Commentary on a Presentation on Spiritual Intelligence and Integral Theory given by Cindy Wigglesworth to the London Integral Salon and EnlightenNext, Wednesday 25th May

Nicholas Shannon

Does it make sense to talk of “Spiritual Intelligence (SQ)”? And if it does, is SQ something that can be measured, and taught? Can we say that SQ is something that humans develop, and if so, could it be that it develops in humans in a series of stages? As someone who considers himself spiritually underdeveloped—I engage in no religious practices, believe in no Gods, and live pretty much a materialistic existence (even a 30 minute meditation is a bit of a stretch for me)—I went to Cindy Wigglesworth’s presentation on Spiritual Intelligence intrigued to learn more, but with something of a skeptical mindset. Would SQ turn out to be yet another conceptual fad to be fed to the public and corporate world in their thirst for the next “big thing”?

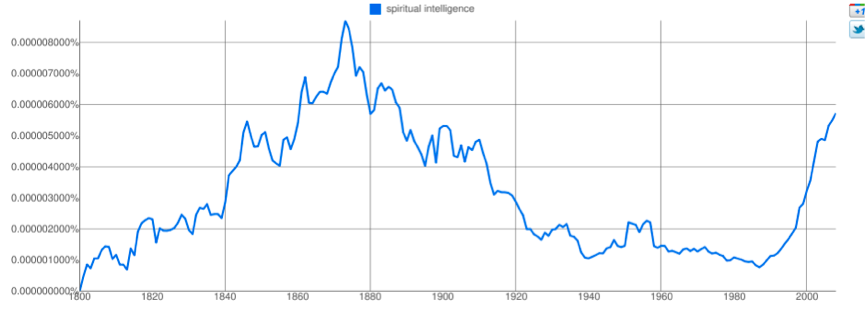

Popular Interest in Spiritual Intelligence

The concept of Spiritual Intelligence is never going to be an easy one to nail down. As much as philosophers and religious authorities have wrestled over the notion of all things “Spiritual”, scientists have bickered about the definition and measurement of “Intelligence”. One might say with some certainty, therefore, that uniting the two concepts into a single entity that is both measurable and teachable is an effort that is rife with controversy and disagreement. By consequence perhaps, not many have attempted such a task from outside the framework of a religious belief system. And yet, the concept appears to be soaring back into popularity in business and self-help literature. The chart below is a Google “ngram” showing the use of the term in English literature over the last two hundred years. If the chart is anything to go by, the current boom looks as though it still has a long way to run, the previous peak being somewhere around 1870!

It is possible that the current rise of interest in spiritual matters is being fueled by a certain existential “angst” created by a changing world order, difficulties with the consumer based economic system that has predominated over the last century, and growing concern about the vulnerability of the global ecosystem to the impact of human population expansion. “Sustainability” is a firmly established concept on the agenda of global corporations and social institutions, and is often promoted on the basis of ethics as well as business benefit. As organizations grapple with such moral issues they are inexorably drawn towards a consideration of other philosophical topics such as mankind’s search for meaning and purpose. To the extent that one of the tasks of leadership is seen as meeting the many needs of their employees, perhaps leaders in organizations are becoming curious about what it might be to foster greater “self-actualization” in their staff. Diverse organizations tread warily into such territory, aware that many employees will have their own religious beliefs and practices, hence there is a need to separate the notion of SQ from religiosity. Here then, is the territory into which Wigglesworth has journeyed—how to help organizations define and support the “Spiritual Intelligence” of their people on the basis that to do so makes sound business and ethical sense.

