Marie Legault

Abstract

This article focuses on the development of conscious and world-centric leaders and businesses and, ultimately, conscious capitalism. In order for leaders to transform society and organizational cultures, they must first develop their own capabilities. The global context of business now requires leaders to think, feel, and act at world-centric stages of development in order to deal with the complexity of the global economic environment and create opportunities for a sustainable future. Research suggests that only a minority of our organizational leaders has evolved to a world-centric perspective. This raises a critical question: How can leaders develop themselves and their organizations toward a world-centric perspective? This article seeks to address this question and provides recommendations.

Corporations are probably the most influential institutions in the world today, yet people do not believe that they can be trusted, seeing them as only interested in maximizing profits. The recent protests on Wall Street and in cities around the world attest to this. In fact, investors are losing confidence in the ethics and values of executives, CEOs, and boards of directors. Study results from the Gallup Organization suggest that only 15% of the American public believe that business executives are honest and ethical (Gallup Organization). It is reported that organizations lose an estimated 5% of annual revenues to fraud, which translates into a potential global fraud loss of more than $2.9 trillion per year (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners “2010 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse”). In addition, occupational frauds, the most costly form of fraud, are most often committed by executives and upper management. Regulations, guidelines, and corporate governance practices have been put in place to restore corporate credibility and public confidence in capital markets (Brooks and Selley). Yet corporate misconduct has often occurred within the system implemented to prevent such misconduct (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners “2008 Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud & Abuse”; Waldman and Siegel). Ethical behavior is now recognized as indispensable for long-term corporate success and effectiveness and a sustainable global economy. In fact, global CEOs identify integrity as the second most important leadership quality in the new economic environment (IBM).

New Kind of Leadership

The leadership literature offers several definitions of leadership (Rost), although Ciulla argues that leadership definitions are often “theories about how people lead (or how people should lead) and the relationship of leaders and those who are led” (Ciulla 11). A search for the answer to the question “What is leadership?” led Hunt to conclude that one’s perspective on leadership depends on one’s ontological assumptions (how one chooses to define the phenomenon) and epistemological assumptions (how one forms knowledge about the phenomenon) about the definition and purpose of leadership (J. Hunt, G.).

Most leadership theories provide an outer perspective or focus on a leader’s visible actions and behaviors. A limited number of theories feature an inner perspective or focus on a leader’s development. Few theories make the link between the inner and outer perspectives, and fewer still consider the impact of a leader’s environment on his or her development and behaviors. The development and focus of leadership theory and research has reached the point where it needs to integrate all of the elements that constitute leadership, including “the relevant actors, context (immediate, direct, indirect, etc.), time, history, and how all these interact with each other to create what is eventually labeled leadership” (Avolio 25).

Growing global competitive pressures, uncertain economic times, a questionable ethical climate, and growing environmental issues are challenging leaders at all levels and in all types of organizations. The problems facing organizations today call for a new kind of leadership. Recent leadership literature proposes new leadership approaches to better meet today’s global challenges. Here follows a discussion of five of the emergent leadership approaches: advanced leadership, leadership agility, integral leadership, conscious leadership, and ethicful leadership.

Advanced leadership suggests that advanced leaders work in complex systems and are aware of and recognize the multiple stakeholders and their divergent interests and needs. Advanced leaders break mental boundaries and challenge established patterns to effect real change (Moss-Kanter). Leadership agility focuses on a leader’s ability to lead effectively under conditions of rapid change, higher levels of complexity, and growing interdependence. Agile leaders are skilled in four mutually reinforcing leadership agility competencies – context-setting agility, stakeholder agility, creative agility, and self-leadership agility (Joiner and Josephs). Integral leadership is an approach that offers a comprehensive framework for taking into account recognized dimensions of the individual and the organization. Integral leaders have the ability to look at complex situations through the various “AQAL lenses” in order to better view and effectively deal with the situation and its challenges (Thomas and Volckmann; Thomas). Conscious leadership is essential to creating conscious businesses. Conscious leaders are driven primarily by a desire to serve the organization’s purpose while simultaneously delivering value to all stakeholders. They view their organizations as part of a complex, interdependent, and evolving system with multiple stakeholders (Sisodia, Wolfe and Seth; Strong). Ethicful leadership suggests that a leader’s ethical life is an expression of his or her overall development as a human being, and attaining the full ethical potential of one’s life involves living in harmony with the universe as a whole. Ethicful leaders are individuals who have raised their consciousness and integrate inner and outer worlds in all that they do– including establishing ethical cultures – to contribute to the better good of others or all living things (Legault).

