Kirstin McGuire

The depth and breadth of unrealized human potential currently lying dormant in our Eco is more than a match for any personal, local, societal, global, economical or ecological problem we face. The full actualization of these potentials through constructing a creative and transformative educational and leadership effort is our opportunity. (McCaslin, 2013, p. 7)

Breathing Life Back into Creativity at Work

Despite billions of dollars and countless hours invested in talent development, businesses still struggle with unlocking the creative potential of employees. The result? Innovation has suffered and employees have disengaged from their work.

Creativity is deeply undervalued in America today outside of a tiny few university and business enclaves. Only 9% of all public and private companies do any sort of innovation. Our best schools teach the tools of efficiency and analysis. Yet we know that creativity increasingly is the greatest value-generator. (Nussbaum, 2013, p. 1)

Creativity is the lifeblood of healthy companies and healthy employees. Resuscitating our capacity for creative expression at work requires a conscious shift in how we think about what creativity is, where it comes from, who has it and how to evoke it. The good news is that creativity exists in abundance in every human being on the planet (Cameron, 1992; Harmon & Rheingold, 1984; Rogers, 1961). The bad news is that actions taken by business people within the workplace often undermine the factors that support and evoke creativity (Amabile, 1999). At the heart of creative expression is vulnerability, which is often at odds with the pressure of a competitive, results-driven work environment. People tend to protect and hide their creativity to avoid making mistakes or looking bad in front of leaders and peers (Brown, 2012).

I begin by posing a provocative question for leaders. Instead of the relentless pursuit of productivity and performance, what if we focused on designing an environment conducive to creativity and let productivity be the result instead of the driver? Doing more with less—the overused mantra of productivity and efficiency—has sucked the life out of employee creativity. We have squeezed out just about all we can get from employees by focusing on cutting costs, being more productive and efficient, and making the quarterly numbers. In the process, we have also suffocated joy and creativity, leaving employees feeling spent and disengaged.

There is nothing wrong with wanting to increase productivity and performance. They are important factors in business success. However, pushing for higher and higher levels of productivity and efficiency or driving for ever-increasing financials isn’t what inspires employees to go the extra mile or to dig deep to access their innate creative capacities for the good of the business.

What if a radical yet simple change in focus from productivity to creativity sparked the passion, engagement, and creative expression of employees, and unlocked the massive pool of unrealized potential for innovation and performance that already exists in our human resources? We are innately creative beings with the built-in drive to express our unique creative potential. By recognizing and aligning our innate creative strengths with our professional work, our ability to contribute expands. As leaders and managers of people, if we can help each of our employees tap into their creative potential and support them with an environment where they are encouraged, recognized and feel safe to express their strengths, we can begin to access the creativity that lies dormant within our organizations.

Due to their relationship with employees, managers are key to unlocking the creative potential of our human resources. They have a direct influence on whether that untapped potential becomes organizational capacity for performance or remains unexpressed, suffocated under the weight of doing more with less. It may seem obvious that the manager’s role should be to develop employees, create engagement, and generate innovative ideas, but the reality is that most managers are unaware of the factors that create or undermine creativity, let alone their role in cultivating it in their employees (Amabile & Kramer, 2007). Not only that, managers are held accountable for getting the work done, which is not the same as being responsible for recognizing and developing employee potential.

There is a gap between the competencies managers are expected to have with regard to employee development, engagement and creativity and their actual ability to put those competencies into practice and drive positive results. “Sometimes, organizations have elegant ‘manager competency’ models, but managers still don’t understand what they actually need to do to meet expectations” (Baumruk & Gorman, 2006, p. 27).

