Tracy Cooper

Tracy Cooper

“It seems to me what is called for is an exquisite balance between two conflicting needs: the most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses that are served up to us and at the same time a great openness to new ideas. Obviously those two modes of thought are in some tension. But if you are able to exercise only one of these modes, whichever one it is, you’re in deep trouble” –Carl Sagan

The notion of how to teach graduate students to think critically and enact a lifelong love of learning seems to be a perennial problem that higher educators face. More so, how to teach graduate students to think creatively seems to be an even greater problem when we consider the depth to which many people are unable to meaningfully engage with creativity because they subscribe to fallacies regarding its existence within themselves or its utility. In the online environment of many modern universities the issue of how to remove obstacles to creative thinking is further exacerbated by the emphasis on criticality as a preferred approach to thinking that is rational, evaluate, and reductive (Bailin et al., 1999; Phillips & Bond, 2004; Pithers & Soden, 2000). In sum, we are faced with not only the problem of teaching the practice of critical, creative thinking but also how to mitigate institutional hurdles that may be at odds with a full realization of the strengths in a creative criticality.

In this paper, I consider the necessity of teaching critical thinking to online graduate students enrolled in liberal arts, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary programs as a lifelong practice while offering a model of critical thinking that places equal value on creative thinking. In fact, I believe the two to be inseparable. My argument lies in the imperative to demystify the nature of creativity, while re-emphasizing the crucial role of critical thinking in modern society as a means of solving complex problems. As higher education professionals tasked with providing programs that teach students to “ask better questions,” “explore perspectives that are not your own,” and “see connections between disciplines” I offer the perspective that creativity is for everyone, in every place, and every day, while critical thinking is the “disciplined art of ensuring that you use the best thinking you are capable of in any set of circumstances” (Paul & Elder, 2014). It will be through educating students to be critical AND creative thinkers that we will begin to permeate society with graduates capable of lifelong improvement in thinking skills, broadened perspectives that privilege empathy for other viewpoints, and raise the bar for intellectual performance enhanced by the human potential for creative innovation coupled with the “skeptical scrutiny” of Carl Sagan.

THE CHALLENGE

Online graduate degree programs have enjoyed a rise in popularity due to improvements in internet connectivity, demands of the workplace requiring often odd work hours for adult learners, and family responsibilities often impeding the adult student’s ability to attend brick-and-mortar universities. Additionally, many institutions of higher learning have found it to be cost-effective to employ faculty working from home, while allowing them greater freedom to pursue their professional careers. Couple this with the rise in adjunct teaching and a new emphasis on graduate education that can meet the needs of industry for graduates with so-called “soft skills,” i.e., empathy, effective interpersonal communication skills, active listening, and mentoring of others and the challenge is clear: how to impart harder to learn “soft skills,” while ensuring students mesh them with solid critical thinking abilities. There is another aspect of online graduate programs that merits examination as I define the problem and that is how to create a sense of buy-in on the part of faculty to implement learning that may differ to some degree from their disciplinary backgrounds.

Faculty are the obvious backbone of any higher education program with courses being conceived, designed, and executed under their watchful eyes and skilled attention. As with any endeavor it is likely that faculty tire of repetitive courses that vary little in content or student population. Teachers are, as the old saying goes “human too” with all the same human needs for variety, autonomy, connection, and feedback as any other individual in society. When we employ highly educated teachers to navigate an online environment they may not be altogether comfortable or familiar with we almost ensure each teacher has an expiration date on which they will seek greener pastures with fresh challenge and meaning. Many adjunct faculty members report the same symptoms of isolation, disconnection, and anonymity as do students in online programs. The challenge then becomes how do we engage students AND faculty in an ongoing, dynamic process of give and take that keeps learning alive and active while accomplishing programmatic and institutional missions and goals?

The nature of any liberal arts program is unique by its very mission. Whereas universities have adapted to society’s need for specifically educated workers there exists a necessary foundation in broad-based scholarly inquiry if an individual is to exhibit the kind of complexity-oriented approach that can consider a multiplicity of perspectives in addressing a problem. As the world is only becoming increasingly complex and difficult to navigate in terms of thinking the foundational aspect of many universities that started as liberal arts colleges becomes even more imperative to honor and translate into a modern 21st century format capable of accommodating the diverse needs of a workforce forever in search of matching the right skills to the right position in a “gig” economy.

