Tom Murray

Tom Murray

Overview

This article began as a series of short white papers providing various types of background information about STAGES and its predecessors. Its sections are relatively independent and readers with prior knowledge should be able to skip to and read each independently, or in any order. For those new to the field, it provides an overview of theories of meaning-making development (also called ego development or leadership maturity—and which we call “wisdom skills”) as measured by the sentence completion test (SCT). For those familiar with the SCT, it provides (1) an overview of literature supporting its validity and properties; and (2) a deeper exploration of the meaning of meaning-making development. Finally we give an overview of the STAGES model.

STAGES is a new model of human development, created by Terri O’Fallon, that proposes an underlying system of factors driving the ego development and leadership maturity frameworks created by Jane Loevinger and modified by Suzanne Cook-Greuter and Bill Torbert. The STAGES model is relatively new and questions naturally arise regarding its validity and how it relates to other models. The original purpose was to provide background information for a related project—the author is developing an automated assessment tool for scoring the types of sentence completion tests (SCT) described in the article (information at OpenWaySolutions.com). The current purpose of this paper is to provide an in-depth look into background literature underlying the validity of STAGES.

The topics covered and questions addressed include:

- Overview and Summary—What are the themes covered in the article?

- Background Context and Preface—What is the larger context for this article?

- An introduction to wisdom skills and adult development—What is meant by the development of meaning-making or ego development? What are wisdom skills? Why are wisdom skills important? What is wisdom and how does it relate to meaning making? In developmental theory, what is vertical vs. horizontal growth? What are levels of development? What causes or supports development? What are some caveats and concerns one needs to keep in mind when using developmental theories?

- Defining and measuring ego development—We focus in on Loevinger’s concept of ego development and its measurement through the WUSCT (as one way to measure wisdom skill). What is a projective test? What does the WUSCT look like and how is it used? Is “ego development” one thing or a combination of related skills or multiple intelligences? How does ego development coordinate the development of reasoning (cognitive) skills and social/emotional skills? How did Cook-Greuter’s conceptions of person-perspectives and post-autonomous wisdom contribute to ego development theory?

- Internal validity of SCTs—What are the psychometric properties of the WUSCT and later SCT forms including MAP, LDP, and GLP? What has the research found about inter-rater reliability, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability? What types of modifications to the WUSCT are valid? What has research found about the vulnerability of the SCT to faking, guessing, and studying-for?

- External Validity of the SCT—How has the “face validity” or pragmatic usefulness of the SCT been argued for? How does the construct and measurement of ego development (meaning making maturity) relate to things like IQ, socio-economic status, psychological traits, and moral judgment? What does the research say about the ability of the SCT to predict or correlate with observable behaviors in leadership and personal growth and resilience?

- The STAGES Model—What is the STAGES model and how does it differ from prior models of adult ego development? How does STAGES describe development using four key dimensions drawn from Wilber’s AQAL model? What is the relationship between stages and states in the STAGES model? How does STAGES related to contemporary cognitive theories, brain theories, and Neo-Piagetian theories of hierarchical development? What conclusions can be drawn from STAGES empirical validity studies?

In terms of both theory and empirical validation, the STAGES model rests upon theory and research on the MAP/GLP/LDP assessments of Cook-Greuter and Torbert; which in turn rests upon the large body of research on Loevinger’s theory and instrument—the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT). The quantity of research supporting the strength of the WUSCT and its ego development model is one or two orders of magnitude larger than that of the MAP/GLP/LDP and STAGES research combined. For example, a meta-analysis of over 350 empirical studies strongly supports the validity of the WUSCT assessment and the ego development model. Therefore, our argument for STAGES validity rests largely on WUSCT studies. Appendix 1 contains a short summary of the arguments and conclusions contained in the article, which can serve as an “executive summary” for the reader.

Background Context and Preface

In this preface I will explain what motivated me to write this paper—i.e. research and development in computer-based scoring—, which, other than in this Preface, is not a topic, discussed in the rest of the paper.

The assessment of ego development or meaning-making development has traditionally been labor-intensive and thus expensive, requiring highly trained individuals to score text from essay question responses, sentence completions, or transcribed structured interviews. This limits doing large-sample-sized studies, and limits its general availability to larger audiences who could benefit. Beyond research studies, the main practical application of these assessments has been in doing consulting and coaching work with professionals and small teams, where the cost of each assessment can be justified.

With recent progress in artificial intelligence, text analysis, and data science technologies it is possible to envision automated computer-based scoring of these assessments. In fact our group[1] has developed the first such technology, called the StageLens technology, which can assess sentence completion tests with limited accuracy. It is not yet accurate enough to provide results for individuals , but it is accurate enough for aggregate results for statistical conclusions in sufficiently large groups (of 20 or more individuals). This opens the door to doing large-scale studies, including random samples of populations and whole-organization assessments.[2]

Thus, the validity of the StageLens assessment rests in large part upon the validity of the STAGES model, which, in turn relies on the few validity studies of Cook-Greuter and Torbert’s SCT variations, which, in turn rely heavily upon the large body of work validating Loevinger’s WSUTC. Therefore, in this paper, in addition to giving readers an introduction to STAGES and ego/meaning-making development and measurement, we will step through the validity claims of each of these models.

Though our AI technology can be used to “learn” how to score based on examples from any large dataset of human-scored SCTs, StageLens has been trained with data scored using O’Fallon’s STAGES model. The MAP, LDP, and GLP SCTs developed by Cook-Greuter, Torbert, and their associates are relatively minor variations on Loevinger’s WUSCT test. O’Fallon’s STAGES model is a more significant departure within this lineage. There have been fewer validation studies done with STAGES.

The intended audience of this article includes those interested in using SCTs for practical purposes, yet who want to know the research and validity background that supports the SCT. A main use of the SCT assessment is in helping individuals reflect upon their challenges, goals, learning, and psychological/spiritual growth, usually through coaching or consultant sessions. In such situations the psychometric properties and statistical validity of the assessments has been de-emphasized (though still considered important). This is understandable because the whole of a person’s capacity cannot be reduced to a single number (a developmental level). Thus assessment results are usually used as a starting place for deep reflection, not for a definitive ranking or “high stakes” application. But as large-scale assessments become more feasible with automated scoring, attention once again turns to questions of psychometric validity and research methods.

This paper was originally drafted as a series of white papers to appear on the StageLens.com web site, to offer background information about the STAGES model and its predecessors to StageLens users. The occurrence of the STAGES Critique and Response articles in this issue of Integral Leadership Review has created an opportunity to publish that content more formally, as a published adjunct to the Response article. In the Response article (“A Response to Critiques of the STAGES Developmental Model”) readers will find explanations of additional nuances about STAGES that are not covered in this article.

An Introduction To Wisdom Skills and Adult Development

Why are wisdom skills important? A characteristic of modern culture is that we acknowledge that adults can psychologically change and grow over their lifespan—not just in storing new memories, learning new information, and being educated into new knowledge, but also in growing “developmentally” to change our most basic understandings of self, other, and world. It is a cliché that we live in a fast-changing, complex, and uncertain world, but we are only slowly coming to understand the capacities needed to craft wise decisions in the dynamic sea of diverse human activity and beliefs that we are thrown into in the 21st century. As Robert Kegan argues in In Over Our Heads (1994), the demands of contemporary society often outstrip the reasoning (and feeling) capacities of individuals making day-to-day decisions in home, civic, and work environments.

Three things become increasingly important in regards to these capacities—what we will also call “wisdom skills.” The first is determining the match between the demands of a task, decision, or role and an individual’s (or group’s) wisdom capacities—i.e. are the skills well matched to the demands of the context?[3] Second, assuming it is beneficial to do so, how do we support and strengthen any needed capacities? This article focuses on a third need that is a prerequisite to approaching the first two in realistic, practical, and systematic ways: we need to be able to assess these capacities to make good decisions about both matching and supporting them.

