Scott Lichtenstein

Introduction: We’ve Been Practicing Leadership for Over 6,000 Years; What Else Do We Need to Know?

The Pharaohs leading the cadres managing the work teams that built the pyramids understood leadership (Dade 2008). The Imperial Emperors knew how to lead the Chinese civil service that held China together for thousands of years. The Moguls of India and their administrators understood how to lead. The Holy Roman Empire needed no leadership books or journal articles. Leadership as practised by the Egyptian Pharaohs and Chinese emperors still lives with us in our language today: “stepping out of line” and “getting the chop” referring to the soldier of the emperor and Pharaohs with a sabre on horseback that would chop off the head of anyone who literally stepped out of the single file line of workers.

More recently, the rise of professional management in Western economies has perpetuated a plethora of lessons in leadership. From Al “Chainsaw” Dunlop to “Neutron Jack” Welch, CEO of General Electric, one of the most successful corporations in the world, they all knew about leadership. Voted by Fortune magazine as Manager of the Century, “Neutron” Jack gained the nickname of the mythical bomb that killed people but left buildings standing by shedding 112,000 people in the beginning of his tenure, but left the factories they worked in still standing.

From the Egyptian Pharaohs in their temples to the glass palaces of the Masters (Bastards?) of the Universe on Wall Street, they all had the same approach to leadership. Dade (2008, p. 1) summed up this sentiment by stating, “It’s my way or the highway”. Further, “The use of hierarchical top-down power structures that institute a system of policies, procedures and programmes to ensure delivery of products and processes in a manner consistent with stated objectives. By any measure of success this works and in so doing has created the basis of our modern world”.

If the “my way or the highway” school of leadership has been working for thousands of years, why is the subject of leadership under such scrutiny? If we know the tried and tested “my way or the highway” approach to leadership works, why are there approximately 3,000 books a year written on the topic? One major reason is due to changing employees’ values, and in the aggregate, societal values. Societal values have changed and individuals with developmentally leading edge values have gotten into leadership positions and have changed policies and procedures. Without too much difficulty I’m sure you can think of at least one organisational policy that exists today that would have been unthinkable 40 years ago. Equally important, the values of followers have changed.

This article focuses on the role of values in leadership and how this unconscious and invisible force creates or stymies visible results. First, the impact of values on leaders is outlined and is followed by an examination of the link between leaders’ values and value creation. The concept of the values dynamic is introduced and illustrated by two mini-cases of leaders from Hewlett-Packard and 3M to show how the dynamic between the values of a leader and the culture impact sustainable performance. Next, why leaders and followers do what they do, based on research examining managers’ and leaders’ needs and values is discussed, and the mapping of an executive team’s values provided to offer a practical example of how these woolly concepts can be measured and used for deep dialogue to facilitate leadership and team development.

If societal and employees’ values have changed, in what ways do values impact leadership?

1. The Impact of Values on Leaders

Personal values impact leaders in at least two ways: 1) as a perceptual filter that shapes decisions and behaviour, and 2) as a driver of their methods of creating value.

1.1 Values as Perceptual Filters

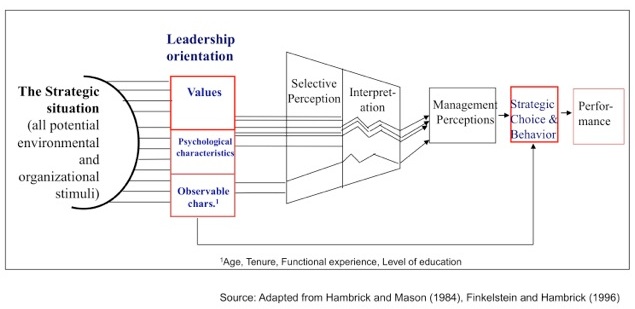

Hambrick and Mason’s (1984) Upper Echelon Theory and Finkelstein & Hambrick’s (1996, p. 54) extension to it (as seen in figure 1) provide a theoretical model that illustrates that personal values act as a perceptual filter for how leaders perceive the external environment and shape strategic choice, behaviour, and ultimately organisational performance.

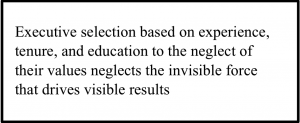

In a study of 163 owners, senior and middle managers, Lichtenstein (2005) empirically operationalized the Values, Observable characteristics, Strategic choice & behaviour, and Performance elements of the Upper Echelon Theory. He found that executive values had a direct and significant impact on organisational performance, whereas age, tenure,  functional experience, and level of education did not. This finding indicates that personal values are a more fundamental leadership attribute than the age, tenure, functional experience, and level of education in the process of how leaders influence organisations. Executive selection based on age, experience, tenure, and education to the neglect of their values ignores the invisible force that drives visible results.

functional experience, and level of education did not. This finding indicates that personal values are a more fundamental leadership attribute than the age, tenure, functional experience, and level of education in the process of how leaders influence organisations. Executive selection based on age, experience, tenure, and education to the neglect of their values ignores the invisible force that drives visible results.

Moreover, in a study of 75 in-work MBA managers, Higgs and Lichtenstein (2010) found no relationship between psychological traits based on the leadership “Big 5” five-factor model of personality (McCrae and Costa 1997) and personal values. This result highlights that “psychological characteristics” and “values” suffer from the “jingle fallacy” (Kelley 1927): “psychological characteristics” and “values” sound similar so they are lumped together. Values and personality traits are complementary but separate and distinct attributes of leaders and must be treated as such.

