Tom Murray

PART I

Introduction: Dialogue and the Pulse of Freedom

Tom Murray

Dialogue invokes ideals of equality, participation, freedom, collaboration, responsibility, diversity, creativity, and adaptation. A central theme in the advancement of human society is the movement from rigid and authoritarian to more responsive, democratic, and thus dialogic social practices. Open, free, authentic, rich, and reciprocal communication is seen as essential to generating acceptable life conditions in our world of dizzying complexity, rapid change, global interconnectedness (Habermas, 1999; Latour, 2014; Gastil, 1993). Dialogue is not only about talking—it is a central component in problem solving and decision-making, and is a metaphor for a respectful and interactive way of being with others and with the natural world. To be in dialogue is to listen deeply and respond in integrity. However, as practitioners in fields as diverse as family therapy, management consulting, environment activism, and geopolitics are well aware, high quality dialogue and deliberation can be a very difficult thing to foster. The ideal of open, free, authentic communication includes assumptions about human nature that, it turns out, are not easily realized.

“Shadow” forces at varying levels come into play that are at odds with our ideals, including thought forms based in histories of fear, scarcity, or trauma; and oppressive social structures and power dynamics.[1] The sheer complexity of dealing with multi-faceted situations and diverse human needs and perspectives also strains human capacities and thwarts productive interactions. Deep dialogue is seen as a structure that might support people in bringing the best of themselves to the table by mitigating these problematic aspects of the lifeworld, and creating engagement contexts that support more generative and ethical collective reasoning. It is also seen as a curative and evolutionary practice for transforming people and social dynamics. Many have been envisioning and experimenting with new dialogue, problem solving, and decision making models that might support fuller access to the abundant intelligence, compassion, and creativity latent in the human condition (we review many of these later).

One leading branch of thought draws strongly from psychological and spiritual (or transpersonal) principles to suggest that what is needed are dialogue structures that support people in putting aside preconceptions, assumptions, biases, and mental filters to achieve states of more open awareness and “higher consciousness.” These models share much with traditions of contemplative practice, which use deep listening, stillness, equanimity, and inner reflection as tools of insight and growth. These contemplatively-oriented dialogue practices are also called “we-space practices” (though the term is also used more generally for any group structure). Contemplative dialogue practices aim for a radical depth in authenticity, group field coherence, and insight generation.

Clearly, this type of dialogue practice is not for everyone or every situation, but contemplative dialogue does seem to contain important pieces of the overall puzzle of generative dialogue processes. Addressing challenging problems requires more than small or medium sized groups of people sitting in a circle (actually or metaphorically) and “diving deeply” together—it requires action coordination, accurate information, extended commitment, etc. But it does seem that so much of the strife, folly, and missed opportunities of the human condition are caused by bias, negative emotion, and ignorance that could be lessened using principles borrowed from both contemplative practices and dialogic principles, and that the call to raise awareness and consciousness is well-founded, as it is about building human capacity in ways that are sorely needed in this era.

For the purposes of this article “we-space practices” are characterized by having strong dialogic and contemplative components, and can also involve action-inquiry cycles. Thus, unlike purely contemplative or purely dialogical practices, they offer the hope to support transformative development through their attention to the inter-development (tetra-emergence) of whole systems (I-we-it-its).[2]

As we will see, we-space practices can take a variety of forms and serve a variety of purposes. What they have in common is that they offer group process structures that support participants moving into states of deep interiority (“causal awareness”) and deep authentic participation and inter-listening. These states (and related developmental stages) are said to support capacities for working beneath and beyond status quo belief systems, habitual thought patterns, and routine forms of interaction. Many believe that visiting the sometimes unsettling, sometimes exhilarating, depths of these transformative territories is necessary for the creative processes of the real insight, evolutionary human development, and cultural/systems transformations that are needed to address the complex problems of the post-modern human condition. These practices promise to have exciting potential for individuals to gain deeper growth and liberation, and for groups and cultures to imagine and execute workable solutions to pressing complex problems.[3]

Integrally-informed we-space practice

Within the community of integrally-informed theory and practice[4] (the intended audience of this article) there is increasing interest and discovery regarding contemplative dialogue (we-space) practices (see Gunnlaugson & Brabant, in process; and descriptions of many projects in the section below on “Other Contemporary Contemplative Dialogue Projects”). This community has the potential to make unique inroads because it brings together models of human psycho-social development; systems theories of wholeness, emergence, and complexity; and insights from contemplative spiritual and transpersonal practices.

Integral theory has its roots in transpersonal psychology and contemplative orientations to spirituality and is stronger in its explanations of individual phenomena vs. its explanations of collective or intersubjective phenomena (though of course both are covered in Wilber’s AQAL model). Though the integral lens adds significant value to the study of intersubjective phenomena, the community as a whole is still in an early stage of assimilating work from other communities and disciplines, experimentation with novel forms, and building theory and vocabulary around these phenomena. We are in a state of great enthusiasm but relatively little theory or clarity, and the conversations can appear a bit muddled as we feel our way into increasing competence.

Integral theory has the potential to, and already has, contributed significantly to exploration at the leading edge of we-space practices, primarily through its quadrant model for holism, its developmental model of human capacities, and its unique articulation of interior and ontological depth (e.g. ground of being and causal phenomena). However one danger at this phase of exploration is jumping too quickly to conceptualization, categorization, modeling, and metaphysics, and creating a false veneer of understanding that belies the real complexity, nuance, and deep phenomenology we face in this area. This is one reason that my emphasis is on experience (phenomenology), processes, and potential practical outcomes, and I eschew or bracket more metaphysical concepts such as collective consciousness, “higher we,” “circle being,” omega point, Authentic Self, and spirit/soul—except as they refer simply to a type of experience or (fallible) intuition. This is in keeping with a post-metaphysical orientation that frames metaphysical ideas as important meaning-generative and pragmatic tools, yet sees them as problematic when used to make claims about reality (see the Appendix for a discussion on the (post-) metaphysics of we-space, and Murray (2011, 2015) on post-metaphysics and integral theory).

For integralists, the ultimate motivation of we-space practices (and all practices) is the moral/ethical imperatives of liberation, sustained happiness, and/or (Kosmic) evolution. Bhaskar formulates liberation (self-emancipation and social justice) in terms of the elimination of the demi-real—ideas and thought patterns that cause harm because they do not sufficiently match reality (Bhaskar, 1975, 1991). This line of reasoning is reflected in many themes of spirituality, human potential, and social justice. That is, the most effective emancipatory actions and systems require forms of individual and collective “shadow work,” stripping the mind/ego of systematic biases that occlude experiencing the deeper nature of things and the deeper connections between beings. In the later sections of this paper I will frame we-space practices in terms of this type of shadow work and the insights that come from exposing the demi-real to the cleansing sunlight of individual or collective awareness. Thus in addition to approaching intersubjective practices from an embodied and experiential perspective, I will describe them in terms of revealing or absenting (ablative) processes rather than as additive (sublative or transcending and including) developmental processes of increasing complexity.

Overview

This paper is written primarily for those who are first-hand explorers of we-space practices and those interested in curating or facilitating we-space encounters—and there are increasingly many of us. I want to explore this territory with you from the inside as we inquire more deeply into the nature and purposes of these practices, trying to makes sense of our experiences and intentions. Thus the paper is grounded in embodiment, pragmatics, and phenomenology (i.e. experience, not the academics of Phenomenology) as a way to guide participatory action inquiry.[5]

In lieu of “expectation management” for the reader, I will note that the purpose of this article is to survey related literature and practice in an interdisciplinary range of fields, draw conceptual distinctions and connections, and craft a few guiding theoretical principles. Though I emphasize embodiment, the treatment is more theoretical and speculative than about praxis: there are no “how to” descriptions of practices and no case study applications described. The article will probably make the most sense to those in communities of practice that use contemplative dialogue practices and have an experiential understanding of what is possible when it goes well, and who are interested in how these relatively circumscribed activities relate to larger themes.

