Marc G. Lucas

Marc G. Lucas

This article aims at providing a systematic overview of the concrete forms of appearance of and options for an emergent integral leadership research and related theory construction. First, the integral approach is described by its origin and validity claims. Then – in terms of a multi-theoretical approach – it is made available for academic research. Deliberately, this is not an attempt to deliver one more contribution to integral meta-theory. Perspective and objective are particularly characterized by the effort of making integral research “sciential”.

1. Epistemological Foundation

The integral approach has a relatively short tradition in the field of academic research and theory construction. Furthermore, there is still no clear definition of the term “integral” (Leithoff and Lucas, 2011, p. 111). The term “integral” shall first be defined a) holistically according to its “comprehensive nature and b) integrally according to a structuring “integration” of perspectives on the respective subject of research. Consequently, if one understands integral theory construction as a process which assumes the possibility to increasingly integrate knowledge in (social) sciences theoretically and meta-theoretically, the creation of heuristics and framework systems plays a new role. From a long-term perspective, scientific trends and developments are recognized as a dialectical process between phases of differentiation and integration. Epistemologically, one can differentiate a rising spiral pattern toward more complexity between phases with the emphasis on precision and phases with the emphasis on (the maximum) importance as dialectically related requirements for theory construction.

The following remarks serve to deduce and illustrate a basic multi-theoretical model for an integral approach. However, the author does not adopt a meta-theoretical position. This has already been illustrated plausibly by Deeg et al. (2010).

A meta-theoretical analysis can arrange various leadership theories in an integrated model but gives no statements at the object level except for some references to meta-management considering all model entities. Thus, it highlights the subject and assigns it the totality of existing theories in as simple and consistent as possible framework model. This meta-analysis is thus holistically and holonically oriented, but cannot be holarchically[1] in the strict sense of the word because the stages of specific developmental (and psychological) theories at this level of abstraction may not be applied to specific subjects of study, but only reflected in their internal logic.

An integral approach understood in this way (Deeg et al., 2010; Edwards 2009 and Esbjörn-Hargens, 2010) must be understood as a heuristic that facilitates the access to complex problems through an appropriate systematization. The basis of the research is a multi-perspective and system(at)ic integrative orientation. The claim of integral meta-theoretical construction is to establish an ordering, but also developable, heuristic with the aim to limit the current scientific and application-related fragmentation into sub-disciplines, minimal statements and point solutions, as well as the reduction to only mono-perspective approaches as far as possible and reasonable.

This article shall also apply leadership to a multi-theoretical theory construction through integral models as considered possible and worthwhile by Edwards (2008, p. 192). This multi-theoretical analysis is thus deduced from a meta-theoretical heuristic. However, it can, compared with a sheer meta-theoretical analysis, consider the phenomenon “leadership” through different theoretical approaches in an integral model at the object level and deduce verifiable hypotheses. In this way, it enables empirical research.

The starting point for integral modelling is an approach that is based on the reduction to basic entities of the research subject and then makes an attempt to reconstruct the different perspectives on this subject of research by context creation. Integral multi-theoretical constructions thus not only provide – as is already done under various earlier models in social sciences – an integrating systematization, but also have their specificity in an already existing and proven multi-perspective holonical synopsis (Leithoff & Lucas, 2011, p. 113).

The basis for the epistemological considerations is Merton’s (1998) representation of a continuum for sociology and, in a larger sense, also economic and social-scientific disciplines. Most often, it is mistakenly referred only to the rejection of universal theories. Merton, however, expressed than one should, if you cannot meet this demanding program of eternally valid theories, not tend to the other extreme to raise only social facts and discuss on a case-by-case basis. By no means does Merton talk about antagonism between universal theories and empirical research. He recognizes the possibilities of social science research in the entire middle range (middle range theories) between theories of high levels of complexity and high levels of abstraction on the one hand and demand research on the other hand as it may prevail nowadays in the effort to address methodological precision. This thinking in continua instead of antagonisms forms since the positive change introduced by Seligman and Antonovsky, in total a new position also within psychology, and provides the basis for a broader more developed and thus a more integral new understanding of the importance of Merton’s scientific theoretical continuum.

From a research-historical perspective which in a dialectical sense detects and recognized movements between the extreme poles of this continuum, the author sees the resurgence of frame models as a hint for a tendency to the integral. Amongst others, such meta-synthetic approaches can be seen lately in neurosciences (Caspers et al. 2011), in organizational stress research (Belschak, 2002, Backer, 2007; Wilde et al., 2009) and personnel management (Avolio et al. 2009; Brown, 2011; Hernandez, 2011; Lessem & Schieffer, 2009) that are systematized only by the integral approach (Deeg et al., 2010). On a methodological level, this broader perspective is completed to a more inclusive continuum of research methods by recent meta-methodical considerations (Bradbury & Bergman-Lichtenstein, 2000, Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Esbjörn-Hargens, 2006; Niglas, 2008; Niglas et al. 2010) to which reference is made at this point.

The relevance debate introduced amongst others by Rosenstiel (2004) regarding economic psychology may be, at least in German speaking regions, an impulse for this development, but should at least have been an expression of it. It repeats a criticism that was already introduced by Raynaud (1954) as a criticism of the “department store” character of economic psychology. If nothing else, the increasing complexity of the working world certainly has a high importance as driver of such tendencies. Particularly economic and social psychology – especially in the Anglo-American expression as “organizational behaviour” (behaviour in and of organizations), of which leadership psychology can be considered an aspect – offer numerous connection options because they are considered an integrating cross-sectional discipline with the aim to set up applied but also broad approaches to dealing with experience and behaviour of people in the social context of an organization. As such, they always integrate the suggestions from psychology (especially personality, developmental and social psychology), business administration (human resources management and organization), sociology and more recently of neuropsychological economy.

The current goal of business psychological theory construction thus may be to create theories and framework models with the largest and most reliable meaning possible. These limits are, however, fluent due to the increasing knowledge gained that drives scientific theory construction through phases of integration and phases of backup. Limit violations exist currently in the extra-large fragmentation (precision absolutism), whereby the statement content of theory and research is lost on the one hand and the extra-large object choice (e.g. integral philosophy after Wilber, 1996) on the other hand, has led to ideological and not provable theories. The author thinks that especially due to the frequent lack of verifiability and the explicit self-reference of such “theories” the door is opened for pattern recognition without an underlying convergence. In this sense, one must assume a danger of “patternicity” according to Shermer (2011, p.59), i.e. the error-prone basic tendency to recognize patterns even where there are no connections.

In a dialectic sense limit violations also represent necessary antithetic reactions to the scientific mainstream. However, these could only prepare the way to a new more integral synthesis. If one looks at the totality of so-called integral literature, one can actually differentiate four different tendencies of integral thinking, which in part must be considered incommensurable – something that so far has been recognized too little. Therefore one must differentiate between:

- Meta-theoretical approaches

Such approaches meet the criteria of a meta-theory by making fewer statements at the object level and only reflecting about the internal logic of theories and the possibility of statements. They are more descriptive. However, their comprehensive framework also makes references to omissions and blind spots of economical (psychological) research are possible (Scharmer, 2009)

- Multi-theoretical approaches

They enable the largest span and ability to integrate at the subject level by using a previously developed integral heuristic to consider existing models and theories. Such rather explaining models, however, run the risk of losing their elegance due to too many extensions and being recognizable only as a loose collection of random content due to too little internal consistency and too much self-reference. There is also the risk of an immunization tendency i n the case of confusion with a meta-theory, this means if the theory used is confused with a metatheory and sets itself out of the scope of a theoretical analysis and critical reflection or makes both metatheoretical reflection as well as predictions on the object level.

