Mark McCaslin and Jason Flora

Mark McCaslin

Jason Flora

There is an important relationship at work concerning integral leadership and the notion of the leader in a teaching and learning role. Integral leadership positions itself at the intersections of potential and therefore seeks the ability to use multiple approaches, multiple lenses, and to fashion the wide-reaching theoretical aims of leadership studies towards addressing existing problems and emergent opportunities. Integral Leadership illuminates the interrelationships occurring within this intersectional space, this transdisciplinary space, thereby inviting the leader to become open to learning in order to transactively achieve the community of practice’s mutual or collective purposes. In addition, Integral leadership sets its intention towards building bridges that will span the distance between the practical, the theoretical, and the personal.

The leader in a teaching and learning role encompasses many of the qualities and utilizes the metagogical practices (practices that engage the learner) of a Potentiator (McCaslin and Scott, 2012). The Potentiator demonstrates a willingness to learn and then, through this willingness, creatively engages that learning towards solving the challenges of the problems being presented and/or rising to meet the emerging opportunities. A Potentiator can best be represented as an attitude, a philosophy, which is made progressively more compelling through reflective or potentiating practice. Due to their openness towards learning, they grant themselves the permission to believe in an integral philosophy of leading and learning without having yet perfected its purpose. Potentiators are creatively self-aware as they hold the practiced skill of critical reflection. Due to their focus on building the potential of others as well as their own, Potentiators hold the realized ability to move in and out of the leader role as the situation dictates. Given that integral leadership purposes itself as a bridging construct, Potentiators, working and creating within what might be called an Integral Space, would be, by definition, be open to learning. Furthermore, given the transdisciplinary, transcultural, and trans-spiritual elements radiating from any Integral Space, an openness to learn gives the Potentiator a greater reach towards resolving conflicts, solving problems, and developing innovative solutions.

The Integral Space

The Integral Space cannot be represented as a physical space, as to do so would immediately arrest its purpose and possibilities. Indeed, we hold a reluctance to pull this space apart even for the purpose of gaining clarity. With all due respect for the integrity of the Integral Space, it is possible to paint this Integral Space philosophically as well as conceptually without necessarily limiting its potential reach and purpose. To begin, the Integral Space would be best understood as a living dynamic existing within a community of practice. For the purposes of this paper a community of practice is defined as the joint enterprise within a collection of human potentials (an organization, school, or community) that creates a sense of accountability and engagement to the collective’s body of knowledge (Dixon, 2000). A community of practice strives to ensure the success of its members (Wenger, 2000). “For a community of practice to flourish, members must have a strong sense of belonging and engage in new learning initiatives to ensure the community’s knowledge does not become stagnant. The negotiation of the meaning of knowledge in a CoP [community of practice] results in members learning and transforming; thus, the current practice, the status quo, needs as much explanation as the need for change” (Carlson, 2003, p. 16). Communities of practice engage in the “generative process of producing their own future” (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 58). Like the Integral Space, a community of practice is a “living repository of community learning, knowledge is created, accumulated, stewarded, and diffused in the organization” (Carlson, 2003, p. 20).

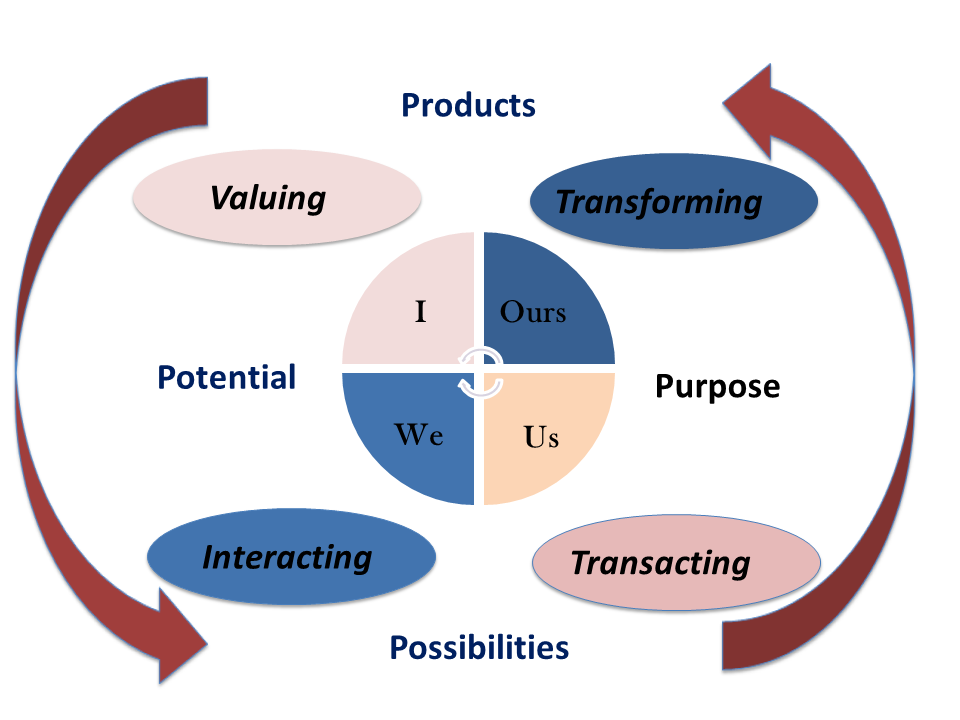

As a result of its living dynamic nature, the Integral Space is truly never at rest but constantly evolving towards a synergistic possibility where emerging problems and/or emerging opportunities are creatively addressed. While it is possible to discuss the various elements at work within the Integral Space, it should be noted that these various elements are, in reality, inseparable. The elements of valuing, interacting, transacting, and transforming are at work together. Even pulling or lifting one element away from the integral flow will collapse the entire dynamic. While there is no true beginning or ending with the dynamic flow happening within the Integral Space we will begin our articulation of these elements with the notion of valuing.

Valuing

The emergent or existing opportunities and/or emergent problems are not evaluated by the Potentiator— they are valued. We are trained, largely through post-modern processes, to deconstruct knowledge and practices. Within the Integral Space this is seen and felt as an act of violence. It is really a matter of approach as in; “How do we approach beauty?” The valuing approach enlivens creativity and deepens our ability to engage in creative discussions. Within this aspect of the dynamic the Potentiator’s involvement becomes both personal and transpersonal. This has the gentle and direct effect of opening the Potentiator to deeper levels of understanding and possibility. As a community of practice we are granted a creative and empowered access to an axiological perspicuity that opens our eyes to existing and/or emergent potentials for addressing the issues at hand.

Interacting

As a Potentiator progresses through the Integral Space they begin discussing and interacting with others within the community of practice in order to reveal the nature of their collective potentials (skills, experiences, talents, aptitudes, perceptions…etc.) concerning existing problems and/or emerging opportunities. Given the valuing component granted them each a sense of axiological perspicuity, the stage is set for creatively engaging these problems and opportunities with another. This interrelational approach is, in effect, an ontological introspection aimed at enriching the container of creative possibilities that is constantly evolving within the Integral Space. As a community of practice we are seeking the goodness of fit of these possible solutions via our collective experiences and knowledge. This serves as a bridging function as the transdisciplinary, transcultural, trans-spiritual, and transpersonal are engaged and incorporated into solving problems and approaching opportunities. Interacting as an element within the dynamic serves an expansive and enriching function.