Coursework must also be taken into account due to the liberal arts typically appropriating greater latitude in approach to a given topic. You might have a course such as Zombies in Film, or Art, Consciousness, and Diversity, even Sociology of the Mafia. All of which might sound a bit odd or different, until you recognize and appreciate how students are allowed to explore freely (to a certain extent) while they are growing and developing intellectual prowess. Liberal arts programs serve a vital need to broadly educate people in a deeper way but many adult students possess often significant work experience in disciplinary career fields. Many students enter liberal arts programs to study in a specific area (music, history, management) and derive the benefits of broad-based inquiry, most of which are typically far greater than they could have imagined. Finding ways to adequately do justice to the twin needs of students and faculty for meaningful engagement with capacities, critical reflection, and perspective shifts requires that we rethink the nature of critical and creative thinking.

CRITICAL THINKING

“Because few people realize the powerful role that thinking plays in their lives, few gain significant command of their thinking. Therefore, most people are in many ways “victims” of their thinking–harmed rather than helped by it. Most people are their own worst enemy… think at the unconscious level most of the time, never putting the details of their thinking into words…they have little command of their thinking…they are unable to adequately analyze and assess their thought” (Paul & Elder, 2014, p. xv).

The above statement might seem antithetical in a sense to higher education professionals who are in the business of broadening minds and expanding horizons (so to speak), yet few of us consider that critical thinking should be a practice one learns and develops over a lifetime of conscious effort. The ability to think in a very disciplined way, while reflecting on our thinking processes with an aim toward improving them effectively encapsulates what we mean by critical thinking. Far from wishing to be “victims” of our thinking we should wish to enhance and expand our capabilities while acknowledging improvement will be a lifelong process. We should also seek to model that practice to others, in our case, to graduate students who are in class for that specific purpose. Before we move too deeply into our broader conceptualization of critical thinking let’s first consider the history of critical thought to provide a sense of context.

The roots of western critical thinking go back to Socrates some 2500 years ago with a method of using logic to ask probing questions dispelling a lack of evidence, often from commonly held beliefs no one had yet been able to challenge in a systematic way. For Socrates power and position were no guarantee of logic, instead he taught that we must profoundly question with deep probing to get at the truth. If an idea is worthy of belief it must be able to stand up to intense questioning to ascertain whether the belief is reasonable and rational (Paul, R., Elder, L., & Bartell, T., 1997). Rene Descartes carried this inquiry into questioning further with his famous meditations resulting in the profound Cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am) but also leading us to dualism, which had existed for the ancient Greeks, but Descartes made explicit as what would be known as Cartesian Dualism. Descartes’ mechanistic view of the world separated mind from body but laid the foundation for Enlightenment thinking.

The French Enlightenment (the Age of Enlightenment or Age of Reason) further posited that the human mind functions better when disciplined with reason and utilized to seriously critique and analyze beliefs and claims. The French attitude of Sapere aude (dare to know) marked this period as did the use of the scientific method as a way of arriving at better solutions through trial and error. Later thinkers would begin to apply these approaches to a wide variety of fields including the natural and social sciences and including figures such as Sigmund Freud, August Compte, and Karl Marx. In the 20th century W.G. Sumner concluded that “education is good just so far as it produces a well-developed critical faculty” (Sumner, 1906). The production of a critical mind that is capable of questioning, wondering, and doubting is a mind that never ceases to grow or evolve.

The long thread of continuity that defines our slow march to better thinking has contained within it the seeds of potentiality. At times, we have made major strides forward and all throughout the 20th and, now into the 21st century, we have doubled our knowledgebase many times over and at an ever-increasing rate. Critical thinking has, to some extent, suffered from atrophy, since it may be considered a given among many people. Educators in a study by Paul, Elder, and Bartel (1997) agreed that critical thinking is important to teach (some 89% agreed that it is an important goal) but few can relate quantifiable standards for critical thinking that can be taught to students in a systematized way that both stays with students and meets the goal of improving our thinking over the life course resulting in the attainment of intellectual traits. In the same study only 19% could relate a cogent explanation of critical thinking and only 9% teach for critical thinking on a daily basis. I suggest that the Paul-Elder approach has already provided a way to implement an accessible, relatable, intellectually rigorous practice that may be taught to students and faculty. The Paul-Elder approach is theoretically grounded, broadly applicable, and represents a strong general critical thinking model.