Our current research and development uses Terri O’Fallon’s STAGES model of adult development (O’Fallon, 2011, 2013). STAGES is an extension of the work of Susanne Cook-Greuter on post-autonomous levels of development (1999, 2002); which is, in turn, an extension of the large body of work related to Jane Loevinger’s model of “ego development” (later also called “leadership maturity” by Cook-Greuter and Torbert (2009)). In this introduction we aim to describe wisdom skill in terms of ego development and meaning-making development, and describe the basic principles of adult development for those new to the topic (including: vertical vs. horizontal growth, how levels transcend and include earlier levels, and what enables and supports development).

What is wisdom and how does it relate to meaning making? Most of us have an intuition about the types of capacities that we think demonstrate wisdom or psychosocial maturity in adults. But how do we precisely describe this intuition about human potential—what is in common among those whom we admire as wise?[4]

The focus of “21st Century” education and workforce development has been on skills such as: critical thinking; creativity, self-understanding, abstract reasoning, social/emotional/communication skills, curiosity and inquiry skills, understanding systems and wholes, and grounding ideas in pragmatic realities (AACU, 2007; NSTA, 2011; Clark et al., 2009; Pellegrino & Hilton, 2012; Scardamalia et al., 2012). A similar set of skills has been suggested for citizens to participate in a robust democracy (Muhlberger & Weber, 2006; Rosenberg, 2004, 2007).

Though these civic-participation and workforce-ready skills have a relatively pragmatic and cognitive focus, they overlap with the skills described in the sociological, philosophical, personality, and spiritual literature on “wisdom” per se (see Walsh, 2015; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Meeks & Jeste ,2009; Bangen et al. 2013; Fry & Wigglesworth, 2013). However, when we talk about the capacities that we expect in wise individuals (including leaders), additional skills come into play, including: multi-stakeholder perspective taking, robustness within paradox and uncertainty (“dialectical thinking”), empathy, humility and self-reflection. Wisdom skills (and meaning making maturity) involve the application of cognitive or reasoning capacities to the domains of human life (e.g. one’s relationship to the beliefs and preferences of self and other). We can roughly summarize wisdom skills with these capacities:[5]

- self-understanding, including self-reflection, self-awareness;

- seeing big pictures, including relational dynamics, contexts, and systems;

- perspective-taking, empathy, compassion, and an appreciation for the diversity of human values, abilities, and contexts;

- tolerance of and appreciation for uncertainty, paradox, and ambiguity;

- a humility that includes being aware of the fallibilities in one’s own beliefs and the limits of human reasoning in general; and

- sound pragmatic judgment that accounts for observable reality, i.e. a balanced appreciation for the actual and specific complexities of human nature and of physical reality on earth.

When we think about the significant challenges of home, work, or civic life, it seems that such wisdom skills are both essential and too often in short supply. To understand, research, or take leadership around complex societal dilemmas the assessment of wisdom skills is important. Important enough to try, even though the difficulties in assessing (and even defining) wisdom will guarantee imperfect methodologies and models.

The above description of wisdom skills implicates a large and complex set of capacities. These include cognitive (thinking) skills, affective (feeling) skills, personality traits, and values. However, to a first approximation, this set of skills can be successfully integrated into a single developmental construct, as has been done by Loevinger, Kegan, and others. These lines of research use what Loevinger calls “holist views of personality…[that] see behaviors in terms of meaning or purposes” (Loevinger 1970, p. 3). Kegan et al. (1998, p. 55) describe it as a “consistency in the structure, or order of complexity, of one’s meaning-making (i.e. how one thinks).” These lines of research argue that the diverse set of wisdom capacities are closely related to each other, influence each other, and, in a very rough sense, tend to grow together as people mature (statistically and in general, though they don’t necessarily track together with each individual). For example, Kegan et al. (p. 55) notes that Lahey (1986) found “an extraordinary degree of epistemological consistency within subjects across [the] domains” of intimate love relationships and more formal work relationships.

Robert Kegan and many others refer to this overarching capacity in terms of the complexity of one’s “meaning making”. Loevinger used the term “ego development.” We also use the term “wisdom skills.”[6] By any definition these sub-skills, and the overarching construct, exist on a developmental continuum that ranges from more concrete, simplistic, black/white, right/wrong, us/them, win/loose modes of meaning making to increasingly more flexible, reflective, complex, and nuanced modes. The vast majority of scholarship on thinking skills, whether it be in the academic areas (“silos”) of critical thinking, scientific reasoning, civic engagement, leadership and workforce readiness, wisdom studies, or personality traits, overlooks the developmental nature of these skills and does not cite the important research in adult developmental theory. Developmental models add key insights to the topic.

Adult development and learning is sometimes described in terms of general principles of change and growth without any measurable or specific levels,[7] but here we focus on a wide terrain of models that do use a sequence of specific and assessable levels.[8] It is beyond our scope here to describe the developmental levels proposed by Loevinger, Cook-Greuter, Kegan, and others, but we include some summaries in Appendix 3 to give a flavor of how these levels are described in the field. Scanning those descriptions will give the reader a concrete understanding to ground the abstract properties of development we describe next.

Manners (2001, p. 549) describes Loevinger’s theory as representing “an integration of diverse personality characteristics.” Loevinger describes ego development as being concerned with “impulse control and character development, with interpersonal relations, and with [conscious] preoccupations, including self-concept” (Loevinger 1970, p. 3); and she describes the function of ego as a “structure of expectations,” a “striving to master, to integrate, [and] to make sense of experience” (Loevinger, 1976, p. 59).

We can say that this holistic set of life-skills involves an increasingly mature and adequate understanding of the relationships among three realms: self, others, and the world (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cognitive in Kegan’s terms (1994); and “I/we/it” in terms of Wilber’s Integral Theory (1995)).

Development: vertical vs. horizontal growth. What do we mean by the “development” of these wisdom skills? Through experience, practice, and/or instruction people learn and grow their capacities, i.e. their skill and understanding. A rough distinction is made between horizontal and vertical learning. Horizontal learning involves learning more of the same thing—increased breadth, refinement, or differentiation of existing knowledge or skill. Development refers to vertical (hierarchical) learning, in which a qualitatively new level of capacity emerges from the coordination, re-organization, or integration of a diverse set of lower level building blocks. A child may learn each of these skills separately: running, catching a ball, throwing a ball, and what it means to coordinate movement with others. To improve in each skill involves horizontal learning. To integrate them into the skill of “playing baseball” is a vertical transformation to another order of complexity and integration. Another example of vertical learning is the coordination of the adult skills of helping, self-reliance, leadership, etc., into the complex skill of “parenting.”

The shape of development. According to developmental theories, learning within any domain progresses roughly as follows: (1) in the early phases of learning one struggles to make sense of (or perform, or maintain a focused awareness of) some new type of thing (a concept, behavior, skill, idea, etc.); (2) once the capacity to deal with individual things of that type stabilizes, horizontal acquisition can proceed, and more of that type of thing is understood; (3) within horizontal growth one also learns about relationships between the things; and the type and complexity of these relationships increases; (4) at some level of breadth and complexity something rather magical happens, and a new level of simplicity and elegance emerges, often in a spurt of reorganization; (5) This reorganization creates a new thing at a higher (or later) level and the process starts all over again as one struggles to make sense of this new type of thing (Kegan, 1994; Commons et al. 1998; Fischer 1980).

Also, the early stages of learning usually begin in an external, factual, or “declarative” form—for example when a mentor describes or shows how to swing a golf club, how to solve a quadratic equation, how to drive a car, or how to parent well—and then one practices performing these instructions. With practice one moves from declarative to “procedural” knowledge, the ability to perform a task without needing to think about its steps. It is a movement from “knowing that” to “knowing how” (see theories of cognition such as Anderson, 1983; Laird et. al, 1987). Eventually, with enough practice, the skill becomes fully automated and effortless, and one may even forget the declarative knowledge that one started with (for example, one might develop deep skill in golf, driving, or parenting, but not be very good at explaining what or how they are performing it).

The levels of stage-like growth form an invariant sequence—levels can not be skipped, any more than one can learn calculus without first learning algebra, since each level forms structured wholes based on, or as Wilber puts it “transcending and including,” the prior level(s). The term “simplexity” has been used to describe how an emergent higher level structure is both more complex, because it integrates lower level capacities and provides and adaptive response to more complex situations; and simpler, because of the transition from a complicated but chaotically organized skill set into a more elegant set of coordinated skills—an emergent skill at a new level.

