William R. Torbert*

Bill Torbert

*With deep thanks for the improvements suggested by Aliki Nicolaides, Mary Stacey, Richard Izard, Nancy Wallis, and Elaine Herdman-Barker.

As shown in this review, fifty years of research on real-world practice, guided by the Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry (CDAI) paradigm of social science and social action, have documented more powerful impacts than any other research and practice approach on leaders’ and organizations’ transformation (Fisher & Torbert, 1995; Taylor, 2017; Torbert, 1976, 1987, 1991; Torbert & Associates, 2004). CDAI is a rich combination of quantitative, qualitative, and action research in field settings where the researchers are also lead-participants studying themselves and their influence on the setting under study as it attempts to transform. In this early stage in the development of the CDAI paradigm, it is quantitatively anchored by the two psychometric instruments currently defensible for measuring and debriefing leaders’ developmental action-logics – the Mature Adult Profile (MAP) (Cook-Greuter, 1999, 2011) and the Global Leadership Profile (GLP) (Herdman-Barker & Torbert, 2012; Torbert, 2013, 2017).

This briefest possible summary of CDAI introduces the key terms “action inquiry practice” and “developmental theory of persons, organizations, and science,” as well as a brief history of the MAP and GLP psychometrics. Next, you will encounter a highly condensed, skeletal set of headlines to action inquiry studies and interventions in the realm of leadership and organizational development. The most practically and statistically significant studies are telegraphically presented, and are also referenced to refereed scholarly journals, PhD dissertations, and research volumes, so that you can dig deeper at will. See also McCauley et al. (2006) for an earlier peer review of the role of action inquiry in the field of developmental theory, research, and leadership.

The article then briefly discusses the implications of this body of work for the use of action inquiry, developmental theory, and the GLP in future leadership development and organizational transformation. The key point to remember is that one can ultimately learn action inquiry only through practice with others who are more mature in its practice.

Finally, in the appendix, the article reviews the rather complex history of reliability testing of successive sentence-completion instruments, from the WUSCT (Washington University Sentence Completion Test), to the LDP (Leadership Development Profile), and then to the MAP and the GLP.

Action Inquiry, Developmental Theory, and the GLP

Action inquiry is a lifelong practice for intentionally interweaving action and inquiry, both in the midst of action and in scientific inquiry, in order to achieve more frequent and more far-reaching timely and transforming action in new situations. Unlike most real-world action that is carried on with minimal inquiry, and unlike most scientific studies that offer only single-loop feedback to the scientific literature (hypotheses confirmed or disconfirmed), action inquiry generates single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback (Steckler & Torbert, 2008; Torbert, 2000b) during the course of the study in the field. (Double- and triple-loop feedback under conditions of mutual power are theorized as generating transformational change.)

Torbert & Associates (2004) currently offers the most comprehensive illustrations of first-, second-, and third-person action inquiry practice disciplines:

- for increasing one’s inner, first-person awareness and choice in the midst of one’s work and leisure;

- for increasing one’s second-person, interpersonal capacity to build trust, to co-resolve dilemmas, to test hypotheses in the midst of current action, and to take committed collaborative action in teams; and

- for increasing one’s third-person, organizational capacity to design, lead, and research the efficacy and transformational capacity of wider organizational systems.

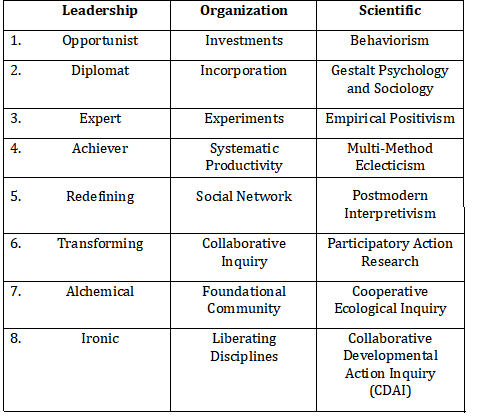

Developmental theory (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Erikson, 1959, 1969; Kegan, 1982, 1994; Torbert, 1976, 1987, 1991, 2004, 2013; Wilber, 2000) provides a lifelong perspective on how to engage in increasingly deep and timely action inquiry that makes fewer basic assumptions that can blind a leader or organization (or scientific method). Torbert’s developmental theory, in particular, posits that, beginning in childhood, we can develop through eight action-logics over a lifetime (though few today adventure beyond the first four); and that organizations and scientific methodologies can also develop to more complex and more present-centered action-logics (see Table 1). (It is important to note that the false assumptions of earlier action-logics can also apply to one’s initial understanding and use of this developmental theory itself [Herdman Barker and Wallis, 2016].)

