Edward J. Kelly

Edward J. Kelly

Abstract

The following is a summary of my developmental research on Warren Buffett. The study concludes that Warren Buffett has gone through seven transformations in leadership and that his character development is largely responsible for his success as a leader.

Introduction

I first became actively interested in Warren Buffett in 1995 having read Roger Lowenstein’s The Making of an American Capitalist. Sometime later I started trying to invest like Buffett and shortly after that, and having experienced how difficult it was, I bought my first share in Berkshire (Buffett’s company) which I still have to-day. Then in 2003, I left the mobile phone distribution company I had set up in 1995 and embarked on a formal study of Buffett for a Ph.D.

My interest in Buffett by this time had turned mostly to understanding his wisdom. Buffett seemed to have a kind of direct knowing of things. He could see into the reality of what was going on and come out with a result that others could only see in hindsight. What was going on with that, I wondered? Later again, my focus shifted to the wisdom of his leadership and that is where my research ended up. As I summarise below, I then wrote a detailed dissertation on development with the forgettable title of, Transformation in Meaning-Making; Selected Examples from Warren Buffett’s Life: A Mixed Methods Study. This study concluded that Warren Buffett had gone through seven transformations of leadership over his long business career and that the development in his character had directly influenced his success as an investor and leader. What began to emerge, however, was that while Buffett may have been hard-wired for success as an investor, he was not hard-wired for success as a leader. His natural logical/mathematical intelligence and rational temperament (his predispositions) adapted him well for the kind of investment environment in which he found himself. But he became a successful leader through his own intentional acts of learning and development. This is the story less told about Buffett: how the development in his character influenced his success as a leader.

Over at least three articles I hope to provide you with a readable summary of my dissertation. This is to distinguish it from the dissertation itself, which is not in a particularly readable form. The first article will deal with the questions, ”What was the research about? What methods of inquiry were used and what were the results?” The second article will consider, ”What can we learn from the research, i.e., what does it cause us to do?” The third article will cover what I thought about the research and what impact it had on me. Readers will observe that in addressing these three questions, I am highlighting the three fundamental dimensions of experience that philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Wilber, and Torbert have long thought are present in each and every phenomenon (whether we are aware of them or not) (see table 1).

The first question, “what is it”?, refers the to the objective third-person world of “It”–the ”What can we learn from it?”, the second-person inter-subjective world of us or “we” and the ”What do I think about it” to the first-person subjective world of “I”? Being able to see these perspectives separately while also understanding how they come together is part of the story of development. This perhaps should be a fourth article: How can we observe each of these other perspectives and see how they fit together, which would be a kind of fourth-person perspective?

|

Three-domains of Integral theory (Wilber) |

Plato’s three essences |

Aristole’s three dimensions of rhetoric |

Popper’s “Three Worlds” |

Kant’s three critiques |

Hegel’s system of science |

Habermas’ three validity claims |

Torbert’s action-inquiry |

||

|

First person |

I |

Art |

The beautiful |

Ethos |

Subjective |

Art: Critique of judgement |

Spirit/mind |

Truthfulness |

Integrity |

|

Second person |

We |

Morals |

The good |

Pathos |

Cultural |

Morals; Critique of practical reason |

Nature |

Justness or appropriate-ness |

Mutuality |

|

Third person |

It |

Science |

The true |

Logos |

Objective |

Science: Critique of pure reason |

Logic |

Objective truth |

Sustainability |

Table 1. The three domains of knowledge (first-, second-, third-person)

Another important concept that I want to highlight at the beginning of this article is the distinction between what Wilber calls the WHO x HOW x WHAT of research. The WHO in this case refers to me the researcher and to my overall altitude, level of awareness or epistemology, and how I know and interpret the research. In other words, I am the WHO that selects the HOW that interprets the WHAT and so it is not possible to speak about the validity and reliability of the study’s findings without having some indication of my underlying intentions in respect of the study. (This will be discussed in more detail in Article 3). The HOW of research refers to the subject of the research (i.e., development) and in particular to the methodology used to bring forth a developmental perspective in the research. In this case I am taking a structural approach (a zone 2 perspective in Integral Methodological Pluralism, (Kelly) which was inspired by both constructive developmental theory (Kegan) and Integral Theory (Torbert et al.; Wilber) and which I use to create a depth and span action inquiry method that is used to both estimate the developmental depth in an action as well as the integral span of other possible factors influencing that action.

The WHAT of the research is Buffett’s development. In this case, Buffett’s development is taken as an ontological given. This was clear from the existing Buffett biographies of his life (Kilpatrick; Lowenstein; O’Loughlin; Schroeder 8). Alice Schroeder remarked that Buffett’s development arose from the accumulation of a lifetime of learning and experience. Buffett’s business partner of 40 years, Charlie Munger, agreed. He described Buffett as a learning machine and as a ferocious learner (Berkshire AGM notes). So the question for my research was not, ”did Buffett develop over his life” but rather ”how did he develop”? In answering that question I wanted to distinguish between a description of his development (as provided by Schroeder and other biographers) and an analysis of development from the perspective of an existing theory of development that had nothing to do with Buffett.

You may wonder though, why do we need to understand Buffett’s development in theory? Is it not enough that we understand it in practice? The answer is that until we understand something in theory, it is very difficult to illustrate it in practice for others. As Charlie Munger notes that, it is not enough to know about the facts of something, i.e., Buffett’s development. In order for the facts to be available in a useable form, they must hang together on a “latticework of theory” (Kaufman). In other words for the facts of Buffett’s development to be available in a useable form such that they can be useful for others, they must hang together on some theory of development. That is what motivated my research; how can we understand development as a theory, what methods of inquiry can we use to evaluate development in Buffett and others and what can Buffett’s development and developmental theory in general tell us about how we may develop as well?

The WHO x HOW x WHAT of Research

| WHO? | The person conducting the research, i.e., me the researcher and my overall altitude or level of consciousness | Measured at Strategic action-logic at time of research. |

| HOW? | The subject of the research (development) and the developmental lenses used to look at the research. | Constructive-developmental theory and my action inquiry developmental method. |

| WHAT? | The object of the research (Warren Buffett’s development) | Analysing thirty-two examples from across Buffett’s life (age 14 to almost 80 yrs). |

Table 2. The WHO x HOW x WHAT of Research.