Levels or stages of development. Stage theories of adult development propose discrete stages or levels mapping from early to late stages of maturity.[9] Theories differ on the number and granularity of levels, but a general concordance can be seen across all of them (Wilber, 2000; Stein & Heikkinen, 2009). Similar patterns of developmental progressions have been discovered in hundreds of studies across many areas, including ethics, values, perspective-taking, decision-making, epistemology (understanding the limits of knowledge), and spirituality (see Wilber, 2006). Most of these theories (beginning in the 1950’s) described the general trend in terms of “pre-conventional to conventional to post-conventional” levels of adult development, and then define refinements within that spectrum resulting in between 5 and 12 levels. More recent work such as Kegan, Cook-Greuter, and O’Fallon’s projects, have mapped out later stages, referred to as post-post-conventional, post-autonomous, trans-rational, post-formal, or dialectical (these are similar terms for the same territory, not a sequence of levels) (Pfaffenberger et al., 2011).

For example, Kegan’s model has five stages of mental complexity (qualitatively different “orders of mind”). It frames development in terms of successive stages of becoming aware of aspects of the self that we were not previously aware of, yet they influenced our beliefs and actions. That is to look at what we previously (unknowingly) were looking through—which he calls turning subject into object. For example, we can learn to notice and describe our emotions in addition to simply having them; we can move from being able to plan to be able to think and talk about how to make a good plan. Kegan’s (1994) In Over Our Heads eloquently charts how developmental maturation governs one’s approach to the main domains of life: relationships, work, learning, parenting, and communicating.

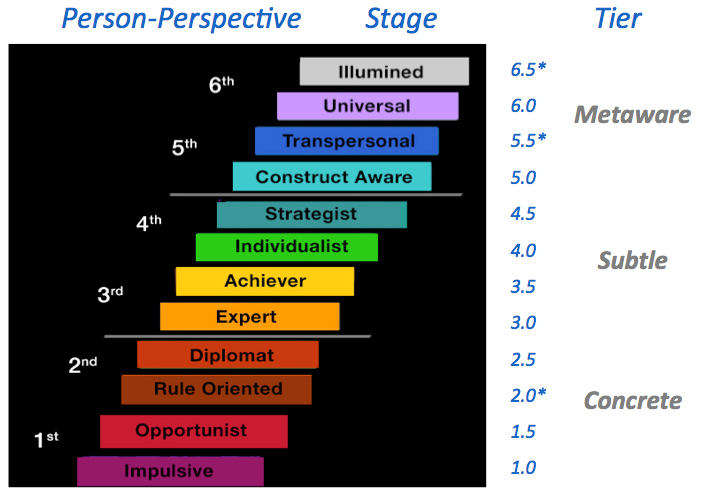

Torbert and Cook-Greuter’s model (based on Loevinger’s work) includes nine “action logic” levels of ego development or “leadership maturity,” where each level involves a more sophisticated way to structure and coordinate thoughts and decisions (Cook-Greuter, 2002; Rooke & Torbert, 2005). O’Fallon’s model, described later, includes 12 levels.

Cook-Greuter describes these action logics this way: “each meaning making system, world view, or stage is more comprehensive, more differentiated and more effective in dealing with the complexities of life than its predecessors…It describes increases in what we are aware of, or what we can pay attention to, and therefore what we can influence and integrate” (2004, p. 2,3). Thus, similar to Kegan’s theory, what is being described is what one is not so much what one can do as what one is aware of, can speak and reflect on, and, eventually, can try to investigate, manipulate or change. It is useful to remember that one can perform a skill or ability automatically or unconsciously, but that does not “count” in meaning-making development until it “becomes object.” For example, a child can implicitly make and follow a plan for how to get from their house, through the woods, to their friend’s house. A developmental step is marked when they can talk about that plan and what is the best way to go (at the concrete level); and a further developmental level (called the formal, abstract, or subtle level) is marked when they can talk about the planning process, as in What is the most efficient way to make a plan, and How can we compare and combine our plans?

Appendix 2 shows some correspondences between the levels defined in various theories. Appendix 3 shows several descriptions of developmental progressions through stages. To describe each level or compare different models is beyond our scope, but the reader will appreciate the significant similarities in how they describe increasing complexity and nuance of I/We/it interrelationships.

These stage progressions have been used to describe development from childhood through late adulthood, to describe important meaning-making differences among adults, and differences in leadership style. In addition some theories use similar level descriptions but focus on developmental or evolution of cultures or groups (such as organizational cultures and anthropological epochs) (Wilber, 2006; Beck & Cowan, 1996; Thompson, 2007). The ability to use the same concepts describing increasing levels of complexity and integration (across I/we/it domains) to discuss both individual and collective capacity has been a powerful theoretical explanatory tool (though we must note that theories relating to cultures and groups have far less empirical validation, and sometimes the transfer of developmental principles from individual to collective may be more metaphoric than direct).

What causes or supports development? Development occurs through a dynamic interactions between self and world. It is spurred when new contexts or information challenge a person’s existing beliefs, skills, or frames of reference. To avoid the uncomfortable dissonance of conflicting ideas, the meaning-making drive strives to either modify the new information to agree with the existing frame of reference (“assimilation”), or modify the meaning-making frame to harmonize with the new information (“adaptation,” and see Kegan, 1982). The greater complexity and greater simplicity of a new developmental level comes from its ability to find a higher perspective in which ideas (or skills) A and B, which seemed previously contradictory or disjointed, can meaningfully and productively co-exist.

It is widely noted that, as Kegan put it “people grow best where they continuously experience an ingenious blend of support and challenge” (1994, p. 42). The concept was originally articulated as the “zone of proximal development” by Vygotsky, 1978 and O’Fallon and Fitch speak of development spurned by “disorienting dilemmas.” Across different life contexts an individual can display a range of developmental levels. King & Kitchener (2004, p. 9) state that “variability in individuals’ responses across tasks reflects the degree of ‘contextual support’ available at the time (e.g., memory prompts, feedback, opportunity to practice).” Tasks that require performance without support elicit a person’s “functional level” capacity, while tasks that provide contextual support can elicit performance at an “optimal level” that is closer to the upper limit of the person’s cognitive capacity.[10]

Vertical development is both very gradual and not guaranteed, especially beyond conventional levels, as the cultural surround tends to resist ideation that threatens the status quo. It is generally thought that it takes 3-5 years to grow one level, if conditions are right. Loevinger (1979, p. 303) noted that “attempts to raise ego level experimentally in a few weeks have not succeeded, but experiments that have lasted 6 to 9 months have had statistically significant success [on average a fraction of a level]. [And] people can lower their score more reliably and decisively than they can raise it.” Cook-Greuter (1999, p. 52) says that we can “only conclude that an individual performs at least at such and such a stage under the test conditions, but one cannot exclude the possibility that they might operate at a higher level if given support… probed for further explanations and meaning…or given altered test instructions”.

A detailed discussion of what is thought to support wisdom skill development is beyond our scope here, but processes hypothesized to support development include (and see Wilber et al., 2008):

- contemplative and reflective practices,

- social opportunities for feedback and reflection,

- targeted deep psychological or psychoanalytic work, such as “shadow work,”

- participating in social contexts where diverse perspectives are represented and discussed,

- associating with individuals or community at later developmental levels, and

- learning new models or concepts that embrace and integrate seemingly contradictory ideas.

Again, it is important to note that these are the things believed to support development, in part from anecdotal evidence but also from empirical studies about what works on average. But that there are many unknowns and contextual factors involved, and there is no evidence that these things will guarantee growth for any individual.

To continue reviewing the evidence, Vincent (2013) notes that “personality characteristics may enhance or constrain ego development” and in particular ego development has been found to correlate somewhat with Openness on the Big-5 Personality Inventory, and that “a preference for Intuition on the MBTI was associated with significantly higher ego development on program entry and with greater ego development during the programs” (p. 197).

