Russ Volckmann

Russ: Barrett, your name is probably very familiar to a lot of people in the core integral group. Integral Leadership Review has many subscribers who are outside those boundaries. So they probably don’t know a lot about you, even though you have shown up in the pages of Integral Leadership Review before with some really remarkable work. I hope we can get to know you a little better. Would you tell us about how you came to your interest in integral.

Barrett: Sure, Russ. I want to first of all start off by saying that I really honor the work that you’re doing and you have done more than anybody I know to help explore the different areas of an integral approach to leadership, get that documented, and make it accessible for people today and tomorrow. It’s an honor to be part of that process…

Russ: Thank you.

Barrett: …and in part of this bigger dialogue as well.

And so how did I get into integral? In 1997 I was working with an incredible man who is a mentor for me. He gave me a copy of A Brief History of Everything and it completely knocked my socks off.

Russ: May we know who this man is?

Barrett: His name is Don Jones. I had been working with him at an organization called the Option Institute. Don introduced me to Ken Wilber, Saniel Bonder, Michael Murphy, George Leonard and other people who have had significant influences in my life. I can point back to Don being the first person to plant those seeds for me, to really have very deep conversations about what’s actually going regarding who I am, how I am going to serve, what’s happening in the universe, what is consciousness, what is God? He was an early dialogue partner for me in that area and a very close mentor.

Russ: I have a Don in my life and I wouldn’t trade him for anything.

Barrett: Yeah, yeah exactly!

So that really blew me wide open. I spent the next few years just reading as much as I could, doing as much journaling and reflection, and trying to apply it to my own personal development. Over the next few years, I began to do more sustainability work. I was also looking at how I apply this. I was involved in a large-scale project to redesign refugee camps as environmentally sustainable settlements. I was supporting an initiative around that working with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, the US Navy, and Rocky Mountain Institute. I was part of a charrette, a design charrette, around redesigning refugee camps as environmentally sustainable settlements.

Russ: What do you mean a charrette?

Barrett: It’s a French word for a design collaborative. It comes from a French word for cart in the days when large-scale architecture structures were being commissioned in France. There was literally a horse drawn cart that would go through the streets of France picking up the designs that architects were submitting for the bid process. Over the years the architects learnt that if they actually jumped on the cart, looked at each other’s designs, made last minute changes, and integrated designs, they would have a better chance of winning together. And so a charrette, a design charrette, is often used in the architectural space where you bring in all different members of the systems. It is essentially a whole system perspective looking at building something.

Russ: Your charrette sounds like an early example of a transdisciplinary project.

Barrett: Yes.

In this case the design charrette was focused on redesigning refugee camps as environmentally sustainable settlements. I had been invited to the design charrette that Rocky Mountain Institute was putting on. I took on the task of looking at if it would be possible to create a global consultancy that would do this work by drawing on this expertise so that we could shift the way the refugee camps are designed and how they’re rolled out. After about six months of significant due diligence in that area, looking at whole system design and using an integral approach to that, I ultimately decided to choose an exit strategy for it. It seemed that the pieces weren’t there for a consultancy nor was there the funding.

But that whole process was very powerful for me, because I experienced what I call cognitive burnout. I think that cognitive burnout is an important developmental event as people are making shifts in their meaning making. I think that it helps people to literally develop more fully in their consciousness. Let me give you a bit more specifics on that.

My experience is – and this is largely coming out of working with many leaders and their struggle with social, environmental and economic sustainability issues–is that in many cases there is an emotional burnout that happens with them. We often see this with folks who are holding more of a green or postmodern center of gravity. Their identity gets tied up with the objectives of what they’re trying to do. Often, they’re working with this big complex system that is very hard to change. Because their identity is tied into their outcomes and what they actually achieve and because the progress is so slow and can be so frustrating, there’s this emotional burnout that happens. It is because they’re not necessarily anchored in a source, right? A deeper unified understanding of being that serves as a grounding for them. Their identity is attached to affecting climate, helping communities be more resilient to climate change, saving the whales, or stopping oil leakages and environmental destruction, right?

People go through an emotional burnout. But what I’ve seen happen to some folks–and I went through this as well–is that past that emotional burnout there’s a cognitive burnout that happens. For me it happened when I was sitting down trying to figure out how do we redesign refugee camps as environmental sustainable settlements using whole system design, using an integral approach, dealing with all of these international politics that are at play. And we were dealing with the fact that this is an incredibly dynamic environment where all of a sudden you can have 50,000 refugees when there’s an area of conflict and there are all these institutions that are already in place that are designed to serve them.

It’s a survival space. It’s a beige-purple-red space, right? Where people are just barely surviving. So trying to get my mind around that and to come up with some sort of leverage points with simplicity on the other side of that complexity, I just couldn’t do it, I just couldn’t do it. And then trying to get that really concrete into an actual economic model and an organization that could execute on all this, I just couldn’t cognitively get around it. I had these massive mind maps and diagrams of how it might all fit together and it just it didn’t.

So I went through a cognitive burnout. And that was depressing and hard and it shook my self identity. Looking back on it now, I didn’t trust the process, I wasn’t willing to fully step into the unknown and move forward with the uncertainty. It was a classic attempt to know the whole system, and figure out how to influence it, without honoring that these things are actually uncontrollable complex adaptive systems.