Difficulties with the Concept

Why might one be skeptical? The philosophical difficulty with the concept of the “Spiritual” unfolds in two related philosophical discourses: Ontology, which grapples with the question of existence—i.e., what it is to say something exists—and Epistemology, which grapples with the question of knowledge—i.e., what it is to know something. Since the “Spiritual” is by definition non-material and therefore not open to physical investigation via our senses, claims about its nature might be considered to be unjustifiable or purely a matter of speculation. On that basis, no one can legitimately claim any expertise in matters spiritual because such matters cannot be “known”. This philosophical difficulty is perhaps diluted, but not removed, if one accepts the view (first put forward by the philosopher David Hume) that even empirical investigation relies on certain assumptions about the nature of experience and the constancy of physical laws drawn from observation. Thus all knowledge claims are to be treated skeptically, not just those relating to spiritual matters.

Fast forward through nearly 300 years of philosophical debate, it could be said that the postmodern conception of knowledge holds that all knowledge is constructed by the mind and is therefore relative to the “knower” and the social context in which the knower is located. It therefore makes less sense to speak of knowledge and more sense to speak of ways of knowing. In Wilber’s (2000) terminology, the various domains of knowledge are all “true but partial” such that claims regarding spiritual knowledge (for example) can still be satisfactorily validated and falsified using 1st and 2nd person criteria for truth, such as the authenticity of the speaker or the mutual understanding of a group of people, even though they fail to meet 3rd person truth criteria—such as applied by scientists. A criticism of this view (suggested by Jeff Meyerhoff, 2010) is that it, too, may be “true but partial” and therefore of limited generalisability. That being the case, competing claims about the nature of Spirituality cannot be reconciled. They become a matter of belief.

If we are, then, still very much in the dark regarding the concept of Spirituality, we are also far from agreement on the nature of Intelligence. Here the debate has opened up, thanks to the work of Gardner (1993, 1999), Sternberg (1985) and Goleman (1996). Previously considered as a single entity or factor, the observation that many people are capable and successful despite an apparent lack of intelligence, highlighted the weakness of historical means of measuring the concept. For example, IQ tests such as Raven’s matrices (Raven et al, 2003) have been found to have racial and gender biases as well as an unexplained variation over time suggesting that IQ was continually increasing in the population. Gardner (1999), suggesting that intelligence is modular and relates to the ability to solve problems in different domains, proposed a set of criteria by which an intelligence could be identified, yielding originally seven, and more latterly, eight different intelligences. However, he concluded that SQ should not be included in the list since its content was too broad and too problematic (Gardner, 2000). It is perhaps also not clear as to what distinct “problem” SQ addresses. Goleman has done much to popularize the notion of Emotional Intelligence (EI), however 15 years since publication of his original model the field appears to have diverged with continued controversy as to the content of the model, the adequacy of its measurement, and its ability to predict work success. To the extent that there is little agreement about EI as a construct, we may be concerned that SQ is likely to have similar problems. In short, to join the two concepts together is to make a number of assumptions about both, including that they both relate to some aspect of mental functioning.

The conceptual difficulties with the notion of Spiritual Intelligence suggest that its definition and operationalisation in the form of a model is likely to be hard to justify on anything but intuitive and/or pragmatic bases. Nevertheless a variety of definitions and models of SQ do exist. Wigglesworth very clearly defines SQ as “the ability to behave with Wisdom and Compassion while maintaining inner and outer peace (equanimity) regardless of the circumstances.” Interestingly, this definition is separate from her definition of Spirituality which she defines in terms of human need: “an innate human need to be in relationship with something larger than ourselves—something we consider to be divine, sacred or of great nobility.” From my own perspective, neither definition is very satisfactory. SQ is firmly brought into the territory of intellectual and emotional capability in terms of “Wisdom” and “inner and outer peace” and is thus somewhat split off from notions of transcendence, whilst on the other hand, the definition of Spirituality has a religious quality underpinned by the assumption of a psychological need to relate to some non-material entity. I would have liked to have seen Wigglesworth’s definition of SQ somehow relating to a set of skills contributing to the achievement of Spirituality, but I cannot see the link, at least not at this level. By contrast, King (2008) puts forward an alternative definition of SQ as “a set of mental capacities which contribute to the awareness, integration, and adaptive application of the nonmaterial and transcendent aspects of one’s existence, leading to such outcomes as deep existential reflection, enhancement of meaning, recognition of a transcendent self, and mastery of spiritual states”. But this definition leaves open the question of what might constitute “spiritual states”, and hence contains a circularity.