Though this paper frames contemplative practices mostly in terms of cognitive capacities such as awareness and insight, we should not loose sight of the fact that “coming together” for any virtuous purpose is substantially a matter of the heart. Gathering, even if for a moment, with intention and vulnerable enthusiasm in the service of a higher calling is a thing of hopeful solidarity, joy, and wonder. In answering a call to embrace and dive deeply one joins hands with countless others around the globe who choose to listen to the imperatives of the heart and attune to the collective “pulse of freedom.”

The contents of this paper proceed as follows. In Part I my goal is to clarify the concept of contemplative dialogue, because, as mentioned, its theoretical treatment has been a bit muddy thus far within the community of integrally-informed theory and practice. I explore the goals, skills, and experiential elements of contemplative dialogue by decomposing it into three overlapping phenomena. I look at (1) (individual) contemplative practices, and (2) group and deliberative dialogue processes to allow us to ask What does contemplative dialogue practice add over and above these modalities? That is, why would we turn to we-space practice instead of using these more common practices?

For me, a full understanding of contemplative dialogue requires a serious focus on the phenomenology of the experience itself, and not only that but a focus on its embodied or non-linguistic, non-symbolic elements. Thus, before exploring contemplative practice and group practices I explore a third area, (3) somatic or movement-based group structures and flow-states (using ensemble improvisational dance as an example)—and I do this first because the non-linguistic non-symbolic aspects underpin the more cognitive and linguistic ones. I characterize contemplative dialogue in terms of any form of dialogue that includes an invitation into the deep interiority found in meditation and flow-inducing group somatic activities. This is how contemplative dialogue differs from group processes such as brainstorming and “conversation café’s,” that also use the power of the collective mind to support creative reasoning. Practices of deep interiority are thought to support the skills of awareness, self-understanding, and tolerance for uncertainty and paradox that are necessary for reasoning about complex multi-perspectival life conditions.

Next, I discuss the most well-known (within the integral community) contemplative dialogue practices: Bohm Dialogue and Scharmer’s U-Practice. I use these examples to explore central themes: deep interiority, sensing and presence, group process dynamics, vision logic; collective intelligence, creativity and insight. At the end of Part I I survey over a dozen contemplative we-space projects, to complete the discussion of the state of the art.

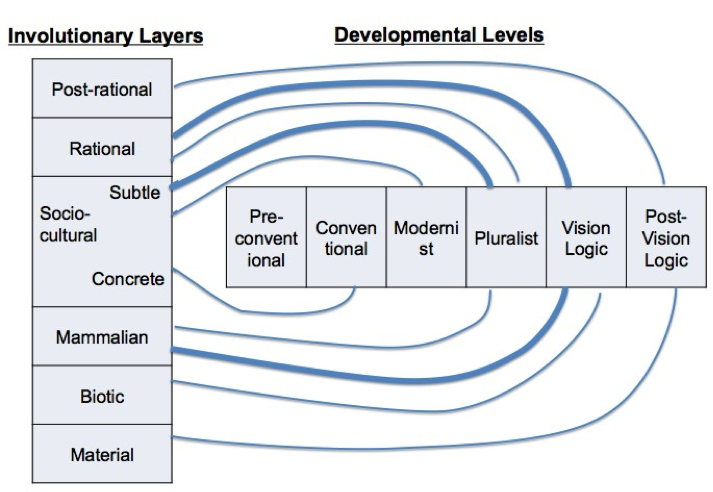

In Part II I attempt to extend the state of the art with new, if speculative, ideas, many of these building upon Bonnitta Roy’s Collective Insight model. First I propose (following Roy) that the central goal of contemplative dialogue is insight-generation that illuminates aspects of collective shadow. Next I frame insight-generation in terms of subtractive (ablative) processes of peeling away or illuminating collective biases, habits, and shadow elements (this follows Bohm’s lead). Then I more deeply discuss shadow work, first at the individual level, then at the collective level. Finally, I describe a developmental/evolutionary model of shadow work, which can be used as a framework for understanding and designing contemplative dialogue practices. This model differentiates layers of shadow material related to the stratified layers of human being: matter, life, animal, the socialized human, the rational human, and the trans-rational human. I suggest that contemplative dialogue practices can be informed by considering how shadow material is illuminated at successive layers, from the “middle out.” These are preliminary sketches of models needing further elaboration through application.

A rudimentary cultural/historical contextualization

As a preliminary contextualization of our topic, I will frame we-space practice in this historical moment (for the developed Western world) using AQAL’s I/we/it/its model.

After some decades eyeing each other suspiciously from a distance, two arms of progressive culture, (I-focused) contemplatives and spiritualists and (it-focused) activists for social justice and environmental sustainability entered into a sustained dialogue and integration—which has been ongoing now for several decades. Activists are looking more contemplatively within themselves to clean up projections and other forms of systematic bias, and to build personal capacity, presence, and integrity. On the other hand, contemplatives see the need to “come down off the mountain into the marketplace” and align with the Bodhisattva vow to become more engaged in the world.

Meanwhile, new-age spirituality is weaning itself from a mid-20th century overemphasis on narcissistic interpretations of self-liberation (“spiritual materialism”) and a reliance on charismatic teachers. There is a swelling of interest in more collective and democratic (we-focused) approaches to spirituality. In parallel, activism is also deepening its appreciation of intersubjective phenomena, developing increased empathy for both the others that it wants to help (as opposed to seeing them as oppressed others or projecting their needs upon them) and the others that it fights against (as opposed to demonizing them and denying shared vulnerabilities of the human condition). And it is developing more sophisticated approaches to group process (e.g. the Occupy Movement).

Within spirituality and religion the importance of community, care, service, and sangha has been emphasized for thousands of years, but they have been framed by conventional concrete and mythic narratives. And political activism has always emphasized the importance of grass-roots community-based approaches. But in the 21st century both spirituality and activism are increasingly informed by (“second tier”) emergent trends including: network and meshwork theory, peer-to-peer culture, deep democracy, de-centering philosophies, social networking technologies, evolutionary/developmental theories, deep phenomenology, and dynamic systems theory. These emergent trends include a more adequate understanding of participation, interaction, complexity, chaos, emergence, and transformation.[6]

Integral studies of we-space practice are very much at the forefront of these trends. Thus, we-space practices emerge at this historical moment from the integration of contemplative/spiritual (I), activist/action-oriented (it), and collectivist/participatory (we) threads in cultural evolution; informed by newly emerging metaphors for consciousness, evolution, and dynamic systems. It is an exciting time to be inquiring in this area.

2. Dance with me (us): contemplative somatics

Author’s Background

Because part of this paper takes a phenomenological approach and speaks to the experience of we-space practices, I should mention the breadth, depth, and limitations of my own experience (for example, you would not want to listen to a lecture on the topic of love from someone who clearly had little, or mostly tragic, experiences in that life-domain). Like many readers I have had numerous experiences with collective state-inducing practices including contemplative dialogue (e.g. Bohmian, Insight, and Quaker dialogues) and new-age drumming or chanting rituals inspired by native peoples and spiritual gurus; and also have experience with individualized practices that can produce unitive and sublime experiences such as meditation retreats and psychedelics (and intoxicants).[7] I consider myself still a student and journeyman in all of these things.

I have participated in we-space-practices associated with the integral community (including the EnlightenNext community’s Enlightened Communication), U-Theory activities inspired by Otto Scharmer’s work, Big-Mind activities (with Genpo Roshi, Dianne Hamilton, and John Kesler), Bonnitta Roy’s Collective Insight practice, and various on-line collective and contemplative sessions inspired by integral themes.[8] After such experiences I sometimes ask myself: what is unique, or uniquely integral or second tier, about this experience?[9] These “integral” we-space experiences have much in common phenomenologically with my other experiences in movement, contemplative dialogue, mediation, etc. And they also have something in common with more mundane collective experiences such as music concerts, brainstorming, team sports, or political rallies, in those rare moments when the more mundane activities produce expansive feelings of flow, insight, and unity. We-space-practices are indeed different than all the other types of experiences and activities I have mentioned—but describing exactly how is not easy.[10] I will first compare them to contemplative ensemble dance, because there is so much about both contemplative practice and group-consciousness experience that is somatic.