Russ: Before you go on with the narrative, let’s talk about that for a moment because it seems to me what you’re describing is an experience that a lot of people might have, given the complexity of the challenges we face in the world. This challenge shows up whether we’re talking about it at a community level or a planetary level or anything in between. Our attachment to the myth of the hero frequently causes us to take on the kinds of challenges such as you did, a Sir Gawain effort in conquering the beast and bringing the rewards back to the king.

What we’re challenged to do now is to recognize that the heroic is episodic, that it’s momentary, that it is not something that sustains systems. When it comes to problem solving or opening up new opportunities, we’re increasingly going to need something like your cart. We’re going to increasingly need groups of people from multiple disciplines and ranges of experience to be able to transcend and include their professional and other disciplines to be able to get their arms around this challenges. I’m wondering if you have any reaction to that.

Barrett: Yes, absolutely! All of the major global issues we’re facing are considered wicked problems, meaning that there is no clear solution and they are constantly shifting. It’s a big complex adaptive system that we don’t have any control over. So, yes, part of the process is a multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary approach to understanding the issue and generating a response–not a solution. We can’t pretend to come up with solutions to climate change. We can come up with responses, such as adaptation, resilience and mitigation. Part of it, for sure, is drawing upon the best knowledge from the different disciplines and what they have to offer.

And then another huge part of this is trans-rational and essentially shifting beyond a rational analysis. It requires engagement with the issue and drawing upon what Joseph Jaworski calls in his new book Source, right? Or drawing upon consciousness, collective intelligence or whatever it is that people use to describe the greater self. But there is absolutely a fount of knowledge inside that’s accessible to us from beyond the rational mind. Some people call it intuition. Some people call it divine insight. Whatever they call it, it’s a huge piece of the puzzle. Now it’s also not just that. We can’t just sit and meditate on the ideal and assume it will all work out. I really feel like this is a transcend and include move, meaning we need to use the best of what our rational mind has to offer, what our rational capacity has to offer, and the best of what our intuitive or trans-rational capacities have to offer–even the best of what our pre-rational capacities have to offer in our gut instincts, emotional connections, and the story telling abilities that can bring people together, right? So it is important to bring together the whole being here, all the way up the spectrum of being to respond to these things.

Russ: Well it’s the whole being and it’s the whole context, it seems to me, because if we rely just on the being, then we are in danger of slipping into the monological fantasy or fallacy. If we include context and recognize our sense and meaning making it’s not just something that happens monologically within us, but dialogically in our relationship to the world around us, our life conditions, other people and events, then we have a better chance at being more resilient and responsive and generative dealing with the kinds of issues you’re talking about.

Barrett: Absolutely! I think that’s assumed in what I was saying, because this is essentially a process of engaging with our context and with the specifics of what’s happening here in the moment, I fully agree with you.

Russ: Let’s get back to how you got connected to integral and the work of Ken Wilber.

Barrett: It was 2001 and I had been studying integral theory for quite a while–I guess about four years at that point and practicing it. This was before there was access to anything like Integral Life or any of the recordings or anything like that. I heard about things that were happening in the Integral Institute and had a connection with Mark Palmer. He was in that first round of what were called at the time the integral kids–Mark Palmer, Sean Hargens, John Churchill, Darcy Riddell and a number of other folks. Essentially, they were having dialogues with Ken while Ken was also bringing together luminaries in a variety of different fields for those initial early Integral Institute discussions.

I wanted to get more involved with them. I got Mark to give Ken a document that I had drawn up that would support the development of the Integral Institute. I got proactive about it and I wrote a marketing document that could help to advance Integral Institute as it was growing.

I got Mark to give that to Ken. Mark talks about how Ken was there working on his weight bench and Mark just dropped it right on his chest. Ken said “cool.”

I knew Mark through the Waking Down work of Saniel Bonder. I decided to move out to Boulder with my wife and get more involved in the Institute if I could. I had no job or volunteer opportunity or anything. I just figured that if I were closer I would have a better chance.

There was also a burgeoning Waking Down community that Saniel and Linda were attending on a regular basis. I wanted to be part of that too. And so we just moved; we picked up and moved. My wife and I were deciding where we wanted to live in the US anyway. We did a road trip around the US looking at lots of cities. Boulder was a place that we had decided would be a great place, as well.

There I met Willow Pearson. She was part of that group of integral kids as well. I finally got a chance to meet Ken. It was at an Integral Ecology meeting that Sean Hargens was having with a number of other ecology-minded folks at Ken’s loft.

That was the time when they were talking about setting up different branches, the Integral Institute branches. I was working at that point for an organization called the Sustainable Village in Boulder and as their international development director. That’s how I had gotten involved in the redesigning refugee camps project. I said to Ken, “Look, we need to have an integral sustainability center.” David Johnston was based in Boulder and had done a lot of work in California in the market transformation space. He was helping to move green building ahead in a big way.

David, and then Cynthia McEwen and I, had started to have dialog around the idea of integral sustainability. Cynthia was working with Avastone Consulting [a firm headed by John Schmidt–ed.] and had just finished her master’s degree in sustainability at Bath University in the UK. She studied with Peter Reason, whose work is based in Torbert’s action inquiry, and who had designed Bath’s master’s degree program based upon it. She had gotten exposed to a lot of integral there. [Note: The Bath University program in sustainability leadership has now moved to Ashridge University in the UK and is highly recommended.–Barrett]

And so I said to Ken, “Look, we’ve got this team. David’s got this specialty in market transformation. Cynthia has been working in the business consulting space around sustainability. I am working in an international development space and have interest in both business and in market transformation.”