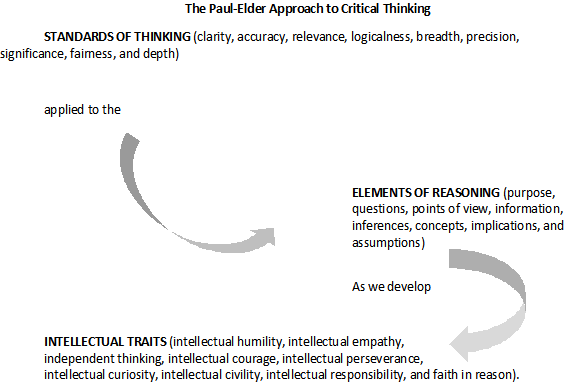

Richard Paul and Linda Elder (1997, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2014) of the Center for Critical Thinking at Sonoma State University developed an approach to critical thinking that envisions applying universal standards of thinking to universal elements of reasoning as we learn to develop intellectual traits. Paul and Elder’s approach to thinking emphasizes the development and nurturing of strong-sense critical thinking over weak-sense thinking. It is through acknowledging our poor thinking with all its associated costs (egoism, frustrations with unsolved problems, and pain caused by mediocre quality thinking) that we can begin to “think about our thinking with a goal of improving our thinking,” as Richard Paul often stated. Critical thinking has been defined by Facione (1990) as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based.” Further, for Paul and Elder, critical thinking should be a lifelong practice that we teach to everyone as a means of ensuring fairminded critical thinking or thinking that takes into account viewpoints that contradict our own.

In real terms, students use the elements of reasoning to address the issue at hand and assess their thinking using the standards of thinking. Over time student’s thinking will improve as they engage deeply with the concepts and find practical utility in their lives and careers. Critical thinking has a number of strengths, among them: critical thinking is a systemized way of reflectively weighing and assessing issues and options; can be learned and therefore is never lost as a means to improve human lives; and allows us to refrain from being subjected to the opinions and beliefs of others who may not have formulated their positions on facts, evidence, or reasonable foundations of logical thought. The Paul-Elder model represents a general model that may be taught to anyone of any age as they think about their thinking or the thinking of others. The model is simple yet powerful, rigorous yet flexible, and is communicable to a wide audience that may apply their learning immediately in their professional and personal lives. This immediate positive feedback loop becomes self-perpetuating as students quickly realize the power of being able to self-monitor their thinking and self-correct as necessary.

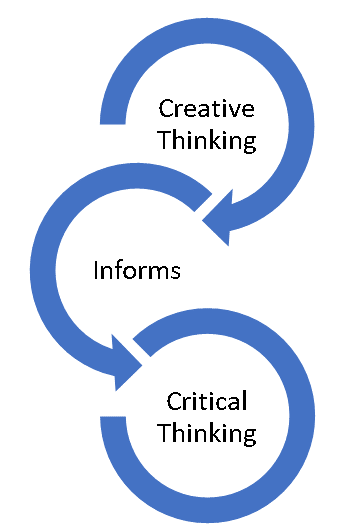

Critical thinking by itself, though a powerful tool to aid in decision-making and inquiry, suffers from an inherent weakness: namely one can only analyze the options that are apparent from ordinary thinking. Carl Sagan recognized it many decades ago when he observed we need the “most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses combined with a great openness to new ideas.” In effect, we not only need a well-developed critical faculty but also a well-developed complementary capacity for creative thinking.

CREATIVE THINKING

The history of creative thinking is the history of creativity which I cannot hope to cover in this brief paper but which I will show is inseparable from critical thinking and, in fact, should be explicitly associated with it. Our creative capacities have been inherent in our species since the dawn of time. Homo sapiens sapiens are the “wise man” of the great ape kingdom and have survived natural calamities, manmade disasters, and spread across the Earth to inhabit places hospitable and not-so-hospitable to life. We very clearly are a clever species with imagination, a drive to explore, and boundless creativity.

Creativity involves “a network of interactions and may be thoug

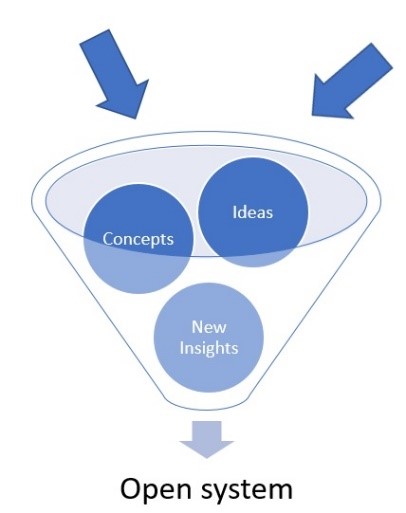

ht of as a phenomenon that occurs in the context of multiple systems (Montuori, 2011).” Following an open systems concept creativity is a living system that needs interchange for its survival and flourishing. The creative thinker has never flourished in a closed system with few to no new inputs. For creative thinking to take place one must be open to new experiences, sensitive to the inner and outer environments, curious about the world and its rich possibilities, and possess a complex, messy nature that is, at once, rooted in solidity yet equally rooted in spontaneous inputs (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Creative thinkers are paradoxical by nature displaying dichotomous preferences across the range of traits that may make them uniquely capable of embracing multiple ways of being and knowing (Cooper, 2015). Creativity, though usually thought of in terms of the process of creating an end product is a much more profound, yet simple concept and capacity in humans. Creativity is simply allowing the inputs of new ideas, concepts, and stimulation to enter our living, open system where they may be reflected upon in service to new possibilities.