1.2 Values as a Key Element of Strategy

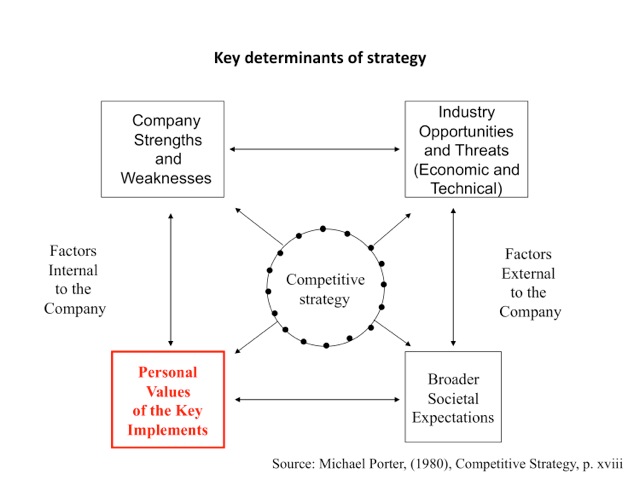

Leadership is not solely about making people feel good, but includes profit and loss responsibility, achieving operational and financial performance, and developing strategy. The personal values and aspirations of senior management have been identified by Porter (1980) as a key component of competitive strategy (see figure 2) but have been neglected by the field. Finkelstein and Hambrick (1996, p. 48) recognised the research void that exists in the examination of strategic leaders’ values and their relationship with strategy, noting, “Even though values are undoubtedly important factors in executive choice, they have not been the focus of much systemic study.”

Why has so little research been done in the area of values and its relationship to strategy despite values being identified as critical to strategy formulation and implementation? In part because there was no theory to understand this until  Hambrick and Mason’s Upper Echelon theory arrived four years after Porter’s work. Also, the tools and techniques to measure values didn’t exist until relatively recently. This will be illustrated in the last section of this article. A lack of access to leaders allegedly not willing to have their values examined is also cited as another reason. In short, the field has focused on the difficult elements of strategy rather than the more challenging elements, and values are a more challenging element. Effective leaders know they need to focus on the difficult and the challenging elements of strategic leadership.

Hambrick and Mason’s Upper Echelon theory arrived four years after Porter’s work. Also, the tools and techniques to measure values didn’t exist until relatively recently. This will be illustrated in the last section of this article. A lack of access to leaders allegedly not willing to have their values examined is also cited as another reason. In short, the field has focused on the difficult elements of strategy rather than the more challenging elements, and values are a more challenging element. Effective leaders know they need to focus on the difficult and the challenging elements of strategic leadership.

1.3 Values, Vision and Value Creation

Business now almost universally accepts that the primary leadership task is value creation for shareholders and stakeholders. This is especially true in the midst of an era when we’ve seen leaders’ and directors’ remuneration, stock options, and payoffs disconnected from company performance, and in some cases, value destruction. Since the bubble burst in 2007, one leadership lesson we’ve learned is that motive matters, which surely is at the heart of the current zeitgeist. The spotlight has been turned on leaders by their organisation’s stakeholders who are asking, “leadership for whose benefit?” and “value created for whom?”