And so Ken said, “Great! Do it!”

So we were the team that began trying to articulate what the heck is an integral approach to sustainability and sustainable development.

My wife and I concurrently ended up moving back to Vermont where we had moved from, because my wife wanted to get her master’s degree and the best program in her area of interest was the School for International Training in Vermont. We left Boulder, but having made the connection with Ken and with Integral Institute. I became Co-Director with Cynthia and David of the Integral Sustainability Center. Cynthia, David and I had lots of dialogue and explored writing around what is an integral sustainability process.

That’s how it all began.

Russ: After a while you moved to Dallas, right?

Barrett: Yes, I might just as well continue the story.

We had no idea what an integral process of sustainability might look like; and even years later, a decade later now, there is still lots of articulation and inquiry that needs to happen, but we’ve made some good progress. My wife and I ended up moving to Brazil. There she was doing an internship for a master’s degree program that was related to sustainability. We moved to Curitiba, which is a world famous city for its advanced sustainability practices. I had an opportunity to get an embodied understanding of what urban design at a very high level looks like from a deep sustainability perspective.

Concurrently, I started working with Fred Kofman to help translate his three books called Meta Management into what would ultimately become Conscious Business. The original idea was that he was going to launch three books and they were ultimately all consolidated into Conscious Business. I was interested in working with Axialent [Kofman’s international consulting firm ed.] in one of the projects that came up that they needed this translation done. I was fluent in Spanish at the time, and so I oversaw the translation.

During this work, I had the real opportunity to learn about Axialent and what it does with clients. I didn’t end up going to work with them but had a very deep and wonderful connection with Fred, Richie Gil, and the other guys that I worked with there at Axialent. I very much enjoyed that.

We came back to Vermont. I was doing training and leader development work in collaboration with Avastone Consulting and also with independent clients who I had in Vermont. We were also beginning to build the Integral Institute workshops and seminars. So I was working with the Integral Institute at that point. We built the first Integral Sustainability and Ecology seminar, which was six days long, in 2004. I helped to build the I-WET, the Integral Weekend Experiential Training, with Clint Fuhs, Diane Hamilton and Terry Patton. We did a whole road show around the US.

Russ: I went to the first one in San Francisco.

Barrett: Yes. And then I was on the core team that did the Introduction to Integral Theory courses that were at the beginning of every single Integral Institute five-day seminar.

At this time I had this naïve thinking that if I just got in and learned about integral theory, then I could really be a global expert. I could go and fix things and change people, like integral theory was all I needed. I threw myself deeply into it. Pretty quickly I came to realize that the people who were going to have the highest impact with the use of integral theory were people who were already world class in their particular vocation and were applying integral as part of that.

I realized that I needed to start on the path to becoming world class in a particular vocation. That’s when I decided to get a PhD in organization development, specifically in human and organization systems through the Fielding Graduate University. I decided to throw myself deeply into doing organization development work and was fortunate to get an opportunity to move to Dallas to work with Stagen [the leader development and organizational consulting firm founded by Rand Stagen and Brett Thomas–ed.]. I helped them to build their organization development practice.

Russ: So you were not coaching in the leadership program? You were working with the organization development practice?

Barrett: Yes. I wasn’t involved at Stagen in their integral leadership program as much. I was helping them to actually create a broader set of consulting offerings.

Russ: Right, which is very important in their operations today.

Barrett: Yes. They have essentially three main tracks–their integral leadership program, their organization development practice, and their management consulting and operations practice. They’ve woven those together for clients, tailoring what each needs from those three tracks. I had the pleasure and opportunity to work with some very senior and talented organization development practitioners there, including Rick Vorin and Michael McElhenie.

It was a really an awesome environment to be learning a ton about OD in the field while I was concurrently in a PhD program about it. And then, I was also learning a bunch around the management consulting operation side from Wes Blair, Mark Hass and the other brilliant folks who were attracted to the Stagen environment.

Russ: They brought in some pretty heavy hitters from big consulting firms.

Barrett: Yes they did. That’s part of their magic.

From the strategic side they are able to bring in folks who had a lot of experience to complement the organization development work. So at that point I stepped away from the integral sustainability work and, frankly, I went through a period of doubt around is it effective, is it practical, are we really able to do anything with it? Concurrently, I had to continue to be the co-director of the Integral Sustainability Center. We had done a very successful five-day seminar in 2006 on Integral Sustainability, but at this point I just shifted to full focus on my PhD program and working at Stagen. We had a baby at that time, as well, so my plate was full.

After a number of years at Stagen, I had a desire to more deeply engage in the sustainability work again and, specifically, to work with large scale systems, because I could see what was happening regarding our social and environmental challenges. The work at Stagen was absolutely fantastic in helping to develop leaders in organizations that are more tuned in and turned on and are waking up and growing up. Yet I was seeing that, at least from one perspective, the world was still falling apart.

And so what could I do? Could I go and learn about large-scale systems and market transformation to contribute somehow? I got very clear at the Integral Theory Conference in 2008 that I wanted to make a significant shift in what I was doing. I put the intention out there and had dialogue with Peter Merry at the Conference. Peter was living in Holland and leading the Center for Human Emergence there.

