How Organizational Archetypes Manifest at Each Level of the Gravesian Value Systems

Jorge Taborga

Abstract

Organizational culture provides the impetus for the behaviors in an organization which work to fulfill its mission or work against it. Schein (2010) stratifies culture into artifacts, values and beliefs, and underlying assumptions. The latter are the deeper and unexamined values that contain the models of behavior resulting from the shared experiences of the organization as it solves problems and which are taught to all its members. According to Jungian organizational depth psychology, as documented by Corlette & Pearson (2003), these underlying assumptions reside in the unconscious of an organization, particularly in the part of the its psyche called “complexes.” These complexes are formed through organizational experiences patterned by the psychic energy of archetypes as they take form through the minds of individuals and collectives.

Dr. Clare Graves spent most of his professional life researching and ultimately developing theories for the value systems that associate different life conditions with the mental capacities that emerge in humans as they solve problems (Lee, 2009). He named his research the Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theories (ECLET). His theories have been popularized by Beck & Cowan (1996) in their work of Spiral Dynamics. Cowan & Todorovic (2000) equate the Gravesian value systems to the underlying assumptions inside an organization which are largely responsible for organizational cultures.

This essay explores the connections between archetypes and the value systems of an organization as a way to arrive at a deeper understanding of the emergence of organizational culture. Each archetype is explored as a pattern of behavior at each level of the ECLET value systems. An archetypal correspondence map is articulated for three of the most common Gravesian value systems found in modern and post-modern organizations. This correspondence is validated through a case study of a small consulting company. The case study provides a framework for the analysis on how archetypes are manifested in an organization and how the emerging culture can be interpreted through the lens of value systems.

The correspondence of archetypes to values systems explored here provides an approach to a deeper understanding of the emergence of organizational culture. As presented in this essay, this approach is far from being a repeatable method of cultural assessment and much less for intervention. However, it is a start to further research which has the potential for shining light into the organizational unconscious and in particular into the effects that archetypes have on underlying assumptions (value systems). This new light could emerge as a way to assess organizational culture and to determine interventions that would bring culture into greater alignment with the fulfillment of the organization’s mission.

Introduction

Organizations are complex entities, both socially and psychologically. There is also a broad biological element given the neurology of the diversity of humans involved. This bio-psycho-social milieu makes each organization unique, yet they all seem to operate following common patterns of behavior. Strategic plans, Management by Objectives (MBOs), career development plans, performance reviews, budgets, project plans, employee meetings and a host of other practices can be found across most enterprises. Teamwork, consensus, entrepreneurship, bureaucracy, power play, gossiping, scapegoating, and back-stabbing are also behaviors that reside in the depths of organizations and either help or hinder their missions, and either uplift the humans in these organizations or oppress them.

Schein (2010) posits that the culture of an organization determines its actions. He defines culture as:

A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems. (p. 18)

This definition by Schein corresponds to two concepts that will be used throughout this essay: life conditions and mental capacities. These concepts were introduced by the research of Dr. Clare W. Graves and are documented in the book The Never Ending Quest (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). Dr. Graves developed what he called Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory (ECLET). In this theory, humans are exposed to a variety of life conditions (Schein’s problems) which give way to mental capacities to solve them (Schein’s basic assumptions). In Graves’ theory, human development can be grouped into value systems that are in agreement with what has “worked well to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members” (Schein, 2010, p. 18). This is the culture or the value systems of individuals in an organization or a much larger social system like a country or a particular ethnicity.

Schein (2010) describes culture in three layers: artifacts, values and beliefs, and underlying assumptions. The artifacts are the physical manifestations that tell how the organization is conducting its affairs. Artifacts would include a company’s P&L, its products and services, its workplaces, the pictures on the walls, the types of cups used for coffee, and the t-shirts sporting a catchy slogan given to employees after a product launch. Artifacts are the focus of cultural archeology. Much can be interpreted from their analysis but only superficial theories can be derived about the behaviors of the humans in the organization.

In contrast, value and beliefs correspond to a deeper level of culture. It is the set of shared learning and experiences by an organization. It started with the leader and then became a shared experience. As values are repeated in solving problems, they take on the flavor of underlying assumptions. These assumptions become the internal, reflective muscle of how individuals inside an organization are not only expected to behave but are perpetuated by every action. Even though organizations have a relatively transient population with each member bringing their own set of underlying assumptions, organizational culture normalizes each into a shared set that defines how the organization responds to the problems it faces every day.

Graves studied underlying assumptions starting in the 1950’s through his death in 1986 (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). He leveraged his students and their lives to capture the data necessary for his research. Graves did not start with a theory about the emergent levels of existence (how individuals cope with problems) rather he let the collected data generate a theory. His research started as he wrestled with questions from his psychology students at Union College in New York on which theory of human psychology was correct. He taught a psychology survey class which introduced students to a variety of theories, from Freud’s to Maslow’s.

Graves’ research was simple in structure. He asked each student to write a short essay describing the mature adult personality in operation. After collecting a large number of these essays (he reportedly ended up with about 40,000 of them in a 30 year span), he started to notice patterns in the essays that corresponded to similar descriptions of life conditions (problems for the mature adult) and mental capacities (how the mature adult is supposed to respond to them). He grouped the similar responses into clusters, which gave way to the 8 value systems in ECELT. This theory was popularized by Beck & Cowan’s book Spiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadership and change (1996). Incidentally, both Beck and Cowan worked with Dr. Graves and have continued his work both in application and teaching.

Corlett & Pearson introduced a framework for the organizational psyche in their book Mapping the Organizational Psyche: A Jungian theory of organizational dynamics and change (2003). This work focuses on the interaction of the organizational unconscious and its conscious components through the structures of the organizational psyche. Corlett & Pearson draw a parallel of the organizational psyche from the human psyche as defined by psychologist Carl Jung. This famed psychologist did not focus his attention on organizations because he believed that the organizations of his time (he died in 1961) did very little to emancipate and support human evolution to a state of wholeness (Corlett & Person, 2003). The authors of Mapping the Organizational Psyche undertook this work in response to the new Jungians who felt the need for the application of Jung’s intricate theories of the psyche to various groupings of humans.

Corlett & Person (2003) state that:

Jungian Organizational Theory shares the belief that the question of meaning—why organization members are willing to invest so much of their creativity and agency in organizations—is bound up by the collectively held values at the heart of an organization’s culture. (p. xiv)

These authors further posit that meaning is deeply connected to the unconscious of an organization, which represents the unseen psychic forces that “bind people to each other and their work” (Corlett & Pearson, 2003, p. xiv). Further, Corlett & Pearson hypothesize that the unconscious is the container for the organization’s behaviors and norms that get transmitted to newcomers. The organizational unconscious is also responsible for the collective dynamics or culture. These theories by Corlett & Person are consistent with Schein’s views of organizational culture.