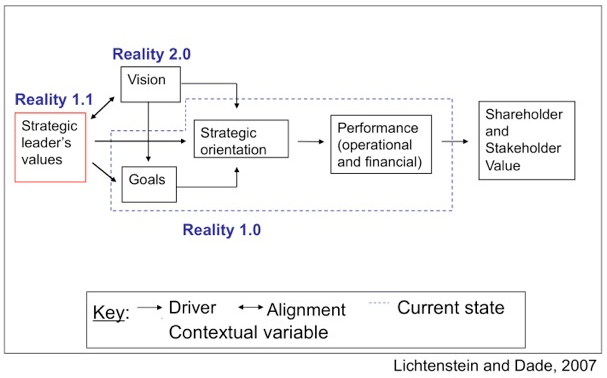

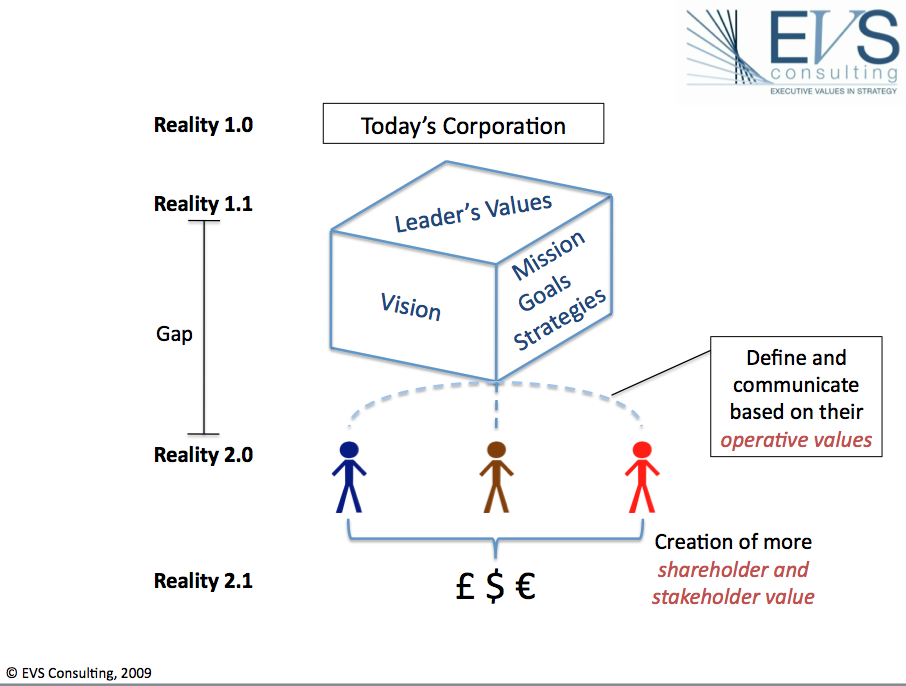

The needs and values of strategic leaders shape their vision to create (or destroy) value. By uncovering these drives, leaders can motivate the workplace culture to implement strategies further and faster in the organisation. The conceptual framework in figure 3 illustrates that a leader’s values are antecedents of vision in service of creating value for shareholders and stakeholders.

Lichtenstein and Dade (2007) refer to a chief executive’s motives for action and values as Reality 1.1. This is because it is the lynchpin of aligning the existing culture. that we refer to as “Reality 1.0” with the vision – the future state of the organisation – that we refer to as “Reality 2.0”[i]. Sustainable above average performance and value creation is achieved through aligning Reality 1.0, i.e., the organisation’s mission, goals, objectives, strategies, and tactics to Reality 2.0, the vision.

The values dynamic is the exchange process between the values of the CEO and the rest of the organisation, i.e., the culture. Leaders create or destroy value to the extent that they align Reality 1.0 with Reality 2.0 by implementing their methods of creating value (missions, goals, and strategies) further and faster throughout the organisation. But individual leaders can’t create and sustain the leadership required to align and shift an organisation: a vision that isn’t shared is an unrealised dream; a strategy without organisational commitment is a delusion.

Examples of values dynamic misalignment and alignment are briefly illustrated in the mini-cases of ex-CEO Carly Fiorina’s alignment of her vision for creating value at Hewett Packard (HP) in comparison with her successor Ex-CEO Mark Hurd, and James McNerney ex-CEO of 3M versus his successor CEO George Buckley. These cases contrast the dynamic between the leaders’ values and that of the organisations and the impact on aligning or misaligning their methods of creating value with the culture.

Hewlett-Packard

Fiorina served as chief executive officer and chairman of Hewlett-Packard from 1999 to 2005. In 2005, she was forced to resign following differences with the board of directors about how to execute HP’s strategy. Ex-CEO Mark Hurd was CEO from March 2005 and resigned in August 2010. The company is renowned for its egalitarian, decentralized culture that came to be known as “the HP Way.”[ii] This involved one of the first all-company profit-sharing plans that gave shares to all employees, and offered tuition assistance, flex time, and job sharing.

Research carried out by Waters (2008) into how leaders’ values impact decision-making compared managers’ perceptions of ex-CEO Carly Fiorina and ex-CEO Marc Hurd. Regarding Fiorina, a common perception amongst managers was that there was a values mismatch with the culture:

“People talked about the HP Way a lot and Carly came along and brushed that under the carpet a bit and people didn’t like her for that.” (Manager 1)

“I was never at all sure, other than her desire to be showbiz, quite what her values were.” (Manager 2)

“With Carly Fiorina there were corporate values articulated and examples of things done by Carly which were disconnected and I think that is what made a lot of people feel uncomfortable.” (Manager 3)

In contrast, managers felt Mark Hurd did a far better job at aligning his method for creating value to the culture summarised by one manager:

“I do feel he (Mark Hurd) is more mapped to the basic core values of HP than Fiorina was; his wishes for operational tightness, profitability, and cost control are pretty much the same as the values fifty years ago”.

3M

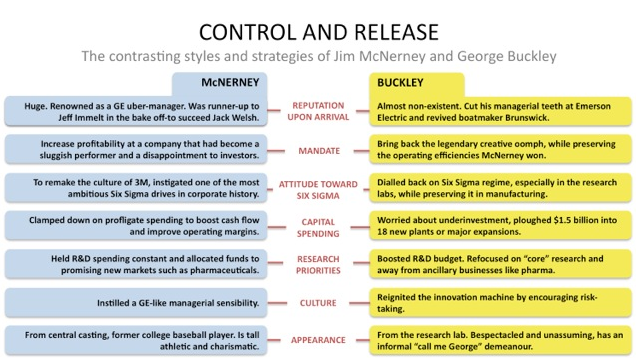

Prior to joining 3M in 2001, James McNerney competed with Bob Nardelli and Jeff Immelt to succeed the retiring Jack Welch as chairman and CEO of General Electric. When Immelt won the three-way succession race, McNerney left GE and joined 3M from 2001 to 2005, holding the position as chairman of the board and CEO. Sir George William Buckley was named chairman and CEO of 3M in December 2005 following the departure of McNerney who left abruptly to join Boeing.