- Mono-theoretical approaches

They represent a special case of multi-theoretical approaches, since an individual theory represents the basis of the broad explanatory potential. These approaches avoid the problems of incommensurability of independent theoretical constructs. They offer the best opportunity for a self-contained analysis, but are insufficiently open or too distorting in relation to other knowledge.

- Monistic-spiritual approaches

These approaches were especially and increasingly pursued in the early phase of integral efforts. A late, but important example in particular is Wilber’s integral philosophy[2]. As already mentioned, these rather ideological approaches entail the risk of total ideologization and often cannot be analysed scientifically.

Newer integral approaches are conscious of their position in this meta, multi and mono-theoretical area and explicitly take a position and distinguish themselves clearly from monistic-spiritual approaches. Such approaches as the one described in the following article, that take these considerations into account could therefore be called neo-integral approaches.

2. Integral Modelling of Leadership and Organizational Development

Integral modelling can be described first as a structured process of creating models at a meta-theoretical level. This process is characterized by some premises and principles which are shortly discussed below. The premises include the theories in the model that do not simply state contradictory statements about a research topic, which require the researcher’s opinion and decision with regard to the content. Instead a complementary relation, which is partially also characterized by paradoxes and emergent phenomena, is recognized in the respective contributions of each individual theory.

From this basic attitude of integral modelling their principles are derived. First, one starts with a reduction to as little fundamentally relevant dimensions and entities of the considered theories as possible, which shall then be represented in a structured diagram. The evolution from theory construction to research subject shall be portrayed through a process of pattern recognition and context formation, thus creating an integrated model. Thereby, the change of research-dominant views on the world and humanity is explicitly taken into account in cross-paradigmatic manner. The meta-theoretical integral modelling that can relate to different research fields is mostly subdivided into three or four key perspectives of a research subject in the sense of individual and collective as well as tangible and intangible elements whose overall context is described as a holon. Depending on the terminology of the integral heuristic, e.g. person system (individual intangible), material-technological environment (collective tangible), social and culture system (collective intangible) and behaviour system[3] (individual tangible), these variables are differentiated. Thus, the evolutionary consideration is already included in an inherent manner in the developmental perspective in such simple systematizations. The adoption of development in the best case to an increasing holonistic complexity arises also from the research-related evolutionary premise of integral modelling and will be considered furthermore in later deductions from the model. Due to such modelling, framework models that have been rather summary or mono-perspective so far can be analysed more comprehensively through leadership theories.

An integral a meta-modelling thus goes beyond current order systems for leadership theories as presented, for example by Avolio et al. but includes their results in a systematic manner. Also Avolio et al. (2009, p. 422) assume an “evolutionary path of theory construction” in their integrative representations. Day and Harrison illustrate this evolution (2007, p. 361) on the basis of an assumed development of leadership theories towards increased complexity and integration. The development of leadership theories began first with simple leadership theories oriented at the leader’s personality and led from leadership dyads consisting of leader and member in the LMX theories to an increased consideration of context conditions as expressed in shared, connective and collective-oriented leadership theories[4]. If one adds the economical perspective of personnel management – which considers above all impersonal contexts of the management of operational target values – to these contributions taken from psychological, sociological and social-psychological research, then, given a maximum abstraction, one can recognize three variables of leadership theory construction which are no longer reducible. They reflect the entities described in the integral model (Deeg et al., 2010) but are already described in a similar way in the framework model by McGrath (1981) regarding stress and behaviour in organizations. After a period of relative neglect, which may also be caused by the fact that McGrath did not understand his framework model as a meta-theoretical one and could not finish the studies of theory constructions, this model has been recently reconsidered in economic-related psychological research (Belschak, 2002; Nellen & Stratmann, 2010).

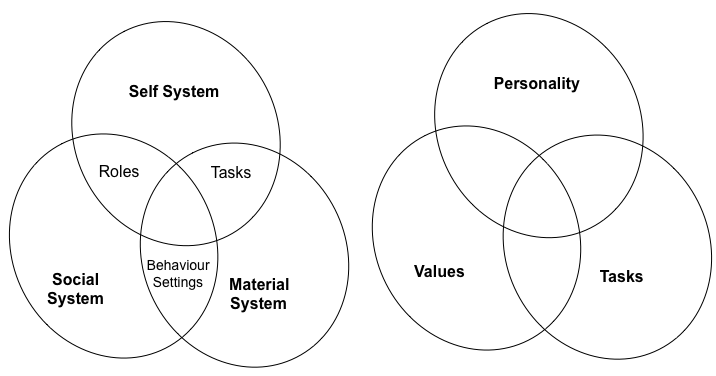

According to McGrath (1981) behaviour in organizations can be deduced from the interaction of three systems. These are circumscribed and defined by the intersection of the two environmental systems, i.e. the material-technological system, which includes primarily physical requirement variables and structure conditions, and the social-personal system as well as the person system of the organization member, i.e. the characteristics of the person. Also Weinert (2004, p. 459) establishes a framework model with three overlapping circles and special reference to leadership. Here leadership (behaviour) is similarly described as a function from three components. Here the interactions between leadership personality, aggregated value conception of the members and situation characteristics in particular for the task are in the centre of the considerations.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of Stress and B ehavior (McGrath 1981) As Compared to Interactions in the Leadership Process (Weinert, 2004)

It is common to both models that they judge interactions and intersection areas as central to describe the phenomenon “leadership”. Thus, they approximate integral conceptions that are expressed with the term “inter-relationality”. It is problematic that both models do represent these intersections graphically but are not able to fill them with content conclusively. For this please see the critique by Semmer (1984), in particular, regarding the lacking operationalization of the intersections in the framework model for stress and behaviour in organizations. During the following multi-theoretical considerations the attempt is made to fill these circles and intersections conclusively and consequently to make it accessible to empirical research. First of all, it shall only be mentioned that framework models for leadership constantly construct similar to equal entities often are without a multi-perspective consistent structure formation. A current framework model of condition factors for a health-favourable leadership (Wilde et al., 2009), for example, fills the suggested system circles with “personal attitudes”, “culture of health-favourable leadership” and “operational resources and possibilities” and the intersection segments with “noticed influences on the co-worker” and “personal competences” when handling this task.

At the meta-theoretical level there is, therefore, an initially sufficient modelling with the three circles because it cannot be reduced furthermore but is explained by existing theories. Based on these integral model-related considerations, with Deeg et al. (2010, p. 195) integral leadership can be understood as:

“intentional, socially accepted influence of these entities and spheres of the organization, its interrelations as well as the organization holon in its whole.”

In a meta-theoretical sense “leader” (in German: “Führungskraft” means leader and a force that leads) is then understood personally as a decisive factor from and on the entities of the leadership holon. The development of leaders is in this sense also the development of person system, social system and structure system. Thus, leadership is positioned in a comprehensive development context which connects it at the same time with organizational development inseparably. Like Volckman (2010) we therefore argue that leadership development is thus also always organizational development and organizational development is always leadership development.

