Nick Obolensky. Complex Adaptive Leadership. Farnham, Surrey, England: Gower, 2010

Nick Obolensky. Complex Adaptive Leadership. Farnham, Surrey, England: Gower, 2010

Nick Shannon

In one of the appendices to this book, the author tells a story about Cheyenne Indian tribes whose initiation rights for young men included sending them out on a hunt for buffalos. Invariably such hunts were initially unsuccessful. Returning empty handed, initiates would be sent to the medicine man who would bolster their courage and confidence by providing a “magic” buffalo map, written on a piece of hide, that showed the likely location of a herd. With the map in hand, the young men would sally forth once more, this time returning with more success by finding and killing a buffalo. However, when the medicine man tried to retrieve his map, far from attributing their success to it, the initiates criticised it for its many inaccuracies. The buffalo were found in a far different place to that indicated by the map. And so, in telling a story against himself, Obolensky neatly deflects critics who might want to say: “that’s not what leadership is about”.

Putting aside all consideration for the moment of what “complex adaptive leadership” is or isn’t, this book is actually a startlingly worthwhile read for a business manager keen to develop a practical understanding of different strategies with which to engage subordinates. It is very clearly laid out, contains useful summaries at the end of every chapter and section, and includes exercises to stimulate thinking and embed concepts. Despite the implication of the book’s title, the message of the book is well argued and simple to grasp.

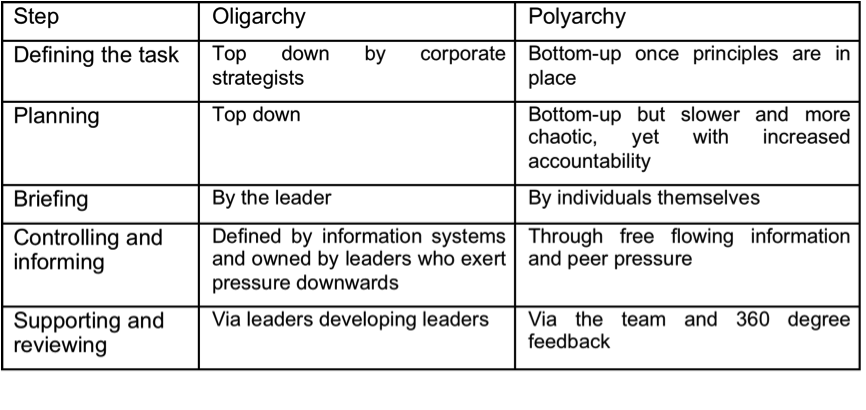

The book is laid out in four parts. In part 1, Obolensky introduces the concept of “Polyarchy” as contrasted with oligarchy. “Polyarchy sees leadership as a complex dynamic system rather than just an attribute or something only assigned leaders do, and is based on the dynamics and features underscoring complexity science and chaos mathematics”. Polyarchy arises out of an integration of the concepts of anarchy and oligarchy, hence a polyarchic leader can practice “Wu Wei”, the Taoist art of inaction. Perhaps surprisingly, Taoism is a recurrent theme throughout this book, since Obolensky seeks to instil in his readers an appreciation of ambiguity and paradox. Taoism, he explains, embraces three principles, that of a natural flow to what happens in the universe, that of simplicity contained within complexity (hence the conclusion that the more complex a situation, the less leadership action is needed), and that of opposites combining as with Yin and Yang.

Obolensky’s theme is that once certain core principles are understood and in place, then the job of leadership is far more fluid and adaptive than might be recognised by traditional leadership models. He argues that the context of leadership has changed much faster than our conception of, and assumptions about, what leadership actually is. For example, organisations are moving from being organised in functional “silos” to being organised as cross-functional matrices, and now are moving towards becoming complex adaptive systems where traditional lines of hierarchy are replaced by fluid work teams that “bubble-up”, perform, and disappear. Examples cited include the Danish hearing aid manufacturer Oticon (management style known as spaghetti organisation), Semco in Brazil, Johnsonville foods in the U.S., and St Luke’s in the U.K. In such organisations, those at the top can no longer pretend to know that they have the answers, and those at the bottom who have the answers can no longer pretend that they don’t. Hence, oligarchy (rule from the top) is replaced with polyarchy where authority is given dynamically to those best placed to exercise it.

In Part 2, Obolensky sets out to derive a set of principles that can underpin the application of polyarchic models of leadership. He draws principally from science by citing findings from the fields of relativity, quantum mechanics, chaos and complexity. Such findings provide a way to think about leadership in organisations. Einsteinian and Newtonian physics show us that contradictory rules can meaningfully co-exist. Quantum mechanics point us to the non-deterministic nature of underlying reality. Chaos mathematics demonstrates how chaos also has order and patterns (in the form of strange attractors), whilst complexity science shows us how complex forms can have an inherent simplicity (fractal patterns), can be self-organising, adaptive, and emergent.