Transacting

As this integral dynamic flow continues, we begin the process of discussing practical actions or solutions towards addressing the real issues we face; be it problems or opportunities. This neo-pragmatic approach is all about working cooperatively and transactively (the bridging of the objective/subjective dichotomy) towards putting theory into practice and/or informing theory through practice. To remain connected to both substance and essence, as well as creativity and solution, the Potentiator becomes transactive. This allows the Potentiator a way to avoid the epistemological trap of locking on to an idea or to a fixed solution. When we lock on we also have a tendency lock out. As a direct result of locking on to an idea or solution we become defensive in our position. Violence once again emerges as a direct result of this limiting epistemological razor. The creative natures float away being too enigmatic to be held by a guarded position. Transactivity can be seen as a neo-pragmatic method that dissolves the polarity between the subjective and the objective into a more primordial, original situation of understanding, characterized instead by a spaciously creative and practical structure (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2000). Transactivity concerns the revelation of something hidden, some greater whole, rather than the correspondence between subjective thinking and the objective reality. Held within the element of Transacting is the innocent eye of enlightenment and transcendence. This effort embraces transdisciplinarity as well as the transcultural and trans-spiritual experience of the community of practice. The ultimate goal of this aspect of the dynamic is to seek ways in which to put knowledge and/or wisdom to work in the world for the betterment of all. Neo-pragmatism might best be described as an ontological relationship aimed at achieving our mutual and farther reaching purposes.

Transforming

The final element of this integral dynamic— this Integral Space—rests within what might best be called epistemological perspicuity. This construct can be defined as holding knowledge and wisdom as an evolving development and transformational process over a fixed truth. Truth, as an epistemological product, has too often carried with it an arresting effect on creativity and transformation. Given the neo-pragmatic flow of the element of transacting, truth is not seen as an absolute but a moveable and usable construct for understanding the nature of reality. Neo-pragmatism, in terms of actualizing transactivity, holds a blatant disregard for truth as a fixed construct. If a truth or theory is seen as practical the neo-pragmatist is an early adopter, and if not, the same is simply held as unusable in a transactive sense. Thus, the neo-pragmatist is seen as having an ability to place theory into practice and able to contribute to theory through the experience of good practice.

In the end, as was William James’ (1907) complaint, the neo-pragmatist is simply unable to make truth a representation of reality which tends to be the empiricist’s desire. Reality, according to the neo-pragmatist, is to be revealed and experienced. Truths, portable or otherwise, were relative or practical only as long as they provided a tool for that reveal. Truths were easily seen as mutable and relative to an interpretive dialog. This was a great concern to the epistemologist and to the empirical sciences. Neo-pragmatism, when treated as an epistemological construct, fails at every measure because it violates too many empirical conventions. For that reason it is quite easy to attack neo-pragmatism with the deconstructive tools of post-modernism. However, when neo-pragmatism is treated as an ontological construct it is exceptionally informative and nearly impossible to attack using any epistemological/empirical razor. The element of transforming grants us a transformative purpose that is fully informed by our collective knowledge and understanding. Within this vector we are not only transforming our purposes into products aimed at solving existing problems, creating approaches to emerging opportunities, or actualizing our potentials; we are also reconfirming the dynamic flow of the Integral Space by moving again reflexively to continuously value the products of our efforts. As such, the dynamic begins again. This is the Integral Space. This is the integral dynamic (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Integral Space

Experiential Learning

Experiential learning is an active process, one “through which individuals construct knowledge, acquire skills, and enhance values from direct experience” (Association of Experiential Education, 1995). Through self-reflection, critical analysis, and synthesis of carefully chosen experiences, a primary objective of experiential learning is to instill within the individual learner a sense of ownership and responsibility (Luckner & Nadler, 1997, pp. 3-4). Relating experiential learning as an integral construct can be quite informing for the integral leader—for the Potentiator. In examining the full relationship between experiential learning and integral leadership we might find that:

- Experiential learning, by design, seeks to put knowledge and wisdom to work in the world. It bridges theory and practice that aids in transdisciplinary efforts typically found within the Integral Space.

- Experiential learning naturally engages as a transformative, developmental, and innovative process.

- Experiential learning illuminates interrelationships currently at work within the Integral Space.

- Experiential learning as a tool for leaders accentuates their ability to model good practices.

- Experiential learning potentiates interactions and therefore serves and reinforces the bridging actions held by integral leadership.

- Within the Integral Space, experiential learning reveals the deep-seated connections between inspiration, innovation, and implementation.

We can further understand experiential learning as an integral construct by first laying the foundations of a solid andragogical and metagogical awareness.

Accordingly, one of the purposes of this paper is to first deepen our present understanding and awareness of the assumptions of andragogy and metagogy as a set of assumptions by creatively integrating them with principles of experiential learning. This will ultimately illuminate clues for the employment of the experiential learner within this Integral Space and, further, towards integrating these approaches with the nature of integral leadership. This integration activates andragogy and metagogy by way of creating a developmental perspective made possible through experiential learning. This process will in turn make it possible to generate a fresh and overarching connective reality between these approaches to teaching and learning (andragogy and metagogy) with experiential learning, thereby transforming the assumptions of andragogy and metagogy into practical tools for enhancing learning within this Integral Space.

Approaches to Learning

As thoughts, ideas, knowledge, disciplines, cultures, spiritualties and wisdom move into this Integral Space there must be something, some attitude, which is pulling them towards this whole. Socrates stated that “wisdom begins with wonder” and it is likely that that attitude, “wonder”, is at the hub of our Integral Space. The ultimate draw might just be simple curiosity and the innate human drive to be creative. Experiential learning captures that attitude and it is augmented by andragogical (the teaching of adults or adult learning) and metagogical (the teaching to and learning from human potential) approaches to learning.

What if we could improve the quality and focus of the nature of that learning within this Integral Space? What if we discovered a way in which the assumptions held by andragogy as well as the farther reaching aspects of metagogy could be driven with active intent within the community of practice — within the Integral Space? We believe that such a discovery awaits us as these approaches to learning join with other disciplines, cultures, and spiritualties at the integral. It is an orientation that inspires wonder, cultivates creativity, and heightens the ability to generate interactions and interrelations across the span of various disciplines, cultures, and spiritualties. A sense of wonder, encouraged by experiential learning, will build bridges within the Integral Space. Therefore, it would seem critical for learning leaders, for Potentiators, who wish to engage this Integral Space to have at their reach a greater understanding into the nature of teaching and learning.

In a real sense, the process of creating a developmental point of view for andragogy and metagogy, through its active and purposeful integration with principles of experiential learning, can be linked to the emerging dominant teaching perspective in North American adult and higher education: the Developmental Perspective (Pratt and Associates, 2005, p. 45). Of the four additional prominent teaching perspectives including Transmission, Apprenticeship, Nurturing, and Social Reform, it is the Developmental Perspective’s emphasis on cultivating new ways of thinking by accessing the learner’s prior knowledge or experience that aligns itself most closely with the core principles of experiential learning. This can be seen as having a direct influence in understanding the developmental meta-theories surrounding integral leadership. The Developmental Perspective advances the following seven principles (Pratt, 2005, p. 112):

1. Prior knowledge is key to learning.

2. Prior knowledge must be activated.

3. Learners must be actively involved in constructing personal meaning.

4. Making more, and stronger, links [i.e. between theory and practice, the known and the unfamiliar] requires time.

5. Context provides important cues for storing and retrieving information.

6. a. Intrinsic motivation is associated with deep approaches to learning.

b. Extrinsic motivation and anxiety are associated with surface approaches to learning.

7. Teaching should be geared toward making the teacher increasingly unnecessary: the development of learner autonomy as well as the intellect.