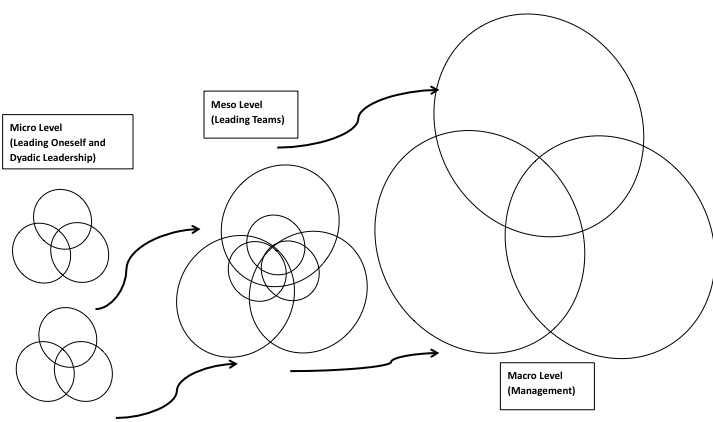

A multi-theoretical analysis separates from the high abstraction level of the meta-theoretical analysis and turns no longer only to abstract and possibly aggregated entities. The subjects of research are no longer the internal logics and supplementing explanation areas of leadership theories. On the contrary, such an approach shall attempt to contribute to a more complex and integrated as well as empirical leadership research based on the exemplary structured basic structure of the leadership whole. The subject of such theory formation therefore is on the object level. With the distinction of these two views on a research subject (meta/multi) category errors made in earlier framework models are avoided. At the same time the structured and multi-perspective overview is maintained by referring to an earlier meta-theoretical integral modelling. However, a number of definitional and model-theoretical differences arise from such an analysis. If from a meta-theoretical analysis the fundamental perspectives are focused on a research subject, then a multi-theoretical analysis consults empirically understandable variables for the content determination of the three system circles. While from a meta-theoretical analysis a holon always is the synopsis of all the entities referred to one another whose development form a single holarchy[5], in the multi-theoretical analysis of a specific subject a holon can always only be an individual, because only the individual has a conscience and not the social construction represented by an organization. Thus, here only individual and no longer reducible variables are considered. The person system is therefore an individual person system. Social system and structure entity thus become in this analysis subjective variables of an environmental perception of the individual. Thus it is illustrated as already described by McGrath as situation. Different from the definition by Deeg et al. integral leadership can therefore from a multi-perspective analysis following Becker (2009, p. 305) and with reference to the framework systems represented in fig. 1 rather be defined in a broader sense as person-, social- and/or material-caused targeted action initiation, which is at the same time retroactive for these spheres[6]. In addition, “development”, which is understood as a single simultaneous emergent phenomenon in interrelated entities in the meta-theoretical analysis, is split in a multi-theoretical analysis of leadership into a holarchic development of the individual’s self and world view and a hierarchical view on different aggregation levels relevant for the organization. Leadership can be understood and regarded on different aggregation levels as autonomous leadership, dyadic direct leader relationship between leaders and member, team leadership at the meso level and finally control at the macro level of the organization as is stressed in personnel management.

Figure 2: Aggregate Levels of Leadership

The abstraction level of a meta-theoretical analysis is thus ultimately developed through the synopsis of the two variables individual development and aggregation (see fig. 2). As part of the recent approaches to multi-level analysis methods in organizational research this problem has already been described sufficiently (Yammarino & Dansereau, 2009). Already Hox and Kreft (1994, p. 283) say that this is a

“major philosophical debate as to whether contexts have any autonomous existence or whether their properties can be fully reduced to the properties of the individuals defining the context.”

They conclude:

“This debate has not led to a firm conclusion.”

Bradbury and Bergman Lichtenstein (2000, p.552) however later come to the conclusion that this objection could be overcome, in that:

“theories about the interdependence of self and society have developed in which neither a positivist nor a constructivist position is stressed. These theories have generated a large body of organizational research that emphasizes the sense-making activity of organizational members.”

From an integral perspective the contradiction described by Hox and Kreft can therefore be resolved with the help of consistent assumptions taken from psychological theories for adult development in which later development stages lead to an increasing construct conscience and self-transcendence in the sense of a unitive movement to a holonic self-conception (Cook-Greuter 2006, p. 163).

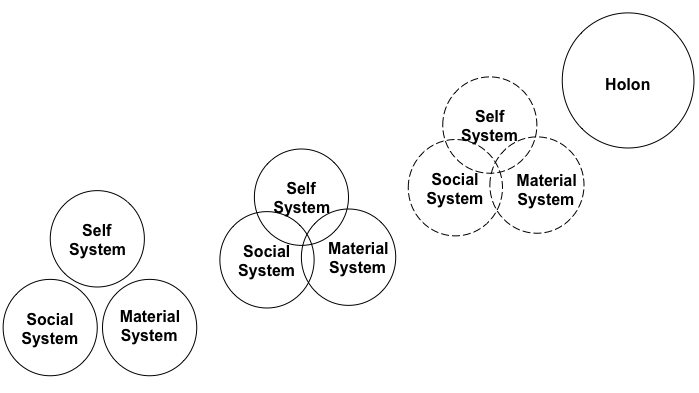

Figure 3: Development from a Multitheoretical and Integral Perspective

In this sense (see fig. 3) the development of the individual holons can also be seen as a development over several stages that first lead to a conscious and complex view of the externalized environmental systems and, through the increasing awareness of interactions and mutual conditionality, eventually to a new super-conscious fusion beyond personal separation. Thus, target variables for a gradual transformation self- and member leadership can be deducted theoretically and specified normatively, which shall be described in the framework of a short discussion of central psychological theories for adult development.

3. The Development Dimension of Integral Leadership and Organizational Development

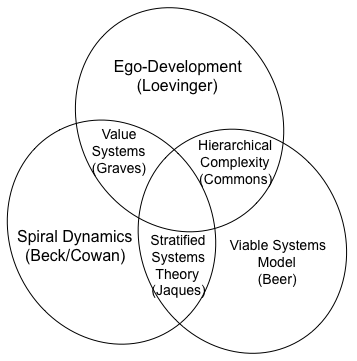

The development idea on which a holarchy is based shall be discussed also due to considerations made above in an integral approach in accordance with relevant and mainly psychological development models for late adult development. The access to the last-mentioned research is best made where an integral approach of existing and well-established theories can be used by incorporating them in its existing systematization. At this point at the level of multi-theoretical analysis, relationships between the content-related statements of the considered theories can be examined. Thus a focus of current integral theory construction is to connect the system circles of an integral framework model indicated above with the idea of development of the relevant developmental theories of the self, values and cognition. Moreover, constructivist hierarchical adult development theories with a wide range of meaning are used, as described by Piaget (1954), for cognitive development to adulthood, by Graves (1974) (Value systems) for further development, by Beck & Cowan (2007) (Spiral Dynamics) for the development of social and value systems in individuals and in societies, by Kohlberg (1984) for the development of moral judgment, Kegan (1986) (Self Identity) and by Loevinger (1976, 1993) (Ego-Development) for the development of the self and by Commons (2008) (General Stage Model of hierarchical complexity) for the hierarchical complexity of tasks and task performance. B But also for contextual conditions, such as the complexity of working conditions, there have been developed hierarchical theories of development. Examples are the Viable Systems Model (VSM) by Beer (1995) and the Stratified Systems Theory (SST) by Jaques (1998).