Pfaffenberger (2005, p. 290) summarizes studies suggesting that the challenge of a difficult situation is not enough to spur growth, but that “accommodation [i.e. growth] was not related to the experience of difficulty per se but to seeing it as challenging one’s worldview and to consciously struggling with the event…[and]…therapy may promote development exactly because the conscious engagement in life problems seems to be what facilitates growth and therapy often engages this kind of process.” King (2011) describes evidence that development is not simply a result of dealing with life challenges, but that growth also requires an attitude of active and reflective engagement with those challenges.

Torbert (1994) describes a study of introducing an “action inquiry” approach to managerial training. It emphasizes deep reflection into the relationships between meaning-making and action within the I/we/it spheres. This led to notable increases in outcome developmental levels (though the sample size was small). Alexander et al. (1994) conducted a longitudinal study showing that graduates of a college emphasizing meditation and spiritual philosophy resulted in significant gains in ego development vs. comparative liberal arts and engineering colleges.

In a study by Vincent et al. (2015) evaluating an “enhanced” community leadership development (CLP) program that included additional psychosocial challenges such as experiences that are interpersonal, emotionally engaging, personally salient and structurally disequilibriating, found that for later conventional consciousness stages “enhanced CLPs were significantly more successful in triggering post-conventional development” (238).

Though the above is about the development of individuals, many authors have proposed similar developmental progressions for the evolution of culture (Wilber, 2007; Harari, 2014; Rifkin, 2009; Diamond, 1998; Thompson, 1998). Developmental advances in societies can lead not only to new understandings, but to new technologies and new social structures (and vice versa, in what Wilber calls “tetra-enaction”). Each later structure (social or cognitive), while solving some problems, will inevitably introduce new dilemmas. For example, the inventions of fire, shelter, money, and computers—all solved one set of problems while creating other problems. If conditions are right, over time this can create a spiral of ever-increasing development and complexity in culture and society.

Note that developmental progress is in no way guaranteed. People and cultures can respond to dilemmas by ignoring what does not fit the current frame, or even regress to developmentally prior modes of response to avoid dissonance or perceived threat. Sometimes, in situations of threat or calamity, it is completely appropriate to “down shift” to earlier, more black-and-white or quick-and-dirty, modes of reason and action.

Caveats and Concerns. We end this brief introduction to adult development with some caveats. Clearly the developmental perspective is powerful, both in its potential to help us make sense of the human condition, and (as we show later) in its scientifically validated ability to predict certain human characteristics. But it is important to note that the more powerful a theory is, the more susceptible it is to misunderstanding, over-generalization, and misuse. Fleshing out all of the caveats is beyond our scope here (see Stein, 2008; Murray, 2011), but here are some important caveats:

(1) Though the models describe general patterns, it is important not to pigeon-hole individuals into caricatures—individual differences are as profound as the general trends. One’s developmental level probably has something to say about how one approaches parenting, relationships, work, learning, etc., but does not predict exactly how any individual will think or act in any context.

(2) Though we might speak of someone’s “center of gravity” as their most common meaning-making level, people embody a range of levels at different times, depending on the challenges and supports present in any context.

(3) “Higher” (later stage) development is not always needed or useful. If an individual is thriving adequately within their context, why push development? (In fact, doing so can be harmful.)

(4) Though we focus on the broad holistic capacity of “meaning making” that generally coordinates over many developmental lines and life contexts, each line or context can develop at different rates. This not only argues against pigeon-holing (#1) but makes the point that moral/ethical or spiritual development can lag behind ego or cognitive development. One can develop very sophisticated meaning-making capacities relating self-other-and-world, and still be malicious, narcissistic, or otherwise socially deviant.[11]

(5) Healthy horizontal development at each level is (arguably) more important than vertical development. Each level builds upon prior levels, and weaknesses or pathologies can exist in foundational layers of the psyche. In other words, the “shadow work” of cleaning up earlier levels of development is usually more important to the overall health of self and the world than pushing for vertical development.[12]

Sometimes the most important things in life are the most difficult to measure or assess, but that should not obstruct our inquiring. For example, NGOs and even some countries are increasingly interesting in measuring constructs like “gross national happiness,” or environmental health—difficult but noble and important goals. Similarly, we will find that the development of wisdom or meaning making maturity is difficult to define and measure, but this difficulty has not prevented significant research into the issue. Likewise, the many caveats and limitations involved with putting the theory and measurement of “wisdom skills” to use should not deter our inquiry, but motivate a diligence in method and ethics.

Defining and Measuring Ego Development

In the Introduction we described “wisdom skill(s)” and the related constructs of ego-development and meaning-making maturity to illustrate the importance and nature of these constructs for those new to the topic. Here we will focus in on Loevinger’s concept of ego development—exploring the definition and range of the construct from an academic, research, and validity perspective.

We can put the work of Loevinger and her successors into the larger context of constructive-developmental models. Jane Loevinger’s (1966) theory of ego development and Robert Kegan’s theory of meaning-making development (1994) have substantial overlap, as noted in prior sections. However, they use different measurement methods, with Loevinger using a “semi-projective” sentence completion test and Kegan using a structured interview method.[13] Both are quite labor-intensive to score as compared with psychological tests that use multiple-choice or fixed-answer methods, and in return, the more complex methods are thought to yield deeper and more valid results than the self-rated fixed-choice methods. The interview method is particularly labor-intensive—both to take/administer, and to score. In discussing the measurement of meaning-making in this section we focus on the sentence completion tests (SCTs) of Loevinger and colleagues, while above we have also drawn conceptually from Kegan’s theory. Newman et al. (1998, p. 985) noted that,

Ego development is one of the most comprehensive trait constructs in personality psychology. It has been described as a ‘master trait’ (Blasi, 1976; Loevinger, 1966) in that it serves as a schematic frame of reference providing a meaningful organization for numerous more specific personality traits. The detailed conception, as formulated by Jane Loevinger (1976), represents both a developmental characterology or scale of psychological maturation beginning in childhood and a major source of individual differences in adult personality organization.

Browning (1987, p 113) notes that the ego development “[postulates] a series of developmental stages that are assumed to form a hierarchical continuum and to occur in an invariant sequence…[describing a] person’s customary organizing frame of reference, which involves, in the course of development, an increasingly complex synthesis of impulse control, conscious preoccupations, cognitive complexity, and interpersonal style.”

The above descriptions are characteristic of Kegan’s theory as well—next we move specifically to the SCT and the WUSCT. Below is a description of ego development levels that includes insights from Cook-Greuter and Torbert (more descriptions of levels can be found in Appendix 2, 3).

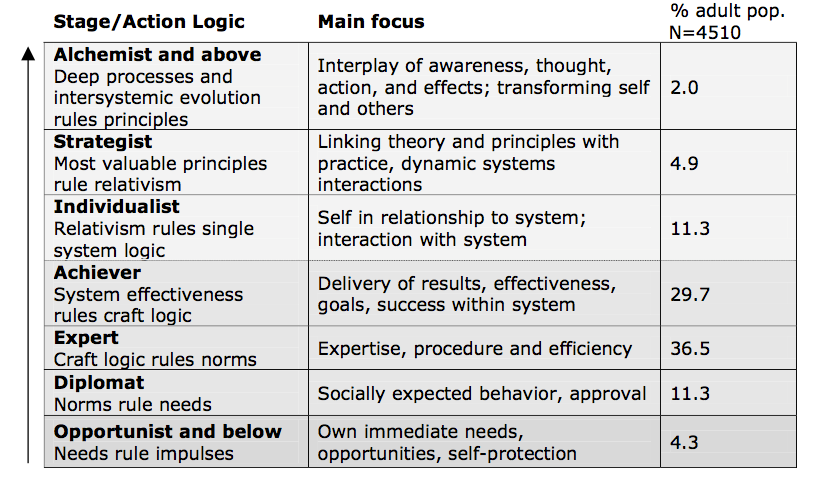

Table 1: Ego Development Stages (Cook-Greuter, 2004, p. 279)

Ego development and the WUSCT. Jane Loevinger developed and refined the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT) over several decades as a tool to measure what she eventually called “ego development.” The WUSCT is a 36-item sentence completion test. The items of the WUSCT address a variety of issues, including how respondents perceive and respond to personal relationships (e.g., ‘My mother and I…’), authority (e.g., ‘Rules are…’), frustration (e.g., ‘If I can’t get what I want…’), and everyday issues (e.g., ‘Raising a family…’). Loevinger’s approach was primarily data-driven, in that the theory or model of development grew out of analysis of large amounts of assessment data, in contrast to frameworks that start with a theory and develop assessments from there. In addition, scoring the assessment is exemplar-based—i.e. the scoring instructions contain thousands of categorized (actual) sentence completions, rather than descriptions of conceptual or syntactic properties of the completion text.