Although these theories and approaches explore leadership in its various dimensions, what they have in common is leaders with the capacity to take on different and expanded perspectives. We need leaders who have expanded their perspectives to a world-centric view and who purposefully create value in order to face the uncertainty of our changing world and address global challenges.

Conscious Capitalism

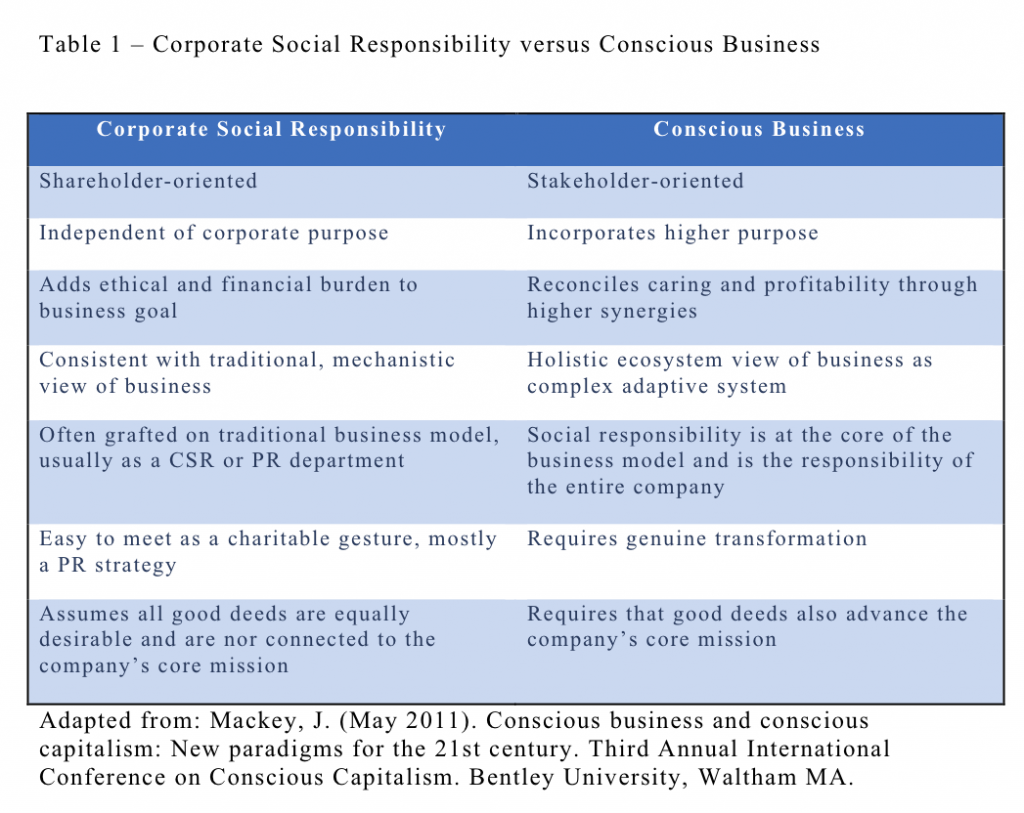

Conscious capitalism is an emerging philosophy based on the belief that businesses can enhance corporate performance while simultaneously improving the quality of life for all stakeholders. Conscious capitalism goes beyond corporate social responsibility by placing societal needs and their challenges at the core of the company’s existence (Porter and Kramer). Efforts are driven naturally and internally rather than being reactive, externally prompted attempts to be socially responsible, which may have little to do with the core functions and culture of the organization. Table 1 compares corporate social responsibility principles to conscious business principles. Conscious capitalism transforms the existing notion about capitalism by changing the either/or paradigm to a both/and mentality by simultaneously creating financial and societal wealth. A study found that investments in companies that adhere to conscious business principles outperformed the market by a 9-to-1 ratio over a ten-year period. These companies also outperformed the companies described in the book Good to Great (Collins) by a 3-to-1 ratio over a ten-year period. Beyond financial wealth, these companies also create many other kinds of societal wealth, such as more fulfilled employees, happy and loyal customers, innovative and profitable suppliers, and thriving and environmentally healthy communities (Sisodia, Wolfe and Seth). Conscious capitalism results when conscious leaders create conscious businesses. Let us explore these two determinants of conscious capitalism.