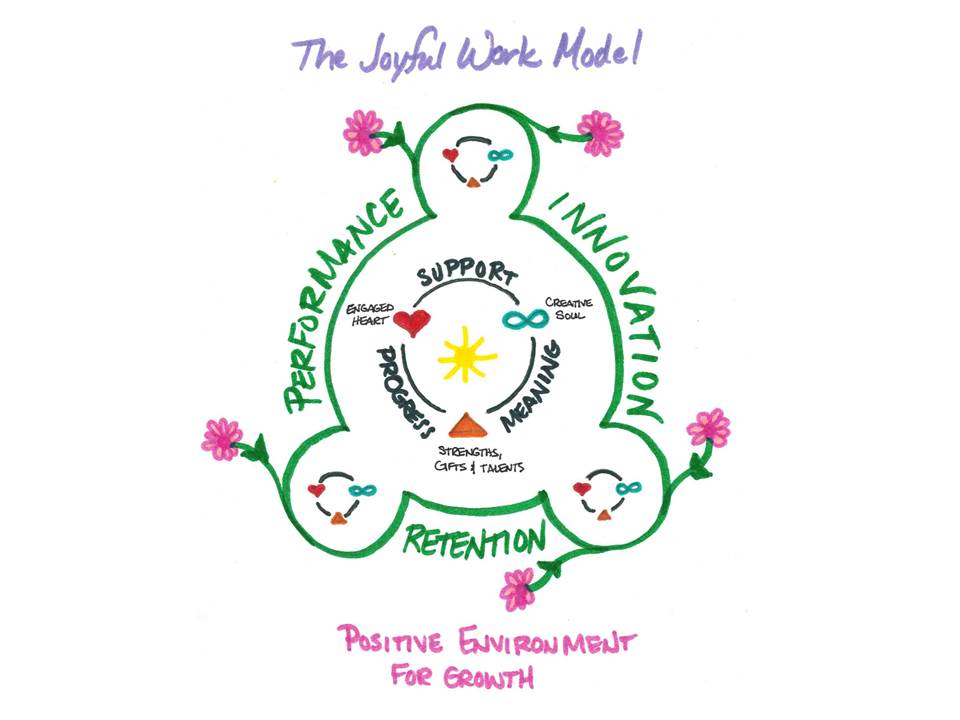

This article will explore the building blocks for greater employee engagement and creativity through an original concept I have developed called The Joyful Work Model™. I propose that by recognizing and aligning to the unique gifts and strengths of the people in our organizations and creating the environment and opportunities for creative expression, we will be able to generate a new level of business innovation and performance fueled by the passion and realized potential of our human resources. Because managers can directly impact these factors, I also invite organizational leaders to adopt a new vision that re-imagines the higher purpose of managers and equips them to step up to their role as the cultivators of creative potential.

The Joyful Work Model

“Joyful Work” describes the joy people experience from feeling purposeful and engaged doing work that is in alignment with their innate creative strengths, defined here as those gifts and talents that spark genuine interest, passion, and motivation, which is different from things we may be good at, but do not enjoy doing. Joyful Work does not mean that people will always feel joyful about their jobs, but instead that on a very consistent basis, they feel good about the jobs they are doing, have positive feelings for the company they work for and the people they work with, and are intrinsically motivated to “go the extra mile” to get the job done. Not only are they empowered in their work, they are also embodying their potential.

The Joyful Work Model, shown in Figure 1 below, illustrates the connection between individual engagement, creative expression, and joy, and how this can be supported in a professional capacity to generate positive outcomes for both the individual and organization.

Figure 1. The Joyful Work Model™

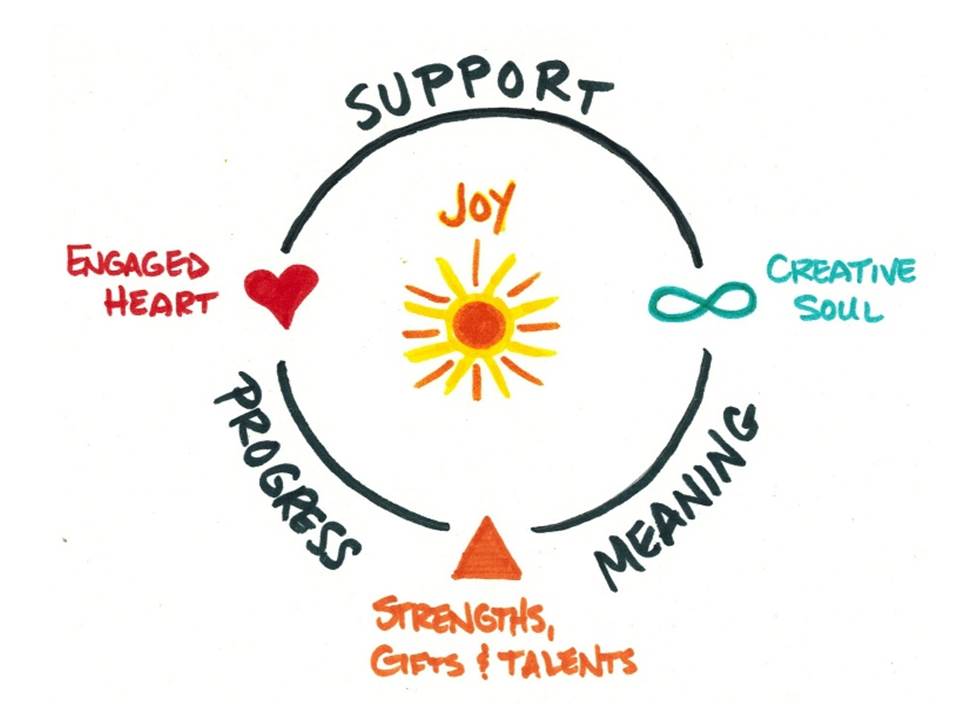

Our natural pull in life is to grow and achieve our highest potential (Maslow, 1954). At the center of The Joyful Work Model is an individual with unique strengths, gifts, and talents. With the opportunity to use these strengths, the individual becomes more engaged—“my heart is in it.” In this engaged state and in combination with using core strengths, one becomes aligned to her soul’s innate creative potential. Feelings of joy are generated from the expression of this creative potential, and self-actualizing growth occurs (Rogers, 1961).