I made a very clear intention saying I wanted to focus on building and doing two things: building systems and structures to support the emergence of global sustainability and developing leadership to engage and operate in those systems and structures around global sustainability. I said that that is what I wanted to do, I put the intention out there and within six weeks, Peter sent me a job opportunity that came up in the Netherlands. It was an opportunity to work with this new organization that had 30 million euros in funding to do supply chain sustainability. They had to spend the 30 million in just a few years, funding market transformation. They were going to do public-private partnerships in an innovative way to mainstream sustainability into global supply chains. They needed someone to drive the development of their learning systems around that.

I was one of 50 applicants. I was the only expert or the only international person applying against a bunch of Dutch folks and was fortunate enough to get the position. So our family picked up and moved to the Netherlands. It was our second international move at that point, but this time with our young daughter. I took a significant pay cut to go and do it from what I had been receiving at Stagen. My wife’s career had to be restarted there as well. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but we just wanted the experience of going and living in Europe. I wanted the experience of doing large-scale market transformation work and so we just went and did it.

While there, I saw a whole other side of integral, called “folk integral”–a term Gail Hochachka came up with. It refers to when integral is naturally arising even though its not informed by the formal integral theories of Wilber, Torbert, Roy Bhaskar, Egar Morin, or any of the other integral theorists out there. Folk integral is a very important thing to pay attention to because it points out that it really is a developmental stage. It’s not just a theory. It’s a developmental stage people are evolving into and beyond.

Russ: One of the things that I think is frequently confusing–and this applies in the field of leadership and the field of integral as well–is that the same term is used to indicate different things. Leadership, for example, can mean a myriad of different things and integral is used to describe Gebser’s stage of development and to describe a meta theoretical orientation. When people are talking about integral, its often confusing as to which they’re talking about. I know your dissertation had to do with people who are at advanced stage action logics, people who are already in the developmental realm of integral as a stage. I’m curious how the two go together in your mind–the fact that you’re dealing with a meta theoretical perspective and you’re dealing with the notion of one of a number of stages of development. How does that fit together with the work that you’re doing?

Barrett: Well, I guess I cheat, because I don’t really think of the later stages of action logics as the integral stage of development. When I think about integral from a meta theoretical perspective, I think about the theories of Wilber and Roy Bhaskar, Edgar Morin and Mark Edwards.

Now that is only in the “integral world,” right? In the mainstream the word is used all the time. What they are talking about is a multi-disciplinary approach using mostly lower right disciplines to figure stuff out. So, for example, there is a huge call in the international community in major reports that come out that are essentially asking for these integrative approaches to international development issues, climate change, and poverty alleviation. Everybody is calling for integral approaches: get rid of the silos, get rid of the lack of alignment and really come into a cohesive, efficient, and integrated approach.

But the vast majority of what they are talking about is aligning the systems, structures, and sciences that focus on the lower-left quadrant, maybe adding in some anthropological insights. They aren’t talking about the full integral perspective that Wilber’s theory would offer. So I use integral differently depending on the context.

Russ: In the Netherlands were you developing programs in integral leadership? Did you do training programs?

Barrett: There was my day job and there was what I did on the side.

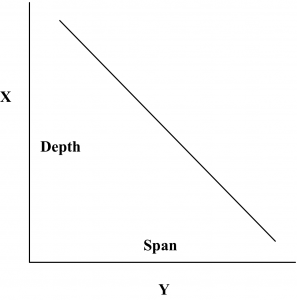

Let me explain a simple frame first. If you take two axes where one of them–your X axis–is depth of development and your Y axis is span. How many people can you actually reach? If you draw a line that goes from the top of the X axis to far out on the Y axis, you have a triangle. That is a very useful framework to think about learning, because what it says is that if you want to do depth work you can only do it at a short span with a small number of people.

If you want to do significant learning across a wide span you cannot go that deep, okay? So when I was working at the Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative, we were working with entire global supply chains – the entire cocoa supply chain, all of aquaculture, soy or tropical timber. We would–to use Adizes’ concept–use CAPI: Coalesce the Authority, Power, and Influence in that system. We would bring together all of the multinationals, the relevant governments from the North and South, as well as the international NGOs and academia that had expertise in that sector. We focused on market transformation of that sector, striving to accomplish very specific social, environmental, and economic objectives. We built large-scale programs to go after this. For example, in the tea sector, where we did a lot of work with Unilever and the Rainforest Alliance, we worked to get 250,000 farmers in the tea sector in Kenya certified in Rainforest Alliance production practices, which are essentially good agricultural practices that would make their tea more marketable in the consumer countries.

That involved working with lots of people, lots of procurement managers within companies. The level of training that was required to help advance the whole system rapidly was basically best practices and innovation sessions around tough issues. It wasn’t the sort of depth work where I had the opportunity to deeply engage around leadership issues with small groups and individuals. So most of my work was building learning systems, helping these sector groups of business, government and civil society to achieve their objectives and learn from the case studies that came out of it.

For example, we did a case study with IMD Business School that I produced with Unilever and the Rainforest Alliance. It became the award winning case study within the European EFMD, which is the European Framework for Management Development. That’s the big European clearing house for case studies. It won this award in the supply chain category for best case study and is now taught at IMD and I assume other universities.