One fundamental claim of CDAI is that the currently-rare, later-action-logic leaders and organizations and forms of social science (see Table 1) will exercise more moment-to-moment and day-to-day action inquiry, more mutual power, more double- and triple-loop feedback, and more timely action than earlier action-logics produce, thus engendering more personal and organizational transformation in turbulent environments and greater efficacy and sustainability in the long term. These developmental transformations are what have recently become known as ‘vertical’ development in corporate leadership development programs. Whereas conventional ‘horizontal’ leadership development programs are intended to increase leaders’ competence and efficiency within one’s current action-logic, ‘vertical’ development programs are intended to expand and support transformation of the individuals’ and organizations’ capacities and competence.

The theory and practice of Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry (CDAI) will likely be of interest to both practitioners and researchers, because it is the only developmental approach to have psychometrically measured and statistically validated its impact on leaders’ and organizations’ transformation to later developmental action-logics and greater real-world success. In addition, CDAI is the only ‘vertical,’ developmental, transformational approach that attends simultaneously to developing leaders (Torbert, 1972, 1991; Torbert & Fisher, 1992), to developing organizations (Torbert, 1987, 2013); to developing scientific methods (Chandler & Torbert, 2003; Sherman & Torbert, 2000, Torbert, 2000a, 2013); and to richly documenting the action inquiry process that generates such transformations (Torbert 1976, 2004).

The Mature Adult Profile (MAP) and the Global Leadership Profile (GLP) are similar psychometric instruments, based on a shared history, that measure a person’s current developmental action-logic. Starting in 1980, with Torbert as lead researcher and Cook-Greuter as high-reliability-trained scorer of the Loevinger Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT) (Loevinger, 1976; Loevinger & Wessler, 1970), they gradually transformed the WUSCT into the Leadership Development Profile (LDP) between 1980 and 2004. Cook-Greuter earned her doctorate for theoretical and empirical work on the scoring of late action-logics (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Torbert, 1987, 1991; Torbert, Cook-Greuter & Associates, 2004). Then, Cook-Greuter developed the MAP and Herdman-Barker and Torbert developed the GLP, each one a slight variant on the LDP. The specific studies reviewed in the next section will demonstrate the pragmatic and statistical power and validity of CDAI and the measure. The appendix will outline reliability tests of the related WUSCT, LDP, MAP, and GLP instruments, showing why the MAP and GLP are currently recommended.

Table 1: Leadership, Organizational, and Scientific Developmental Action-logics as Mapped by Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry (CDAI)

(Categories described in Torbert, 2004 & 2013)

The Efficacy of Action Inquiry

In Generating Leadership and Organizational Development

For practitioners who want to know why they should make any commitment at all to action inquiry and to later action-logic development, perhaps the most significant of our third-person research findings are the two studies that document: 1) the leadership action-logics under which organizational transformation to later action-logics is most likely; and 2) the organizational action-logic under which participants are most likely to transform action-logics. Each study yielded statistically valid results, beyond a .01 likelihood that the results are due to chance.

The Significance of Transforming Action-Logic CEOs. The first study (Rooke & Torbert, 1998; Torbert, 2013) focused on four lead consultants, working with ten different CEOs and organizations in six different industries over an average of four years. Five of the ten CEOs measured at the Transforming action-logic and five measured at earlier, conventional action-logics. The study found that there was a correlation, significant beyond the .05 level and accounting for 42% of all the variance, between the CEO’s action-logic and their organization successfully transforming (and improving on conventional indices of performance as well). If one added together the action-logics of the CEO and the lead consultant for each organization, the correlation became significant beyond the .01 level and accounted for 59% (Torbert, 2013).

Accounting for 59% of the variance means that the quality of the CEO’s and lead consultant’s action-logics, combined, made more of the difference between those organizations that successfully transformed and those that did not than all the other possible influences combined. The vast majority of third-person, empirical social science independent variables, including the “Big Five,” horizontal, personality tests often used by companies (Morgeson et al., 2007), typically account for only between 5-20% of variance in the dependent variables.

If it’s that important to successful organizational transformation to develop CEOs and other senior managers who are not just industry-savvy but also operate at the Transforming action-logic, then the additional question arises: What must an organization’s action-logic be to not only improve productivity and market performance, but also and simultaneously make leadership development an integral part of the organization’s everyday work activities (in other words, in Kegan’s (Kegan et al, 2016) recent terms, to create a “deliberately developmental organization”? The theoretical answer to this question, according to CDAI, is that the organization must: 1) have developed into the late action-logics itself (most effective will be an organization operating at the Liberating Disciplines action-logic); and 2) be guided by a CEO or leadership team operating at the Transforming action-logic or later.

