Elliot Jaques Revisited

Jan De Visch, The Vertical Dimension. Blueprint to Align Business and Talent Development (Connect & Transform Press, 2010) ISBN 978-94-9069-538-5. Available from http://www.connecttransform.be/

Jan De Visch, The Vertical Dimension. Blueprint to Align Business and Talent Development (Connect & Transform Press, 2010) ISBN 978-94-9069-538-5. Available from http://www.connecttransform.be/

Nick Shannon

At first sight this is not a book about leaders or leadership. It is a book about organizational development setting out a theory of the thinking and processes that lead to organizational success. And, whilst not explicitly aimed at business, the focus is very much on organizations that intend to provide a financial return for shareholders—in other words, organizations that have a mandate to create shareholder value. However, the author takes what is essentially an “integral” perspective in that he critiques current approaches to talent management that treat it as an isolated discipline separate from other organizational systems. In essence, he advocates an integrated approach that aligns business strategy, organizational structure, and development of human resources.

Treading in the footsteps of Elliot Jaques, De Visch’s blueprint involves structuring managerial accountability in hierarchical layers and matching the capability of managers with the complexity of responsibility that they might encounter at the particular layer in which their role sits. Matching the “size of person” with the “size of role” is itself a controversial and often complex process, yet De Visch argues firmly that leadership is, in effect, grounded in the management of complexity and that the improvement of organizational performance is a matter of “allocating decisions to those staff best able to take them and developing them so they can cope with the appropriate level of complexity in their roles”.

A professor of HRM at Flanders Business School (Belgium) and an organizational development consultant, Jan De Visch sets out four stories or case studies that describe his theory from four different perspectives. Of interest to CEOs, business and HR managers, as well as other consultants, each story, encapsulated in a single chapter, covers similar territory but with a slightly different emphasis to demonstrate how organizational performance can be improved by putting an understanding of human capability at the centre of decisions about organizational structure and strategy. Readers should be warned that there is considerable overlap in the ground covered by each chapter that might best be described as telling the same story four different ways. That said, the benefit of the format is that it allows the reader to dip in and out, to get a quick sense of the whole, and to select passages of most relevance and interest. This is, perhaps, not a book that one might want to absorb from cover to cover on a mid to long-haul flight.

Written from a consultant’s perspective and in a consultant’s language, the book’s style is intended as a practical source of discussable ideas rather than an academic thesis. Whilst seemingly drawn from the author’s personal experience, the case studies are written in anecdotal form and few details about the actual businesses are given. Hence, it cannot be argued that there is a solid base of academic research to underpin De Visch’s prescriptions. Instead, he provides ideas and concepts for the reader to test for him/herself. And he has been generous in doing so, since he has abandoned copyright issues by offering the book with “no rights reserved”. De Visch is also magnanimous in his credits, citing the work of Otto Laske and Mark van Clieaf, as well as Jaques and many others as his inspiration. Although some business leaders and practitioners might baulk at the experimentation proposed, there is much good sense in what is offered here, and much that one can argue is well supported by evidence from successful organizations that practice versions of Jaques’ “Requisite Organization (RO)” or “Stratified Systems (SS)” principles. Of course, Jaques’ theories are not without their critics and still have a relatively limited following despite relatively strong scientific validation.[i]

For the sake of clarification, I should briefly summarize the key points of Jaques’ general theory of managerial hierarchy (as he later renamed RO & SS). From his observations of large organizations, Jaques postulated that people naturally organize themselves into hierarchical layers or strata in order to get work done. This organizing principle, whether conscious or not, lies in the problem-solving capabilities of the individuals themselves. Such capabilities also fall into discrete layers governed by the ability to process information of different orders of complexity. For example, a CEO might be positioned at stratum 6 or 7, whilst a first line manager might be positioned at stratum 1. This natural organization, is according to Jaques, mutually rewarding for those at any level of the hierarchy, and for the organization itself. Specifically, the relationship between a manager and his or her subordinate will be perceived by each party to be satisfactory if their respective capabilities and the work that they do is one order of complexity apart.

Jaques further postulated that all manner of organizational problems and inefficiencies arise if the natural order of capabilities and their match with the complexity of work are not followed. For example, if a manager’s capability is at the same strata or below that of his subordinate, then that subordinate will not feel properly managed and may well perceive the pay differential between the two of them to be unfair. Hence, “leadership” for Jaques is a function of organization and the relative capabilities of leader and led, as opposed to being related to specific competencies or characteristics of the leader.