THE PROBLEM OF CREATIVITY

It is often the case that when we hear the term “creative” we automatically think of an end-product like a painting, sculpture, or performance while completely ignoring that being a creative thinker and doer is a way of being, knowing, and acting in the world. In the US, many people think of creativity as relegated to the realm of the artist, performer, or craftsman, but rarely as something they feel capable of in any significant sense. It’s not their fault, this is how they have been conditioned by an educational system geared toward producing a graduate best suited to the needs of industry and a society that has come to think of creativity (and creative thinking) in generally uneasy terms. Our educational system has, as well, focused more on reproductive education than on the type of broad education we need to adequately address real-world issues from a complexity standpoint (Amabile 2010; Florida 2002, 2004; Friedman 2009; Gidley 2010; Jensen 2001; Montuori 1989, 2011a; Robinson 2001, 2009; Sardar 2010). The more our society allows itself to be obsessed with metrics demonstrating proficiency at recalling facts without context, rote memorization, and test-taking the further we banish creativity from our classrooms. Ironically, creativity has become even more essential to many people as they seek greater self-realization, fulfillment, and self-reinvention (Florida 2002; Pink 2006).

The problem for creativity is that we privilege the logical over the intuitive, the “sure thing” over the “let’s see what happens,” and the constricted over the expansive. Creativity and creative thinking require that we open ourselves to the rich vein of possibilities inherent in the world, and in our minds, bodies, and hearts. Creative thinking connects us to each other, to nature, and to the infinite. Why then do we allow creative thinking to play second fiddle to processes that would otherwise be enriched and enlivened by its very presence? It is my position that while most people will pay token lip service to the value of creative thinking most will shy away when things become messy and unsure. Albert Einstein is purported to have once said, “the intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” In a study conducted to better understand the paradox between desiring creativity while feeling threatened by it Mueller, et al (2011) ascertained that when we feel uncertainty (as is often the case when we explore freely) it provokes a negative bias against the uncertainty with a preference toward the status quo, the certain, and stable. When this bias is activated we may lose sight of what creative thinking even looks like leaving us searching for solutions using only part of the tools available to us as creative beings. I propose a new approach to thinking critically that acknowledges that creative thinking is inseparable from critical thinking to explicitly recognize the synergistic role they both play in generating and assessing novel possibilities, new ways of thinking, knowing, and being that account for the whole person, and that will allow graduate students to develop a broader practice of critical, creative thinking rooted in a greater breadth and depth of understanding that forms the basis for connectivity from which all creativity springs.

CREATIVE INQUIRY

There are many ways to utilize creativity but here I would like to offer that creativity may be used in scholarship as a means of moving beyond the dualism that so often mires thinking in reproductive modes of education. Reproductive Education views learners as spectators or consumers of knowledge created by others (Montuori, 2011). Since the focus of most graduate programs is to produce independent thinkers capable of creating original scholarship, especially within liberal arts and transdisciplinary programs, the mere regurgitation of a known product will not spur innovation, progress, or illumine complex problems requiring more multifaceted approaches. Creative Inquiry was developed to outline an approach to learning where creativity is an emergent process instigated by the learner as she recursively explores scholarship and produces knowledge (Seel, 2012). Creative Inquiry draws from fundamental assumptions, increasingly informed by science, where humanity, Nature, indeed the Universe is an open, creative process with the learner as an open system capable of absorbing influences from the external world and reflecting on the internal world of discovery, wonder, and invention. Complexity science and constructivism form the epistemological perspective along with creativity research and a range of multi-disciplinary scholarship (Montuori, 2011) that sees knowledge creation as an active, engaged, relational, paradoxical process centered

on the learner remaining open to the ambiguity of the unknown rather than imposing a rational framework on an unpredictable

system (Montuori & Donnelly, 2013). Creative Inquiry moves us beyond being consumers of knowledge to active producers of knowledge that is contextualized, synergistic, and ongoing.