Conscious capitalism transforms the existing notion about capitalism by changing the either/or paradigm to a both/and mentality by simultaneously creating financial and societal wealth. A study found that investments in companies that adhere to conscious business principles outperformed the market by a 9-to-1 ratio over a ten-year period. These companies also outperformed the companies described in the book Good to Great (Collins) by a 3-to-1 ratio over a ten-year period. Beyond financial wealth, these companies also create many other kinds of societal wealth, such as more fulfilled employees, happy and loyal customers, innovative and profitable suppliers, and thriving and environmentally healthy communities (Sisodia, Wolfe and Seth). Conscious capitalism results when conscious leaders create conscious businesses. Let us explore these two determinants of conscious capitalism.

Conscious Business

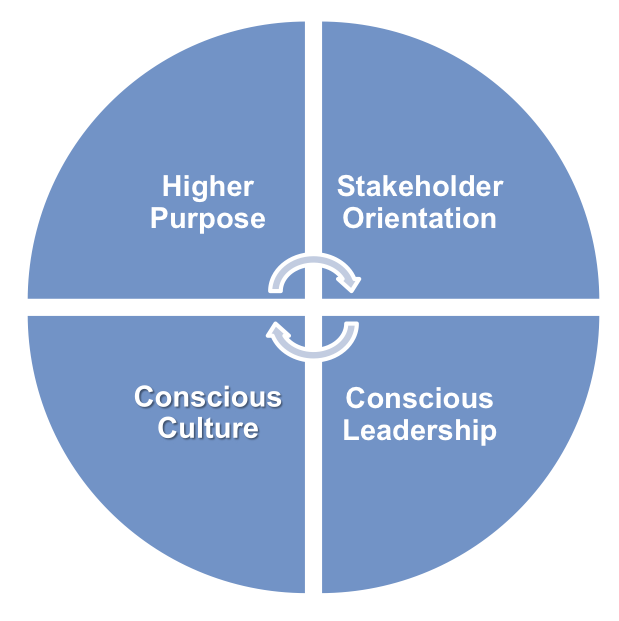

Conscious business is driven by the company’s “raison d’être” or higher purpose. Higher purpose, one of the four characteristics of conscious business, transcends profit maximization and engages all stakeholders – customers, employees, investors, suppliers, and the larger communities – in which the business participates. Whole Foods Market’s higher purpose is described as “whole foods, whole people, whole planet.” The term “whole foods” guides the company to offer the highest quality, least processed, most flavorful, and natural foods; “whole people” represents employees who are passionate about healthy foods and a healthy planet; and “whole planet” is the company’s commitment to helping take care of the communities and the planet.

