Brian and Mary Nattrass

Brian Nattrass

Mary Nattrrass

In the following article Brian and Mary Nattrass (1999, 2002) (who have been organizational change strategists teaching and consulting using The Natural Step framework for sustainability for over 20 years) walk Leaders through a path that shows how to negotiate the resistant Old Story into the life-giving New Story of sustainability in our time. At the Evolutionary Crossroads where they explore, ILR Readers are encouraged to read with open hearts/minds that consider not just the content information about sustainability—but how this way of appreciating the emerging New Story offers a simple and elegant roadmap that enables us to meet people wherever they are on the evolutionary journey to a more sustainable world. Ask yourself what your leadership asks of you in your encounters with others along the way of “Old Story transforming into New Story”. This article will be particularly helpful to anyone who works within an organization (or between organizations) and seeks to be an agent of positive change there.

How ARE We To Go On Together? Our Evolutionary Crossroads

It’s all a question of story. We are in trouble just now because we are in-between stories. The Old Story—the account of how the world came to be and how we fit into it—sustained us for a long time. It shaped our emotional attitudes, provided us with life purpose, energized action, consecrated suffering, integrated knowledge, and guided education. We awoke in the morning and knew where we were. We could answer the questions of our children. But now it is no longer functioning properly, and we have not yet learned the New Story. (Berry, 1985/86, p. 1)

Humanity stands at an evolutionary crossroads—a nexus or meeting point of shifting, conflicting, and contradictory worldviews. A massive and rapidly growing body of evidence informs us that human activities are depleting and destroying life-supporting ecosystems around the world and contributing to changes in the global climate. These dynamics could ultimately jeopardize the viability of our species, homo sapiens, as well as a vast number of other species on the planet. The mounting evidence suggests that if humanity does not change course within a very few years we are in danger of crossing ecological and climate thresholds that could make us an endangered species. If that is the case, we are indeed talking about humanity’s evolutionary prospects.

Our intention in writing this article is that it function as both a useful and an inspirational guide to fellow practitioners—that is, individuals who have both the challenge and the opportunity to work within organizations, particularly large and complex organizations. It is for people who regularly seek to bridge that gap, often feeling more like a chasm, which lies between the reality of day-to-day business life as it is actually lived, and their internal dream of the kind of world that we could have, including the wonder-full (i.e., full of wonder) role that an inspired and co-creative Humanity could play in an our extraordinary Universe—whose fathomless beauty and unimaginable complexity is only now beginning to be understood.

We are literally star-beings. We are stardust come to life. The sub-atomic energy that constitutes the trillions of atoms that comprise the billons of molecules that make up our human bodies came into existence in that unfathomable cataclysm in which our Universe first exploded into existence. How is it that what was once raw energy in quantum dimensions is now able to think and to feel and to love and to aspire to return to the stars from whence it all came? The awe and the magnificence and the essential mystery of our Universe—and indeed, of all life—always surrounds us, every second of every day.

Yet in order to earn our daily bread our eyes are not on the stars but rather on the work right in front of us. Budgets, production schedules, staff assignments, purchasing requests, new product developments, introduction of new technologies—this is the stuff of our daily organizational life. We are judged and rewarded on our performance in fulfilling organizational requirements. Most of the time this feels completely unconnected to our origins in the stars. The vast majority of us who live in the industrialized world have even lost the basic day-to-day awareness of the health of the ecosystems on which our own life depends—an awareness that was once an essential survival skill in our long evolution on this planet. In fact, scientists all around the world are increasingly documenting the warning signs of a planet whose biosphere—our native habitat—is everywhere stressed and in serious danger due to human activity.[i]

We continue to ignore these growing warning signs—or deny their meaning—at our peril. Urgency is thus associated with the task of evolving the dominant worldview, or system of intelligibility[ii], into a New Story that can guide how we are to go on together on this one and only planet we collectively share as home. Daniel Goleman (2009) counsels that we need to develop (and some would say ‘recover’) ecological intelligence:

Today’s threats demand that we hone a new sensibility, the capacity to recognize the hidden web of connections between human activity and nature’s systems and the subtle complexities of these intersections. This awakening to new possibilities must result in a collective eye opening, a shift in our most basic assumptions and perceptions, one that will drive changes in commerce and industry as well as in our individual actions and behaviors (Goleman, 2009, p. 43).

Although this “awakening to new possibilities” has begun, we are still very far from “a collective eye opening”. Making fundamental shifts in our most basic assumptions and perceptions about how the world works and how we should act within it does not happen overnight. Frankly, most of us undergo a high degree of emotional and psychological resistance if our view of the way our world works comes into question or under attack. Lessons from history abound to warn us that the shift involved in moving from one worldview, or system of intelligibility, to another, is unlikely to be smooth or easy.

One such lesson from the not-too-distant past was the reaction and resistance of the Church to the heliocentric model of the universe brought forth by Galileo in the early 1600s, confirming the earlier works of Copernicus, placing the sun at the center of the universe and not the Earth. The worldview of educated Europeans in Galileo’s day was that all heavenly bodies revolved around the Earth. This view had biblical authority behind it, including text stating: “the world is firmly established, it cannot be moved.”[iii] Galileo’s observations showed otherwise. His pioneering scientific work brought down on his head charges of heresy by the Church, he was tried by the Holy Office, and spent the last years of his life under house arrest. This demonstrated again that people do not like it, and generally do not react well—particularly persons in high authority representing powerful interests—when told that their view of reality is false.

Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that our individual and collective experience at the evolutionary nexus point that we are facing now, and will confront in the decades to come, will be bumpy and uncomfortable at best, if not terrifying and catastrophic at worst.

Helping to socially negotiate the new terms, forms, and meanings of the New Story is at the heart of what 21st century leaders in all sectors of society are tasked to carry out. They form the bridge between two realities—equally needing to maintain credibility in terms of the Old Story, yet at the same time inspiring and facilitating the co-creative emergence of the new one. This task is not for the faint of heart or spirit. Until only very recently there were almost no mental models, conceptual tools, or analytical frameworks with which to engage effectively in the physical world with the concept of sustainability. Indeed, as this article is being written, practitioners around the world are writing the manual of sustainability by their daily work in the field.

The vanguard of sustainability leaders, change agents and practitioners arose in the late 1980s and through the 1990s before the term sustainability was part of our social lexicon and before there was even a field of sustainability practice. They helped create the field of sustainability by their actions in identifying the issues and then convincing others to listen to them, and then taking steps to find solutions to the problems identified.

We collectively owe a debt to these sustainability pioneers for their courageous work, because it takes fortitude and a particular skill to operate in the tension and uncertainty that exists in the chasm between worldviews. As a result of their pioneering work, today we can identify and develop the knowledge and skills needed to accelerate and perhaps ease this shift in fundamental understanding of how the world works. This will take leadership in the broadest sense. A leader can be an individual working within a human social organization at any level of that system. A leader can also be an institution or even sector comprised of multiple institutions. Our use of the term “leader” in the rest of this article refers to this broader sense of leadership.

Donella Meadows pointed out that we find the greatest leverage for change in any human system by shifting the paradigm of that system.[iv] Easy to say, hard to do—especially when we are talking about an evolutionary shift for humanity as a whole. Nonetheless, this is our evolutionary challenge. How do we go about achieving this task? What can individuals and organizations do now and in the near future to take on and succeed in such a massive project? Is there a roadmap we can use to orient us in this process, one that will help us understand, develop, and employ the leadership skills required to meet this evolutionary challenge?