These Developmental Perspective principles share much in common with the principles of experiential learning, andragogy and metagogy. If applied correctly, the fundamental principles of the Developmental Perspective will aid Potentiators in “build[ing] bridges between learners’ present way of thinking and more desirable ways of thinking. . .” (Pratt, p. 47), which is likewise a desired outcome of integral leadership. In sum, the Developmental Perspective emphasizes “qualitative change in the learners rather than a quantitative one; learning has to do with knowing differently rather than knowing more” (p. 117).

Intersections of Experiential Learning, Andragogy and Metagogy: Laying the Foundation

An opportunity exists to explore the convergence of experiential learning with andragogy and metagogy in order to enliven each theory’s respective core principles as it relates to integral leadership. This exploration will facilitate the answering of the following questions: How do the principles or values of experiential learning extend current educational perceptions of andragogy and metagogy? How do the assumptions of andragogy and metagogy enlighten current application of experiential learning? More importantly, how does one transform these approaches’ rather abstract assumptions into a real, usable tool to enhance learning within the Integral Space?

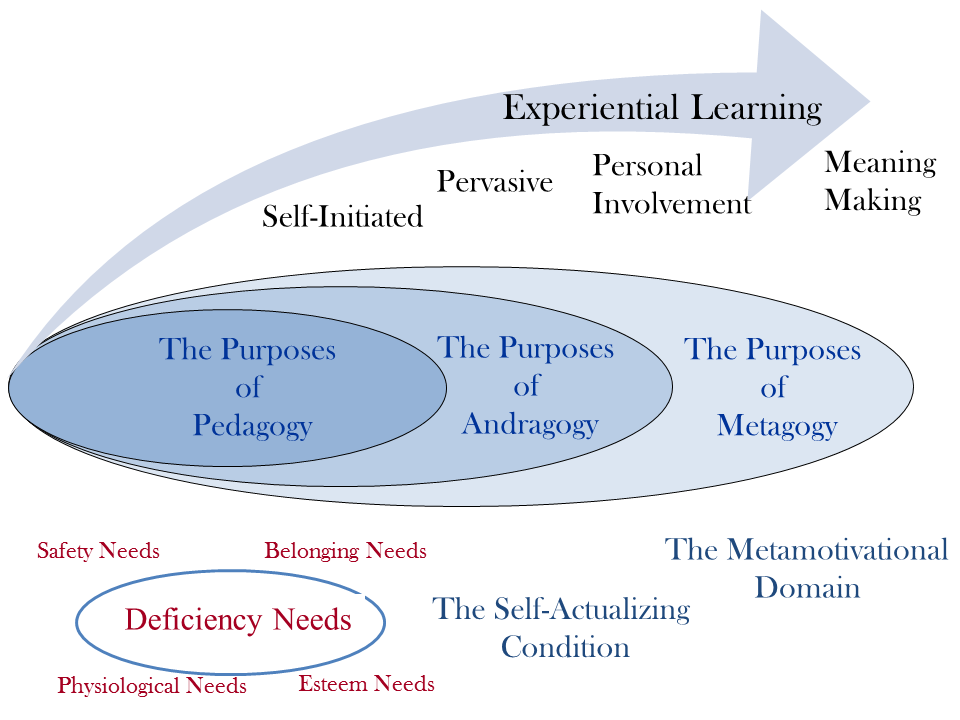

This intersection of experiential learning with andragogical and metagogical approaches to teaching and learning immediately reveals the nature of the self-actualizing condition as an emergent dimension held within this Integral Space that catalyzes this potentiating relationship into a meaningful, one might even say purposeful, bridging action. A deeper examination of this intersection reveals a powerful development mechanism for moving an individual towards the self-actualizing condition and beyond. It is important to note that within this intersection, self-actualization is considered a dynamic developmental process and not a single point on the growth horizon. Thus, we say the individual is in the process of self-actualizing and not self-actualized. Maslow (1971) anchors this concept by reporting that the growth of self-actualizing individuals continues even as they achieve the farther reaches of their metamotivation (Maslow, 1971) and/or as they locate the metamotives to be discovered within the Integral Space.

Individuals having satisfied their deficiency needs (physiological, safety, belonging, and esteem) become increasingly represented by an emergent set of characteristics common to self-actualizing individuals (i.e., acceptance, spontaneity, problem centering, creativity, humor). It is on this slope of self-actualization where the “being values” are discovered and the individual becomes motivated in higher ways to be called metamotivational (Maslow, 1971). Purposeful experiential learning activities that are supported by an andragogical and metagogical framework create a unique outcome supporting both the construction of directly usable knowledge as well as footholds for growth along the self-actualizing continuum towards metamotivation. Examining the intersectional plain, the active intent of experiential learning and the assumptions of andragogy, reveals the growth path held by the self-actualizing condition. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Activating the Growth Path through Experiential Learning

Before proceeding to the convergence of experiential learning with andragogy and metagogy, as well as to enhance our understanding of the central principles associated with each, a brief historical overview of both the genesis of experiential learning, the evolution of andragogy in adult education and the farther reaching aspects of metagogy, is in order. This will be followed by a deeper connection to the potential of this intersection to enhance connectivity within the Integral Space.

Experiential Learning and Andragogy: Establishing Bearings

Significant contributors to the growth and status experiential learning currently enjoys in the field of adult education were, among others, John Dewey, Eduard Lindeman, Carl Rogers, and Malcolm Knowles. Each believed that an individual’s experience was foundational to their learning. More than one hundred years ago as a philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer, Dewey constructed a philosophical framework for experiential learning. In his seminal book, Experience and Education, published in 1938, Dewey discussed at length the role of experience in the learning process:

I assume that amid all uncertainties there is one permanent frame of reference: namely the organic connection between education and personal experience; or…some kind of empirical and experimental philosophy….The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative…. For some experiences are mis-educative…any that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth of further experience…engender[s] callousness…produce[s] lack of sensitivity and of responsiveness…. Everything depends upon the quality of the experience which is had (pp. 25-27).

In part, to more thoroughly assess the “educativeness” of a learner’s experience, Dewey proposed a theory of experience which would first aid educators in understanding the nature of human experience through the interaction of two principles—continuity and interaction. These two principles

are not separate from each other. They intercept and unite. . . . Different situations succeed one another. But because of the principle of continuity something is carried over from the earlier to the later ones. . . . Continuity and interaction in their active union with each other provide the measure of the educative significance and value of an experience (pp. 44-45).