Conscious business is also driven to create value, in various and often different ways, for all stakeholders. A stakeholder orientation, another characteristic of conscious business, suggests that businesses are part of a complex, interdependent, and evolving system. Efforts are focused on generating synergistic win-win situations that advance the whole system. Desso, a Netherlands-based manufacturer of commercial and domestic carpets and artificial grass for sports, is a good example of an organization that embraces the stakeholder orientation. Desso has moved away from the cradle-to-grave practices and adopted the cradle-to-cradle approach. The cradle-to-cradle approach goes beyond sustainability because it focuses on full-circle processes that seek to enrich the earth and benefit all stakeholders. These creative and cost-effective ecologically innovative business efforts create profitable and ethical manufacturing processes and corporate practices (McDonough and Braungart).

Another characteristic of a conscious business is its culture, which can be felt yet is difficult to describe. The Conscious Capitalism organization suggests that the acronym TACTILE best captures a conscious culture (Conscious Capitalism). TACTILE integrates elements of trust, authenticity, caring, transparency, integrity, learning, and empowerment. Southwest Airline and The Container Store are examples of organizations that incorporate the elements of a conscious culture.

Conscious Leadership

Conscious leadership is also a characteristic of conscious business and foundational to conscious capitalism. Because the public neither believes nor trusts organizations and their leaders, one can wonder – who are these conscious leaders who work from a place of higher purpose, take on an expanded view to deliver value for all stakeholders, and create conscious cultures? To answer this question, we turn to adult and leader development theories.

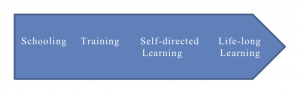

There are two dimensional aspects to development: horizontal and vertical growth (Cook-Greuter “Making the Case for a Developmental Perspective”). Horizontal growth occurs through exposure to life and its many learning processes, such as schooling, training, and self-directed and life-long learning. Horizontal development is the most common dimension since most of the learning, training, and development practices in organizations and society are focused on expanding, deepening, and enriching one’s current way of making sense of the world. Vertical growth, on the other hand, does not occur as often, and is more powerful than horizontal growth because it transforms a person’s way of making sense toward taking a broader perspective and, as such, develops new ways for adults to think, feel, and act.

There is evidence that the developmental process that transforms one’s sense-making toward taking a broader perspective occurs in successive stages or levels, each of which integrates learning from the prior stages into a more complex structure (Richards and Commons; Cook-Greuter “Making the Case for a Developmental Perspective”; Rooke and Torbert; Kegan; Fisher, Kenny and Pipp; Cook-Greuter “Postautonomous Ego Development: A Study of Its Nature and Measurement”). The stages form a tiered system. At the first tier, leaders at the pre-conventional level are guided by their needs, which results in ego-centric behavior. At the second tier, conventional leaders take on a socio-centric or ethno-centric view, where concern for others is limited to their immediate circle – their work group, family, company, or nation. At the last tier, post-conventional leaders take a world-centric view that encompasses the entire planet.

Leaders who have reached a world-centric perspective create value for all stakeholders because they recognize that the needs of society and corporate performance intersect. They believe that doing well and doing good are linked (Strong; Sisodia, Wolfe and Seth; Mackey; Swartz). In fact, organizations led by leaders who simultaneously align the interests of all stakeholders – society, partners, investors, customers, employees, and the environment – outperform well-known organizations recognized for their financial success (Mackey; Sisodia, Wolfe and Seth).

Findings from a recent study suggest that leaders with a world-centric view are ethicful and conscious about the way they think, feel, and act. The study highlights how world-centric leaders have a desire to be of service and experience ethics as heartfelt. Such individuals have a heightened self-awareness and a broader perspective, an innate desire for and commitment to continuous development, and a spiritual core. In addition, world-centric leaders look for organizations that are congruent with their guiding values and seek formal and informal support and trusting relationships to enhance their development (Legault).