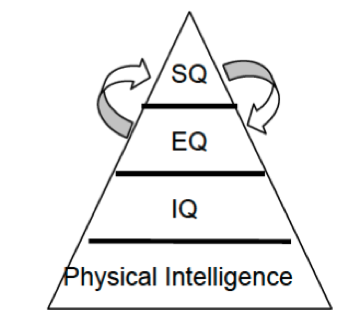

Wigglesworth also proposes a model of developmental hierarchy in intelligences in pyramid form with Physical Intelligence at the base and SQ at the apex.

This diagram bears a striking similarity to Maslow’s hierarchy, where the various intelligences serve to satisfy needs at the relevant level, and therefore points to SQ as the means to satisfy man’s need for self-actualization. I confess to finding the reformulation of SQ as Self-Actualization Intelligence, an attractor state geared towards solving the problem of self-development and the realization of one’s highest potential, distinct from, but linked to all other types of intelligence, very attractive. Commons and Funk, in their review of Irwin (2002): “Human Development and the Spiritual Life: How Consciousness Grows toward Transformation” discuss the dichotomy of two different views of spiritual development: (1) that it comes “on top of” normal postformal cognitive development or (2) that it is a parallel line. The former view would suggest that one cannot develop spiritually until one has already reached a certain stage of cognitive development, thus rendering SQ out of reach of a large percentage of the population. The latter view offers more hope and seems to make greater allowance for spiritual experiences in people who are not well developed in IQ or EQ, for example, children. Wigglesworth states that she sees SQ as a separate line and “representing interdependency of multiple lines” whilst also acting as “capstone” dependent on other forms of Intelligence (specifically EQ) and also enhancing them. I imagine SQ as both a parallel line and coming on top of other forms of intelligence, whilst growing in significance as a person develops. Such a notion might also help explain the different ways people at different levels of social-emotional and cognitive development describe the spiritual aspects of their lives.

The Model Itself

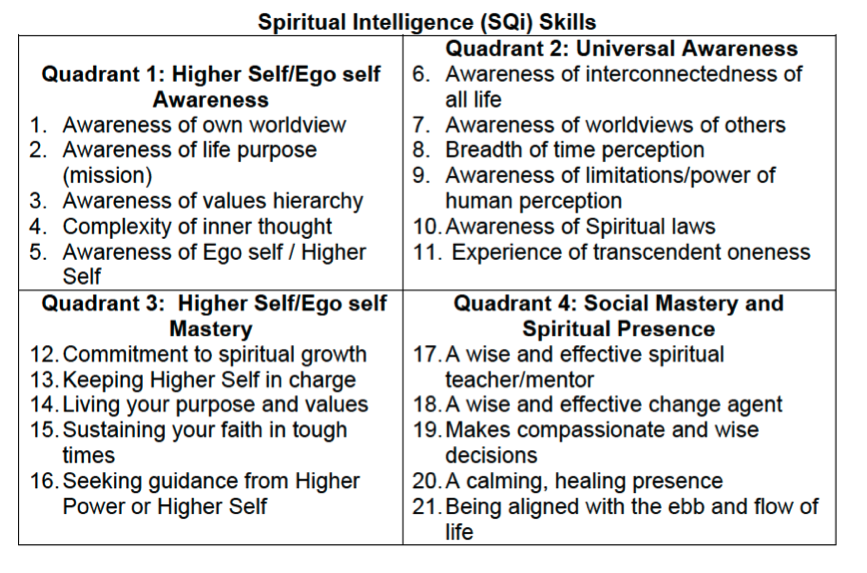

Wigglesworth emphasises the behavioural nature of her definition of SQ and posits 21 skills that underlie that behavior. These are grouped along two dimensions, self-other and awareness-mastery, falling into 4 quadrants that mirror those of Goleman’s EQ.