I am fortunate that my life has led me to practices and communities related to improvisational dance, where collective consciousness, we-practices, and we-states are deeply and unmistakably embodied. Through over 30 years of participation in Contact Improvisation and freestyle dancing (yes you can still find those nouveau-hippy, drug- and alcohol-free barefoot boogies in most major cities), and living in an area that is a socio-cultural hot-bed for such activities, I have been blessed with many opportunities to experience a variety of somatic practices. I will describe an idealized version of one of many improvisational movement “scores” of the type typically lead by a teacher during a workshop. Movement scores are simple rule sets that constrain options and in so doing can create a type of group coherence and flow. They also unleash creative potential through constraint (Amabile & Pillemer, 2012; Sternberg, 2006).[11] Imagine, if you can, that you are participating in the idealized movement score described below.

The Dance

We are with about 50 participants standing in a large room, having been asked by the workshop facilitator to distribute ourselves randomly in space and to settle into silent attentiveness. We are instructed to face the front wall at all times. We are told that we can move only forward, backwards, or 90-degrees to either side (i.e. moving in the four compass directions, always facing forward), and are to remain in a standing pose and not intentionally make contact with others (though it may happen accidentally sometimes). The leader instructs the group to begin with a warm-up period, asking us to move slowly, maintain awareness of safety issues and avoid bumping into others, and to take responsibility for our own safety. We are coached to use soft visual focus and heightened peripheral vision; to let our bodies be relaxed yet alert. We are like parts in a biological machine that must be well-tuned and responsive to allow the whole to function well.

Imagine that all participants are skilled movers and that this type of activity is not new for them. Through the warm-up the rules become more automatic and embodied. The leader, who is in a sense a choreographer, may add a few more suggestions or refine the rules until she is satisfied that the correct foundation has been established. The structure is then set free and no further instruction is given for a 15 to 60 minute movement score (the leader may slip in as a participant at this point). Note that this is not a serious dance activity, it is all play. Yet, as in all games played well, we hold a type of serious commitment to the form.

As the score progresses, a multiverse of events unfolds. Varied phenomena blossom in different parts of the room, and each participant has a unique perspective on the whole. Sometimes the entire room seems to be in coordinated motion—a hive or flock; and at other times the whole is composed of pockets of very different activity—an pond or forest ecology. As experienced improvisational movers, each has a finely tuned capacity to navigate the dimensions of individuality and collectivity, of leading and following. Like jazz musicians improvising, all are listening openly, responding to individuals next to them and to the whole as it manifests larger flows of movement energy. Each is responding yet also initiating, making clear decisions every moment. You experience what it might be like to be in a flock of birds or a school of fish. It is pure play and enjoyment, flow and focus.

During one period you are in a long line where bodies are moving forward and backwards like automobile traffic that pulses between being bunched up and spread out. Participants remain curious about the emergent pattern for some time, remaining focused within this sandbox in the midst of the larger playground. Because the participants in this emergent sub-collection are having fun exploring the nuances and variations of this sort of movement, no one moves sideways out of the line for a while. At another point you find yourself in the back corner of the room beside another mover, and decide to follow and mirror them as they move rather randomly through the space (while keeping with the structure, facing forward and moving front, back, left, and right). At another time you decide to remain completely still as others flow around you doing whatever they do, and you assume a panoptic kind of focus on the whole room as it flows around you. Within the full score there are a medley of temporal and spatial flow patterns containing rapid movement and very slow movement; synchronous movement and chaotic movement; mirroring movements and contrasting/oppositional movements; and both large group and small group (or duet) coordination of movement.

When the activity is complete, exhausted and blissful, you sit against a side wall and let the energy run through you until normalcy begins to return.

Though the movers in this particular score are not touching each other, this work grew out of the dance form called Contact Improvisation (enacting such scores are often part of weekend-long workshops including other movement and dance activities). Contact Improvisation is a post-modern dance form invented in the 1970’s though generative exchanges among martial artists, gymnasts, and professional dancers—with a strong influence from Eastern contemplative and mindfulness practices. Its best-known founder, Steve Paxton, has commented that “If you’re dancing physics, you’re dancing Contact. If you’re dancing chemistry, you’re doing something else.” This points to the impersonal, even transpersonal, nature of the activity. The focus of each individual is on movement and sensation, not on social relations, roles, expectations, or niceties. The pleasure derived from the flow state of collective attunement is physical and unlike the pleasure of social interaction (though social-pleasures can arise; as can both physical and social frustrations and distresses).[12]

Somatic We-spaces and Facets of Collective Embodiment

Let us now relate this experience to integrally informed we-space-practices that are not movement-based, but are instead verbal-contemplative. There is much about we-space-practices and experiences that is “embodied”—originating in pre-verbal aspects of experience as opposed to the content of discursive thought. We can draw from the movement example above both for metaphor and for precise comparison.[13] Many of the important themes are identical in the two domains, and focusing first on a somatic practice allows us to ground the investigation, to separate the embodied experience from the social elements of the experience and from the cognitive elements of the experience; and to gain some clarity where spiritual and metaphysical themes enter into considerations of we-space. Here are some of the themes that arise in collective somatic practice, which I will call “Facets of Collective Embodiment:”

· Autonomy and communion. The example illustrates the nuanced interplay between the individual and the collective; leading and following; listening and acting. One can be completely autonomous, yet still fully immersed in and participating with the whole. One is leading and following simultaneously, and experiencing the play of or dissolution of this polarity. More fully autonomous or self-authoring participants create more productive and/or flexible group outcomes.[14]· Interiors and exteriors. One can discover a similar interplay and interpenetration between interiors and exteriors—a loosening of the normal separation of self and world or self and other. Attention zooms in and out fluidly between micro and macro contexts. Events can obtain a type of enchantment or deeper meaning.· Awareness and sensitivity. The desired state is one of openness and attention. There is an attunement, sensitivity, responsiveness, and non-clinging quality to attention and intention. This quality is also called deep listening, and involves an ability to focus or direct attention as needed, while not fixating on any object. IT includes the capacity to zoom in with discernment while remaining open to taking in everything panoptically out to the periphery.· Egolessness and the transpersonal. If one is fully in a flow state in such movement scores, one’s pre-rational body-mind is making most of the decisions; there is no conscious or verbal thought involved, and no self-judgment or self-consciousness. One is not attached to or overly identified with one’s position or socially constructed relationship relative to others. This could be called a transpersonal state in which participants are coherently engaged through their raw sense of being. While not being driven by such ego-related impulses, the participant might still notice them arising in the self.[15]

· Equanimity and trust. The flow states associated with group practices require high levels of trust and surrender: trust in self, in other individuals (including the facilitator), and in the process (and, some might say, the larger whole or “the universe”). This involves a belief, or perhaps a stance forged of suspended judgment, that: I am OK—my errors and limitations are natural and acceptable (and perhaps even unwitting contributions to the whole); others are all acting in good faith; and there is, in a sense, no right or wrong, good or bad, in what happens here—it is all just “what is” as it flows from who we are. This can be as much a practice as a decision or effortless result. The trust in self supports trust in others, and vice versa; and each person’s trust adds to the overall field allowing others to drop deeply into mutual trust.

· Will and intention. Within play and improvisation there is commitment to the form and to one’s colleagues; a sense of responsibility and seriousness helps form the container within which freedoms manifest. Within the container of the structure, letting both unconscious body-intelligence and the field of the collective influence one’s choice, one can experience a kind of choice-less choice. The meaning of agency/free-will becomes problematized or paradoxical. One experiences action and decision as “just happening,” as coming through one, perhaps from within and perhaps from outside, yet not through intention and volition.