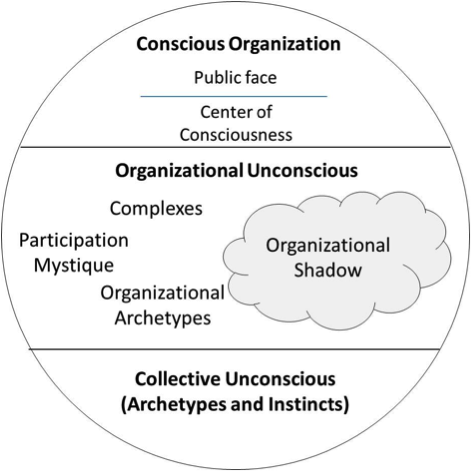

At the root of the organizational unconscious, Corlett & Pearson identify the organizational archetypes. These authors state that along with several other scholars, they view “that the human inclination to create organizations is the expression of an archetype” (Corlett & Pearson, 2003, p.18). They further explain that archetypes are the templates of organizations and that they are the primary vehicles through which the unconscious speaks to an organization to develop toward wholeness. Corlett & Person introduce twelve organizational archetypes arranged in four Life Forces. The first life force focuses on the development of people through relatedness, how the organization relates to employees and how they relate to each other. The second life force provides the template and psychic energy for obtaining results. Learning is the third life force containing the archetypes on how the organization learns, takes risks, and goes about the creative process. This life force is balanced by a fourth, stabilizing. This latter life force brings the structures, processes and systems into the organization to pattern its efficiencies, manifest its creativity and provide for the needs of its people.

This essay aims to establish a correspondence of the organizational archetypes and the ECLET value systems. Based on the theories of organizational culture of Schein, Graves, and Corlett & Pearson, the unconscious, and thus archetypes, are intricately involved in defining the value systems of an organization that are the foundation for the underlying assumptions: the set of problems and the set of known and valued responses in each organization. A case study is utilized to illustrate how the correspondence of organizational archetypes with the ECLET value systems provides a richer and more actionable understanding of an organization’s culture.

Based on his research on organizational culture, the author believes that much of an organization’s operation is tied to its unconscious and the layer of underlying assumptions. These two important components of the organizational psyche deeply affect the successes and failures of an organization. They also provide the bio-psycho-social container for individuals in organizations and affect their own personal development and happiness. If wholeness is the ultimate goal for individuals and by extension organizations, then a deeper understanding about how organizational archetypes and value systems interplay is warranted. This essay is meant to provide a survey of these topics and open up possibilities for further research.

Corlett and Pearson’s Organizational Archetypes

Organizational Psyche

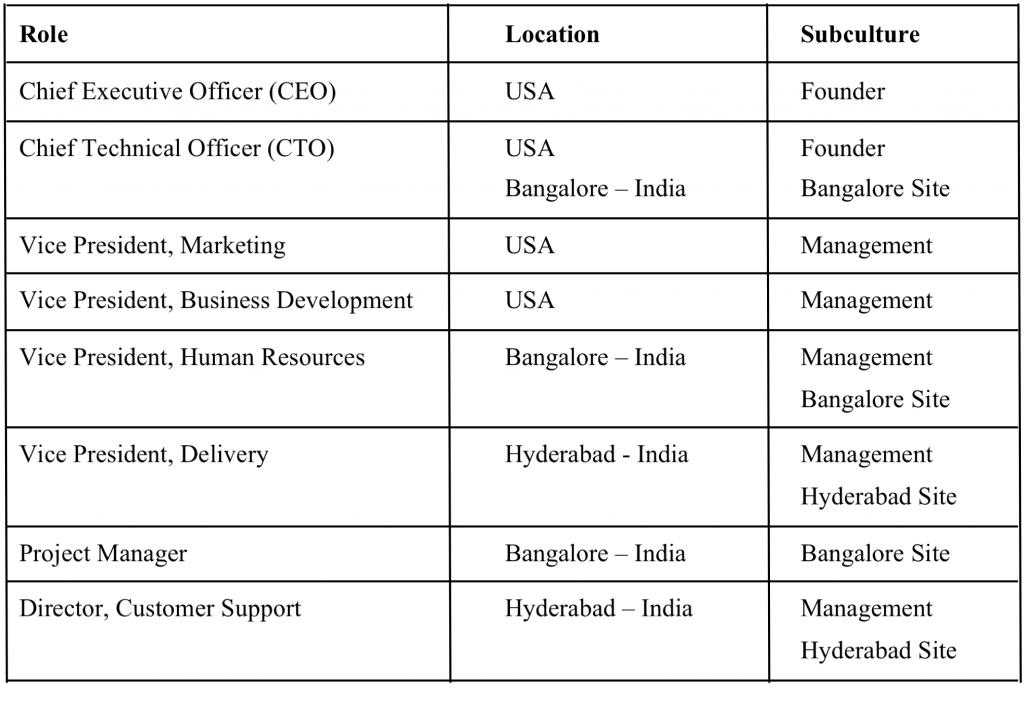

Corlett & Pearson (2003) model the organizational psyche in two layers: conscious and unconscious. In their conception, the conscious layer is where the ego-driven actions and behaviors of those leading the organization manifest activity and shape its culture. The conscious layer is the world of Schein’s artifacts. The unconscious layer, at the heart of psychologist Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, provides the psychic energy necessary for conscious actions. Figure 1 shows the structures of the organizational conscious and unconscious which parallel what Jung conceived as the architecture of the individual psyche. Corlett & Pearson adapted this model and introduced constructs unique to the psychology of organizations.

Figure 1. Map of the organizational psyche. This picture is an adaptation of the organizational psyche by Corlett & Pearson (2003).

Conscious Organization

Figure 1 shows that the conscious portion of the organization is composed on the Center of Consciousness and the Public Face. The center of consciousness is “analogous to Jung’s concept of the ego” (Corlett & Pearson, 2003, p. 27). It comprises all of the conscious activities performed in an organization, such as planning, managing, coordinating, developing, marketing, testing, implementing and reflecting. The center of consciousness is composed of the collective egos in the organization arranged and empowered by the structures instituted by its leadership. This component of the organizational psyche is intricately connected to the organizational archetypes manifesting its activities in accordance with the archetypes that are active in organization and in their level of maturity.

The center of consciousness also has a predominately masculine or feminine character. This is driven not only by the gender of the constituency inside an organization but by the manifestation of the anima and animus archetypes. Certain organizations, like the army, would operate in an animus (masculine) set of characteristics because of the nature of their mission, regardless of how many females it has enlisted in its ranks. In contrast, most healthcare provider organizations and schools exhibit anima (female) characteristics given its care and nurturing missions. This is also irrespective of employee gender, although actual gender membership significantly influences the masculine vs. feminine attributes of an organization. Corlett & Person (2003) define three signs of masculine/feminine balance in an organization: a) balanced gender by relatively equal numbers, b) level of comfortableness by each gender inside the organization, and c) both females and males are part of the decision-making process.

The public face of the organizational psyche corresponds to Jung’s concept of the persona. The persona is how individuals present themselves to the world and is driven by two sources: “the expectations and demands of society and the social aims and aspirations of individuals” (Stein, 1998, p. 115). The organizational analog provides a filter through which energy flows in and out of the organizational psyche in its connection with the outside world. It is where the brand identity of the organization lives. It transmits the ideal images of itself to the outside world hiding aspects which are deemed “internal” by the organization’s leadership. In the end, the public face of an organization is a set of tradeoffs between what the organization is willing to share and what the world expects from it. Not conscious but still present in the organization’s public face will be artifacts that capture unconscious activity that is not congruent with the public image. For instance, an organization in healthcare may portray itself as caring for the wellbeing of all customers through its products and services yet may have an inadequate medical insurance program for its employees driven by their desire to save money. In this example, the artifact, the medical insurance program, is incongruent with the desired external image.