The Significance of an Organization Operating at the Liberating Disciplines Action-Logic for Leadership Development. In our general field research, we have found no organizations fully operating at the Liberating Disciplines action-logic. But we have done both quantitative and qualitative, first-, second-, and third-person research in two organizations, parts of which were organized at the Liberating Disciplines action-logic (Torbert, 1991). These organizational divisions could be compared to the other, earlier action-logic parts of each organization. In both cases, the results showed that the Liberating Disciplines parts of the organizations were more successful in many ways. In the case where the psychometric measure was used (at that time, the LDP), it showed that, over a three year period, 91% of the members engaged in the Liberating Disciplines division transformed to a later leadership action-logic, whereas only 2% of those in the earlier action-logic divisions did so, a finding that accounted for an unusually high 81% of the variance (Torbert & Fisher, 1992).

The strength of the statistical findings in favor of CDAI theory, in these two before-and-after studies of the circumstances in which individuals or organizations are more or less likely to transform, is at first hard to understand and certainly invites further research. But, consider that the successful change leaders in all these cases were themselves operating at the late leadership action-logics. This means that they were practicing, and encouraging their members/clients to practice, first- and second-person action inquiry throughout the multi-year interventions on a daily and weekly basis, with single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback; as well as conducting third-person research and feeding it back at longer-term intervals. And they were doing all this much more regularly than leaders or organizational structures and cultures operating at earlier action-logics (see Chandler & Torbert, 2003, and Appendix of Torbert & Associates, 2004, for more detail).

Given these strong initial findings, let us take a closer look at further studies validating hypotheses linking later leadership action-logics to various ways of enacting leadership and to organizationally significant outcomes.

Action-Logic and Feedback-Seeking: Developmental theory predicts that at each later action-logic, people will be more likely to seek out and seriously consider feedback on the current situation, the wider temporal environment, and their performance. In one study (Torbert, 1994), two hundred and eighty-three members of an organization took the measure. They were also given the opportunity to sign up for feedback on their personal results (the sign-up was at a different time and place, in order to require a separate intentional action on their part). To confirm the theoretical prediction, the results should show that, in general, a larger proportion at each later action-logic asked for feedback.

What were the actual findings? None of those measured at the Diplomat action-logic signed up later for feedback. Ten percent of those measured at Expert signed up (and most of them strongly disputed the validity of the measure, without inquiry, during their individual debriefings). Forty-six per cent of the Achievers asked for feedback and were mildly confirming of the results as valid descriptions of them. Finally, everyone measured at the Redefining and Transforming action-logics asked for feedback; and they all also asked for a second debriefing session. Thus, the correlation between measured action-logic and proportion asking for feedback accounted for 100% of the variance; and, as just described, there was significant confirming qualitative data as well. The developmental theory and measure proved to be extremely powerful predictors of who seeks out feedback on their own performance voluntarily, presumably a significant variable in successful leadership.

Action-Logic and Position to Which Promoted in Organization. In another example (Torbert, 1991), six different studies (with a total of 497 participants), undertaken by five different researchers in different sectors (e.g. industry, health care, education) measured employees at different job levels from least to most autonomy/discretion (from first-line supervisor, to nurse, to junior management, to senior corporate management, to entrepreneurial CEOs). CDAI theory predicts that, on average, one would find leaders with more autonomy, discretion, and authority at later action-logics because they become more capable of managing wider time horizons, more uncertainty, and more complexity. In this set of empirical studies, the average action-logic rose, as predicted, level by level across the studies as autonomy/discretion increased, thus again accounting for 100% of the variance. Once again, the findings show the predictive power of both the developmental theory and the measure with regard to leadership capacity as determined in many different organizations. (It may also be noted that these aggregated studies found fewer than 2% of those below senior management measuring at the later Redefining or Transforming action-logics and only a little more than 15% even among those in senior management!)

A number of other studies using the measure with different dependent variables and methods have also statistically confirmed predictions of CDAI theory. Merron, Fisher & Torbert (1987) found that on a 34-item in-basket test, early-action-logic managers tended to handle items one at a time, whereas later-action-logic managers were more likely to organize the items strategically, were less likely to take the presented framing of problems for granted as correct, and were more likely to delegate in a collaborative and inquiring fashion (n=49, beyond .05 significance). Fisher & Torbert (1991) showed that late action-logic leaders described how they led subordinates, interacted with superiors, and took initiating action differently from early action-logic leaders, at a statistically significant level in the predicted directions. Also, Torbert (1987b) found that groups in the same organization with one or more late action-logic members performed better on three different indices than groups with none.