Finally, I want to introduce the notion of character and link it both to development and to leadership success. This will allow me to make the point that Buffett’s character development is at the essence of his success as a leader. Character here refers to that defining feature of being human, i.e., the capacity to stand back and observe ourselves and to act more consciously in any moment (McGilchrist; Sachs). Character is also a disposition, an inclination, or a habit. It is something we can cultivate as we grow rather than something we are endowed with to begin with. Character reminds us that we are neither slaves to our predispositions (our intelligence and temperament) nor solely dependent on our background and circumstances (our family, culture, education, society, organisation and our time in history). Our character thus stands-in-between our predispositions and our circumstances and plays an important role in determining what we apply our intelligence and temperament to and how we respond to our circumstances.

That our lives are punctuated by our developing character is as old as human culture. Ancient spiritual practices from all over the globe, Platonic philosophy, and Shakespeare’s seven ages of man all embody the idea that we can be engaged in a process of character development over our entire life span. This is also a conclusion from the Harvard Grant Study, the longest longitudinal study of human development ever undertaken, now in its seventy-fifth year. Distinguishing between personality that doesn’t change that much over our lives (McCrae) and character that does, the study concludes that, “adult development continues long after adolescence, that character is not set in plaster, and that people do change” (Vaillant). These conclusions are mirrored in this longitudinal research on Buffett. Firstly, though an introduction to the developmental constructs that motivated the research and to the depth and span action inquiry method that directed it. My role as the researcher in selecting these theories and methods and the force of my underlying intentions throughout the research will be discussed in Article 3.

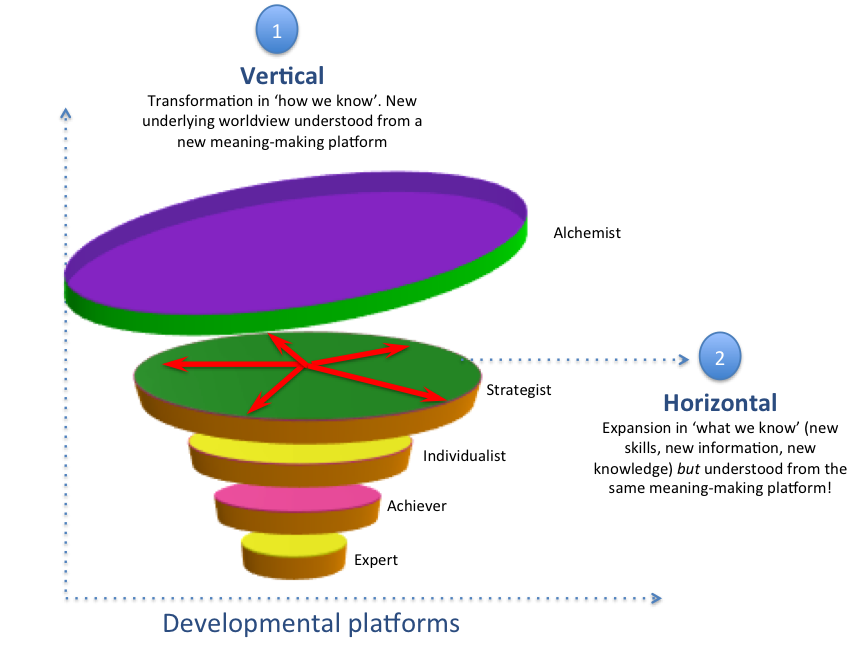

Adult Development–the Theory

There are two kinds of growth that we associate with adult development: vertical and horizontal. While both are important, they are very different. If horizontal development is concerned with content and what we know, vertical development is concerned with how we know it (Harris & Kuhnert) (see figure 1). As Cook-Greuter describes it, horizontal development is the gradual accumulation of new knowledge, new skills and experience, which can occur without any fundamental change in the individual’s overall meaning making, epistemology or worldview. Vertical development on the other hand, which is a much rarer form of development, entails a complete transformation in the individual’s meaning-making and in their overall view of reality that in turn transforms what they think, how they feel and what they do.

Figure 1. Vertical & Horizontal Development. This illustration makes the distinction between vertical and horizontal development – horizontal development being an expansion of an existing platform and vertical development being the elevation to a new platform with the new vertical platform transcending and including the old one.

Technically, ”meaning-making” here is defined within constructive-developmental theory to mean the internal organising system individuals use to make sense of their experience (Cook-Greuter; Kegan; McCauley et al.; Torbert; Wilber). This internal organising system determines what we notice and pay attention to and ultimately what actions we take. It tends however to be invisible (or unconscious to us) particularly at earlier stages of development. While we are aware of particular thoughts, feelings, and actions of our own and of others, it is much more difficult for us to become aware of the larger pattern (the action-logic) we and the teams and organizations we are participating in are generating. Indeed, one might say that the aim of character or leadership development is to become more aware of the action-logics we and others are operating through, so that we can act in more timely ways, both with regard to current effectiveness and with regard to supporting personal and business transformation toward greater sustainability.

These vertical development constructs, which are seen as relatively stable, are variously described in the literature as “stages, waves, levels, orders or altitudes of development” or as used in this study “action-logics”. Using a climbing metaphor, Cook-Greuter & Soulen (183) describe how vertical development is akin to having a higher vantage point on a mountain:

At each turn of the path up the mountain, hikers can see more of the territory they have already traversed. They can see multiple turns and reversals in the path. The climbers can see further into and across the valley. The closer they get to the summit, the easier it becomes to see behind to the shadow side and uncover formerly hidden aspects of the territory. Finally, at the top, they can see beyond their particular mountain to other ranges and further horizons. The more hikers can see, the wiser, more timely, more systematic and informed their actions and decisions are likely to be. This is so because more of the relevant information, connections, and dynamic relationships become visible.