A distinctive aspect of the WUSCT is that it is a projective (or semi-projective) instrument, as is the Rorschach Inkblot test or any free-association task. This contrasts with other types of psychological and cognitive assessments including multiple-choice self-rating surveys (or sorting or peer-rating instruments), structured interview methods, reflective problem- or dilemma-solving tasks, and behavioral assessments. In projective tests subjects are not asked to produce a good or correct answer (the instruction are simply “complete the following sentences”). Rather, respondents freely “project” their frame of reference, world-view, assumptions, etc. into their answers. Though the Rorschach test has come under scrutiny, Lilienfeld et al. (2000, p. 56) note that the WUSCT “is arguably the most extensively validated projective technique.”

On multiple intelligences. Next we address the complexity of the concept of “ego development” itself. Is it really one thing—a clear “developmental line,” or is it a combination of clearly identifiable components? Is it too vague or general to be defined and measured? First, we discuss what it means to delineate a discrete type or “line” of human capacity.

Gardner developed the concept of “multiple intelligences” (1983) which Wilber refined in his description of separate “developmental lines,” including cognitive, ego (self-sense), values, morals, needs, faith/spirituality, emotional, and kinesthetic lines (2006). Though this model serves well as a first pass in trying to integrate many threads of psychological and developmental research, when one tries to apply it, it quickly becomes apparent that these categories are massively overlapping with each other (e.g. spiritual, ego, and social-emotional skills have much overlap).

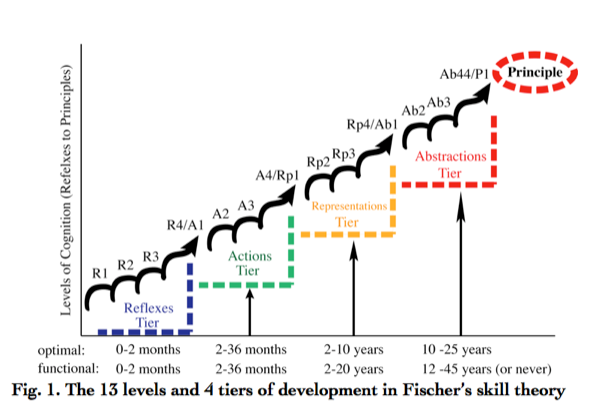

Kurt Fisher’s Skill Theory (1980) provides important insights into this issue (as does Hierarchical Complexity Theory (HCT), a similar theory by Michael Commons, Commons et al., 1989). Fischer claims that skills develop in response to the demands of real life task situations: “the skill level that a person displays…cannot be considered independently of the context in which that skill is assessed” (Fischer & Farrar, 1987, p. 646). Athletic skill, parenting skill, arithmetic skill, and musical skill are largely independent because the task situations in which we learn and use these skills usually have little overlap. At a more fundamental level, very basic human skills and emotional drives such as those dealing with reproduction, eating, and territory, seem to operate fairly independently because the task situations or life-needs they address are relatively independent.

But complex human social contexts such as communication, decision making, parenting, leadership, and learning have massively overlapping domains and characteristics, so the skills developed to meet these needs must be expected to be equally overlapping and difficult to separate. So, even though Skill Theory (and HCT) is used to create precise definitions of human skills so that they can be studied independently, Skill Theory can also be used to explain why it is so problematic to separate complex human capacities like ego-development, parenting, communicating, leadership, or self-understanding into separate well-defined developmental “lines.” And it supports the validity of using a wide and harder-to-define construct like ego-development or meaning-making maturity.

On can note a similar phenomena within the domain of cognitive research on “higher order thinking skills,” where one sees a plethora of constructs being studied: metacognition, reflective judgment, scientific inquiry skills, critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, etc. Wisdom (mature meaning making) seems to be related to all of these in some way. Though there is great value in studying each of these in isolation, once again we face the fact that there is massive overlap in how they are defined and understood. Deanne Kuhn’s significant body of research illustrates the deep interconnections among all of these skill sets, and she discusses the definitional and methodological conundrums of teasing them apart as separate skills (Kuhn et al, 1999, 2000, 2008).[14] Skill Theory explains why they are difficult to separate (though, again, for some types of applications it is quite appropriate to do so).

Cognitive vs. emotional skill. The so-called “higher order skills” are primarily reasoning skills, while ego development and related adult developmental models clearly also imply emotional/social skills. The most prominent or general categorization of human capacities is reason (thinking or cognitive) vs. affect (emotional or socio-emotional). But even this basic categorization is extremely problematic, both conceptually, because all real-world reasoning includes affective aspects, and scientifically, as brain science has discovered the deep interconnectivity of the higher and lower brain centers (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007; Goleman, 1995).

It is self-evident that people can have very strong intellectual skills while having deplorable socio-emotional skills. Brain science and evolutionary biology clearly indicate that (basic) emotional processes are distinct from reasoning processes, while, as mentioned, also showing that they strongly influence each other. Rather than frame intellectual vs. socio-emotional skills as disjoint sibling capacities, we have found it best to describe wisdom skill as involving the application of higher order intellectual skills (judgment, metacognition, critical thinking, etc.) to the domains of self and other (I, you, we, us, them, etc.). Intellectual skills by themselves are understood to apply to the domain of “it” or outside objects, but these skills can be applied to, not some idea, but my/your/our/their ideas (or needs, values, etc.). This helps explain the intuition that a certain level of complexity in the “cognitive line” in some way precedes or is a prerequisite for ego development (wisdom skill).[15]

One skill-set to rule them all? Kegan and Loevinger are among those researchers who see ego or meaning making as an overarching and unitary trait. According to Jespersen et al. (2013, p. 229):

Loevinger’s life’s work has been devoted to charting the course of ego development through a series of predictable, hierarchically organized stages from early childhood through adult life…[The ego], for Loevinger (1976), is a ‘master trait’ of personality…a holistic process, a striving for meaning and self-consistency over time…[it] involves many dimensions of personality development, such as motives for behavior, moral reasoning, and cognitive complexity, as well as ways of understanding oneself and others…[the ego is implicated] in activities such as impulse control, cognitive functioning, interpersonal relationship style, and conscious preoccupations…

Theorists disagree on whether ego is actually a single master trait or is composed of an interlocking set of sub-traits that act as one factor. This nuance is unimportant for our current purposes. Numerous studies have used statistical methods (including homogeneity, factor, cluster analyses) to show that the ego development construct measured by the WUSCT “loads on a single factor,” i.e. appears to be mainly measuring one and only one construct (Westenberg et al. 2004a, p. 606).[16] In sum, several lines of reasoning can be used to support the validity of ego development (or meaning-making or wisdom skill as we use the terms) as a valid unified construct.

Cook-Greuter’s study of Post-autonomous levels, and person-perspectives. Susanne Cook-Greater extended Loevinger’s work by more closely mapping out the terrain of the later level, ‘post-autonomous’ or ‘post-formal,’ stages (1999, 2002). Loevinger’s theory was based on a wide variety of populations, including pregnant mothers, prisoners, college students, etc., and is strongest in its descriptions of the most common stages. Cook-Greuter was interested in the characteristics of later stages of maturity, which one might assume are more prevalent among professionals, leaders, the college-educated, and perhaps even spiritual seekers. In her ground-breaking dissertation work she evaluated thousands of WUSCT surveys collected in prior studies, and from that drew out and re-analyzed data on the later stages.