In the following sections we explore these questions and offer a simple schematic to help us see the monumental task in which we are all collectively engaged. In particular, we investigate the role that leaders play in socially negotiating the new terms, forms, and meanings that are needed for the New Story to emerge and become our new system of intelligibility. The only way that we can learn this New Story is by collectively creating it.

-

How we move from one worldview, or system of intelligibility, to another

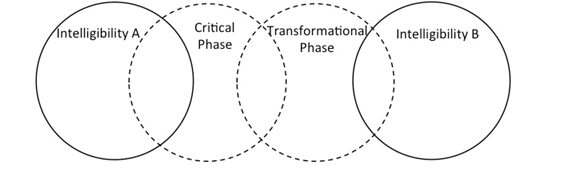

“We are in trouble right now,” Berry tells us, “because we are in between stories”. We are operating in the space between the Old Story that is not functioning properly and the New Story that is still unclear and uncertain. This is a place awash with tension made greater by the fact that we lack well-defined maps for traversing this territory. Although it is too early in the game to provide an explicit roadmap to the New Story, we offer a simple schematic (Figure 1) to help orient us in this grand adventure of what it takes to move from one system of intelligibility to another. By gaining a better picture to orient us, perhaps we can also see how to accelerate and ease the process.

Figure 1: The Phases of Moving from One System of Intelligibility to Another (based on Gergen, 1994).

The process of moving from one system of intelligibility (Intelligibility A) to another (Intelligibility B) is not instantaneous. It occurs through phases. At the outset we have Intelligibility A, a coherent, self-contained array of propositions about how the world is and works. This system of interrelated beliefs, values, constructs, and stories renders our world intelligible. It provides the filters and the boundaries that enable us to coordinate actions together in the world. Without our being aware of it, our system of intelligibility influences and constrains our choices regarding what is relevant for us to observe, know, examine, and question about reality, and how to structure, interpret, and validate our inquiries to advance our knowledge, understanding, and action. We tend to overlook, ignore, downplay or attempt to disqualify evidence that calls the system or some of its core propositions into question. By definition, what is outside of our system of intelligibility is not real to us. As long as our system of intelligibility remains coherent and intact, we can make sense of the world and our place, experience, and actions within it, individually and collectively.

A Critical Phase arises when something in our experience exposes fault lines in the bedrock of our reality. At first when anomalies appear, our impulse is to explain them away as errors in observation, understanding or measurement or to simply ignore them and assume they will go away. We still trust in the coherence of our system of intelligibility and believe that any anomalies we experience are insignificant, erroneous or explainable and solvable within the constructs of that existing worldview.

As anomalies remain unresolved and grow in substance, frequency, number and/or perceived consequence, alternative explanations arise that use terms and metaphors from outside the boundaries of Intelligibility A. As more voices join the discourse, give name to the anomalies, point out their implications, and criticize the current paradigm, a sense of crisis arises as the fault lines in Intelligibility A become more obvious, irrefutable and even dangerous. Tension grows among the differing systems of intelligibility. Potentially, maybe inevitably, this crisis results in battle lines being drawn intellectually, philosophically, politically, ideologically, and emotionally.

We can observe this happening today in North America and around the world on the issue of climate change. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence documenting the fact of global climate change, many of today’s vested interests, particularly those whose profitability depends on the continued exploration for, extraction, refining, distribution, and consumption of hydrocarbons, such as oil, natural gas, and coal, vehemently deny the existence of climate change, or as a fallback position, deny that it is human activity that causes climate change if it exists at all. Collectively, these hydrocarbon-related interests undoubtedly represent the most powerful vested commercial interests in the world today.

When fault lines appear in the system of intelligibility that structures our world, we are understandably shaken. Suddenly, we learn that Earth is not actually the center of the universe, or that the Emperor/King/Pharaoh is not actually divine. The firm surface that we stand on shakes like a shift in tectonic plates. We suddenly find ourselves in the uncertain and confusing terrain of earthquake territory. We are no longer certain about the solidity of the ground on which we stand. As anomalies grow in number, strength, and credibility, we begin to lose confidence in the complex web of stories and tacit assumptions that make up our worldview, yet we do not have a coherent web to replace it. Our reaction during this phase may be akin to the stages we experience as a result of loss and grieving, for indeed we are losing a sense of surety as we investigate the implications of these fault lines. We may go into denial, become angry, bargain with ourselves, and others, as we seek compromises that lessen our need to change, and go into despair or depression as we struggle to accept what our discoveries mean. “Oh Lord, if I can just have that new Porsche, I’ll make it a hybrid!”

The Critical Phase gives way to the Transformational Phase as the implications of the fault lines are more fully elaborated and as new ideas, previously discarded ideas, new approaches, and new solutions emerge. “As the implicational network is progressively articulated, an alternative system of intelligibility emerges (B). As this system is increasingly employed in the ‘ontology’ of the world (for example, in naming and interpreting what there is), its credibility gradually rivals that of Intelligibility A: it approaches the status of plain talk or common sense” (Gergen, 1994, pp. 12-13). A new paradigm or New Story takes form, gains followers, and evolves into a coherent, self-contained array of propositions about how the world is and works. For example, as the initial stages of the Scientific Revolution unfolded, when it finally became accepted that we could no longer claim scientifically that Earth was the center of the universe, or even the center of the solar system for that matter, we could still take comfort that Man was the dominant species on this planet and that dominion over Nature was our destiny. Scientific advances in our understanding of how the world works, particularly work demonstrating the interdependence and co-evolution of all life on Earth, have undermined even the comfort of that outmoded position.

-

The Sustainability Discourse: how we are developing and resolving conflict among systems of intelligibility

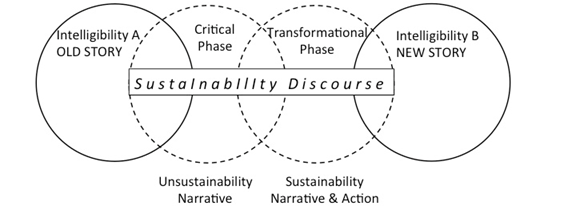

Using this schematic (Figure 2), we can see how the sustainability discourse that has emerged over the past half century is our collective attempt to move from the Old Story that is no longer functioning to a New Story that does.

Figure 2: Bridging the gap between stories and resolving the conflicts among systems of intelligibilities through the sustainability discourse.

The sustainability discourse unfolds across the two phases that form the uncomfortable gap between the two stories. In the Critical Phase we articulate anomalies, essentially using conventions of negation that undermine confidence in the coherence of the dominant form of intelligibility. To communicate the implications of these anomalies we introduce new meaning using terms and forms that make the critique credible. We use narrative accounts, such as stories and descriptions, to communicate the incongruities we observe and the implications of those incongruities. We call this phase of the sustainability discourse the unsustainability narrative, as the fault lines it articulates suggest that the Earth on which we depend for life may not be able to sustain humanity over the long-term if current trends of human activity continue. The unsustainability narrative is fundamentally about our evolving understanding of the relationship between humans and the rest of nature.

2.1. Exploring the unsustainability narrative

Over the course of the last half century countless narrative accounts have pointed out the incongruities in the Old Story. Some of these accounts have focused on symptoms—the outward indications that our story is no longer functioning. Other accounts have sought out fundamental causes—the set of assumptions we hold that drive and reinforce the symptoms we observe. Here we will highlight some underlying assumptions from the Old Story together with alternate explanations that have emerged.