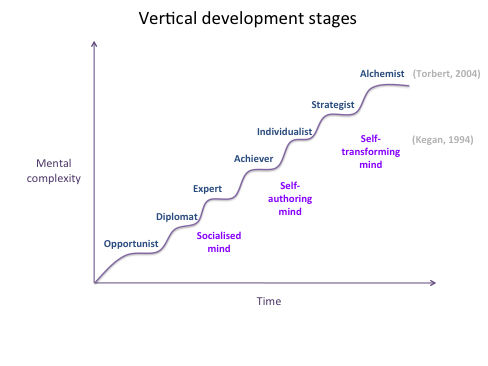

Each action-logics stage represents a centre of gravity or platform from which the individual sees the world. What they think, how they feel, and what actions they take, are therefore influenced by their centre-of-gravity that acts as their overall level of development. With each new vertical transformation what the individual was once subject to and could not see,can now be seen as object and thus be operated on. At the next action-logic stage of development, the previous assumptions, beliefs, attitudes and self-images come into view. In Torbert’s developmental theory, there are seven vertical action-logic stages of development called: Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert, Achiever, Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist which correspond with Kegan’s three later orders of consciousness known as the Socialised mind, the Self-authoring mind and the Self-transforming mind (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Vertical Stages of Growth. This illustration cross refers to two leading developmental theories; Torbert’s developmental action-logics and Kegan’s orders of consciousness. Both track the development in mental complexity and growth in consciousness and awareness over time.

Action Inquiry–the Method

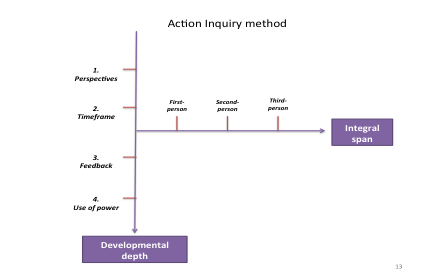

The challenge in this case with testing Buffett’s development against the predictions of developmental theory is that the existing measures of a person’s developmental action-logic (Kegan’s Subject-Object Interview, Torbert’s Global Leadership Profile, and Cook-Greuter’s Mature Adult Profile) are all measures of a person’s current action-logic, based on their open-ended responses to interview leads or sentence stems they are asked to complete. As I wanted to measure Buffett’s development retrospectively, I had to invent a new developmental method that could be consistently applied to examples from across his life. Taking inspiration from developmental theory (Cook-Greuter; Kegan) and in particular from Developmental Action Inquiry (Starr & Torbert; Torbert; Torbert & Assoc.), I chose four developmental variables–perspectives, timeframe, feedback and use of power–which can act as proxies for development, since they are said to change at each action-logic. (See Appendix 1 for more details).

Using the four developmental variables as a content free and context neutral framework to inquire into the developmental depth in Buffett’s actions, it was at least possible in theory to look at any action in any context of his life and estimate the meaning-making-in-action and then index it back to one or more of the seven developmental action-logic stages in the theory. In practice, of course, my researcher bias (the invisible hand) was never completely absent, but at least let us pretend, as we like to do in research, that we can neutralize our intentions so that we can apply an objective method to an objective set of data.

To test out whether this framework would work, I selected 32 examples of Buffett’s actions from an initial set of 74 episodes from across his lifetime, using a method to assure that the choices were not biased by me, i.e., a random selection of 30 examples from 74 examples from three different periods in his life: the early years up until he created the Buffett Partnerships in 1956, the Buffett Partnership years from 1957-1969, and the Berkshire Years from 1970 onwards. There were two later examples (examples 31 and 32) that were chosen by me to represent the elder years. Inquiring into Buffett’s actions in each of the 32 examples, I then asked the four developmental depth questions:

- What perspective(s) is Buffett operating from in this action?

- What timeframe is he aware of in his action?

- How open is he to feedback in his action? and

- How does he use his power in action?

In addition, I also considered what non-developmental factors might be influencing his actions: his pre-dispositions for instance; his intelligence and temperament; his circumstances (his family, culture, education, the shared values and leadership culture at Berkshire, his Ben Graham inspired investment method, and the market socio-economic circumstances); and his experience, skill, and knowledge (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Action Inquiry Method. This illustrates the dialectic nature of the method that acknowledges the variety of motivations, developmental and non-developmental, that may influence any action.

Each of the 32 examples in the study was subjected to the same six steps in the method. Step 1: provide a detailed description of the example. Step 2: isolate the subject’s main action–what did he actually do? Step 3: apply the four meaning-making/developmental variables: what perspective(s) is he operating from in his action, what timeframe is he aware of, how open is he to feedback and how does he use his power? Step 4: match the four variables to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory. Step 5: are there other first-, second-, or third-person factors that have impacted his action? Step 6: conclude by indicating which perspective(s) carry the most weight in his action: i.e., which are primary, secondary and contributory factors?

At the heart of the method are the four developmental variables: perspectives, time frame, feedback, and use of power within which are a number of sub-variables. For instance, there are seven different types of perspectives (first-, second-, third-, expanded third-, fourth, expanded fourth- and fifth-nth person perspectives); four different types of awareness of time (being oblivious to time or having a one-, two- or three-dimensional awareness of time); four different types of awareness of feedback (an openness to feedback that results in a change of behaviour [single-loop learning], a change in behaviour and strategy [double-loop learning] and a change in behaviour, strategy and overall vision or purpose [triple-loop learning]); and three basic types of use of power: dependent, independent and inter-independent with dependent power reflected in a coercive application of power in action, independent power in a transformational application of power and inter-independent in a mutually transforming application of power. The complete methodology is described in more detail in Chapter 3 of the dissertation under Research Methodology. There follows, however, an introduction to the four variables that is perhaps easier to follow by looking at the table in Appendix 1: The four developmental variables.

Perspectives–What Does it Mean?

The lead question is: ”What perspective is Buffett operating from that can help us better understand his meaning-making-in-action in each example”? According to developmental action-logic theory, at the Opportunist action-logic the self is subject to its own will and desire (a limited first-person perspective). At the Diplomat action-logic this shifts to a reliance on perspectives of others: peer group, family, culture or society (a second-person perspective). At the Expert action-logic the self operates from the logic of its own beliefs (a primarily third-person perspective). At the Achiever action-logic the self adds durational time to a primarily objective view of the world (third-person perspective). At the Individualist action-logic there is a noticeable separation as the self begins to explore the subjectivity behind objectivity. In the process the self sees the relative and constructed nature of reality (a fourth-person perspective). At the Strategist action-logic the self returns reinvigorated with a new post-objective-synthetic theory (an extended fourth-person perspective). Finally at the Alchemist action-logic the self begins to see the limitations of all representational maps, however integrated, where the ego becomes transparent and is seen as a limitation to further growth (a fifth-nth-person perspective).

