop teaching programs for dialectical thinking

- Raising awareness about the limitations of purely logical thinking

- Establishing a theoretical and practical teaching framework

- Developing teaching materials: teaching as dialog

- Mentoring by way of case studies

- Guidelines for certification in dialectical thinking

- Meta-Thinking Consultations (Philosophical Coaching)

- DTF applications in organizations

- Historical note

Part I: Foundations of Real-World Dialog

Welcome to Dialog

Speaking to others pervades everybody’s life and is the basis on which we speak to ourselves internally. But not every verbal exchange takes the form of a dialog. Commands, queries, instructions, pure information exchange increasingly prevail.

Even in cases where dialog indeed occurs the emphasis is predominantly on content, on what is said, with scant attention paid to how it is said (or written), and the movements-in-thought that have led to what is said.

Even if the “how” registers emotionally, paying attention to the thought structure of what is said by a dialog partner or oneself is exceedingly rare. This manual wants to change that, for reasons indicated above.

To his great benefit, the author has been led through research and assessment, to explore a pure form of focusing on an interlocutor’s movements-in-thought in real time which is the natural outcome of carrying out interview-based, semi-structured cognitive assessment by way of the Dialectical Thought Form Framework (DTF).

He has come to think of this framework as an optimal tool for learning dialectical thinking through listening. Steeped in this kind of real-time experience, the Manual is written for the purpose, first, of recognizing, second, of reflecting upon, and third, of using dialectical thought forms in dialog. This threefold progression fits the author’s interpretation of what Hegel called “making the effort of the concept” in order to reach truth.

The Manual wants to help understand the thought forms by which people think, which is what they do before they speak and, hopefully, before they act.

Why is attending to the structures of thinking that underlie speech, and thus dialog, important in so many professional fields? Among the many reasons, two stand out:

- Speaking is not primarily a way of “describing” but actually of “creating” (constructing) reality. We co-construct reality through our dialogs, and while we may miss the mark of what is “real”, we nevertheless have the opportunity of making the conceptual effort to come as close to reality as we can in the present phase of our cognitive development as adults (see below).

- However, for various reasons partly anchored in the new internet and social- networking technologies, speaking has become separated from its experiential base, that is, one’s own movements-in-thought that give rise to “thinking”. It increasingly follows thought models that in the process of “downloading” are substituted for the experience of one’s own thinking, and thus override the latter (Greenfield 2015).

As adults, we construct the world in terms of a very personal, developmentally determined, Inquiring System. In focus in this Manual is the structure of the thinking this Inquiring System can be shown to engage in within the confines of a recorded semi-structured interview. It is here that dialectic comes into play, because movements-in-thought, when complex, transcend formal logic as well as systems thinking, and become “dialectical” (see below).

Therefore, once an interview has been systematically evaluated in terms of the four moments of dialectic (Bhaskar 1993) and their associated thought forms (Basseches 1984; Laske 2008, 20015), the thinking ego in question can be precisely described in the form of a cognitive profile called a Concept Behavior Graph (see Fig. 11 below).

Why should this be of importance beyond mere linguistics or philosophy or even cognitive assessment?

The ability to discern, through listening in a dialog, the structure of an individual’s or team’s thinking is of great practical relevance in a world dominated by formal logical thinking. This is because adult thinking is in no way restricted to logical thinking but, as shown in this introduction, extends much further, not only to systems thinking but to complex or dialectical thinking. It is this latter type of thinking that is in focus in this Manual so that the tools offered here are all dialectical tools.

Near the end of her life, Hannah Ahrendt warned us (1971, p. 167) that getting hold of what she called “the thinking ego” is nearly impossible. She says:

For the trouble is that the thinking ego … has no urge to appear in the world of appearances. It is a slippery fellow, not only invisible to others but also, for the self, impalpable, impossible to grasp. This is partly because it is sheer activity, and partly because … as an abstract ego it is liberated from the particularity of all other properties … and is active only with respect to the general which is the same for all individuals.

However, in the nearly 50 years since Ahrendt’s death new tools have emerged for making the thinking ego visible once it utters speech and its speech is transcribed and linked to the Dialectical Thought Form Framework here introduced. It is these tools this Manual introduces to. They are tools of the greatest benefit in a world posing puzzling global problems on whose solution or dissolution our survival now depends.

Following Ahrendt it would seem that this “Manual” is undertaking an impossible task: that of making the thinking ego visible, and doing so through forms of dialog such as conversation, interview and discussion.

However, language comes to our rescue here, in the sense that we can formulate abstract notions like “unceasing change” which give body to thought forms and make them memorable, and thus make it possible to link thought forms to each other, coordinating them in constellations (see below).

But language is doing much more than giving body to concepts; it is constitutive of dialog, and dialog has a close historical link with dialectic, as shown by Plato’s works referencing Socrates. Dialog is also of major political importance for our time in which “downloading” and formal logical thinking prevail, wiping out speakers’ mutual recognition (Hegel 1977).

This is the major point made in this Manual which introduces dialectic, not in its monological form as a tool for describing “the world” seemingly outside of us (Hegel, Adorno, Bhaskar), but as a tool for constructing the world through dialog between individuals and in teams.

Welcome to Dialectical Thinking

Based on what was said above, the reader rightfully expects to be focusing on what is called “thinking”. However, s(he) should be forewarned that the notion of “thinking” here explored largely runs counter to what s(he) may expect thinking to be.

The simple reason for this is that dialectical thinking in the dialogical form presented here is intrinsically and absolutely geared to understanding “how reality works”, so that reality is, in what follows, an equally important focus.

The manual thus engages three interrelated notions: dialog, thinking and reality. (There is no point in thinking in a way that is unrelated to reality.)

When we speak of how thinking and reality relate to each other, the further notion that comes up right away is truth. Here we immediately need to make a distinction between two kinds of truth: propositional and alethic truth.

- While propositional truth concerns language propositions (thus how humans talk about reality),

- alethic truth concerns truth regarding reality itself (regardless of how humans choose to talk about it).

You might, in what you say or write, achieve propositional truth and miss alethic truth entirely, as 2,500 years of philosophy clearly show.

Why might mistaking propositional truth for alethic truth be of concern in the modern world?

It might be of concern since the world you see is your own construction by way of the concepts (Liebrucks, 1964; Basseches, 1984). So if the world you construct for yourself – depending on your present level of cognitive development as an adult — is out of touch with the real world, you end up living in a fantasy world of your own, over and over confirmed by propositional truths. What George Bateson called “the gap between how reality works and the way people think” can then never be closed, and alethic truth would not even be an issue.

However, I would assert that we live in a real world, and that we are disregarding how it works at our own peril.

In fact, as embodied minds we are part of it, and disregarding it can’t even be completely carried out, except if you insist that formal logic represents the peak of adult cognitive development. (Is there life after 25? L. Kohlberg asked. The answer is no, not if you never transcend formal logic.)

This is exactly the point where DTFM, here introduced, promises its user huge benefits. The DTFM has the purpose of helping thinking individuals close the gap George Bateson is referring to. The author of this introduction to the manual does this by putting dialectic on an ontological foundation where thought and reality become inseparable (Liebrucks 1964).

Concretely this means that our conventional notion of “reality” changes to include an important new element: Absence; what is not there … (Bhaskar 1993). Absence, also called “negativity” (close to Sartre’s négatité”; 1943), is actually everywhere. What is not there or not yet there actually not only has a presence, it also has reality, or is real. Let’s take Sartre’s example.

You go to a café to meet your friend Pierre, and Pierre is not there, Pierre is absent. His absence is felt and thought as real, as a loss, and engenders concerns about what might have happened to him, beyond being simply late. If you had firmly counted on Pierre being there because you urgently needed his help, his absence would turn into an ill or even a fatality.

In short, absence addresses that dimension of reality in which we find losses, omissions, empty spaces, social ills, lies, illness, death, etc. All of these are undeniably real, and no logical thinking can erase them.

So why not address them head-on, as part of reality?

That’s dialectical thinking, and that’s where Bhaskar’s work becomes fundamental for a dialogical dialectic.

***

Dialectical thinking is here explored following Roy Bhaskar’s work on the four moments of dialectic that ground Critical Realism.

As the term “moment” indicates, they are part of a larger whole which they go into and fall out of. Simply put, they are themselves in flux making up a totality in transformation. You can’t have one moment without the other; you exist always “between” the four moments and their real-time rhythmics.

In this way moments are the elements of “a dialectic”, that of your life. They are like elements of human thought that enter and leave your mental process in real time.

Rightfully, therefore, we can see moments of dialectic as unfolding in human thought by way of specific thought forms (Liebrucks 1964 f), and if we want to be “logical” about that we can speak of “four classes of thought forms” (Basseches 1984).

But make no mistake: human thought forms are just as connected and momentary as are the moments of dialectic that are constitutive of the real world. Although you may be able to name them one by one, it would be an error to think of them as fixed and independent units of your thinking. (If you make this error, your thinking ego has no chance to make an appearance in your movements-in- thought.)