- Assumption: Nature, the living planet, always has and always will provide the life-supporting resources humanity needs to survive and thrive (e.g., air to breathe, clean water to drink, topsoil for food, and materials for shelter and clothes). This assumption about reality has remained true for all of our species’ existence, until now.

Alternate explanation: The Earth was not always an environment hospitable to life, as we know it, especially for human life. In fact for most of its existence, the Earth would have been considered a deadly, hostile environment to us. It is all a question of having environmental boundaries within which life can exist. Homo sapiens is a very new species on this planet with its approximately 4.5 billion-year history, and we exist within what is actually a relatively narrow band of environmental parameters. Although our species is resilient and adaptable within those parameters, there are real limits to the environmental conditions in which our adaptability can ensure our survival. In addition, although the Earth is still rich in resources, many of those resources, such as oil and natural gas, are finite. As humanity’s demands for life-supporting resources grow, we place greater and greater pressure on the Earth’s systems, which, at some point, will not be able to regenerate sufficiently to continue to support us. There are physical limits to population and industrial growth as we live and conduct business in a resource-constrained world.

- Assumption: Nature, the living planet, can absorb and transform all of the waste that humanity produces despite the seemingly insatiable demand of a rapidly growing and increasingly urban, industrialized, and consumerist global population. This assumption about reality has remained true for all of our species’ existence, until now.

Alternate explanation: The Earth cannot metabolize all the waste humanity produces in a way that renders that waste harmless or beneficial to human life and to the existence of other species. As un-compostable and potentially toxic human-made waste builds up in Nature (i.e., in our air, water, and land) it threatens the health and viability of communities and ecosystems.

- Assumption: Nature is big and powerful, humanity is relatively small and at the mercy of Nature’s powerful forces. While human actions may inflict local or regional harm to natural systems, we lack the capacity to irreparably destroy major ecosystems, or significantly alter major global systems, such as the climate. Humanity certainly does not have the wherewithal to alter or upset the ecological balance of big Earth systems or undermine the very life supporting systems on which humanity depends. No matter what destruction or depletion takes place in Nature even by our hands, we will develop the knowledge, technology and means to adapt and survive. If we do destroy local habitats, we can always move somewhere else on this big planet. This assumption about reality has remained true for all of our species’ existence, until now.

Alternate explanation: we are living in a new epoch increasingly being referred to as the ‘Anthropocene’ denoting that humans (‘anthro’) now have a decisive influence on the state, dynamics, and future of the Earth system. Humanity has become a geologic force that can alter, deplete, and even destroy the life-supporting systems on which we depend. According to the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy’s working group on the Anthropocene, this name indicates that “many geologically significant conditions and processes are profoundly altered by human activities” including, but not limited to:

- Erosion and sediment transport associated with a variety of anthropogenic processes

- The chemical composition of the atmosphere, oceans and soils, with significant anthropogenic perturbations of the cycles of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and various metals

- Environmental conditions generated by these perturbations; these include global warming, ocean acidification, and spreading oceanic ‘dead zones

- The biosphere both on land and in the sea, as a result of habitat loss, predation, species invasions and the physical and chemical changes noted above[v]

The assumptions just listed have been part of our species reality for as long as our species has existed. Another, more recent belief that is revealed in our unsustainability narrative, can be expressed as follows:

- Assumption: humans are superior to, and separate from, nature.

This is a relatively recently constructed belief compared to the age of our species. We can trace the roots of this belief back in Western civilization and see how it is integrally connected to the rise of modern civilization and our prevailing system of intelligibility. C.S. Lewis suggests that a small number of Greek thinkers effectively invented nature. Or rather, invented “Nature” with a capital N based on the idea that the great variety of phenomena that surrounds us could be gathered under a single name and talked about as a single object.[vi] Evernden (1992) comments that this very possibility of a thing called nature is as significant a development as a fish having a “thing” called water. Where once an invisible, preconscious medium existed through which each moved, there now exists an object to examine, describe, and know. (pp. 19-20).

By the 17th century, the term nature referred increasingly to a physical non-human world that could not only be known, it could also be conquered and controlled for the benefit of humans. As the Age of Enlightenment dawned around the beginning of the 18th century, so did modernist beliefs about the self-including the idea that each individual is able to observe the world for what it is and decide rationally on one’s best actions.

[T]he perfect companion to the fully functioning mind is an objectively knowable and rationally decipherable world. It is in this respect that the work of Enlightenment figures such as Isaac Newton and Francis Bacon were of pivotal importance. Their writings convincingly demonstrated that if we view the cosmos as material in nature, as composed of causally related entities, and available to observation by individual minds, then enormous strides can be made in our capacities for prediction and control (pp. 805).[vii]

Nature could be known and deciphered as something mechanical, like a set of clockwork parts. Instead of essence, the water in which we swim, nature becomes a treasure house of commodities to be extracted and used for human benefit. The human-nature dualism separated the properties of the world into two domains: nature and humanity; and it placed humans, as the beings capable of reason, in charge of that process with “license to adjudicate the contents and behavior of nature” (Evernden, 1992, p. 89). From this perspective, humanity is unique, unlike anything else on Earth. Everything else is relegated to nature.

By the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th Century, “nature” is not only separate from and knowable by humanity, it is understood as property: the source or warehouse of valuable resources and the infinite sink for our wastes. From this standpoint, nature belongs to humans and exists for our use. This view of nature is prevalent today and integral to how we operate in the Old Story. Whether validated by Descartes, or contemporary resource-driven political and economic actors, nature is seen as a storehouse of commodities to be exploited solely for the benefit of humans, usually a privileged subset of humans who hold the deed/rights to those resources and have the capital and technology to extract and use them. Whether humans harvest, manage, protect or conserve it, nature is “not human” and it is commoditized and owned.

Alternate explanation: The term “nature” does not refer to an external objective reality that is simply mirrored in the use of the word. The meaning of the term “nature” is negotiated and affirmed through our relationship with others in a given community or communities. These relationships are what make possible an intelligible world of objects and persons as we continuously generate meaning together (Gergen, 1999, p. 48). The shared language of the community is the means by which objects, persons, and events become real (Gergen and Gergen, 2003, p. 4). Gergen (1999) remarks:

Relations among people are ultimately inseparable from the relations of people to what we call their natural environment. Our communication cannot exist without all that sustains us – oxygen, plant life, the sun, and so on. In a broad sense, we are not independent of our surrounds; our surrounds inhabit us and vice versa. Nor can we determine, as human beings, the nature of these surrounds and our relation with them beyond the languages we develop together. In effect, all understandings of relationship are themselves limited by culture and history. In the end we are left with a profound sense of relatedness–of all with all–that we cannot adequately comprehend (p. 48).

The human species—albeit the dominant species on the planet, with a distinctively well-developed cerebral cortex that gives us some adaptive advantages—is still totally dependent upon the rest of nature to survive. Even with all our clever technology, we cannot separate ourselves from the life-supporting systems that sustain us and with which we evolved.