· Deep time and space. The experiences of time and space can become altered and/or heightened. The mind, no longer perseverating on past and future, roams the wide space of the now; attuned to moment-to-moment arising. One can experience emptiness yet fullness, movement within stillness and stillness within movement, and expansiveness yet one-pointedness.

· Expansive bliss. As indicated in several items above, collective somatic activities can arouse peak states of rapture, expansiveness, unity, and focus—which are characteristics of what are called “flow states” as applied to a collective activity.[16]

· Emergence, coherence, and synchronicity. Group-level patterns and phenomena emerge and dissolve at many levels (in time and in space). In such activities one can be frequently confronted with the unexpected and the improbable. There can be a sense of participating in or witnessing the magical, even the sacred. Participants can tune into the “inter-becoming” of their “inter-being” (Wight, 2013).

Importantly, there is much about peak experiences in meditation and in we-space practices that overlaps with the experience of somatic flow described above.[17] There are of course significant differences in the texture and details of, say, ecstatic dance or surfing the big wave, vs. sitting on one’s cushion to meditate or siting in a chair during a Bohmian dialogue. But all of the themes described above apply to both ensemble somatic flow states and group dialogic flow states (as both involve collectivity—not all of the themes apply to individual meditation practice).

In addition to the movement score above, one can find other group movement or embodiment activities (including Contemplative Dance, Authentic Movement, or drumming or chanting rituals) that are structured quite differently but can induce most of the phenomena listed above.

Implications of Ensemble Somatic Practices for Dialogue

What does this show us? First, as mentioned, even though dialogue is central to we-space practices, much about the experience of we-space practice is about embodiment and is pre-language (or non-linguistic). Second, I want to suggest that much of the non-ordinary or “peak” experiences of we-space practice draws on our (“lower”) animal nature, as opposed to, or in addition to, a higher or spiritual nature or a meta-cognitive capacity. Certain elements of these practices are shared, albeit in a primitive form, with social (including herding, schooling, and flocking) animals. The above elements of flow, trust, emergence, awareness, etc. are embedded potentials in the neurological structures and somatic experiences of many animal species.

Current theories of evo-socio-biology teach us that human emotional and somatic experiences are higher order or higher octave manifestations of animal-level phenomena (Panksepp, 2005; Trivers, 2002; Wilson, 1998; Pinker, 1997). That is, human phenomena such as love, problem solving, jealousy, camaraderie, gluttony…are built up from primitive animal-level phenomena. The implication is that, though human experience and capacity is not equivalent to or as simple as that of other animals, there is much to be gained by exploring how much of human nature draws upon our animal nature. What we interpret as sublime, divine, transpersonal, or esoteric experience may in part be what happens when one disengages the discursive or symbolic mind and allows more embodied pre-linguistic and pre-conscious aspects of the mind-body to predominate—embracing a birth-right that is culturally suppressed to the extent that one rejects “primitive” animal drives and experiences.

As integral and developmental theories teach us, how one makes meaning of these experiences depends in part on developmental factors. Indeed, human cognition includes layers of reflection or meta-thought that operate upon lower level phenomena, so that our experience of more primitive layers can include an awareness, reflection, or witnessing of those lower layers, and a focusing of these energies toward “higher” goals. But, as each experience is a unitary whole, it is possible to conflate higher capacities such as awareness or witnessing with the lower-level phenomena that they are aware of. I am proposing, for example, that the open sense of alert awareness and the boundary-less sense of merging with others involves taping into animal-level cognition. Regardless of whether other animals experience something only slightly similar, or strongly similar, to what we experience, the invitation is to focus on the experience at the bodily level. Awareness that one is having these experiences, or reflecting on the qualities or purposes of these experiences, constitute higher level functions. This is an important distinction in understanding we-space phenomena. As a related example, we can distinguish being or operating from a developmental level, e.g. construct-aware, from seeing and reflecting upon one’s experiences at that level, which happens at a higher level.[18]

3. Contemplative Practices and Group Processes

We-space-practices are group dialogic practices with strong contemplative elements. So, in a simple sense, we-space-practices are what you get when you add (1) contemplative practice to (2) collective/group practice and (3) dialogic practice. That is, we-space practice exists at the overlap of these three categories.[19] In this section we separately consider (1) individual contemplative practices and (2/3) non-contemplative group practices—in much less detail that our exploration of collective somatics above. These are of course very broad areas of practice and theory, and our goal here is not to cover them in any way, but to contrast them with we-space-practices to refine our understanding of the later.

Meditative Practices

I will attempt a summary of common goals among contemplative (meditation) practices as commonly understood in the West. This rough summary of a complex field is given simply as a heuristic for comparing we-space to meditative practices. The goals or outcomes of mediation practices can include the following, which I will refer to as “Facets of Contemplative Practice:”

- At a minimum a state of relaxation, and perhaps physical and psychological healing or relief from suffering (Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction, for example), as a result of simply stopping the ongoing reinforcement and reproduction of patterned thought activity. At this “Meditation 101” level, the support of pro-social or productive behavior is also a common goal.

- A set of peak experiences and refined capacities—Shinzen Young (2011) frames these capacities in terms of concentration, clarity, and equanimity. Others speak of advanced states or feelings of bliss, one-pointedness, expansiveness, emptiness, oneness, or openness; still others speak of powers or siddhis. Almost all traditions warn that all of these experiences and capacities are only markers along the way, not to be clung to. (The AQAL model contains a particular interpretation of experiences and capacities, i.e. states and stages.)

- The development of love, care, connection, empathy and compassion, which are sometimes described as natural outcomes of contemplative practice, and sometimes described as capacities to intentionally develop through contemplative practice. In many systems, the love, empathy, etc. one aspires to are objectless, open, undirected, and transpersonal.

- The liberation from or healing of mental/psychological/cultural habits, wounds, or conditioning—this includes shadow work and sometimes catharsis as a goal. (Shadow work will be discussed in later sections.)

- A deepening understanding of the nature of the self (or ego)—which ultimately includes a realization that the self, as usually understood, does not exist. It may also include insight into the nature of human suffering.

- A deepening understanding of the nature of reality and/or being (and the relationship between self and reality)—including: the realization that much or all of what we experience as real is constructed by the mind; and the realization that all phenomena are impermanent (which might mean changing, vibratory, emergent, or ephemeral).

- An experience of, understanding of, or merging with, a non-dual source—which might be interpreted as god, complete emptiness, the source of all being, etc.

There are of course other goals of contemplative practices—goals that merge with general goals of spirituality and religion—that are not as relevant to this conversation, in which I set aside metaphysical themes. These include concepts such as salvation, karma and rebirth and metaphysical theories about ultimate reality.

The point of delimiting these goals for meditative practices is the following. I propose that these are not the essential goals of we-space-practices—otherwise why not just meditate (or meditate within a sangha)? I propose that the relationship between contemplative meditation practice and we-space practice is: (1) we-space practices builds upon the Facets of Contemplative Practice; the deeper one’s experience or capacity in these facets, the more capacity one has for we-space-practices. Conversely (2) (dialogic, contemplative) we-space-practices do tend to support all of the above goals and outcomes of meditative practices, though that is not their primary aim or significance. And, importantly, there are certain aspects of the self, the ego, the shadow, and reality that are specific to social reality and interpersonal relationship, such that we-space-practices can add significantly to healing, learning, shadow-work, and capacity-building in these areas. But, as I will discuss later, even that may not be the most important outcome of we-space-practices.