Creative Inquiry has been used as the basis for scholarship in at least one Ph.D. program and a master’s program at the California Institute of Integral Studies and is embedded in many other programs in various forms. Here I suggest that the open system of Creative Inquiry with active, engaged, ongoing learning, wonder, and discovery pair with the application of defined standards of thinking and elements of reasoning as we develop intellectual traits, or critical thinking, to form a new approach that is rich with context, open to new experiences, tolerant of ambiguity, and synergistic.

A CREATIVE CRITICALITY: A SYMBIOTIC APPROACH

In this approach, I fuse Creative Inquiry with critical thinking (as elucidated by Paul and Elder) to produce a Creative Criticality that provides a greater likelihood for students to achieve the intellectual traits we described earlier but at least four of which Creative Inquirers are already explicitly pursuing (intellectual curiosity, intellectual courage, intellectual perseverance, and independent thinking). I do not suggest that Creative Inquiry is superior to critical thinking, rather they are enmeshed and intertwined in eminently compatible ways that have been hidden, disguised, and denied in the current version of the Reproductive Education system and now need to be freed to act in the symbiotic way they are organically suited. As we work to demystify creativity and revisit the possibilities in creative thinking we enhance our ability to innovate, minimize bias, contextualize, and produce knowledge.

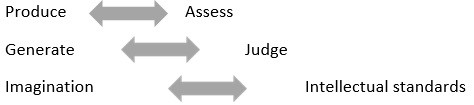

Creative Criticality contains within it a paradoxical image problem that is culturally-based. When the word “creative” is heard we automatically think of the lone genius, the tortured artist, or the oddball. When we hear the word “critical” we think of skeptical, overly harsh, or judgmental. In both cases, the implications are skewed despite their fundamentally positive intentions. A Creative Criticality then, while comprised of two dichotomous and image-laden concepts, are achievements of thought with creativity suggesting production or making and criticality assessing and judging. As observed by Paul and Elder (2008),

“When engaged in high quality thought the mind must simultaneously produce and assess, both generate and judge the product it fabricates. In short, sound thinking requires both imagination and intellectual standards…intellectual discipline and rigor are at home with originality and productivity…these supposed poles of thinking (critical and creative thought) are inseparable aspects of excellence of thought.

The interdependent nature of a Creative Criticality is couched within systems of meaning that we tend to assign thoughts and ideas. Humans think best as systems thinkers where meanings become associated with clusters of meaning. The trick is to teach people to think for a reason, to think purposefully and systematically with assessments of those systems ongoing and in accordance with criticality. The open, living system of Creative Inquiry we explored earlier now comes into focus as a dynamic partner for criticality.

IMPLEMENTATION

Introducing a Creative Criticality requires some degree of finesse and perseverance as it is far easier to retreat to the comfortable status quo of linear thinking on the part of faculty and students. To counter this natural human impulse for the comfortable and familiar it is imperative that we be able to demonstrate the immediate value, worth, and importance of critical creative thinking. In the types of online programs that I am experienced in there are typically one or more structural courses introducing the program, its goals and expectations, and generally acclimating the student to the feel of graduate-level academic work. Such courses are perfect opportunities to build-in introductions to critical creative thinking and help students connect with the Elements of Reasoning, the Standards of Thinking, and the logic of the discipline. I suggest a variety of approaches including visual, practical, and written to appeal to different learning styles. There are several key areas that instructors should return to frequently as the course unfolds to reinforce the fundamentals of critical creative thinking:

- Critical creative thinking should be a lifelong process of self-monitoring and self-correcting our thinking. Thinking underlies all activities, choices, and decisions in life and will contribute to our happiness, success, and fairmindedness when it is done well.

- Creative thinking creates ideas, concepts, and options, while criticality evaluates, assesses, and judges those options. They are synergistic and intertwined; creative thinking allows criticality to push concepts and ideas further than would be possible otherwise.

- The Elements of Reasoning and Standards of Thinking may be used to assess our thinking, and the thinking of others, to read critically, write critically, listen and speak critically. Using the Elements and Standards should become second nature as a basic check mechanism to ensure our thinking is sound.

- Everyone has bias’, prejudices, and a point of view. Similarly, it is human nature to engage in egocentric and sociocentric thinking; the challenge is to acknowledge and minimize their effects on fair-minded thinking.

- All people are creative. We only need to slow down, open ourselves to new possibilities, and tolerate some ambiguity to generate new and interesting alternatives. Giving ourselves permission to be creative is essential to developing as critical creative thinkers.