In addition, an increasing number of more recent articles, chapters, and PhD. dissertations are providing rich qualitative findings about the kinds of organizational action inquiry associated with different leadership action-logics:

1) how three university leaders, each measured at the Redefining action-logic, operate day-to-day (Yeyinmen, 2016)

2) how scientists at different action-logics act (Bannerjee, 2013)

3) how at each later action-logic between Redefining and Ironic, leaders engage with ambiguity and paradox more actively and creatively (Nicolaides, 2008)

4) how six executives in different sectors who were all measured at the rare Alchemical action-logic acted over prolonged periods of observation (Torbert (1996)

5) how first-, second-, and third-person action inquiry interweave in an organizational transformation intervention (McGuire, Palus, & Torbert, W., 2008)

6) how, at each later action-logic, persons are able to recognize and recover more quickly when their actions fall back unintentionally to an earlier action-logic (McCallum, 2008; Livesay, 2013)

7) how a college teacher enacts action inquiry, giving and receiving single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback, in the re-design and repeated implementation of a college course (Miller, 2012)

8) how action inquiry exercises can be designed and implemented in higher education (Rudolph, Taylor, & Foldy, 2001)

9) how a government leader develops an off-work action inquiry study group to support developmental transformation for herself and her colleagues (Smith, 2016)

10) how a regional planner engages in first-, second-, and third-person action inquiry with a traumatized First Nation community (Erfan, 2013)

11) how seven senior leaders spanning Expert, Achiever, and Redefining action-logics engaged in complexity leadership as defined in adaptive leadership theory (Presley, 2013)

12) how leaders responsible for implementing a Lean program in a university hospital setting varied in their approach according to action-logic (Byers, forthcoming 2018)

13) how Warren Buffett has progressed, across his lifetime from the Opportunist action-logic through six developmental transformations to the Alchemical action-logic (Kelly, 2013a, 2013b)

14) how seven members of a hospital executive team, measured at different action-logics relate to one another (Wallis, 2014)

These studies can be especially helpful to practitioners who have already been exposed enough to action inquiry and the developmental action-logics to know they want to learn more. Finally, the reader can find nine chapters illustrating various action inquiry methods in the references under Bradbury (2015).

Ethical, ‘Political,’ and Other Pragmatic Issues

When Coaches, Consultants, or Leaders Introduce Action Inquiry Practices To an Organization

According to CDAI theory, both leaders and organizations gain access to more types of power as they develop – first to additional types of unilateral power; and then at later action-logics to different types of mutual power. Unilateral power can make people conform (or rebel). Only mutual power can catalyze people to transform and become more free.

Table 2: Additional Type of Power Exercised at Each Later Leadership Action-logic

(Categories described in Erfan & Torbert, 2015, Bradbury & Torbert, 2016)

Because leaders and organizations increasingly exercise free choice and mutual power as they evolve to later action-logics, any organization members who may initially feel pressured into participating in action inquiry should soon find either increasing reasons to participate voluntarily or increasing opportunities to discontinue participating. This sense of voluntariness applies to taking the GLP, to participating in a ‘vertical’ leadership development program, or to practicing action inquiry as part of an organizational team or division adopting action inquiry methods for their everyday work.

The GLP is used by Certified GLP Coaches (of whom there are over 60 worldwide (see www.gla.global) to support the individual’s leadership development, typically with no organizational record of the person’s scores. If, however, the GLP is being used as one among a number of third-person measures in talent-hiring, talent-developing, or talent-promoting, it should never be used as a stand-alone hiring or promotion tool because, in each particular case, a candidate’s familiarity or unfamiliarity with the institutional context, as well as other variables, can play critical roles in his or her ultimate efficacy in the job. (After all, the finding that CEOs at the Transforming action-logic more reliably generate organizational transformation is based on CEOs who were hired without any explicit knowledge of developmental theory or the GLP.) Finally, if the GLP is being used with a whole team, the individual results should remain confidential, unless and until given individuals wish to share their results.

Another important issue to consider in organizational uses of the GLP is to whom the late action-logic ‘talent’ will report. One of the highest tension developmental conundrums occurs in an organization when later action-logic subordinates report to earlier action-logic superiors. The former may well find their latitude of discretion and action-taking infuriatingly reduced and will find it difficult not to become cynical about the superiors. The latter, in turn, will likely find their simplest directives annoyingly questioned and their authority in general undermined.

An even more generally unpropitious developmental situation frequently occurs when senior teams operating at early action-logics, individually and collectively, attempt to develop and implement by fiat a major new strategic direction, organizational transformation, or culture change. Without the senior team engaging, individually or collectively, in its own developmental transformation, the rest of the organization is likely to feel ill-led, to gain neither inspiration nor example from senior team actions, and to respond with low-risk, self-protective actions which lead to failure of the entire effort.