Organizational Unconscious

Corlett & Pearson (2003) begin the definition of the unconscious with the collective unconscious. They state that the collective unconscious serves as the foundation for the entire psyche of the organization as it does for its individual analog. It is the container for the neurology that defines us as human beings and “resides in the inherited structure of the brain” (Corlett & Pearson, 2003, p. 14). It contains two types of structures: instincts and archetypes. Instincts are the consistent modes of action common to all humans that do not require cognitive engagement. Instinctual actions just happen without ever being taught (Stein, 1998). Archetypes are psychic patterns that shape human behavior. They can be understood as the controlling patterns in the mind that regulate how we experience life. Archetypes represent our basic responses to organizational life. Quoting Morley Segal, Corlett and & Pearson (2003) state that archetypes are “key contributors to organizational culture, many of them representing the forms or outlines of the basic responses to organizational life” (p. 15). From these definitions, we can see that archetypes are the seed to the responses (mental capacities) to the problems in organizational life (the life conditions).

The organizational unconscious is the unique array of “energies, contents and truths” (Corlette & Pearson, 2003, p. 15) that operate beyond the conscious control of the organization. It is the bridge between the conscious organization and the collective unconscious. It provides the psychodynamic environment for these two forces to interplay. It is composed of the shadow, the participation mystique, the complexes and the organizational archetype.

The shadow comprises the collection of what has been repressed because the organization does not allow it by its rules, procedures or values. Commonly repressed elements of organizational life include feminine characteristics in an animus (male) dominated environment, feeling and intuitive preferences in a rationally dominated institution, and freedom of expression in a tightly controlled hierarchical institution. The shadow of an organization, like its individual counterpart, is its alter ego. It contains both positive and negative energies and subtly affects how the conscious organization goes about its business. The shadow contains features that are contrary to customs and group moral conventions. Stein (1998) states that the shadow contains features that are contrary to customs and moral conventions and that everyone has one. He also posits that the shadow is not experienced directly by the ego because it is part of the unconscious, and that instead, it is projected onto others. In the context of organizations, the shadow’s projections would go to outside entities, like the competition, or would be channeled as projections between internal functions.

The participation mystique is the part of the organizational unconscious that links individual egos to the organization. It provides the attractor that makes an individual want to be part of a given organization. It is the conduit for the organizational archetypes to be expressed by each person in the organization. The participation mystique is a term coined by Jung. Corlett & Pearson use it to describe how an organizational archetype connects to each individual. In this model of the organizational psyche, multiple archetypes would find expression through a single person.

Organizational complexes are containers of memories, thoughts and feelings experienced as work progresses through the activation of a given archetype. They are in essence the underlying assumptions that form at the unconscious level in the act of doing business. Over time, these complexes uniquely identify an organization and provide the basis for its culture. Values and beliefs are built upon complexes and change over time as the environment (life conditions) provides opportunities to solve new problems (mind capacities). For instance, teamwork and collaboration has evolved to a much higher degree in the last 30 years. This aspect of work life is driven by the Lover archetype that regulates how people work and relate to one another. The degree of collaboration has a lot to do with this archetype. In the last three decades, the teamwork and collaboration complex has evolved across most organizations. With this evolution, the value of collaboration has changed. Teams have evolved from simple work containers to social structures with democratic, dynamic empowerment and demonstrable higher performance.

The organizational archetype roughly corresponds to the archetypal self in individuals. It serves as a significant source of energy for the organization and provides the pattern for how it operates. Individual aspects of the organizational archetype connect to the universal collective unconscious archetypes from which they draw their patterns. Corlett & Pearson (2003) define the organizational archetype as having four dimensions or Life Forces. Each life force contains elemental archetypal energies aligned with a particular aspect of work life.

The life forces are arranged in two pairs of complementary forces that seek balance with one another. The first pair is focused on people and results. The people life force is how an organization relates to its employees and how they relate to each other. The results part of the archetype encompasses how the organization gets things done. The second pair of the life forces is learning and stabilizing. Learning is how an organization gains knowledge, takes risks and moves through the creative process. In turn, stabilizing is concerned with how an organization manages itself in terms of what it provides to its employees and the processes and controls it has in place. In a healthy organization, both life force pairs should be balanced. Figure 2 shows the arrangement of the organizational archetype, the life forces and the individual human faces of the organizational archetypes in each life force.

Figure 2. The organizational archetype and its components. This mandala-like arrangement was adapted from a similar drawing in Corlett & Pearson (2003, p. 18)

Life Forces and the Twelve Human Faces of the Organizational Archetypes

Figure 2 depicts twelve human faces of the organizational archetype. These are individual archetypal energies that produce specific psychic patterns in the organizational unconscious leading to the formation of complexes that ultimately define the organization’s culture. The genesis of these archetypes is the work of Carol Pearson who has performed considerable research in Jungian depth psychology and has been able to synthesize a large collection of archetypal definitions into twelve faces. Her work is documented in a number of her books and articles. In her partnership with John Corlette, Ms. Pearson expanded her twelve archetypes into the faces of the one organizational archetype. These authors jointly introduced the concept of the life forces that was described in the previous section. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each human face of the organizational archetype.

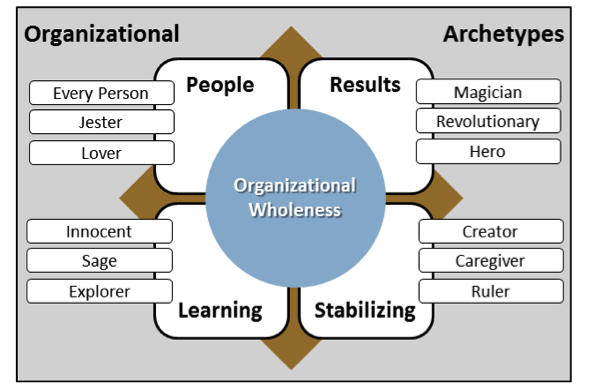

Table 1. The twelve faces of the organizational archetype. The definitions for this table come from Corlett & Pearson (2003), and Pearson (1991, 1997).

| Human Face | Positive Pattern | Negative Pattern |

| Every person (Orphan) | Pearson originally called this archetype the Orphan to denote its inherent dependency psychology. The every person version denotes the individual who is part of an organization needing considerable support. Organizations with this archetype have a strong belief in the importance of each individual and tend to single out those who distinguish themselves with their performance and accomplishments. | The Orphan has a strong sense of being abandoned. This translates into employees not trusting their leaders and in feeling that everyone is out to get them. Scapegoating is a characteristic of the Orphan. |

| Lover | This archetype is manifested in the level of respect between the company and its employees. It is also established in how people communicate. The Lover archetype is positively expressed through direct communication and emotional honesty. Consensus is a characteristic of the Lover as is passion and engagement. Collaboration and support are found in organizations with a strong Lover archetype. Closeness is another attribute of this archetype. | The negative side of the Lover translates into a large number of emotional dramas, over-emphasis on consensus, group-think, and cliquishness. |

| Jester | The Jester archetype brings enjoyment and fun to the work environment. It is manifested in “lightness” in the interaction within the company and its stakeholders. Jester organizations have a good work-life balance, enabling employees to work from home and have flexible time. Also, the Jester brings celebration to the workplace for milestones, personal events and holidays. | The negative Jester gives way to dark humor, con artistry, low ethics, and a total disregard for rules, procedures and standards. |

| Hero | This is the most common archetype in western organizations. It brings the energy of working hard to make the world a better place. The Hero translates into vitality, competition, discipline, focus and determination. There is a fair amount of self-sacrifice in the Hero for the betterment of the larger whole. Hero organizations usually have a cause and are able to enlist employees in working for it. These organizations value the actions of the Hero and recognize them with a number of rewards. | The negative Hero creates the need for an enemy. This type of Hero can be arrogant, impulsive, obsessive and ruthless. Negative Hero organizations tend to overwork their people and expect ongoing sacrifices. These organizations also tend to be lower in their financial compensation than most. |