A supportive ethical, conscious organizational culture influences the development of ethical, conscious leaders and helps broaden its leaders’ perspectives to a world-centric view (Legault). Much like the process in individuals, the ethical development of organizations appears to take place from a corporate-centric perspective (the ego-centric level or pre-conventional tier), to a community-centric perspective (the ethno-centric level or conventional tier), to a world-centric perspective (the post-conventional tier) (Wilber and Walsh). However, the successful creation of a culture that develops and sustains ethical, conscious leaders and leaders with a world-centric view depends on the integrity and moral character of its leaders and organizational members (McGuire and Rhodes).

Our socio-cultural context requires leaders to think, feel, and act with a world-centric view in order to address the complexity of the global economic environment and create opportunities for a sustainable future. According to the developmental psychologists Robert Kegan and Susanne Cook-Greuter, there is a genuine concern that leaders are in over their heads or up to their chin when coping with the narrow rationalistic Western mindset. Research indicates that approximately 20% of adults in developed countries reach the capacity to think, feel, and act with a world-centric view (Cook-Greuter “Postautonomous Ego Development: A Study of Its Nature and Measurement”; Kegan; Rooke and Torbert). Given this statistic, a minority of our organizational leaders has evolved to a world-centric perspective. This raises a critical question and challenge: What can be done to accelerate the development of ethical, conscious leaders and conscious businesses in order to create a sustainable future for the next generations? To help meet this challenge here follows a few recommendations that emerged from interviews conducted with leaders who have reached world-centric perspectives (Legault).

Recommendations

Since leader development is mostly experientially driven (Day, Harrison and Halpin), organizations can accelerate the development of ethical, conscious leaders by designing experiential learning activities and action learning programs. Action learning and action inquiry are processes and programs that have the capacity to effect individual and organizational changes simultaneously (Marquardt; Torbert et al.). Leaders that expand their levels of consciousness and develop greater psychological complexity through differentiation and integration create ethical, conscious cultures (Logsdon and Young; McGuire and Rhodes). In order to expand leaders’ perspectives and transform organizational cultures, action learning and action inquiry initiatives need to incorporate: horizontal and vertical development; the four elements of conscious business – higher purpose, stakeholder orientation, conscious leadership, and conscious culture –; and learning at the personal leadership level, organizational leadership level, and systems leadership level.

There is growing evidence that narratives are at the heart of leadership. Telling a story is a leadership behavior that provides leaders with a self-concept from which they can lead (Shamir, Dayan-Horesh and Adler). Story-telling or the construction of a life story is a major element in the development of authentic leaders (Shamir and Eilam). In addition, authenticity in leadership is emergent from a narrative process in which others play a constructive role in the self (Sparrowe). Dialogue initiatives can accelerate the development of ethical, conscious leaders by providing leaders with an opportunity to narrate their experiences and learn from each other. The process engages leaders to broaden their perspectives by offering a path for understanding and effectiveness that goes to the heart of what it is to be human – the meaning-making, thinking, and feeling that underlies actions (Isaacs). Dialogue initiatives create learning environments that can empower employees and encourage integrity, authenticity, and transparency within the organization (Senge; Senge et al.). Dialogue can also establish trusting and caring relationships among employees and, in turn, improve the organizational culture.

Having the support of a professional leadership coach is another way to accelerate the development of ethical, conscious leaders. Research suggests that ethical, conscious leaders seek support from leadership coaches for their professional development (Legault). Leadership coaching – a just-in-time, one-on-one development process – can help leaders develop on both the horizontal and vertical growth and, as such, help leaders expand their capacity to incorporate broader perspectives (J. Hunt). Team coaching can increase the team effectiveness and, in turn, effect the organizational culture (Anderson, Anderson and Mayo).

Conclusion

The need for developing ethical, conscious leaders has never been greater if organizations are to deal with the complexity of the global economic environment and create opportunities for a sustainable future. Developing leaders with a world-centric perspective is essential in order to create and sustain conscious businesses – businesses that are guided by a higher purpose, that seek to deliver value for all stakeholders simultaneously, and that build conscious cultures. Conscious leaders that lead conscious businesses are conscious capitalists. They can advance the development of a conscious society. The starting point is the development of leaders with a world-centric view.