The good news is that it does not take many leaders at the Transforming action-logic or beyond on the executive team to develop a late action-logic organization over several years, where the majority of participants will experience at least one action-logic transformation and act more like transformational leaders. Transforming leaders lead toward collective leadership. Recognizing that every action one takes has transforming potential can help one identify the general path toward increasingly transformative leadership (Montuori & Donnelly, 2017). In addition, awareness of differences among developmental action-logics and enactment of action inquiry practices can support leaders and organizations to travel that path.

In Sum

In sum, Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry (CDAI) is an approach to leadership development and organizational transformation (and social science too) that offers neither quick nor permanent solutions, but rather a guide for continually intensifying inquiry and the increasingly apt and timely use of late action-logic mutually-transforming power in particular situations and different contexts.

Relatively few organizational leadership groups or social scientists are initially likely to be attracted to CDAI because it is not a quick-fix and because it demands that they themselves transform more than once through the day-to-day practice of action inquiry. On the other hand, the sooner leaders and organizations choose to start out on this steep path, the more of a competitive and collaborative advantage they are likely to build. And the sooner social scientists commit to first-, second-, and third-person CDAI methodologies, the more quickly the whole CDAI approach will be fleshed out and amended by new findings.

The GLP is a rare psychometric instrument that has been adapted to provide feedback (via a 30+ page report, including a personal commentary) to persons who complete it. The results can orient a person to where he or she is on the path of adult development and where the next way station on the climb is. The power of the instrument lies in the inquiry it helps to release within the individual and in the discussion it prompts within the team or organization. But what’s most important for transformation toward personal integrity, interpersonal mutuality, and organizational and societal sustainability is exercising action inquiry in practice (Marshall, 2016).

Appendix: The Reliability of the GLP, the MAP, and Related Measures

The GLP (Herdman-Barker & Torbert, 2012) is grounded originally in Loevinger’s Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT) (Loevinger, 1976; Loevinger & Wessler 1970), and four-fifths of the GLP sentence stems are also WUSCT sentence stems. Unlike many other psychometrics, like the “Big Five” personality test, which ask for easily-fake-able self-descriptions on quantitative scales (Morgeson et al., 2007), the “sentence completion” methodology asks for action decisions about what to write in response to the stimulus of each stem. These are not only closer analogies to other everyday actions, but have also proved very difficult to fake (Redmore, 1976).

Loevinger’s measure displayed high reliability and internal validity for assessing the four early action-logics, but less theoretical coherence or external validity in the field for the later action-logics. (See review of WUSCT reliability and validity testing in Appendix of Torbert & Associates, 2004, Westenberg et al, 1998).) The Loevinger measure also has low face validity for use in feedback to or action research and leadership development with practitioners, because its language tends to sound evaluative and there are no leadership stems.

When Cook-Greuter and Torbert began working together on developing the Leadership Development Profile in 1980, she was already a high-reliability WUSCT scorer. Torbert’s action research focus was on testing the external validity of the instrument, on learning whether later action-logic leaders were in fact better, as predicted, at helping organizations transform, and on how to support leadership development. Were the scoring of the LDP (and later the MAP and the GLP) not reliable (and therefore more random), the field experiments reported in the body of this paper could not have accounted for such high percentages of the variance at such high levels of statistical significance.

Revised definitions, field manuals for scoring, feedback materials, and initial reliability tests for the four later action-logics were completed by Cook-Greuter (1999) in conjunction with a wide range of Torbert’s laboratory and field action research projects in those years (1980-2004) (Torbert, 1987, 1991, Fisher & Torbert, 1995, Rooke & Torbert, 1998; Torbert, Cook-Greuter & Associates, 2004). Elaine Herdman-Barker received most of her training as a scorer from Cook-Greuter, developing the necessary reliability (80% or better perfect agreement with another scorer-in-training [84% in their case]) soon after Cook-Greuter discontinued her work with the Harthill LDP and created the MAP.

As doyenne of scoring for the former LDP and now the MAP, Cook-Greuter has continued to train and assess the reliability of other MAP scorers and is trusted as objective within the Integral community (this is an important second-person validity test in CDAI). But she has not, insofar as this author can ascertain, published reliability figures either in peer refereed journals or publicly available white papers over the past fifteen years (an important third-person test of validity in both empirical positivism and CDAI). In response to an email from the author requesting such information, Cook-Greuter responded, with permission to quote: “The MAP has the most extensive and updated reference manuals. Our certified scorers/coaches attend monthly scoring discussions to refine their theoretical understanding as well as to hone their scoring and interpretation skills. Most importantly, the resulting profiles and required debriefs have very high face-validity.”