Beginning with Piaget especially, constructivist development psychology has contributed to answering the question of hierarchically structured differences in increasingly complex entities, such as the individual. It assumes that each individual develops by qualitatively distinguishable stages or waves of the self and world-view and an increasing complexity of the ability for interaction. A fundamental assumption is that human nature adapts dynamically and can develop individually and historically from an evolutionary point of view. In this context the interpretation of experiences is regarded as a genuine human activity. Human beings experience, organize, evaluate and synthesize perceived contents of internal and external sources in order to form and maintain relationships and basic everyday life theories. The specific contribution of development-related psychological theories is to represent the different kinds and ways humans come to such interpretations on the basis of the core themes and development stages offered in the respective theories. In the different theories can be found different starting points for such a categorization. Comparisons between different theories of adult development were quite often made. For such a comparison please see King et al. (1989) who offer a good overview as well as Manners and Durkin (2001) and Dawson (2002, 2003) for newer releases. All of them report a high level of model-theoretical and empirical correspondence. This correspondence may be partly due to the fact that some of the current dominant theories regarding adult development come from the same university, i.e. Harvard[7]. Another reason, however, can also be found in the fact that these theories have all a broad explanatory potential for the same entity. Overall, the analysis and comparison of different constructs at the object level still remain questionable. Still in 2002 (p. 152) Dawson concludes:

“In summary, we presently have a theoretical construct, developmental stage, which has universal properties, in that aspects of the construct are defined similarly across domains, but we have a separate ruler for every domain in which stage is assessed and no satisfactory means for comparing rulers across domains.”

The framework model stated here offers the possibility to maintain the theoretical independence of the analysed approaches and, at the same time, to distinguish them in a common context of justification and locate them accordingly.

First, however, some fundamental development-related psychological theories are represented briefly. The following criteria are taken for the theories:

– The theory should permit an explicit statement about adult development which is also relevant for leadership.

– The theory should contain an assumption about a gradual or wave-based development.

– The theory should have a broad explanatory potential.

– The theory should have the highest possible acceptance in the scientific discourse and include a variety of empirical studies as well as practical and relevant examples.

The last point made it necessary that there also were appropriate methods and procedures to analyse the research object.

Due to these criteria, the theories by Loevinger, Commons and Graves were chosen. A short description of these theories shall be made now in order to locate those theories in the framework model.

3.1 Value-Oriented Theories of Adult Development

As the Spiral Dynamics integral (SDi) framework might be best known in integral circles we will keep the description of this theory quite short. At least we point out that Graves as well as Beck and Cowan in their analysis of the value systems put the value dimension in the centre of their theory. One can speak of a value system even if values are meaningfully connected in a hierarchical relationship (Weibler, 2008, p. 20). Besides the cognitive aspect, these results of construction have above all an emotional and motivational facet and social dimension.

They “help their individuals to move within a community due to their social characteristics, although this community gives each individual proven support to live and satisfy needs through its own value system“(Weibler, there, p. 18).

Or as Hamilton (2012) describes it:

Thus the developmentalists chart the map of potential human (and leadership) growth, while Graves and Beck, in particular, point to the contexting of this within an understanding of complex adaptive [social][8] systems.

The organization culture can therefore be understood as an expression of lived values. Especially the charismatic or transformational leadership uses values in their change efforts in order to influence the organizational culture. (Bass, 1999).

In particular, in academic circles in German-speaking countries there are opinions opposing the formulation of hierarchic value systems, which is probably due to historical reasons. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand that theories with value typology are preferred. Probably due to this reason Schwartz’ universalistic value circle is in the centre of current values research (Schwartz, 2006). However, Schwarz himself has repeatedly pointed out that his theory is based on a value hierarchy both at an individual and an aggregated level of social constructs as represented by organisations and nations (2001, p 24). Furthermore Strack (2011, p p . 22) proves in her empirical study that Grave’s value system and the value circle according to Schwartz are based on the same value structure.

A problem in the recognition of a hierarchical development of value systems is that they are not present at the individual level in a pure form, i.e., it is assumed that for each individual values of a previous stage of development are/can be of high importance according to the respective learning history and situation. Therefore, a development always takes place as an interlacing and individual collection of value preferences from different value systems that make access to new values and, at the same time, maintains old ones. Therefore, value systems have a clear holarchic order. Individual value preferences form, however only conditionally and if so, only over the long term. Moreover, problems arise when measuring such value systems, especially with regard to answer tendencies and distortions due to social expectations. This is especially true because the common methods used are highly transparent. Thus Karsten (2006) comes to the conclusion in her empirical study that the available procedures “Form A” and “Value test” have doubtful to insufficient internal consistencies and the test persons partially had difficulties to understand the wording of the questionnaire. In “Second Tier Perspective Meme Analyzer” Willkommen (2008) defines another method of acquiring value systems that is based on Grave’s Values System. Also this method is, however, characterized by a high transparency and has not been validated except for a first expert survey.

Caspers et al. (2011) present a neuro-psychological economy-related study in which the dimensions of the Value Systems could be confirmed only partially, but a distortion-free method could be developed and applied that has a high correlation with the Values Test. Further publications about this research in which the author participated are in preparation.

3.2 Self-Identity and/or Ego Development as Focus of Adult Development

In contrast to the Value systems the studies about “ego development” (Loevinger) and “self-identity” (Kegan) have a long and broad academic tradition. At this point, only the “ego development” construct shall be discussed for which now more than 400 empirical studies are available. Westenberger et al. (1998) describe the concept of the “ego development” as a strictly empirically acquired description of qualitative developments of personal growth and thus as one of the most important achievements of personality and development psychology. Even the “Washington University Sentence Completion Test” (WUSC) is a valid method for a projective and thus distortion-free measurement of the theoretically postulated stages (Manners & Durkin, 2001) for which also modified methods with integral focus (SCTi-MAP, Cook Greuter) and methods applicable to the business context method (LDP, Torbert and I-E-Profil, Binder) are available. There are empirical studies for different leadership-relevant contents. Most relevant studies deal with organization consulting and leadership coaching (Carlozzi et al., 1983; Borders et al., 1986; Borders and Fong, 1989; Shrubs and Gibbs, 1990; MacAuliffe and Lovell, 2006). For a leadership context in a strict sense, Smith (1980) shows a more balanced employment of power and control during conflicts. Merron (1985) reports a better decision-making process of managers with high ego development under uncertain conditions. Quinn and Torbert (1987) confirm a more competent handling with feedback. Corbett (1995) reports a larger competence for learning from experience. Rooke and Torbert (1998) can associate the increasing capacity of decision-makers and company owners to successfully conclude organization transformation projects with the height of the ego-development level. Cooper (2005) reports similar results from a study conducted in the public administration of Australia. Brown (2012) presents a respective study for managers and change agents in sustainability projects.

Loevinger (1976) describes her construct as the specific pattern with which a person perceives and interprets one’s self and the world. This ego structure develops by repeated transformations in qualitative and basically irreversible jumps to an increasing and thus more comprehensive and more integrated awareness. Here the “ego” is a fundamental organizing principle of thoughts and experiences of an individual. This organizing principle shows a high temporal stability, but can also further develop gradually under certain conditions (development conflicts and confusions) in adults in the context of the universal logic described by the postulated stages. Following Sullivan (1953) Loevinger defines “ego development” as a fear-repelling principle by which experiences contradicting one’s own self-concept are filtered. Depending on the situation, short-term regression as a reaction to prior action logics is possible under stress. Based on this idea, a connection to current neuro-psychological dual process theories can be seen[9].