If we view the model from the outside as a leader wanting to more fully leverage the organization’s human resources for innovation and performance, when we do the work to engage the heart, we can move to the next level, which involves actively engaging the soul through creative expression. The more we create alignment between the individual’s self-actualizing cycle and the work, the better the outcomes we create for both the organization (performance, innovation and retention) and the individual (joy, satisfaction, accomplishment and engagement).

Why do I talk about engaging hearts and souls instead of hearts and minds, which is a commonly used phrase in corporate engagement strategies? The Joyful Work Model is underpinned by the philosophy that the essence of every human is innately creative and yearns to be expressed through the gifts and talents that are unique to each individual. This is our soul, and our purpose is to bring to fruition the full potential of the creative capacity that flows from here.

It is not that we do not engage minds; it is that we need the soul engaged as well to unleash the synergy that emerges from aligning our thoughts and actions with our unique creative capacity. When we embody a rich integration of mind, soul, and heart, our creativity is nourished and our imagination comes alive.

The building blocks for engaging the hearts and souls of people through their work are:

- Strengths: We need to deeply understand and value the innate strengths, gifts, and talents of each individual.

- Meaning: We need to find what employees care about and match them to meaningful work that puts their strengths to good use, is appropriately challenging, and is valued.

- Support: We need to actively support employees by giving them enough time and resources to do the job, recognizing their efforts, providing guidance, and granting them autonomy.

- Progress: We need to make sure they are able to achieve progress on a daily basis with minimal blocks and setbacks.

- Connection: We need to help people feel like they belong and help them make the connection between their contributions and something bigger. We need to show them how their role adds value in combination with others in the working community.

- Positive environment for growth: We must create a positive environment for growth that is conscious, empathic, and potentiating. It is imperative to remove toxicities including dysfunctional competition, backstabbing, politicking, ethical issues, dishonesty, and unproductive criticism. We need to teach integrity, empathic communication, good will, collaboration, compassion, courtesy, and kindness through our own actions.

These building blocks of Joyful Work lay the foundation for employee engagement and creative expression. Without these fundamental elements, people are just biding their time until something better comes along. Until their job becomes a joy, people will not be willing to put their heart and soul into it.

Managers: The Imaginers of Potential

Managers are a vital catalyst in creating Joyful Work. The traditional model of management in use today places tremendous pressure on managers, especially in the middle-to-lower levels (CIPD, 2012). Not only are they accountable for producing business results, they are also expected to be effective people managers, as well. In reality, managers are only held accountable for their output and the output of their teams, not whether they are nurturing and growing their employees’ potential.

As long as organizations define managers’ work as being individually accountable for producing specific outputs themselves, there’ll be problems. The definition of managers’ work needs to include the development and performance levels of their staff. Organizations need to say that managers will be assessed on how their people grow, perform and advance in their careers. (Baumruk & Gorman, 2006, p. 26)

I have personally experienced the soul-crushing effect of what happens when a talented individual contributor is promoted and becomes a manager who focuses on output, but does not understand her impact on the team’s motivation, engagement, and creativity. In the pursuit of perfect outputs and productivity, this manager did not recognize that her higher purpose was to draw out the talent and creativity of her team. Instead, she worked to mold the team to her vision of perfection, rather than seek to understand and embrace their unique nature and gifts. Her fear of losing control of the outcome caused her to micromanage, criticize, and disempower her employees.

As a direct report to this manager, I experienced a lack of support, frequent harsh criticism, and roadblocks to progress. Eventually, I began to lose confidence in my abilities and started to second-guess myself. I had to emotionally disengage in order to survive what I felt was an attack on my integrity and contribution. It was nearly impossible to summon my creativity because I felt that my individual gifts and strengths were not valued. It was only her vision that was “right”. There was no room for co-creation, and though I tried hard to hold on to my creativity, it was less painful to just fall in line.

In psychological terms, the lack of empathic response to my authentic contribution caused the creation of a false self in order to survive the rejection (Firman & Gila, 2002). When this happens, both the creativity and the pain are repressed. This kind of wounding and repression is common in business, resulting in a chronic disconnection with the source of individual creativity—the soul. This is definitely not an effective strategy for improving creativity and innovation.

The pain of disengagement, micromanagement, and constant criticism became too much for my heart and soul to endure. I quit that job, even though I felt the work was in alignment with my true creative purpose. The irony of the situation is that this manager often touted the values of teamwork, yet her actions evoked disengagement and fear, two significant killers of creativity.

I tell this story to illustrate how incredibly important the relationship between manager and employee is to both engagement and creativity. Based on hearing similar stories from many people, we can be sure that these scenarios are playing out in workplaces across the globe on a daily basis. Companies can spend all the money in the world to survey employees and come up with ideas for improvement, but without an empowering relationship at the manager-employee level, corporate investments will largely be wasted.

As such, I invite business leaders, managers, stakeholders, and employees to re-imagine the role and purpose of those who manage our precious and valuable human resources. Consider what would be possible if Managers of output became Imaginers of potential. Imaginers:

- Hold themselves accountable for unlocking the potential of each employee under

their stewardship. - Come to work every day motivated to help their employees find and use their innate talents and creativity in meaningful ways that support the goals of the organization.