3M’s creative culture that once gave rise to the “Post It Note” phenomenon prided itself on drawing at least one-third of sales from products released in the past five years, and was underpinned by the “3M Way” that includes:

(i) Workers can seek out funding from a number of company sources to get their pet projects off the ground,

(ii) Official company policy allowing employees to use 15% of their time to pursue independent projects,

(iii) Ideas like the Post It Note are allowed to be fiddled with for several years before the product goes into full production, and

(iv) The company explicitly encouraged risk and tolerated failure (Hind, 2007).

Sound like Google?

The paper by Hind (2007) “At 3M, A struggle between Efficiency and Creativity” explains in-depth the changes wrought by McNerney and contrasts them with those made later by Buckley. When McNerney joined, “he had barely stepped off the plane before he announced he would change the DNA of the place” (Hind 2007, p. 1). McNerney began by implementing the GE playbook; axing 8,000 workers (about 11 percent of the workforce), intensifying the performance-review process, cutting spending and importing GE’s Six Sigma program – a series of management techniques designed to decrease production defects and increase efficiency. Thousands of staffers became trained as Six Sigma “black belts”.

The focus on efficiency began driving out the innovation culture. Remembering a meeting at which technical employees were briefed on the new Six Sigma process, Michael Mucci, a 27 year veteran at 3M recalls, “We all came to the conclusion that there was no way in the world that anything like a Post It Note would ever emerge from this new system” (Hind, 2007, p. 2). The Post It Note inventor, 3M scientist Art Fry, reflecting on McNerney’s culture change programme observed, “What’s remarkable is how fast a culture can be torn apart. [McNerney] didn’t kill it, because he wasn’t here long enough. But if he had been here much longer, I think he could have” (Hind, 2007, p. 3).

Upon McNerney’s departure, new CEO Buckley reinvigorated the workforce by reversing McNerney’s legacy and getting back to the “3M Way” by scaling back on Six Sigma, boosting R&D spending, and rewarding risk taking. Reflecting on the process-focused approach of the past, Buckley remarked, “Perhaps one of the mistakes that we made as a company – it’s one of the dangers of Six Sigma – is that when you value sameness more than you value creativity, I think you potentially undermine the heart and soul of a company like 3M” (Hind, 2007; p. 3). Tim Hammond, the director of strategic business development, states, “[Buckley] has brought back a spark around creativity.” Bob Anderson, a business director in 3M’s radio frequency identification division adds, “We feel like we can dream again” (Hind, 2007, p. 3). A contrast of the two leaders is found in figure 4.

What are the leadership lessons of these two mini-cases? One relates to leaders and the other to boards of directors.

Leaders need to recognise that their values shape their strategy preferences, which influence the organisation’s culture that is termed the “values dynamic”: the dynamic between the leaders’ values and those of the employees. Leaders need to understand the dynamics of their underlying needs and values (Reality 1.1), and that of the culture (Reality 1.0). Managers manage from their own values, but leaders have to lead a whole culture. Therefore, they need to be aware of the diversity of values in organisations if they want their visions to become reality and their value creation methods to be implemented. Leaders like Fiorina and McNerney who try to bend cultures to satisfy their own needs and values without understanding the values embedded in the organisation will struggle to align the company to their vision and to create long-term value for shareholders and stakeholders

|

|

Regarding corporate governance, boards that become budget-driven rather than strategy-led are liable to appoint CEO’s to boost short-term performance who may not understand the culture or values dynamic, which is bound to stymie their attempts to create value in the long term. The ultimate strategic decision is appointing the right chairman and chief executive whose methods of creating shareholder and stakeholder value will support the culture (Taylor, 2010).

Regarding corporate governance, boards that become budget-driven rather than strategy-led are liable to appoint CEO’s to boost short-term performance who may not understand the culture or values dynamic, which is bound to stymie their attempts to create value in the long term. The ultimate strategic decision is appointing the right chairman and chief executive whose methods of creating shareholder and stakeholder value will support the culture (Taylor, 2010).

1.4 Effective Leadership that Creates Value

Boards would do well to remind themselves of the lessons of leadership and sustainable value creation. The only longitudinal study of the link between leadership teams and corporate performance is Collins’ (2001) “Good to Great”. He tracked 1,435 Fortune 500 listed companies from 1965 and found:

• 11 made the transition from good to great (outperforming companies in their sector), and

• High profile larger-than-life CEOs, correlate negatively with the progression from good to great.

The study of successful CEOs shows two vital qualities (Collins, 2001):

1. HUMILITY – being self-effacing and arrogance free, and

2. WILL – persistence in the pursuit of business goals.

“Quiet leadership” was the norm: leaders that created value over the long term dedicated themselves to building the organisation rather than their CVs, with an emphasis on starting with the RIGHT TEAM rather than the right project, product, or even industry.

“Quiet leadership” was the norm: leaders that created value over the long term dedicated themselves to building the organisation rather than their CVs, with an emphasis on starting with the RIGHT TEAM rather than the right project, product, or even industry.

Having examined the ways in which leaders’ needs and values impact organisations and the relationship between culture and methods of creating value, the next section examines what is directing the thoughts and emotions, and shapes the behaviour of leaders and others.

So what moves leaders and others to action?

2. Why Do Leaders (and Followers) Do What They Do?

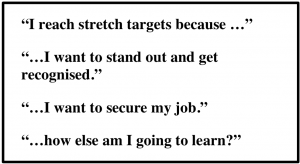

Understanding why people do what they do necessitates investigating the forces that drive behaviour, because people engage in the same behaviour but for very different reasons.