Timeframe–What Does It Mean?

The lead question is: “What timeframe is Buffett aware of that can help us better understand his meaning-making-in-action in each example”? According to a three-dimensional theory of time, there is no temporal awareness of time in action or only a limited awareness of durational time at the Opportunist, Diplomat, and Expert action-logics. There is a one-dimensional linear awareness of durational time, past and future, at the Achiever and Individualist; a two-dimensional non-linear awareness of time one that can see the past to the future through the present at the Strategist; and a three-dimensional awareness of time– one that suspends linear and non-linear time and observes the past, the present, and the future as well as the subject actively participating in their own emergent future at the Alchemist.

Feedback–What Does It Mean?

The lead question is: “How open is Buffett to feedback that can help us better understanding his meaning-making-in-action in each example”? According to developmental theory, the earlier action-logics resist feedback, whereas the later action-logics actively invite it (Torbert). Is Buffett for instance closed to feedback in his action as associated with the Opportunist and Diplomat action-logics; open to a limited form of feedback from experts as associated with the Expert action-logic; open to feedback that results in a first-order change in behaviour (single-loop feedback) as associated with the Achiever action-logic; open to feedback that results in a second-order of change in thinking and strategy (double-loop feedback) as associated with the Individualist and Strategist action-logic? Or is he open to feedback that results in a third-order of change in overall vision or mission in life as associated with the Alchemist action-logic?

Use of Power–What Does it Mean?

The lead question is: “How does Buffett use his power that can help us better understand his meaning-making-in-action in each example”? According to developmental theory, at the Opportunist action-logic power is motivated by the individual’s needs and desires. The individual treats whatever they can get away with as legal, i.e., might is right. At the Diplomat action-logic power is motivated by defending social norms, i.e., social norms rule personal needs. At the Expert action-logic the individual’s needs and society’s norms give way to the individual’s craft-logic (their preferred third-person method or deeply held belief system), i.e., their craft-logic rules social norms. At these early action-logics, the individual’s use of power is dependent on their authority at the Opportunist, their associations at the Diplomat and their principles at the Expert. At the Achiever action-logic it shifts to a more pragmatic approach where the overall goal motivates the use of power, i.e., system effectiveness rules craft-logic. At the Individualist action-logic the individual explores, adapts and or creates new ways of operating, i.e., relativism rules systematic effectiveness of any single system. At these mid action-logics, the individual begins to use their power in action in an independent way. They begin to sense themselves as being the authors of their own power. At the later Strategist action-logic, power is motivated by a desire to optimize the interaction between people and different systems, i.e., most valuable principles rule relativism. Finally at the Alchemist action-logic power is motivated by a desire to create transforming opportunities for self and others, i.e., deep processes and inter-systemic evolution rule principles. At these later action-logics the individual begins to use their power in action in a way that not only transforms others but themselves as well. In fact it is the personal transformation of the power yielder as well as the desire to transform others and their situation that distinguishes these later action-logics. Such use of power is both “mutually independent” and “mutually dependent” (McCauley et al. 638).

The Results

Applying the above method, the study considered whether: 1) the four variables could be reliably used to estimate the developmental depth in each action, 2) whether the developmental depth could be indexed back to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory, 3) whether Buffett’s development followed the order of development predicted by the theory and 4) whether development was the only thing going on in each example. (See Figure 3 and Appendix 1 and 2 for more details).

In the case of questions 1, 2 and 3, the answer was yes. In the case of question 4, the answer was no. It was possible to consistently apply the four variables over the thirty-two examples and to estimate the developmental depth in each action. It was also possible to index the developmental depth back to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory. Also, with few exceptions, the order of development in the 32 examples followed the predicted order of development in the theory. Buffett’s development, however, wasn’t the only thing going on in each example and in some cases it wasn’t even the primary thing.

It was clear from analyzing the 32 examples that Buffett incorporated more perspectives in his actions in later as compared to earlier actions in his life. It was also clear that he expanded his timeframe, both linear time (past and future) and non-linear present time as well. There is also a noticeable increase in his openness to feedback from himself, others and the world. Finally, he changed how he used his power from an early unilateral and transactional use of power to a later more relational and transformational use of power.

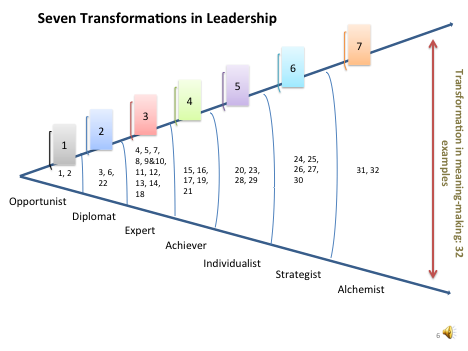

Further, it was possible to index the developmental depth in each action back to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory. For instance, of the 32 examples, there are two examples at the Opportunist action-logic (examples 1 and 2 [note that examples are numbered chronologically]). There are three examples at the Diplomat action-logic (examples 3, 6 and 22 [note that #22 is the example most unaligned with theoretical prediction]). There are 11 examples at the Expert action-logic (examples 4, 5, 7, 8, 9&10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 18), five examples at the Achiever action-logic (examples 15, 16, 17, 19 and 21), four examples at the Individualist action-logic (examples 20, 23, 28 and 29), five at the Strategist action-logic (examples 24, 25, 26, 27 and 30) and two at the Alchemist action-logic (examples 31 and 32). These are outlined in appendix 3.