Before getting into more detail, let’s first assert that:

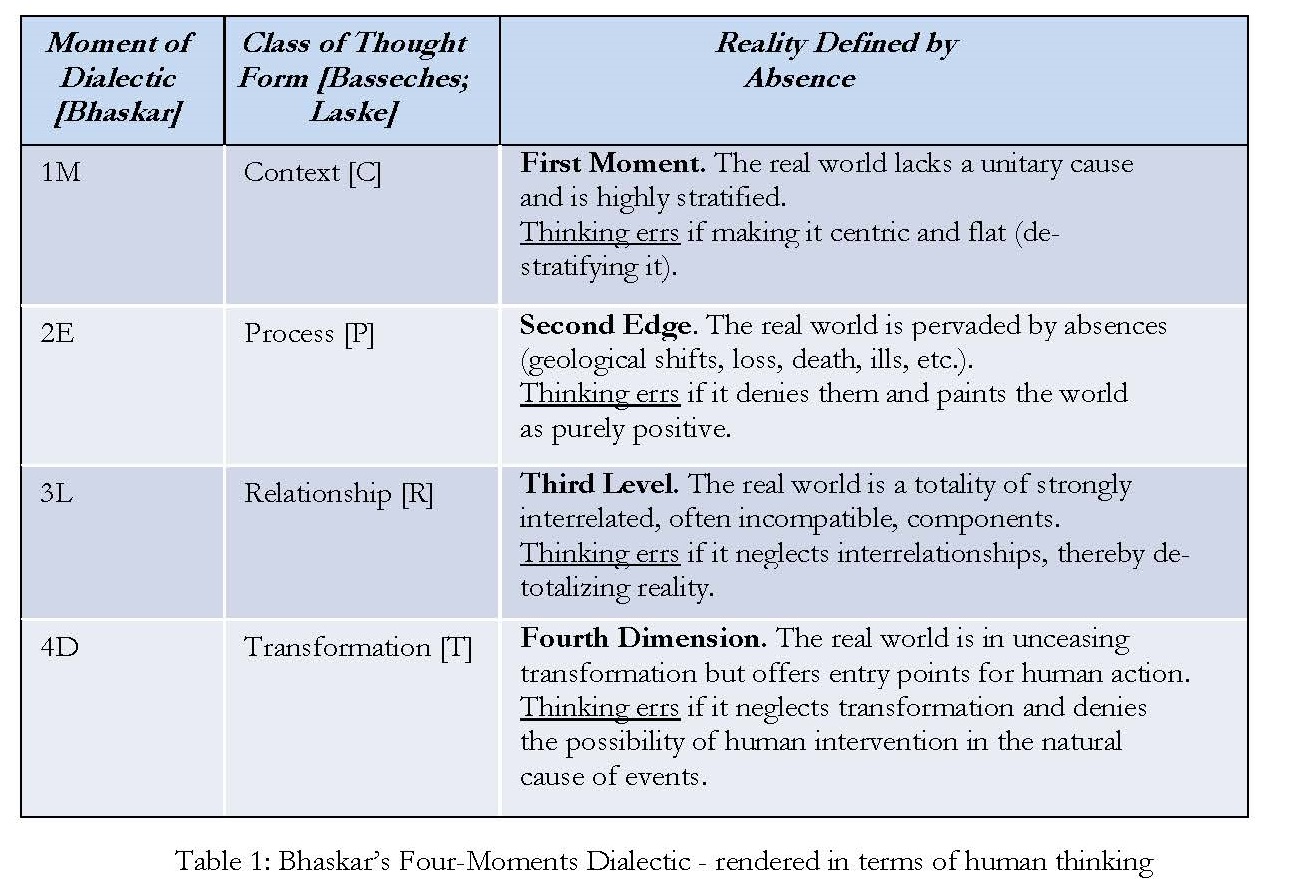

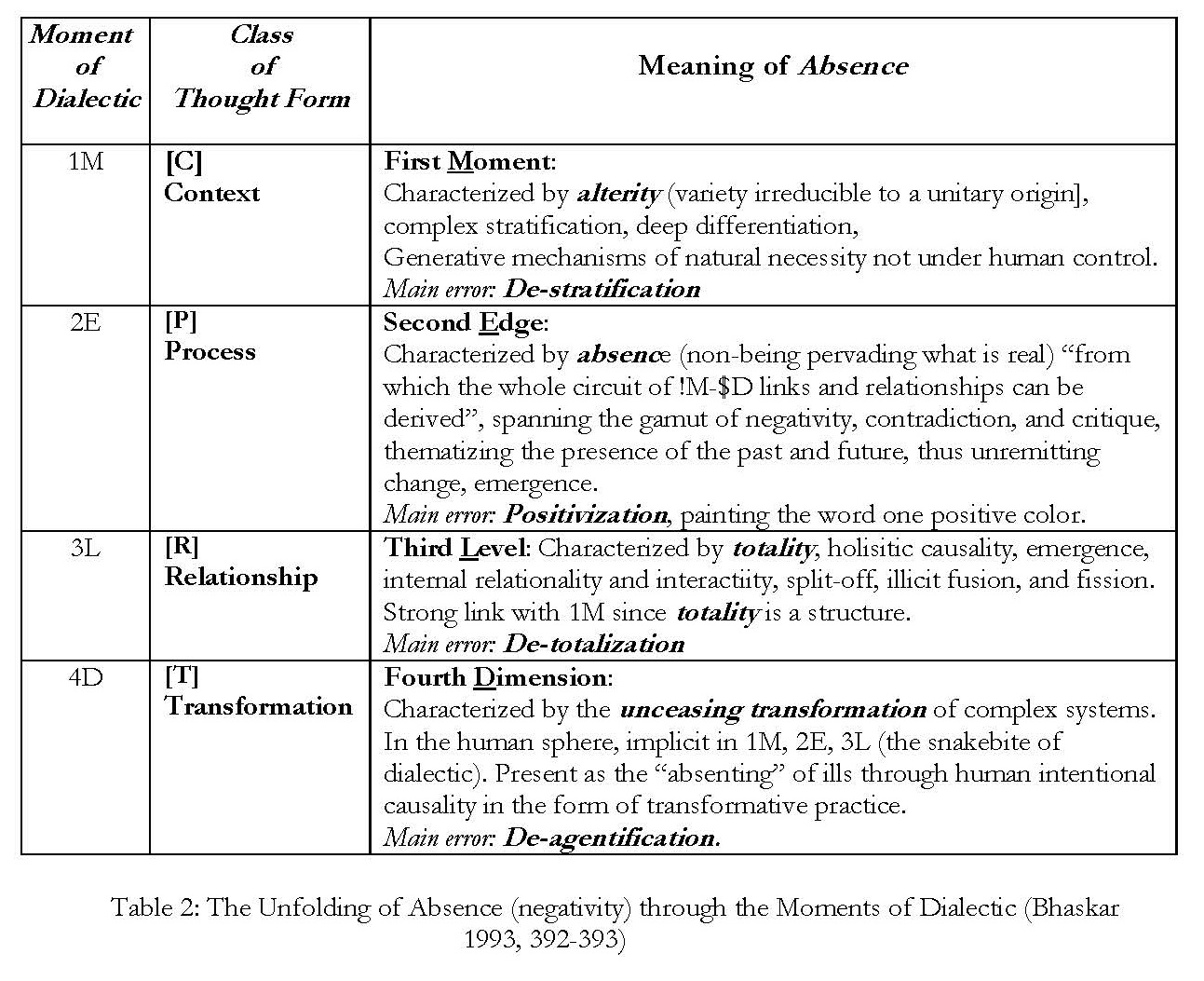

The four moments of dialectic unfold in human thinking in the form of four classes of thought forms, thereby creating an idiosyncratic Inquiring System, and that there are certain thought fallacies, listed on the right column of the table below (as “Thinking errs …”), that such a system is typically prone to (Bhaskar 1993):

As you can now see, there is no way of defining moments of dialectic, or dialectical thought forms, independently of a concept of reality that includes absences. (Think of Pierre absent from the café.) These absences show up in the world in different ways, however, which is important to take note of right from the start. See below.

The Purposes of this Manual

The purpose of this Manual (referred to as DTFM) is at least fivefold:

- To re-vitalize an ancient Western thinking tradition called dialectic on the basis of qualitative research on the cognitive development of adults since

- To help foster the pedagogy of dialectical thinking in schools, colleges, and universities at the earliest possible age (before the pre-dominance of logical and algorithmic thinking snuffs out all existing resources for holistic and systemic thought).

- To safeguard logical thinking which is beleaguered by solipsistic uses of the internet, especially social media that lead to the under-nurturing of the prefrontal cortex where conceptual thinking, moral imperatives, and personality

- To help organizations re-assess the predominantly logical models on which their business and human resources strategies are presently based, and move them beyond constructs like “theory U” (Scharmer 2016) that deliver no new thinking tools beyond systems

- To provide a manual for continued academic research on the development of dialectical thinking in adults based on DTF, the Dialectical Thought Form Framework.

These are, the reader will think, very diverse purposes. But think again! Once you realize that the world you see and consider as real is your own construction by way of concepts, and is thus a function of your present cognitive-development level, you will begin to grasp the underlying thread holding these purposes together. They all share two things:

- The perception that there is a gap between “how reality works” and “the way humans think” (G. Bateson)

- The notion that every human being, regardless of race, class, or nationality, has the cognitive resources to advance beyond logical thinking which relies on the untruth that “A is always A”, thus denying Absence (Non-A).

In fact, the realm of logical thinking compared to the scope and depth of reality is very, very small. Only human thinking can be logical, while the real world never is or could be. Nor is the real world ever static as logic requires. And it is here that dialectical thinking comes in most powerfully: it is a key to understanding not only change but transformation. To put it differently, dialectic is a discovery procedure aiming at truth in a world that is in unceasing transformation.

Combining truth and reality with unceasing transformation is, of course, a total conundrum for any kind of logical thinking, and that is precisely why we need to foster dialectical thinking – as undertaken in the manual here introduced.