- Empower people and help them move through blocks to make progress.

- Recognize people and celebrate wins, small and big.

- Value diversity, and create a sense of belonging and community founded on the unique strengths of each person on the team.

- Are present, open, and listen deeply.

- Are conscious of their impact on the people they work with and strive to be creative in their interactions, as opposed to being destructive.

- Embrace creativity and are role models for it.

- Build a positive environment in which employees can thrive and feel safe to be vulnerable and share creative ideas.

- Never assume they know the answers.

- Always ask what is possible.

Imaginers understand the value of their role in shaping individual employee experience and nurturing potential, day in and day out, and prioritize their engagement activities with as much, or more, importance as other tasks. In my opinion, this is the manager’s higher purpose; as such, they need to make sustainable engagement and creativity a practice they focus on, make time for, and schedule first. They must set a conscious intention to conduct themselves as Imaginers of potential rather than Managers of output.

Engaging Hearts

The first order of business for liberating creativity is to engage hearts. Traditional texts on the subject call this employee engagement, “the emotional commitment the employee has to the organization and its goals,” (Kruse, 2012, June, p. 1) resulting in the use of discretionary effort. In other words, it is how far the employee is willing to go to get the job done. There are at least 28 research studies proving the benefits of employee engagement with correlations across a multitude of areas including service, sales, quality, safety, retention, profit, and total shareholder return (Kruse, 2012, September). With that kind of hard evidence, it is no wonder businesses are eager to find ways to boost engagement.

Despite efforts by employers to improve employee engagement, 89% of workers are not engaged and of those, 62% are emotionally detached and likely to be doing little more than necessary to keep their jobs; 27% are actively disengaged (Gallup, 2010). The cost of disengagement is estimated at a staggering $300 billion annually, just in the United States (Amabile, 2011a). This is a huge dilemma for leaders who want their businesses to be more innovative and to drive better performance.

Results from the Towers Watson (2012) Global Workforce Study show that the traditional definition of engagement, the willingness to invest discretionary effort on the job, is no longer sufficient to drive top performance. The conclusions of the study suggest businesses need to adopt a wider approach to sustainable engagement driven by cultural and relational aspects of the work experience that generates a more supportive and energizing work environment.

Schwartz (2012) writes, “For organizations, the challenge is to shift from their traditional focus on getting more out of people, to investing in meeting people’s core needs so they’re freed, fueled, and inspired to bring more of themselves to work, more sustainably” (p. 1). Imaginers in creative synergy with The Joyful Work Model can address this call for something deeper by promoting the active discovery and use of innate strengths to align employees to meaningful work and supporting them so they can make consistent progress. Employees will feel they belong to a community and are empowered in the co-creation of a healthy, inspired environment. Joyful Work spills over to Joyful Home and inspires positivity well beyond the workplace.

Engaging the hearts of employees pays off with big results for businesses. The Towers Watson (2012) study found that companies with the highest sustainable engagement scores had an average one-year operating margin of 27% compared to 14% for companies with high traditional engagement scores.

Three Practices for Managers to Engage the Hearts of Their Employees

There are many things managers can do to support their employees’ pursuit of Joyful Work, as well as their own. I have found three foundational practices that are particularly helpful to engage the hearts of employees:

- Be present with people

- Get to know people

- Help people make progress

Be present with people. Nothing is more disengaging than being with another person who is distracted. This can be expressed in a multitude of ways, including being physically distracted by technology (phones, email), other people or other happenings in the surroundings, or being mentally distracted by thoughts of anything other than the topic and person at hand.

Work is a highly distracting environment. According to the Towers Watson (2012) study, only 21% of disengaged employees agreed that their manager had time to handle the people aspects of their job. There is always something or someone vying for attention. However, if managers aspire to create a sense of engagement and support, they must learn to become fully present with the members of their teams both in one-on-one and group settings. First, managers are teaching through their leadership. They are role modeling the behavior they expect their teams to carry forward in their interactions with others. Second, they are sending a message about the priority of that person or team. When a manager sits behind a desk during a meeting with an employee and repeatedly glances at the computer screen or smart phone, the manager is communicating that whatever is on that screen is more important than the person sitting there.

Presence is a practice that must be cultivated minute by minute. Without it, managers will have a difficult time engaging employees.

Get to know people. Managers who are oriented toward recognizing employees’ natural strengths, creative potential, and skills can use such potential to increase creative output (Castro, Gomes, & de Sousa, 2012). That involves getting to know people through both communication and observation. It means getting past status updates and asking meaningful questions, having a two-way dialogue, and listening deeply to what is communicated. It also means getting input from others and paying close attention to how people handle the work assigned to them. It is a process, not a checklist. It takes time to uncover motivations and strengths, but this is a cornerstone of engagement and creativity.