Jaques devised a means to measure both an individual’s capability and the complexity of a role based on what he termed the “time span of discretion”. This refers to the time taken to complete the longest task set for a particular role. For example, an engineering project manager might be given a project that would take three years to complete; a corporate vice-president might be asked to start and establish a regional business over five years. In practice this aspect of Jaques’ theory causes confusion and difficulty because managerial tasks are not always clearly defined or delineated in terms of time. It is also not clear that complexity is necessarily linearly related to time. For instance, volatility in markets and rapid changes in technology create considerable complexity for some organizations over very short timescales; look at the ever-changing leadership of the cell-phone market for example.

The measurement of an individual’s capability is therefore also problematic if defined solely in temporal terms. One might legitimately claim that an individual accomplishing a very complex task within a short time frame was more capable than one accomplishing a less complex task over a much longer-time frame. In fact, Jaques suggested at least two independent methods to establish a person’s capability. One took the form of an interview in which the thinking processes of the person are analyzed; the other was simply to ask the person’s manager and manager’s manager (manager once removed—MOR) if the person was currently capable of working at a higher level. But it is hard to see how this latter method might work in any organization that was not already applying Jaques’ ideas.

The challenge, then, for supporters of Jaques’ theory has been to elaborate a more convincing method of measuring role complexity on the one hand, and individual capability on the other. And this is what De Visch sets out to do, drawing on the work of VanClieaf and Laske, respectively, with the overall aim of showing how the currently popular concept of “Talent Management” can be connected to the determination of business strategy and organizational structure. This is an important step, since for many organizations talent management is treated as a peripheral activity—something that HR professionals are tasked to work out how to do only after their operational masters have decided where the organization is going to go and how it is to be structured.

First, De Visch develops the notion of the “size of role” by reference to what he calls the “added value” of the role. Here the term “added value” refers to the product of the decisions involved in carrying out tasks. One imagines that De Visch sees decisions resulting in certain outcomes, the value of which can be quantified. However, his definition feels somewhat unsatisfactory since he does not make it clear how one might measure such value, nor is it clear exactly what tasks a particular role might involve. Ultimately, De Visch seems to get around this problem by specifying the kind of work that he expects to be carried out at different levels of organization (Table 1), but without spelling out why he sees work at progressively higher levels adding incrementally more value. We have to assume, for example, that the “global governance” role he posits at the top level (7) of his hierarchy necessarily adds more value than the role of “creating new business models”, which he puts at level 5. Such an assumption should not be taken for granted. By illustration, would you say that Mark Zuckerberg (founder of Facebook) creates more or less value than his venture capital backers? And should a highly successful trader earn more than the CEO of his company, as can be the case? It is therefore not clear that this link between hierarchically increasing “size of role”, task complexity and added value is true for all situations.

Table 1: The added value framework (De Visch)

| Size of roles | Size of persons |

| Level 7 : Global governance | Level 7 : Global governance response: whole business systems’ viability is frame of reference. Holistic societal-integrative systems thinking provides the framework for decision making. |

| Level 6 : Governance & business portfolio | Level 6 : Governance/business portfolio response: multiple systems synergy creation, meta-rule making and global systems transformation. |

| Level 5 : New business model, reshaping relative competitive position | Level 5 : Comprehensive response: Holistic business-integrative systems thinking provides the framework for decision making. New rules are created. |

| Level 4 : Creating breakthroughs, reshaping profitability | Level 4 : Breakthrough response: complex system mapping frame of reference. Multiple contexts, emerging changes and abstract modeling provide the framework for decision making. Rules are changed. |

| Level 3 : Rethinking operational flows & value streams | Level 3 : Integrated response: systemic, team-team, re-engineering frame of reference. Rule extrapolation and decision making based on probing and redefining (linear/circular) relationships. |

| Level 2 : Service differentiation and optimization | Level 2 : Situational/diagnostic response: conditional, diagnostic (through analyzing causes and responding), effectiveness-focused and rule-bound decision making. |

| Level 1 : Quality and service delivery | Level 1 : Procedural response: practical, common-sense, rule-based and procedural decision making (categorizing and responding). |