And so I did stuff like that. I designed and rolled out innovation sessions, for example, where we would bring in leaders from West Africa in the coca sector as well as members from Cargill, ADM, Nestle and Mars–senior executives who had authority, power and influence in that space. We would go after very tough technical questions like, how do we organize 800,000 famers in Cote d’Ivoire to take on advanced agricultural practices and improve the sustainability of that sector, while at the same time minimizing the cost throughput for the supply chain as a whole from doing the development work?

Russ: It sounds like your integral intelligence, if you will, more than anything, might play the role of keeping your limits and boundaries clear in that process.

Barrett: Yes. Basically, the context did as well. There just wasn’t the time to do depth work with these executives from Mars or Nestle because they were completely overwhelmed, completely pressured to hit these large scale objectives. So I would do a little bit of mentoring and coaching along the way, sometimes with them, sometimes with the NGO leaders that we worked with and, more often than not, with the program managers from the foundation I was working with, because I had more daily time with them. I worked very closely with them.

At a certain point I began to feel desiccated in that I wasn’t doing as much depth work for myself and for others in leader development as well. Beena Sharma suggested to me to just set up an integral sustainability course where I could do really deep work with people and practice different modules. It would be an opportunity to do significant leadership work that was related to advancing sustainability.

And so I did that. Over the next few years I ran a number of experimental courses in the Netherlands that were sometimes 8 months long, sometimes four months long, sometimes 10 weeks, while trying out lots of different modules. I ran it through The Hub Amsterdam, which is a social entrepreneurship platform that is emerging worldwide. I also partnered with the Center for Human Emergence to deliver them. I was able to do those programs as a way to complement my need for doing depth work with people. The large scale work was just exhausting at times and wasn’t always personally rewarding.

Russ: When you reflect on that experience, are there key learnings with regard to integral and leadership that emerged from that series of activities?

Barrett: Yes, for sure! One of the key things that I realized at the Dutch Sustainable Trade initiative is the power of alignment of worldviews toward a common objective. What I mean by that is that what we managed to do was to connect and align with disparate worldviews, such as government, business and civil society – which you could loosely map to amber, orange and green. We got folks aligning toward a common objective and taking action toward that without needing them to be different than who they actually are.

So this is the core Clare Graves concept. Graves has that famous saying “Dammit! People have a right to be who they are!” What we found is that that actually works. Specifically, the way that market transformation has been attempted in the past in lots of cases is that NGOs hammer businesses to actually care and to act like they actually cared, meaning the NGOs wanted the businesses to care for the deforestation that is happening in Indonesia. They wanted businesses to care for the environment, the corals that were being destroyed by oil slicks. They wanted them to care about the poverty endemic in Africa, or in some parts of the Americas or parts of Asia. And so they would hammer them to take on the NGO’s worldview and care and act from that space. That maybe worked to a certain extent, but there was never full engagement by business for the most part.

What our initiatives did was allow business to show up, invest and engage in these market transformation issues for their own reasons. They were there for what we called enlightened self interest, meaning that they–for example; Mars and Nestle and Unilever–would show up, not because they fundamentally cared and that was at the center of their business model, because it wasn’t. There are definitely people within those systems that fundamentally cared about poverty in Africa and deforestation. Of course there are. But most of the folks that I worked with were in these systems because their organization had very specific business interests in advancing these market transformation initiatives.

They were there for supply chain security, for risk mitigation, for brand reputations issues. They were there essentially to create a more efficient supply chain that secured access to an increasingly rare commodity such as certified cocoa or certified tea. So there was a real business interest. They were there to protect their brand, because, as you know, a huge percentage of the valuation of a company–especially a public company–is their brand. It has been estimated that 60% of McDonald’s market valuation is its brand reputation. So these businesses were there for that and the risk mitigation standpoint, as well. Many decisions at board levels are made through a risk mitigation lens. They were to mitigate the risk of major environmental or social issues in their supply chain that would then impact the marketability of their products.

These are, of course, very orange level reasons for engaging in sustainability. We didn’t need them to have more enlightened reasons or more moral reasons. We said, “Great! You are at the table.”

The NGOs–WWF, Solidaridad, Oxfam–were there for true worldcentric reasons, as well as for their own institutional interests. They were there to advance the millennium development goals. The governments were there for a variety of blue, orange, and green reasons as well. In the Netherlands they tended to be there because they authentically wanted to advance the livelihoods of farmers in Africa. They were interested especially in those who were related to supply chains where there were a lot of Dutch people working, like cocoa or soy. Southern governments were there for the economic development aspects, as well as to secure votes for their parties. And of course there were folks involved with Red, or egocentric interests as well. So it was a full-spectrum group of folks engaged, with varying value systems, yet aligned toward collectively achieving our common social, economic, and environmental targets.

My key takeaway was that it is possible to create objectives that align different entities like business, government, and civil society who had different reasons for coming there with different world views and they still could take coordinated action together.

Russ: This seems very much like the objectives of Don Beck’s Meshworks and simulcasting practices that come out of Stagen. This involves being able to take a very different kind of approach to differences in social systems and find the ways to align energies around themes that have different meaning for the different sub groups within those systems.

Barrett: Yes, absolutely.

Russ: That is a talent and a skill that far too few people have. Where would you see people going to learn how to do something like that–how to work with people in that way?