For each skill, Wigglesworth has defined 5 levels of attainment, making 105 descriptors in total. My understanding is that these skills are designed to map closely onto Cook-Greuter’s (1999) descriptions of action-logic or ego-development stages from Impulsive to Ironist. If so, then I liken this model of SQ to be an elaboration of Cook-Greuter’s development stage model by separating out a “spiritual” line. Using the 105 descriptors, a self-report measure using a Likert scale (the SQi) has been created and piloted, and is now available to the general public on line. The self-report questionnaire takes about 25 minutes to complete after which a developmental report is emailed to the participant with suggestions for practices that might raise the SQ.

For the sake of contrast, we can compare Wigglesworth’s model with those of Amram (2007) and King (2008). Amram’s model was derived from thematic analysis of interviews with people designated as spiritually intelligent by their colleagues. The seven themes are:

- Consciousness: Developed refined awareness and self-knowledge;

- Grace: Living in alignment with the sacred manifesting love for and trust in life;

- Meaning: Experiencing significance in daily activities through a sense of purpose and a call for service, including in the face of pain and suffering;

- Transcendence: Going beyond the separate egoic self into an interconnected wholeness;

- Truth: Living in open acceptance, curiosity, and love for all creation (all that is);

- Peaceful surrender to Self (Truth, God, Absolute, true nature); and

- Inner-Directedness: inner-freedom aligned in responsible wise action.

King (2008) puts forward a theoretical four-category model:

- Critical Existential Thinking

- Personal Meaning Production

- Transcendental Awareness

- Conscious State Expansion

The inclusion of existential thinking mirrors Gardner’s (1993) description of “the intelligence of big questions” and relates to the contemplation of the nature of existence—a philosophical theme. Personal meaning production relates to the quest for meaning, and is seen as an ability to find meaning and purpose in life. Transcendental awareness relates to the capacity to identify dimensions of the self, others and the physical world that transcend normal material human experience. Finally, conscious state expansion relates to the ability to move into different “higher” states of conscious awareness, for example, those achieved by skilled mediators, potentially measurable by EEG scans.

There are clearly quite a lot of common themes and overlaps in these models. As for differences, it seems to me that Wigglesworth’s category of Higher Self/Ego awareness appears somewhat more specific than either Amram’s theme of “Consciousness” or King’s notion of Critical Existential Thinking. For me, the general notion of a dichotomy between ego and higher self is somewhat restrictive, unless its resolution occurs at what I take to be Kegan’s (1982) and Laske’s (2006) notion of the self-authoring mind, able to construct for itself a “theory” or narrative of the self that provides meaning. But that would position the skills of that quadrant rather firmly at people between Kegan’s stages 3 to 4. Similarly, Wigglesworth’s “Universal Awareness” quadrant appears to be a more specific definition of King’s Transcendental Awareness category, incorporating certain conceptions about time and knowledge of spiritual laws. Quadrant 3, Higher Self/Ego self-mastery resonates strongly in my mind with emotional intelligence competencies of self-management, partially overlapping with Amram’s notion of “Grace”, but also reflecting a strong self-development motivation. Finally, Quadrant 4, Social Mastery and Spiritual Presence, very much relates to the occupation of some kind of leadership role, and thus is not strongly represented in either Amram’s or King’s models.

In summary, Wigglesworth’s model appears to include elements of emotional intelligence and leadership skills not covered in the other models, but in other respects is pretty similar. Whether it is correct to consider all of these elements as either spiritual or intelligences is up for debate depending on how narrowly or broadly one chooses to use such terms.