Humanity evolved within the natural world. We share part of the genetic codings of all living species, especially other mammals. We are part of the food chain; we eat and are eaten; our bodies are the hosts of bacteria, yeasts, parasites; when we die, our bodies form the parts of other living creatures. We are, as are all living things, dependent upon the natural cycles of water, nitrogen, carbon dioxide. If the rains fail, as they frequently do, we starve…Humans have evolved with unique characteristics, as have all species, and this difference has enabled them to move to a position of control. But if, for instance, there was abrupt climate change, humanity could easily become extinct, while other species, better equipped for such an event, could gain ascendancy (Berry, R. J. ed., 2006, pp. 70-71).

However we imagine our relationship with the rest of nature, if we do not have air to breathe and water to drink we no longer exist: game over. The future of our species depends upon the balance woven by the “hidden web of connections” within nature and the relationship between human activities and natural systems. Some relationships are non-negotiable. We depend upon the Earth’s maintaining the chemical and physical balances required to sustain our form of life, balances that did not always exist on this planet. In the early history of Earth, for example, the atmosphere was a toxic blend of compounds such as methane, ammonia, nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide and water vapor, a place inhospitable to human life. It took more than two billion years of plant life extracting energy from sunlight through photosynthesis, using up carbon dioxide, and giving off oxygen, to create a place congenial for the life forms we know today.[viii] These life forms exist within a relatively small range of chemical and physical relationships. Today, for example, oxygen makes up about 21% of the Earth’s atmosphere compared to .2% about 2 billion years ago. It is estimated that the lower limit of oxygen concentration to support life is approximately 18%. Although the Earth can exist within a wider range of variation, human life cannot.

Over eons of time, plant life or the animals that consumed it, decayed and their carbon became preserved and sequestered beneath the Earth’s crust through pressure, bacterial processes, and heat. Over millions of years these organisms changed chemically into what we now call fossil fuels. Now, as we burn these fossil fuels, we release these ancient carbons into the atmosphere where they combine with oxygen to create carbon dioxide (CO2). As we do so, we actually change the chemical composition of the atmosphere. The more fossil fuels we burn, the more carbon dioxide we create, and the higher the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere. Although carbon dioxide makes up a relatively small proportion of gases in the Earth’s atmosphere (around 1%), it plays a vital role in keeping the Earth warm enough for life. The rise and fall of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere is linked to the rise and fall of the Earth’s global temperature: as CO2 concentration goes down, temperature goes down; as CO2 goes up, the temperature goes up.

Carbon dioxide, estimated to be as much as 10% of the atmosphere in the earliest part of the planet’s history, was removed from the atmosphere over eons. Now, humanity is increasing the CO2 in the atmosphere in a matter of centuries. At the beginning of the industrial revolution, it is estimated that there were approximately 280 parts of CO2 per million parts of other atmospheric gases. Today the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates we are at 397 parts per million and CO2 concentrations continue to rise at an unprecedented rate of 1.5-2.5 parts each year. In evolutionary terms this is a meteoric shift that, if continued unabated, could tax the adaptation prospects of many species including our own.

The scientific debate is over regarding the relationship between human activities and global warming.[ix] The debate continues about the relationship between the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and significant thresholds past which weather becomes extremely erratic: where we lose the polar icecaps and glaciers around the world, the sea becomes dangerously acidified, and adaptation for all species on the planet becomes more challenging. Levels in the range of 450 and 550 parts per million are being used in international climate talks to indicate the limit humanity should set. These are levels the Earth is expected to reach by the mid-21st Century if dramatic action is not taken, and some believe even if dramatic action is taken. Recently leading scientists[x] warn that we are already past the safe upper limit of atmospheric CO2, which they now estimate to be 350 parts per million. Out of this vortex of relationships, the future of humanity and many other species with whom we share this planet is being forged.

Some relationships are negotiable, for example the relationship between the growth of both population and material consumption, which place rapidly escalating demands on the Earth’s resources and systems, and the Earth’s continued ability to regenerate clean air and clean water, and provide new resources such as food and timber, and deal with our wastes. More people on Earth means that we need to produce more food, more shelter, more clothing, more clean water, etc. to meet even our most basic needs. In our current growth-oriented, take-make-waste way of life in industrial consumer culture, as the world continues to industrialize and affluence rises, humanity demands more and more goods and services beyond basic human needs: we simply consume more stuff. The more we consume, the more waste we produce. The more waste we produce, the more we pollute our air, water, land, and ultimately our own bodies. The more synthetic persistent compounds we use to meet the growing demands of consumer culture, the more substances we emit into natural systems with deleterious effects. When these are substances that nature does not recognize and break down as food, they eventually build up in the food chain, some to levels that are toxic to humans and other species.

We have only one planet. The urban and industrialized way of life that prevails on it has a massive “ecological footprint,”[xi] a new term created to help us understand the relationship balance between humans and the rest of nature. An ecological footprint is a way to describe the amount of biologically productive land and sea area needed to regenerate the resources a human population consumes, and to absorb and render harmless the corresponding waste that it produces. Estimates are that:

The ‘ecological footprint’ on the earth has become so large that were everyone to achieve the U.S. standard of living, to which many aspire, using current technologies, human beings would need five more planets to sustain them today! If world population increases to 10 billion by the year 2030 or so—only one generation—as is currently predicted, the amount of biologically productive space will fall to 1 hectare per capita, and less than that if humans continue to degrade land and sea space. Reaching the current U.S. standard of living for everyone will then require an additional nine planets.[xii]

The relationship between how we as a species choose to live on the Earth and the Earth’s ability to continue to sustain our species is not altogether fixed. Where the relationship is negotiable, the terms need to be negotiated within our human systems. Although we cannot change the chemical and physical limits within which human life is possible, or magically push the Earth’s ecosystems beyond their capacity to meet our constantly growing needs, we can and must socially negotiate a system of intelligibility that does not render our existence on this planet unsustainable. Frankly, the Earth has existed and will continue to exist without us. The unsustainability narrative is not about “Saving the Earth,” it is about “Saving Humanity.

We can trace the modern roots of the unsustainability narrative back more than 50 years to the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring (1962), one of the most influential early books raising environmental awareness in American culture. Silent Spring called attention to the threat posed to humans by the continued spraying of DDT, a synthetic chemical compound used to kill disease-carrying insects. The conversation about the potentially damaging and unintended environmental and human health impacts of human activities, especially one initiated for the most noble of reasons, had begun in its modern form. Silent Spring became a voice for growing environmental awareness and environmentally related questions.

The publication of the book helped galvanize the modern environmental movement into a force for political action.[xiii] During the ensuing decades the unsustainability narrative grew in scope, depth, and force. For decades we still did not have a term to pull the story together, but through our narrative accounts we began to connect the dots of data: ice caps melting, oceans warming, sea levels rising, reefs at risk, water scarcity, climate change, rising population, growing income disparities, displaced communities, environmental refugees, new vectors of disease, collapsing fish stocks, deforestation, and ecosystems collapsing. Today, these diverse elements have been woven together into one story that summarizes the rift in our reality: current human society is not sustainable, the future of humanity is at serious risk, and humanity is the cause of its own problems.