Secondly, De Visch develops the notion of “size of person” with reference to two developmental “lines”: the “cognitive” and the “social-emotional”. Here, he draws on the work of Laske[ii] in asserting that the decision-making capability of a person in a role (and by consequence their ability to add value) is a function of their level of development, both in terms of the “tools” they possess, by which he means their cognitive thinking skills, and their social-emotional “stance”, by which he means their ability to apply such thinking skills by making decisions. Whilst Laske has described in detail two kinds of semi-structured interviews (Cognitive and Social Emotional) and a scoring system to assess developmental levels, De Visch has developed an alternative method for assessing the “size of person” called “DESTINY”. This method invites the participant to describe his role in terms of various competencies such as “Defining Vision and Objectives/Shaping Strategic Direction”. For each competency, the interviewer selects cards summarizing how that competency might be demonstrated at two adjacent levels of hierarchy, and asks the participant to select the one that best summarizes the way he sees his work. Initially, the interviewer makes an informed guess at the level that is likely to be most appropriate, but once the participant has selected the most appropriate card, the interviewer asks questions designed to probe the kind of thinking tools that the participant is using and his social-emotional level. Since personal experience has shown that Laske’s interview process can be complex and arduous to operate in practice, this innovation may be of interest to assessment practitioners. However, details of its exact form and reliability and validity data are not provided in the book and direct comparisons with Laske and Jaques’ methods are not possible since such data is not available for them, either.

It should be said here that the main aim of the book is to put forward a way of thinking about the inter-relationships between the people development and the business development aspects of an organization, not to critique De Visch’s fore-runners and sources of inspiration or to put forward a new assessment methodology. Three of De Visch’s four case studies are written as dialogues between a consultant (Ian) and senior managers of different organizations that are wrestling with particular problems. De Visch invites his readers to choose the story that resonates most strongly with them in the hope that, by reading the exchange of ideas between manager and consultant, readers might gain some insights as to how to deal with their own situations.

Each case study occupies a chapter of the book and the nine key ideas presented are usefully summarized in a fifth and final chapter. The first chapter sets out De Visch’s analysis of the different levels of work complexity and the factors that need to be considered when assessing the complexity of a role. The emphasis here is on identifying the different types of work required in an organization and mapping these to the appropriate level so that the required number and spread of managerial levels can be determined. Once analyzed in this way, an organization can set about deciding whether it has managers with the appropriate capability at each level. Different organizations will have different numbers of levels depending on the nature and extent of their activities. As Jaques indicated, a poor organizational design will have roles that are misaligned with the number of levels required, thus creating crowding or gaps in the structure, leading to ineffective leadership. De Visch highlights what he considers to be a number of other risks associated with poor design, for example, reward structures may be out of alignment in terms of the differentials between levels or the time span of roles. A manager might, for example, receive 90% of his compensation based on current year results when the role he occupies has accountability for results in a much longer timescale. The chapter concludes with a brief debate about the nature of short and long-term value creation. De Visch sees accountability at the lower 3 or 4 levels being optimally targeted at current value creation i.e. this year’s results, and accountability at higher levels being targeted at future years results.

Chapter 2 tells the story of a retail business coming to terms with a downturn in business. The general thrust of the chapter is to show how, firstly (and overlapping with chapter 1) the managerial structure can be improved, and secondly, how the quality of strategic debate can be increased. In large part a dialogue between De Visch’s alter-ego consultant, Ian, and the executive management, three key concepts are explored. The consultant proposes the restructuring of the management hierarchy according to Requisite Organization principles, and shows how a more formal management structure could be supplemented using Brian Robertson’s concept of linking holocracies[iii]. De Visch then goes on to describe how the use of Laske’s dialectical thought forms could enhance the management team’s debate about strategy. The chapter concludes with a brief overview of the consultant’s proposal for a series of workshops to develop the new strategy, restructure the company and develop the capability of staff to suit the new structure. In epilogue, a short letter from the CEO written a year later describes the successful turnaround of the business.

Chapter 3 emphasizes the value of linking business strategy with talent management through the story of a manager (Bart Jenkins) whose organization put him into a role above his head through failure to assess correctly both the challenge of his new role and his level of capability. Here De Visch expands the concept of the “Size of Person” and its cognitive and social-emotional components in more detail, and describes the DESTINY system of assessment. Cognitive development is defined in terms of a persons’ progress through stages of logical thinking to “dialectical” thinking (Laske 2008), and social-emotional development is seen in terms of progression through the stages of Robert Kegan’s subject-object model[iv].