All in all, the stable formation of the process of meaning-making especially in internal processes within a stage is in the centre of the “ego development” construct. However, this also always means giving a meaning to the environment, i.e., everything that does not belong to or is fended off by the “ego”. This results in stage-specific action logics of a person. By comparing the partially significantly different meanings given by many test participants, Loevinger and others have been able to illustrate until today nine different stages of “ego development” in extensive empirical studies. Each of these stages is a typical form for the psychic organization of thoughts and experiences. The organizing principles of a stage can be understood and evaluated as directed downwards also in other interpretations. Understanding development stages that one has not reached yet is however not possible, so that people in contact with individuals of a later development stage can anticipate the behaviour of those individuals only according to their own stage and might often misinterpret it. The substantial characteristics of the eight ego development stages which can be measured in adults are described briefly below:

– One’s own advantage stands out at the self-protective opportunistic stage. Employees, colleagues and superiors are used as far as possible as means to satisfy one’s specific needs. Other persons do not have intrinsic values. Behaviour is throughout opportunistic. This means in a working context that actions are characterized by routine. These employees find it difficult to give and receive feedback. In the case of failure, one tries to find external accusations.

– Thinking and acting at the community-determined conformist stage is oriented towards standards and regulations. Furthermore, one tries to adapt to those peer groups that are considered important. Being part of such a group forms the identity and subordination is considered mandatory. For this reason behaviour is mainly characterized by avoiding conflicts. There is always only a right or a wrong solution.

– At the rationalist expert stage there already is an orientation towards internalized standards. Causal explanation patterns determine thinking. The efforts to distinguish oneself from others and to push one’s own ideas through have priority, especially with regard to how work processes shall run and results shall be obtained. Efficiency and effectiveness have a high meaning within the context of one’s own professional expertise.

– A strong goal orientation prevails at the autonomous success-oriented stage. The individual strives for self-optimization within the context of autonomous values, conceptions and goals. At this stage the employee or superior can handle complex work tasks. A rich experience and descriptions of one’s inner life are also possible. Those opposition are regarded as equal and exchange is characterized by respect for individual differences.

– The pluralistic relativizing stage makes it possible for the employee and/or manager to have a first idea about how their own perceptions influence their views on the environment. One’s own ideas and conceptions of the world are increasingly analysed. Internal and external conflicts can now be accepted more and tensions can be borne.

– The strategic-autonomous stage gives a fully developed multi-perspective view on the self and the environment. The employee and/or manager are able to integrate contradictory opinions. Work tasks are understood as processes while maintaining a goal orientation. Reciprocal actions can be understood in a systemic manner. At this stage the individual is highly motivated to develop further. At the centre of this development, however, are less specific work tasks, but an addressing of fundamental conflicts that require high tolerance and acceptance of ambiguity and high respect for the autonomy of others and reconciliation with one’s own negative characteristics.

– At the integrated construct-conscious stage, individuals can integrate paradoxes. Experiences are always re-evaluated and associated flexibly with other contexts. At the same time, there is a high awareness of one’s own currently prevailing attention focus and state of consciousness.

– At the flowing unitarian stage the need to evaluate other is not existent. This rarely reached stage is characterized by a merging with the world and a letting go of reality- and self-constructions uphelt. Characteristic of this flow state is a playful attitude with rapid changes between the serious and the trivial and a mesh of different states of consciousness. Thought has a long time horizon and is based on historical contexts.

3.3 Cognitive-Oriented Theories of Adult Development

Cognitive-oriented theories of adult development have their origin in the basic research of Piaget. Since the postulated development stages end with the beginning of adulthood, an equally oriented cognitive theory shall be presented which is based on the stages postulated by Piaget, but continues into adulthood. Commons often refers to Piaget, occasionally calls himself neo-Piagetian (Commons & Richards, 2002, p. 159) and points out that he has differentiated Piaget’s stages and continued into adulthood well beyond formal operations[10]. This postulate has led to a lively debate within developmental psychology as to whether the stages formulated by Commons are merely refinements of the formal operational stages according to Piaget. This discourse seems to be momentarily in favour of the model-theoretical differentiation made by Commons.

While the two approaches outlined above have values and meaning in the centre of their observations, the strongly analytic and logical-mathematical theory of hierarchical complexity by Commons (2008) focuses on structural aspects of higher cognition achievements and mental operations. In the context of this theory logical degrees of operations of increasing complexity represent the crucial criterion of derived formal and post-formal development stages in adulthood. Clearly defined and hierarchically arranged problems and tasks of increasing level of difficulty must be met with increasingly more complex and more abstract logical-deductive thinking in order to find an adequate solution. Procedures to ascertain these stages mostly involve so called balance beam problems where correct solutions are found through logic-mathematical operations of increasing levels of difficulty for which weights must be found to balance a beam (Commons et al., 1995). Instead of “values” or the “ego” cognition and abstract thinking is in the centre of these analyses. Here, individuals are located at the highest level at which they can manage specific tasks cognitively with success. This quantitative approach has its strengths in a high precision and stringent systematization and heuristic for the stage construction. This theory and the stages derived can be marked as maximally loadable. However, the comprehensive requirement for validity of the theory to be a generalized theory of adult development has been rightly rejected in many cases (Cook-Greuter, 1999, p. 72).

There are also numerous empirical studies for the theory of hierarchic complexity. Commons et al. for example relate explicitly to the organization and the leadership context with a study on the influence of organizational culture (1993), Armon (1993) with a study on good workplace practices, Bowman (1996) with a study on workplace organization, Oliver (2004) with a study on leadership and after crises and Commons et al. (2006) with a study on cross-cultural leadership.

The 14 stages of the theory begin before the development stages described by Piaget. Due to the focus on adult development, only the stages starting from stage 7 shall be described here briefly:

– The senso-motoric stage is characterized by the ability to tell stories, make simple deductions and count to 5.

– The primary stage is characterized by the ability for simple arithmetic operations like in the 4 arithmetic basic operations.

– The concrete-operational stage is characterized by a complete and complex arithmetic that enables individuals to put themselves in someone’s position rudimentarily and follow social rules.

– The abstract stage is characterized by the ability to form abstract terms and variables from finite classes of specific phenomena. This enables the individual to make logical quantification and categorical statements.

– The formal-operational stage is described by the ability of the individual to coordinate two abstract variables in mind and calculate the influence of one variable on the other.

– The system(at)ic level is achieved when the individual is able to form multiple relationships between abstract variables, which is equivalent to the formation of a system according to Commons.

– The meta-system(at)ic stage involves the comparison and coordination of different systems and thus the formation of meta-systems and theories in terms of theories about theories.

– The paradigmatic stage is reached if such meta-systems are coordinated and integrated successfully in fields of knowledge.

– The cross-paradigmatic stage is reached when paradigms are coordinated in such a way that new fields of knowledge consisting of several paradigms are formed.