If you go to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=41QKeKQ2O3E you can see Obolensky demonstrate self-organisation in a class of about 20 management trainees. With the class scattered standing around a large room he asks them to position themselves equidistant from two others in the group without identifying which two people they have picked as a reference point. Shuffling to and fro, the group achieves the objective. Following Obolensky’s clearly laid out rules, they achieve this within a minute. Obolensky congratulates them and then, to much laughter, asks “What would have happened if we had put one of you in charge?”

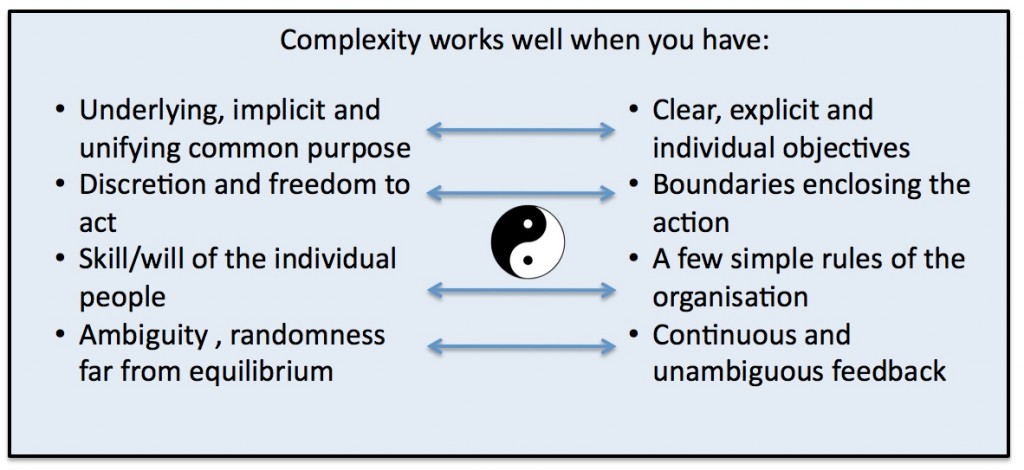

In chapter 7, “Getting Chaos and Complexity to work” Obolensky draws eight principles that he considers are necessary for groups to complete highly complex tasks. These are called the “Four + Four principles” and are linked to the success factors identified in the books “Built to Last” and “Good to Great” by Jim Collins. Polyarchy is best enabled when these principles are applied.

These principles are intended to be inter-dependent and dynamic, although they may also be somewhat in tension. They combine what might be considered a soft “theory Y” view of people with a harder “theory X” perspective (to speak with Herzberg). The difficulty, one might assume, is in getting the balance right and communicating the concept to employees. The yin/yang symbol in the centre of the diagram is intended to emphasise the opposite nature of each pair of principles, each containing a small element of each other and yet co-existing and together containing the potential for something greater than the sum of their parts.

Obolensky gives a number of “best practice” examples where he has observed such principles in action. The Walt Disney company is cited as an example of having a clear and meaningful purpose (“To make people happy”), whereas the UK retailer Marks and Spencer’s purpose declared by a one time CEO to “ensure shareholder value” is not. Similarly, objectives need to be specific and set in the context of what needs to be changed and how.

What does Obolensky mean by the principle of Skill/Will? Here, he draws attention to the difficulty of managing the ability and motivation of people to do their jobs. However, he says little about the question of what constitutes ability/skill or how it relates to will/motivation. Instead, he focuses on motivation and the dangers of leaders demotivating followers by using inappropriate oligarchic behaviours. He sees motivation as a matter of “state” rather than “trait” and suggests that the appropriate leadership tactics can influence peoples’ motivation. This is a contentious suggestion and yet many managers may find useful Obolensky’s description of four motivational states and the need for leaders to apply a mix of challenge and support appropriate to the state in which a person is found. The four states themselves each constitute a combination of two contradictions:

Performance – A combination of high levels of engagement whilst being relaxed

Parking – A combination of being relaxed and bored (low engagement)

Stress – A combination of engagement and anxiety

Depression – A combination of disengagement and anxiety

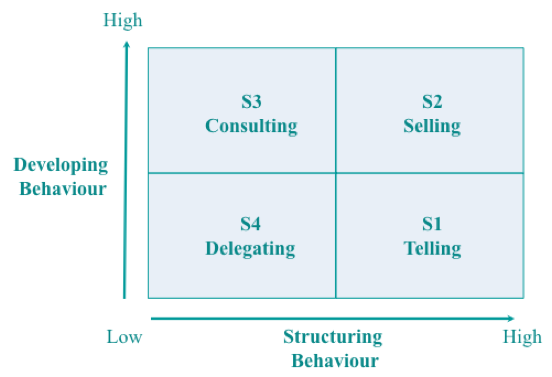

Having established the context and derived his strategic principles, in part 3 Obolensky tackles tactics. First, he succeeds in breathing new life into an old model, Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership grid. The grid, developed in the 1960’s, is still staple fodder for innumerable middle management training courses throughout the UK.