Group Processes

Next I will describe what is in common among non-contemplative group practices. What group process adds that is mostly missing from both the somatic and the contemplative practices mentioned above are the social and cognitive layers that come with language and social interaction (for our purposes verbal communication is a central component of group processes/practices, though there are exceptions such as Systemic Constellation work[20]). Whereas the facets of collective embodiment and the facets of contemplative practice are found within we-space practices, and in a sense underpin them, group process can be thought of as constellationally containing we-space practice. That is, a we-space practice can be a component within, or an approach to, a larger group practice frame that sets the context and the purpose for the we-space practice.

Group practices is an even broader theory/practice field than meditation. The interdisciplinary study of group processes (and group dynamics) covers both intra (within) and inter (across) group processes; and covers all scales, e.g. two-party mediations, small group brainstorming, organizational change, large scale civic engagement, and social change methodologies.

The National Coalition for Dialog and Deliberation (NCDD, of which I am a participating member) sponsors gatherings and resources for practitioners and academics interested in a wide variety of group practices. One reason for including an overview of group-processes/practices here is to facilitate the integration of we-space practices and principles into the larger world of dialogue practice. NCDD differentiates debate, dialogue, and deliberation as in Table 1. Here “dialogue” has a rather specific meaning (in a wider sense “dialogue” includes all three categories).

Debate encapsulates the critique of status-quo communication, with its emphasis on competition, persuasion, and zero-sum assumptions. Dialogue points to more egalitarian forms of listening and inquiry. Dialogue can signal a move from (what is believed to be) objective, detached, logical reasoning to more intimate, authentic, and vulnerable conversation. One critique is that this style of dialogue can be conflict-avoidant and may aim more to make people feel good than to produce lasting effects. Deliberation in this context emphasizes situations in which a group decision needs to be made, common ground found, or stable knowledge built among participants with diverse perspectives. It requires an ability to weigh perspectives, illicit deeper truths, and make difficult decisions as a group. (Integralists will note a developmental sequence of Blue/Orange, Green, and Yellow ego development levels in these categories.) We-space practice is certainly not debate, and is mostly dialogue, but it might be used within a process that includes deliberation (as U-Practice does).Table 1: Styles of Communication

NCDD frames the space of methods as having four types of goals (visit NCDD.org for explanations of the specific methods listed):

- Exploration—People learn more about themselves, their community, or an issue and perhaps also come up with innovative ideas. (Approaches include World Café, Open Space, Bohm Dialogue, brainstorming methods.)

- Conflict transformation—Poor relations or a specific conflict among individuals or groups is tackled. (Includes Sustained Dialogue, mediation, Issues Based Bargaining, compassionate listening.)

- Decision making—a decision or policy is impacted and/or public knowledge of an issue is improved. (Includes Citizens Jury, Deliberative Polling, Formal Consensus process.)

- Collaborative action—people tackle complex problems and take responsibility for the solutions they design. (Includes Study Circles, Appreciative Inquiry, Future Search.)

We-space practice itself is mostly oriented around exploration, and can be included as a component of a larger process aimed at conflict transformation, decision-making, or collaborative action. Another NCDD frame organizes the goals of dialogue and deliberation as follows (slightly adapted, and in rough order of increasing depth/breadth/complexity): (1st order) Issue learning, improved deliberation attitudes and skills, improved relationships; (2nd order) Conflict transformation, individual and collective action, improved institutional (or collective) decision-making (one could add knowledge building and design outcomes); (3rd order) Improved community/ organizational problem solving, increased civic/organizational capacity.

Again, we-space practices are oriented to the first, but can be used in the service of the others. NCDD is a fairly practice-oriented community with some theoretical threads, and we could mention other fields of group process outside its scope, e.g. psychotherapeutic group processes, including Encounter Groups; Psychodrama, and the large body of theory and practice on collaborative learning and collaborative work.

In addition there is a vast expanse of academic and theoretical work related to group process in sociology and social psychology, which I will barely mention here, but which may be quite relevant to we-space practices. For example, readers will be familiar with group-dynamics concepts such as forming-storming-norming-performing (Tuckman, 1965). In Paradoxes of Group Life, Smith & Berg (1987) describe many of the classic group dynamics themes. They discuss belonging and scapegoating; hierarchy and power; identity and group-think in terms of interpenetrating polarities (such as autonomy and communion). Studies of “the psychology of peace and conflict” and “intergroup dynamics” may have some application to social-change orientations of we-space practices (Cohrs & Boehnke, 2008; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2013). The emerging field of contemplative neuroscience includes studies of contemplative practitioners that have implications for we-space practice (see Thompson, 2014).

We-space-practitioners and process designers can learn much from research and best practice in all of the (non-contemplative) group practice areas mentioned above, and in fact have in many instances. We-space-practices explored within the integrally informed community might have any combination of all of the goals and methods mentioned above. They might be used to support self-reflection or healing (unlearning), skill building, relationship building, mutual understanding, and idea and insight generation—all of which can later lead to actions, decision making, transformation, or large scale capacity building.

We-space-practices are usually short engagements for within-group or open-group situations, though a few practitioners, including Thomas Hübl, are using them for extended encounters, inter-group situations, and conflict transformation. Terry Patten sees we-space-practices as a vehicle for cultural change (as did Bohm, see below) and political activism, and includes the goals of uplifting and inspiring passion and commitment (Patten, 2013).[21] Steve McIntosh, Carter Phipps, and others at the integrally-oriented Institute for Cultural Evolution (www.culturalevolution.org) also focus on cultural change.

Sara Ross and Jan Inglis’ TIP framework (Integral Process For Working On Complex Issues) is a “system for comprehensive social change that citizens, officials, and public, private, & nonprofit organizations can learn to use for complex decisions and comprehensive social change” by making “complexity [and underlying assumptions] visible and manageable” (Ross, 2005; Inglis, 2007). Thomas Jordan uses developmental and integral lenses to evaluate and coordinate methodologies from across the field of deliberative methods, and has created resources and tools that organizations and citizens can use to address complex issues (Jordan, 2014). He evaluates these methods in terms of how they: focus participant’s attention, build trusting relationships, support attitudes of commitment and care, deepen understanding and perspective taking, mobilize creativity and empowerment; and lead to clear decisions and grounded actions.

These projects invoke the concept of “we space” in terms of collective action, decision making, and cultural consciousness, but are more facilitator/leader-centered than the we-space practices we concern ourselves with here. However, we can note that practices can range in a spectrum from completely egalitarian and de-centered practices (e.g. Bohm Dialogue) to more facilitated ones.

What is specific to we-space practice vs. other group processes is the movement into what I will call “deep interior space” (related to what Andrew Venezia (2013) calls “inter-subjective self-reflexivity”; and what Dustin DiPerna (2014) calls transpersonal “inter-being”). Deep interior space is the psychological and somatic space opened up in contemplative practices as applied to groups (though one can gain access to it through other means). At a group level, deep interior space has all of the elements described in the Facets of Collective Embodiment above. The group process frameworks mentioned above do not normally venture into the silent, spacious territory of deep interior space, but they can be modified with elements of we-space practice to do so. Thus the study and development of we-space practice in part involves the study and development of deep interior space in dialogic group practices. Framed in this way, practitioners have only begun to explore the vast array of possible we-space-practices.[22] One can start with any type of group process described in this section and redesign it to include experiences of collective deep interior spaces. We are just beginning to understand how to do this in a general sense, based on the most well-known we-space practices, as described next.

4. We-space Practices: Bohm Dialogue, U-Theory, and Deep Interior Space

I will start the more direct investigation of we-space-practices by summarizing two of the most well-known frameworks: Bohm Dialogue and U-Theory (or U-Process). As the reader will note from my descriptions, these serve as typical examples having key features common among most we-space-practices. Both invite participants to access deep interior space. Bohm dialogue explicitly has no outcome goals for its process, though it is designed to uncover and remediate conditioned, “incoherent,” and limiting aspects of thought and belief. U-Theory is designed to source deep interior space and then produce insights that lead to action.