3.4. Multi-Theoretical Overall View and Classification

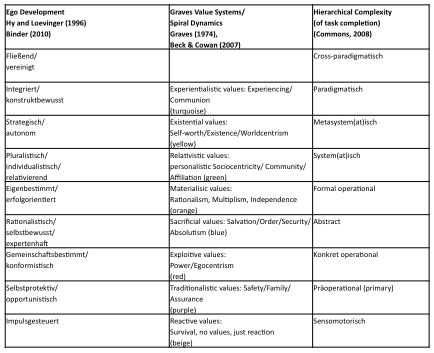

A comparison of the three theories described above for adult development will now be made in a table.

Table 1: Comparison of Different Theories of Adult Development

Many similarities in the central content of the stages, including the number and sequence of the stages expected theoretically for adult development, can be found in the different models -theoretical basic assumptions and approaches as well as different and independent constructs. However, the model-theoretical correspondence should not be confounded with a constant existing and in any way mandatory parallel development status of the stages in an individual. Here must – amongst others according to Cook-Greuter (2006, p 160) – be expected different levels of development in the different development paths, which can be deducted only in part from the learning-related specific stimulating or challenging context conditions.

With the remarks just made, the theories described can be located in the integral 3-circle model (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Localisation of Developmental Theories in a New-Integral Framework

Analogous to Kohlberg (Colby & Kohlberg, 1987, cited in Dawson, 2003, p. 345) and confirmed by Walker’s (1980, p. 137) empirical study, this article is for a separate but related consideration of the three theories.

Kohlberg, along with other proponents of domain theory, argued that development in different knowledge domains involves fundamentally different processes. For Kohlberg, the moral [and value][11] domain constitutes a unique structure parallel to, but progressively differentiated from, both the Piagetian logic-mathematical domain and the perspective-taking domain [of ego-development] … He argued that perspective-taking development involves capacities in addition to basic cognitive capacities. Cognitive development regards the objective environment, whereas perspective-taking involves comprehension of how people think… moral [and value systems] development demands an additional step – knowledge of how people should think and act toward one another.

It can also be assumed that individuals are able to activate differentially these various domain-relevant (sub-)systems of values, self- and cognitive development due to primary evaluation processes according to a subjective assessment of the predominant nature of the requirements of the context conditions. Comparable to the stress-theoretical assumptions of a differentiable primary and secondary appraisal (Lazarus & Launier, 1981), different assessments would then initiate different action-preparing decisions with a focus on coping. Leadership could therefore also be understood as a coping-oriented three-stage cognitive and schema-guided process of the primary assessment (detection of the relevant co-response subsystem) and the secondary assessment (goal setting) whose third stage is the preparation of action[12]. From the different activation together with the different development level in each corresponding sub-system of the theory can be expected a more or less pronounced adaptation to context and are more or less high degrees of complexity of acquisition, goal setting and choice of behaviour. This may be misinterpreted by other persons because of their preferred and maybe different choice of subsystem to be activated and probably due to the development stage different from this subsystem. Also the assumption of a consistency at the level of development of the different subsystems of an interaction partner may be disappointing quite often during repeated and concrete mutual exchanges and encounters at the workplace. Inauthentic leadership must be located therefore not alone for managers but is also established in these conditions for different attribution and evaluation processes of the partners involved. If one considers the great importance of “trust” within psychological theories (see first condition variable of Sense of Coherence SOC according to Antonovsky, 1997), but also newer leadership theories, such as the transformational and authentic leadership, the meaning and contribution of an integral leadership modelling at a specific multi-theoretical level becomes clear. After the misinterpretation by the interaction partner follows most likely an inadequate activation of an own subsystem. Leadership and organizational behaviour is therefore in this sense a mutual attribution and negotiation process with many cliffs and obstacles. Target of integral leadership would thus be to make more conscious and therefore potentially also more congruent decisions in order to be understood better in a mutual transformational process. Authentic and transformational leadership would then be understood as an inter-relational and integrative practice that, from an integrally informed self-management and development of partial selves, answers the requests from the organization holon. Future “leadership skills” would then be less based in expertise and more in the highly (ego) developed ability to tolerate ambiguity, to think in a multiple and crosswise way, to perceive one’s own internal states and the different patterns of various developmental parameters in the organization holon and to give developmental feedback.

4. Prospects

By far, not all model-theoretical aspects and extensions of an integral modelling could be discussed and analysed in this article. For example, little or nothing was said about the integration of neuro-psycho-economic research and the implications of a consideration and model integration, in particular, of the meaning of intuition in the dual process theory (Kahneman, 2003) as well as the consideration of the research on emotional intelligence, personality theories (Furnham, 1996) and states of consciousness (Belschner, 2004). First results of the field are already available in the publication mentioned before regarding interdisciplinary research projects by Caspers et al. (2012) in which the author was involved. Further contributions for this are in preparation. The parallels to the Constructive Developmental Framework of Laske (2010), could also not be discussed.

However, some evidence of both meta-theoretical approaches as well as empirical research from a multi-theoretical perspective on neo-integral approach is given. In particular for the last-mentioned approach there could be raised numerous research questions for which, however, no answer can be given, because the respective tools are not yet available. However, with the WI-SE test-system[13] the author provides online-secured tests open for research based on previous multi-theoretical integral analyses, which contains the system circles and intersections and also includes further relevant variables and, upon conclusion of the preliminary tests, promises such an integral and integrated empirical access as indicated in this article.

This article is a slightly modified and translated version of an article originally published in the special edition of “Wirtschaftspsychologie” on “Neo-Integral Leadership”. “Wirtschaftspsychologie” is the leading academic journal on economic psychology in the German speaking countries with several thousands of subscribers in universities and HR departments of leading organisations.

This article is a slightly modified and translated version of an article originally published in the special edition of “Wirtschaftspsychologie” on “Neo-Integral Leadership”. “Wirtschaftspsychologie” is the leading academic journal on economic psychology in the German speaking countries with several thousands of subscribers in universities and HR departments of leading organisations.

The author wants to thank Russ Volckmann for the thoughtful and well-informed edits and interesting dialogue.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1997): Salutogenese: Zur Entmystifizierung der Gesundheit. Dgvt-Verlag, Tübingen

Armon, C. (1993): The nature of good work: A longitudinal study. In: Demick, J. & Miller, P.M. (Eds.): Development in the workplace (pp. 21-38). Hillsdale, Erlbaum

Avolio, B. J.; Walumbwa, F. O. & Weber, T. J. (2009): Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions. In: Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421-449

Bass, B. M. (1999): Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8 (1), 9-32

Beck, D. & Cowan C. (2007): Spiral Dynamics – Leadership, Werte und Wandel: Eine Landkarte für das Business, Politik und Gesellschaft im 21. Jahrhundert. Kamphausen, Bielefeld

Becker, M. (2009): Personalentwicklung: Bildung, Förderung und Organisationsentwicklung in Theorie und Praxis, 5. aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage, Stuttgart

Beer, S. (1995): Diagnosing the System of Organizations. Chichester: Wiley

Belschak, F. (2002): Stress in Organisationen. Pabst Science Publishers, Lengerich

Belschner, W. (2004): Consciousness Mainstreaming – Eine dringende Strategie der Bewusstseinsbildung und einer Bewusstseinskultur. In: Psychologie des Bewusstseins, 122-152

Benedikter, R. & Molz, M. (2011): The rise of neo-integrative worldviews – Towards a rational spirituality for the coming planetary civilization? In: Hartwig, M. & Morgan, J. (Eds.): Critical Realism and Spirituality, Routledge