The model depicts four leadership styles differentiated by focus on the task (horizontal axis) and focus on the person (vertical axis). Obolensky identifies four archetypal leaders whose style is predominantly one of those 4 variants:

S1. The “Heroic/Strong” leader uses a style that is high on structure and low on development. The leader knows what to do, tells people and ensures that they do it.

S2. The “Inspirational/Transformational” leader uses a style that is high on structure and also high on development. The leader knows what to do but needs followers to “buy into” the solution and hence “sells” a vision.

S3. The “Participative/Facilitative” leader uses a style that is low on structure and high on development. The leader allows followers to decide what to do but supports them in doing it.

S4. The “Empowering/Hands-off leader” uses a style that assumes followers know how to do the task and will get on with it. The approach is low on structure and development.

The book contains a self-assessment questionnaire with which readers can identify their own preferences on this model. Typically, scores for a management population show a strong bias in favour of S2 and S3, the selling and consulting styles, with S1, telling next strongest, and S4, delegating the lowest. Obolensky’s research data suggests only 8% choose the delegating style (by comparison with this reviewer’s data of less than 5%) indicative of three key challenges facing today’s executives:

- The need to let go

- The sense of working too hard

- The acting out of a charade of pretending they have the answers when they and their followers know that they don’t.

The solution to get out of these traps is offered in Chapter 10. Leaders must nudge their followers towards being both competent and motivated. Overlaying followers “skill” and “will” onto the leadership style matrix yields potential tactics for each combination:

S1, Tell – for followers with low skill and high will

S2, Sell – for followers with low skill and low will

S3, Involve – for followers with high skill and low will

S4, Delegate – for followers with high skill and high will

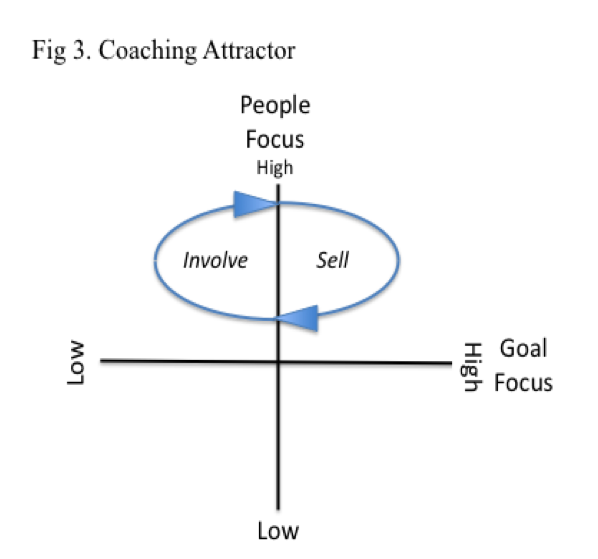

Here Obolensky moves beyond Hersey and Blanchard’s simple conception of selecting an optimum style and applies chaos theory’s concept of attractors to define patterns of movement between combinations of styles. For example, a leader using a “coaching attractor” would cycle repetitively between S2 (selling) and S3 (Involving) styles. Coaching questions taken from the “GROW” model described by Sir John Whitmore could be applied selectively at the “sell” stage to focus the person being “led” on what would motivate them (what is the Goal and how do they feel about achieving it?) and again at the “involve” stage to generate ideas on how to proceed (what is the situation and what options are there to deal with it?).

Competent leaders, therefore, are able to use a variety of attractor patterns selectively and dynamically using their analysis of the demands of the situation and the nature of their followers. The sophistication of their analysis of either of these elements may vary, but the principles remain the same and involve combining a focus on people with a focus on the goal or task in different ways. The ultimate aim is to enable the “devolved” style as much as possible, where to quote Lau Tzu “the people will say, we did it ourselves”.

Part 4 of the book is given over to a brief motivational chapter for leaders and four appendices. In the chapter 11 Obolensky asks the reader to reflect on four “KISS” questions. What – in relation to the lessons of the book – is the reader already doing well and should Keep doing? What can the reader do well, but should Increase? What should the reader now Start doing? And lastly, what is the leader doing that is not actually needed, and should Stop? This piece concludes the book as a textbook for aspiring leaders.