| Revolutionary | This archetype provides the counter story to the typically linear direction of the organization. Revolutionaries are troubleshooters and tangential thinkers. They look for the reasons why the glass is half empty. They are change agents looking for continuous improvements. Revolutionary organizations are able to make tough calls such as dealing with non-performers. | Negative Revolutionary organizations can be dark places where fear is a regular characteristic. In these organizations people get fired for no apparent reason and employees are also afraid of what may happen to them. Also, the permeating attitude is one of “nothing is good enough.” Change for change sake is another of the negative characteristics of the Revolutionary archetype. |

| Magician | This is the transformative energy inside any enterprise. It is responsible for the “level 2” changes. Innovation, high energy, and flexibility are characteristics of the Magician. Organizations with a highly developed Magician archetype are extremely adaptive and respond easily to changing markets and world conditions. Magicians are systems thinkers and natural change agents | The negative Magician archetype is manifested in manipulative energy, lack of follow-through, and working on seemingly innovative tasks that have no purpose. Organizations with a negative Magician archetype start a lot more projects than they finish. |

| Innocent | An organization expressing the Innocent archetype is typically highly hierarchical with centralized power at the top. Management’s role is that of a guardian and the company is seen as the provider of the employees’ wellbeing. Employees trust management and seek guidance in their development. Learning is passive and directed by management. Innocent organizations lack innovation and tend to be involved in simplistic work. | The negative side of the Innocent archetype translates into victimization, denial, and resistance to change. The Innocent organization prefers maintaining the status quo. |

| Explorer (Seeker) | Pearson used “Seeker” as the original name of this archetype. It brings the sense of individuality, exploration, risk taking and self-discovery. This archetype is essential to the emancipation of the employees. Without it, growth inside the workplace would be limited. The Seeker takes responsibility for his/her own learning and channels new knowledge into worthwhile endeavors at work. Explorer organizations tend to be flat and democratic, allowing individuals to work at their own rhythm and time. | Negative Explorer organizations will conduct activities that are uncoordinated and with little accountability. Minimal to no planning is practiced by these organizations. Also, inadequate records are maintained. These organizations do not pay proper attention to their employees, their needs and problems. Given their loose management structure, there is potential for chaos. |

| Sage | The Sage archetype correlates to Senge’s (2006) learning organization. As learning grows from the Innocent to the Explorer and then the Sage, the organization is accumulating knowledge that is leveraged in practical ways through achieving and demonstrating mastery. Sage organizations establish centers of competency in true practice and not in name only. Systems thinking is a hallmark of Sage organizations. Ongoing reflection, action learning teams and transformative learning practices are also characteristics of Sage organizations. Learning is an integral part of daily work life. | The negative Sage organization can be emotionally detached appearing uncaring and inhumane. It may also be disconnected from the needs of the market and work on the wrong things. Over analysis is another strong potential of the negative Sage individual or organization. Ivory towers and intellectual elite can emerge in these organizations. This would limit those who can learn and who can express their ideas freely. |

| Caregiver | The Caregiver is the necessary archetype for an organization to provide for the wellbeing of its employees. This care ranges from basic benefits to personal development. The Caregiver is also manifested by the care of the organization for the community and the social system in which it operates. Harmony, cooperation, and support for each other are characteristics experienced by the employees in Caregiver organizations. | Negative Caregiver organizations tend to over work its people, experience burn out, have low mutual respect, and experience high turnover. Compensation is low and people are expected to work long hours. These organizations typically avoid confrontation being overly passive. Delegation is not actively practiced by management. |

| Creator | The Creator archetype expresses innovation and the creative processes in an organization. This archetype provides the counterbalance to the Explorer. It provides the vehicle for the Explorer’s knowledge to turn into something tangible. In the Creator, there are elements of imagination, artistry, and vision. The challenge for this archetype is its disdain for formality, bureaucracy (either real or perceived) and the potential of applying creative energy to non-necessary endeavors. | Negative Creator organizations do not adequately support employee creativity. They also have the attitude that nothing is good enough. A natural inattention and frustration with routine and rules exists. In addition, there is almost paranoia about “selling out” to the demands of the market. |

| Ruler | This archetype is about maintaining order and creating harmony out of chaos. It implies a sense of responsibility, balancing and allocation of resources. Either as individuals or organizations, it is manifested as decisions, authority, process, systems, goals, and strategies. The challenge for the Ruler is being fair and non-tyrannical. Decisiveness and direction need balance with methods and unique situations of others. | Negative Ruler organizations are hierarchical and bureaucratic. In addition, they tend to be less tolerant of diversity and appreciate people that do as they are told. Power is centered at the top of the organization and lower levels are viewed as lesser. Image is more important than actions. In extreme cases, negative Ruler organizations oppress, cut ethical corners, and are inflexible to change. |

The twelve faces of the organizational archetype defined above do not explicitly correlate to gender in form or psychic energy. They can all be manifested in masculine or feminine organizations and in male and female individuals. However, the psychic energy of these archetypes can be colored by the Jung’s anima (female) and animus (male) archetypes. The workplace has been evolving and becoming more gender neutral. However, there are some of the faces of the organizational archetype that would have more of a bias toward one gender than the other. The Caregiver archetype would have an anima/feminine inclination. As an example, there is a higher presence of females in Human Resource department where decisions are made on how employees will be cared for. In contrast, there is a higher male population in management and the Ruler archetype would have an animus/masculine bias.

This essay will continue to examine the twelve faces of the organizational archetype in their correspondence to the ECLET value system (to be introduced in the next section) and in its application as represented in the case study. For the rest of this essay these twelve faces will be referred to as organizational archetypes for simplicity.

The Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory (ECLET)

Gravesian Theory

Dr. Clare Graves developed the Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory (ECLET) from the data he collected from 1952 to 1959 regarding the personality of the mature adult in operation (Lee, 2009). Graves did not have a theory in mind when he started his research. He simply wanted to understand the differences in personalities of mature adults as they relate to their human experience. This inquiry started as a response to questions from his students as they pondered which theory of human psychology was correct (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). His research was simple in structure as it involved having his students write an essay describing the personality of a mature adult in operation. The data collected in the 1950’s included over a thousand essays from students raging 18-61 in age (Lee, 2009, 8).

Dr. Graves used a trained panel to classify the data as it was being collected over the seven-year span. The initial classification yielded two groups: one for individuals whose concept of the mature adult was denying/sacrificing self and the other about expressing self (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Upon further analysis, the sacrifice-self group was determined to have an external locus of control and aimed to make meaning of life through input from the world, resulting in actions to modify or improve self. In contrast, the express-self group was found to have an internal locus of control, that is, getting direction exclusively from within and focusing actions on changing the world.

As Graves’ research continued, the panel involved in the classification further separated each group into two subgroups yielding four classifications. They determined that the sacrifice-self individuals could a) “deny/sacrifice self for reward later” or b) “deny/sacrifice self now for getting acceptance now” (Lee, 2009, 19). The subgroups associated with the express-self subjects could a) “express self in calculating fashion and at the expense of others,” or b) “express-self as self desires but not at the expense of others” (Lee, 2009, 20). A fifth group emerged later as Graves continued his research belonging to the express-self category. This newly found group also shared an internal locus of control but it focused on expressing self impulsively at any cost. This last group was found in the early 1960s (Lee, 2009, 28).