Clearly, if we want to influence the behaviour of others, we need to understand what is already influencing them. By the end of this section, you should be able to identify the different drivers expressed in the three statements regarding hitting stretch targets. As leaders, we can’t change what drives people – their values – but we can change their behaviour by understanding those forces and tapping and harnessing them through policies, strategies, and communication.

Clearly, if we want to influence the behaviour of others, we need to understand what is already influencing them. By the end of this section, you should be able to identify the different drivers expressed in the three statements regarding hitting stretch targets. As leaders, we can’t change what drives people – their values – but we can change their behaviour by understanding those forces and tapping and harnessing them through policies, strategies, and communication.

As long ago as 1961, Gordon Allport suggested that value priorities are the “dominating force” in life as they direct all of an individual’s activity towards the achievement of his or her needs. Values can be considered emotional states we either go towards or away from, which are directed towards individuals’ underlying needs.

From Values to Value Systems

The understanding of, and previous research into values has suffered from a focus on individual values that:

(i) result in low reliability (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1987; Schwartz, 1996);

(ii) ignore equally or more meaningful values (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1987, Schwartz, 1996); and

(iii) ignore the premise that individuals make trade-offs among competing values according to their values priorities (Allport, 1955; Hambrick & Brandon, 1988; Maslow, 1970; Rokeach, 1979; Schwartz, 1996).

Individuals’ values priorities underscore a critical characteristic of values: they are organised in a hierarchical system ordered by relative importance to one another (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1987; Maslow, 1970; Schwartz, 1992; Rokeach, 1979). Although there are universally held values, an individual, and in the aggregate, groups, will espouse a dominant set of values. “At the top of each person’s system are a small handful of dominant values of paramount importance” (Brandon & Hambrick, 1988, p. 6). Therefore, a dominant value system exists for each person that is more important to understand than single values (Brandon & Hambrick, 1988; Rokeach, 1979; Schwartz, 1996).

2.1 Needs, Values, or Levels of Consciousness?

Editor’s note – Readers of the Integral Leadership Review will most likely be familiar with Beck and Cowan’s “Spiral Dynamics” model of “levels of consciousness” based on the work of Clare Graves. This paper presents, as an alternative, research centred on the work of Abraham Maslow, whose hierarchy of needs model has received broader academic interest. Maslow and Graves were contemporaries whose theories have both similarities and differences. Of the two, Graves’ theory is perhaps the more complex, focusing on the dynamic interaction between the individual and his or her environment and therefore placing more emphasis on the context in which a person comes to value certain things. It might be considered, for example, that Graves saw the possibility that a personal hierarchy of needs can exist at, and within, different levels of consciousness and that the means by which a person chooses to satisfy those needs will be different at different levels. However, for the purpose of research within a particular society and culture, arguably it is more straightforward and parsimonious to apply Maslow’s model, which can be operationalized with greater simplicity and reliability.

From a research perspective, Maslow’s theory can be empirically tested using statistically reliable instruments, such as Rokeach’s Value Survey, Kahle’s List of Values and the proprietary instruments of Stanford Research International’s Values and Lifestyles (VALS) and CSDM’s Values Modes (Baker 1996), whereas the Spiral Dynamics model is considerably harder to test and has consequently received much less academic interest. In particular the higher levels (yellow and turquoise) of the Spiral Dynamics model present difficulties when defining parameters with which to test for their presence. Readers will no doubt however notice some similarity and overlap between the categories of needs found in this research and descriptions of the blue, orange, and green levels in the Spiral Dynamics model.

Maslow (1943) presents a model of human psychological development that facilitates understanding of the basis of human values and the way they can change over time from birth to death. His observations and qualitative research led him to the insight that human beings are all born with a set of needs that drive our perception of reality and behaviors. These needs are complex and form our “value system”. He proposed that it is these value sets that form the basis of differing individual needs. The changes are hierarchical in nature (i.e., some needs to meet before other needs become important as a determinant of attitudes and behaviours). A need satisfied is no longer a dominant need; as a need is satisfied, new needs emerge. We all have these needs, but each one of us has one or two dominant ones. There is no “better” or “worse” need, there just ‘”is”.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is usually portrayed as a triangle with different needs from bottom to top, including Security, Belonging, Esteem and Self-Actualization. In an attempt to make it more accessible to business people, Maslow’s framework has been adapted to make it more amendable to be used as a tool to understand leaders’ and employees’ motive for action as seen in figure 5. The bull’s-eye represents needs as the target of our behaviour and attempts to overcome the misconception created by the triangle that needs at the top are somehow “better” than the needs at the bottom.

As represented in figure 5, all human beings are driven by the same fundamental needs as popularized by Maslow: Certainty; Connection & Love; Significance & Achievement; Variety/Novelty; Growth and Contribution (adapted from Maslow, 1970 and Robbins, 2008).

The figure represented is generic, but is most powerful when used as a tool to determine how these different needs are satisfied at work. Additionally, it is important to reflect about what is at the centre of your bull’s-eye that is driving you, and similarly, your clients, employees, and leaders[iii].

Maslow (1970) proposed three core motivational domains, which were: (i) Sustenance Driven needs: physiological, survival, security, and a sense of belonging; (ii) Outer-Directed needs: recognition, significance, and self-esteem; and (iii) Inner-Directed needs: self-actualization, personal growth, and transcendence.