After Harthill claimed the LDP in its then-current form as its intellectual property (though it could not claim the Loevinger sentence stems and scoring manuals, which are in the public domain), Torbert and the two reliable LDP scorers created the GLP and discontinued work with the LDP. Although the Harthill LDP continues to be commercially available, how it has trained its current scorers is unknown, and it has conducted and published no known reliability or validity tests. Thus, it currently has no known scientific basis and cannot be recommended. Another new developmental measure, the O’Fallon StAGES, also lacks published reliability and validity tests, but in this case research and publication are known to be underway (see September 2017 issue of Integral Leadership Review).

By 2012, Herdman-Barker and Torbert had further revised the scoring manuals for the GLP and had developed several new sentence stems and manuals that probed significant business dimensions previously missing (e.g. power and time). The two reliable GLP scorers have continued to have their reliability tested over the years, by a different method than traditionally used, with some of the results published in a peer-reviewed journal (Livne-Tarandach and Torbert, 2009; Torbert, 2013) and some in a white paper (Torbert, 2017). The new type of reliability test emerged from the desire to give clients and action research participants the most accurate possible data (their quantitative, current-action-logic score), as well as the most useful and artistic interpretations of a GLP-trained commentator. To do this, Torbert and Herdman-Barker decided to review every score and every commentary. The aim was to highlight the differences between the two scorers (or commentators), then review them together, explore the disagreement in terms of each person’s rationale (referring to the scoring manuals), and agree on a final score (or commentary), which was presumably more often accurate than either of the individual sets of scores.

Several years later, we realized that we could use our accumulated data as a new kind of reliability test. This kind of reliability test has been conducted twice in recent years on the GLP scorers. In a review of 805 measures (Livne-Tarandach & Torbert, 2009), each of which could have been scored at 13 different levels (e.g. Early Diplomat, Diplomat, Late Diplomat, etc., the results showed perfect agreement between the two scorers in 72% of the cases, with a 1/3 action-logic disagreement in 22% of the cases, with only one case of a disagreement larger than one full action-logic, resulting in a .96 Pearson correlation between the two scorers. In early 2016, a stratified sample of the 78 most recent GLP sentence completion forms from 2015 (10 Expert, 20 Achiever, 20 Redefining, 20 Transforming, and 8 Early Alchemical) were reviewed for reliability between the same two scorers, in terms of total protocol scores. This study found perfect agreement on the protocol score in 94% of the cases and only a 1/3 action-logic disagreement in the other 6%. When one compares these results to the ones seven years previously by the same two GLP scorers, one sees a 22% increase in perfect agreement. This increase in agreement presumably occurs at least in part because of the continuing, measure by measure comparisons of scores between the scorers throughout the years.

Finally, in late 2016, two new GLP scorers completed their training with Elaine Herdman-Barker. A test of reliability between the new scorers’ ratings of each of the 30 sentence stem responses on 30 protocols (n=900) and Herdman-Barker’s scores (of which the new scorers were unaware) show the levels of precise agreement at 87.1% and 87.4%, with a disagreement of two levels occurring in less than 1% of the cases.

References

Banerjee, A. (2013). Leadership development among scientists: Learning through adaptive challenges (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Bradbury, H. (Ed.)(2015). Handbook of Action Research, Vol III. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Chapters on Action Inquiry by Practicing Action Inquiry Fellows:

Nancy Wallis, “Unlocking the Secrets of Personal and Systemic Power: The Power Lab and action inquiry in the classroom”

Steve Taylor, Jenny Rudolph, and Erica Foldy, “Teaching and Learning Reflective Practice in the Action Science/Action Inquiry Tradition”

Grady McGonagill and Dana Carman, “Holding Theory Skillfully in Consulting Interventions”

David McCallum and Aliki Nicolaides, “Cultivating Intention (as we enter the fray): The skillful practice of embodying presence, awareness, and purpose as action researchers”

Elaine Herdman-Barker and Aftab Erfan, “Clearing Obstacles: An exercise to expand a person’s repertoire of action”

Hilary Bradbury, “The Integrating (Feminine) Reach of Action Research: A nonet for epistemological voice”

Erica Foldy, “The Location of Race in Action Research”

Lisa Stefanac and Michael Krot, “Using T-Groups to Develop Action Research Skills in Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Environments”

Aftab Erfan and Bill Torbert, “Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry”

Bradbury, H. & Torbrt, W. (2016). Eros/Power: Love in the Spirit of Inquiry. Integral Publishers, Tucson AZ.