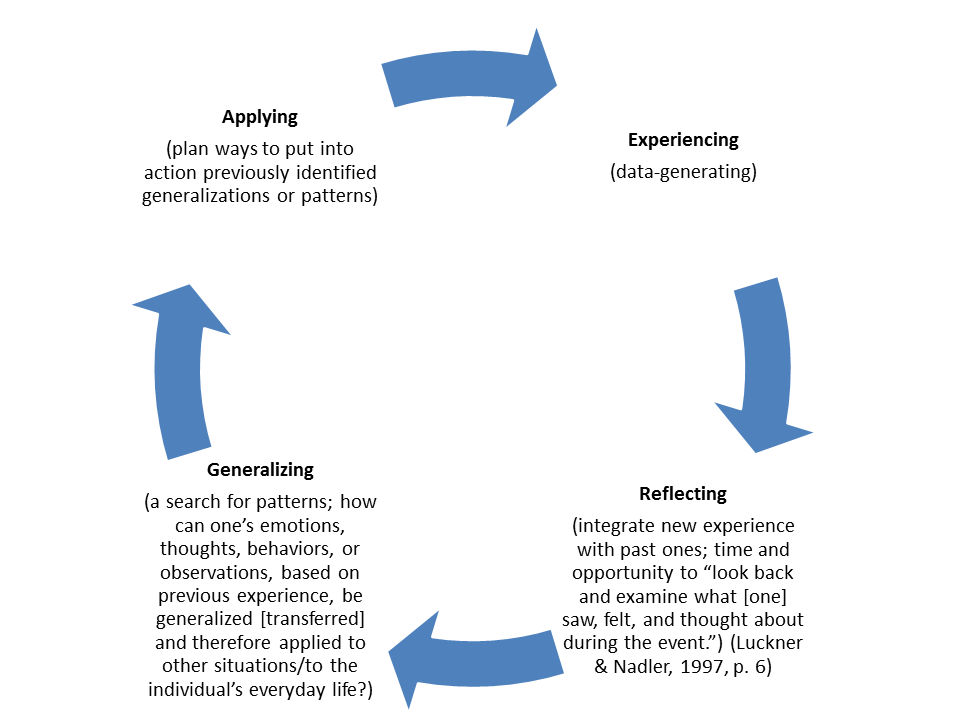

For Dewey, the value of an experience can thereafter be judged by the effect that experience has on a person’s present and future life. Moreover, this theory of experience—of continuity—can be viewed as a precursor to more current experiential learning models or cycles, such as those advanced by Kurt Lewin (1951) and David Kolb (1984); an adaptation of the general 4-stage experiential learning model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. 4-Stage Experiential Learning Model

Dewey, Andragogy, and the 4-Stage Experiential Learning Cycle

At this point, examining the connectedness between Dewey’s experiential learning theory, the experiential learning model/cycle, and the core principles of andragogy provides an example of how andragogy and experiential learning interact. The four stages of the experiential learning cycle/model include: 1) Experiencing: “the structured experience . . . in which individuals participate in a specific activity. This is the data-gathering part of an experience.” (Luckner & Nadler, 1997, p. 5) This stage has clear connections with Dewey’s theory of experience, as both are dependent on the “structured experience.” Likewise, this stage brings to life andragogy “role of the learners’ experience,” the principle that learners’ past experiences can significantly affect or influence their subsequent experiences. This is essentially what Dewey’s theory of continuity and interaction does as well. Thus, both this first experiential learning cycle stage and Dewey’s theory would enhance the practice of andragogy. 2) Reflecting: “experience alone is insufficient to ensure that learning takes place. A need exists to integrate the new experience with past experiences through the process of reflection” (Kolb (1984) as cited in Luckner & Nadler, p. 6).This stage particularly harmonizes with Dewey’s principle of interaction, as well as with the “experience” assumption of andragogy. The reflecting stage further emphasizes the need for the learners to have the time and opportunity, as individuals or in a group process, “to look back and examine what they saw, felt, and thought about during the event” (Luckner & Nadler, p. 6). This stage would also activate the “learners’ self-concept, challenging learners to be more self-directed in their learning. This critical reflection element might also activate the learners’ “motivation,” or internal drive for learning. Moreover, Dewey’s theory of continuity also calls for periods of active reflection, for the “continuity and interaction in their active union with each other provide the measure of the educative significance and value of an experience” (pp. 44-45). 3) Generalizing: this stage calls for individuals to search for patterns based on the specific experience “to explore whether emotions, thoughts, behaviors or observations occur with some regularity. [When such] are understood in one situation, this understanding can be generalized [or transferred in qualitative research] and applied to other situations” (p. 6). Similar to andragogy’s assumptions of “readiness to learn” and “orientation to learning,” the generalizing stage underscores the importance of making inferences from specific experiences and events and applying such to the individual’s everyday life. 4) Applying: In this stage, “individuals are encouraged to plan ways to put into action the generalizations [patterns] that they identified in the previous stage . . . Consequently, the key question of this stage is ‘Now What?’” (p. 6). This application stage would directly activate the “learners’ self-concept,” again calling upon the learner to become more self-directed in the learning process. As a whole, the four stages prepare an individual through their application of learning for the next structured experience. Each of the four stages has distinctive connections with the assumptions of andragogy and with Dewey’s theory of continuity.

Regarding the role that experience plays in education within modern adult learning theory, particularly andragogy, both Eduard Lindeman and Malcolm Knowles were significantly influenced by Dewey’s pioneering work in experiential learning. Known for his revolutionary contributions in adult education, Lindeman, like Dewey, firmly believed that significant experience was paramount in adult learning. From Lindeman’s 1926 publication, Adult Learning, the following excerpts illustrate this point:

. . . the resource of highest value in adult education is the learner’s experience. If education is life, then life is also education. Too much of learning consists of vicarious substitution of someone else’s experience and knowledge…. Experience is the adult learner’s living textbook (pp. 9-10).

Adult education is a process through which learners become aware of significant experiences. Recognition of significance leads to evaluation. Meanings accompany experience when we know what is happening and what importance the event includes for our personalities (p. 169).

In his call for significant experience, Lindeman foreshadowed the use of some instrument to validate one’s experience, such as the widely-used 4-stage learning model or cycle (see Figure 2), when he stated that “experience is, first of all, doing something; second, doing something that makes a difference; third, knowing what difference it makes” (1926, p. 138). In this context, and in relation to experiential learning, learning may be described as a “process of making sense of life’s experiences and giving meaning to whatever ‘sense’ is made,” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 7) or as “the process whereby knowledge is created through transformation of experience” (Kolb, 1984, p. 38).

For Dewey, Lindeman, and humanist Carl Rogers, it is not enough to simply have the experience. Rogers, in fact, equated significant learning with experiential learning, or learning that leads to personal growth and development. Experiential, as opposed to cognitive, learning also makes the learners’ needs and wants a priority. Thus Rogers (1983) proposed that experiential learning consists of the following principles or characteristics (as cited in Merriam & Caffarella, 1999, p. 258):

1. Personal involvement: the affective and cognitive aspects of a person should be involved in the learning event.

2. Self-initiated: a sense of discovery must come from within.

3. Pervasive: the learning “makes a difference in the behavior, the attitudes, perhaps even the personality of the learner.”

4. Evaluated by the learner: the learner can best determine whether the experience is meeting a need.

5. Essence in meaning: when experiential learning takes place, its meaning to the learner becomes incorporated into the total experience.

Rogers’ keys to significant or experiential learning not only contributed to adult learning theory, but they clearly influenced Knowles’ theory of andragogy.

Malcolm Knowles was decidedly influenced by Eduard Lindeman’s educational philosophy for adults. In Knowles’(1984) opinion, Lindeman had “laid the foundation for a systemic theory about adult learning” (p. 28). As a noted contributor to the field of adult education and primary proponent of andragogical learning in the United States, Knowles, in his landmark book, The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy (1980), expressed the following regarding experiential learning:

The central dynamic of the learning process is thus perceived to be the experience of the learners; experience being defined as the interaction between individuals and their environment. The quality and amount of learning is therefore clearly influenced by the quality and amount of interaction between the learners and their environment and by the educative potency of the environment…environment and interaction—which together define the substance of the basic unit of learning, a “learning experience” (p. 56).

Knowles’ above-expressed vision of the learners’ experience was likely influenced by Dewey’s theory of continuity discussed previously. In a sense, Knowles’ principles of “environment and interaction,” and Dewey’s “continuity and interaction” are respectively compatible, each a prerequisite to forming a person’s “learning” (Knowles) or “present” (Dewey) experience. Having established a historical perspective of the role experience plays in the adult learning process as seen through the eyes of Dewey, Lindeman, Rogers and Knowles, we now turn to a historical look at andragogy’s evolution over the years, including its potential connections with experiential learning.