Barrett: Well, the Netherlands have really got this figured out, because of what is called the polder model. Polder is an area of land out of which they have to “polder off” the water, out of which they have pumped all the water and literally created the land. The Dutch did a lot of this. They created an entire country out of a bunch of wetlands and marshes. In order to create these polders, you have to set up dikes around them that keep the water out and you have to have pumps that are constantly going. So the Dutch have 6000 large scale-pumps that are constantly pumping water out. If for some reason all of them shut down simultaneously, something like half of the country would be under water in six hours. So it is a significant engineering feat to maintain this battle against gravity and nature and water.

But with all these dikes set up, the communities within the polder, surrounded by the dike, had to come together to figure out how to manage this polder on a day-to-day basis. They literally had to develop consensus-driven action. Now, people would do it for different reasons, but at the end of the day you have to have aligned action. This has become called the Polder Model, which is essentially getting aligned action no matter what your reasons. The Dutch are really really good at this.

I think it is one of the things that has accelerated the overall center of gravity of that society beyond orange–they have had to do that for so long. I went to the Netherlands because I was really interested in understanding this leading edge way of engaging in sustainability in leadership and in market transformation. I learned a lot there. Now the Dutch have all of their own issues as well, they are certainly not perfect and have their own unhealthy societal expressions as in every country.

Russ: So does everybody have to go to the Netherlands to learn how to do this?

Barrett: No, I don’t think so. David Johnston did a very similar thing out here in Alameda County in California by cultivating market transformation in the building industry. There are people doing this all over the world. It is becoming more and more common. I think what is more important is to go and work with a mentor who has done this before and is doing it in order to see how it is being done. That being said, the crucial element to this process is having leadership that doesn’t have a psychological “charge” around people who hold an amber/blue, orange, or green worldview. As soon as you begin privileging those and noticing only the disaster of those worldviews and not also noticing the dignity of them, then you create blockages for your ability to communicate and be in resonance with people who hold those worldviews. There is a huge amount of internal work by each individual that needs to be done to clear that out.

Russ: That seems to tie directly into your dissertation because you were looking at people who were at advanced stages of meaning-making, or late-stage action logics. You ended up with 13 individuals for your study, as I recall. There were Strategists and above.

As we both know, the percentage of the people at those higher action logics is pretty small in the world. Finding enough of those folks to do all the things that need to be done is a real challenge, especially using the model that we have just been talking about. The people that you studied in your dissertation were both people in formal leader roles as well as people who are change agents . . .

Barrett: Yes.

Russ: And you treated them all as leaders.

Barrett: Yes.

Russ: I would like to hear a little about why you considered both groups to be people in leader roles; and then, secondly, what is the level of hope that you have that we can address these issues when the number of people who are able to take on that perspective of valuing those other worldviews is so small?

Barrett: First of all I interviewed 32 folks and assessed them all with a version of the Washington University Sentence Completion Test, which has been significantly validated and identified their center of gravity around how they make meaning. Thirteen of the participants ended up being assessed with these late stage action logics, which essentially correlate to teal, turquoise, and indigo in Wilber’s stages of consciousness model. So they are really late stage folks. However, there are another nineteen folks whom I interviewed that didn’t assess at those later stages. They assessed at the Strategist and Individualist action logics, which correlate to Orange and Green in Wilber’s model. Regardless, these were very effective people. These were people who were in some cases leading some of the largest sustainability initiatives on the planet and they assessed at an earlier action logic than others.

I want to point out that there is a myth that you can’t be effective as a leader unless you have reached these later stages of development. There are lots of people being very effective in leadership positions that hold an Orange or Green center of gravity. I have that from empirical evidence. I can’t reveal who the leaders are that I interviewed, because that goes against the confidentiality of the dissertation process, the research process. But clearly there are people out there doing amazing work at a very high level within companies, government, and NGOs, and they happen to be doing it from conventional and early post-conventional action logics, the Achiever and Individualist.

I have to also make another note that just because someone is assessed using the sentence completion test at an Achiever and Individualist action logic doesn’t mean that they aren’t also able to access later action logics. In some cases it is simply a data point from a moment in time. It is important to point that out. So it may mean that these folks are tapping into later action logics as well or they were just mis-assessed. But I can only work with the data that I had and I only chose to work with folks that had been assessed these later action logics.

There is a qualitative difference in how folks explain what they are doing and why they are doing it if they are Achievers or Individualists as compared to those have later action logics like Strategists, Alchemists and Ironists. There really does seem to be more depth flowing through this latter group. However, so much work needs to be done from a leadership standpoint and a from sustainability standpoint, that clearly Achievers and Individualists are able to do exceptional work.

When I worked at Stagen and we would do leader development and organization development programs we would go into mid-market companies. Often, they just didn’t have in place the good and best practices that are available around team building, innovation, learning systems, economic models, recruiting and the like. In many cases we weren’t necessarily doing super advanced stuff with them. We were just helping them to get good, to get to the next developmental stage of where they needed to be, which happened to be the orange level. In global sustainability, in global leadership, a lot of the work that still needs to be done is putting in place best practices and you don’t need to have advanced action logics to do that. I do think that the really complex designs, and intricate and sensitive stakeholder engagements, and engaging in wicked problems effectively–all would be well served by people who hold later-stage action logics–as long as they also really are skilled in their profession and know their industry well.

Russ: One of the things that I have been tapping into more and more over the last couple of years is how the distinction between managing and leading is a valid distinction, depending on how you differentiate them. But the developmental aspects of both involve capabilities, skill development. Some of these skills are foundational for both, particularly self-management.