As the unsustainability narrative grew, new terms and ideas were explored (e.g., the concept of ecological footprint previously mentioned) to make sense of the fault lines. Sense making is an inherently communal activity. We make sense of our world through the stories, concepts and ideas that we share with one another. In so doing, we make meaning together. These narrative accounts become intelligible because we have a shared language with shared understanding that make them meaningful. Creating a shared and meaningful language is thus mainly a function of social interdependence: we socially negotiate the meaning of the terms and forms we use. For example, the term sustainability has become invested with new significance over the past 2-3 decades through a process of conveying and agreeing upon what we mean when we use the term with one another. [xiv]

We not only live in a world of nature, we live in a world of words. Long-term usage within a community is what invests words with their meanings (Gergen, 1999). This means that in our search for new terms and forms of expression, we must of necessity rely upon the use of metaphor—words or terms taken out of one context of usage and used within another context. To create new meaning, we need to begin with our already jointly constructed language and our common understandings. “The difference between literal and metaphoric words then is essentially the difference between the conventional and the novel. In this sense, all our understandings can be seen as metaphoric if we but trace them to their origins…the common words by which we understand our worlds are typically appropriated from other contexts” (Gergen, 1999, p. 65).

The social negotiation of new terms and forms is thus a process of associating new meaning with conventionally used language. We appropriate terms from other contexts and invest them with new meaning. We do this through sense-making conversations that lead us to new questions that use terms in new ways. Is humanity bankrupting nature? Is humanity on a collision course with the natural world? What is our ecological footprint? What are ecosystem services and how do we calculate their value? Are human activities causing climate change? What are the limits to growth on this planet? Is there a population bomb ticking? Can we meet our needs today and leave enough for future generations to meet theirs as well? What does it mean to overshoot ecological capacity?

A good example of this process of associating new meaning with conventionally used language within a shared social context comes from our work with Nike, the world’s largest and most well-known manufacturer of athletic footwear, clothing, and equipment. Nike has a sports and business culture that is highly competitive—both internally and externally. In 1999, idealistic and very well-meaning people began a sustainability initiative within Nike. They chose a spiritually based metaphor from Tibetan Buddhism and called their initial sustainability initiative Project Shambhala. This small, pioneering group loved this name and very much identified with its spiritual foundations. Unfortunately, senior management perceived this as a cult starting within Nike’s midst and acted rapidly to crush it within the first year. This idealistic group made a fundamental mistake: they did not employ metaphors that made sense within Nike’s own culture—business, sport, and innovation. Subsequently, new leaders for Nike’s internal sustainability initiative emerged and made sure that the initiative was tied to innovation, a core value and competency of the company. By strategically demonstrating that sustainability provided a new lens with which to view products and materials, and that this new perspective could add value to the company by helping to drive innovation throughout the supply chain, sustainability received a new hearing and an increasingly enthusiastic reception by senior management. With much work over time by many committed internal activists, sustainability became known as a driver of innovation and good for business. Today, some 15 years later, Nike is a world leader in corporate sustainability and for years the sustainability department has been called Sustainable Business and Innovation (SB&I)—a long way from the lovely but absolutely inappropriate metaphor for Nike of Shambhala.

2.2. The leader’s role in the Critical Phase

The Critical Phase is uncomfortable. As the implications of the unsustainability narrative become more evident, the challenges revealed in this phase can become overwhelming, even debilitating. The leader’s role is to:

- Courageously enter and stand in this earthquake territory no matter how disorienting;

- Conscientiously and boldly examine the fault lines that are emerging even if they call into question one’s own fundamental assumptions and beliefs;

- Create and facilitate sense-making conversations with others to discern which elements of the unsustainability narrative are relevant and what they mean to the human system in which the leader acts;

- Co-create the terms and forms that will help others understand the meaning and relevance of the unsustainability narrative and communicate those through compelling narrative accounts; and

- Facilitate the movement from the Critical Phase to the Transformational Phase by:

- Helping others to navigate the inherent tension associated with the Critical Phase, recognizing and working compassionately with the psychological and emotional resistances to change that may arise; and

- Evolving the unsustainability narrative into one that socially constructs meaning around what it means to be

-

How we are co-creating sustainability through narrative and action

In the Transformational Phase, our discourse shifts from a critique of the Old Story and making the warning signs about our unsustainability intelligible to investigating what it actually means to be sustainable. In the beginning we use the term sustainable not because we have already socially negotiated what the term means, but because our impulse is to metaphorically negate the negation: we do not want to be unsustainable, thus we must want to be sustainable. Although the implications of what it means to be unsustainable are becoming more evident, the implications of what it means to be sustainable are still unclear.

We are certainly some distance away from a fully formed Intelligibility B that approaches the status of common sense or the plain-language of a shared worldview. This means that as we enter the Transformational Phase tension not only still exists, it is likely to increase. We no longer have confidence in Intelligibility A and Intelligibility B is not yet fully formed. We exist in what Joseph Chilton Pearce (1973) in his book, The Crack in the Cosmic Egg, aptly calls a half-baked metanoia, a shift that is incomplete and thus uncertain and ambiguous. Our real work is just beginning.

Negating the Old Story is not the same as generating a New Story. The Critical Phase can only carry us so far. The second phase of the sustainability discourse moves away from forms of negation to the work of creating and validating new terms, forms, and propositions that provide greater coherence to our system of intelligibility. We begin the hard work of resolving the tension among worldviews while still needing to operate effectively in a world structured around the story that is unraveling. We need new ideas, new approaches, and new solutions. We may need to reclaim previously discarded ideas, approaches, and solutions. And we need to do this without causing severe disruptions and pain.

We ask new questions using new terms: What constitutes sustainable development? What fundamental system conditions need to be met for global society to be sustainable? How do we run our business in better balance with nature? How do we create shared value that advances environmental, social, and financial wellbeing? How do we create and measure a triple bottom line? What is a purpose-driven organization? How do we engage in Responsible Sourcing? How do we make sustainable products? How do we conduct lifecycle analysis? What does it mean to design products cradle-to-cradle? What is our social and environmental responsibility? How do we become a restorative company? What does it mean to be a life-sustaining civilization?

To move out of the Critical Phase requires more than compelling narrative accounts, albeit these continue as important vehicles for creating shared meaning. We begin to recognize that what sustainability means can only be defined together through our social and communal interactions, because creating new meaning is a function of our social interdependence. We socially construct meaning around the new term sustainability through the ways in which we differently define, coordinate, and carry out our activities in our human systems, especially our most powerful social and organizational institutions. These human systems are the crucible in which the new system of intelligibility must gain relevance, meaning, and ascendancy for the new intelligibility to take form at the scale that is needed.

Even before we have fully defined sustainability and fully constructed Intelligibility B, we need to act as if we know what it means because it is our coordinated action that generates and substantiates meaning. In other words, we need to enact sustainability as a way of rendering the term meaningful. We can then use narrative accounts to share and validate the new meaning enabling others to coordinate their activities differently, thus growing and perpetuating the social conversation about sustainability and the social construction and validation of meaning around the term.

Using the Nike example given earlier, in 2000 if you had asked most people in Nike, “what is ‘sustainability’?” you would have received a very broad assortment of answers from “no idea” to “some kind of a weird Buddhist cult.” In the ensuing years, a wide range of people including product designers, material specifiers, sourcing agents, and distribution center managers all jumped into the conversation, making meaning with each other in the process. In those earliest years of the sustainability conversation, for a product designer “sustainability” could have meant reducing the amount of waste generated in manufacturing; while for a distribution center manager, “sustainability” could have meant reducing the amount of electricity and water used at the facility. It meant many different things to different people in different places across the global organization. However, collectively a meaning began to emerge over a period of years that had significance to people within Nike and ultimately became a powerful organizing principle within the company. The key thing to understand is that the meaning of “sustainability” emerged as a social construction among co-workers over time. It was not defined or mandated by an authority figure. Today, in 2015, Nike produces one of the most well-respected sustainability reports of any organization of any kind in the world, it has made major commitments to integrating sustainability practices across the company globally, and we believe that most people in the company today would be able to provide some form of description of “sustainability” that would relate positively to the company’s business and its impact in the world.