These Purposes Seen Broadly

One might characterize the purposes above more broadly by saying that this manual is meant to remove dialectical thinking from the pedestal on which it has been placed by its admirers and critics alike. Once achieved (even partly), there is a greater likelihood that the pragmatic and practical benefits of dialectical thinking will be more easily seen.

Admirers have seen dialectical thinking as “critical” (critical theory, critical realism, critical thinking …), while critics have seen it as “muddling logic” and “speculative”, as well as “forbidding”. But reality, social and physical, is a good teacher, showing again and again that thought form #22 (see Table 5), for instance, which speaks to limits of stability and durability of complex systems, is actually “for real”, and that conceptions of the real world in terms of “change” (rather than transformation) are too shallow to capture “how nature works”.

This is a particularly important insight for all those sectors of society that are habitually built on formal logical schemes embodied in rigid organizational hierarchies and, increasingly, algorithmic technologies.

Although attempts at doing away with managerial hierarchies by replacing them by “circles” (Boyd & Laske, 2017) and notions like “circular economy” (De Visch et al., 2016) show a new understanding of complexity, there is still an immense amount of work to do in the way of propagating dialectical thinking in organizations and institutions, especially in teams (De Visch 2010, 2014). After all, huge challenges arise from within an unpredictable, thus logically “disruptive”, world in it is self-defeating to crave predictability.

One mighty barrier still needs to be overcome.

The culture in which “getting things done” has become more important than “thinking deeply” has in recent decades wiped out the courage to think creatively for oneself.

Such courage does not emerge quickly but requires long nurturing, and this nurturing is now largely stifled by educational systems that not only co-create but rigidly enforce the prevailing culture in which self-reflection is a “liberal arts” pursuit. For this reason, dialectical thinking has become, not only “forbidding” but bizarre. It is a major purpose of this introduction to DTFM to change this politically and otherwise risky situation.

Closed vs. Open Systems

Regarding human inquiring systems (“thinking”), an important distinction to be made is that between a closed and an open system. A closed system is a universe one can model by way of logical thinking and systems thinking – such as a system of traffic lights, or the algorithm that puts it into operation.

Such a system is closed since whatever inferences are made by or within it, whether it be by humans or machines (such as learning algorithms), do not accede to a self-reflective meta- level on which the system can be transformed in its own terms. It can only be “cloned”. While such a “quantitative” system can have qualitative effects, these effects themselves do not become integral parts of the system as they would in a living organism, for instance in human cognitive development (of which below).

By contrast, an open system is a living being, of whatever scope, existing in real time and subject to natural necessity, whether social or physical, or both. We can think of a beehive, an individual human being, or a city, or even the planet Earth in its entirety.

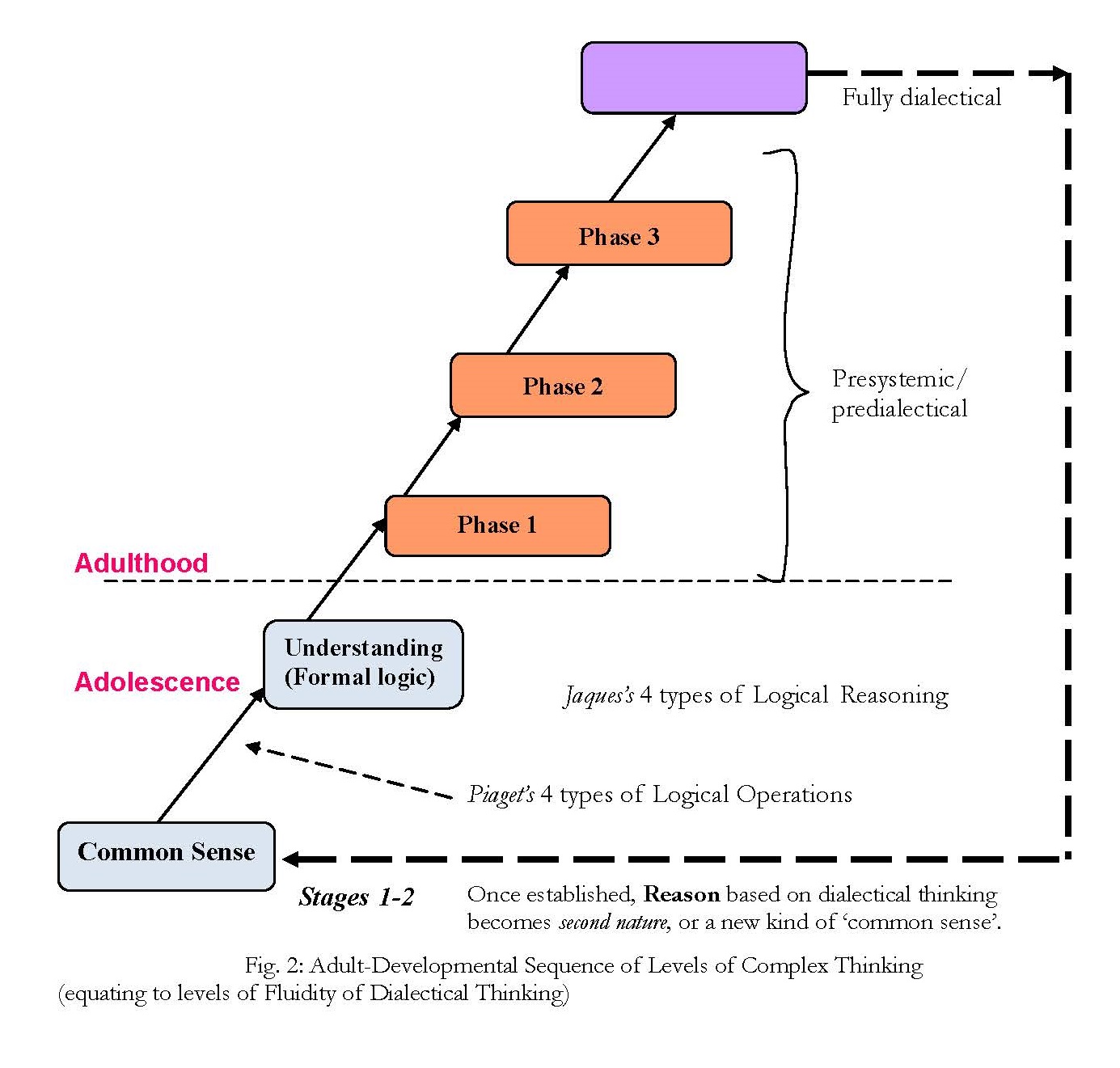

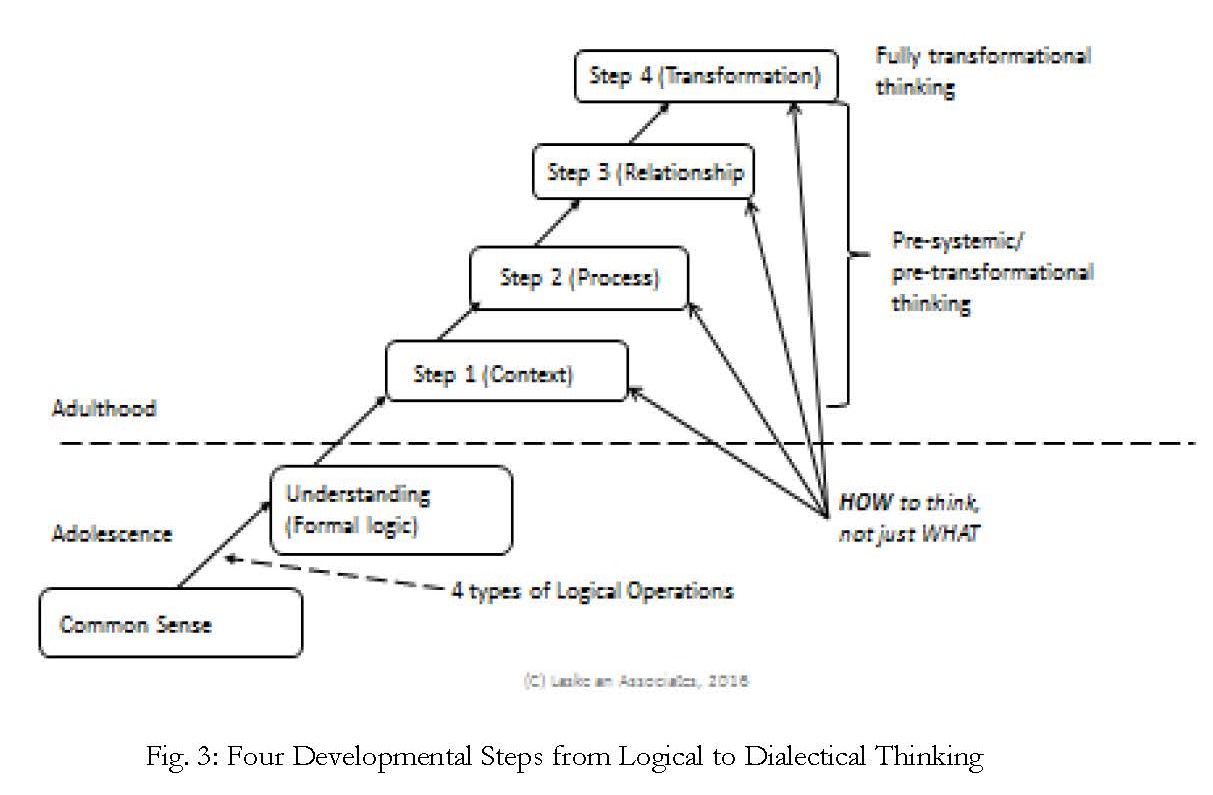

More specifically, we can think of the way individuals’ cognitive capabilities expand over their lifespan. As developmental research extending Piaget’s work since about 1973 (Riegel 1973) has shown, the progression from logical to dialectical thinking is real and can be said to occur in four phases (Basseches, 1984; Laske 2008, 2015).