Borders, L.D.; Fong, M.L.; Neimeyer, G.J. (1986): Counseling students’ level of ego development and perceptions of clients. In: Counselor Education and Supervision, 26, 36-49

Borders, L.D. & Fong, M.L. (1989): Ego development and counseling ability during training. In: Counselor Education and Supervision, 29, 71-83

Bowman, A.K. (1996): The relationship between organizational work practices and employee performance: Through the lens of adult development. Unpublished Dissertation, Fielding Institute

Bradbury, H. & Bergman-Lichtenstein, B. M. (2000): Relationality in Organizational Research: Exploring the Space Between. In: Organizational Science, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp.551-564

Brown, B. C. (2012): Leading complex change with post-conventional consciousness. In: Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25 (4), 560-577

Bushe, C.R. & Gibbs, B.W. (1990): Predicting organization development consulting competence from the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and stage of ego development. In: Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 26 (3), 337-357

Carlozzi, A. F., Gaa, J.P.; Liebermann, D.B. (1983): Empathy and ego-development. In: Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 113-116

Caspers, S.; Heim, S.; Lucas, M.; Stephan, E.; Fischer, L.; Amunts, K. & Zilles, K. (2011): Moral Concepts Set Decision Strategies to Abstract Values. In: PLOSone, 6 (4), online: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0018451

Caspers S, Heim S, Lucas M, Stephan E, Fischer L, Amunts K & Zilles K. (2012): Dissociated neural processing for decisions in managers and non-managers. In: PLoSOne, 7 (8): e43537.

Commons, M.L. (2008): Introduction to the Model of Hierarchical Complexity and its Relationship to postformal Action. In: World Futures, 64, 305-320

Commons, M.L.; Krause, S.R.; Fayer, G.A. & Meaney, M. (1993): Atmosphere and stage development in the workplace. In: Demick, J. & Miller, P.M. (Eds.): Development in the workplace (pp. 199-220).Hillsdale, Lawrence Erlbaum

Commons, M.L.; Goodheart, E. & Bresette, L.M. (1995): Formal, systematic, and metasystematic operations with a balance-beam task series: A reply to Kallio’s claim of no distinct systematic stage. In: Adult Development, 2 (3), 193-199

Commons, M.L.; Trudeau, E.J.; Stein, S.A.; Richards, F.A. & Krause, S. R. (1998): Hierarchical Complexity of Tasks Shows the Existence of Developmental Stages. In: Developmental Review, 18, 237-278

Commons, M.L. & Richards, F.A. (2002): Organizing Components into Combinations: How Stage Transition Works. In: Journal of Adult Development, 9 (3), 159-177

Commons, M.L.; Galaz-Fontes, J.F. & Morse, S.J. (2006): Leadership, cross-cultural contact, socio-economic status, and formal operational reasoning about moral dilemmas among Mexican non-literate adults and high school students. In: Journal of Moral Education, 35 (2), 247-267

Cook-Greuter, S.R. (1999): Postautonomous Ego Development: A Study of Its Nature and Measurement: Unpublished Dissertation, Harvard University

Cook-Greuter, S.R. (2006): 20th Century Background for Integral Psychology. In: Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, Vol. 1, No.2, 144-184

Cooper, P. (2005): Developing transformational leadership capacity in the public service. In: Public Administration Today, 3, 66-76

Corbett, R.P. (1995): Managerial style as a function of adult development stage. Unpublished Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Dawson, T. L. (2002): A Comparison of Three Developmental Stage Scoring Systems. In: Journal of Applied Measurement, 3 (2), 146-189

Dawson, T. L. (2003): A Stage is a Stage is a Stage: A Direct Comparison of Two Scoring Systems. In: The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 164 (3), 335-364

Deeg, J.; Küpers, W.; Weibler, J. (2010): Integrale Steuerung von Organisationen. Oldenbourg Verlag, München

Edwards, M. (2008): Where’s the Method to Our Integral Madness? An Outline of an Integral Meta-Studies. In: Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 165-194

Esbjörn-Hargens, S. (2006): Integral Research: A Multi-Method Approach to Investigating Phenomena. In: Constructivism in the Human Sciences, Vol. 11, 1, 79-107

Furnham, A. (1996): The big five versus the big four: the relationship between the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and NEO-PI five factor model of personality. In: Personality and Individual Differences, 21 (2), 303-307

Grätsch, S. (2010): Das Graves-Value-System – oder: Wie können Werte im Unternehmen gemessen und aktiv gestaltet werden? In: Wissenswert, 3, 16-23

Graves, C. W. (1974): Human Nature Prepares for a Momentous Leap. In: The Futurist, April, pp. 72-87

Hamilton, M. (2012): Leadership to the power of 8: Leading self, others, organization, system and supra-system. In: Wirtschaftspsychologie, 3, pp. 58-64.

Hernandez, M.; Eberly, M. B.; Avolio, B. J. & Johnson, M. D. (2011): The loci and mechanisms of leadership: Exploring a more comprehensive view of leadership theory. In: The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 1165-1185

Hox, J. J. & Kreft, I. G.G. (1994): Multilevel Analysis Methods. In: Sociological Methods & Research, Vol. 22, No. 3, 283-299

Jacques, E. (1998): Requisite Organizations. Arlington: Cason Hall & Co

Johnson, R. B. & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004): Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. In: Educational Researcher, 33 (7), 14-26

Kahnemann, D. (2003): Maps of bounded rationality: A perspective on intuitive judgement and choice. In: American Economic Review, 93 (5), 1449-1475

Karsten, E. (2006): Spiral Dynamics onderzocht – Een studie naar de validering en betrouwbaarheid van vragenlijsten op het gebied van Spiral Dynamics. Unpublished Thesis, University of Amsterdam

Kegan, R. (1986): Die Entwicklungsstufen des Selbst – Fortschritte und Krisen des menschlichen Lebens. München: Peter Kind Verlag

King, P. M.; Kitchener, K. S., Wood, P. K. und Davidson, M. L. (1989): Relationships across developmental domains: A longitudinal study of intellectual, moral and ego development. In Commons, M.L.; Sinnot, J. D.; Richards, F. A. und Armon, C. (Eds.): Adult development. Volume 1: Comparisons and applications of developmental models (pp. 57-71). New York: Praeger

Koestler, A. (1984): Die Wurzeln des Zufalls. Scherz, München 1984

Kohlberg, L. (1984): Essays on moral development. The psychology of moral development. San Francisco: Harper & Row

Laske, O. (2010): Editorial: The Constructive Developmental Framework – Arbeitsfähigkeit und Erwachsenenentwicklung. In: Wirtschaftspsychologie, 1, 3-16

Lazarus, R.S. & Launier, R. (1981): Stressbezogene Transaktion zwischen Person und Umwelt. In: Nitsch, J.R. (Hrsg.): Stress, Bern: Huber

Leithoff, S & Lucas, M. (2011): Zur Gestaltung einer gesunden Organisationsentwicklung – Durch integrale Orientierung gesundheitsförderlich führen und steuern. In: Winterfeld, U./Godehardt, B & Reschner, C.: Die Zukunft der Arbeit, 111-130

Lessem, R. & Schieffer, A. (2009): Transformation Management: Towards the Integral Enterprise. Ashgate Publishing, Farnham

Loevinger, J. (1976): Ego development. Conceptions and theories. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass

Loevinger, J. (1993): Ego development: Questions of method and theory. In: Psychological Inquiry, 4, 56-63

MacAuliffe, G. & Lovell, C. (2006): The influence of counselor epistemology on the helping interview: A qualitative study. In: Journal of Counseling and Development, 84, 308-317

Manners, J. & Durkin, K. (2001): A Critical Review of the Validity of Ego Development Theory and Its Measurement. In: Journal of Personality Assessment, 77 (3), 541-567

McGrath, J. E. (1981): Stress und Verhalten in Organisationen. In Nitsch, J.R. (Hrsg.): Stress: Theorien, Untersuchungen, Maßnahmen, 441-499. Stuttgart: Huber

Merron, K. (1985): The relationship between ego-development and managerial effectiveness under conditions of high uncertainty. Unpublished Dissertation, Harvard University

Merton, R. K. (1998): Soziologische Theorie und soziale Struktur. De Gruyter, Berlin

Meyerhoff, J. & Visser, F. (2010). Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber’s Theory of Everything. Inside the Curtain Press.