Because the interplay of our narrative accounts and our actions is vital for socially constructing meaning, we call this transformational phase sustainability narrative and action. We still need to create compelling narrative accounts that explore what sustainability is rather than what un-sustainability is not. And we need to coordinate our actions in alignment with our ideas of what sustainability is in order to make those narrative accounts meaningful. We expand and deepen the sustainability discourse through narrative accounts that invite others to explore this territory with us. It is not enough to talk about what is or is not more sustainable, we need to imagine and coordinate actions that express, reinforce, and confirm what the new terms and forms mean—as took place within Nike. We “create” sustainability together by “doing” sustainability together.

Now we come to the really tricky part. We need to do and achieve this within corporations, government agencies, educational institutions—that is, every kind of organization—operating primarily as if the propositions of the Old Story are still valid!

Virtually any organization of any substance has its worldview, its system of intelligibility, rooted firmly in the Old Story. Each operates, and succeeds or fails, within the underlying assumptions found in the Old Story. In turn, individual organizations must still operate within a global system that is also massively embedded in the Old Story. And in order for any organization to be an influential leader of change for sustainability, it must continue to be successful within the existing Old Story system. Public companies, for example, must continue to show growth and profits, and report them to shareholders every three months, all the while trying to revision and recreate the company and its markets from a sustainability perspective. The task we face is like nothing that has ever taken place in industrial society—it is comparable to rebuilding a jet liner while in flight 10,000 meters above ground. How do leaders help lead this transformation from inside the very systems that need to change, while at the same time avoiding major economic or social disruptions?

The late futurist, Willis Harman, said that the best analogy he had ever heard as to how this can be accomplished is that of a larva becoming an insect. “As the caterpillar approaches the time of metamorphosis, certain cells within the caterpillar’s body begin to develop – biologists call these imaginal cells. These cells begin the process of building the various parts of the new organisms of the butterfly. The new parts expand and emerge, and the tissue in between disintegrates, and in a very smooth and non-disruptive way, the caterpillar becomes a butterfly”.[xv]

Leaders must become the imaginal cells of the new system of intelligibility. Long before sustainability becomes “common sense,” actions consistent with it can begin to make “local sense.” The practical relevance of these local successes demonstrates and reinforces how the new system makes sense. Organizations, for example, can create sustainability pilot projects to test the feasibility of an innovation on a small scale with low risk to the organization before committing to roll it out on a large scale. These “local sense” actions can be seen as one way in which leadership imaginal cells begin to build the various parts of the new way of conducting business. Successfully coordinated action in alignment with the new worldview engenders expanded possibilities of acceptance and expanded commitment to that worldview as these successes expand and emerge. Coordinating action becomes a significant means for shifting paradigms. In turn, the shifting paradigm becomes stronger as a guide for coordinating action. These dynamics arise together. Meaning emerges from what we say and what we do.

We certainly have ample evidence that this dynamic is well underway. When we began consulting on sustainability two decades ago—that is, inventing the practice with our clients as we went along—using the word “sustainability” often evoked what one colleague called the “stunned mullet look,” Australian slang for being bewildered or uncomprehending. The term sustainability was unintelligible in most contexts; it was certainly not meaningful to most businesses. In just over two decades, the term “sustainability” has not only gained meaning, its use in diverse contexts is expanding rapidly. References to “sustainability” now show up almost everywhere—from esoteric academic treatises, to political speeches, to commercial advertisements, and to all manner of popular culture media. Today we have sustainability indicators, sustainability reports, sustainability strategies, sustainability consultants, sustainability education programs, sustainability conferences, seminars, trainings, and sustainability practitioners. Sustainability has gone from the margin to the mainstream of social discourse. At the same time, we often hear that there still does not yet exist a clear or good definition of sustainability.

In fact, what we eventually call the New Story may not use the term sustainability at all. As architect and author Bill McDonough once joked, if we asked you, “What’s the state of your relationship with your spouse or significant other?” and you replied “sustainable”, how excited would we be for you? Does that word elicit images of romance, sensuality or intimacy in a couple’s context? We think not. At this stage, we don’t know what term will capture the essence of the New Story. What we can do, however, is articulate some new propositions that are part of the sustainability narrative that can help get us there. And we can explore some of the implications of those propositions so that we can enact them with each other through our day-to-day activities.

- Proposition: We are all part of interconnected and interrelated systems within systems. Our actions and choices in one part of this web of systems can beneficially or harmfully impact other parts of the web of systems.

Implication: as an organization we need to see and understand the systems in which we are embedded and the systems embedded in us; and we need to view our choices and actions from this systemic perspective. These systems include both environmental and social systems.

- Proposition: We live in a resource-constrained world.

Implication: as an organization we need to take responsibility for the way we use all of our resources and operate with the greatest possible resource efficiency: doing more with less. We need to know what resources we use or cause to be used—such as electricity, water, and the materials used in both products and buildings—understand how they are used, and coordinate our actions such that we use them most effectively. We need to exercise wisdom and learn how to live in conscious balance with the rest of Earth’s natural and social systems so that we can safeguard the planet’s resources for our use today while at the same time ensuring sufficient will be available for the use of future generations.

- Proposition: There is no “away”. The waste we produce, toxic and non-toxic, visible and invisible, enters into and impacts environmental and social systems. Because we live in one global system, waste generated on one side of the planet can often be found in other parts of the planet far removed from where it is generated. We are responsible for the waste we produce or cause to be produced through our activities, we need to coordinate our activities to eliminate toxic waste, and we need to reduce as much as possible other forms of physical waste.

Implication: as an organization we need to understand and take responsibility for the material and energy flows generated by our activities, identify where we generate waste or cause it to be generated, and eliminate the very concept of waste from our activities. We need to eliminate the use of toxic materials, ensure that all materials related to our activities are used to optimum efficiency and effectiveness, and ensure that all materials are either compostable and can be metabolized by nature or can be metabolized through our human-made technical systems to become feed-stock for other products or processes.

- Proposition: Humanity is a global force of nature, capable of altering and even causing irreparable harm to the Earth’s complex natural systems, including climate. We are responsible for the health and viability of the whole.

Implication: We need to understand and take responsibility for our organization’s contribution to the depletion and destruction of ecosystems, to climate change, and to other impacts and perturbations associated with human activities in this new era we are calling the Anthropocene.

3.1. The leader’s role in the Transformational Phase

As the imaginal cells of the new worldview within our organizations, the 21st century leaders’ tasks are to:

- Use narrative accounts to help the organization see and understand how these propositions make sense within the organization’s context. These narrative accounts can take many forms, such as sustainability reports, sustainability sections on the corporate intranet, sustainability blogs, and in- house newsletters. Today a wealth of narrative accounts exists from diverse sectors that describe how sustainability is being enacted in meaningful ways across multiple organizational contexts. A leader does not need to look very far to find accounts relevant to his/her organization’s context. His/her task is then to share or reformulate those accounts into terms and forms that work within his/her organization’s culture and context.