Empirically, each phase is defined by a “fluidity index” based on systematically evaluating an interviewee’s use of thought forms over the course of a one-hour semi-structured interview. Significantly, the criteria of evaluation deriving from the manual here introduced provide the evidential base for the four phases shown below.

Although the characteristics of each of the phases vary empirically for different individuals, in a simplifying manner we can summarize research findings about the development of dialectical thinking by saying that the mental growth toward dialectic that occurs follows the footsteps of MELD, Bhaskar’s four moments of dialectic (1993).

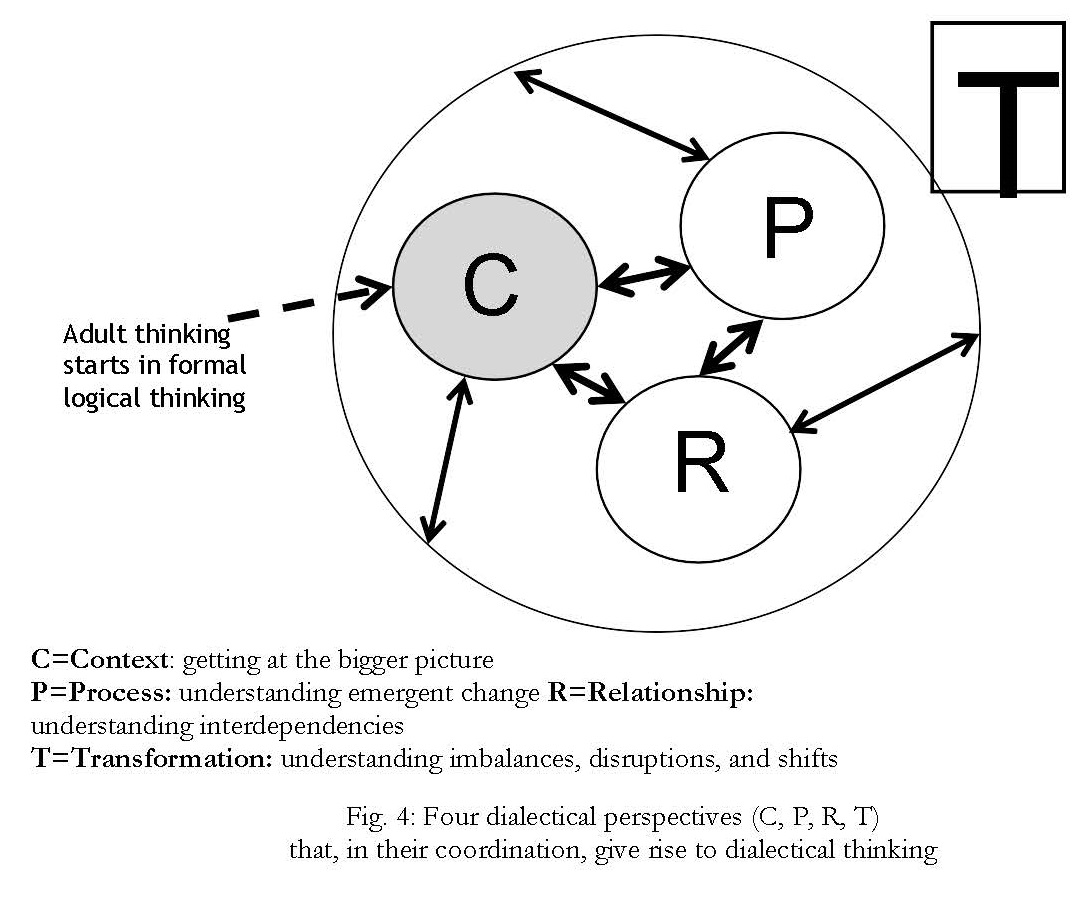

That is to say, for instance, that while in phase 1 of cognitive development individuals remain largely under the sway of 1M, or, in DTF terms, of Context thought forms (TFs), phase 2 of dialectical thinking development begins to show an increasing influx of 2E or Process TFs, showing a higher degree of realism of the thinker vis-a-vis unceasing change in the real world. Phase 3 takes the development of dialectical thinking a notch further. It extends to an understanding of the third moment of dialectic (3L or Relationships), while phase 4 shows a coordination of C, P, and R thought forms in the form of transformational thinking which grasps not only change (= P) but transformation (= T).

We thus have before us a living system that, as in the social-emotional domain of meaning making (Kegan 1982), expands its reach to higher and higher levels of complexity which, in this case, are also higher levels of (critical) realism as to how reality works, both inside and outside of oneself.

The gap between “how reality works” and “the way people think”, of which G. Bateson spoke, is an adult-developmental gap, and thus not static nor simply fate, although it is certainly a determining part of the human condition.

Alignment with Bhaskar’s Work on Dialectic

Since dialectical thinking, as all thinking, is not worthy of its name if not focused on understanding the real world, and thus on “truth” as an aspect of reality (Bhaskar’s alethic truth), this manual has been configured as a repertory of tools for diminishing the gap between “how reality works” and “the way people think” (G. Bateson).

Having adopted Bhaskar’s notion that the real is “pervaded by “absence” (non-being), or that “negativity” is equally, if not more, relevant than positive being, we are provided with tools for understanding how absence unfolds in the real world through four separate, internally related “moments of dialectic”. Important details are shown in the next table.

The Unfolding of Absence

As seen, each moment of dialectic unfolds in human thought through dialectical thought forms, in such a way that stark limitations in understanding reality arise as a function of level of adult cognitive development. These limitations show up as fallacies or structural shortcomings, above all the following:

de-stratification (C), positivization (P), de-totalization (R), and de-agentification (T; the denial of human intentional causality in producing transformative change in complicity with natural necessity).

As will become more apparent below, these fallacies are due to an impoverished use of thought form constellations, thus an undeveloped notion of Absence in its fourfold form.

While in Bhaskar’s work, the four moments are ontological principles differentiating the world’s natural necessity and associated elements of absence, in human thinking they take the form of four perspectives on what the real world is like, referred to as CPRT, as detailed below.

By “perspective” is meant, not a relativistic point of view one of which is as good as any other, but rather a way of grasping the four (ontological) dimensions of reality in their togetherness. This togetherness is referred to by Bhaskar as MELD (1M-2E-3L-4D).

According to Bhaskar, the components of MELD account for what is “real” not one by one but only together (i.e., moments are not “quadrants” as in Wilber’s writings, but are immanent in the quadrants). This has important consequences, among them a fundamental distinction between what is “actual’ and what is “real”.

For instance, “facts”, engineered and focused on by logical thinking, are man-made (factum) and are “actual” in the sense of “what is the case”, but not real. What facts lack is exactly what dialectically is called absence, that which is missing from the facts, as for instance,

the broader context of which they are an abstraction (C), the processes that make them cohere and brings them to attention (P), the intrinsic, defining relationships they have with other facts and higher elements of reality (R), and finally, the transformation of reality they are part of and abstractions from (T).

(In the real world there are no “side effects” as in an actual world, since nothing is abstracted from – as in facts, which are mere snapshots.)

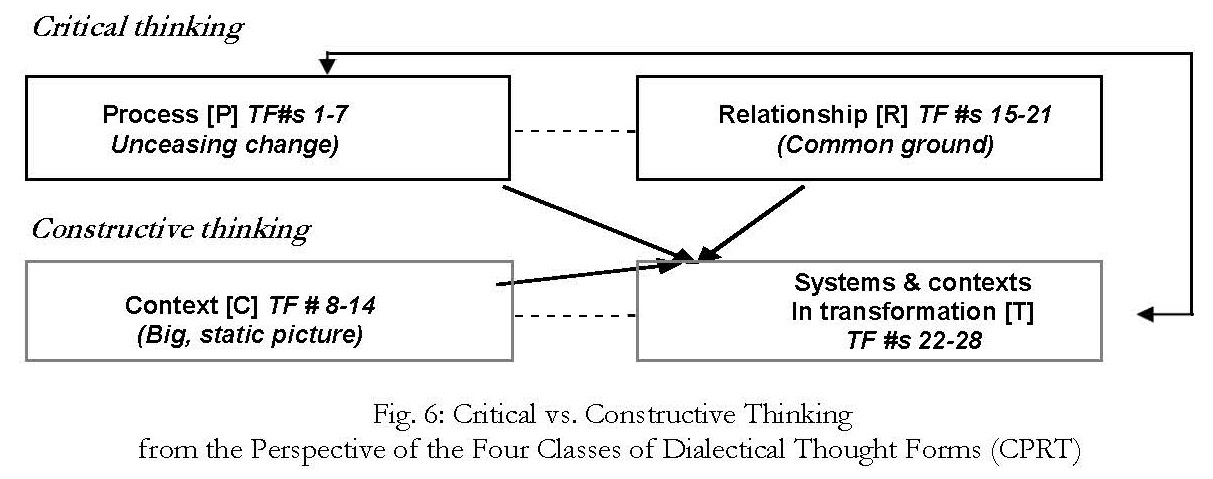

As shown in Fig. 4 below, the human mind cannot comprehend transformations by focusing on a single moment of dialectic, or class of thought forms. Only when thinking in terms of all four classes of thought forms simultaneously can reality be grasped.