Bohm Dialogue

As described by renowned physicist David Bohm in his texts On Dialog and Dialogue: A Proposal, Dialogue is a process for countering the fragmentation, incoherence, and conditioning of thought (Bohm, 1980, 1986; Bohm et al., 1991).[23] Participants sit a circular formation with no explicit roles or hierarchy, no rules per se, and no given topic or agenda. The convener notes the start and end of the period (3 hours in my experiences) as their only official actions. Though there are ‘no rules’ there is a definite structure, and a few guidelines, which new participants are introduced to before the official session start. Though the process is open and emergent, there are certain things that it is explicitly not: it is described as not being a debate (or even “discussion”), therapy group, or conflict resolution session. The primary principles are:

- Proprioception of thought — an attention to the feeling-tone and somatic aspects of thought; an embodied awareness of thoughts, thoughts-precursors and feelings as they arise.

- Inquiry — An ongoing inquiry into one’s own assumptions and biases (and what today we would call shadow elements) that might be influencing one’s own thoughts, beliefs, feelings, desires, and aversions.

- Suspension — suspension of speech and reactions (i.e. to reflect on thoughts and impulses before deciding to manifest them to the group); suspension of certainty of one’s ideas; and suspension of judgment or assumptions (suspension of disbelief or certainty), in the service of wider or clearer understanding. (Also suspension of one’s usual patterns, which might mean speaking more than usual if one is shy, or less if on is extroverted.)

Other guiding principles and suggestions might be offered, such as relaxation and acceptance of what arises; using observation of the breath or a body scan for somatic awareness; or the suggestion that one should talk to the group or to the center and not become engaged in back-and-forth discussion between two individuals. It might be noted that there may be long silences and that these can be experienced as rich rather than tense moments; and that displaying trust and positive vulnerability help create a container of deep intention.

Bohm dialogues have much in common with traditional Quaker Meeting circles and also with Native American Council formats, within which there is an invitation to “speak from the heart,” to speak what is most deeply True in the moment, or to let Spirit speak through one. Bohm spoke of “impersonal fellowship,” an early framing of what we might now call transpersonal space. While some related group process formats may be more interested in creating compassionate connection or en-spirited flow states, Bohm was specifically interested in generating insights—about self but more importantly about cultural conditioning. He saw Dialogue as a method for teasing out, observing, and gaining wisdom about mental conditioning that distorts our personal and collective understanding of reality:

“Dialogue, as we are choosing to use the word, is a way of exploring the roots of the many crises that face humanity today. It enables inquiry into, and understanding of, the sorts of processes that fragment and interfere with real communication between individuals, nations and even different parts of the same organization.” (Bohm et al., 1991)

Bohm saw Dialogue as a microcosm of society, therefore diversity within the group was important, and conflict was not to be avoided (nor resolved, but just observed). He suggested that “pervasive incoherence in the process of human thought is the essential cause of the endless crises affecting mankind” and he was looking for methods to create coherence of thought within and between individuals:

Dialogue is a powerful means of understanding how thought functions…In Dialogue, a group of people can explore the individual and collective presuppositions, ideas, beliefs, and feelings that subtly control their interactions…It can reveal the often puzzling patterns of incoherence that lead the group to avoid certain issues or, on the other hand, to insist, against all reason, on standing and defending opinions about particular issues…Dialogue is a way of observing, collectively, how…unnoticed cultural differences can clash without our realizing…It can therefore be seen as an arena in which collective learning takes place and out of which a sense of increased harmony, fellowship and creativity can arise. (IBID)

As phenomena that emerge out of chaos and indeterminacy, each dialogue takes on a unique character. A three hour dialogue can be like a mediation retreat in that one observes phases of contrasting engagement, boredom, inward focus, outward focus, confusion, frustration, and excitement. The experience of each participant is unique, though at times it appears that many in the room experience very similar or resonant states. A group’s journey of speech interlaced with silent presence can move through choppy rapids, meandering discursions, rapid sprints, and open still waters; with bursts, swings, and pulsations emerging from different areas of the circle. A strong sense of the group as a unit, or a feeling of collective energetic vibration, can emerge. One can feel like an organ within a larger living whole; or like one’s speech is one of the many voices within the head of a collective being. These are not metaphysical claims, but attempts to describe the phenomenology as I (and others) have experienced it.

I cannot find that Bohm explicitly references Eastern contemplative practices much in his description of the process (though his dialogues with Krishnamurti show that there was indeed influence), but his Dialogue process was perhaps the first to apply many of the concepts found in meditation to group dialogic settings. Our Facets of Contemplative Practice are echoed in Bohm’s work. Parallels with the Facets of Collective Embodiment are also readily apparent. The themes of: individual and the collective, awareness and sensitivity, egolessness and the transpersonal, equanimity and trust, emergence, coherence, and synchronicity, phenomenology and flow—all are clearly present in Bohm Dialogue experience (or in a peak Bohm Dialogue experience). “Proprioception” of thought is a direct pointer to embodiment.

Gunnlaugson (2014) offers a “critical retrospective” of Bohm’s approach, and notes that in practice it often does not live up to its potential. It can “produce disorienting dilemmas and confusion for groups” and dialogues can be prone to “obscure forms of philosophizing…[and participants can] get tangled up in their meta-processes” (p. 32. I have witnessed these phenomena myself in Bohm dialogues on many occasions). He says that Bohm’s model also has an “underdeveloped awareness of how to work with creative emergence in conversation” (especially as compared to U-Theory). I believe that all of these problems are the result of that fact that Bohm developed his model several decades ago, with little related theory to build upon; and also that the process works more as intended when participants are at higher ego developmental levels, which Bohm did not anticipate.

U-Process

Otto Scharmer’s U-Process/U-Theory is perhaps the most well-known group-process framework within the greater integral community (also called Generative Dialogue, Scharmer, 2007; and see Senge’s et al.’s related Presencing model, 2004). U-theory updates Bohm’s work in several ways, as it (1) was birthed within a milieu of more sophisticated understanding of contemplative and intersubjective practice and benefits from a few decades of cultural learning in these areas; and (2) is oriented to grounded pragmatic applications in organizational development/learning, servant leadership, and spiritual activism (overlapping with trends toward contemplative practice and “spirit in the workplace;” and also including the dynamic systems approaches to leadership).

U-Theory situates the space of contemplative dialogue explored by Bohm in terms of a wider model that moves in a “U” from everyday (often problematic or limiting) dialog and reasoning, into the deeper spaces of awareness explored by Bohm, and finally back up to harvest the emergent insights and capacities in experimental (“prototyping”) participatory action. As with contemporary cybernetic metaphors, the model includes ongoing feedback cycles bringing information from the “real world” into the mind/spirit spaces of contemplation. The entire process is seen as periodic, moving between surface level action/dialogue and deep contemplative presencing as each influences the other. The model can be used recursively or fractally, as individual hours-long U-Process meetings can exist within a larger U-based processes that move a group into more open, unknown, and exploratory territory and back out into harvesting insights over a period of weeks or months (even possibly at more than two nested levels; and the fractal nesting can include relational/group nesting as well as temporal nesting).