Origins of Andragogy

Its roots previously established in early twentieth-century European adult education (Fidishun, 2000; M. Knowles, 1984; Merriam & Caffarella, 1999; Zmeyov, 1998), andragogy continues to be a buzzword in the realm of education, particularly within institutions of higher education. One may trace the term andragogik back to German grammar teacher, Alexander Kapp, who is thought to have first coined the word in 1833 (M. Knowles, 1984; M. Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2005), and to fellow German Social Scientist, Eugen Rosenstock (Fidishun, 2000; M. Knowles, 1984). The latter claimed in 1921 that “adult education required special teachers, special methods, and a special philosophy” (as cited in Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 1998, p. 59).

The concept of a unified theory of adult learning, as opposed to the theory of youth learning, with its corresponding label pedagogy, was first introduced to Malcolm Knowles in 1967 by the Yugoslavian adult educator, Dusan Savicevic (Knowles, 1984). Shortly thereafter, in April 1968, Knowles introduced Savicevic’s ideas to America in his Adult Leadership article, “Androgogy, Not Pedagogy,” wherein he proposed using the word andragogy to characterize the education of adults. Other renown educators and thinkers, including Brookfield (1968), Mezirow (1991), Lawler (1991) and Merriam (1999) continue to discuss andragogy’s fundamental assumptions and how they may be utilized to encourage and facilitate the adult learning process.

Knowles (1980) originally defined andragogy as the “art and science of helping adults learn” (p. 43). This is not to imply, however, that the underlying educational assumptions of andragogy may not be applied to the pedagogical model of teaching children. As Knowles further clarified, “whenever a pedagogical assumption is the realistic one, then pedagogical strategies are appropriate, regardless of the age of the learner—and vice versa” (p. 43). This being said, “andragogy is basically a humanistic theoretical framework applied primarily to adult education”(Elias & Merriam, 1995, p. 131). Elias and Merriam further note that Knowles is

indeed a humanistic adult educator. For him, the learning process involves the whole person, emotional, psychological, and intellectual. It is the mission of adult educators to assist adults in developing their full potential in becoming self-actualized and mature adults. Andragogy is a methodology for bringing about these humanistic ideals. (p. 133)

What precisely, then, are Knowles’ unique beliefs underscoring the adult educational theory known as andragogy? Outlined below, andragogy is based on six assumptions about the adult learner, in that as a person matures into adulthood:

1. [The need to know] they need to know why they need to learn something before undertaking to learn it (M. Knowles, 1984, p. 55).

2. [The learners’ self-concept] their self-concept moves from one of being a dependent personality toward being a self-directed human being;

3. [The role of the learners’ experiences] they accumulate a growing reservoir of experience that becomes an increasingly rich resource for learning;

4. [Readiness to learn] their readiness to learn becomes oriented increasingly to the developmental tasks of their social roles; and

5. [Orientation to learning] their time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application, and accordingly, their orientation toward learning shifts from one of subject-centeredness to one of performance-centeredness (M. Knowles, 1980, pp. 44-45).

6. [Motivation] they are motivated to learn by internal factors rather than external ones (Knowles and Associates as cited in Merriam & Caffarella, 1999, p. 272).

To Knowles’ original set of four adult learner assumptions, assumption number 6, motivation to learn, and assumption number 1, the need to know, were added and subsequently published as early as 1984. Thereafter, Knowles’ “model of assumptions” (1980, p. 43) has served as the distinguishing foundation of andragogy, which “became a rallying point for those trying to define the field of adult education as separate from other areas of education” (Merriam & Caffarella, 1999, p. 273).

Experiential Learning and Metagogy: Beyond Teaching

McCaslin and Scott (2012) coined the word Metagogy (the teaching to and learning from potential) as way of understanding their observations stemming from the construction of a learning community. This particular community of practice, in retrospect, might well have been seen as integral education in action. The demonstrated integral leadership attributes discovered through the exploration of metagogy effectively extended and enhanced the ability of Potentiators to engage within the Integral Space. In pedagogy and in andragogy the objectives are predetermined, whether teacher-directed or teacher-guided and learner-self-directed. The goal of each educational model is to deductively determine learning objectives and to structure curriculum toward their achievement. McCaslin and Scott (2012) assert that metagogy begins with the following assumptions:

- The usual state of teaching, therefore learning, is suboptimal (less than interdependent). In reality it may be described as clouded, distorted, lacking purpose, and largely unconnected to the typical learner. Where the focus is currently on the content (i.e., teaching to an objective), it should rightly be on the learner (i.e., teaching to a person with his or her own objectives). The optimal state occurs naturally at the intersection of potentials – those of the learner and those of the teacher (the Potentiator).

- While teaching and therefore learning may be suboptimal, this state can be resolved by methods that catalyze personal potentials for both teaching and learning.

- Awareness and reflection lead to sensitivity for the human potentials before us leading towards, perhaps, the greatest skill required by the Potentiator– the ability to learn from, and about, the very ecologies of the learner. In truth, education does not rest beyond that point, but within it.

- Intentions move away from objective-orientation and toward potentiated growth of the student.

Metagogy seeks to inductively catalyze open-ended inquiry in a community of learners in such a way that the synergistic flow of learning inductively discovers the questions appropriate to reach correspondingly appropriate truths for each community member and thereby, for the community as a whole. Catalytic teaching (metagogical inquiry) potentiates “ah-ha!” understandings, stimulating the learner to make a quantum leap (borrowing a term from physics), a stepping straight up in moving to a higher understanding of a new concept. Once that new understanding is attained, the learners’ perspectives are broadened, clarified, fitting more of the puzzle pieces together. At the same time they become metamotivated to intrinsically reflect on their learnings to more fully understand their own potential and to extrinsically share their transformations with others to expand the potential of the collective. This is neither a push nor pull; a lift nor carry, but an essential relationship of metagogical teaching and learning (McCaslin and Scott, 2012).

Psychologists tend to agree that, relative to a needs hierarchy, people satisfy survival needs and belonging or community needs before reaching toward what Maslow refers to as growth needs. As people mature, they seek and reach autonomy on several levels, the highest of which include Maslow’s self-actualization and transcendence (Maslow, 1971), Loevenger’s interdependent and integrated appreciation for other’s needs and views (Carver & Scheier, 1996); Kolberg’s universal ethical principle orientation (Kolberg, 1963), Roger’s fully-functioning person (Rogers, 1961), Csikszentmihalyi’s flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1988). These high functioning states allow for developing one’s potential and having great appreciation for multiple views within a community, while maintaining one’s own view free of any defensive posture.

Buscalia (1978) suggests that realizing maturational potentials are entirely within the individual. Metagogy recognizes this and seeks not to “push,” “pull,” or “lift” the individual, but rather to potentiate him or her to find the personal inspiration within to reach higher toward his or her own goals for uniquely personal reasons (McCaslin and Scott, 2012).

According to McCaslin and Scott (2012) the elements of metagogy are as follows:

- Pure pleasure of learning for its own sake

- “Pull” of commitment to learning through personal inspiration and intrinsic passion

- Betterment of community not a goal, but a natural by-product of seeking highest potentials in an interconnected manner

- Developing one’s potential, interdependently catalyzing and catalyzed by the learning community, thereby contributing to developing community potential

- A requisite towards ethical teaching (view ethics not in terms of conventional morality but rather as an essential principle for teaching and learning)

- Embraces Maslow’s (1971) metamotivational values

- Acknowledges learning as a dynamic and synergistic relationship contributing to the creation of opportunities used to address personal destinies within community

- Inspires the cultivation of wisdom “whereas knowledge is something we have, wisdom is something we become. Developing it requires self-transformation” (Walsh and Vaughn, p. 51, 1993).