Four Dialectical Perspectives

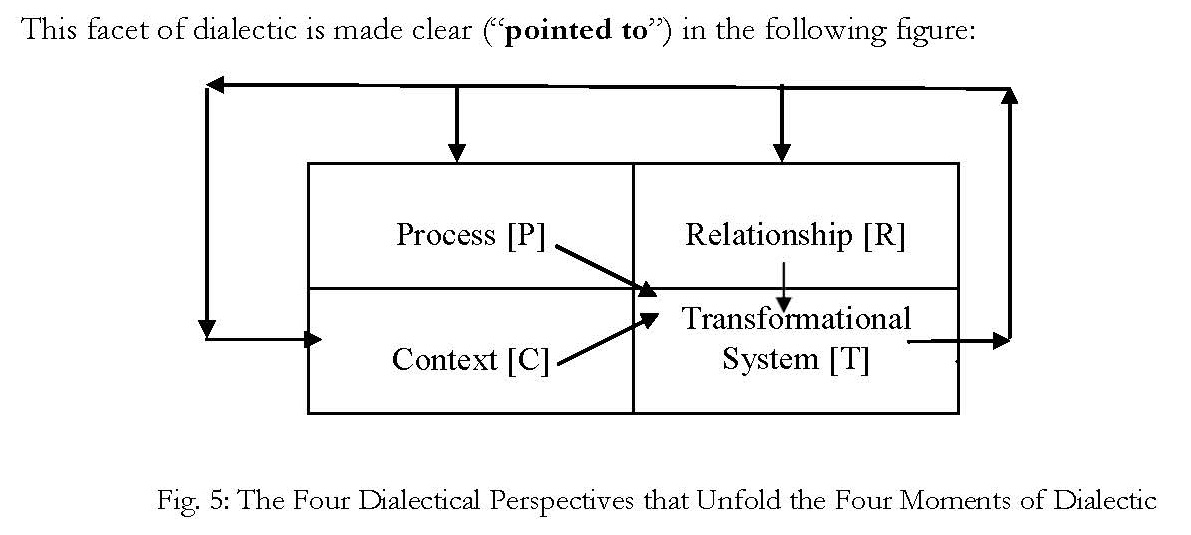

In terms of using thought forms that means that C,P,R thought forms not only need to be elaborated, but linked and coordinated with each other in constellations (of which below) for human thinking to be realistic about “how reality works”. Otherwise, the gap between reality and how humans think will remain intact, to the constant “surprise” of logical thinkers. This facet of dialectic is made clear (“pointed to”) in the following figure:

The diagram shows the four classes of thought forms which make explicit Bhaskar’s four moments of dialectic in the mind as linked by arrows. It comprises two sets of arrows:

- The internal arrows indicate that coordinating the CPR perspectives is a pre-condition for being able to hold a T-perspective on the real

- The external arrows indicate that the CPR perspectives are incomplete expressions of the T-perspective because they are intrinsically transformational but in isolation fail to fully articulate their common

Another way of understanding the meaning of the two sets of arrows in Fig. 5 is to speak of the “snake bite” of dialectic. Dialectical thinking is a way of thinking that “bites into its tail”, or is a circular system in which all MELD components and all CPRT perspectives intrinsically depend on each other. (In isolation from each other, they are mere abstractions).

That is, only together do they form a transformational system articulating reality at a meta-systemic level, that of alethic truth aligned with propositional truth: the superior purpose of all human “thinking”.

To give an example using a beehive: in each of the four CPRT perspectives the living being called a bee hive looks different, in that:

- From the perspective of C, the beehive is just a set of 10 wooden frames standing in a wooden box encompassing

- When our mind moves to the Process perspective, we become aware that C alone cannot account for the reality of the bee hive since it cannot grasp the processes (P) that bring it to life and hold it together (e.g., the seasonally changing ways the bees behave toward each other, the queen, and the external world).

- But even thinking of the bee hive in terms of C as well as P is insufficient for grasping the hives’ full existence in the real world. This is because the hive is constituted by a dense set of, not external but intrinsic, relationships without which it could not be what it is.

These are relationships that change over time, thereby fundamentally altering how the hive as a whole behaves throughout the four seasons.

In short, in the Relationship-perspective the mind can grasp the reality of a bee hive as a shared common ground of components that are “other” in regard to each other, and as “other” are together defining elements of the beehive’s identity.

- Finally, from a MELD and CPRT perspective alike, the living reality of a beehive, just like that of an individual, a city, or planet Earth, can be grasped only if the C, P, R, and T perspectives are “coordinated” with each other.

This entails that we use the four dialectical perspectives and the thought forms that unfold them as a discovery procedure in searching for what is real or what is the truth, as we do in dialog that is worthy of that name (a developmental achievement, nothing is a “given”!).

Further Distinctions within Dialectical Thinking

At this point, further distinctions within dialectical thinking can be helpfully made.

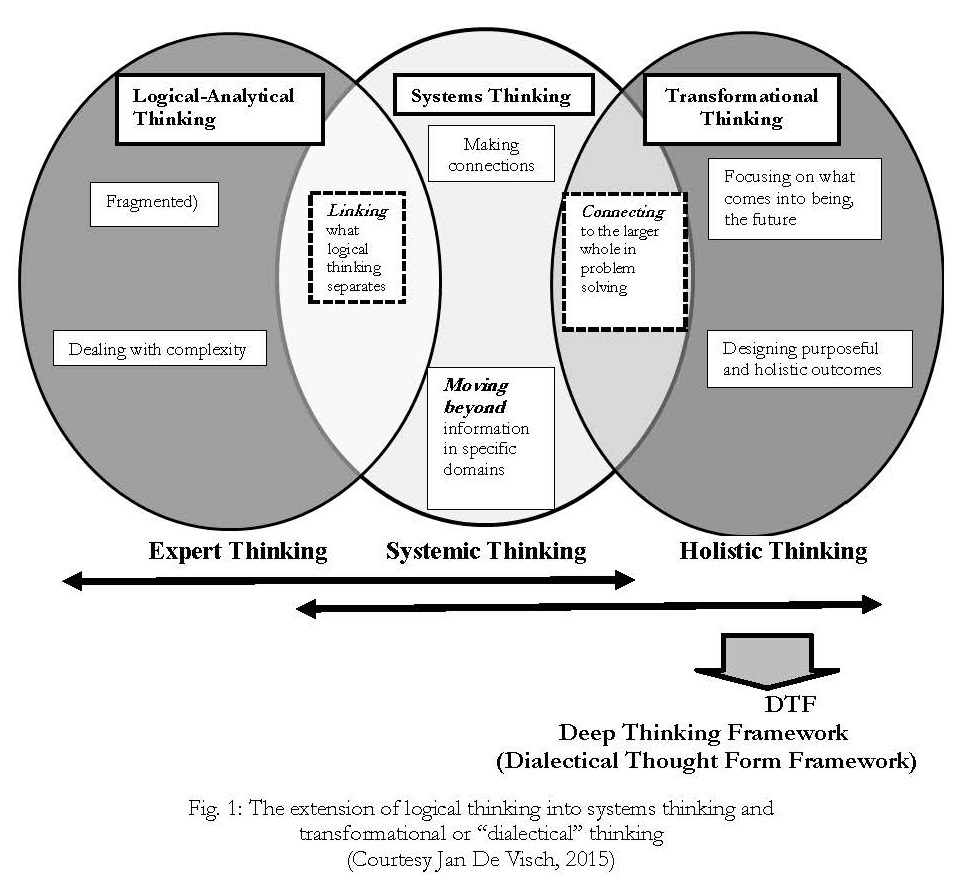

Logical vs. Dialectical Thinking

While logical thinking is bound to the Context perspective (C), systems thinking is an attempt to embrace more emphatically the relationships that connect elements of a system.

However, since what is considered a relationship in systems thinking is only an external, logical, not also an intrinsic, dialectical relationship, systems thinking goes only half-way toward a truly holistic and systemic way of thinking in the sense of dialectic.

As Fig. 6 makes clear, all four perspectives are equally and simultaneously involved in moving from actuality toward reality. With each moment of dialectic and its thought forms, what is seen as purely positive, or positively “there”, shows itself as pervaded by absences. The notion of absence has different meaning relative to each moment of dialectic:

- In 1M = Context, absence resides in the layers forming reality, regardless of whether these layers are virtual, actual, or real. They are like the spaces between words without which texts could not be coherent and understood as “texts”.

- In 2E = Process, absence is foundationally involved in the Non-A that is paired with every A, thus represents the past and the outside of A that logical thinking pushes into the shadow of Non-A and calls “false”, stopping thought in its

- In 3L = Relationship, absence lies in the differences between the parts of a whole and the parts and the whole itself that are constitutive for how the whole is shared among the parts as “other” to each other, by which alone they can share the whole and enjoy being part of

- In 4D = Transformation, these different meanings of absence coalesce into what needs to be “not there” for there to be transformation (empty spaces into which new realities flow), which makes what is “not yet” or “no longer” there the stuff that comes to be there, or the past and the future in the present (while “change” is simply a “no longer there” that fades away into nothing out of its accord).