- Use sense-making conversations to help the organization identify where and how its actions can better align with these propositions. Because the creation of meaning is inherently a social pursuit, a leader needs to create the space and opportunities within his/her organization for conversations to take place around what sustainability means and how it manifests in tangible activities. These conversations can take many forms: workshops, working groups, advisory councils, departmental teams and task forces. Over time these sense-making conversations filter into every part of the organization and generate ideas and practices for how to enact sustainability and validate its relevance and meaning.

- Get into action by coordinating activities in ways that promote, advance, and reinforce alignment with these propositions until doing so becomes the new business-as-usual. As a natural extension of internal sense-making conversations, members of the organization identify areas where organizational activities need to change in order to align with the new propositions, and they adopt or innovate new ways to coordinate their internal and external activities to gain this alignment. As they do so they document what they know, learn, and do; and they track, monitor, measure, and evaluate the results from these new ways of carrying out activities. For example, in 2013, eighty-one percent (81%) or 403 of the Global 500, the world’s largest 500 listed public companies by revenue, reported on their output of carbon dioxide through participation in the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDC), which at that time was just over a decade old. At the time of the publication of CDC’s 2013 report, 722 investment companies, representing USD $87 trillion in assets, were requesting that the world’s largest 500 listed public companies measure and report on their carbon footprint. [xvi]

- Use narrative accounts to describe the organization’s experience and results using the new forms and meanings of these propositions, thereby validating the new terms, forms, and practices internally and externally. The burgeoning practice of producing sustainability reports is an example of how leaders are using narrative accounts to communicate what sustainability means in their organization’s and industrial sector’s contexts. These accounts then become further evidence and tools that leaders can use to advance the internal process of naming, using, and validating new terms and forms. In 2013 the international accounting firm KPMG reported that of the world’s largest 250 companies, 95% publish annual sustainability reports. The head of Climate Change & Sustainability for KPMG Americas was quoted as saying, “Companies should no longer ask whether or not they should publish a CR [Corporate Responsibility] report, even in the absence of regulatory requirements to do so. That debate is over.”[xvii]

- Act as a kind of step-down transformer within the organization, basically stepping down the high voltage of the New Story current into currency that will be socially negotiable within the organization and exportable to its stakeholders. One of the greatest challenges for the 21st century leader is to continue to hold for oneself the inspiring vision of an evolving humanity growing into the New Story—each one of us being a starborn child of a magnificent and mysterious Universe—while at the same time immersing oneself in the numerous details and challenges of daily life. Ultimately, all of one’s highest values and visions need to be translated into the language of the organization—g., that of finance, production, marketing, and brand in a business—in order to be acceptable and actionable. This, of course, is a skill-set that everyone intent on bringing about positive cultural movement towards the New Story needs to develop.

Ultimately there is nothing mysterious about how to get into action using new assumptions and concepts. This ability is a hallmark of our species and part of our adaptive toolbox. We have found that most organizations choose similar areas to enact sustainability. These are generally activities related to:

- How they use resources and materials,

- How they produce, or cause to be produced, waste and emissions,

- How they design, develop and specify product,

- How they manufacture or source product,

- How they treat people or require that sub-contractors treat people,

- How they distribute, transport, and deliver products, and

- How they give back to communities and to global society.

Getting things done is the strong suit of all the organizations that we have worked with on advancing sustainability over the last two decades; their success is built on this ability. It is one of the reasons why business is now the dominant institution on the planet. One of the tasks of the 21st century leader is to help others in his/her organization see the relationship—including both the strengths and the gaps—between their existing knowledge, creativity, and experience and their ability to solve the problems that emerge from the new intelligibility. Genuinely enacting sustainability is a serious undertaking for any organization. It requires an organization to rethink how it does everything; and to reflect on how everything it does contributes to, or takes away from, creating a more environmentally and socially sustainable future for humanity. It is as easy and as difficult as that. To do this requires creating new meaning in all of the organization’s relationships—with suppliers, customers, investors, employees, competitors, critics, and the communities that are affected by the organization’s business. Solutions may not be immediately self-evident and the approach to problems and solutions may need to be experimental at first. However, most organizations already have, or can now obtain, the skills and wherewithal to make real progress.

In the end, no single enterprise or organization can create the new system of intelligibility. How can any organization be sustainable in an unsustainable world? The social construction of the New Story is going to require countless individuals and organizations around the world acting in accord with a set of new assumptions and perceptions that are now beginning to be more widely articulated and accepted. It has already taken more than five decades, beginning around the time of Silent Spring in the early 1960s, to articulate the unsustainability narrative and to begin transforming the implications of that story into a more coherent system of meaning. It will almost certainly take at least several decades more for the majority of the world’s population to get to the point where our actions accord with a new system of meaning. This means that the work leaders do today is set in a context that extends far beyond their individual professional careers and lifetimes.

We do not know when—or frankly, if ever—the societal tipping point will take place such that Intelligibility B actually replaces Intelligibility A as common sense for how we live and act in the world. Eco-philosopher, Joanna Macy, refers to this time in history as we move from the Old Story to the New as “the Great Turning”. She comments:

The Great Turning is a name for the essential adventure of our time: the shift from the industrial growth society to a life-sustaining civilization…

A revolution is underway because people are realizing that our needs can be met without destroying our world. We have the technical knowledge, the communication tools, and material resources to grow enough food, ensure clean air and water, and meet rational energy needs. Future generations, if there is a livable world for them, will look back at the epochal transition we are making to a life-sustaining society. And they may well call this the time of the Great Turning. It is happening now…

Although we cannot know yet if it will take hold in time for humans and other complex life forms to survive, we can know that it is under way. And it is gaining momentum, through the actions of countless individuals and groups around the world. To see this as the larger context of our lives clears our vision and summons our courage.[xviii]

According to a growing number of narrative accounts from the global scientific community, such as the IPCC discussed earlier, we may not have another five decades to make this Great Turning. Signs are not yet clear whether the shift can happen more quickly than we currently imagine; or that the changes we need could indeed occur exponentially; or that humanity can figure out how we can go on together, not only with one another, but also in balanced relationship with the rest of the natural world. “The most remarkable feature of this historical moment on Earth,” Macy (2009) reassures us, “is not that we are on the way to destroying the world—we’ve actually been on the way for quite a while. It is that we are beginning to wake up, as from a millennia-long sleep, to a whole new relationship to our world, to ourselves, and each other.”

- The evolutionary crossroads

Humanity stands at an evolutionary crossroads, the confluence of shifting, contradictory, and competing stories and worldviews. To change the future, we must first imagine it, and imagination is one of the unique gifts and attributes of our species. At this nexus point, 21st century leaders are called upon:

- To imagine a plausible worst-case scenario in the a future that may extend beyond their lifetime (the unsustainability narrative), to make the necessary decisions, and have the courage and the means to take the necessary actions, to avoid it;

- To imagine a plausible best-case scenario for that same future (the sustainability narrative) and to make decisions and take actions to create it, even if we will not witness or participate in that future story; and

- To act now, in the face of incomplete information and uncertainty, even though we will not be the ultimate beneficiaries of our decisions and actions.