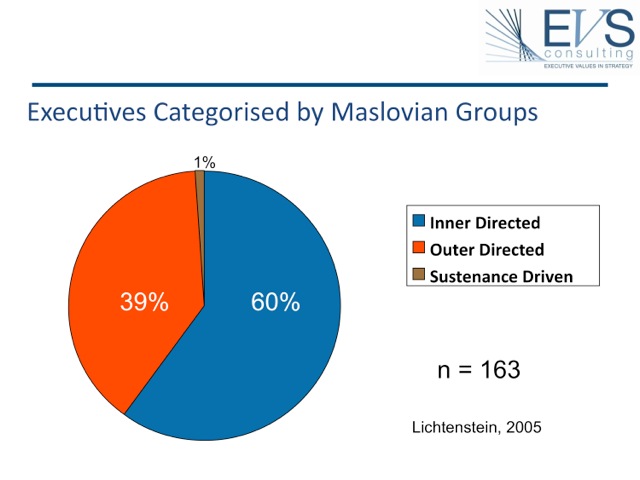

In the first operationalization of Maslow in a management context, over 50 years after it was first proposed, Lichtenstein (2005) tested Maslow’s assertion that executives’ personal value systems are related to Maslovian Sustenance Driven, Outer- and Inner Directed needs. In a study of 163 Owner-, Senior- and Middle managers, Kotey and Meredith’s (1997) List of Values (LoV) 28-item personal values scale was used to measure executives’ personal values. Drawing on Maslow’s (1970) theory of Inner Directed, Outer Directed, and Sustenance Driven value groups, a three-factor solution was extracted that revealed theoretically predicted results that were statistically reliable:

(i) the Sustenance Driven value system espoused the traditional values of Loyalty, Trust, Compassion, and Affection,

(ii) the Outer Directed value system espoused the core esteem-seeking values of Power, Prestige, Ambition, and Aggression, and

(iii) the Inner Directed value system espoused the entrepreneurial values of Innovation, Risk, and Creativity.

The results provided strong support for Maslow’s (1970) assertion that value systems correspond to the underlying needs that drive them, and for the three motivational domains or “worlds” of our leaders, employees, teams, companies, and societies.

Do you think your motivational domain would affect your leadership? The nature of the relationships you have? Your communication? What you wear? You bet. The consequences of our driving force and those of others are at the crux of leadership. Leadership and followership vary by one’s values.

Do you think your motivational domain would affect your leadership? The nature of the relationships you have? Your communication? What you wear? You bet. The consequences of our driving force and those of others are at the crux of leadership. Leadership and followership vary by one’s values.

How well do you understand the forces that drive employees and leaders to action? What percentage of each motivational group above would you except to find in an organisation or business function? Allocate to each group above, totaling 100 percent, your best guess concerning the top drives of an executive population. See figure 5 for the results, which have been replicated in two other studies of in-work managers with similar results.

2.2 The Values Dynamic

Do the numbers surprise you? Most executive groups are surprised by the small number of managers with Sustenance Driven needs and values and the large proportion of managers with Inner Directed needs and values. The results show a small percentage of managers categorised as Sustenance Driven, which supports published (e.g., Wilkinson & Howard, 1997) and unpublished reports (CDSM Ltd) on the decline of the working-age population in Western society who espouse traditional values.

This values dynamic shift, a decrease in the amount of managers with Sustenance Driven values, and an increase in the proportion of managers with Outer and Inner Directed values in our organisations, helps explain the nature of change in leadership and followership.

This values dynamic shift, a decrease in the amount of managers with Sustenance Driven values, and an increase in the proportion of managers with Outer and Inner Directed values in our organisations, helps explain the nature of change in leadership and followership.

Based on measurement and observation, the top levels of organisations are heavily over-represented by Inner Directed executives whose dominant need for novelty and values of Innovation, Risk, and Creativity is likely to be perceived as a threat by those with different values. The innovation-based “further and faster” orientation of the Inner Directed may be lauded at Board level, but perceived by the Outer Directed – who are the organisation’s operators – to be too radical and to frustrate their ability to hit their targets. The Sustenance Driven, who prize safety and continuity of traditional methods, may just consider the orientation of their leaders to be madness.

Dis-ease in the culture is caused by leaders who fail to understand that what is “the ideal solution” and “logical” in the Boardroom and executive suite is perceived as “too much too soon” or not being “a safe pair of hands” by those with other values. The nature of this opposition is often not open to rational discussion. Many people will not even know why they are opposing the offered solution/strategy they are tasked with implementing – it just feels wrong. This is an indication that the opposition is based in the value system rather than in a straightforward examination of the facts. Thus, even more rational analysis will not convince them that the decision is right.

3. What can leaders do?

Leaders need to understand how to use the insight concerning how their needs and values shape the creation of goals and strategies that motivate their staff and culture to create more shareholder value. They also need to accommodate their leadership style to lead a culture with directors, executives, and managers with needs and values other than their own, if they are to optimise value for shareholders, stakeholders, and society.

New methods to create shareholder value are unlikely to reach their full potential if Board members and leaders are creating dis-ease. To create more value, both at the level of the corporate and business strategies, leaders need to ask themselves a range of questions based on the insights discussed in this paper if they are to deliver superior performance.