Cook-Greuter refined the definitions and scoring procedures for the later stages, and added an additional level to Loevinger’s model. Following this she continued her research while making a move that Loevinger was critical of: using the sentence completion instrument to score individuals and give them coaching or consultation (as opposed to restricting its use to research applications). Cook-Greuter, along with Bill Torbert, refined the theory and method further over years of field experience. This included the opportunity to collect data on many more late-stage individuals. Modifications of the WUSCT were created (see Torbert 2014 for a comparison of Cook-Greuter’s MAP, and variations called GLP and LDP, which all share 80% of the same stems with the WUSCT). Some sentence stems were changed to better fit the needs of business leadership or personal-growth contexts. Scoring manuals were extended and refined. The business of developmental scoring became a business, expanding the potential for the developmental perspective to benefit society, while also taking on the risks and concerns implied in commercializing the results of an academic project.

Though Loevinger was not explicitly trying to focus on any part of the developmental progression, she was, through constraint of the data gathered, or from implicit preferences, focused more on the conventional and early postconventional levels. Loevinger’s theory focused on changes in impulse control, goal orientation, interpersonal relations, and conscious preoccupations, and these (particularly the first two) changes characterize growth from pre-conventional to conventional to early post-conventional stages. Appendix 3 contains a number of comparable description systems for developmental levels that will give the reader a feel for them. Describing them in detail is beyond our scope, but in describing Cook-Greuter’s contributions we will give a bit more detail about the later levels that she mapped out.

In later stages, as one gains some freedom from, or at least perspective on, one’s own cultural conditioning, the focus of the transitions is different. Cook-Greuter (1999, p. 3):

Conventional stages describe forms of meaning making that seem required for adults to function in the roles of modem societies. Postconventional ego development, on the other hand, describes the rarer stages of meaning making in which some adults begin to deliberately and consciously wrestle with culturally programmed responses to life. They begin to examine previously taken-for-granted assumptions and explore the fundamental questions about knowing and reality.

Prior theories told a developmental story of increasing competence, autonomy, and social awareness with increasing development. Cook-Greuter did not refute this pattern, but discovered that for the later stages there is a deconstructive move as well, in which the limitations of knowledge and the ambiguity of the self-system become apparent. Her description of later stages of development includes:

The ego becomes transparent to itself; [one] looks at all experience fully in terms of change and evolution [and one becomes] aware of the ego’s clever and vigilant machinations at self-preservation…[One becomes] cognizant of the pitfalls of the language habit [and starts] to realize the absurdity [or] limits of human map making….[one remains] aware of the pseudo-reality created by words…[and becomes] aware of the profound splits and paradoxes inherent in rational thought…Good and evil, life and death, beauty and ugliness may now appear as two sides of the same coin, as mutually necessitating and defining each other. (Cook-Greuter, 2000, p. 21-30).

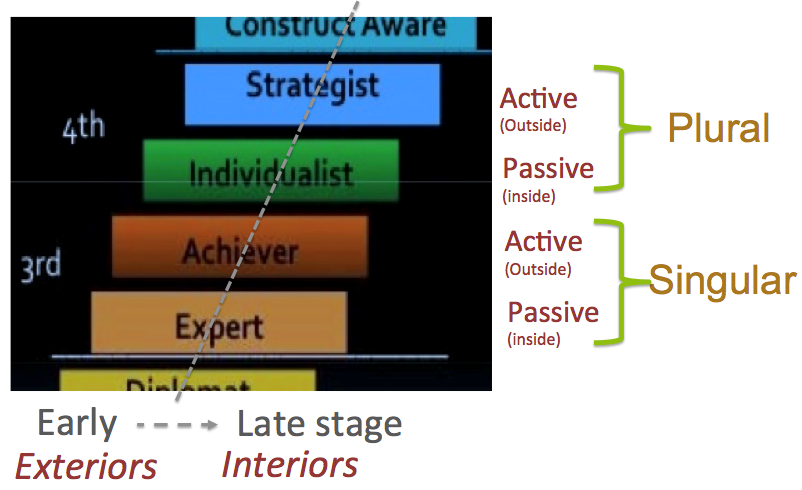

Another key insight from Cook-Greuter was to frame developmental progression in terms of “person perspectives.” Scholars have noted how children’s cognitive development increases in complexity by moving from first to second to third-person perspectives. The second person perspective is the ability to imagine or acknowledge the perspectives of others, as is required to move from narcissistic self-interest of the toddler into the adult world of social conventions. Third person perspective is the ability to imagine what any reasonable person would think, i.e. being able to reason “objectively,” as is required in the modern world of scientific thought and democratic deliberation. Cook-Greuter discovered that this framework could be extended into fourth and fifth person perspectives (and, theoretically, further) as a unifying frame for ego development. This roughly parallels Kegan’s hierarchical subject-to-object progression, as each level can “see” and think about the prior one as an object of reason.

Thus, though development through earlier action logics usher in changes in traits like impulse control and goal orientations, later stages are accompanied by changes including openness to ambiguity and dissonance. Barker & Torbert (2011, p. 55) report on Nicolaides (2008) study: “unlike people at conventional action logics who tend to try to avoid ambiguity, all of her post conventional sample saw positive, creative potential in ambiguity. But within this broad similarity, she found for distinctive responses to ambiguity: the Individualist, Stage 7, endured it; the Strategist, Stage 8, tolerated it; the Alchemists, Stage 9, surrendered to it, and the Ironist, Stage 10, generated it.

Total protocol scores. Before moving to the section on the validity of the SCT, we should describe one technical detail about how the test is interpreted. In scoring a sentence completion protocol each item is given a score, independently of the rest of the items, and then the 36 scores are summarized into an overall score. Loevinger and others are most interested in determining a “center of gravity” score, or Total Protocol Rating (TPR) and are less concerned about the nuances and contour of levels across all 36 items.[17]

Deciding how to calculate this overall score turns out to be a complex question. One reason is that participants are expected to exhibit a range of developmental levels in their answers. In a projective test the subject is not trying to score as high as she can, and it is actually seen as more healthy or well-rounded when responses range over at least 3 or 4 levels (for individuals of low developmental levels there is less room to range over). Taking the average over 36 stems does not work. Our intuitive understanding of development tells us that if someone attains a score of, say, Strategist level, on 8 of the 36 items, then they must have a strategist level of meaning-making, because, according to both the theory and empirical evidence, it is difficult to “fake” or “guess” these items to produce a score higher than your actual level. Whether that individual has 5 or 15 scores at lower levels should not affect the center of gravity score. But having more low than mid-level scores does strongly affect an average over all stems.

The same limitation exists for taking a sum of the items, or using the mode. None of these methods match our intuition about the construct. (And, disconcerting as it may be, as explained elsewhere, in the end it is a shared intuition that grounds the meaning of the construct.) One way to compensate for this is using a weighted sum (or average) that gives higher scores more weight.

In fact, two separate methods are used to calculate overall protocol score. The Total Weighted Score (TWS) is just that, a sum over the items giving higher weights to higher scores. But the more often used method is the ogive method for arriving at a TPR, which assigns cutoffs for each level. The ogive formula is not a mathematical expression (as is the TWS) but a classification procedure that goes something like this: if there are at least 4 scores at level E or higher, score it at E; if there are at least 6 scores at level D or higher, score it at D… and so on from the highest score to the lowest (it is more complicated but this description suffices here). The ogive produces 8-12 (depending on the model) discrete levels and is thought to best match our intuitions about “levels of development.” The TWS produces an integer value ranging usually from about 100-400, and this continuous metric is preferable for some types of research studies. Holt et al. describe Loevinger’s reasoning this way: “Human development has this odd, psychometrically inconvenient property of maintaining the potentiality to respond on many lower levels after one has, in a certain sense, left them behind. The ogive rules respect this peculiarity and allow for it” (Holt et al., 1980, p. 917).