As can be seen by observation (see Figure 4. Seven Transformations in Leadership), the resulting empirical order of the examples is very close to the theoretically-predicted order. Just how strong the correlation is, is demonstrated by a Spearman Rank Order Test which shows a p value of .93, accounting for 86% of the variance (social scientists regard any variable that accounts for more than 25% of the variance robust). In addition however, other first-, second- and third-person factors are also relatively important in understanding his actions in many of the examples. Thus, according to my estimates, Buffett’s developmental depth is the only primary factor in causing Buffett’s actions in five of the examples. In 21 examples, I estimate Buffett’s action-logic as equally important to non-developmental factors. And I estimate it as a secondary or contributory factor in six other examples.

Figure 4. Seven Transformations in Leadership. This illustration tracks the thirty-two examples from the study onto the seven developmental action-logics in the theory (Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert, Achiever, Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist). There are two examples at the Opportunist, three at the Diplomat, eleven at the Expert, five at the Achiever, four at the Individualist, five at the Strategist and two at the Alchemist. What is clear is that Buffett has gone through “Seven transformations in leadership” over his long career.

Implications of the Results

As seen through a vertical developmental theory and through a vertical developmental lens (both of which I chose/created because they interested me), the results indicate that Warren Buffett has gone through seven transformations of leadership over his long business career, the implications of which are that the development in his character has impacted his success as both an investor and as a leader, but more particularly as a leader. You may ask though, how valid and reliable are these conclusions and how reasonable are these implications? These are important questions to address before being able to hear the subject matter of Article 2, which is, “what can we learn from this research and what does it cause us to do”?

I address the validity and reliability question at some length in the dissertation. Suffice it to say here that the primary knowledge claims are made at the level of theory and research, and to the knowledge community within constructive-developmental and integral theory. This is because the classification of my method as a soft qualitative metric determines to some extent the level at which the knowledge claims can be made and the kind of qualitative quality control standards that apply. (For a more detailed discussion on this topic see Stein & Heikkinen: Models, Metrics and Measurement in Developmental Psychology). Even if this is the case however, this doesn’t tell us anything about the impact the study had on me (first-person) or indeed what impact it may have on you and yours should you be able to consider the results for yourself (second-person) and yet consistent with an integral epistemology, these first- and second-person perspectives need to be considered.

The results from this study are also offered within the broader field of social science (a complex world of dynamic humans, cultures, societies and organisations) and a world in which it is very difficult to nail results to any cross. As Gardner points out, the best we can hope for, using good scientific process at the third-person level, are plausible outcomes, which we test and retest for accuracy. Quoting from Carnedades of Cyrene, Douglas Walton, in his book Informal Logic says:

A proposition is plausible if it seems to be true, and (even more plausible) if it is consistent with other propositions that seem to be true, and (even more plausible) if it is tested, and passes the test (p.26).

The results of this study and the methods used can be further verified by application to other individuals in other environments. This hasn’t as yet occurred. As a result we are left with a relatively small sample of individual cases (32 examples), which were all applied to one individual. If these results were not found to be consistent with the broader theory of constructive developmental theory where there is evidence of thousands of such cases, the research may be greeted more sceptically.

Verification, however, is not the only route we can take to improve the validity and reliability of the findings. We can also improve their robustness by trying to falsify them, i.e., instead of trying to prove the study was right by repeating the study, we might try to prove the study was wrong by finding other explanations for the results. As Karl Popper would have us do, try and create conditions under which the results could be rejected. I attempted to disprove the conclusions from the study in two ways; through the dialectic nature of the method I used and through revisiting the thirty-two examples from the perspective of four alternative theories of development.

The Action Inquiry method is dialectic in that it weighs development and non-development factors equally, i.e., the method searches for and finds evidence of developmental as well as non-developmental factors influencing Buffett’s actions. There is no sense then in which Buffett’s character development is the only thing going on in his success as a leader. The reality of his leadership is much more complex than any one method of inquiry used to reveal it. Perhaps the simplest way of saying it is that the sustainability of Buffett’s leadership, at the very least, includes some combination of his human capital (his intelligence and temperament (his pre-dispositions), his social capital (his life circumstances, cumulative experience and the quality of the companies he acquires and the managers that come with them) and his character development. His character development, however, is worthy of particular attention because as noted earlier it stands between his intelligence and temperament and his circumstances and plays an important role in determining what he applies his intelligence and temperament to and how he responds to his circumstances, and as we see throughout this study, this changes and develops.

It is also the case that the developmental theory I selected (Developmental Action Inquiry, Torbert & al.) was not the only developmental theory that could be used to understand Buffett’s development. Four alternative theories were also considered; two structure-stage developmental approaches; Kegan’s Orders Of Consciousness and Levinson’s Life Cycle Theory of Adult Development and two non-structure-stage developmental approaches, Bandura’s Social Learning Theory and Scharmer’s Theory U. These were more or less helpful in understanding Buffett’s development.

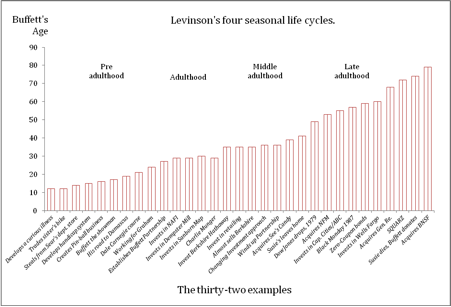

Not surprisingly perhaps, given they come from the same constructive-developmental theory stable, Kegan’s Orders of Consciousness provides a useful alternative way of looking at Buffett’s development. As we track the development in Buffett’s character and awareness through seven transformations, we can also track his development through Kegan’s three later stage orders of consciousness. Perhaps Scharmer’s Theory U could be re-constructed as a retrospective method but that is not how it is currently designed and so it is of less value in this study. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory helps to highlight the importance of culture and circumstance and its impact on behaviour-in- action, but it omits the agency factor associated with each individual. Also, the importance of Buffett’s family background, culture and socio-economic circumstances are already captured in the dialectic nature of the action inquiry method used. Levinson’s Seasonal Life Cycle Theory was not expected by the author to reveal much about Buffett’s development but that proved not to be the case. As illustrated in figure 5., when Buffett’s age is linked to his action-logic in each example and then overlaid on Levinson’s four seasonal life cycles (pre-adulthood, adulthood, middle adulthood and late adulthood) there appears to be a correlation between the transformation in Buffett’s meaning making and his age/stage in life. This in part confirms the assumption in developmental theory, that age is necessary but not sufficient for development.