Validity and Reliability

What would a good measurement test of SQ look like? First there is the issue of whether a self-report questionnaire is likely to be valid and reliable. Whilst many self-report personality questionnaires have well-established reliability and validity, it is harder to validate self-report measures of emotional intelligence because the constructs involved are more subjective and less stable. In addition, it can be argued that respondents are inclined towards “socially desirable” responses in such questionnaires. From a theoretical perspective the danger is that respondents “espouse” positions that they are not presently able to live up to. The SQi questionnaire does not have inbuilt controls for such faking, however two questions have been included to check whether people felt they had responded honestly and factored in how other people might see them.

In the UK, published psychometric tests are peer reviewed to check that they meet minimum standards. If a test meets such standards, it can be registered and the peer review ratings on a variety of measures are published. It is not in the scope of this article to make such an exhaustive review, but Wigglesworth has been generous in sharing her research studies, which are shortly to be published. Hence I can comment on some measures.

Typically, test publishers present studies to show reliability and validity of their tests. Reliability is commonly measured in terms of “test-retest” and “alternative forms” statistics. The issue is the extent to which a respondent might score the same if taking the test at two different times or in two different forms. Wigglesworth’s research does not yet cover such assessments. Validity is typically measured in terms of construct validity and criterion validity. In the former, the question is the extent to which a test conforms to the theory of what it is trying to measure. In the latter the question is the extent to which scores on the test predict other measures of the concept Spiritual Intelligence.

Currently the research studies consist of

- An initial alpha pilot using “experts” to refine the content of the items,

- A beta pilot using a larger and more diverse sample of respondents,

- A workplace pilot focused on outcomes,

- A criterion validation study in 2005 with a sample of 230 people,

- A correlation study against Cook-Greuter’s ego-development sentence, and

- A completion test with a sample of 139 people.

Whilst all the studies are of interest, my view is that only study number 4 qualifies as relevant for review in that it alone contains sufficient data to analyse aspects of construct and criterion validity. The study was conducted by asking 230 people to take the SQi and also complete 9 essay questions asking them to describe various aspects of their spiritual life. This amounts to a concurrent validity study albeit using two different self-report measures. The essay responses were coded and scored on a scale of 0-5 rating the level of skill. These scores were then correlated against the scores for the skills as rated in the SQi questionnaire. High and significant correlations were seen throughout, indicating that people who reported themselves as having high levels of skill in the questionnaire, also did so in answer to the essay questions. This result certainly validates the questionnaire as a proxy for essay questions, but clearly does not conclusively validate the questionnaire as a predictor of Spiritual Intelligence in the eyes of a 3rd party observer.

Interestingly the highest correlations were achieved between the overall score on the SQi and the essay question “Describe how your spiritual side impacts others around you”, while a much lower correlation was achieved with the question “Describe your own spiritual beliefs and how they relate to the beliefs of others”. The reason for this is not clear. It might have been an artefact of the scoring system. Alternatively it might reflect a high degree of “espousal” in that people describe themselves as spiritual and having a high degree of impact on those around them, but are less able to articulate their belief system or to compare it with those of others.

Another useful set of data comes from the correlations between scores on individual items in the questionnaire. Factor analysis shows a single factor to be at work here, lending support to the idea that Spiritual Intelligence is a unitary construct. However, some of the correlations are very high, suggesting some redundancy in the questionnaire in terms of overlapping items. Wigglesworth theorises that the Quadrant 1 skills (Higher self/ego awareness) are “foundational”, i.e., that they are the basis on which the skills in the other quadrants are developed. That being the case, I would have expected to see higher correlations between 1st quadrant and 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quadrant skills than between 2nd and 3rd or 2nd and 4th (for example). Eyeballing the data the correlations all seem to be very similar. Hence the data provides some, but not particularly strong, support for construct validity.