Whether we focus on productivity management or what some people might call time management, that will help you in the role of a manager but it also will help you in the role of a leader. Other skills would include after action reviews, stress management, and so on. When you talk about best practices as being foundational I think that makes a lot of sense.

Barrett: Yes. That being said, even the complexity of what we face on a global level around our leadership issues, whether they are at a community level, at an organizational level, at an inter-organizational level–like a sector or intergovernmental level–we need best practices or good practices in place and we need really deep innovative work that is maybe only possible by folks who hold these later stage action logics. Even though the percentage of folks who hold these later stages of action logic is so low, I do have a lot of hope that we are actually going to move forward through this. The reason for that is because first of all there are lots of good practices out there that still need to be put into place and those are going to make a big difference.

Second, the environments–or Life Conditions as Don Beck would call them–that people are in are so complex that development is happening whether they like it or not. People are being forced to learn faster than ever and learn more than ever. Some of that learning is transformational, not just translational. Some of it is vertical development and some of it is horizontal development. I think that the distribution of leadership and the movement of leadership has already shifted from the knight on white horse or the Sir Gawain and the Green Dragon model to models like distributive leadership, co-leadership, and just in time leadership. Barbara Kellerman, of course, is talking about the End of Leadership in her new book, [KH1] and she’s pointing to this trend, among other things.

We are co-creating an environment where more and more people are able to provide leadership that is needed in the moment and that’s more and more accepted. So it’s becoming increasingly common that the plant managers’ voice is being heard at the board level. It’s becoming more and more common that the customers’ voice is being heard, that the environmental perspective is being taken into consideration. That’s happening with greater frequency every day in many parts of the world. That’s part of what gives me hope–the diversity of vantage points that are being brought in on regular basis . . .

Russ: Stakeholders of all kinds.

Barrett: Yes. They are driving solutions that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. They are driving development of the very people that are in those systems by being exposed to all those perspectives.

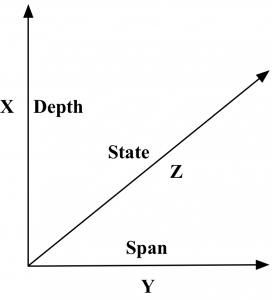

Anyway, we’ve moved back to the US now, specifically to the Berkeley area. It’s for a whole variety of reasons. From a career perspective I had become clear that I wanted to be doing more depth work with leaders on a more regular basis and not to be doing a large-scale somewhat flatland approach of working with complex systems. I will continue to work in the development of complex systems, but I really feel like my strength is in building liberating structures for leaders that help them to not only do vertical development of their consciousness but also horizontal development of the key skills and competencies that they need, and state development of their executive presence.

You can imagine the Z axis of state structure development. Combined with the X and Y axes of vertical and horizontal growth, those three really are what I’m interested in focusing on. My interest is in going much more deeply into that space in service of the alleviation of suffering and in service of the development of consciousness.

Russ: How are you going to do that in the world?

Barrett: It will happen in a variety of different ways, including working with Sean Esbjörn-Hargens at MetaIntegral. MetaIntegral is fundamentally an ecosystem of three organizations. There is a foundation, an Associates–which is a consultancy practice–and there is an Academy. The Academy and the Associates are for-profit entities and the Foundation is nonprofit. The foundation will have underneath it a number of integrally informed branches that are focused on the application of a MetaIntegral approach to disciplines like business, sustainability, ecology, health and medicine, education, art, et cetera. So it’s an expression of the original idea of the Integral Institute.

The foundation is going to be doing all sorts of other stuff as well with respect to investing in integral research, investing in international development initiatives to advance large scale objectives. The Associates are going to focus on deep application of a MetaIntegral approach to advancing organizational issues in a wide variety of disciplines. The Academy is going to focus on the development of embodied practitioners to help driving those sorts of initiatives.

I am working to build this up with Sean at the lead and a number of other amazing folks involved like Joel Kriesberg, Alan Watkins, Jordan Luftig, Nick Hedlund, Willow Dea, Carissa Wieler, Logan “Mikyo” McLellan, Mark Forman, and Michael McElhenie. We’re also talking with some remarkable colleagues like Dean Anderson, Diane Hamilton, Dana Carmen, Beena Sharma, Alain Gauthier, and Allison Conte–as well as many others–to be part of the consulting work we will be doing in some way.

We will also be offering through the Academy embodied practitioner programs that essentially give people the capacity to really engage with a MetaIntegral approach to advancing key initiatives that are of importance to them. Similar to the way that Integral Coaching Canada has developed an integral approach to coaching, we are going to develop what we are calling a MetaIntegral approach to being a practitioner in any field.

Russ: Why the combination of terms–of Meta and integral?

Barrett: Well, for the reason that there is a field of integrative thinking and integrative action that is beyond the way that Wilber has articulated it so far. Ken has gone the furthest to articulate a large integral vision and help it get concrete in its application.

Russ: For vertical development.

Barrett: For vertical development–a lot of it specializes in that space, yes. However, there are other integral approaches that specialize in other areas. So you can loosely say that because of the inclination that Ken and many in the integral community have toward consciousness and deep psychological development that the center of gravity of the AQAL integral model leans more toward the upper left, leans more toward the interior of the individual.

Russ: Exactly.