Whilst the detail of the 28 different thought forms that constitute the notion of “dialectical” thinking may be a step too far for the casual business reader, their inclusion is important in order to start putting some flesh on the bones of what some writers contend are key leadership competencies—“vision, integrative thinking, intuition, holistic thinking”—but which are usually vaguely and incompletely spelled out. Of particular interest is the last part of the chapter describing the concept of “growth assignments”. A difficulty with Jaques’ model is that he placed a very deterministic slant on the development of peoples’ capability by positing that growth follows a natural curve over time. This effectively enabled him to make a prediction of an individual’s ultimate potential from a measurement of their current capability at a certain age, but left the impression that potential was fixed and impossible to influence, rendering development action limited in scope. By contrast, De Visch suggests that an individual’s development can be facilitated using growth assignments, which are effectively work experiences at one level of complexity above the one at which the person is currently working, facilitated by a more senior manager. De Visch sees the task here as one of enabling the individual to develop “thinking structures” appropriate to the next level of complexity through giving them a taste of higher level work. This creates a responsibility on the organization to assess correctly the level at which staff are currently working and on more senior management to redesign work roles so that appropriate opportunities are forthcoming. Development is therefore taken “in house” and the use of external courses, coaching and mentoring are provided only to support the process.

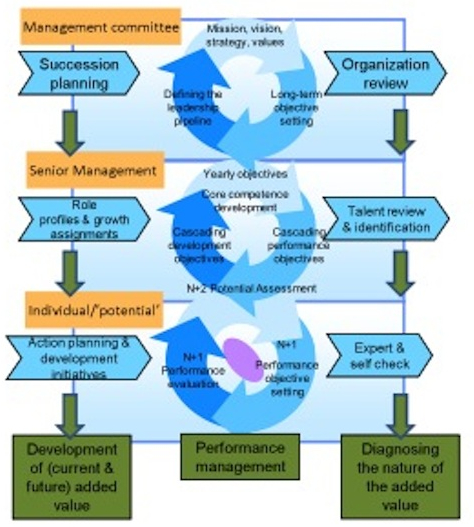

The final case study in the fourth chapter provides the opportunity for De Visch to reveal his talent management system (Diagram 1). In this case study the consultant, Ian, takes his client—the management of a publishing company—through his thinking on how they should revise their talent management processes in the context of a business need to switch product platforms from the traditional book to on-line media. Ian begins by critiquing the current system for its focus on succession (positioning people to take up existing roles) instead of a focus on developing people for higher levels of accountability. He suggests that the management should switch from a mental framework that decides what talent management processes to adopt on the basis of what is perceived as industry “best practice” to his, more theoretical, framework based on developing overall organizational capability. This links to what he later expresses as the main aim of development—to shift a person’s “personal knowledge system” to a higher level. Here he borrows a term from Roger Martin’s book “The Opposable Mind[v]”. A personal knowledge system combines “stance”—one’s sense of purpose and meaning, “tools”—the mental models one uses to understand the world, and experience. De Visch sees leadership development being aimed at facilitating a shift towards higher levels of stance and tools, through appropriate experiences and guided reflection (assisted by more senior managers). Formal leadership development must therefore be based firstly on an assessment of a person’s current “personal knowledge system”, then on appropriate role design and support.

Diagram 1: The integrated talent management system (De Visch)

So De Visch’s recipe for an integrated talent management system ultimately consists of 3 elements:

- Action from top management to set the context for organizational development. Ultimately this means determining the structure necessary to carry out the company’s strategy, setting the number of management levels and the accountabilities at each level, and ensuring that there is a match between the size of person and the size of role.

- Action from senior management to specify tasks necessary at each level to carry out the accountability associated with that level, and to design growth assignments that give people the necessary experience to advance to the next higher level. In practice this may mean upgrading existing competency models to reflect more accurately the differences between levels.

- Action from individuals throughout the organization to build their own self-awareness, with the assistance of their manager-once-removed.

The paradox of all of this advice is that, in as much as De Visch is critical of what is currently considered best practice (“best practice is past practice” Ian says), ultimately he has offered us a view of what better practice might look like without producing the evidence that it necessarily leads to better organizational performance. And, if De Visch’s ideas eventually become best practice, inevitably they, too, one day will become past practice, as well. Equally, it is unlikely that Elliot Jaques would have approved of all De Visch’s thinking since he was adamant in the use of time-span measurement as the determining factor of the level of work, while De Visch suggests several other measures to capture the complexity of a role, but seemingly without the depth of research that Jaques applied. However, by combining the ideas of several theorists, De Visch has produced what could be seen as a pragmatic approach to some of the criticisms of Jaques’ ideas whilst bringing more recent work on the nature of adult development into the equation.