The late futurist Willis Harman suggested that business institutions play a vital role in this evolutionary process. He pointed out two key tasks for “enlightened” business. The first task is for leaders “to promote broader understanding, and maybe some enthusiasm about, a change in paradigm that will be good for ourselves, good for relationships, good for the environment, and good for the planet”[xix]. As the implications of the unsustainability narrative become more prevalent in global society, the unresolved tensions among our systems of intelligibility can devolve into fear: “fear of instability, of economic collapse, of mass unemployment, of an uncertain future, of the ‘crazies’ in our midst—then the one thing people will crave most is stability”[xx]. At this point the really critical task of business may be “to reassure the fearful that the needed transformation can be accomplished without a lot of social disruption and attendant human misery. The experience of business leaders can be critical at that point—assuming that they are sensitive and aware enough to play a constructive rather than reactionary role”.[xxi]

Harman submitted that the most powerful institutions on the planet need to take responsibility for the whole. In the past half-century business has become the dominant institution on the planet, touching every part of our lives. Taking responsibility for the whole is a new role for business, a new form of meaning that is not yet well understood and accepted. Harman pointed out:

Built into the concept of capitalism and free enterprise from the beginning was the assumption that the actions of many units of individual enterprise, responding to market forces—what Adam Smith called the ‘invisible hand’ would somehow add up to the desirable outcomes. But in the last decade of the 20th century, it had become clear that the ‘invisible hand’ is faltering. It depended upon consensus of overarching meanings and values that are no longer present. Given our present conditions, business has to adopt a new tradition of responsibility for the whole by defining its own interests in a wider perspective of society. Every decision that is made, every action that is taken must be viewed in light of that responsibility. This requires more than incremental adjustments; it calls for a fundamental redefinition of business as a social partner. [xxii]

“In the end,” Gergen (1994) reminds us, “all that is meaningful grows from relationships, and it is within this vortex that the future will be forged.”

Humanity has arrived at an evolutionary crossroads. Today there is an almost irresistible inertia to keep us going down the tragically unsustainable path that we are currently on. Will humanity be able to shift direction and build an irresistible momentum in time to take us down a different path, one where we forge a thriving, peaceful, and sustainable future that honors the extraordinary and evolving Universe of which we are an intrinsic part?

In the thousands of years of remembered human histories, it has been expressed in many ways in many times among many peoples that we are that being who lives between Heaven and Earth—ever torn between the god-like qualities of our highest selves and the bestial qualities of our animal selves. Never in our history as a species have we been so urgently called to live and be inspired by the qualities of our better natures; and to grow beyond the tug of our weaker selves. This is a challenge for us as individuals just as much as for our organizations and our society—because ultimately, our organizations and our societies are only expressions of us. So we come now to our evolutionary challenge—the very real challenge of our time. It is the story we are still writing together. It is that socially negotiated story that will ultimately answer the question: How are we to go on together?

REFERENCES

Berry, R. J. ed. (2006). Environmental Stewardship: Critical Perspectives, Past and Present. New York: T&T Clark International.

Berry, Thomas, (1985/86) “The New Story,” IN CONTEXT #12, Winter 1985/86. Langley, WA: In Context Institute. Available at: http://www.context.org/ICLIB/IC12/TOC12.htm. Last accessed by the writers on January 12, 2015.

Encyclopedia of Public Health referenced on Answers.com. Available at http://www.answers.com/topic/ecological-footprint. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Evernden, N. (1992). The Social Creation of Nature. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gergen, K. (1994). Realities and Relationships. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gergen, K. (1999). Invitation to Social Construction. London: Sage.

Gergen, K. (2001). “Psychological Science in a Postmodern Context,” Pre-publication draft for The American Psychologist. 56, p. 805. Accessed online at: http://www.swarthmore.edu/Documents/faculty/gergen/Psychological_Science_in_a_Postmodern_Context.pdf. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Gergen, K. and Gergen, M. Editors (2003). Social Construction: a reader. London, England: Sage Publications.

Goleman, D. (2009). Ecological Intelligence. New York: Broadway Books.

Harman, W. (1995). Transformation Of Business: An Interview With Willis Harman, by Sarah van Gelder in Business On A Small Planet (IC#41) Originally published in Summer 1995 on page 52 Copyright (c)1995, 1997 by Context Institute. http://www.context.org/iclib/ic41/harman/. Last accessed by the writers January 5, 2015.

Harman, W., (2013). “Why a World Business Academy?” http://worldbusiness.org/why-a-world-business-academy/. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Hansen, J. (1 and 2), M. Sato (1 and 2), P. Kharecha (1 and 2), D. Beerling (3), R. Berner (4), V. Masson-Delmotte (5), M. Pagani (4), M. Raymo (6), D. L. Royer (7), J. C. Zachos (8) ((1) NASA GISS, (2) Columbia Univ. Earth Institute, (3) Univ. Sheffield, (4) Yale Univ., (5) LSCE/IPSL, (6) Boston Univ., (7) Wesleyan Univ., (8) Univ. California Santa Cruz), (2008). “Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim? Available at http://arxiv.org/abs/0804.1126. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: IPCC Climate Assessment Reports are available on line at: http://www.ipcc.ch/.

International Commission on Stratigraphy, “What is the ‘Anthropocene’? – current definition and status.” http://quaternary.stratigraphy.org/workinggroups/anthropocene/. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Macy, J. (2009), quoted on her website: http://www.joannamacy.net/thegreatturning.html. Last accessed by the writers January 5, 2015.

Meadows, D. “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System” Available at: http://www.donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, http://millenniumassessment.org

Nattrass, Brian & Altomare, Mary, (1999). The Natural Step for Business: Wealth, Ecology and the Evolutionary Corporation. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Press.

Nattrass, Brian & Altomare, Mary, (2002). Dancing with the Tiger, Learning Sustainability Step by Natural Step. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Press.

Pearce, Joseph Chilton (1973). The Crack in the Cosmic Egg. New York: Pocket Books.

Percival, R. V. (1998). “Environmental Legislation and the Problem of Collective Action,” Duke Environmental Law & Policy, p. 9 www.law.duke.edu/shell/cite.pl?9+Duke+Envtl.+L.+&+Pol’y+F.+9+pdf. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

SustainableBusiness.com (2013). “Corporate Sustainability Reports Reach 86% of US Largest Companies”. http://www.sustainablebusiness.com/index.cfm/go/news.display/id/25389. Last accessed by the writers January 5, 2015.

Wackernagel, M. & Rees, W. (1996) Our Ecological Footprint. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Press.

ENDNOTES

[i] See the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, http://millenniumassessment.org

[ii] A system of intelligibility is defined here as the sum total of our notions of what the world is and how it works. It is that system of interrelated beliefs, values, constructs, and stories that renders our world understandable. It is equivalent to the German concept of Weltanschauung, or worldview, that is, what is reality to us.

[iii] 1 Chronicles 16:30

[iv] Meadows, D. “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System” Available at: http://www.donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

[v] See http://quaternary.stratigraphy.org/workinggroups/anthropocene/. A proposal to formalize the ‘Anthropocene’ as the name of the current epoch is being developed by the ‘Anthropocene’ Working Group for consideration by the International Commission on Stratigraphy, with a current target date of 2016. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.

[vi]Evernden (1992), pp. 19-20.

[vii]Gergen, K. (2001). “Psychological Science in a Postmodern Context,” Pre-publication draft for The American Psychologist. 56, p. 805. Accessed online at: http://www.swarthmore.edu/Documents/faculty/gergen/Psychological_Science_in_a_Postmodern_Context.pdf. Last accessed by the writers on January 5, 2015.