Critical vs. Constructive Thinking

A secondary aspect of Fig. 6 should be taken note of. Within dialectical thinking, we can distinguish two different but related ways of thinking the world: critical and constructive. While an individual can think “critically” in terms of logical thinking by making inferences, critical dialectical thinking is much more radical and deep.

This is because when we think in Process or Relationship terms – in terms of how something came to be or could not be itself without what it is not itself – we essentially stop taking what “is” (that is, “givens” or “downloadings”) for granted, by tracing how it came into being and is developing further (P). Also, we are aware that whatever we are focusing on in our thoughts could not even exist without that which it excludes and is thus relative to it, and can form an integral whole only together with it (R).

Dialectical Thinking as Adult-Developmental Achievement

It is often assumed that an individual is either a dialectical thinker or not, but this is not cogent. Dialectical thinking does not spring fully grown from the head of the goddess Athena but is rather an end result reached over the course of adult cognitive development.

According to research (Laske 2008; Basseches 1984), it is based on resources maturing between ages 25 and 100. However, needing institutional nurture, such thinking does not typically develop in cultures that take scientific thinking (“Understanding”) to be the end-all of cognitive development, and is thus always a cultural desideratum, not a guaranteed outcome.

Four Eras of Human Cognitive Development

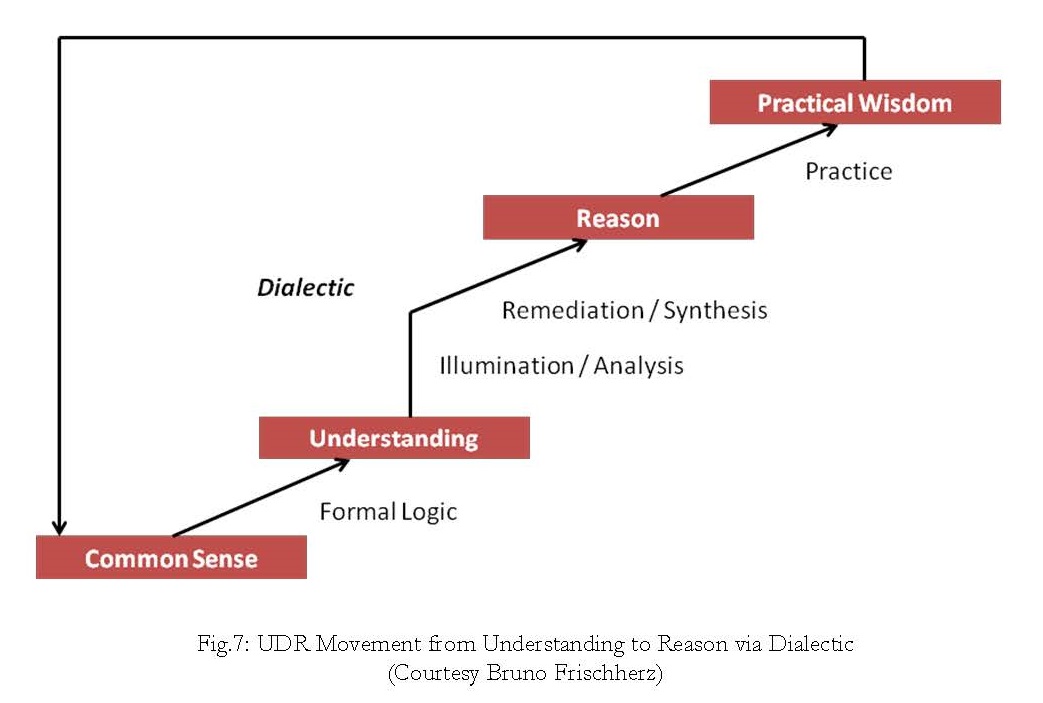

Fig. 7 below, displays in simple form the development of human thinking through four “eras”.

As seen, it leads from Common Sense into which we are born (and which we never leave behind) to Understanding on which scientific work is based, on to Reason and Practical Wisdom (of which later).

Central in this progression is the movement that begins in late adolescence, prior to the point of full maturation of logical thinking, and continues throughout life. This “developmental” movement leads from Understanding (U) via “Dialectic” (D) to Reason (R).

The UDR Movement (Understanding, Dialectic, Reason)

Let me explain the UDR movement from Understanding (U) via Dialectic (D) to Reason (R) (Bhaskar 1993, 20-33) further with the aid of Figure 7:

“Reason” is an ancient term with many meanings. Its meaning here derives from Hegel where it indicates a complex way of thinking that transcends formal logic by embracing “negativity” (absence). This is a useful term for speaking about complex thinking, as shown by Hegel himself in his Phenomenology of Spirit (1805). The simplest way to spell out the meaning of Reason, both in Hegel and here, is to say that Reason is human Understanding that has experienced absence and negativity “the hard way”, by being disillusioned again and again about what is Reality.

As in Hegel’s Phenomenology, the “thinking ego” (Ahrendt) learns to think by doing, in discrete steps, and along the way Reality again and again escapes it. This clearly entails that what is happening in the world is not “change” (moving from “A” to “B”) but “transformation” (moving from “A” to “Non-A” [negativity] and further to “A-prime”), This movement from “A” to “A-prime” via what is logically “false” (“Non-A”) is the crucial stumbling block of formal logical thinking on its way to dialectic.

The reason for this is simple: there is no preservative negation in logic whereby what is false (not there) could be preserved in a memory store to serve as a vital element flowing into “A-prime”, an integral whole born of synthesis.

The UDR movement is thus a movement that cannot be made without grasping absence, a short term for the Otherness or Non-A into which the thinking ego drops when it “thinks”. We say that a system (e.g., a human Inquiring System) has been transformed when – not despite but because of — the changes it has undergone, it has maintained its identity.

Without enduring absence in the form of change, disillusionment, loss, etc., the system could not have retained or achieved its identity. Why? Because we are dealing with a living system that remains identical with itself only by unceasingly transforming!

Understanding dialectic has just become easier! We have seen that dialectic is not just something “in the head” but something that happens to the head itself. Cognitive systems are living systems that – over an individual’s life span — pass through four eras of development referred to as Common Sense, Understanding, Reason, and Practical Wisdom (Bhaskar 1993), as shown above. Each era is characterized by a specific Inquiring System that determines the questions asked by an individual about the real world.

Developmental Inquiring Systems

Moving from one developmental Inquiring System to another, more complex, one is called “life”. While the era of Common Sense is void of any sense of conflict, in Understanding there is a firm grasp of conflict and opposition, and therefore also of how to separate one thing, A, from another, non-A. Becoming aware of the fact that things can be in conflict with each other is the achievement of Understanding. However, “Understanding” does not know what to do with conflict, declaring it simply “false” and thus getting it out of the way by denigrating it as “false”.

Preservative Negation

The thinking ego needs to take another step, one toward synthesis.

Having separated out A from non-A, it now needs to move to A-prime, and this can only be done by taking non-A – in its many different meanings – seriously. To do so means, first of all, to “preserve” it in one’s mind as something worth remembering, by putting it into a memory store. We speak of “preservative” (rather than erasing) “negation”.

Let’s use a concrete example to show this better.

Although according to Gertrud Stein “a rose is a rose is a rose”, (which is pure Understanding stuck in formal logic), really grasping the reality of Rose entails paying attention to all that the rose is not, such as its past and outside, all that is around it making it possible for it to live. This past and outside is the non-A of the rose, and only if we include it, can we have a Rose (a living system). The Rose is born of “preservative negation”. Negation also keeps it alive since to develop, the Rose will have to weather – literally – the many changes that will be upon it.

Reason

In moving from “rose” to “Rose” we have entered Reason.

Reason enables us to experience living things (not just see objects), those that have in them the core of their own decay, and who live until decay overtakes them, in a transformation called Life.

As indicated in Fig. 7, the cognitive-developmental movement of the human mind does not end in Reason but rather in Practical Wisdom.

What is meant by this is that: how logical thinking is used, changes – within Reason – where making distinctions, dealing with oppositions, and absences generally instigates a further development. We can describe the end result of this development as the complete integration of thinking with, and in, dialectical thinking.

Thought Forms

This is best explained by the use of thought forms, the topic of this manual. A thought form such as TF #1 is referred to as “unceasing change”. In different eras of cognitive development, “unceasing change” has very different meanings for an individual or group:

- For Common Sense unceasing change either means nothing, or is that which is to be expected and about which nothing can be done.

- For Understanding, unceasing change has to be “put in brackets” because scientific understanding can only take snapshots of reality, and can at best put one snapshot next to the other and compare

- For Reason, unceasing change is the order of the day, and can be inquired into by using dialectical thought

- For Practical Wisdom, unceasing change is actually not “unceasing” nor is it “change” (thus it is a misnomer); it is an enduring transformation that often shows aspects of complicity which Reason can use to act upon Reality in a way that relieves absences, such as ills, needs, and constraints.

What, lastly, is meant by the arrow pointing back from Practical Wisdom to Common Sense?

The arrow indicates the hypothesis that once logical and dialectical thinking are fully integrated (and Practical Reason is thus reached), thinking assumes a form very similar to Common Sense, only at a higher level than ordinarily realized.

The best way to think of this achievement is to see dialectical thinking becoming “second nature”, something that no longer requires much conceptual effort.

In Practical Wisdom, the “effort of the concept”* (Hegel) made all along becomes easier to make because dialectical thinking, fully mature, has become the natural way to think, with no regression into purely formal logical thinking.

[* Effort of the concept: The effort required by humans to consistently activate in their minds all of the four moments of dialectic’]

Let us now summarize what we learned about the four eras of human cognitive development.