Students in graduate programs may come from a variety of backgrounds. Some will be from creative areas while others will be from “concrete” fields. The challenge is to raise the level of conscious awareness regarding the utility of a creative criticality. I have found that students, once exposed to these concepts on a continual basis, will quickly respond as they begin to assess their thinking and the thinking of others in the classroom and beyond. The Paul-Elder approach is an extremely powerful, yet flexible tool to implement in our lives to improve student’s thinking and actions. Most educators today have noticed the decline in overall writing skills; I submit that the mechanics of writing are one aspect but not the most important aspect. Effective critical creative processes need to be in place before students write, during, even after an essay or other written work is complete. Simply put: thinking comes before the writing therefore we need to improve the thinking to improve the writing.

Ways to embed critical creative thinking in online courses include:

- Designing written assignments that ask deeper questions of students. Students must be engaged to move beyond surface level recall of facts or opinions to uncover nuance, subtleties, and deeper meanings.

- Utilize concept maps and mind maps as visual tools to aid students in not only conceptualizing associated complexities but also to arrive at questions worthy of their explorations.

- Encouraging students to take creative risks by providing the freedom to explore, investigate, and engage by creating a course space that is supportive and nurturing of this attitude toward scholarship.

- Interacting with students in ways that continually reinforce the necessity of developing a lifelong practice of critical creative thinking. When students ask for our opinions we should encourage them to self-assess first using the Standards of Thinking. Most questions can be answered by students self-assessing their own work.

- Repetition of key aspects of the Paulian model such as the Standards of Thinking and Elements of Reasoning in course design reinforces to students that we are committed and serious about our dedication to this approach.

By no means is this list exhaustive; there are likely numerous ways for instructors to challenge students to think about their thinking and the thinking of others in discipline-specific modalities.

The biggest gains will be seen when instructors can provide those Aha! moments where students suddenly understand that creative thinking is more than producing an artistic product or critical thinking encompasses a way of thinking and being that applies directly to their coursework, their careers, and their personal lives. When we can make those experiences happen for students we set them on the path toward embodying a creative criticality.

There are always considerations we must take into account when implementing any new approach but with critical creative thinking it is likely that administrators in higher education will find that most of their stated programmatic outcomes involve, or are already predicated on, a robust critical thinking approach. Implementing the Paul-Elder approach involves educating faculty to understand how they can seamlessly weave the Standards of Thinking and other aspects into their curriculum. Some instructors will be very supportive while others will receive it with stony silence (probably considering how much extra time this may cost them in course design and/or delivery). Instructors should never be forced to implement a creative criticality because if the passion for improving thinking is not inherent in the instructor the result will be forced and fail to inspire students to embrace a lifelong practice of self-monitored, self-corrective thought.

EVALUATION

It might be tempting at this point to think that implementing the Paul-Elder approach will magically improve student performance, but the reality is we can only introduce the concepts and demonstrate how Dr. Paul’s model finds utility in our work and lives; students must acquire the content on their own. In that spirit, we provide the tools and enthused, optimistic energy but students will decide on their own how much or how little they will engage with them. There are however some practical considerations we must be aware of such as how we evaluate the effectiveness of the approach for our students.

Students typically respond with increasing enthusiasm for the approach the more they see results in their coursework, in their careers, and in their personal lives. Some of the most poignant student feedback I have received comes from students describing how they now see the world differently with a keener eye for inconsistencies in their thinking and the thinking of others. Students will quickly let you know when the model is working for them and how it is affecting their lives. There are other more concrete ways we can use to assess the effectiveness of the Paul-Elder approach in student work:

- Instructors may explicitly use the Standards of Thinking to evaluate written work by students and provide substantive feedback on where a student falls short on one or more aspects. Ideally, we want students to self-monitor and self-correct their thinking, but we are encouraging it as a lifelong practice where students improve over time; substantive feedback is often the most valued aspect of the student-teacher interaction.

- Including the freedom to use visuals in assignments is a key way we encourage students to think of their work (and themselves) as an open system but evaluating how well they utilize visuals to inform their discussion requires that we use the Standards of Thinking in evaluating the visuals for clarity, relevance, logic, fairness, and other relevant aspects.

- Evaluation of major papers is always challenging for instructors but when students apply the Standards to their thinking and writing we typically see essays that contain better structure, better content, and better thinking. Rubrics may be updated to reflect an emphasis on assessment points contained in the Standards as well as traditional rubric elements. Deciding which points we would like to evaluate depends on the aspects we choose to emphasize to students but in teaching a creative criticality there are several key items we should seek to measure:

- Risk-taking – both creative and intellectual.

- Complexity – in thought and action.

- Curiosity – in alternative directions pursued and overall tone.