Byers, E. (2018). Adult development and the application of lean management in health care (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University, NY.

Chandler, D. & Torbert, W. (2003). Transforming inquiry and action: 27 flavors of action research. Action Inquiry. 1(2), 133-152.

Cook-Greuter, S. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement, Unpublished Harvard University doctoral dissertation, Cambridge MA.

Cook-Greuter, S. (2011). A report from the scoring trenches. A. Pfaffenberg, P. Marko & A. Combs (Ed.s), The postconventional personality. SUNY Press, Albany NY. 57-74.

Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. NY, International University Press.

Erikson, E. (1969). Gandhi’s truth. NY: Norton.

Fisher, D. & Torbert, W. (1991). Transforming managerial practice: beyond the Achiever stage. In Woodman, R. & Pasmore, W. (ed.s) Research in Organizational Change and Development (vol. 5). JAI Press, Greenwich CT. 143-174.

Fisher, D. & Torbert, W. (1992). Autobiographical awareness as a catalyst for managerial and organizational development. Management Education and Development Journal (23) 3, 184-198.

Fisher, D. & Torbert, W. (1995). Personal and organizational transformations. London: McGraw-Hill.

Herdman-Barker, E. & Torbert, W. (2012). The Global Leadership Profile Report. Accessible via www.gla.global

Herdman-Barker, E. and Wallis, N. (2016). Imperfect leadership: Hierarchy and fluidity in leadership development. Challenging Organisations and Society Journal, 5(1) 866-885.

Kelly, E. (2013a). Transformation in leadership, part 1: A developmental study of Warren Buffet. Integral Leadership Review. Integralleadershipreview.com. March.

Kelly, E. (2013b). Warren Buffett’s transformation in leadership, part 2. Integral Leadership Review. Integralleadershipreview.com. June.

Livesay, T. V. (2013). Exploring the paradoxical role and experience of fallback in developmental theory (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of San Diego. San Diego CA.

Livne-Tarandach, R. & Torbert, W. (2009). Reliability and validity tests of the Harthill Leadership Development Profile in the context of Developmental Action Inquiry theory, practice and method. Integral Review. 5 (2) 133-151. 2009.

Loevinger, J. & Wessler, R. (1970). Measuring ego development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Loevinger, (1976). Ego development: Conceptions and theories. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass.

McCallum, D. C. (2008). Exploring the implications of a hidden diversity in group relations conference learning: A developmental perspective (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University, NY.

McCauley, C. Drath, W., Palus, C., O’Connor, P. & Baker, B. (2006). The use of constructive-developmental theory to advance the understanding of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 634-653.

McGuire, J., Palus, C. & Torbert, W. (2008). Toward interdependent organizing and researching. In A. Shani et al. (Eds.), Handbook of collaborative management research, Sage, Thousand Oaks CA. 123-142.

Marshall, J. (2016). First-person action research: Living life as inquiry. London, Sage.

Merron, K., Fisher, D. & Torbert, W. (1987). Meaning making and managerial action. Journal of Group and Organizational Studies. 12 (3), 274-286.

Miller, C. (2012). The undergraduate classroom as a community of inquiry (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of San Diego, San Diego, CA.

Montuori, A. & Donnelly, G. (2017). Transformative leadership. In J. Neal, Handbook of Personal and Organizational Transformation. Springer International Publishing. 1-33.

Morgeson, F., Campion, P., Dipboye, R., Hollnbeck, J., Murphy, K., Schmitt, N. (2007). Reconsidering the use of personality tests in personnel selection contexts. Personnel Psychology. 60(3), 683-729.

Nicolaides, A. (2008). Learning their way through ambiguity: Exploration of how nine developmentally mature adults make sense of ambiguity in times of uncertainty. (Doctoral Dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University, NY.

Presley, S. (2013). A constructive-developmental view of complexity leadership (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA.

Redmore, C. (1976). Susceptibility to faking of a sentence completion test of ego development. Journal of Personality Assessment, 40(6), 607-616.

Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s developmental stage, Organization Development Journal, 16, 11-28.

Rudolph, J. Taylor, S. & Foldy, E. (2001). Collaborative off-line reflection: A way to develop skill in action science and action inquiry. In Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. (Eds.), Handbook of action research, Sage Publications, London. 405-412.

Sherman, F. & Torbert, W. (Ed.s). (2000). Transforming social inquiry, transforming social action: New paradigms for crossing the theory/practice divide. Norwell MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Smith, S. (2016). Growing together: The evolution of consciousness using collaborative developmental action inquiry (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Steckler, E., & Torbert, W. (2010). Developing the ‘Developmental Action Inquiry’ approach to teaching and action researching: Through integral first-, second-, and third-person methods in education. In S. Esbjorn-Hargens et al (Ed.s) Integral Education. Albany NY: SUNY Press. 105-126.