- We are all born into the era of Common Sense and never really leave it behind, thus always stay to some degree outside of the UDR movement. Common Sense gives us precious, perception-based, knowledge that remains largely beyond conscious grasp, and is the mother soil of all subsequent cognitive development. (Example: tying your shoes, which no formal logical device, such as a computer, can do.)

- Understanding is the big next step, reached through schooling. Between 10 and 25 years of age (a long time…) we learn to master formal logic which excels at making distinctions. In this way, we can partake of the sciences, and can master more mundane things such as figure out a traffic light system in which green is always green and never red. This powerful tool can, however, become a powerful hindrance in grasping reality because the real world is not logical, only the human mind can learn to be.

- The crucial step toward seeing the light of Reason is dialectic. By understanding the four moments of dialectic and the thought forms that unfold them in the mind, it is realized that: what formal logic considers as “false”, namely “non-A”, is actually a vital ingredient of the existence of A, whatever it may be, and that one needs to move beyond “non-A” in a preservative way so that the synthesis called “A-prime” can be reached. (“A-prime” is “A transformed”, not just changed.) It is this step that assures that complex thinking in the sense of holistic, systemic, and transformational thinking can occur that is needed to move as close as possible to critical realism in one’s understanding of the world.

- However, even Reason is not fully secure since it can, depending on the individual, give up its light and return to formal logic.

Therefore, in the UDR movement, D (Dialectic) can fail and R (Reason) can be reduced to U (Understanding). It is only in Practical Wisdom that this risk of R regressing to U is overcome, because in Practical Wisdom it (D – Dialectic)has come into its own.

DTF Developmental Thought Form Framework (Deep Thinking Framework)

At this point, DTF, the Developmental Thought Form Framework, appears in a different light. One can now see that it contains all the tools necessary to move from Understanding back to Common Sense, via Dialectic and Practical Wisdom. DTF thus sheds new light on human cognitive development in its entirety, as well as on the human condition of being in the world without, potentially, ever coming close to it.

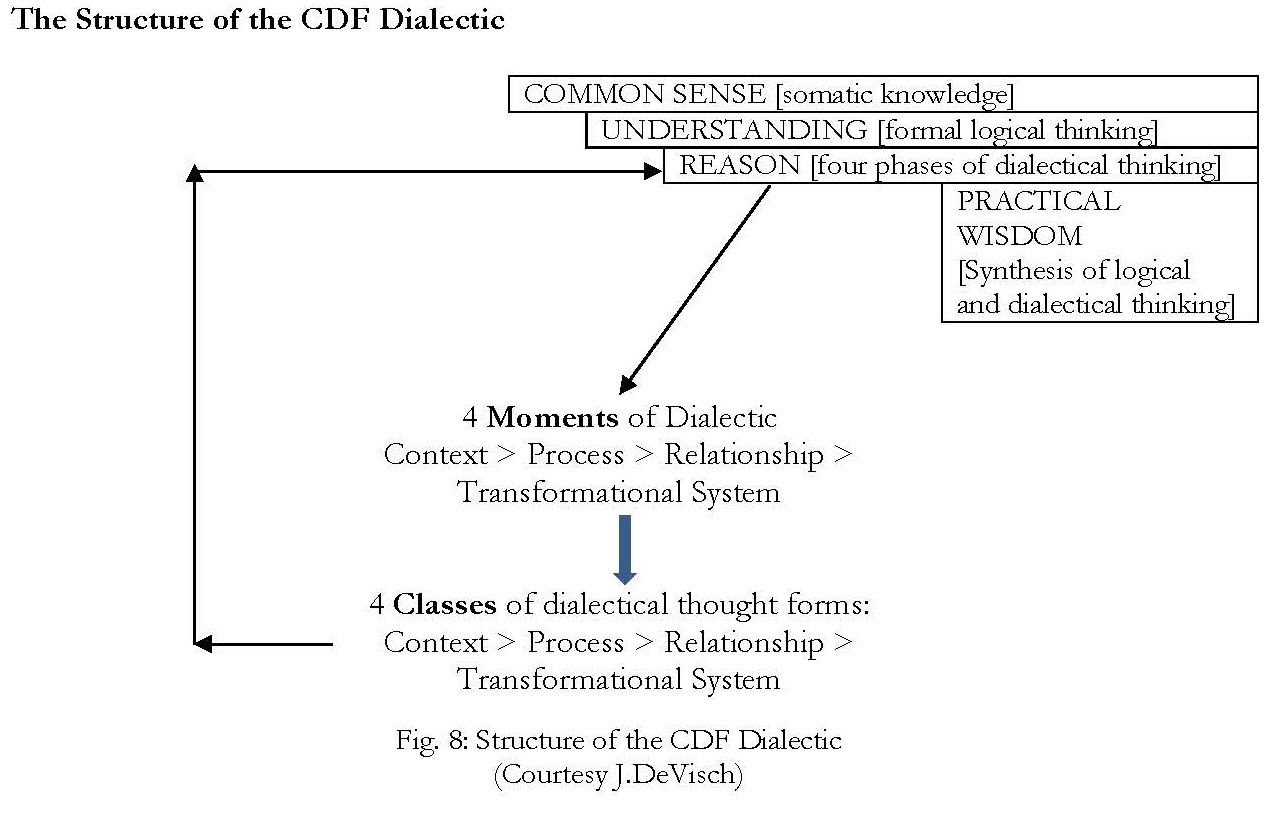

The Structure of the CDF Dialectic

The four rectangular boxes at the top of the diagram refer to the four eras of adult cognitive development that human Inquiring Systems go through. The development is grounded in the four moments of dialectic which appear in the mind as four classes of thought forms referred to in DTF as CPRT, It takes living through four eras of cognitive development to “return to life”, as Hegel says.

A Dialectical Concept of “Making Experiences”

Adult cognitive development is a process presently almost entirely neglected in our culture, except where it is seen as a matter of importance as, for instance, in organizational problem solving and decision making.

When “thinking” is taken seriously at all, the assumption is made (and demonstrated) that it equates to identity thinking excluding absence, and is the only way of understanding the real world (rather than being the most certain way of missing it). Despite of paying lip-service to “critical thinking”, our culture essentially has no notion of the existential relevance of adult cognitive development for individuals’ and society’s quality of life.

Much the same holds true for the topic of “experience”. While “experience” is much talked about as something to “exceed”, the way it comes about in individuals in structural terms is not a topic of serious research.

However, once we distinguish, as we do in the Constructive Developmental Framework, between social-emotional and cognitive development and separate these from psychological issues, we move a step further toward understanding how human experiences of the real world come about.

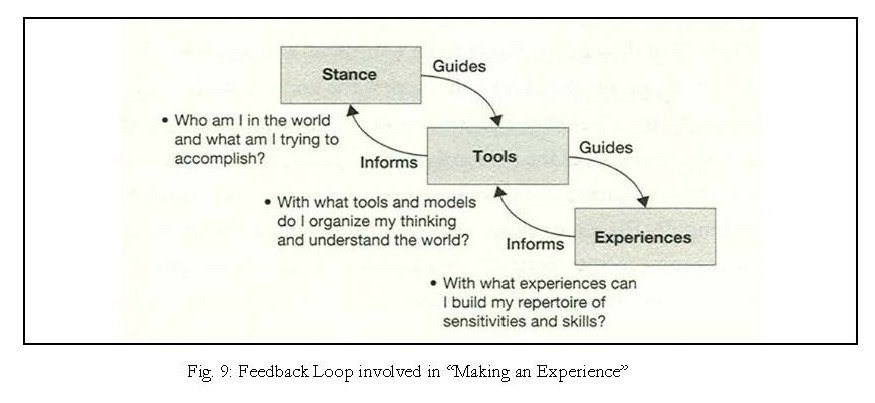

Fig. 9 shows how making experiences can be understood on adult developmental grounds.

As shown, individuals make experiences based on two interactive constituents:

first, their social-emotional Stance which equates to their level of meaning making (Kegan 1982), and second,, the cognitive Tools they are using, such as logical and/or dialectical thinking.

As shown, there exists an ongoing feedback loop linking these two constituents to each other and to experience itself. While this feedback loop is often conceptualized as “learning”, it would be more accurate to conceive of it as an adult-developmental process that enables learning.

Learning is simply not development.

Let’s take a concrete example. If you define yourself by others’ expectations, thus based on no cohesive value system of your own (Kegan’s “stage 3”): You will experience not only yourself but also the social and physical world around you in terms of dependence on others. (While this is going to be more noticeable in the social world, the way you understand your body in the world will equally be “other-dependent”).

However, once you move to a self- authoring stance and are thus grounded in your own idiosyncratic value system, the world you experience changes dramatically: You have become a smaller subject and the world has become a larger object for you. In a further developmental movement, the world increasingly becomes more than an “object”, morphing into a totality of which you are a small but constitutive part.

About the Author

Otto Laske is a social scientist and epistemologist grounded in work of the Frankfurt School linked to that of Nicolai Hartman, Bruno Liebrucks, and Roy Bhaskar. In 2000, he founded the Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM) for teaching the Constructive Developmental Framework (CDF), a synthesis of adult-developmental research from 1975 to 1995, whose cognitive component is DTF. His developmental and organizational work is based on dialectic as a real-time dialogical discipline. In his work he is influenced by Adorno, Bhaskar, Hegel, Horkheimer, Jaques, Marx, and Sartre, fruitfully combining philosophical thought with empirical assessment and research in the cognitive and social-emotional development of adults.