Gallup research on leadership finds that the most effective leaders are always investing in strengths. In the workplace where leadership fails to focus on an individual’s strengths, the odds of the employee being engaged are 9% versus 73% when leadership does focus on the strengths of employees (Rath & Conchie, 2008).

Managers should realize that people grow the most in areas of their greatest strengths and they cannot turn weaknesses into strengths (Buckingham, 2008). It is a mistake to believe that a manager’s job is to “mold, or transform, each employee into the perfect vision of the role” (Buckingham, 2005, p. 79). It is not about shaping the person to the role; it is about discovering the person’s unique strengths and capitalizing on those within the role.

Most people want to do well at work, contribute, and be recognized. Helping people become aware of their strengths and providing opportunities to use those strengths builds confidence and competence. It creates satisfaction, fulfillment, and engagement, which lead to creativity and performance (Amabile & Kramer, 2007).

A strengths-based orientation goes one step further to address sustainable engagement by making sure that employees are not only willing, but are also able to go the extra mile to get the job done. It also supports employees’ need for connection. When they have an opportunity to collaborate with people whose strengths complement their own, they contribute to creating the energizing work environment that the Towers Watson study found is key to sustainable engagement.

Help people make progress. We feel good when we accomplish things. Think about how satisfying it is to check something off your to-do list. Conversely, think how frustrating it is to run into roadblocks that impede your ability to make progress. When Amabile (2011b) analyzed the journal entries for workers across seven different companies over the course of a multi-year study, she found that people’s worst days at work were those days marked by setbacks—being stalled, being blocked or feeling like they were moving backward. Too much of this and demotivation turns to disengagement. “The best way to motivate people, day in and day out, is by facilitating progress—even small wins” (Amabile, 2011b, p. 3).

Managers understand that their jobs require delivering tangible results—getting projects to completion on time and on budget, meeting the sales forecast, improving customer satisfaction, etc. As they focus on meeting those big end goals, managers can easily lose track of the daily struggles employees face in trying to make progress against those goals, especially as they face their own daily struggles to get things done.

To make this practice work, managers must learn to step out of the “doing” role to one of directing and facilitating. This is standard leadership development material, but can be one of the more difficult transitions a manager has to make in her career. The problem is that if she doesn’t learn to embrace her role as the director/facilitator, she will not be an effective leader and she will lose the opportunity to help her employees make progress—a key component to work satisfaction and engagement.

A more menacing attack on progress occurs when managers are the source of roadblocks and backsliding through micromanagement, constantly changing strategies, inability to prioritize, perfectionism and inappropriate gating factors, such as taking too long to make decisions, overanalyzing things, involving too many people (or the wrong people) in the decision-making process, and not responding in a timely manner. These issues are rooted in the manager’s own lack of confidence, lack of training, lack of managerial support, and/or the organization’s cultural flaws and weaknesses.

There is obviously a lot to deal with here, but without digressing into a full leadership development thesis on this topic, I will just say that awareness is a good place to begin. If managers can simply start with the realization and daily reminder that they must help people make progress and then consistently take action that supports this, they will do wonders for engaging the hearts of their employees.

Connecting with Souls

Most people spend a significant portion of their life at work or thinking about work. Careers represent an immense opportunity for creative expression and self-actualizing growth. Unfortunately, the workplace often falls woefully short in being a satisfying channel for expressing the soul’s longing to be creative. Yet, this is completely at odds with the need for businesses and organizations to be innovative in order to effectively compete in an increasingly complex and ever-changing marketplace. If humans are innately creative and businesses need creative people to come up with new products and ideas to grow, what is getting in the way of the perfect marriage of capacity and need? In many cases, it is managers.

To be fair, creativity is not the sole domain of managers. However, the relationship an employee has with her manager is a key driver of creativity. The challenge arises in a manager’s awareness and capacity for capitalizing on this responsibility. The traditional business model promotes employees to manager positions or hires recruits primarily based on their ability to perform the functional aspects of the job, not their people skills or their ability to inspire creativity (Eccleston, 2012).

Another threat is that managers unintentionally suppress creativity and hinder progress on meaningful work. “Managers don’t kill creativity on purpose. Yet in the pursuit of productivity, efficiency and control—all worthy business imperatives—they undermine creativity” (Amabile, 1999, p. 1). Being creative is how we evolve and fulfill our potential as human beings and businesses. We have a choice of what to focus our attention on and manifest. Therefore, it is imperative that, as managers and leaders, we embrace the responsibility to stop inadvertently killing creativity and start consciously growing it, in our employees and ourselves.