Barrett: Of course there is great work that is being done in the application of integral in the other quadrants as well, but if you were to look at the center of gravity, its greatest strength is in the upper left, correct?

Russ: Right.

Barrett: If you shift then to another great integral theorist–Roy Bhaskar–who is based in the UK, has taught at Cambridge and is a very respected and globally known philosopher, he developed the field of critical realism. And critical realism is an integral approach that if you look at it, if you step back away from it, privileges the lower left predominantly. Finally, there is another well known integral philosopher called Edgar Morin who is French.

Russ: We published a piece by him that was translated by Basarab Nicolescu in the March issue of Integral Leadership Review.

Barrett: Morin’s work is also an integral approach, but it has its center of gravity much more in the lower right. He is coming out of the complexity sciences, and he has this sort of post-post-conventional complexity approach to the work that he is doing.

If we can figure out a way to marry these three – Wilber’s work on integral, Bhaskar’s work on critical realism, Morin’s work on post-post-conventional complexity–then we have this MetaIntegral approach that takes the strengths of each of these different disciplines and brings them down to very concrete, very useful, and applicable practices that will help to advance not only the development of consciousness but the development of we space, cultural work, and systems as a whole. So that’s the vision essentially.

Russ: That’s really exciting. This is moving exactly in the direction that seems to me to be appropriate and needed and long overdue. I congratulate you guys for taking this on, because it’s going to be a challenge and hopefully great things will come from it.

Barrett: Yes, and it’s frankly a thousand year project.

Russ: Ah, like Stuart Brand’s (Whole Earth Catalogue) ten thousand-year clock project. I published an interview with him last year in Integral Review.

Barrett: Wilber has done incredible work in making his theory as accessible as possible and as practical as possible. There are tons of other practitioners who have taken it even further and really fleshed it out into different disciplines. Edgar Morin’s work requires taking additional shifts in its applicability, although there are plenty of people out there who are doing that concurrently as well. Roy Bhaskar’s work, as well the whole field of critical realism, is being applied to many different disciplines in the academic sphere. It is being translated into practitioner friendly ways of working with it. There is a whole book that just came out that looks at the application of critical realism to organizational management.

Russ: I’m finding a lot of Morin’s work is not available in English.

Barrett: Well, it’s not. It’s mostly in French. One of the projects of the MetaIntegral Foundation is translate his magnum opus–a seven-volume series–into English. That’s one of our first projects here.

Coming back to what I’m going to do and how I’m going to do it, I am specifically going to be working with other thought leaders in the field of an integral approach to leader development in order to craft and execute practitioner and leader development programs that support the development of not only people’s meaning making but also their ability to access profound state capacities, such as embodied presence.

The embodied presence work will be similar to the work of Tony Schwartz’s power of full engagement – that corporate athlete physical state capacity. Then, of course, the classic Eastern capacity to access later states structures going back into the core zone as a way of supporting your leadership. Ideally, it will focus on energy management, intention management (tuning into your core values), and attention management (e.g., meditation).

So there will be the vertical development work, the state development work and then where it’s relevant we’ll also focus on the needed competencies and skills, the needed horizontal learning for 21st century leadership. So, in those cases we will work with things like being able to understand and apply a complexity approach.

Lots of people are focusing on the horizontal stuff so we won’t be doing as much of that, but in the overall frame those three axes are absolutely vital. Our approach will embrace all of them. So we will be developing those programs with weekend workshops and weeklong events and one three-year program.

Russ: Did you say one three-year long program?

Barrett: Yes, there will be a three-year long program that can be taken a year at a time.

Russ: So you are breaking away from the notion that leaders can be developed in a weekend or a week or something like that. It is more of a lifelong learning process.

Barrett: Yes. I have witnessed my wife go through the Integral Coaching Program over the past couple of years and become certified as an integral coach. I have seen the power of what that long-term program can do to support the development of consciousness and capacity. I have been in a lot of dialogue with Terri O’Fallon and the work that she has been doing with Geoff Fitch and others at Pacific Integral. Their Generating Transformative Change program is remarkable and is cultivating significant change in folks in nine months.

But at the same time there are lots of people who can’t engage in a three-year long program and so we are going to offer online programs and weekend initiatives and weeklong workshops, as well.

Russ: We’ve taken almost twice the amount of time that I thought we were going to do in this interview and clearly there is lots that we could have talked about that we didn’t go into. I expect there are tons more we are going to be learning from you and Sean and others who work with you as the years unfold. I truly hope that there is some way that the word can get through Integral Leadership Review about the work you are doing and the things that are happening with your efforts. So I hope this interview will be a first step in that direction.

Barrett: Well thank you, Russ. It is an honor to be a thread in this emergent beautiful tapestry of integral leadership, to be able to contribute my particular take on what I’m learning from the remarkable people that I have the opportunity to study and work with. It’s very rewarding.

I really commend you for creating the container, or maybe it’s even that you’ve been creating a loom upon which many of these threads are being woven together into this tapestry and then just allowing that tapestry to weave itself.

Russ: I think of it most often as a channel in which there are many tributaries leading to the ocean of wisdom.

I hope that is not too pretentious.

Barrett: No, it’s great.

Russ: Thank you very much, Barrett. I very much appreciate your work and your spending the time with me. I hope we get a chance to talk again soon.

Barrett: I look forward to it. Take care Russ.

About Barrett C. Brown