A limitation of the study is that the respondent sample was predominantly white, middle-aged, and relatively wealthy. There was only one significant relationship between the scores on the SQi and a demographic category—that of religious affiliation. Jewish individuals have significantly higher scores on the SQi (including individual skills) than other religions. Hindu and those reporting no or other religious affiliation showed second highest scores, and Christian-affiliated subjects followed closely. Catholic-affiliated subjects showed the lowest scores on the SQi. It remains to be seen as to whether this bias is maintained in other samples. If so it could become a serious limitation since it might suggest that the way different cultural groups view and describe their spiritual experience influences their score.

Lastly it is worth commenting on the 5th study, which compared scores on Cook Greuter’s sentence completion test measuring level of ego development with scores on the SQi. The chart below shows the range of scores, and mean score on the SQi for each stage of adult ego development.

There is a clear increase in mean score on SQi through progressive ego development stages. Wigglesworth suggests that the SQi could therefore have value in predicting the stage of adult development. But notice how scores between 60 and 80 on the SQi were well within the range of scores on 5 separate ego stages, and how scores of 80 to 85 were within the range on 6 separate ego stages. On that basis given a single score, the possibility of that individual being at any particular stage might not be something worth betting on.

A final question that this study raises relates to the idea of SQ being either a separate line or coming “on top of” later stages of development. In as much as this instrument measures Spiritual Intelligence, the data suggests that it runs in parallel with stages of development from Diplomat. However, this does not necessarily entail that what is being measured is a separate line—a close correlation with developmental level suggests that it could well be part of the same construct.

Conclusions

Wigglesworth’s SQi appears to be the most thoroughly researched and tested measure of Spiritual Intelligence available. It fits neatly alongside the maps provided by Wilber’s AQAL, Goleman’s EQ, and Cook-Greuter’s ego-development levels. It is also similar to other models and conceptions of the construct. The psychometric properties of the questionnaire are not yet fully assessed and documented and its applicability to more culturally diverse samples outside of the U.S. is unknown. However, more data will no doubt be available in time.

As a product, the SQi seems to be targeted principally but not exclusively at an audience within a business community, somewhere between Stage 3 and Stage 4 in Kegan’s terms. For some, it may prove to be an excellent developmental tool, providing guidance on areas where spiritual or spiritually-related practices might enhance well-being. For others, it may still be seen to be conceptually flawed and inadequately proven. To her credit, my sense is that Wigglesworth does not pretend that she has “the answer”. More accurately, she offers her work as hypothesis for others to check out for themselves and is keen to add more research evidence. In the great tradition of North American self-help teachers, she has created a tool for which there may well be a strong market. The big assumptions underlying her offering are the idea (following Kegan) that higher levels of development (however described) are necessarily better for all concerned, and the notion that such higher levels can be reached by learning and practicing certain “skills”. I anticipate that there might be some risks for some people embracing this model in that, pursuing higher and higher levels of “skill”, they over-reach themselves developmentally—which is to say that they may try to embrace practices that only someone at Kegan stage 5 and above can master.

For my part, the reduction of the “Spiritual” into a common set of staged “skills” and their reproduction as kind of commodity product somehow cuts across my sense of spiritual matters being personal, ineffable, and beyond explanation. At the London Integral Circle’s July salon Oliver Robinson constructed a dialectical notion of spirituality citing seven dimensions in which it sits in opposition to our notion of science. In this view, as much as the “head” tries to rationalise the concept, it remains in the unfathomable province of the “heart”. Dialectically therefore, one might argue that the spiritual is nothing other than what is not known and understood, and which has yet to take form. There is also the view that one’s notion of the spiritual is itself stage-related (Wilber 2006, Laske 2006) acquiring more depth and richness as a person develops. That being the case, any attempt to develop another person’s spiritual intelligence might need first to take into account where that person is on other measures of adult development and could most likely not be achieved by someone developmentally at a lower level. Here we start to come closer to the thinking of Eastern traditions where the focus is on creating the conditions that might foster spiritual development in oneself and others rather than pursuing development itself (Brazier, 2003).