But how does one determine the exact cutoffs for the ogive method (or the weights for the TWS method)? For the ogive method Loevinger used probability theory (Bayes Theorem, Lee, 2012) to estimate how much evidence was needed to conclude that person was at a given level.[18] Though various statistical and comparative methods can be used to support the validity of any set of choices, each method depends on an ad-hoc choice of parameters (such as false positive rates or weights) and in the end the choices are uncomfortably and unavoidably arbitrary and linked to intuition—and there is no single “correct” right way to determine the cutoffs (or weights). Arguments are made in the literature, described in later sections, that the overall method, including the cutoffs used, has excellent validity. Though we cannot say for sure that some other method of aggregating the 36 items might be just as valid.[19]

Loevinger (1998, p. 5) describes the early process of defining the levels: “because we initially had no scoring manual, we discussed as a group how to classify each completion, trying to imagine the type of person who would give such a response” (emphasis mine). This lead to the first of a series of scoring manuals, all of them exemplar-based, i.e. a completion is scored by matching it to a set of real examples (which, in later manuals, are grouped into categories based on thematic similarity). To train to be a scorer is to learn to assimilate the intuitions embedded in the manual’s exemplar organization.

As could be expected, differences between (trained) scorers tend to average out, and scorers were “more confident on judging the ego level of a total protocol than that of a single response out of context” (IBID, p. 5). Westenberg et al. (2004a, p. 485) notes “the scoring manual for the SCT [32-item youth version] consists of over 2000 response categories…about 80 response categories for each of the 32 items.” The scoring manual used by Cook-Greuter, Torbert, and associates is over 300 pages long, with one chapter of examples for each of the 36 stems, with, usually, dozens of examples in each category. Training to use the manual takes many months and close supervision, until acceptable inter-rater reliability is achieved vs. other experts. Because human language is so diverse and expressive, i.e. because there are so many ways that an individual at level X could respond to stem Y, the creation of the example-based scoring manual requires the analysis of hundreds or even thousands of scored protocols.

Internal Validity of SCTs

In this section we will summarize the literature on the validity of Loevinger’s WUSCT and Cook-Greuter and Torbert’s modifications to it (the MAP, LDP, and GLP).[20] The literature drawing on Loevinger’s model is so extensive that it includes a number of meta-analysis and critical overviews, substantially supporting its validity and usefulness (Cohn & Westenberg, 2004; Manners & Durkin, 2001; Holt, 1980; Novy & Francis, 1992; Jespersen et al. 2013; Westenberg et al., 200b).

For psychological assessments the “method” includes the data collection instrument, in our case the SCT, and the data interpretation, in our case the scoring method. The instrument includes the instructions given, and the scoring method includes the scoring manual and the method used to train the scorers. Changes to any of these can affect the validity of the overall method. In what follows when we speak of the validity of the WUSCT we are including all of these things, though we mainly focus on the SCT itself.

For our purposes, validity judgments exist in two broad categories: internal and external validity.[21] Internal validity describes the quality, reliability, and repeatability of the assessment instrument or procedure itself, regardless of whether it is measuring anything useful, genuine, or meaningful. External validity describes how well a measurement instrument or experimental conclusion matches what it is supposed to measure or test. Are its results relevant and accurate across general real-world contexts—i.e. is it genuine and useful? For example, a weighing scale that is 10 lbs. too high has internal validity, in that you get consistent results from it, but it does not have external validity—it does not accurately measure what it is expected to measure.

Validity metrics are what compensate for the uncomfortable truth that psychological assessments are trying to measure something unobservable, vague and intuitive. An assessment with internal validity is a sound measurement of something, regardless whether it measures exactly what we intend. Strong external validity metrics support a claim that what is measured matches our intuitive or conceptual understanding of the construct.[22]

First we will discuss internal validity in terms of: inter-rater reliability, internal consistence, and test-retest reliability; and then external validity, including face validity, construct, and predictive validity.

Inter-rater reliability. Analyzing text or other qualitative data to derive a categorization or quantitative score is complex and uncertain business, usually requiring human judgment. Researchers compensate for the variability and subjectivity of human scoring by using multiple raters and measuring their agreement. A method is more objective and valid if raters tend to come to the same conclusion, and is less valid and too subjective if raters come to different conclusions. In the WUSCT literature several methods are used for assessing inter-rater reliability (IRR, agreement, or concordance), including percent agreement, Cohen’s’ kappa value, and correlations (usually Pearson’s R).[23] Below we summarize those results without getting into the nuances of these different methods.

Westenberg et al. report that “psychometric studies of the WUSCT…invariably report high levels of interrater reliability. Perfect interrater agreement per item averages about 85% and interrater agreement within one stage (i.e., disagreement not larger than one stage) is often close to 95%” (2004a, p. 603). Cohen’s Kappa values have been reported at about .80, which is considered excellent.[24]

Those statistics were for agreement at the level of the total protocol rating. For agreement at the level of each stem completion, Loevinger & Wesler (1970, p. 41) report agreements averaging 77% (ranging 60% to 86% over the stems); and correlations averaging .75. Pfaffenberger (2011, p. 11) says the literature generally points to higher IRRs (near .90). Newman et al. (1998) report a per item weighted kappa statistic averaging .73 (ranging .47 to .93).[25]

Internal consistency. Internal consistency measures the correlation between items on a test. It should be fairly high to indicate that all of the items are measuring essentially the same thing. However, for a test like the SCT, it is not expected to be too high because each sentence represents a different contextual perspective, and we expect individual differences in which contexts will reveal evidence about each person’s highest capacity (like triangulating a measurement from different angles). According to Westenberg et al. (2004b, p .693) “The WUSCT [displays] high internal consistency: Most studies report a Cronbach’s alpha of .90 or higher” (e.g., see Loevinger, 1998; Novy & Francis, 1992; Minard, 2000; Newman et al., 1998).[26]

Test-retest reliability. In general reliability refers to the extent to which repeated measurements yield consistent results. Test-retest reliability refers to whether an assessment measures a stable construct or something that varies due to uncontrollable or random factors. It also measures how taking a test again, by itself, influences the outcome. Meaning-making development is expected to change very slowly (some have estimated at least three years per level when conditions are supportive), though theoretically it can change fairly quickly when it does change, if the growth is in spurts.

The SCT assesses capacity at a moment in time, and it is possible that an individual is not “on top of their game” on that particular day and time.[27] Also, as Loevinger puts it: “frequent measurement is likely to be resented and hence to result in poor validity for retests” (1979, p. 287).[28] It is also possible that people can actually regress in their ego development, especially under periods of distress. Loevinger notes that “people can lower their score more reliably and decisively than they can raise it” (p. 303).

True test-retest assessments of the SCT, i.e. test of the stability and repeatability of results over short periods of time, are rare in the literature (perhaps because they are inconvenient for the test taker and time-consuming for the researcher) and most “retest” situations are longitudinal studies looking for growth over time. However, Westenberg et. al. (2004b, p. 603) report that the “test-retest reliability of the WUSCT [is] high, and test-retest correlations are often about .80.” Manners & Durkin (2011, p 545) say “in terms of test–retest reliability, when sufficient time is allowed between the two tests to allow for motivational effects, significant correlations have been found between test and retest scores.”

Faking, guessing, and scaffolding the SCT. A related issue is whether the SCT can be faked, gamed, or studied for. The anecdotal lore in the practice community is that it is quite difficult for a person to score much higher than their “actual” capacity, which is the case with any valid assessment of a skill that grows hierarchically (e.g. one normally can’t pretend to play the violin at a higher level than they are actually at). However, because SCTs are mediated by linguistic skill, one must have at least an adequate ability to articulate what one thinks or believes to have the score reflect their developmental level. Also, one can theoretically do better on the test by knowing how the test is scored and adjusting one’s language accordingly. This is one reason why scoring manuals are often kept confidential (and those using SCTs in for-profit coaching and consulting ventures of course have additional incentives to keep scoring methods proprietary).