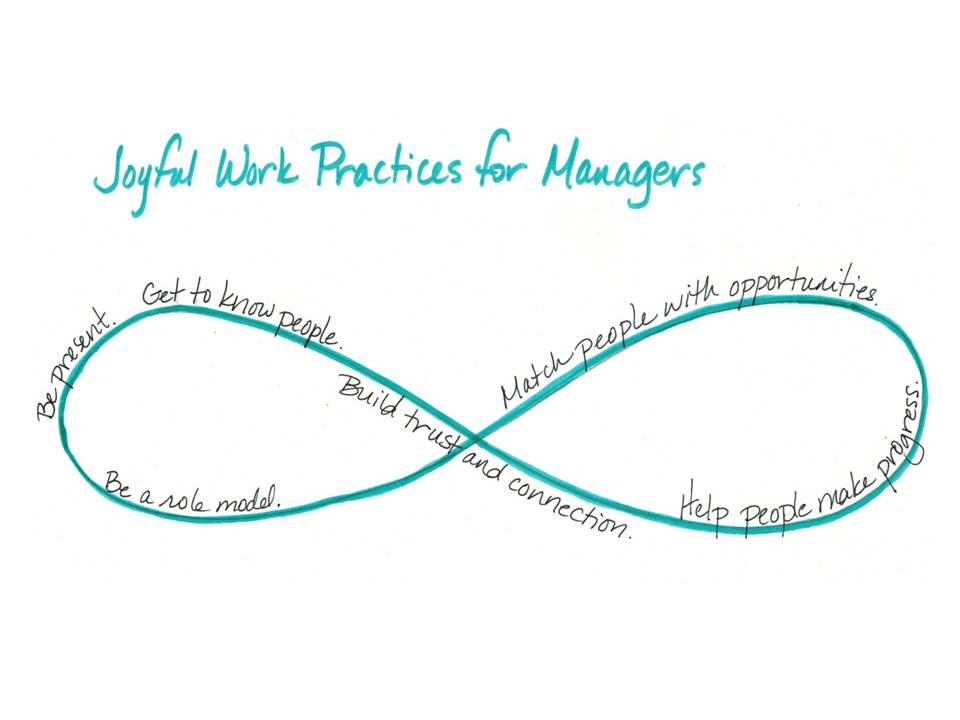

Three Practices for Managers to Connect with Their Employees’ Soul-Born Creativity

Build trust and connection. Trust is an obvious creative factor in that we simply will not expose our raw ideas to people we do not trust. People are reluctant to offer new ideas when they experience having their ideas disregarded, devalued, taken by management without recognition, or used against them (Cangemi & Miller, 2007). Breaches in trust, such as failure to acknowledge innovative efforts, greeting ideas with skepticism, taking too long to respond, and harsh criticism also kill creativity (Amabile, 1999). Three Practices for Managers to Connect with Their Employees’ Soul-Born Creativity

- Build trust and connection

- Match people with opportunities to be creative

- Be a role model

Peter Sheahan, CEO of ChangeLabs, a global behavioral change consultancy, makes the connection between vulnerability, engagement, and innovation:

That deep fear we all have of being wrong, of being belittled and of feeling less than, is what stops us taking the very risks required to move our companies forward. If you want a culture of creativity and innovation… start by developing the ability of managers to cultivate an openness to vulnerability in their teams. (Quoted in Brown, 2012, p. 65)

Managers can inadvertently kill innovation and engagement when they are afraid of showing their own vulnerability by trying to look like they know everything and have all the answers. In their attempt to prove they are in control, managers demonstrate both risk aversion and lack of trust in anyone but themselves. That fear creates disengagement in employees who recognize that new ideas are threatening in such an environment. They learn they are better off keeping their thoughts to themselves and just doing as they are told.

To be innovative means managers not only need to be open to new ideas, they also need to cultivate an environment that makes it safe to be vulnerable enough to speak up. Vulnerability can be uncomfortable, but it is key to sustainable engagement and innovation. It is only through the open connection with each other that people can feel safe to bring their full authentic selves to work. When people trust they can share ideas without being ridiculed or when they can provide feedback in a productive way that does not cut people down, they can tap into a deeper flow of co-creation, where innovation and creativity live. It is imperative that managers model vulnerability, create safe environments where people can feel free to express themselves authentically, and learn how to give and receive feedback in a way that moves people and processes forward.

Match people with opportunities to be creative. Mayfield and Mayfield (2008) captured it in a nutshell: “Unless jobs provide opportunities for creativity, it cannot occur” (p. 981). Managers have the power to align people with opportunities. They can stimulate creativity when they do a good job of matching people with jobs that play to employees’ creative strengths and ignite intrinsic motivation (Amabile, 1999).

To do this, managers build on what they know about employees from engaging the heart—what motivates them, what they are passionate about, and where their strengths lie. They also need to understand the details of each opportunity. “One of the most common ways managers kill creativity is by not trying to obtain the information necessary to make good connections between people and jobs” (Amabile, 1999, p. 10).

The best way to engage inspirees is for leaders to identify and comprehend desires within either the person or the collective … leaders use their knowledge of individuals or groups to create opportunities for them to try new things and support them to believe they can do it. (Searle & Hanrahan, 2011, p. 746)

A source of intrinsic motivation comes from seeing the alignment of an employee’s individual vision with what the organization is trying to achieve. This is also how managers can ignite action: by working to co-create and connect personal visions to the overall vision. When workers can see the intersection between their vision for how they can contribute and the bigger vision, they know how they can take creative actions that will make a difference. They can also feel good about it because there is alignment.