On a final note, some may have a concern that the commercial exploitation of peoples’ desire to climb the developmental ladder by offering a “spiritually” branded product is not a worthy cause, what Gelfer (2010) refers to as the “Indigo dollar”. I imagine some spiritually oriented groups might see this product and its promotion as exploitative. I also imagine that some specialist psychometricians might frown at the credibility and depth of the research. But it is also true to say that throughout human history, people have packaged belief systems that purport to help people come to terms with themselves and their humanity and traded these for money. Although science appears progressively to demystify the territory of the human mind, I suspect that there is yet plenty of territory that will remain unexplored and unknown for a long time to come. Where matters of the spirit are concerned, to quote an old English adage, “at the end of the day, you pays your money and you takes your choice”.

About the London Integral Circle:

The circle meets regularly usually on the first Wednesday of every month. For details see: http://www.integralstrategies.org/london.html

E-Group discussion and news can be found at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Londonintegralcircle/

References:

Amram, Y. (2007) The seven dimensions of spiritual intelligence: An ecumenical, grounded theory. Paper presented at the 115th Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA.

Brazier, C. (2003) Buddhist Psychology. London: Robinson.

Cook-Greuter, S. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2000). A case against spiritual intelligence. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10, 27-34.

Gelfer, J (2010) “LOHAS and the Indigo Dollar: Growing the Spiritual Economy” New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry. Vol. 4, No. 1 (October 2010) Pp. 48-60

Goleman, D (1996) Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ Bantam Books

Irwin, R, (2002) Human Development and the Spiritual Life: How Consciousness Grows toward Transformation; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York. Reviewed by Commons, M L and Funk, http://www.dareassociation.org/Papers/Irwin%20Review.htm

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

King B (2008) “Rethinking claims of Spiritual Intelligence: A definition, model, and measure.“ Masters Thesis, Faculty of Arts and Science, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada

Laske, O. (2006). Measuring hidden dimensions: The art and science of fully engaging adults (Vol. 1). Medford, MA: IDM Press.

Meyerhoff, J. (2010) Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber’s Theory of Everything. LaVerne, Tennessee: Inside the Curtain Press.

Raven, J., Raven, J.C., & Court, J.H. (2003, updated 2004). Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment

Sternberg, R. J. (1985): Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. New York, Cambridge University Press

Wilber, K (2000) Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. 2nd ed. Boston: Shambhala

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston: Shambhala

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality: A startling new role for religion in the modern and postmodern world. Boston MA: Integral Books.

About the Author

Nick Shannon is the founder and principal of Management Psychology Limited, a UK based practice specializing in organizational and management development. Nick is a Chartered Psychologist, a member of the British Psychological Society and a founding member of the Association of Business Psychologists. After studying Psychology and Philosophy at Oxford University, Nick’s career has involved working variously as a commodity and derivatives trader, a director of a foreign exchange business, and a restaurateur. Latterly a business consultant, Nick’s goal in working with clients is to help them improve the quality of their management teams, which he believes leads to better organizational performance and more satisfied and engaged employees. Typical assignments involve the design and delivery of assessment, selection and development processes at three points of focus: individual leaders; senior management teams; and organization-wide.

Nick

Thank you for a balanced and inclusive article on this topic . Having recently read “The Master & his Emmissary” I am left wondering if this journey of the spirit is for us in the Western world more about reconnecting with the RH side of our brains which metaphorically we often refer to as “heart”

Sol

Hey, I am Anubhav Kapoor, a Leadership Researcher.

These leadership attributes (in your blog) co-relate with Spiritual Intelligence (SQ) Dimensions.

Spiritual Intelligence and Business Leadership (Survey Questionnaire)

An honest response to this survey is expected!!

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/viewform?formkey=dGppcjV0Vjg5emF3YVo5U2N6bEJDRFE6MQ