- How do I determine the values, beliefs, and motivations of my Board?

- How can I improve my effectiveness by making sure I am appealing to those values at the basic level (i.e., gaining acceptance for policies at the level that feels right)?

- How can I determine the values, beliefs, and motivations of my main stakeholder groups (e.g., staff, suppliers, communities where we are located, customers, market analysts)?

- How can I alter my style but keep my policies, to ensure that I bring on board these other stakeholders, even when they have different values from the Board?

- How can I use this information and knowledge to develop better policies and strategies to increase shareholder value in the future?

The values of the top team can and do create “dis-ease” with employees with different values at an unconscious level, which gives rise to beliefs such as “too much too soon” or “they (leaders) have lost the plot” that can lead to active resistance to policies and strategies, and in some cases sabotage, thus stymying strategy implementation.

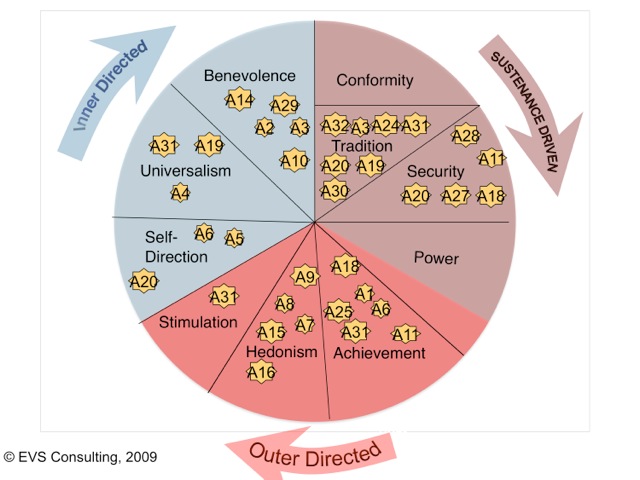

EVS Consulting (www.evsconsulting.co.uk) has developed a survey and reporting tool to help leaders gain insight to help answer these questions. The motivational map in figure 7 represents the values of a leadership team using a value system that has been tested for cross-culture reliability and validity, but is only just beginning to be used for business purposes. Going clockwise starting from 12 o’clock, the map below illustrates the Maslovian dynamic from the Sustenance Driven traditional value system of Conformity, Tradition, Security, and Power, to the Outer Directed value system of Achievement, Hedonism, and Stimulation, to the Inner Directed value system of Self Direction, Universalism, and Benevolence. Team members’ top two values are represented by stars with their unique letter and number.

The values dynamic of this team is hereby measured, which elucidates where they come together and pull apart.

One immediate observation is that the diversity of values in this team represents the diversity of values in organisational cultures. What makes this team particularly diverse is the unusually high proportion of managers with values in the Sustenance Driven motivational domain, as compared to the hundreds of other managers’ values we’ve measured. In the workshop when we presented our findings, the team couldn’t figure out why this was so, until it was pointed out to them that the Sustenance Driven managers came from India and Pakistan, as opposed to Europe, where the other members were from. Their knowing smiles immediately acknowledged the cultural dynamic affecting the team. This type of diversity is also found in cultures integrated by M&A.

With team members working in pairs, the results were used as a catalyst for a deep dialogue about the consequences of their needs and values for themselves and their leadership. This was authentic talk – a powerful antidote to the surface conversations they normally had. Participants were buzzing with excitement by the end of the session. They not only understood more about themselves, but also their colleagues. Implicitly, they developed empathy for colleagues who possessed different values from their own by understanding why they were different and appreciating their needs. Having a framework in which to understand needs and values, and data showing how these were distributed amongst the team, enabled them to connect to that part of themselves that others’ needs and values represented.

For leaders, this values mapping exercise provides data to benchmark and track the values dynamic underpinning their methods for creating value.

4. Conclusions

Values and motives for action are the crux of leadership and followership. Leaders need to understand how to use the insight of how their needs and values drive the creation of goals and strategies that motivate their staff and shape the culture to create more shareholder value. Leaders need to translate their missions, goals, and strategies into the operative values of their direct reports and employees to create tomorrow’s company today, as illustrated in figure 8.

Leaders also need to accommodate their leadership style to lead a culture with directors, executives, and managers who have needs and values different from their own, to optimise value for shareholders and stakeholders. New methods to create shareholder value are unlikely to reach their full potential if Board members and leaders are creating dis-ease.

What this paper hasn’t addressed, amongst other things, is how values may manifest themselves in predictable patterns of strategic decisions and behaviour, which may be the subject for a subsequent paper. New focus group research findings are emerging regarding how the leadership style, seen through the eyes of followers, varies between Inner and Outer Directed managers, challenging historic assumptions that leadership is solely about the characteristics of the leader.

We call on leaders to create more shareholder and stakeholder value by determining sustainable visions for their organisations and by translating those visions, goals, and strategies into the operative values of their employees. By understanding the invisible forces of values, leaders can implement value creation strategies further and faster throughout their organisations, harnessing and unleashing the strongest force in business today: the motivational driving force within each and every employee.

References

Allport, G W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Baker, S. (1996). “Placing Values Research in a Theoretical Context”, in Elfring, T., Siggard Jensen, H. and Money, A., (Eds.), Theory Building in the Business Sciences, Copenhagen: Handelshoyskolens Forlag

Beck, D.E. and Cowan, C.C. (1996). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change; Exploring the New Science of Memetics, Cambridge: Blackwell.