Opportunities should provide creative freedom regarding how to accomplish the goals within an agreed-upon framework. Autonomy to choose how we approach our work allows us to make the most of our expertise and creative-thinking skills (Amabile, 1999).

Building inspiration in an organization is about providing the combination of a guiding framework, which very often is embedded in the corporate or departmental culture, and the freedom to let things happen rather than to control them. (Reckhenrich, Kupp, & Anderson, 2009, p. 71)

Be a role model. The propensity for creativity is demonstrated in leaders who model their own creativity.

Creative leaders promote organizational creativity directly when displaying their own creative behavior and indirectly by promoting a creative climate in the organization by showing appreciation and understanding of creative behavior. (Mathisen, Einarsen, & Mykletun, 2012, p. 378)

Employees may perceive a creative leader as a better partner with whom to discuss ideas to be further developed and improved (Mathisen, Einarsen, & Mykletun, 2012).

If creativity is to add value to the organization, managers first have to understand the principles of creativity as well as develop the mindset, attitude and knowledge of where, when and how creativity will emerge in order to find new solutions. (Reckhenrich, Kupp, & Anderson, 2009, p. 69)

To propagate creativity at work, there must be a propensity for it among both managers and employees. This propensity starts as an openness to learning and a willingness to apply what is learned. Managers not only need to model their own creativity, they also need to spend time learning about creativity, and applying insights and ideas in practice.

Figure 2. Joyful Work Practices for Managers

Growing the Capability for Engaging Hearts and Souls

Managers are not likely to find “Discover and grow the innate creative potential of your employees” in their job description, so how do we create and grow the capability for them to become the Imaginers of Potential and start proactively engaging hearts and souls in our organizations? Although they are key to execution, managers cannot shoulder this shift on their own. Their individual practices with employees must be supported within the larger context of a potentiating culture.

Leader efforts are embedded and limited by the larger organizational system in which they work. They are bounded by an organization’s culture… a culture that chokes creative efforts can be more powerful than a leader’s efforts at growing creativity. (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2008, p. 981)

Creating a Structure to Support Engagement and Creativity

These concepts and practices need to become integrated into the language, expectations and processes for the entire organization by establishing the organizational values, communicating with clarity regarding expectations, and providing a clear method of accountability at the organizational and managerial level. To drive the true integration and successful expression of these values in daily work, companies need to invest in developing both manager and employee competencies. It is important to teach all employees, not just managers, about the values and concepts of the culture, including what is expected of managers and employees in an environment that seeks out and supports the expression of innate creative potential. While formal training to help managers understand how to cultivate engagement and creativity should represent a piece of the overall program, the bulk of the program should be built around integrative learning and development approaches that reinforce the values and concepts, such as mentoring and creating a community of learning and sharing.

Role modeling is a powerful teaching and development tool and speaks volumes about what an organization really believes. Start by conducting an assessment to find the Imaginers in your organization and use them as role models and mentors. Make sure senior level managers are trained, supportive, and modeling the behavior as soon as you begin to communicate about it to avoid credibility issues. Start making promotion and hiring decisions based on criteria that include demonstrated behaviors of Imaginers.

Choosing to Engage Hearts and Souls through Joyful Work

W. E. Deming on a leader’s most important role: “The most valuable ‘currency’

of any organization is the initiative and creativity of its members. Every leader has

the solemn moral responsibility to develop these to the maximum in all his people.

This is the leader’s highest priority.” (Quoted in Sachem, 2010, p. 1)

It seems that in the pursuit of succeeding in business we too easily lose sight of the fact that employees are people with hearts and souls. Under the guise of professionalism, we expect employees to do what it takes to achieve the stated business outcomes. We mold them to our vision of what we think they need to be. We pack more and more work into their daily schedules and expect that they will be good corporate citizens and simply do more with less in the hopes that they will stay employed.

I invite us all to choose a more engaging method to achieve success in business and in the process, unlock the creativity that lives inside our workers. To do this, we need to put joy back into the job. That starts with a very fundamental shift in focus from productivity to creativity.

This might feel like a risky approach to some managers because it may seem “too soft.” They may feel like they will lose control and not achieve the business outcomes. These managers need to be reminded that the payoff for taking the risk to truly embrace a focus on employee potential, engagement, and creativity is happier, more fulfilled employees who care more about what they do, resulting in less turnover, better productivity, and more satisfied customers, which ultimately leads to higher profits and business growth (Kruse, 2012, September). If they take the time to develop employees, nurture their talents, provide them with opportunities to use their innate strengths, help them break through blocks to make progress, and recognize their value, they will not have to worry about achieving their outcomes. It will happen naturally as a result of the satisfaction and motivation sparked in their employees. I think most business leaders would agree that this is most definitely a worthwhile use of a manager’s time and focus.