Figure 5. Levinson’s Seasonal Life Cycles. This illustration shows that, as might be expected, Buffett’s meaning making expands with his age and experience. It is also in line with the conclusions from the Harvard Grant study. From a developmental theory perspective, age is considered necessary but not sufficient for development. One needs time to develop but it doesn’t mean one will develop.

These efforts at falsification, however, do not make the conclusions go away. The use of the dialectic method merely highlights the relative importance of Buffett’s development depth in his actions and the comparison to other developmental theories merely re-enforces the appropriateness of the developmental theory and methods that were used. The robustness of the findings, therefore, cause us to reflect on what it means for the rest of us? For instance, ”to what extent do the findings link with other research in the field of adult development and leadership development and what implications does that have”? More specifically perhaps, if Warren Buffett’s character has developed over his life (as the biographies had already shown) and that his development has gone through seven transformations in leadership (as this research has shown) then what does the theory of development have to say about how we might develop as well, in whatever leadership circumstances we find ourselves; as a parent, a teacher, a community worker or workplace manager? Kegan & Lahey note that leadership development tends to focus on leadership and ignores development and yet it is clear from this study and others that the kinds of competencies and attributes we associate with sustainable leadership only emerge with development (Brown; Eigel; Rooke & Torbert; Weick). And so, in aligning the findings from this study with others in the field and contemplating the topic of Article 2, what has development or character development got to tell us about leadership development and what does it cause us to do?

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. General Learning Press.

Brown, B. (2011). Conscious Leadership for Sustainability: How leaders with late-stage action logic design and engage in sustainable initiatives. A Ph.D. dissertation submitted to Fielding Graduate University.

Buffett, W. (1977-2012). Buffett’s Letters to Shareholders included in the Berkshire Hathaway annual report available at www.berkshirehathaway.com.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2000). Mature ego development: A gateway to ego transcendence? Journal of Adult Development, 7(4).

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2004). Making the case for a developmental perspective. Industrial and Commercial Training, 36(6/7), 275.

Cook-Greuter, S. (2005). Ego Development: Nine Levels of Increasing Embrace. Adapted and expanded from S. Cook-Greuter (1985) A Detailed Description of the successive stages of ego-development. Unpublished manuscript Eigel, K. M. (1998). Leader effectiveness: A constructive developmental view and investigation. Dissertation Abstracts International, 59, 06B. (UMI No. 9836315).

Cook-Greuter, S. R., & Soulen, J. (2007). The developmental perspective in integral counselling. Counselling and Values, 51(3), 180-192.

Eigel, K. M. (1998). Leader effectiveness: A constructive developmental view and investigation. Dissertation Abstracts International, 59, 06B. (UMI No. 9836315).

Gad, S. (2007). Study visit to Berkshire Hathaway by MBA students from Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. Downloaded from http://www.intelligentinvestorclub.com/downloads/Warren-Buffett-University-Georgia.pdf

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

Harris, L., & Kuhnert, K., (2008). Looking through the lens of leadership: a constructive developmental approach. Leadership & Organization, Development Journal, Vol. 29 No. 1, 2008, pp. 47-67

Kegan, R. (1980). Making meaning: The constructive-developmental approach to persons and practice. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 58, 373 −380.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. & Lahey, L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Press.

Kelly, E. J (2008). An Integral Approach to the Buffett Phenomenon. A Proposed Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice Summer 2008, Vol. 3, No. 2.

Kelly, E. J (2011). Exercising Leadership Power; Warren Buffett and the integration of Integrity, Mutuality and Sustainability. In D. Weir & N. Sultan, From Critique to Action: The Practical Ethics of the Organizational World. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; New edition (1 April).

Kilpatrick, A. (2004). Of Permanent Value: the story of Warren Buffett. AKPE, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Levinson, D. J., Darrow, C. N, & Klein, E. B. (1978). Seasons of a man’s life. New York: Representative House.

Lowenstein, R. (1997). Buffett: The making of an American capitalist (2nd ed.). London: Orion Books.

Kaufman, P. (2005). Poor Charlie’s Almanack. The Donning Company Publishers, 184 Business Park Drive, Suite 206, Virginia Beach, VA 23462.

McCauley, C., Drath, W., Paulus, C., O’Connor, P., & Baker, B. (2006). The use of constructive-developmental theory to advance the understanding of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 634-653.

McCrae, R. (2002). The Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Cultures (International and Cultural Psychology). Springer; 2002 edition (August 29, 2002).

McGilchrist, I. (2010). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press; Reprint edition.

O’Loughlin, J. (2002). The Real Warren Buffett. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London, UK.

Rawls, J. (1973). A theory of justice. London: Oxford University Press.

Rooke D. & Torbert W. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s developmental stage. Organization Development Journal, 16, 11-28.

Sachs, J. (2011). The Great Partnership. God, science and search for meaning. Hodder & Stoughton (23 Jun 2011).

Scharmer, O. (2007). Theory U. The Society for Organizational Learning, Cambridge MA.

Schroeder, A (2008). The Snowball. Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. Bantam Books, September 2008.

Starr, A. & Torbert, B., (2005). Timely and Transforming Leadership Inquiry and Action: Towards Triple-loop Awareness. Integral Review 1.

Stein, Z & Heikkinen, K. (2009). Models, Metrics, and Measurement in Developmental Psychology. Integral Review. June 2009. Vol. 5, No. 1.

Torbert, W. (1976). On the possibility of revolution within the boundaries of propriety. Humanitas. 12, 1, 111-148.

Torbert, W. R. (1987). Managing the corporate dream: Restructuring for long-term success. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Torbert, W. R. (1991). The power of balance: Transforming self, society, and scientific inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Torbert, W. R., Cook-Greuter, S. R., Fisher, D., Foldy, E., Gauthier, A., Keeley, J., et al. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transformational leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Vaillant, G. (2012). Triumphs of Experience. Harvard University Press (23 Oct 2012)

Walton, D (2001). Informal Logic: Vol. 21, No. 2 (2001): pp. 141-169. Cambridge University Press.

Weick, K. (1998). Improvisation as a mindset for organizational analysis. Organization Science, 9, 543-555.