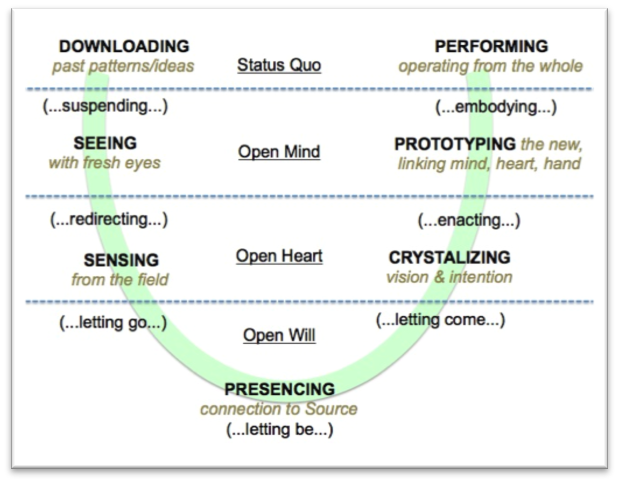

Figure 1: Scharmer’s U-Theory

U-Theory is illustrated in Figure 1, which illustrates successive moves toward depth or involution (seeing, sensing, presencing) and emergence or evolution (crystalizing, prototyping, performing). U-Theory is discussed in depth in Gunnlaugson (2007), and Reams (2007), and we give only a cursory overview here. Quoting from Reams (p. 242):

…This creates a total of seven cognitive spaces: downloading, seeing, sensing, presencing, crystallizing, prototyping, performing/ embodying. From this Scharmer calls for “a new type of social technology that is based on three instruments that each of us already has—an open mind [IQ], and open heart [social/emotional intelligence], and an open will [spiritual intelligence]—and to cultivate these capacities not only on an individual but also on a collective level” [Scharmer, 2007, p. 40]. The essence of presencing is described as our two selves (past and future) talking to each other.

Thus, in terms of this paper, we arrive at our first truly integral/integrative practice. The above descriptions of somatic group practices, meditation, and Bohm dialogue were isolated activities focusing on I and We experiences that were disconnected from any larger context (i.e. from any concrete actual larger context, though they do frame the work in terms of more global human phenomena). U-Theory encompasses I/We/It/Its aspects of reality, has a quasi-developmental (depth-oriented) model of process that deals with both time (process phases) and depth; and incorporates both reflection and action at individual and collective levels.[24] All this makes it an integral or second tier practice (though its incorporation of developmental levels is weak—see Reams, 2007).

U-Theory shapes a narrative explanation of the path from surface encounters and preconditioned modes of being into ever deeper modes of reflection and release, arriving at a still point, and emerging with insight and transformed presence into the world of action. This narrative matches perennial archetypes of the transformative journey, yet frames them in terms modern organizations can assimilate, and includes levels of depth consistent with contemplative and spiritual practices. In this paper we are primarily concerned with what happens at the bottom of the U, as we focus on contemplative dialogue practices rather than larger principles of prototyping and systems change.

Letting Go, Be, and Come; and Sensing the Future

U-theory frames its process in terms of letting go and letting come; and some also add “letting be” to point to the bottom of the U. Letting go and letting be point to processes and states of opening, release, trust, and surrender referred to in meditation and in Bohm Dialogue. The letting be is not a state of bored or laissez-faire emptiness but rather a vibrant alive open presence. Letting come is the emergence of content from deep interior space that can manifest as creativity, vision, new intentions, enthusiasm, insight, etc. It is only through experimental and playful interactions with the world, setting up feedback loops and learning from mistakes, that we learn and increase capacity (in what has been called “failing forward”)

In (always non-facilitated) Bohm Dialogue one experiences waves of relative stillness and activity arising chaotically (though the group takes some time at the beginning to settle in). In U-Process, there is an intention (and facilitation support) to systematically move from “normal” types of thought and dialogue, through ever-deeper levels of letting go and presencing, and then back up into more enactive ordinary states. The quality of we-space experience seems to depend on the depth of the letting go/letting be/presencing. The most fruitful processes will spend enough time at enough depth, as opposed to dipping into it briefly and occasionally.

U-theory has a particular way of situating time (which, roughly, it shares with integral theory, especially its “Evolutionaries” branch). Scharmer: “sensing shifts the place of perception to the current whole while presencing shifts the place of perception to the source of an emerging future—to a future possibility that is seeking to emerge” (Scharmer, 2007, p. 163).

This is an advance over Bohm’s framing, which focuses on the experience of the now and vaguely suggests that the process should lead to transformation. Scharmer’s injunction to “act from the future that is seeking to emerge” (p. 8) activates a search space within the empty but alert mind (see “seeking” and “still-hunting” in Roy, 2014) that primes for possibilities that are both possible (as opposed to fanciful) and associated with one’s moral instincts. It “facilitates the surfacing of a living imagination of the future whole” (Scharmer, 2007, p. 195). Scharmer says

every human being [has two selves:] the person we have become through the journey of the past [and the] dormant being of the future we could become…our highest or best future possibility…[We] can evoke an active resonance with either field…The essence of presencing is to get these two selves…to talk and listen to each other, to resonate, both individually and collectively. (Scharmer, 2007, p. 196)

Causal Collective States and Vision-Logic

As mentioned, we can assume that deeper traversals into the bottom of the U engender more powerful insights and actions. The deep interior spaces opened up in practices such as Bohm dialogue and U-Process can involve all of the Facets of Collective Embodiment above, including experiences of transpersonal autonomy-within-communion, deep trust and equanimity, choice-less choosing, euphoria, and enchantment. We-space phenomena can be described in terms of the “gross, subtle, and causal” categories of experience or “states” used by Wilber (2006) and elaborated upon by O’Fallon (2015). In collective somatic (i.e. group physical) experiences these phenomena arise mostly in relation to gross or concrete modes of interaction. When people are engaged in linguistic/symbolic modes of participation such as dialogue they are called upon to reflect on more subtle modes of being, such as thought processes, assumptions, social emotions, and shadow—as they arise in the moment. Furthermore, in deep interior space one becomes aware of the contours of awareness itself, and of the meaning-making process itself—which is called causal awareness.[25]

Thus, in we-space practices the phenomenological aspects of the Facets of Collective Embodiment relate to subtle and causal object of awareness, as well as gross objects. The felt-sense of the state experience is not necessarily different, however. As Wilber (2006) notes, a given state of consciousness can be experienced from different developmental levels, while additional objects of awareness and interpretations are available at each successive level.

Venezia distinguishes the “subtle we space” as operating “on the inter- and intra-personal subtle boundaries that make up our personalities,” from the “causal we space [of] shared awareness and ‘compassion as awareness’ [which includes an] interpenetration and mutual emptiness of boundaries and categories” (2013, p 11-12, 23).[26] Venezia’s continues with “it may even be fair to say that awareness, love, and presence are the mind, heart, and body of causal realization” (p. 24).

Drawing from O’Fallon’s (2015) and Kesler’s (2012) work I would propose that the causal state can be described as objectless awareness, objectless seeking, and objectless compassion—in terms of the body, mind, and heart (and the it/I/we of sacred presence). Roy’s notion of still-hunting captures the states of objectless awareness and objectless seeking, and within contemplative studies one can find descriptions of objectless compassion (loving kindness with no single recipient) as a general state experience. Casual level We-space practice might be described in terms of establishing the conditions for the senses, the mind, and the heart to roam with super-fluidity through the widest and deepest spaces of possibility that a group can muster.

The causal realm is one where paradoxes emerge and negative capability and construct-aware reasoning are needed to make meaning of the variety of perspectives one becomes aware of (O’Fallon, 2013). In the description of collective somatics, it was clear that the experience itself could only be described with paradoxical language such as autonomy-within-communion, the interpenetration of interiors and exteriors, and choice-less choice (action within surrender). Because this type of paradox is an outcome of the discursive mind’s attempt to make sense of experience, there is no problem here for the dancer in movement.