The practice of metagogy presents an opportunity to evolve a new approach to teaching and learning that engages and potentiates the farther reaches of a community of learning (McCaslin, 2013). In observing the qualities of Potentiators that can be seen and felt, it became clear to that these Potentiators are able to hold space for Acts of Potentiation for themselves and others (McCaslin 2013). These Acts of Potentiation inform the Integral Space.

Acts of Potentiation

The Acts of Potentiation include seven integrated practices and form the foundation of the Potentiating Arts™ (McCaslin, 2013). Beginning with Deep Understanding, the Potentiator seeks to develop empathetic considerations. Critical Reflection encourages inspired learning. Practicing Maturity, through awareness, insight, and discernment illuminates a landscape full of possibilities. The practice of Empowerment and Authenticity work in tandem to seek the cultivation of mutuality and interdependence as well a way to fully embody our original greatness. Cultivating Synergy in another set of practices developed in tandem. The notion of Cultivation invites the Potentiator to become a community builder. Finally, the practice of Synergy invites all to that place towards becoming a well-being. McCaslin (2013) explains the integral dimensions of these integrated practices as follows:

- Deep Understanding. The practice of Deep Understanding begins with one simple question: Are you ready to learn? It embraces a conscious movement away from prejudgment towards a more true understanding of the gifts of potential held by another and self. It is deeply rooted in empathy. It is not a directive or controlling stance but a purposeful probe into the meaning of the experience shared with another. It supports of the full actualization of human potential without a need for defining or confining—without the need for violence. It is foundational for empowering creativity, curiosity, and wonder.

- Critical Reflection. Practicing Critical Reflection is the purposeful act we take to deeply connect with where we are as a learner within any human ecology. To put it simply, through critical reflection we become more deeply aware of our purpose, place, and of the impact our interactions are having on other people and our environment. What separates critical reflection from other types of learning or reflection is held within its intention to pry deeply into our individually held assumptions concerning how we interact with others. Critical reflection is a very personal practice aimed at revealing a deeper self-awareness. Are you ready to become creatively self-aware?

- Maturity. Practicing Maturity can be seen as the ability to recognize, and then come to an insightful and authentic appreciation for, the creative efforts of another. Through practicing maturity, we come to recognize the good person in another even when they are shrouded in the fog of self-doubt, self-deception, self-destruction and self-reproach; to hold the wisdom to know that beneath these exteriors that there is always a better explanation and deeper meaning for a person’s poor and/or unhealthy behavior than what is readily apparent on the surface. To reach through the mire into the very heart and soul of another and to lift from it the possible person – this is what it means to potentiate, this is true courage—this is maturity.

- Empowering Authenticity. Practicing Empowering Authenticity is essentially a way towards cultivating and sustaining the authentic self. The practice of Empowering Authenticity concerns itself with integrating our inward and outward selves. Through this practice our thoughts, words, and deeds come into alignment. The harvest waiting those practicing Empowering Authenticity is a greater reach into the gifts of potential within our own being as well as others. It is essentially a way towards our highest self that is presented by a willingness to explore our own being, inwardly and outwardly, as it relates to the human ecology. Empowering Authenticity is fundamentally a skill centered upon self-exploration and emotional intelligence. Empowering Authenticity requires a setting of intentions. It asks: Are you ready to become in reality what you appear to be?

- Cultivating Synergy. Cultivating Synergy is represented by the landscape of relationships and our interaction with the everyday aspects of living; to position the individual and community for an everyday transcendence. From deep ecology; Cultivating Synergy represents a fusion of individually held potentials with the environment in which it actualizes (a sacred habitat); the celebration of the rich diversity of human potentials while at the same time establishing a sense of conservation and respect for the community, society, and the world. This is the path toward a synergistic society. Am I ready to participate fully within this community of potential? Am I prepared, within and without, to become a well-being?

The Acts of Potentiation harmonize quite easily with experiential learning and further still as an essential construct at work within the Integral Space.

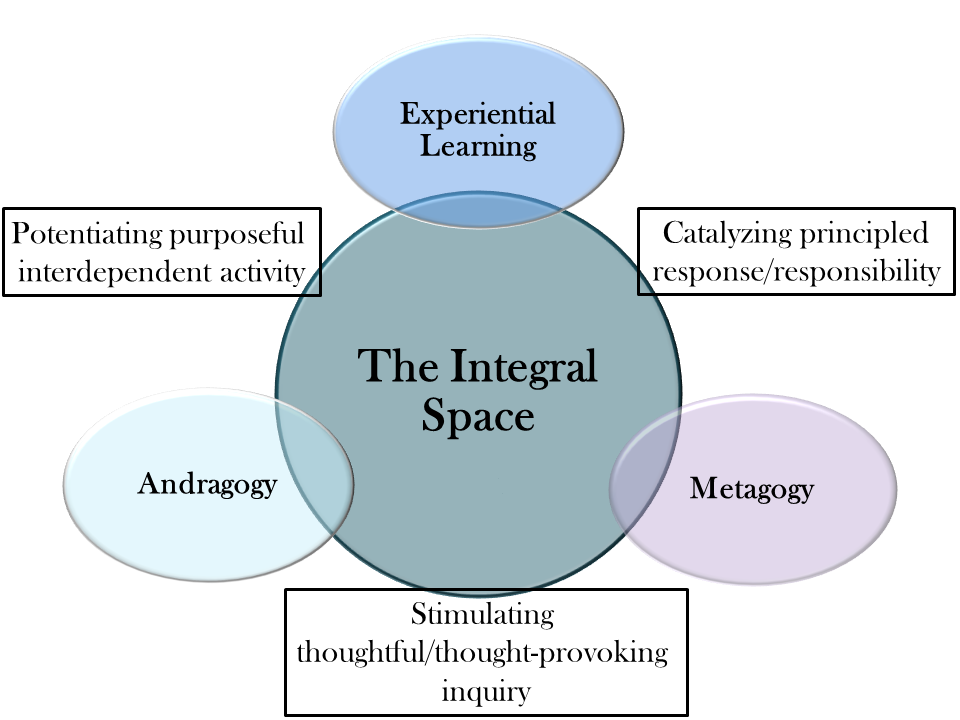

Living, Learning and Leading within the Integral Space

Experiential learning, coupled now with a greater understanding of andragogy and metagogy as approaches to teaching, learning and potentiating, provides a creative and engaging way to live, learn, and lead within the Integral Space. Metagogy catalyzes and actualizes the human potential within the Integral Space via acts of potentiation. It is the teaching to and learning from potential. “Stimulating learning through thoughtful/thought-provoking inquiry, potentiating contributions as well as participation—an intervention of the highest sort—a purposeful interdependent activity serving to catalyze principled response and responsibility is what we call catalytic teaching; it is the enlivening force of metagogy” (McCaslin and Scott, p. 1, 2012). The building blocks for constructing an integral approach to living, learning and leading within the Integral Space can be constructed from these philosophical attitudes: 1) Stimulating learning through thoughtful/thought-provoking inquiry ; 2) Purposeful interdependent activity; and, 3) Catalyzing principled response and responsibility.

These building blocks will then be further strengthened by the basic principles underlying experiential learning in general. Adapted from the Association of Experiential Education, 1995; Kraft & Sakofs, 1985; and Weil & McGill, 1989, Luckner and Nadler (1997, p. 4) have created the following compilation of the principles of experiential learning:

- The learner is a participant rather than a spectator in learning.