Whyte, K. (2007). Interview with Warren Buffett. Downloaded Dec 2012 http://www.macleans.ca/business/economy/article.jsp?content=20071015_110163_110163&page=1

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality. Boston: Shambhala.

Appendix 1. The Four Developmental Variables

Seven Action-Logics |

1. Perspectives

|

2. Timeframe

|

3. Feedback |

4. Power |

| Opportunist | Self is operating from its own will and desires (first-person perspective). | Weeks to months.(No conscious awareness of time) | Not open to feedback. Feedback seen as an ‘attack or threat’. Externalises blame. | Coercive, unilateral-power and the morality of authority (might makes right). Power motivated by own needs (dependent). |

| Diplomat | Self is operating form second-person perspective of others; peer group, family, culture or religion. | Months to 1 year.(No conscious awareness of time) | Not open to feedback.Receives feedback as criticism or ‘disapproval’ | Diplomatic-power and the morality of association (thy will not mine). Social norms rule personal needs (dependent). |

| Expert | Self is immersed in the logic of their own belief system. A primarily third-person perspective. | 1-2 years.(Beginning conscious awareness of durational time) | Open to feedback from Experts in the field of their primary interest. | Logistical-power and the morality of principle (the system is right). Craft-logic rules social norms (dependent) |

| Achiever | Self is operating from an expanded third-person perspective. Sees itself & others in linear time, past to future. Effective and results orientated. | 2-5 yearsConsciously thinks about linear time – a one-dimensional linear awareness (past to future). | Pragmatic. Open to feedback if it helps achieve goals. A kind of single-loop feedback that leads to first-order change in behaviour. | Systematic-productive power and the morality of ‘authority, association and principle’. Makes goal orientated contractual/pragmatic agreements. System effectiveness rules Craft-Logic (independent) |

| Individualist | Self is operating from a fourth-person perspective, one that turns inwards & sees the “myth of objective reality”, the subjectivity behind objectivity. Meaning is relative & constructed. | 5-10 years.Emerging awareness of here and now (present time) as well as longer term durational time (past and future). | Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of own behaviour. | Visionary-power. Concerned with balancing earlier forms of Coercive, Diplomatic, Logistical and Systematic power. Adapt, create, explore new rules were appropriate. Relativism rules Systematic effectiveness of any single system (independent) |

| Strategist | Self is operating from an expanded fourth-person perspective. Relative & constructed gives ways to a new “post-objective-synthetic integrated theory”. | 10-20 yearsA two-dimensional awareness of time (adds awareness of present time to thinking in durational time, past to future). | Invites feedback for self-actualisation.A kind of Double-loop feedback which can lead to second-order change in behaviour & strategy (thinking). | Praxis-power. Power directed outwards towards optimizing interaction of people and systems. Concerned with reframing, reinterpreting situation so that decisions support overall principle. Most valuable principles rule relativism (inter-independent). |

| Alchemist | Self is operating from a fifth to nth-person perspective. Sees the limits of all representational maps, including integrated ones. Ego becomes transparent & a limit to further growth. May access a ‘direct mode of knowing’. | Up to 100 years (multi-generational).A three-dimensional awareness of time (durational time, non-durational present time, seeing oneself living in the present among others intentionally influencing one anothers’ futures’). | Views feedback as a natural part of living systems. Open to a kind of Triple-loop feedback which can lead to a third-order change in behaviour, strategy and overall goal or mission which changes and dissolves into a sense of connectedness to ‘whole’. | Mutually-transforming power. Creating transformational opportunities for self and others. Deep processes and inter-systemic evolution rule principles (inter-independent). |

Note: Adapted and created from: Cook-Greuter, (2005), Fisher, Rooke & Torbert, (2003); Harthill, (2008), Torbert & Ass., (2004); McCauley et al. (2006)

Appendix 2. The Six Steps in the Action Inquiry Method

(Taken directly from my thesis)

Each of the 32 examples from across Buffett’s life is subjected to the same six steps in the meaning-making-in-action method. Step 1: provide a detailed description of the example. Step 2: isolate the subject’s main action–what did he actually do? Step 3: apply the four meaning-making/developmental variables; what perspective(s) is he operating from in his action? What timeframe is he aware of? How open is he to feedback? And how does he use his power? Step 4: match the four variables to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory. Step 5: are there other first-, second-, or third-person factors that have impacted his action? Step 6: conclude by indicating which perspective(s) carry the most weight in his action; i.e., which are primary, secondary, and contributory factors? The six steps are discussed in more detail as follows:

Step 1: provide a detailed description of the example. This step provides a rich and detailed description of the action in each of the 32 examples, i.e., what actually happened. Each description can be up to an A4 page in length. As discussed above (see section on the Representative Distribution of the 32 examples), having selected the examples from the earlier Biographical Sketch of Buffett’s life, additional material was also added from Schroeder’s later biography of Buffett.

Step 2: isolate the subject’s main action. While this is a necessary step it has the effect of removing the action from its context. Is this a problem? Context here forms part of the content of the action, which is important in any comprehensive understanding of what happened and is re-introduced in step 5. It is not however necessary for a meaning-making-in-action analysis. According to the theory, the self-system of the individual is ”content free and context neutral” (McCauley et al.). In other words in theory it should be possible to look at any action in any context and estimate the meaning-making-in-action by applying the four variables, perspectives, timeframe, feedback, and use of power.

Step 3: apply the four meaning-making variables; what perspective(s) is he operating from in his action? What timeframe is he aware of? How open is he to feedback? And how does he use his power? This step, along with step 4, goes to the heart of the method. Having isolated the action, this step examines the action through the lens of the four developmental variables, perspective(s), timeframe, feedback and use of power and then bootstraps them back to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory (See also earlier introduction to meaning-making and developmental action-logic theory).

Step 4: match the four variables to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in the theory? i.e., to what extent do the four meaning-making variables match with anyone or more of the seven action-logics? This is the bootstrapping process referred to earlier where the description of the each of the four variables in the action is matched to one or more of the seven developmental action-logics in developmental theory.