- Rigor – in all work.

It is important to keep in mind that improvement on all levels occurs over time. As the process of demystification of creative and critical thinking take place and light bulbs flash in the minds of students denoting realizations, students enter a long growth curve that is easily observable through the course of a student’s graduate career. For students who have been exposed to a creative criticality the gains may be as they are more willing to enter (and be comfortable in) the creative process paired with critical thinking. Critical and creative thinking are mutually dependent and mutually beneficial but when we make that relationship explicit students are encouraged to break through the illusions society has crafted regarding the value of creative thinking. Lastly, the meta-level evaluation we can expect to see is the appearance of intellectual traits as a result of student willingness to push further into unknown and challenging academic domains bolstered by their newfound intellectual traits to guide them in their academic pursuits.

DISCUSSION

The symbiotic relationship between critical and creative thinking is a necessary and complementary engagement with our thinking in ways that mimic the natural process of thinking. In our intensely linear society where the shortest line between two points is often the preferred (though shortsighted) mode of thinking creative thinking is often presumed to occur in the synthesis or application stages of problem solving but typically is never explicitly recognized for its worth or value. Criticality is often viewed as the culturally-approved paradigm that supports an educational system obsessed with testing and scores at the expense of deep understanding, broad application, or innovative solutions to complex problems. The need to empower graduate students with the natural capacities they already possess has never been greater nor has the advantages offered by thought processes steeped in the best of both worlds been more important as the challenges in our increasingly complex world have multiplied exponentially.

It might be tempting to think we can simply infuse our efforts at critical thinking with a framework for thinking creatively but such token attempts fail to take into account the need to fundamentally demystify creativity. What is needed is a robust, energetic model of creative thinking to combine with a conceptualization of criticality as part of a lifelong practice of improving our thinking over time (such as in the Paul-Elder model); we have such an approach in Creative Inquiry where the nature of how we learn is continually open to question with each of us as producers of knowledge and where there is a joy to inquiry when we are able to view such production as part of an open system we come to embody and embrace as higher education professionals.

Similarly, we must view each faculty member’s role in carrying a Creative Criticality as akin to a jazz band where each musician plays a special part with freedom to improvise. Each discipline has a distinct logic or way of making sense of the world; each teacher also has a unique way of interacting with students and communicating the logic of the discipline. Allowing our faculty to explore with critical creative thinking is not only freeing for them but also for the students as well as they witness their teachers taking risks, asking deeper questions of themselves (sometimes with no clear answer), and doing so in a way that exemplifies a way of learning and knowing that integrates the best aspects of thinking and acting critically and creatively.

There are some limitations that are worthy of note; specifically, simplistic problems calling for simplistic answers are not as amenable to thinking deeply. For instance, accounting has very specific rules and requires that one not consider alternatives in entering a number or making a calculation. We would argue, however, that there is another layer to this, such as when a business leader begins to interpret the numbers that have been supplied. Applying the standards of thinking and elements of reasoning would be indispensable in conceptualizing how to interpret, assess, and apply the knowledge gained in generative ways. Simply put: one must choose the most appropriate items from the standards of thinking as they inform the current problem combined with a willingness to engage openly with possibilities.

The ever-increasing complexities and dangers in the world demand of higher education professionals a more sophisticated and nuanced approach to online education that allows students to begin a lifelong practice of critical creative thinking. Demystifying creativity and explicitly recognizing the worth and importance of teaching a Creative Criticality are necessary to counter trends in anti-intellectualism, anti-science, and regressive educational policies designed to control a populace by limiting its inherent ability to think and reason with the innate fluidity humans have used to travel to the moon, develop technologies, and preserve and extend knowledge through untold generations. Though the journey to embedding an effective Creative Criticality program by program is immeasurable it will take each of us doing our small part to set our students on lifelong paths of self-awareness, self-improvement, and self-monitoring, self-corrective thinking in order to effect positive change in our world. As the world continues to become increasingly complex, dangerous, and difficult to navigate our imperative as higher education professionals is to equip students not only with a toolkit that integrates our capacities to innovate and apply but also with a set of intellectual ethics to guide them in making choices for the companies, organizations, and institutions that so directly impact the lives of our citizenry.

CONCLUSION

The ever-increasing complexity of our world brings many challenges and dangers we must approach with complex, high-quality thinking. As higher education professionals tasked with the duty to adequately prepare students for the many challenges in the world we are obligated to move beyond modes of education that do little to impart critical creative thinking as a lifelong practice. To enable others to exhibit empathy and compassion in their thoughts and actions graduate programs, such as the ones I have described, need to focus on helping students develop their lifelong practices of critical creative thinking coupled with fairminded actions and thoughts. Our society sits at a critical juncture of control by egocentric and sociocentric forces that polarize people into various camps of thought and action where the needs of the majority are not met in an ethical way. Students who are prepared to implement a practice of self-monitored, self-corrective thinking in themselves may apply the same standards (which are universal or nearly so) to the thinking of others.