More interesting themes are pursued in the second and third appendices. The first demonstrates Obolensky’s ability to integrate different models of leadership as he aligns the eight principles of the “Four + Four” model with John Adair’s “Task/Team/Individual” and “Seven Functions” models of leadership. Essentially, this leads to a distinction between oligarchy, where the leader is focused on doing the functions and providing the content, and polyarchy where the team perform the functions and the leader is focused on ensuring the process. The process advocated here involves five step one as follows:

Appendix C explores the relevance of the themes in the book to political leadership. This is perhaps the most interesting part of the book in that Obolensky argues that democracy has taken a step backwards. If today’s society calls out for polyarchy, the response from those in power has been to extend their powers.

In the UK political systems should be enabling wider participation and debate but the opposite is happening as evidenced by lower levels of voting, less toleration of opposition through the control of freedom of expression, more centralised control via widespread CCTV surveillance, and more draconian police/legal powers. This argument is only partially effective since, amongst other things, voter turnout in the UK general elections was stable between 70% and 80% from 1950 through to 1997 only registering a sharp fall in 2001 to 60%, and since recovering to 65% in 2010.

But be that as it may Obolensky may be right to point out, given the current economic malaise of Europe, that rule by a political elite is not as effective as it needs to be. There are unexploited opportunities to involve citizens more actively in the governance of their country (largely presented by the sort of technology and process currently being promoted by John Bunzl’s Simpol). He neatly gives examples of how the Four + Four principles might be applied in bringing about a change in political involvement of the people – for example one simple rule might be that of making failure to vote illegal, as in Australia. The principle of people’s skill and will is less obviously applied. People need to be capable of joining political debates and motivated to do so. The point is well made regarding the importance of this principle, but how to engender it? Ironically, it seems that it only promotes greater dissatisfaction with the status quo that creates such revolution.

At first sight, Complex Adaptive Leadership might seem like old wine in a new bottle. Obolensky has trawled through contemporary business leadership models and played around with them using some thinking taken from modern physics. The Four + Four principles will also be familiar to anyone with a passing interest in periodicals such as the Harvard Business Review. Yet, there are signs of some strong dialectical thinking here and the result is a clever integration of ideas about leadership as well as a practical guide that leaders and would-be leaders will find readable. The sub-title “Embracing Paradox and Uncertainty” gives a steer on what Obolensky is seeking to express. His claim is not that there is one “best way” or a single best model for leadership. Instead, he sees it in terms of process set inside a larger context. The process is dynamic and emergent, and hence adaptive. Leaders best chance of navigating complexity is through the application of simple principles and the acceptance that no “oligarch” can be expected to have answers to all the challenges facing a modern organisation. Instead the “wisdom of crowds” must be invoked.

From an integral “AQAL” perspective, Obolensky largely ignores the upper left quadrant – the subjective experience of leadership and followership. He does not pretend to take a psychological approach. The implication of this omission is that any selection of leadership tactics following the application of the Hersey and Blanchard model might succeed or fail depending on the perception of the leader’s actions by followers. And he also pays little heed to levels of development, perhaps regarding his principles and models as applicable at any level as evidenced by his discussion of political leadership. Without a theory of work or some discussion of the Jaquesian idea that leadership is requisite depending on the relative developmental positioning of followers vis à vis their leader, readers might find themselves misled into thinking that leadership is largely a matter of selecting the appropriate behaviours.

This book will be of most use to managers making the transition from middle to more senior management levels, as well as to leadership coaches needing to answer some questions about the validity of 20th century leadership models in the 21st century. As a dialectical thinker, Obolensky makes much of the ancient text of the Tao Te Ching to invoke the sense that leadership is as much about not doing as it is about doing. The assumption here is that empowerment and self-organisation can allow leaders the opportunity to “let go”. Whilst many of today’s leaders might wish that this were true, not all of them will feel they can afford the luxury of fading into the background in a corporate world where the ambiguity of responsibility for results means that people are judged more by action than inaction.

As a management guide, Nick Obolensky has written an entertaining, highly readable, well set out and informative book. For this reviewer, the buffalo may still be far over the horizon, but at least he had fun trying to find them with the map.

About the Author

Nick Shannon is the Associate Editor and Bureau Chief and guest editor of this, the January 2012 issue of Integral Leadership Review. He is the founder and principal of Management Psychology Limited, a UK-based practice specialising in organisational and senior management development. Nick is a chartered occupational psychologist, a member of the British Psychological Society and a founding member of the Association of Business Psychologists.

While Nick consults extensively in the UK, he has also consulted in Europe and the USA. Email: n.shannon@mpsy.co.uk