Figure 3. The core of creative synergy in The Joyful Work Model

When we begin to treat employees as innately creative souls with unique strengths and talents that can be aligned to the bigger vision of what business is trying to achieve, we step into a more expansive space of creative synergy—one that is as good for the business as it is for the individuals working there. It is a model for Joyful Work that creates a positive environment for growth spurred by tapping into the natural pull for self-actualization. We do not have to force productivity and performance; we can engage and inspire it simply by recognizing and nurturing the drive for creative expression that is already within each and every one of us.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1999). How to kill creativity. In Harvard business review on breakthrough thinking (pp. 1-28). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Amabile, T. M. (2011a). The progress principle. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/TEDxAtlanta-Teresa-Amabile-The

Amabile, T. M. (2011b). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. [Kindle DX version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2007). Inner work life: Understanding the subtext of business performance. Harvard Business Review, 85(5), 72-83.

Baumruk, R., & Gorman, B. (2006). Why managers are crucial to increasing engagement. Retrieved from http://www.insala.com/employee-engagement/why-managers-are-crucial-to-increasing-engagement.pdf

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. [Kindle DX version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com. New York, NY: Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Buckingham, M. (2005). What great managers do. Harvard Business Review, 83(3), 70-79.

Buckingham, M. (2008). The truth about you. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Cameron, J. (1992). The artist’s way: A spiritual path to higher creativity. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Cangemi, J., & Miller, R. (2007). Breaking-out-of-the-box in organizations. The Journal of Management Development, 26(5), 401-410.

Castro, F., Gomes, J., & de Sousa, F. C. (2012). Do intelligent leaders make a difference? The effect of a leader’s emotional intelligence on followers’ creativity. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21(2), 171-182.

CIPD. (2012, January). New meaning to ‘squeezed middle’: CIPD research shows middle managers are under most pressure, have worst work-life balance and least sense of job security. [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.cipd.co.uk/pressoffice/press-releases/new-meaning-squeezed-middle.aspx

Eccleston, J. (2012, May). Three in four workers report managers’ lack of leadership and skills. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.personneltoday.com/articles/03/05/2012/58518/three-in-four-workers-report-managers-lack-of-leadership-and-skills.htm

Firman, J. & Gila, A. (2002). Psychosynthesis: A psychology of the spirit. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gallup. (2010). The state of the global workforce: A worldwide study of employee engagement and well-being. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/strategicconsulting/157196/state-global-workplace.aspx

Harmon, W. & Rheingold, H. (1984). Higher creativity: Liberating the unconscious for breakthrough insights. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

IBM. (2010). 2010 IBM global CEO study. Retrieved from http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/ceo/ceostudy2010/multimedia.html

Kruse, K. (2012, June). What is employee engagement? [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2012/06/22/employee-engagement-what-and-why/

Kruse, K. (2012, September). Why employee engagement? (These 28 research studies prove the benefits) [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2012/09/04/why-employee-engagement/

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper.

Mathieson, G. E., Einarsen, S., & Mykletun, R. (2012). Creative leaders promote creative organizations. International Journal of Manpower, 33(4), 367-382.

Mayfield, M., & Mayfield, J. (2008). Leadership techniques for nurturing worker garden variety creativity. The Journal of Management Development, 27(9), 976-986.

McCaslin, M. (2013). Engaging the potentiating arts: Living, learning and leading on purpose.[Unpublished workbook].

Nussbaum, B. (2013, February). 4 ways to amplify your creativity. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.fastcodesign.com/1671773/4-ways-to-amplify-your-creativity

Rath, T. & Conchie, B. (2008). Strengths-based leadership. Great leaders, teams and why people follow. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Reckhenrich, J., Kupp, M., & Anderson, J. (2009). Understanding creativity: the manager as artist. Business Strategy Review, 20(2), 68-73.

Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. London: Constable.

Sachem, J. (2010, March). Inspirational quotes about servant leadership. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://voices.yahoo.com/inspirational-quotes-servant-leadership-5706416.html?cat=7

Schwartz, T. (2012, November). New research: how employee engagement hits the bottom line. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/schwartz/2012/11/creating-sustainable-employee.html

Searle, G. D., & Hanrahan, S. J. (2011). Leading to inspire others: charismatic influence or hard work? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 32(7), 736-754.

Towers Watson. (2012). Global workforce study, engagement at risk: driving strong performance in a volatile global environment. Retrieved from http://towerswatson.com/assets/pdf/2012-Towers-Watson-Global-Workforce-Study.pdf

About the Author

Kirstin McGuire is a catalyst for the fulfillment of human creative potential. She has

over 20 years of experience writing, collaborating with leaders, creating

strategic communications, and facilitating workshops to ignite the potential for

new levels of creativity and engagement in business.

Fascinating article. I like the fact that even by looking at a more soul-focussed perspective much of the recent research on engagement and leadership is supported but with more direct tools to make it happen. A great resource that warrants re-reading.

Excellent, innovative…transformational!!!

Hi Kirstin, is there a tool which you used to measure Joy at work.