References

Anderson, Merrill C., Dianna L. Anderson, and William D. Mayo. “Team Coaching Helps a Leadership Team Drive Cultural Change at Caterpillar.” Global Business and Organizational Excellence 27.4 (2008): 40-50. Print.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. “2008 Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud & Abuse”. Austin, 2008. . <http://www.acfe.com/resources/publications.asp?copy=rttn>.

—. “2010 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse”. Austin, 2010. September 10 2011. <http://www.acfe.com/rttn.aspx>.

Avolio, Bruce J. “Promoting More Integrative Strategies for Leadership Theory-Building.” American Psychologist 62.1 (2007): 25-33. Print.

Brooks, Lens, and David Selley. Ethics and Governance: Developing and Maintaining an Ethical Corporate Culture. 3rd ed. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Ethics & Corporate Policy, 2008. Print.

Ciulla, Joanne B. “Leadership Ethics: Mapping the Territory.” Ethics, the Heart of Leadership. Ed. Ciulla, Joanne B. 2nd ed. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2004. Print.

Collins, Jim. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001. Print.

Conscious Capitalism. “What Is Conscious Capitalism?”. 2009. <http://www.consciouscapitalism.org/whatis-conscious-capitalism.html#business>.

Cook-Greuter, Susanne R. “Making the Case for a Developmental Perspective.” Industrial and Commercial Training 36.6/7 (2004): p. 275. Print.

—. “Postautonomous Ego Development: A Study of Its Nature and Measurement.” Doctoral dissertation (UMI No. 9933122), Harvard University, 1999. Print.

Day, David V., Michelle M. Harrison, and Stanley M. Halpin. An Integrative Approach to Leader Development. New York: Psychology Press, 2009. Print.

Fisher, Kurt W., Sheryl L. Kenny, and Sandra L. Pipp. “How Cognitive Processes and Environmental Conditions Organize Discontinuities in the Development of Abstraction.” Higher Stages of Human Development: Perspectives on Adult Growth. Eds. Alexander, C.N. and E.J. Langer. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. 162-87. Print.

Gallup Organization. “Nurses Top Honesty and Ethics for 11th Year”. Washington, 2010, December. Retrieved. <http://www.gallup.com/poll/145043/Nurses-Top-Honesty-Ethics-List-11-Year.aspx>.

Hunt, James, G. “What Is Leadership?” The Nature of Leadership. Eds. Antonakis, John, Anna T. Cianciolo and Robert J. Sternberg. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2004. 19-47. Print.

Hunt, Joanne. “Transcending and Including Our Current Way of Being: An Introduction to Integral Coaching.” Journal of Integral Theory and Practice 4.1 (2010): 1-20. Print.

IBM. “Capitalizing on Complexity: Insights from Global Chief Executive Officer Study”. May 2010. September 3 2010. <http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/ceo/ceostudy2010/index.html>.

Isaacs, William. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. New York: Doubleday, 1999. Print.

Joiner, Bill, and Stephen Josephs. Leadership Agility: Five Levels of Mastery for Anticipating and Initiating Change San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007. Print.

Kegan, Robert. In over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994. Print.

Legault, Marie. “Becoming an Ethical Leader: An Exploratory Study of the Developmental Process.” Doctoral dissertation (UMI No. 3397539), Fielding Graduate University, 2010. Print.

Logsdon, J.M, and J.E Young. “Executive Influence on Ethical Culture: Self Transcendence, Differentiation, and Integration.” Positive Psychology in Business Ethics and Corporate Responsibility. Eds. Giacalone, Robert A., Carole L. Jurkiewicz and Craig Dunn. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, 2005. 103-22. Print.

Mackey, John. “Creating a New Paradigm for Business.” Be the Solution: How Entrepreneurs and Conscious Capitalists Can Solve All the World’s Problems. Ed. Strong, Michael. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. 73-113. Print.