Through his continued research, Graves realized that the classification of his subjects did not remain static. He followed up with the lives of many of the individuals who participated in the research while at the same time adding more data points (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Graves determined that individuals changed their idea about what a mature adult should be like. That is when he conceptualized an evolutionary cycle that alternated between expressing self and denying/sacrificing self. He documented this evolutionary pattern as follows:

- Expressing self impulsively at any cost—changing to

- Denying/sacrificing self for reward later—changing to

- Expressing self in calculating fashion and at the expense of others—changing to

- Denying/sacrificing self now for getting acceptance now—changing to

- Expressing self as self desires but not at the expense of others

There was a sixth classification that was noted in the transitions as individuals evolved. This group was another deny/sacrifice self that evolved from the last express-self group that focused entirely on existential realities. It is at this point and throughout the 1960’s that Graves developed and matured ECLET. His conclusion was that his classifications represented the amalgamation of unique life conditions and mind capacities that form part of human evolution. The life conditions present the collection of problems that individuals need to solve, while the mind conditions correspond to the problem-solving neurology currently active in each individual. The recorded evolution from one group to the next had to do not only with a change in life conditions (new problems) but a neurological transformation that readied the individual to operate at the new level.

As Graves prepared his first set of essays on ECLET, he added two entry level classifications which preceded the one on express self impulsively. In ECLET Graves theorized that humans evolved from primitive man to contemporary beings not just physically but socially and psychologically through what he ended up with: eight levels of human existence combining life conditions with mind capacities. His first level places early humans in clans dealing with the problems of survival of food and shelter. His eight-value system, albeit embryonic, has humans focused on existential problems since subsistence problems would be fully solved for people at this level. In his theories, Graves posits that the first six levels of human evolution are fixated on issues of subsistence ranging from physiological survival to mastery of materialism. The last two systems, he viewed, function at a higher octave repeating the basic patterns of the first six but operating at a level of beingness no longer preoccupied with subsistence but rather focused on the higher purposes of being human.

Graves utilized a simple notation to refer to the eight value systems in ECLET. He used the letters A – H to represent the life conditions and N – U to denote mind capacities. The pairing of the two letter sequences identifies each of the eight value systems. These are: A-N, B-O, C-P, D-Q, E-R, F-S, G-T and H-U. Using D-Q as an example, this is the sacrifice self for reward later level which has “D” life conditions or problems and “Q” mind capacities to solve them.

Graves conceived that humans evolve from A-N to H-U and beyond. However, he also found in his research that given harsh life condition changes, humans could regress to a lower level. Additionally, humans could enter or exist in an environment that is different from their mind capacities. For instance, humans with “R” mind capacities could be in a system with “D” life conditions. ECLET conceives mind conditions to be nested or accumulative. A person with “R” mind capacities has the neurology to understand and operate in any system raging from A through E. Graves theorized that most humans operate in a combination of a sacrifice and express-self mind conditions. His research showed that a small number of people operate in a single mind condition system. He termed this rare mature adult in operation “nodal.”

According to ECLET, human beings transition from one system to the next when a number of conditions are met which result in a “higher level of neurological direction of behavior” (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Graves identified six conditions necessary for the transition. The first is the potential in the brain. Unless impaired, the potential for all system exists in the human brain. Second, the individual should have resolved the existential problems in the current system. According to Graves, this resolution releases the psychic energy needed for advancement. Thirdly, a dissonance associated with the breakdown in the solutions at the current level must occur. Graves found that all individuals making a system transition do so after a period of crisis and actual regression. The experienced dissonance results in the biochemical transmutation necessary to alter the neurology needed to solve problems at the next level. It is at this stage of regression where the individual prepares to move forward but could also arrest development or actually regress to a previous level. The fourth condition and the one responsible for stopping the regressive process is insight. This condition involves having insight into the new ways of solving problems. The next condition, the fifth, is overcoming barriers. Relationships and other constraints from the previous system must be overcome. Most relationships ground humans in one system and provide resistance for an individual to move on (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Consolidation is the sixth and final condition. It involves the practice and affirmation of the new way of solving problems.

Don Beck and Chris Cowan, the authors of Spiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadership, and change (1996) worked with Dr. Graves for a period of 10 years prior to his death in 1986. Both of these social scientists saw the applications of ECLET as a lens to understand and work with organizations. Their book positioned ECLET as a management set of principles and tools. To make Graves’ levels of evolution more accessible to the general public, Cowan devised a color scheme to replace the A-H and N-U letter nomenclature. The colors denote only the “nodal” state of a system and not its life condition/mind capacity pairing. Table 2 provides the key attributes of the eight value system in ECLET.

Table 2. The eight value systems in ECLET. This table adds the color correspondence introduced by Cowan in spiral dynamics. The contents of this table are based on the article “Human nature prepares for a momentous leap” published by The Futurist in 1974 (p. 72-87) and reprinted on Cowan &Todorovic (2008).

|

Value System |

Spiral Dynamics | Thinking | Motivation | Means/End Values | Problem of Existence |

|

A-N |

|

Automatic | Physiological | Purely reactive | Maintaining physical stability |

|

B-O |

Purple | Autistic | Assurance | Traditionalism/safety | Achievement of relative safety |

|

C-P |

Red | Egocentric | Independence | Exploitation/power | Living with self-awareness |

|

D-Q |

Blue | Absolutistic | Peace of mind | Sacrifice/salvation | Achieving ever-lasting peace of mind |

|

E-R |

Orange | Multiplistic | Competency | Scientific/materialism | Conquering the physical universe |

|

F-S |

Green | Relativistic | Affiliation | Sociocentry/community | Living with all humans |

|

G-T |

Yellow | Systemic | Existence | Accepting/existence | Instilling sustainability in the planet |

|

H-U |

Turquoise | Differential | Experience | Experiencing/communion | Accepting existential dichotomies |

Today, spiral dynamics is highly regarded by organizational development professionals and managers in all types of industries. Dr. Beck has applied the principles of ECLET to a large number of organizations ranging from the Dallas Cowboys to the country of South Africa. Chris Cowan made his life mission to preserve the theories of Dr. Graves through his books, articles and seminars. Although much of the original research has been lost by practitioners (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008), the principles of ECLET as reflected in spiral dynamics are in use today to aid in the problem solving at every level of the human evolution.

The Eight Value Systems

This section describes the core attributes of each of the eight ECLET value systems. Table 3 provides a summary of the life conditions and mind capacities associated with each. Through this table the evolution of human life conditions can be appreciated along with each human response to deal with their related complexities. Mind conditions need to solve the problems at each level of the ECLET framework in order to fully evolve (Beck & Cowan, 1996).

Table 3. Life conditions and mind capacities for the ECELT value systems. The contents of this table are adapted from Cowan & Todorovic (2008) and A mini-course in spiral dynamics (2001).

| Value System | Life Conditions | Mind Capacities |

| Beige (A-N) |

|

|

| Purple (B-O) |

|

|

| Red (C-P) |

|

|

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

| Yellow (G-T) |

|

|

| Turquoise (H-U) |

|

|

Beige (A-N)

This is the most fundamental and original system of human existence which dates to the early stages of human evolution (100,000 ago). Beige no longer exists in pure form (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Even the most basic of clans or tribes have been affected by external civilizations and have evolved to the next levels of existence. A-N is an express-self system although the concept of self is not fully developed. People in the beige system did not have a fully awaken self-identity. Their main focus was survival, motivated by hunger, sleep and other physical needs. These beings did not possess a sense of time, distance, or causality (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Modern humans can temporarily regress to the beige system during intensely traumatic situations.