Bilsky, W. & Schwartz, E.S.H. (1994).Values and Personality, European Journal of Personality, 8, 2. 163-181

Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great. New York: HarperCollins.

Dade, P. (2008). Managing Talented People – Managing Resource: Managing a process of resourcefulness? http://www.cultdyn.co.uk/ART067736u/Managing%20Talented%20People.pdf

Finkelstein, S. and Hambrick, D. (1996). Strategic Leadership: Top Executives and Their Effects on Organisations, St. Paul, Minn.: West Publishing Company

Hambrick, D C & Brandon, G L (1988). “Executive Values” in Hambrick, D C (Ed), The Executive Effect: Concepts and Methods for Studying Top Managers Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 5 – 32.

Hambrick, D.C. & Mason, P.A. (1984). “Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of its Top Managers”. Academy of Management Review, 9, 193-206

Hindo, B. (2007). At 3M, A Struggle between Efficiency and Creativity: How CEO George Buckley is managing the yin and yang of discipline and imagination. BusinessWeek, Inside Innovation, June 11.

Higgs, M.J., & Lichtenstein, S. (2010). Exploring the “Jingle Fallacy”: A study of personality and values. Journal of General Management

Kelley, E.L. (1927). Interpretation of Educational Measurements. Yonkers, NY: World

Kotey, B & Meredith G G. (1997). Relationships among Owner/Manager Personal Values, Business Strategies and Enterprise Performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 35, 2, 37-64.

Lichtenstein, S. (2005). Strategy Co-Alignment: Strategic, Executive Values and Organizational Goal Orientation and Their Impact on Performance. DBA Thesis, Brunel University.

Lichtenstein, S., and Dade, P. (2007). “The Shareholder Value Chain: Values, Vision and Shareholder Value”. Journal of General Management. Vol. 33, Issue 1, Autumn, pp. 15-31.

Maslow, A H. (1943). A theory of human motivation, Psychological Review, 50, 370-96.

Maslow, A H. (1970). Motivation and Personality (2nd edition) Harper & Row, New York.

McCrae, R. R. & P. T. Costa. (1997). “Personality Trait Structure as a Human Universal”, American Psychologist 52, 5, 509-516.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy, New York: The Free Press.

Robbins, A. (2008). Creating Lasting Change. Anthony Robbins Companies.

Rokeach, M. (1979). From individual to institutional values with special reference to the values of science. In Rokeach, M (Ed) Understanding Human Values; 47-70, New York: Free Press.

Roland, D. and Higgs, M. (2008). Sustaining Change: Leadership that Works. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Schwartz, S. (1996). “Value Priorities and Behavior: Applying a Theory of Integrated Value Systems” in C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The Psychology of Values: The Ontario Symposium, Volume 8, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Tay, L. and Diener, E. (2011). Needs and Subjective Well-Being Around the World. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2011, 101, 2, 354–365

Taylor, B. (2010). Conversation with.

Waters, M. (2008). Leadership values. MBA Dissertation, Henley Management College/Brunel University.

Wikipedia:

Hewlett-Packard, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hewlett-Packard

James McNerney, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_McNerney

George Buckley, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_W._Buckley

Wilkinson, H. and Howard, M., (1997), Tomorrow’s Women, London: Demos.

Endnotes

[i] Reality 2.0 is an allusion to Web 2.0, a new version of the World Wide Web that allows users to interact and collaborate with each other in contrast to Web 1.0 where users are limited to the passive viewing of content that is created for them.

[ii] The HP Way was defined by co-founder Bill Hewlett as “a core ideology … which includes a deep respect for the individual, a dedication to affordable quality and reliability, a commitment to community responsibility, and a view that the company exists to make technical contributions for the advancement and welfare of humanity.” (Wikipedia) The following are the tenets of The HP Way:

We have trust and respect for individuals.

We focus on a high level of achievement and contribution.

We conduct our business with uncompromising integrity.

We achieve our common objectives through teamwork.

We encourage flexibility and innovation.

[iii] Exercises based on this model can be found in Lichtenstein, Higgs, and Martin-Fagg’s (2009) From Recession to Recovery: A Leadership guide for Good and Bad Times, Osney Media.: http://www.troubador.co.uk/book_info.asp?bookid=920

About the Author

Dr. Scott Lichtenstein is a founding Director of EVS Consulting, Visiting Faculty at Henley Business School and will be Senior Lecturer in Strategy at Birmingham City University from January 2012. Scott lectures, researches and publishes in the areas of Strategic Leadership and Corporate Governance as well as coaches. He specialises in leaders’ and executives’ personal values and their impact on strategic choice and organisational performance. His consulting is mainly focused around a leadership values instrument and reporting tool he has developed.

Scott has worked at Henley Management College and Warwick Business School. Prior to that he was a consultant with a market research-based brand strategy consultancy and worked in Belgium as a consultant for Hill & Knowlton International Brussels, a Public Relation/Public Affairs company, and in the European Commission’s Enterprise Policy directorate.

Scott was born and raised in Oakland, California. Along with his DBA and MBA from Henley Management College, he has a BA in Political Science with an International Relations emphasis from the University of California at Santa Cruz. He has completed certificate courses in facilitation and coaching.