Marquardt, M.J. Action Learning in Action: Transforming Problems and People for World-Class Organizational Learning. Palo Alto: Davies-Black Publishing, 1999. Print.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press, 2002. Print.

McGuire, John B, and Gary B Rhodes. Transforming Your Leadership Culture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009. Print.

Moss-Kanter, Rosabeth. “Leadership 2.0: Strategy and Action for Leading through Change.” 12th Annual International Leadership Association Global Conference. 2010, October. Print.

Porter, Michael E, and Mark R Kramer. “Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism – and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth.” Harvard Business Review (2011, January-February). Print.

Richards, Francis A, and Michael L Commons. “Postformal Cognitive Development Theory and Research: A Review of Its Current Status.” Higher Stages of Human Development: Perspectives on Adult Growth. Eds. Alexander, C.N. and E.J. Langer. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. 139-61. Print.

Rooke, David, and William Torbert, R. “Seven Transformations of Leadership.” Harvard Business Review 83.4 (2005): p. 66. Print.

Rost, Joseph, C. Leadership for the Twenty-First Century. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 1993. Print.

Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday, 1990. Print.

Senge, Peter, et al. Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future. Cambridge: SoL, 2004. Print.

Shamir, Boas, Hava Dayan-Horesh, and Dalya Adler. “Leading by Biography: Towards a Life-Story Approach to the Study of Leadership.” Leadership 1.1 (2005): 13-29. Print.

Shamir, Boas, and Galit Eilam. “”What’s Your Story?” A Life-Stories Approach to Authentic Leadership Development.” The Leadership Quarterly 16.3 (2005): 395-417. Print.

Sisodia, Raj, David B. Wolfe, and Jag Seth. Firms of Endearment: How World-Class Companies Profit from Passion and Purpose. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing, 2007. Print.

Sparrowe, Raymond T. “Authentic Leadership and the Narrative Self.” The Leadership Quarterly 16.3 (2005): 419-39. Print.

Strong, Michael, ed. Be the Solution: How Entrepreneurs and Conscious Capitalists Can Solve All the World’s Problems. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. Print.

Swartz, Jeff. “Leadership 2.0: Action in Service to the Planet and Its Citizens ” 12th Annual International Leadership Association Global Conference. 2010, October. Print.

Thomas, Brett. “Integral Leadership Primer.” International Integral Leadership Collaborative. 2011. Print.

Thomas, Brett, and Russ Volckman. “The Integral Framework.” International Integral Leadership Collaborative. 2011. Print.

Torbert, Bill, et al. Action Inquiry: The Secret of Timely and Transforming Leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2004. Print.

Waldman, David A., and Donald Siegel. “Defining the Socially Responsible Leader.” The Leadership Quarterly 19.1 (2008): 117-31. Print.

Wilber, Ken, and Roger Walsh. “Towards an Integral Ethics.” Integral Naked, 2008. Print.

About the Author

Marie Legault, Ph.D., is President of Legault & Associates Leadership Development Inc. She believes that in today’s complex environment of rapid growth and change, ethical leadership is key in order to find solutions to organizational challenges and achieve sustainability. As a Leadership Development Consultant, Facilitator, and Coach, Marie offers integrated solutions that foster ethical leadership. She assists in the creation of ethical organizational cultures and guides leaders and organizations to develop to their full potential. Marie has a Ph.D. in Human and Organizational Systems, a Master of Arts in Leadership and Training, a Bachelor of Commerce, an Executive Coaching Graduate Certificate, and a Professional Training & Development Certificate. Marie is affiliated with Royal Roads University. She is a dynamic speaker and has written articles for various publications. As a leadership practitioner and scholar, her interests include the development of ethical, conscious leaders and organizational cultures and transformative change. Marie can be contacted through www.legaultassociates.com or at info@legaultassociates.com.