He can be reached at the Interdevelopmental Institute (IDM) by writing to otto@interdevelopmentals.org, or by calling 978 879 4882 (Gloucester, MA, USA). His artistic work is found at www.ottolaske.com.

Acknowledgement: I want to thank Alan Snow, Sydney, for his indefatigable editorial and moral support since 2009 regarding the publication of my writings explicating the Constructive Developmental Framework (CDF).

Bibliography

Adorno, Th. W. (2012). Critical models: Interventions and catchwords. New York: Columbia University Press.

Adorno, Th. W. (2008). Lectures on negative dialectics. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Adorno, Th. W. (1999 [1966]). Negative dialectics. New York, Continuum. [Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main].

Adorno, Th. W. (1974). Minima Moralia. London: Verso (Frankfurt, Germany, Suhrkamp 1951.

Ahrendt, H. (1971). The life of the mind. New York: Hartcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development.

Belolutskaya, A. K. (2015). Multidimensionality of thinking in the context of creativity studies. Russian Psychological Society; Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, vol. 8, issue no. 2. ISSN 2074-6857; ISSN 2307-2202 (on line).

Bhaskar, R. (1993). Dialectic: The pulse of freedom. London: Verso.

Bolman, L. G. and T. E. Deal (1991). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Bopp, M. and M. Basseches (1981). A coding manual for the Dialectical Schema Framework. Unpublished dissertation.

Boyd, G. & O. Laske (2017). Shared Leadership and Followership: How to transcend the limitations of present understandings of its nature and requirements. Chapter to be published in Distributed Leadership, Palgrave MacMillan Publishers, London, UK.

De Visch, J., K. Ulmer, O. Laske (2016). Why we need new thinking around algorithms for a circular economy (MacArthur Foundation Webinar, October). : https://www.thinkdif.co/open-mic/how-dialectical-thinking-needs-to-complement- algorithms-to-enable-the-transition-towards-circular-economy.

De Visch, J. (2010). Mental highways and behavioral pathways: the unity of thinking and doing. Wirtschaftspsychologie 1-2010, Jahrgang 12. Pabst Science Publisher, Lengerich, Germany, ISBN 1615-7729, p. 46 f.

De Visch, J. (2010).The vertical dimension: Blueprint for align business and talent development. Mechelen, Belgium: Connect & Transform.

De Visch, J. (2014). Leadership: Mind(s) creating value(s). Mechelen, Belgium: Connect & Transform.

Feenberg, A. and W. Leiss (2007). The essential Marcuse. Boston: Beacon Press.

Frischherz, Bruno (2014): From AQAL to AQAT: Dialog in an Integral Perspective. Integral European Conference, May 2014, Budapest. Online (05.12.2016): http://www.didanet.ch/wp/wp- content/uploads/2011/07/dialog_in_an_integral_perspective.pdf

Frischherz, B.; Lehmann, M. & Shannon, N. (2014). Wikipedia: Constructive Developmental Framework (CDF). Online (05.12.2016): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructive_Developmental_Framework

Frischherz, Bruno (2013a): Dialektische Textanalyse und Textentwicklung – Teil I. In: Zeitschrift Schreiben. Online (05.12.2016):

http://zeitschrift- schreiben.eu/globalassets/zeitschrift- schreiben.eu/2013/frischherz_dialektische_textanalyse1.pdf

Frischherz, Bruno (2013b): Dialektische Textanalyse und Textentwicklung – Teil II. In: Zeitschrift Schreiben. Online (05.12.2016):

http://zeitschrift- schreiben.eu/globalassets/zeitschrift- schreiben.eu/2013/frischherz_dialektische_textanalyse2.pdf

Greenfield, S. (2015). Mind change: How digital technologies are leaving their mark on our brains. New York: Random House.

Haber, R.(1996). Dimensions of psychotherapy supervision. New York: W.W. Norton.

Hawkins, R. E (1970). Need Press interaction as related to managerial styles among executives. Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1977). Phenomenology of Spirit (A. V. Miller, translator). London: Oxford University Press.

Horkheimer, M. (2014). Critique of Instrumental Reason. London: Verso.

Horkheimer, M. and Th. W. Adorno (2002 [1947]). Dialectic of enlightenment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Jaques, E. (1998). Requisite organization. Arlington, VA: Cason-Hall & Co. Jeffries, S. (2016). Grand hotel abyss. London: Verso

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kegan, R. (1982). T

King, K.S. (1983). Cognition, metacognition, and epistemic cognition: A three-level model of cognitive processing. Human Development, 26:222-232.

Lahey, L. et al. (1988). A guide to the subject-object interview: its administration and interpretation. Graduate School of Education Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Laske, O. (2016). How Roy Bhaskar expanded and deepened the notion of adult cognitive development: A succinct history of the Dialectical Thought Form Frame (DTF). Integral Leadership Review, August-November 2016.

Laske, O. (2015a). Dialectical thinking for integral leaders: A primer. Tucson, AZ: Integral Publisher.

Laske, O. (2015b). Laske’s Dialectical Thought Form Framework (DTF) as a Tool for Creating Integral Collaborations: Applying Bhaskar’s Four Moments of Dialectic to Reshaping Cognitive Development as a Social Practice. Integral Review, September 2015 , Vol. 11, No. 3.

Laske, O. (2012). Living through four eras of cognitive development. Integral Leadership Review, 2012 (August).

Laske, O. (2010). On the autonomy and influence of the cognitive developmental line: Reflections on adult cognitive development peaking in dialectical thinking. Integral Theory Conference, July.

Laske, O. (2008a). Measuring hidden dimensions of human systems: Foundations of requisite organization. Medford, MA: IDM Press.

Laske, O. et al. (2008b). Business leadership for an evolving planet: The need for transformational thinking in intercultural and international environments. Integral Leadership Review vol. viii, no. 5.

Laske, O. (2002). Executive development as adult development. Handbook of adult development. Edited by J. Demick & C. Andreoletti. New York: Plenum Press. (Ch.29).

Laske, O. (2001). Linking two lines of adult development. Bulletin, Society for Research in Adult Development.

Laske, O. (2000). Foundations of scholarly consulting: The developmental structure-process tool (DSPT = CDF). Consulting Psychology Journal no. 52(3).

Laske, O. (1999a).Transformative effects of coaching on executives’ professional agenda. Psy.D. Dissertation, MA School of Prof. Psychology, Boston, MA. Ann Arbor, MI: Bell & Howell (order no. 9930438.

Laske, O. (1999b). An integral model of developmental coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal 51(3), 139-159.

Laske, O. (1966). Űber die Dialektik Platos und des frühen Hegel. Mikrokopie GmbH München, Germany.

Liebrucks, B. (1964-1979). Sprache und Bewußtsein (Bd. 1-7). Frankfurt, Germany: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.

Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Martin, R. (2007). Opposable minds. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Mintzberg, H. (1989). Mintzberg on management. New York: The Free Press. Possert, B. (2015). http://www.integralpatterns.com/dialectical-thoughtforms.html

Riegel, K. F. (1976). Dialectic of human development. American Psychologist, 31: 689-700.

Riegel, K. F. (1973). Dialectical operations: The final period of cognitive development. Human Development, 16: 346-370.

Ross, S. N. (2010). Step into the service and challenge of dialectical thinking: A brief review of Otto Laske’s Manual of dialectical thought forms. Wirtschaftspsychologie 1-2010, Jahrgang 12. Pabst Science Publisher, Lengerich, Germany, ISBN 1615-7729, p. 24 f. See also http://integralleadershipreview.com/4708-book-review-measuring-hidden-dimensions-of-human-systems/

Sartre, J. P. (1943). L’être et le néant. Paris, Gallimard.

Scharmer, O. (2016).Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges, 2nd Edition. San Francisco, CA; Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Schweikert, S. (2010). CDF als Bildungswerkzeug für Menschen im Zeitalter der Wissensökonomie. Wirtschaftspsychologie 1-2010, Jahrgang 12. Pabst Science Publisher, Lengerich, Germany, ISBN 1615-7729, p. 90 f.

Shannon, N. & B. Frischherz (2014). Training in dialectical thinking to support adult development. 2014 Conference Session of the European Society for Adult Development.

Shannon, N. (2010a). Towards a decision science for organizational human resources: A practitioner’s view. Wirtschaftspsychologie 1-2010, Jahrgang 12. Pabst Science Publisher, Lengerich, Germany, ISBN 1615-7729, p. 34 f.

Shannon, N. (2010b). What can IDM offer the Integral Movement? Reflections on the Second ITC Conference, CA, USA.

Sherratt, Y. (2002). Adorno’s positive dialectic. Cambridge University Press.

Spencer-Rodgers, J. et al. (2010). The dialectical self-concept: Contradiction, change, and holism in East Asian cultures. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull 2009 Jan. 35(1) 29-44, doi 10.1177/0146167208325772.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic Books. Stewart, J. (2016). Laske on dialectical thinking. Book review, ILR Summer 2016.

Tenguez, A. (2008). Cognitive developmental interviewing and its effect on my consulting experience. IDM Hidden Insights Newsletter, 4(6).

Veraksa, N. E. et al. (2013). Structural dialectical approach in psychology: Problems and research results. Russian Psychological Society; Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, vol. 6, issue 2. ISSN 2074-6857; 2307-2202 (on line).

Vurdelja, I. (2011). How leaders think: Measuring cognitive complexity in leading organizational change. Ph. D. Dissertation, Antioch University.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.