Interestingly, the “Vertical Dimension” reveals, between the lines, something of the way management consultants work with their clients. In essence, the approach is based on using an organizational “problem” to provide a diagnosis and a critique of the thinking that led to that “problem”, coupled with the offer of a new model and way of thinking that takes the client into a new pattern of action. The new model is rarely “proven” in the same way as a scientific theory might be proven, but is adopted (or not) on the basis of the consultants’ ability to persuade their clients to their way of thinking. The developmental model that De Visch introduces suggests that human thinking is inherently limited, at different stages, by limitations in the “tools” and “stance” that define the perspective on the world that an individual can take. By implication, De Visch’s model will be of interest to some, but not all, organizations, however effective it might prove to be for his own clients, since some will not be ready to take the perspective that he advocates. A number of general questions are also relevant here:

- Do the principles work well for all organizations, or just for large corporates?

- How do political and cultural factors enhance or dilute the adoption and effectiveness of such principles?

- How do shareholders’ expectations of investment returns impact on the behaviour of companies to support or inhibit the adoption of such ideas?

- Is it practically possible to specify accountabilities or to measure capability as accurately as might be necessary?

Despite these unanswered questions, one of the main lessons of the book is that the performance of organizations might be well enhanced by a greater focus on the thinking structures employed by participants in debates about business strategy and systems. Much as Mitroff and Linstone[vi] see “paradigm breaking” as a process of surfacing and challenging key assumptions, so surfacing the mental models and perspectives of managers gives us insight into why they think in the way they do, what they are capable of, how they might be helped to develop their capability and how best they might be organized within a management structure in pursuit of a strategic objective.

The Vertical Dimension is self-published and suffers from not having an independent publisher to critique and edit the text rigorously. De Visch is not a native English speaker and, as a result, the book does not always read smoothly. I often felt I had a general grasp of what he was intending, but was unclear about his exact meaning given a tendency on his part to construct sentences with several “business-speak” abstract concepts strung together. De Visch does not spoon feed his readers. More accurately he ladles it at them from all directions, so the book makes a dense and challenging read. But these niggles apart, The Vertical Dimension is a valiant attempt to update Jaques’ theories and bring them to a wider audience in a practical form. Few people would argue that talent development should not be aligned with business strategy, but the devil is in the detail of execution as to how this can be done. De Visch hasn’t quite given us chapter and verse on how to create an aligned talent management system but he has given us a way of thinking and shown that there are some clear unifying principles that will help organizational leaders think through how best to proceed. This integrated theory of how an organization can make best use of its human capital is something about which leaders need to be aware.

Notes

[i] Ivanovov, S “Investigating the Optimum Manager-Subordinate Relationship of a Discontinuity Theory of Managerial Organizations: an Exploratory Study of a General Theory of Managerial Hierarchy” Doctoral dissertation 2006

[ii] Laske, O “Measuring Hidden Dimensions of Human Systems” IDM press. Vol 1 (2006) and vol 2 (2008)

[iii] Robertson, B J. “Organization Evolved: introducing Holocracy” from www.holocracy.org 2009

[iv] Kegan R “The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development” Harvard University Press 1982

[v] Martin, R “The Opposable Mind” Harvard Business School Press 2007

[vi] Mitroff, I & Linstone, H “The Unbounded Mind” Oxford University Press 2003

About the Author

Nick Shannon, UK Bureau Chief for ILR, is the founder and principal of Management Psychology Limited, a UK based practice specializing in organizational and management development. Nick is a Chartered Psychologist, a member of the British Psychological Society and a founding member of the Association of Business Psychologists. After studying Psychology and Philosophy at Oxford University, Nick’s career has involved working variously as a commodity and derivatives trader, a director of a foreign exchange business, and a restaurateur. Latterly a business consultant, Nick’s goal in working with clients is to help them improve the quality of their management teams, which he believes leads to better organizational performance and more satisfied and engaged employees. Typical assignments involve the design and delivery of assessment, selection and development processes at three points of focus: individual leaders; senior management teams; and organization-wide.