Step 5: are there other first-, second- and third-person factors that have impacted the subject’s action? Whereas in steps 3 and 4 the focus is on meaning-making-in-action as a framework, step 5 considers other content factors that may have influenced Buffett’s behaviour-in-action. First-person factors might include Buffett’s intelligence and temperament, motivation and creativity, his competency and personality, second-person factors such as the role of significant others in his life and the shared values and leadership culture that Buffett created at Berkshire and third-person factors such as Buffett’s investment method and the external socio-economic circumstances he found himself in over the past 50 years.

Step 6: conclude by indicating which perspective(s) carry the most weight in his action, i.e., which are primary, secondary, and contributory factors? This is an important step, which as noted earlier, highlights the complexity of factors influencing Buffett’s behaviour-in-action while also establishing the relative importance of his meaning-making. As discussed in the research findings section, while Buffett’s meaning-making was important in nearly all the 32 examples, it was not the only factor or the most important factor in some.

Appendix 3. The Thirty-Two Examples from Buffett’s Life.

|

RANDOM SELECTION FROM 76 EXAMPLES |

E.G., NO |

HEADINGS |

YEAR |

BUFFETT’S AGE (approx) |

BUFFETT’S ACTION |

DEVELOP-MENTAL DEPTH |

|

1 |

1 |

Curious illness |

1942 |

12 |

Develops a curious illness | Opportunist |

|

2 |

2 |

Selling his sisters’ bike |

1943 |

13 |

Buffett sells his sisters bike without telling her | Opportunist |

|

6 |

3 |

Stealing from Sears |

1945 |

15 |

Buffett steals from Sears dept store | Diplomat |

|

7 |

4 |

Betting on horses |

1943-1946 |

13-16 |

Buffett develops a handicap system | Expert |

|

9 |

5 |

Pin-Ball business |

1946-47 |

16-17 |

Buffett rents out pin-ball machines to barbershops with his partner Don Danly | Expert |

|

12 |

6 |

Buffett the showman |

1947 |

17 |

Buffett organises a number of ‘attention seeking’ stunts | Diplomat |

|

13 |

7 |

Buffett’s “road to Damascus” |

1949 |

19 |

Buffett reads the Intelligent Investor | Expert |

|

15 |

8 |

Dale Carnegie Course in public speaking |

1951 |

21 |

Buffet takes a night course in public speaking | Expert |

|

20 |

9&10 |

Working for Graham-Newman |

1954 |

24 |

Buffett goes to work for Ben Graham and Graham-Newman on Wall St | Expert |

|

23 |

11 |

Buffett establishes the Buffett partnership |

1956 |

26 |

Buffett starts his own partnership on the lines of Graham-Newman. He is the only employee | Expert |

|

25 |

12 |

Investment in National Fire Insurance (NAFI) |

1957 |

27 |

Buffett sees an opportunity and send his lawyer around Nebraska buying up shares from farmers | Expert |

|

27 |

13 |

Invests in Dempster Mill |

1956 |

26 |

Buffett finds an undervalued stock using his powerful investment method | Expert |

|

28 |

14 |

Invests in Sanborn Map |

1958 |

28 |

Buffett finds an undervalued stock using his powerful investment method | Expert |

|

29 |

15 |

Buffett meets Charlie Munger |

1959 |

29 |

Buffett finds a confidant and alter-ego | Achiever |

|

30 |

16 |

Invests in Berkshire |

1962 |

32 |

Buffett finds another undervalued stock using his powerful investment method | Achiever |

|

34 |

17 |

Invests in Hochschild & Co |

1967 |

37 |

Buffett invests in retailing | Achiever |

|

35 |

18 |

Buffett nearly sells his interest in Berkshire |

1962-64 |

32-24 |

Buffett nearly sells his interest in Berkshire | Expert |

|

41 |

19 |

Buffett’s changing investment style |

1969 |

39 |

Buffett develops a new investment approach – quantitative and qualitative | Achiever |

|

42 |

20 |

Winds up the partnership |

1969 |

39 |

Buffett says “he did not want to ruin a good record playing a game he did not understand” | Individualist |

|

46 |

21 |

See’s Candy |

1971 |

41 |

Buffett & others acquire ownership of See’s Candy | Achiever |

|

52 |

22 |

Susie moves out |

1977 |

47 |

Buffett devastated | Diplomat |

|

54 |

23 |

Dow Jones drops |

1979 |

49 |

Buffett back in the market | Individualist |

|

55 |

24 |

Nebraska Furniture Market |

1983 |

53 |

Buffett’s largest acquisition to date – ‘focuses on competitive advantage” | Strategist |

|

56 |

25 |

Capital Cities |

1985 |

55 |

Buffett’s buys ‘management’ and ‘competitive advantage’ | Strategist |

|

59 |

26 |

Black Monday |

1987 |

57 |

Buffett already out of the market 6 months earlier | Strategist |

|

64 |

27 |

Buffett issues Zero-Coupon Bonds |

1989 |

59 |

Buffett issues €400m zero coupon bonds? | Strategist |

|

65 |

28 |

Wells Fargo |

1990 |

60 |

Property market in decline, Buffett buys into a Bank | Individualist |

|

72 |

29 |

Gen Re |

1998 |

68 |

Buffett’s largest investment by far, $22 billion | Individualist |

|

74 |

30 |

SQUARZ |

2002 |

72 |

Buffett is paid to receive money – highly unusual | Strategist |

|

75 |

31 |

Susie’s death & donating his fortune |

2004-2006 |

74-76 |

Buffett donates largest ever gift of its kind | Alchemist |

|

76 |

32 |

Burlington National Santa Fe |

2009 |

79 |

Buffett buys BNSF for $33 billion his largest deal ever | Alchemist |

About the Author

Edward J. Kelly (BA, MBA, Ph.D) is aged 53 and lives in Dublin Ireland. Over the years he has been an adventurer, a businessman and a researcher. As an adventurer, he entered the Guinness Book of Records in 1990 having organised and participated in the longest most expensive taxi ride in history from London to Sydney. As a businessman he founded and managed his own company in the telecoms sector and as a researcher (last eight years) he has explored various approaches to leadership development and completed a PhD on one of the world’s most successful investors and business leaders, Warren Buffett. He now works as a facilitator helping individuals, teams and organisations transform themselves, their networks and their businesses.