- Experiential learning occurs when carefully chosen experiences are supported by reflection, critical analysis, and synthesis.

- Learning must have present as well as future relevance for learners and the society in which they will participate.

- Throughout the experiential learning process, learners are actively engaged in posing questions, investigating, experimenting, being curious, solving problems, assuming responsibility, being creative and constructing meaning.

- Learners are engaged intellectually, emotionally, socially, and/or physically. This involvement helps produce a perception that the learning task is authentic.

- Individuals may experience success, failure, adventure, risk-taking, and uncertainty, since the outcomes of experience cannot be totally predictable.

- Educator’s primary roles include: structuring appropriate experiences, posing problems, setting boundaries, supporting learners, insuring physical and emotional safety, and facilitating the learning process.

- Educators must recognize and encourage spontaneous opportunities for learning.

- The design of the learning experience includes the possibility to learn from natural consequences, mistakes, and/or successes.

- Learners develop an in-depth understanding of what theory from reading or lectures might mean in actual practice.

- The results of learning are personal and form the basis for future experiences and learning.

- Relationships are developed and nurtured; learner to self, learner to others, and learner to the world at large.

- Educators strive to be aware of their biases, judgments, and pre-conceptions and how they influence the learner.

- Individuals increase their awareness of how personal values and meanings influence their perceptions and choices of action.

- Educators use a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of real-life problems.

The opportunity now exists to clearly identify the importance of weaving these experiential learning elements as they harmonize with andragogy and metagogy within the Integral Space.

Potentiating Purposeful Interdependent Activity

The learner is a participant rather than a spectator in learning. The “learners’ self-concept,” a primary assumption of andragogy, is clearly activated by this experiential learning (hereafter referred to as EL) principle as the adult learner becomes increasingly self-directed through active participation. This EL principle, likewise, emphasizes the essential participatory nature of the remaining assumptions. Participatory learning over passive engagement is also at the heart of andragogy’s “need to know,” wherein learners are engaged as collaborative partners in their learning. The learner must clearly be participatory, not passive, if they are to activate andragogy’s “role of the learners’ experience.”

Convergently, it is perhaps the andragogical assumption of the learner’s “readiness to learn,” which in part calls on facilitators to prepare learning experiences appropriate to learners’ developmental stages that would activate this core EL principle of participation. Similarly, activating andragogy’s “orientation to learning,” which emphasizes life-and-task-centered learning within the context of one’s work, family, and community, would likely spur the learner towards active involvement over passivity. Finally, if one is internally motivated, learners are apt to be participants, and not spectators, in their learning.

Individuals increase their awareness of how personal values and meanings influence their perceptions and choices of action. This EL principle connects most strongly with the learners’ “self-concept” and “role of their experiences.” Likewise, these specific andragogical assumptions could mutually influence this EL principle.

The results of learning are personal and form the basis for future experiences and learning. The engagement of adults as collaborative partners (“need to know”), learners taking charge of their own learning via increased personal self-directedness (“self-concept”), learners using past experience to enhance future ones (“role of the learners’ experience”), timing learning experiences to coincide with learners’ personal developmental stages (“readiness to learn”), providing learning experiences that are life and task-centered and personally connected to the learners’ work, family, and community (“orientation to learning”), and the learner’s inner drive through their increased desire for self-esteem, quality of life (“motivation”) — each an andragogical assumption — are personally connected, in varying degrees, to the learner on an individual basis.

Relationships are developed and nurtured; learner to self, learner to others, and learner to the world at large. To varying degrees, each of andragogy’s assumptions share connections with this EL principle and could enhance its emphasis on development and nurturing. Consider, for example, the “learners’ self-concept:” as the learner becomes more self-directed in their learning, they likewise learn more about themselves, which in turn would optimally influence their capacity for future self-directed learning. In addition, the relationships of learner to others and learner to the world at large would be developed/nurtured more specifically by the learners’ “need to know” (collaborative partners in learning), and “orientation to learning” (emphasizing life-centered and task-centered learning experiences that are relevant to the learners’ “others:” work, family, and community).

Educators strive to be aware of their biases, judgments, and pre-conceptions and how they influence the learner. From the educator/facilitators’ point of view, this EL principle must become a reality in authentic applications of andragogy. Each of andragogy’s assumptions could be more successfully realized through honest application of this principle. Such awareness has the potential to create, in Dewey’s terms, either educative or mis-educative learning experiences.

Stimulating Thoughtful/Thought-Provoking Inquiry

Experiential learning occurs when carefully chosen experiences are supported by reflection, critical analysis, and synthesis. This EL principle activates the andragogical assumption “role of the learners’ experience.” Through the experiential learning process partially embodied in reflection, critical analysis, and synthesis, the adult learner’s prior experiences come to bear on his/her future experiences.

Throughout the experiential learning process, learners are actively engaged in posing questions, investigating, experimenting, being curious, solving problems, assuming responsibility, being creative and constructing meaning. The active engagement required in this EL principle would activate the andragogical learners’ “self-concept,” as well as the “role of the learners’ experience” in that it would encourage greater self-directedness, while causing the adult learner to draw from his/her reservoir of past experiences in the process of being actively engaged in specific activities such as those noted above.

Andragogy, in a fashion similar to the experiential learning principle first discussed above, could likewise enhance the experiential learning process. The “need to know” assumption, wherein learners are engaged as collaborative partners in their learning, could very well drive the experiential learning process described in this principle. The “role of the learners’ experience” could very well come into play here, for learners’ previous experiences—both positive and negative—will likely influence the degree to which the learner becomes actively involved in posing questions, solving problems, and so forth. The learner’s “readiness to learn,” which in part calls on facilitators to prepare learning experiences appropriate to learners’ developmental stages, would also tend to activate this EL principle’s “active engagement” emphasis. Similarly, andragogy’s “orientation to learning,” emphasizing life-and-task-centered learning within the context of one’s work, family, and community, could possibly spur the learner towards greater active engagement. Finally, if one is internally motivated, learners are apt to be more actively engaged in their learning.

The design of the learning experience includes the possibility to learn from natural consequences, mistakes, and/or successes. This EL principle activates the “role of the learners’ experience,” as learners’ previous “mistakes” and “successes” will optimally influence future experiences within the experiential learning cycle. The “learners’ self-concept” assumption could likewise become more active as the individual, learning from these past “mistakes” and “successes,” takes greater responsibility for their future learning.

Learners develop an in-depth understanding of what theory from reading or lectures might mean in actual practice. This specific EL principle encompasses the essence of experiential learning—learning through doing. Sakofs’s research finds that experiential learning “values and encourages linkages between concrete, educational activities [the actual practice] and abstract lessons [the theory] to maximize learning” (as cited in Luckner & Nadler, 1997, p. 3). Experiential learning, therefore, helps move the theoretical to the actual, the practical. The principles of experiential learning in general would enhance andragogy’s application. Or, perhaps from another viewpoint, could not the overarching principles associated with experiential learning be viewed as “actualizers,” helping to move andragogy from an educational theory to a more active, usable tool in adult education?

Catalyzing Principled Response/Responsibility

Learning must have present as well as future relevance for learners and the society in which they will participate. This principle has multiple connections to andragogy. It activates the learner’s “need to know” in that it involves learning that makes a personal impact in the learner’s lives. It likewise activates the “role of the learners’ experience.” This principle makes active the learners’ “readiness to learn,” timing learning experiences to coincide with an individual’s developmental stages, along with the learners’ “orientation to learning,” which calls for life and task-centered experiences, allowing adults to learn within the contexts of work, family, and community. Finally, this principle of EL could potentially activate the adult learner’s inner “motivation to learn,” for “the learning that adults value the most will be that which has personal value to them” (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2005, p. 200).