As mentioned above, psychologists differentiate between functional (or characteristic) vs. optimal (ideal) performance, where the former represents everyday or average cognition and the latter represents the maximum capacity possible within ideal or well-supported contexts. Projective assessments like the SCT, in which the subject is not asked to give a “correct” answer, tend to elicit functional performance, but also can show a relatively wide range of levels over the items. Structured interview assessments, where interviewers probe for deeper reasoning, tend to elicit more optimal behavior (Kegan et al., 1998). Problem-solving or dilemma-reflection activities elicit behavior that is in between those extremes, since participants are presumably trying to do their best at something. Multiple-choice assessments often expected to rate later than the other types, since they rely on recognition rather than recall or construction of knowledge (and self-rating fixed-choice questions can be biased toward higher results as well).[29]

The instructions and context of the SCT can influence the outcome, especially if they provide any sort of support, “scaffolding,” or prompting. Westenberg et al. (2004) studied the SCT’s sensitivity to changes in the administration of the instrument. They found no significant difference between oral vs. written versions, and a very slight decrease in scores when it was administered orally via a telephone conversation. On changing the SCT instructions from simply “please complete the following sentences” to include instructions like “be candid” or “make a good impression,” they conclude that “several studies suggest that such instructions do not appear to influence ego level ratings” (p. 694). In contrast, “three other types of instructions, each with conceptual relevance to ego level, had a modest but significant impact” (IBID). The additional instructions included things like answering “…in the most complex and thought- provoking way,” and “…in as adult and mature a manner [as you can]…” In another study subjects were “provided with brief descriptions of each ego stage and instructed to complete the sentence stems as they would be completed by a person at the highest ego levels.” For all of these methods Westenberg et al. conclude that the “average increase was no more than one half a stage.”

All of the above suggests that the SCT can be influenced by various factors, but the variations caused by these factors are not more than a half a stage. However, even though there was a study where subjects were given a description of developmental levels, there is no study we are aware of that addresses how much a deeper instruction about development theory influences scores. This is an important question since many integrally-informed or developmentally-informed education/training/personal-growth programs employ developmental assessments, and use them to test the hypothesis that the program or intervention supports adult development. Loevinger (2011, p. 70) notes that contemporary subjects “are more sophisticated and educated in developmental theory than prior generations…[such that]..trying to prove to oneself that one is at a later stage is another hazard [in scoring, and] to distinguish between genuinely mature integrated protocols and those that consciously or unconsciously try to game the test has become a feeling aspect of training certified scores.”

More research is needed to know whether an observed change is truly from a deep transformation in meaning-making development or from a mere intellectual understanding and inculcation into a community valuing certain linguistic markers (or indeed, how to define the difference between those two things).

Variations in the length of the WUSCT. We have mentioned that there are various versions of the WUSCT and its successors. These variations involve new stem choices and/or using less that the standard 36 number of items. Some studies use a “split-half” version of the test, giving 18 of the stems as a pre-test and the other 18 as a post test or alternate test. Some variations of the SCT are targeted toward men, women, or youth. Our goal here is not to compare these variations in any detail, but to argue for the robustness of the SCT over such modifications.

As to the length of the SCT: Novy & Francis (1992) compared the split-half versions of the WUSCT (18 items each). They conclude “these results provide empirical justification for those users of the SCT who have the need for shorter, interchangeable, and reliable forms of the test.”[30] Holt (1980, p. 909), experimenting with a 12-item short form of the WUSCT found that inter-rate reliability was “at least as good as…reported by Loevinger; and the internal consistency…was quite adequate….Analyses of other data indicate that the short forms are representative samples of the full [WUSCT]”.[31] He goes on to say the data show that “an abbreviated form of Loevinger’s WUSCT is a reasonably reliable, feasible, and useful instrument for large-scale research…[and is]… a representative sample of the larger instrument, which probably gives substantially the same results” (p. 916), “…though it is clearly less satisfactory than the full 36-item form” (p. 915). Basic psychometric theory predicts that more evidence will result in better accuracy, so for individually-based assessments, done for coaching or consulting purposes, the full set of items is still recommended, but for research or group-statistical assessments, it would appear that shorter forms are quite valid.[32]

Variations in SCT stems. As to variations in the choice of sentence stems, we can make several observations. Loevinger adapted the sentence items numerous times before settling on a final version. There is nothing particularly special about the stems Loevinger used. Though they were carefully chosen and vetted; many were drawn from the experience of prior researchers, and the entire set evolved over the years before settling into the standard form used today. Others have used alternate forms tailored to men, women, or youth. Proposed new stems can be inadequate for a variety of reasons, e.g. they may be vague and thus understood in very different ways; they may coerce an overly limited range of responses; or they may introduce biases confounded with what the SCT is mean to measure. So new stems must be pilot tested for clarity and psychometric validity. But assuming that this due-diligence work is done to ensure that questions are adequate, overall the research strongly suggests that the overall properties of the SCT method, its strong psychometric properties, are robust to changes in the choice of sentence stems.

Ego development (meaning-making complexity) is a holistic capacity spanning all life-contexts (though we may exhibit maturity different than our “center of gravity” in any given context). The stems are meant to probe across a variety of contexts, and triangulate toward an overall measurement. Cook-Greuter (1999, p. 52) notes that “As Fischer, Hand, & Russell (1984) pointed out people tend to respond optimally to a task in ‘domains in which they are highly motivated.’ To tap this motivation, the SCT stems were devised to address ordinary everyday experiences shared across a wide spectrum of people.”

We have mentioned Kegan’s and Wilber’s framing of a holistic span of life contexts as including subjective, intersubjective, and objective (I/we/it) contexts. Loevinger (1985, p. 424) describes the span of stems in a related way: “Looking at item content, the stems can be classed as first person (My father— , When they talked about sex, I—), third person (Sometimes she wished that— , Usually he felt that sex—), and common noun or impersonal (A good father—, Being with other people—).”

Some stems seem to be sensitive to particular transitions along the developmental spectrum, and this is another reason for having an adequately diverse set of stems. For example, some stems are more related to impulse control (though one can give evidence about impulse control in any stem). Impulse control comes on line abruptly at conventional levels (second person perspective), and increases gradually or levels off for later levels. Therefore, sentences sensitive to impulse control are also sensitive to the transition from pre-conventional to conventional levels. Abstract and formal thinking begins at third person perspective with a qualitative leap, and increases gradually or levels off after that, so we would expect that certain stems are more sensitive to transitions in this part of the spectrum. So in general we would expect that, to a weak but statistically significant degree, certain sentence stems are better at signaling changes in specific levels (we are not aware of any detailed research results on this point).

Torbert and Cook-Greuter modified the stems to “omit a number of gender-based items and, includes work or leadership-related stems” (Torbert & Livne-Tarandach, 2009). Torbert’s LDP is shorter (24 items) and includes six new stems not in the WSUTC. Torbert (IBID, p. 134) reports that “the responses to the new stems correlate better with an individual’s overall profile rating than responses to the former stems did, thus improving the overall reliability of the measure.” Later we will discuss changes made in O’Fallon’s STAGES model.

Internal validity of the MAP, GLP, and LDP. As mentioned, Cook-Greuter’s, Torbert’s, and O’Fallon’s works builds upon Loevinger’s and branch off in several was. First, all have made minor modifications to the set of sentence stems. Second they have each repurposed Loevinger’s research-only methods for use in commercial coaching, consulting, and assessment ventures. Third, they include elaborated descriptions and scoring for the later stages, and they draw on populations consisting of more professionals or highly educated individuals. (O’Fallon diverges even more, as explained later.)

We have mentioned the implications of the first (stem modifications), and have also noted the second (commercialization). As to the third (later stages): theory predicts, and research indicates, that, because each level builds upon prior levels, that there are more degrees of freedom, diversity, and individuality in mean-making as stages progress. Later (post-conventional) levels have more linguistic variability in themes, styles, and syntactic complexity (though at the highest levels, Construct Aware and above, sentence completions tend to become shorter again).

Also, later levels are rarer than middle levels, making it more difficult for a research team or community of practice to consolidate upon the definition. In addition, above Construct Aware the scoring manual descriptions are less detailed and more vague. Because of these factors one can expect that the later the stage the more difficulty it may be to score (or to precisely define scoring criteria). Indeed trained scorers consider later levels more difficult to score (by anecdotal evidence). The diversity of responses and difficulty in scoring in part explains the fact that Cook-Greuter’s and Torbert’s studies tend to show lower internal validity vs. Loevinger’s. The statistics for these adapted instruments are still quite acceptable, however.