Purple (B-O)

The next step in evolution is the purple (B-O) existence level which took place around 50,000 years ago (Beck & Cowan, 1996). This is a sacrifice self-value system. The sacrifice is for the way of the collective as established by its elders. The identity of the individual is purely based on belonging to the tribe. Myths, traditions and customs create meaning for purple. All unexplained phenomena are regarded as part of the spiritual realm. Wisdom and direction come from the elders of the tribe. Members seek protection from this collective. Causality is not yet discovered and sense of time is based on the seasons and their natural markers. This value system introduces dichotomy into the human psyche. With this, the sense of right and wrong arises along with what is taboo and superstition. Purple individuals are animistic assuming the presence of a life force in everything. At the core of all family life the essence the B-O system is still active. “Family oriented” organizations also exhibit B-O characteristics and in some cases expect a purple-type relationship, including the dependence on each other and the leadership. Sports teams, military platoons, survival groups and close-knit families represent this type of ECLET existence level outside actual tribes.

Red (C-P)

This value system is the first to express complete self-identity. The group identity of purple is shed in favor of an egocentric conceptualization. Instant gratification and personal power are the centerpieces of the Red (C-P) system. It first appeared on the planet about 10,000 years ago. C-P individuals have a spontaneous and impulsive expression. They have a sense of being threatened by the environment and others. Consequently, they seek domination as a way to cope with this threat. People in the red system do not feel any guilt in their actions but they experience shame (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). They can be proud, lustful and violent. Might is right and their world is one of the “haves” and “have-nots.” This system is widely present in our planet today even in forms of government where an individual controls power using force to maintain it. It is also a system that all humans go through growing up during the years of teenage independence. As humans mature, the effects of red system are reduced or shut down for the most part. Gangs, sports teams, people at war, and anyone in physical danger can experience the C-P value system in full force.

Blue (D-Q)

This is a sacrifice system for the benefit of some reward in the future. Blue is absolutistic with the conception that there is only one truth. The values in blue result in an ethnocentric worldview. There is a strong sense that those that are different are not living correctly. All of the organized forms of governments and religions are blue systems (Beck & Cowan, 1996). They provide order, operate in a hierarchy and expect members to comply. The blue system started about 5,000 years ago (Beck & Cowan, 1996). The view of the world in D-Q system is that it is “orderly, predictable and unchanging” (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). There is a sense that what takes place is predestined by some higher power that more often than not is conceived as God. Security in the blue system comes from accepting this faith and direction. Guilt is a primary feeling in D-Q which comes from evolving out of the guiltless red system. Blue is also referred as the “saintly” value system (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005).

Orange (E-R)

The orange system is multiplistic and as such operates under the assumption that there are always options. This is the system that returned Apollo 13 back to Earth safely. Orange dares to ask questions not as defiance but as a way to find the best possible path of many (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). There is no single truth in orange, just a more correct path. This system is about having the freedom to choose. It favors change and improvement. People in the E-R system do not seek to be right just to be “best in class” at what they do (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Competition, winning and risk taking are some of the key attributes of orange. The driving force for this system is to control one’s world for personal ends. Orange is the world of science, rational thinking, and efficiencies. Its aim is to master the material world. Success in this system may include manipulation, which is justified as a mechanism for achieving results. In orange, all things are tied to an economic value. Consequently, this system can easily generate ambition, greed and lust. Orange individuals prefer autonomy and independence, and as portrayed in today’s media, pursue abundance and a good life. Most of the innovation of the world has come up from the E-R system that started 1,000 years ago but intensified with the industrial revolution (beck & Cowan, 1996).

Green (F-S)

Like blue, F-S is a sacrifice-self system. However, in this case the sacrifice is for the benefit of being accepted now. Green is a relativistic system with no absolute truth. All humans have their place and diversity is revered. Emotions in green are respected and form the basis for true affection. Empathy is how others are accepted in contrast to red’s pity, blue’s compassion, and orange’s consideration (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). Empathy in this system is of greater value than logic. People in the green value system can tolerate doubt and ambiguity, and can exhibit a larger sense of curiosity than the others. Social and environmental sustainability are the hallmarks of green. From this notion, green individuals see each other as equals and pursue social and economic justice. Community and unity are pursued in green. Relationships and being liked is more important than compensation and power for these individuals. There is a strong need to be accepted and to do what the group needs and wants. The F-S system has been available for about 150 years (Beck & Cowan, 1996).

Yellow (G-T)

Yellow is a system of self-expression. It is the first system operating in the second tier of existence according to Dr. Graves (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). Like green, it is relativistic and contextual. Its core relational value is empathy. The yellow system adds the systemic mind capacity to green. Thus, system thinking is a core capability of G-T. Yellow individuals unlike their counterparts in all other systems are not impulsive and have left behind the fear of existence. Both of these attributes make them operate in a truly collaborative manner. They have the certainty that their needs will be met in some form and do not feel the need to compete (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008).

Even though yellow is a self-expression system, it has a considerable amount of affect. The people in this system are warm and approachable. Their self-interest pursuits are bound to not cause any harm to anyone. Yellow individuals require flexibility and operate best in open systems. They profess a deep humility and a reverence for all of life. People in the G-T system do not have fixed values. These emerge from current understanding of their condition. Motivation in yellow is self-generated and learning is mostly through observation and participation is a variety of situations. Leadership in the G-T system applies a similar leadership style to beige where the best fisherman should be the one fishing but at a higher octave. In the yellow system, the leader is the best person to guide others while the conditions and the individual’s situation are aligned. This system first appeared about 60 years ago (Beck & Cowan, 1996).

Turquoise (H-U)

Not much is known about the turquoise value system. In his entire research, Dr. Graves only found 6 individuals that exhibited a different conceptualization of the mature adult in operation than the previous seven systems (Lee, 2009). His turquoise (H-U) system definition evolved from this limited sample. In this value system our current problems of existence are solved and give way to another set of challenges on how humans continue to evolve. There is no timeline on when H-U could be present and its impact felt on our planet. Its availability is predicated on the problems that yellow would create (the new life conditions) to give way to the emergence of the turquoise mind capacities needed to solve these problems. Graves and the students of spiral dynamics speculate that the yellow system would solve the basic problems of existence, a preoccupation with all the other systems prior to yellow. Given life conditions where basic living is no longer an issue, what would the mind capacities need to be? In a simplified way, this would be equivalent to retirement with all needs met, including physical, mental and emotional. In our current conception of life, retired individuals with monetary security do not necessarily have the confidence that their other living needs will be met such as emotional support. H-U makes that possible.

The Modernistic and Post Modernistic Organizational Value Systems

The value systems of organizations are the amalgamation of the value systems of the people in the organization (Beck & Cowan, 1996). Schein (2010) states that culture is set by the leader or the leadership of the organization. In the same vein, organizational value systems are established by their leadership with reinforcing contribution by all members.

Contemporary organizations are mostly D-Q and E-R with some F-S in the mix (Lee, 2009). Traditional and hierarchical organizations would tend to mostly exist in the D-Q system while highly entrepreneurial and democratic organizations like Google would gravitate toward the E-R system. As it will become evident later in this essay by the attributes of F-S, there are not many pure organizations in this system (van Marrewijk, 2004). Organizations like Ikea and Interface Flor operate in an E-R world but bring a lot of F-S through their social and environmental sustainability programs. Their leaders demonstrate solid F-S characteristics and drive the culture of their companies with aspects of this value system. However, they are not pure F-S organizations.

G-T (yellow) organizations do not yet exist in any documented form (van Marrewijk, 2004). However, Lee (2009) forecasted a sizable percentage of individuals having G-T characteristics now forming part of modern organizations. In an interview with Dr. Beck he posits that yellow and turquoise value systems will come together a later time when problems created by the F-S system are fully apparent and require the full thrust of the yellow mind capacities (Roemischer, 2002).