Nellen, M. & Stratmann, T. (2010): Wertekongruenz und Arbeitsstress im organisationalen Kontext – ein Strukturgleichungsmodell der vermittelnden psychologischen Faktoren. In: Bungard, W. & Müller, K. (Hrsg.): Mannheimer Beiträge zur Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, Heft 1, 15-24

Niglas, K.; Kaipainen, M. & Kippar, J. (2008): Multi-perspective exploration as a tool for mixed methods research. In: Bergman, M. M. (Ed): Advances in Mixed Methods Research: Theories and Applications. Sage Publications Ltd

Niglas, K. (2010): The Multidimensional Model of Research Methodology: An Integrated Set of Continua. In: Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research (2nd. Ed.), pp. 215-236, Sage, Los Angeles.

Oliver, C.R. (2004): Impact of catastrophe on pivotal national leaders’ vision statements: Correspondences and discrepancies in moral reasoning, explanatory style, and rumination. Unpublished Dissertation, Fielding Institute

Piaget, J. (1954): The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books

Quinn, R. & Torbert, W.R. (1987): Who is an effective transforming leader? Unpublished paper, University of Michigan

Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. R. (1998): Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s developmental stage. In: Organizational Development Journal, 16 (1), 11-28

Rosenstiel, L. v. (2004): Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie – Wo bleibt der Anwendungsbezug? In Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie A&O, Vol. 48, Nr. 2, 87-94

Scharmer, C. O. (2009): Theorie U – Von der Zukunft her führen. Carl-Auer Verlag, Heidelberg

Schwartz, S. H. & Bardi, A. (2001): Value Hierarchies Across Cultures: Taking a Similarities Perspective. In: Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 268-290.

Schwartz, S. H. (2006): Basic Human Values: Theory, Measurement, and Applications. In: Revue francaise de sociologie, 47 (4), 1-43

Semmer, N. (1984): Stressbezogene Tätigkeitsanalyse. Psychologische Untersuchungen zur Analyse von Stress am Arbeitsplatz. Weinheim: Beltz

Shermer, M. (2011): The believing brain. Times Books, New York

Smith, S.E. (1980): Ego development and the problems of power and agreement in organizations. Unpublished Dissertation, Fielding Institute

Strack, M. (2011): Graves Werte-System, der Wertekreis nach Schwartz und das Competing Values Model nach Quinnn sind wohl deckungsgleich. In: Wissenswert, 1, pp. 18-24

Volckmann, R. (2010): Integral Leadership Theory. In: Richard Couto, Ed., Political and Civic Leadership, Volume 1. Los Angeles: Sage, pp.121-127

Walker, L.J. (1980): Cognitive and perspective taking prerequisites for moral development. In: Child Development, 51, 131-139

Weibler, J. (2008): Werthaltungen junger Führungskräfte. Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Düsseldorf

Weinert, A. B. (2004): Organisations- und Personal psychologie, Beltz, Weinheim

Westenberger, P.M.; Blasi, A.; & Cohn, L.D. (1998): Personality development: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical investigations of Loevinger’s conception of ego development. Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associations

Wilber, K. (1996): Eros, Kosmos, Logos – Eine Jahrtausend-Vision. Wolfgang Krüger Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

Wilde, B.; Hinrichs, S., Bahamondes, C. & Schüpbach, H. (2009): Führungskräfte und ihre Verantwortung für die Gesundheit Ihrer Mitarbeiter – Eine empirische Untersuchung zu den Bedingungsfaktoren gesundheitsförderlichen Führens. In: Wirtschaftspsychologie, 2, 74-89

Willkommen, S. (2008): Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Werthaltungen – Eine Anwendung der Delphi-Methode. Unpublished Thesis, University of Oldenburg

Yammarino, F. J. & Dansereau, F. (2009): Multi-Level Issues in Organizational Behavior and Leadership. Emerald, Bingley

Notes

[1] The term holon (from the Greek “whole being”) was coined by Arthur Koestler and means a whole that is part of another whole. It is also described as “whole/part”. For example, a cell is in itself a whole, but part of a larger whole: an organ which is in turn part of the body. Generally speaking, the holon is a system of relations which is represented at the next higher level as a unit i.e. a relatum. Such a hierarchy consisting of holons is called holarchy.

[2] See also Benedikter and Molz (2011, p. 36) and Myerhoff (2010) for a critique of these approaches.

[3] However, Cook Greuter (1999) points out that behaviour is to be differentiated as „a content factor “from the other entities which refer to underlying „structures“. Thus, in this sense behaviour would be only a derived size which leaderships to a reduction to three system circles within the framework of the system to be presented. Behaviour is seen as visible consequence of the decisions made in the centre of the three circles.

[4] Instead of a detailed description of the individual theory contributions only the basic idea of integral modelling shall be further pursued at this point with the goal to justify a basis for the subsequent multi-theoretical analysis. For an integral representation of the individual leadership theories you may also refer to Deeg et al 2010.

[5] Holarchy applies only in the abstract sense and not in the narrow sense of a temporal sequence or an emergence of specific objects.

[6] The focus on decision contained in this definition attempt results from the later research on adult development.

[7] It can be assumed and is partly also proven that these development theories were formulated on the basis of the other approaches and a dialogue with the representatives of the other theories.

[8] The square brackets include an addition made by the author of this article which underlines the specific context of the multi-theoretical framework model but should not distort the statement quoted excessively.

[9] This approach has been analysed in another publication of the neuro-psycho-economic studies of Casper et al Followed (2012) which, however, cannot be further discussed due to further necessary theoretical and practical observations.

[10]For a comparison of the stages by Commons and Piaget see also Commons et al. (1998).

[11] Square brackets are additions made by the author in order to explain model-theoretical assumptions of this article.

[12] For an explanation of this idea please see further studies (Caspers et al., 2012) which suggest an extension of the model-theoretical assumptions made in this article by integrating and considering dual process theories.

[13] www.wei-se.de (German) or www.vvi-se.com (English), further languages will be added.

About the Author

acute trauma response and integrally oriented personal and organizational development. For more than 15 years he has been leading projects in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Turkey, Spain, Denmark and elsewhere. In his research and publications he integrates neurosciences with psychology and economics.

For more information see also: www.lucoco.com

Contact at LUCOCO: marc.lucas@lucoco.de

Contact at University of Hagen: marc.lucas@fernuni-hagen.de