The struggle to impart high quality thinking to our students has never faced greater challenges as the masses of our society continue to face concerted efforts by controlling forces to manipulate and exploit their thoughts, beliefs, and worldviews for ends that serve narrow interests. Students who are educated in such a way as to leave our programs nurturing a nascent critical creative thinking practice are well-equipped to discern the quality of thinking they encounter and to do so in a rational, fairminded way. The true benefit of educating the whole person may be cumulative over time but the results begin to show up in the lives of students almost immediately. Inspiring students to learn what they are capable of in service to themselves, their families and communities, indeed the world should be our goal as we design and carry out graduate online programs on the leading edge of human thought.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. The three threats to creativity. Harvard Business Review 2010. Available from http://blogs.hbr.org/hbsfaculty/2010/11/the-threethreats-to-creativit.html

Bailin, S.; R. Case; J. R. Coombs & L. B. Daniels (1999). Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 285-302.

Cooper, T. (2015). Thrive: The highly sensitive person and career. Ozark, MO: Invictus

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publisher.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. American Philosophical Association, Newark, DE. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 315423)

Florida, R. 2002. The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Florida, R. 2004. America’s looming creativity crisis. Harvard Business Review October:122–136.

Friedman, R. 2009. The new untouchables. The New York Times October, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/21/opinion/21friedman.html?

Gidley, J. (2010). Postformal priorities for postnormal times—A rejoinder to Ziauddin

Sardar. Futures: The Journal of Policy, Planning and Future Studies 42 (6): 625–632.

Jensen, R. 2001. The dream society. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Montuori, A. 1989. Evolutionary competence: Creating the future. Amsterdam: Gieben.

Montuori, A. (2011). Creative inquiry: Confronting the challenges of scholarship in the 21st century. World Futures, Vol. 44, pp. 64-70.

Montuori, A., and Donnelly, G. (2013). Creative inquiry and scholarship: Applications and implications in a doctoral degree. World Futures, Vol. 69, 1-19.

Mueller, J. S., Melwani, S., & Goncalo, J. A. (2011). The bias against creativity: Why people desire but reject creative ideas [Electronic version]. Retrieved [3/20/2018], from Cornell University, ILR School site: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles/450/

Phillips, V. and C. Bond (2004) Undergraduates’ experiences of critical thinking. Higher Education Research & Development, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 277-294.

Pink, D. 2006. A whole new mind. Why right-brainers will rule the future. New York: Riverhead Trade.

Pithers, R. T. and R. Soden(2000). Critical thinking in education: a review. Educational Research, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 237-249.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2004). The thinkers guide to the nature and functions of critical and creative thinking. Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2006). The miniature guide to critical thinking concepts and tools. Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Paul, R. (2007) Critical Thinking in Every Domain of Knowledge and Belief. The 27th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking. The Foundation for Critical Thinking: Dillon Beach, CA.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2008). The thinker’s guide to the nature and functions of critical and creative thinking. The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2014). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your professional and personal life. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Paul, R., Elder, L., & Bartell, T. (1997). California teacher preparation for instruction in critical thinking: Research findings and policy recommendations. The Foundation for Critical Thinking: Dillon Beach, CA.

Robinson, K. 2001. Out of our minds: Learning to be creative. London: Capstone.

Robinson, K. 2009. The element: How finding your passion changes everything. NewYork: Penguin.

Sardar, Z. 2010. Welcome to postnormal times. Futures 42 (5): 435–444.

Seel, N. (2012). Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. New York, NY: Springer

Sumner, W. (1906). Folkways. Boston: Ginn.

About The Author

Tracy Cooper, Ph.D. is Program Chairman of the Master of Liberal Arts program at Baker University School of Professional and Graduate Studies. He holds a Ph.D. from the California Institute of Integral Studies in Transformative Studies (personality psychology) and has taught on-campus and online courses in multiple institutions. Tracy has also provided leadership to the highly sensitive community by appearing in the 2015 documentary Sensitive – The Untold Story and publishing two books: Thrive: The Highly Sensitive Person and Career and Thrill: The High Sensation Seeking Highly Sensitive Person. His most recent work: Attuned Thinking for the Highly Sensitive Person is expected to be released later this year.