The descriptions in Table 4 correspond to the value systems most applicable to today’s business organizations. Systems that precede D-Q are present in these organizations but are not the dominant value system. For instance, Red (C-P) exists in all organizations but in its pure form would exist in more power-based organizations such as gangs and organized crime.

Table 4. Attributes of the D-Q, E-R and F-S value systems along archetypal life forces. This table uses the Corlett & Pearson (2003) life forces to organize the key attributes of organizations in the blue, orange and green systems. Material for this table comprises of summaries and abstractions from text in Cowan & Todorovic (2005) and Beck & Cowan (1996).

| Life Force | Blue (D-Q) | Orange (E-R) | Green (F-S) |

| People (Organization Structure) |

|

|

|

| Results |

|

|

|

| Learning |

|

|

|

| Stabilizing (Managing) |

|

|

|

Analysis of the Organizational Archetypes in Each Value System

This section establishes a correlation of the ECLET value systems with the twelve organizational archetypes. Only the modernistic and post-modernistic value systems are considered (D-Q, E-R and F-S). Each correlation appears in the form of a table showing the behaviors for employees and then the organization as a whole for each individual archetype in the three values systems considered in this study. The correlations in this section come from the author’s own findings on the work of Dr. Graves on ECLET and Dr. Pearson’s organizational archetypes. A part of this research comes from the Spiral Dynamics course offered by Chris Cowan and NatashaTodorovic taken by the author in May of 2011.

Innocent

In general, the Innocent archetype influences individuals and organizations that are benevolent and operate in a highly hierarchical and centralized structure. An Innocent organization acts as the caring parent and the employees as the well-behaved children. This archetype is more prevalent in the blue value system (D-Q) than orange (E-R) or green (F-S). D-Q lends itself to the organizational parent/child relationship, given that this coping system is based on denying self for a reward later and to obey proper authority (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). This system also seeks to create comfortable spaces and rightful living. The other value systems tend to have more dynamic environments and thus may challenge the Innocent archetype. Table 5 relates the characteristics of the Innocent archetype to each of the value systems being analyzed in this essay.

Table 5. Correlation of the Innocent archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Everyday Person (Orphan)

Like the Innocent, the Orphan archetype drives individuals to seek safe organizations that can provide for them. Unlike the Innocent, the Orphan does not believe that the world is safe. Consequently, orphans feel betrayal at every corner, self-sabotage, and ultimately feel powerless. Orphan organizations are those that have experienced what is perceived as some form of betrayal or abandonment. Examples include takeovers, changing market conditions and poor leadership (Pearson, 1997). Unlike the Innocent archetype, the Orphan can easily live in the three value systems being analyzed. The structure and characteristics of D-Q can simply provide the life conditions for both Orphan organizations and individuals to exist. E-R is also a good candidate because of its competitive nature. In the E-R world there are winners and losers. The losers could feel that the larger E-R system did them wrong and feel victimized. F-S is also capable of experiencing the Orphan. Fighting for a cause for social and environmental integrity could be rejected by the public, authorities and businesses. Lack of vertical system integration (seeing how other value systems see the world) could make an F-S organization or a set of individuals embody the Orphan archetype. Table 6 shows the characteristics of the Orphan archetype in its relationship to the Spiral Dynamics systems.

Table 6. Correlation of the Everyday Person archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Hero

The Hero archetype is well entrenched in the workplace culture. Modern organizations have reward and recognition systems that perpetuate the state of employees sacrificing themselves for their benefit. This self-sacrifice is supported by general business culture, the media and our upbringing. Heroes are disciplined and fight for a just cause (D-Q). They are competitive and strive for victory (E-R). Their plight is for the benefit of the whole. The ideal Hero is selfless and aims to build a better world (F-S). Table 7 shows the characteristics of the Hero archetype across the value systems.

Table 7. Correlation of the Hero archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Caregiver

This archetype brings the characteristics of selflessness and sacrifice for the benefit of others. On the surface it is most aligned with the F-S value system. However, it can be found in Blue (D-Q) and Orange (E-R) as well. The motivation of selflessness is different in each system. In D-Q, the motivator for the Caregiver is to provide for the needs of others in the social system because that is what a benevolent person or organization does. The sacrifice for D-Q is aimed at the longer term. The concept of “reap what you sow” is at play for the D-Q Caregiver. For E-R, the motivation is to empower and to provide what others need to compete and win. The E-R Caregiver understands that without some level of care and encouragement an organization would fail. Caregivers act from their own sense of competitiveness but could be quite generous as long as those receiving benefits are contributing commensurably. In the F-S system, the Caregiver embraces the concept of service. These individuals and organizations provide for the needs of others purely because of their sense of community. Their understanding is that all should have what they need. The F-S Caregiver views that giving is its own reward. All caregivers in the three value systems are subject to being manipulated and “guilted” into giving. Table 8 shows the correspondence between the characteristics of employees and organizations expressing the Caregiver archetype and the value systems.

Table 8. Correlation of the Caregiver archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Explorer

The Explorer archetypes corresponds to what Pearson calls the journey in the development of an individual or organization (Person, 1997). The Explorer’s quest is about identity and purpose. It is through this archetype that individuals connect with their sense of vocation and organizations translate high level vision statements into a sense of purpose in the social systems in which they operate. The Explorer is a journey of discovery primarily involving learning, taking risks, and testing what works. The Explorer is what takes the Innocent to the next level in the Learning life force. The Innocent is content with being directed by the organization while the Explorer needs to find his/her own path. Explorer organizations are not content with just being in business. They must find its purpose and justify who they are to their social system. Apple, Inc. explored its entry into the entertainment market with several products to ultimately come up with the iTunes/iPod/iPhone combination that established a strong purpose for this organization.

The Explorer archetype is stronger in the E-R and F-S systems. Both of these systems leave authority behind and want to explore multiple alternatives. E-R is the multiplistic system and a natural to explore many paths to discover the “right one.” E-R learns by experimentation. Similarly F-S conceptualizes many paths buts its relativistic nature establishes that all paths are relevant. F-S learns vicariously by observation (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). It observes what works and what does not and it embraces the path that the group prefers without judgment. The Explorer archetype has difficulties in the D-Q system. Learning in D-Q is driven by consequences and even punishment. There has to be a consequence in place for D-Q to learn (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). For example, all employees need to have 40 hours of annual training or they will lose points in their annual review and get a lesser raise. The D-Q type of self-development borders with how the Innocent archetype learns. Table 9 establishes the correlation between the Explorer archetype and the value systems.

Table 9. Correlation of the Explorer archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Lover

The Lover archetype is about how organizations relate to their employees and how employees relate to one another. This is the next level of the People Life Force in the Corlett & Pearson (2003) archetypal model following the Orphan. The Orphan archetype needs to belong to an organization but has this natural sense of abandonment and betrayal. The Lover represents a mature level of relatedness that goes beyond “I-It” in Buber’s (1970) relatedness conceptualization. Instead, it embraces an “I-You” type relationship. Additionally, the Lover archetype provide a level of passion and commitment that brings energy to the organization awakening what Peppers & Briskin (2000) call ‘soul.” It is through this soul that employees find meaning in their work lives and where they honor their relationships. The Lover along with the Explorer archetype provides the emancipatory energies for individuals to find at least part of their personal realization though their work.