Taylor, S. (2017). William Rockwell Torbert: Walking the talk. Szabla et al. (ed.s) The Palgrave Handbook of Organization Change Thinkers. Macmillan, NY.

Torbert, W. (1972). Learning from experience: Toward consciousness. Columbia University Press, NY.

Torbert, W. (1976). Creating a community of inquiry: Conflict, collaboration, transformation. Wiley, London.

Torbert, W. (1987). Managing the corporate dream: Restructuring for long-term success. Dow Jones-Irwin, Homewood, Il.

Torbert, W. (1987b). Education for organizational and community self-management. In Bruyn, S. & Mehan, J. (ed.s) Beyond market and state. Temple University Press: Philadelphia PA. 171-184.

Torbert, W. (1991). The power of balance: Transforming self, society, and scientific inquiry, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Torbert, W. (1994). Cultivating post-formal development: higher stages and contrasting interventions. In M. Miller, et al. (Ed.s) Transcendence and mature thought in adulthood. Lanham MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 181-204.

Torbert, W. (1996). The ‘chaotic’ action awareness of tranformational leaders. International Journal of Public Administration 19 (6), 911-939.

Torbert, W. (2000a). A developmental approach to social science: Integrating first-, second-, and third-person research/practice through single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback. Journal of Adult Development. 7 (4) 255-268.

Torbert, W. (2000b). The challenge of creating a community of inquiry among scholar-consultants critiquing one another’s theories-in-practice. In Sherman, F. & Torbert, W. (Ed.s). Transforming social inquiry, transforming social action: New paradigms for crossing the theory/practice divide. Norwell MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 161-188.

Torbert, W. (2013). Listening into the dark: An essay testing the validity and efficacy of Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry for describing and encouraging the transformation of self, society, and scientific inquiry. Integral Review. 2013, 9(2), 264-299.

Torbert, W. (2017). Brief comparison of five developmental measures: the GLP, the LDP, the MAP, the SOI, and the WUSCT. White paper, available via www.gla.global

Torbert, W. and Fisher, D. (1992). Autobiography as a catalyst for managerial and organizational development”, Management Education and Development Journal, 23, 184-198.

Torbert, B., Cook-Greuter & Associates. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transformational leadership. Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco.

Westenberg, M., Blasi, A. & Cohn, L. (1998). Personality development: Theoretical, empirical and clinical investigations of Loevingeer’s conception of ego development. Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum.

Westenberg, M., Drewes, M., Goedhart, A., Siebelink, B., & Treffers, P. (2004a). A developmental analysis of self‐reported fears in late childhood through mid‐adolescence: Are social‐evaluative fears on the rise? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(3), 481-495.

Wallis, N. (2014). Insights from intersections: Using the Leadership Development Framework to explore emergent knowledge domains shared by individual and collective leader development. In Scala, K., Grossman, R., Lenglachner, M., and Mayer, K. (Eds.), Leadership learning for the future – A volume in Research in Management Education and Development. Information Age. 185-201. Publishing, New York.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology. Shambhala: Boston.

Yeyinmen, C. (2016). Uses of complex thinking in higher education adaptive leadership practice: A multiple-case study. (Doctoral Dissertation) Harvard University: Cambridge MA.

Yeyinmen, C. (2016). Uses of complex thinking in higher education adaptive leadership practice: A multiple-case study. (Doctoral Dissertation) Harvard University: Cambridge MA.

About the Author

William Torbert: Having received both his BA in Politics and Economics and his PhD in Individual and Organizational Behavior from Yale, Bill served as Founder and Director of both the War on Poverty Yale Upward Bound Program and the Theatre of Inquiry. He also taught leadership at Southern Methodist University, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and then, from 1978-2008 at the Carroll Graduate School of Management at Boston College, where he also served as Graduate Dean (the BC MBA program’s ranking rising from below the top 100 to #25 during his tenure) and later served as Director of the Organizational Transformation Doctoral Program.

In addition to consulting to dozens of companies, not-for-profits, and governmental agencies, Torbert has served on numerous Boards, notably at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care when it was rated the #1 HMO nationally in the US; and, for twenty years, at Trillium Asset Management, the original and largest independent Socially Responsible Investing firm… founded by Bill’s friend Joan Bavaria… a rare CEO who was at once visionary, strategic, executive, and also truly collaborative.

Pingback: 11/30 – Well here we are... - Integral Leadership Review

Pingback: The Pragmatic Impact on Leaders & Organizations Of Interventions Based in the Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry Approach | Leadership Explorer Tools