But causal we-state practices involve collective insight and meaning-making—shared through language. At the causal level conceptual boundaries become more fluid and one becomes more aware of the metaphorical limits of language. For example, a thing or idea can seem both inside (or contained by) and outside (or containing) another. The experiences can include a profound sense of both emptiness and fullness; detachment that co-exists with compassion; awareness that blends laser-like focus with wide-angle panopticism; everywhere is here, the past and future are now; and boundaries between the conscious and unconscious become more fluid. Making sense of these experiences and ideas requires that one use construct-aware (vision-logic) capacities.[27]

Roy (2014) describes the phenomenology of advanced practice (or “ritualized inquiry”) within the causal realm using evocative terms such sensory clarity, the aesthetic experience of rightness (or gnostic truth-sense), authentic chaos, participatory lucidity, and multi-paradigmatic play. Not all (and not many) we-space encounters will have these properties, and in the final section we describe an involutionary model that suggests some developmental prerequisites.[28]

Other Contemporary Contemplative Dialogue Projects

A number of contemporary experiments and models of contemplative dialogue practice have emerged (many independent of the integral community), inspired by ideas from Bohm-dialogue, U-Theory, spiritual activism, and theories of collective consciousness. These are depth-treatments of group process that aim for personal and collective transformation by including dissonance-producing deconstructive/ reconstructive phases that challenge egoic patterning and cultural norms. For example, M. Scott Peck uses concepts such as discipline, chaos, emptiness, and contemplation in his transformative model of True Community and spiritual development (1987, 1997). Arnold Mindell’s Process Work and World Work use dialogue and facilitated group encounter to access “primary process,” the “dream body,” “spiritual power,” and “sentient essence” through powerful chaotic group work that exposes sources of pathology, shadow, privilege, and oppression (Mindell, 1995, 2002). Thomas Hübl uses the terms “transparent presencing,” “transparent communication,” and “radical honesty” in describing the modes of vulnerable, authentic, contemplative dialogue he facilitates to support personal and cultural evolution (2011). In Saniel Bonder’s Walking Down in Mutuality framework for relationship-activated self-realization includes a dialogic “green lighting” processes that brings “profound compassion and radical acceptance” to contemplative encounters (Bonder, 2005).

Gary Steinberg and Gregory Kramer’s Insight Dialogue (www.metta.org, and see O’Fallon & Kramer, 2008) is an extension of Buddhist insight meditation into intersubjective space. Its focus is on the “unfolding wisdom” arising from tranquil mind and heart, right-speech, and compassionate mutual inquiry. Though it is not described in terms of development, evolution, or spirit (and thus has a non-metaphysical bent), its injunctions and principles have significant overlap with other we-space practices. These injunctions include: Commit, pause-relax-open; listen deeply and trust emergence (i.e. non-attachment); notice inter-reactivity and judgments and surface assumptions; and share background thinking and speak the (your) truth.

Ria Baek and Helen Titchen Beeth’s Collective Presencing model (2012) is a circle practice that invokes many of the themes mentioned above, including: opening up the senses, the mind, the heart, and the will; observing and honoring what is; surrender to the future potential; listening to the soul’s calling; embodiment of the authentic self; growing awareness of complexity and interrelatedness; discerning intuitions through subtle sensing and deep listening; integrating shadow; suspending judgment and embracing diversity; impersonal love; and “sense and act form Source on behalf of the whole.”

Probably the most extensive study of we-space practices to date is Andrew Venezia’s (2013) thesis. He describes we-space practices as historically new forms of “inter-subjective self-reflexivity,” that are needed because, as a species “we must grow up [and find ways] of coming together…without compromising our uniqueness [in] full autonomous participation in deep community” (p. 4). He speaks to the importance of “establish[ing] environment[s] of earnestness, trust, sincerity, intimacy, and vulnerability between participants” (p. 36). Included in his research is a analysis of interviews with leaders within the community of we-space practitioners. His analysis reveals themes that substantially overlap with those described above, authenticated through the illuminating first-hand descriptions of experienced practitioners and teachers.

We-space inquiry is moving beyond the work of individual theories/leaders into community-based movements and structural (fourth quadrant) support systems. Dustin DiPerna and the WePractice community are building a type of spiritual community of practice for “relational-spiritual practice” and “co-mindfulness” (see wepractice.org and DiPerna, 2014). From the web site: “we support each other’s awakening and development by bringing intense and welcoming awareness to the way we relate. We focus on what is happening now: inside us, between us, and around us.” These processes draw from what was learned in Andrew Cohen’s community using a process they call Enlightened Communication (Cohen, 2004; also “intersubjective enlightenment”).[29]

Two of the longest standing programs to deeply incorporate concepts from we-space practice are the trainings and workshops offered by Next Step Integral (Stefan and Miriam Martineau at nextstepintegral.org) and Pacific Integral (www.pacificintegral.com). Pacific Integral’s Generating Transformative Change (GTC) program has an “emphasis on the qualities emerging at later stages of development.” GTC workshops are multi-year trainings that build “transformative containers” that “integrate various practices of state development, including meditation, awareness practices, and subtle energy work. [They] work with polarity and paradox in a variety of contexts [and use] various psychological and interpersonal practices to develop capacity to work with shadow, projection, and relationship dynamics.” (Fitch, Ramirez, & O’Fallon, 2010; and see Ramirez, Fitch, & O’Fallon, 2013).[30]

PART II

5. Emerging Themes in We-Space Practice

I have offered a multi-perspectival exploration of the phenomenology and facets of we-space-practices, and discussed how they are described and used in contemporary contexts and communities. Let us go deeper into the questions of “what are the intended goals and outcomes of these practices?” and “what do we know about the factors that contribute to success?” Above I discussed two emerging themes: sensing into the future, and causal we-states. Below I will discuss several additional themes in contemplative dialogue practice: collective intelligence, insight generation, shadow work, heart-based wisdom development, and eliminative/ablative vs. additive/developmental models of spiritual growth.

Some practical metaphors for thought processes.

It can be useful to use science-oriented and brain-oriented metaphors to investigate we-space practice, as these metaphors are accessible to a larger segment of progressive culture vs. more metaphysical or spiritual framings. Thought processes and ideas (including, information, knowledge, meaning, and creativity) can be described in terms of connections (relationships or associations). What is connected can be as small as a neuron or as large as a paradigm; and we can use this framing to speak about individual thought and collective thought at various scales.

Thought and perception can be understood in terms of the momentary “firing” or activation of neurons, concepts, or ideas. Belief, habit, and skill can be understood in terms of “wiring” or stable connections between things in the mind (or body-mind-soul). Experience is about firing. Learning and development are about wiring. In terms of AQAL theory, states involve firing and stages involve wiring. Both firing and wiring are about associations between things (nodes, ideas, neurons, etc.), and, according to common parlance “nodes that fire together wire together” (strengthening associations through repeated use) and nodes that are wired together (i.e. are associated in the mind) will fire together (in cascades of association and patterns of reinforcement).

As we elaborate on in the section below on shadow, the mind/body also contains blockages or inhibitions that prohibit or obstruct connections between ideas (or nodes). Discussions of shadow usually focus on problematic obstructions that are the result of painful or traumatic experiences (that the mind resists revisiting). However, the mind/brain can be thought of as having two major functions: connecting/associating information, and filtering information. One could not function if one had to process the massive amounts of sensory information available at every moment; and the massive set of possible connections that the mind might make among that information and between that information and memory. So reducing and filtering information/connections is an important mental function.

Some of the filtering is related to shadow processes, which may have had an adaptive function in the past but now is maladaptive to a thriving life. Also, information can be filtered to reduce complexity, for example, when first learning to drive a car one can not coordinate conversation and tuning the radio which focusing on driving, but after mastery one no longer needs to filter these externalities and desires out. At a deeper level we could say that certain types of filtering are built into cognition and even genetics, for example, humans can only perceive certain frequencies of light and sound.

Because occlusions and filters can be diminished or removed, and detrimental ideas can be inhibited, there is the important potential for un-learning. Growth (cognitive, emotional, and spiritual) thus involves both learning and unlearning. Most models of development, such as Hierarchical Complexity Theory and subject-object theory, involve creating higher level meta-connections that transcend and include. Processes of reflection and witnessing also involve the growth of such meta-level processes. In contrast, some aspects of development involve unlearning and the removal of either connections (e.g. beliefs and habit patterns) or obstructions. These relate to modes of letting go, freeing of awareness, allowing what is, and the opening of perception and compassion that are referred to in our descriptions of contemplative and we-space practices.[31] We will extend these principles to the level of the collective in a later section.

Collective Intelligence, and Creativity