Learners are engaged intellectually, emotionally, socially, and/or physically. This involvement helps produce a perception that the learning task is authentic. “Authentic” experiential learning tasks activate the learners’ “need to know” through activities that will make a personal impact in the individuals’ lives. Authenticity would likewise contribute to the problem-centered, contextual nature of the andragogical learners’ “orientation to learning.” Finally, authentic learning tasks may increase learners’ “motivation to learn” to the degree that the task’s intrinsic value and personal payoff are perceived by the learner.

Individuals may experience success, failure, adventure, risk-taking, and uncertainty, since the outcomes of experience cannot be totally predictable. Failure is impossible! What we are really talking about here is the potentiating nature of freedom. Potentiators, understanding the pathway to the full actualization of potential, seek opportunities to move their children, students, or associates toward a healthy independence. In this way freedom becomes perceived as an end value and as a rather useful stepping stone towards our greatest potential. Freedom is a necessary step in the development of our full potential. But it doesn’t have to be a destructive step. As Potentiators we must become comfortable in loosening the reins and in trusting to the instruction we have given our children, students, and associates that has prepared them to accept and demonstrate their capabilities. Will they fail? Of course they will, but there is a value in failing. What we are instilling in them is the value of learning – are they ready to learn? The enduring goodness embodied by “failure is impossible” rightly sets the direction of all acts of potentiation by establishing a prevailing reality that encourages the real growth of potential by way of creativity, imagination, curiosity and play.

Educators must recognize and encourage spontaneous opportunities for learning. This principle surely activates the learner’s “readiness to learn” concept, and calls for adult learning facilitators to be aware of their learners’ developmental stages. If effectively managed, this principle would likewise continue to encourage the self-directed nature of adult learning.

Educators’ primary roles include: structuring appropriate experiences, posing problems, setting boundaries, supporting learners, insuring physical and emotional safety, and facilitating the learning process. This EL principle, as a whole, could make it possible for the adult learner to become more self-directed, helping the “learners’ self-concept” to come alive. This principle would also draw on learners’ past experiences to enhance the learning process. With its emphasis on structuring, the EL principle makes real the learners’ “readiness to learn,” as timing learning experiences to coincide with learners’ developmental stages becomes an increasingly important learning element. Finally, the “structuring” would also help drive home andragogy’s “orientation to learning,” which calls for life-and-task-centered learning within the context of the learners’ work, family, and community.

Empowering the Potentiator

The opportunities to employ these approaches to teaching and learning within the Integral Space seem infinity varied. The three philosophical attitudes of metagogy, the six guiding assumptions of andragogy, and the 15 experiential learning principles can be engaged in myriad ways to support acts of potentiation within the Integral Space. The dynamic is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Teaching and Learning Dynamic within the Integral Space.

Experiential learning aids in revealing our assumptions about the world. Assumptions can make for great signposts as they can assist us in gaining a direction in our search for human potential—a critical part of integral leadership. The Potentiator employs a critical reflective lens in order to prevent their assumptions from becoming limiting or allowing them to ossify whereby they can become growth limiting burdens. The Potentiator recognizes that the assumptions we hold concerning how the world works should be looked at as a set of clues that would guide us forward. If assumptions are allowed to ossify then the Potentiator becomes both hard and brittle and the learner can be left under-potentiated. When we lock on to one single reality or possibility we lock out all others. Experiential learning helps keep the Potentiators assumptions soft, supple, flexible and responsive by way of gaining a sense of a creative self-awareness. Experiential learning holds the ability to heighten the sense of democracy within the Integral Space by welcoming participation as a construct for evoking the reality of a community of practice.

References

Alvesson, M. & Sköldberg, K. (2000). Reflexive methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Brookfield, S. D. (1968). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Buscaglia, L. (1978). Personhood: The Art of Being Fully Human. Thorofare, NJ: CB Slack.

Carlson, N. (2003). Communities of Practice: An Application in Adult Education. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Idaho. Moscow, Idaho.

Carver, C. & Scheier, M. (1996). Perspectives on Personality (3rd Edition). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Coates, D. (1995). The process of learning in dementia-carer support programmes: some preliminary observations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21, 41-46.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Dixon, N.M. (2000). Common Knowledge: How Companies Thrive by Sharing What They Know. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Donald N. Roberson, J. (2002). School of Travel: An exploration of the convergence of andragogy and travel.

Elias, J. L., & Merriam, S. B. (1995). Philosophical foundations of adult education (2nd ed.). Malabar: FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Fidishun, D. (2000). Andragogy and technology: Integrating adult learning threory as we teach with technology. Paper presented at the Mid-South Instructional Technology Conference, Murfreesburo, Tennessee. Retrieved October 22, 2005 from http://www.mtsu.edu/~itconf/proceed00/fidishun.htm

James, W. (1907/1979). Pragmatism. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press.

Knowles, Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. (1998). The adult learner. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education.

Knowles, M. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Chicago, IL: Follett Publishing Company.

Knowles, M. (1984). The adult learner: A neglected species (Third ed.). Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company.

Knowles, M., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. (2005). The adult learner. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kolberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive developmental approach to socialization, in Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research, D. A. Goslin, Ed., Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 347-480.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning-Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lawler, P. (1991). The keys to adult learning: Theory and practical strategies. Philadelphia, PA: Research for Better Schools.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social sciences. New York: Harper & Row.

Lindeman, E. C. (1926). The meaning of adult education. New York: New Republic.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego Development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Love, T. (2001). Fundamental concepts of an experiential andragogical approach to non-traditional experiential learning programs. Volume (Number), PagesA.

Luckner, J. L., & Nadler, R. S. (1997). Processing the experience: Strategies to enhance and generalize learning. Dubuque: Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

MacKeracher, D. (2004). Making sense of adult learning (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking Press.

McCaslin, M.L. (2013). The Alchemy of Potential. Manuscript in preparation.

McCaslin, M.L. & Scott, K.W. (August 2012).Metagogy: Teaching, Learning and Leading for the Second Tier. Integral Leadership Review.

Merriam, S. B., & Caffarella, R. S. (1999). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Pratt, D. (2005). Five perspectives on teaching in adult & higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1983). Freedom to learn for the 80’s. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Walsh, R., & Vaughn, F. (1993). The Art of Transcendence: An Introduction to the Common Elements of Transpersonal Practices. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 25, 1-10.

Weinstein, M. B. (2002). Adult learning principles and concepts in the workplace: Implications for training in HRD. Paper presented at the Adult Learning and HRD Conference, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of Practice: Stewarding knowledge. In C. Despres (ed.) Knowledge Horizons: The Present and the Promise of Knowledge. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.

Zmeyov, S. I. (1998). Andragogy: Origins, Developments and Trends. International Review of Education, 44(1), 103-108.

About the Authors

Dr. Mark McCaslin is a career educator with a rich history of teaching, educational programming, and administration. His personal and professional interests, which have influenced his research, flow around the development of philosophies, principles, and practices dedicated to the full actualization of human potential, with particular focus centering upon organizational leadership and educational approaches. At the apex of his current teaching, writing, and research is the emergence of potentiating leadership and the Potentiating Arts™.

Dr. Jason Flora is a faculty member in the Department of Humanities & Philosophy at Brigham Young University-Idaho where he teaches introductory and upper-division courses in Humanities and the History of Art. His doctoral research uncovered fresh intersections between experiential learning theory and andragogy within the dynamic backdrop of short-term study abroad programs.