The Lover archetype is a natural in the F-S system that is socio-centric (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Relationships are at the center of F-S and given its life conditions and mental capacities, the Lover archetype should be highly developed in this system. The E-R system presents a challenge for the Lover archetype. E-R is an individualistic system where relationships are the means to an end. Teams and other structures in E-R are needed by individuals and organizations to compete, deliver products and services, and meet financial objectives. However, E-R organizations can have a high degree of passion and employee commitment. These attributes also come from the Lover archetype. In the D-Q system, which like F-S has an external (social) locus of control (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008), relationships are an important part of the system. D-Q would have more of the “I-It” type of relationships than “I-You” but respect could lay a fundamental layer of relatedness that makes the organization operate cohesively. In D-Q and E-R, norms of conduct and what are acceptable behaviors between employees is necessary to provide guidance and establish punishments (D-Q) and feedback loops (E-R). Table 10 shows the correlation between the lower archetype and the value systems.

Table 10. Correlation of the Lover archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Revolutionary

The Revolutionary archetype follows the Hero in the Results Life Force. The Hero in an organization is in tune with its needs and sacrifices self to address them. In contrast, the Revolutionary provides the counter story. It brings awareness on what needs to change and applies energy to its discovery and ultimate implementation. In its truest essence, the Revolutionary archetype correlates to change agents. Organizations that embody the Revolutionary archetype are not afraid of making hard calls and have an aggressive stance on non-performing personnel. Also, they are able to deal with non-performing products and services. A negatively inclined Revolutionary organization is a dark place to work where people are afraid of being terminated at a moment’s notice.

Both the D-Q and the E-R systems lend themselves well to house the Revolutionary archetype. A structured D-Q organization can use this archetype to clean house and remain vigilant on what is and what is not working. E-R organizations need the Revolutionary archetype to question their products and services, and their internal processes. The E-R organization actively seeks revolutionaries and encourages them to speak up. The challenge for this archetype is the F-S system. In a system that seeks harmony between its constituents individual revolutionaries would not have a place. However, F-S organizations would have complete groups acting as revolutionaries for internal change or for change in society. In this larger context, F-S organizations are the ones pointing out what is wrong in the world and how to fix it. Table 11 shows the correlation of the Revolutionary archetype with the ECLET value systems.

Table 11. Correlation of the Revolutionary archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Creator

The Creator archetype resides at the second level of the Stabilizing Life Force. This archetype brings the creative force into action manifesting it into new products and services, and internal improvements. The output of this archetype ranges from creations without much value for the most brilliant and purposeful. The Creator archetype works in tandem with the Explorer. It is the manifested counterpoint to the Explorer’s learning and developmental impetus. Organizations with a significantly active Creator archetype would produce the most innovative and life-changing products and services. Apple and Google are two examples of organizations that have changed the social landscape of information with their creativity.

The Creator archetype lives equally well across the D-Q, E-R and F-S systems. The motivation in each system is what differs. The Creator archetype in D-Q is focused on expanding and improving the products, services and internal systems already in place. There is strong sense of ownership present in the D-Q Creator archetype. The challenge for most D-Q organizations is the creativity applied to sales and marketing. Often these organizations do not achieve maximum potential because they fall short on the creative side of these functions. In contrast, E-R organizations understand sales and marketing and can support their creative archetype better. This archetype is the centerpiece of modern organizations in the E-R system. Most E-R organizations see their “secret sauce,” their creative secret formula as how they win in the marketplace. In the F-S system, organizations and individuals see the process of creation as the reward. Their motivation is to create solutions for others whether their business structure is commercial or non-profit. F-S creativity is viewed as a service for society and not just the organization. Table 12 correlates the Creator archetype and its characteristics to the D-Q, E-R and F-S systems.

Table 12. Correlation of the Creator archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Sage

The Sage archetype is the third level of the Learning Life Force. It represents the realization of learning after the journey of the Explorer archetype has been completed. In the organizational context, the Sage archetype translates into global perspectives, objectivity, deep analysis, rationality, planning, and detachment to outcome. The challenge of the Sage archetype is connecting its “wisdom” to the people in the organization. The Sage believes in humanity but may not be in touch with it. Academic organizations are expected to embody the Sage archetype along with any organizations deeply dedicated to learning, particularly deeper subject matters.

The Sage archetype has a home in all three values systems, D-Q, E-R and F-S. The level of humanity will vary, with F-S being the system with the most “heart” from the Sage archetype. The D-Q system Sage would be extremely rational and focused on the knowledge that would make the entire enterprise work well. This would be a highly mechanistic view of applied wisdom. In E-R, wisdom would be highly evolutionary constantly seeking the most advantageous approaches to make the organization perform. D-Q would distinguish their sages by title and position. In E-R, the title would be less important. However, Sages would be well identified and have exclusive power. The F-S value system would relate differently with respect to the Sage archetype. F-S would expect Sages to be integrated into the group and not have any special power. However, they would be highly respected and valued. The Sage archetype in F-S would inherently be humanistic, not just in concept but application. Table 13 shows the correlation of the Sage archetype with the value systems.

Table 13. Correlation of the Sage archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Jester

The Jester archetype corresponds to the third level of the Relatedness Life Force. Even though it symbolizes lightness and lack of structure, its directive is to seek wholeness by breaking through all restrictions and by dealing with matters that might have been previously ignored or blocked (Pearson, 1997). The Jester is linked with flexibility and being free to connect with a number of options. In an organization, the energy of the Jester brings lightness and fun to the work environment. Organizations like Southwest Airlines bring a sense of fun and joy to their daily activities, not just for the employees but those who come in contact with them. Jester organizations find imaginative ways to solve problems. They are unconventional and creative. Employees embodying the Jester archetype bring a sense of joviality to their activities. The challenge with the Jester is staying centered and focused. There is the possibility of getting carried away by the fun and not accomplish much or not knowing when to tune into a more serious demeanor.

It would be counter for an organization in the D-Q system to have the fully developed Jester characteristics since organizations in this value system seek order and structure and would frown upon individuals stepping out of this norm. E-R is a far more logical system to release the Jester archetype. The competiveness of E-R could be accompanied with the fun and lightness of the Jester. The period of the Internet bubble saw many E-R organizations providing many forms of entertainment and fun environments for their employees. The level of creativity achieved during that time was quite significant. The Internet companies attracted all kinds of individuals, even those that never saw themselves work in high tech organizations. The Jester and the high E-R energy was a powerful combination. With respect to F-S organizations, it is expected that they would be highly receptive of the Jester archetype. Community, love and appreciation are the cornerstones of F-S. Fun and enjoyment could easily complement these attributes. In fact, it would be counterintuitive to find an F-S organization devoid of the Jester archetype. They go hand in hand. Table 14 holds the characteristics of the Jester archetype in the context of the organizational value systems being analyzed in this essay.

Table 14. Correlation of the Jester archetype to the organizational value systems.

| Value System | Employees | Organization |

| Blue (D-Q) |

|

|

| Orange (E-R) |

|

|

| Green (F-S) |

|

|

Magician

The Magician archetype comes after the Hero and Revolutionary archetypes in the Results Life Force. Its focus is change, in particular, second order change. The Magician is the quintessential change agent. It brings the transformative learning and change to an organization. Large changes would be impossible without the Magician archetype. Organizations that struggle with change by experiencing large costs, delays and failures in their change initiatives have immature Magician archetypes. This archetype provides a multiplicity of options, can easily name the problem, define it and manage its complexity. Individuals expressing the Magician archetype are effective communicators, respectful of others and quite capable of conflict resolution. The downside of the Magician is translated into changes that are not necessary, working employees to exhaustion, manipulation, insisting to be cutting edge, and intolerant of non-intellectuals.