Alexander Malakhov

Alexander Malakhov

Translated from Russian by Eugene Pustoshkin

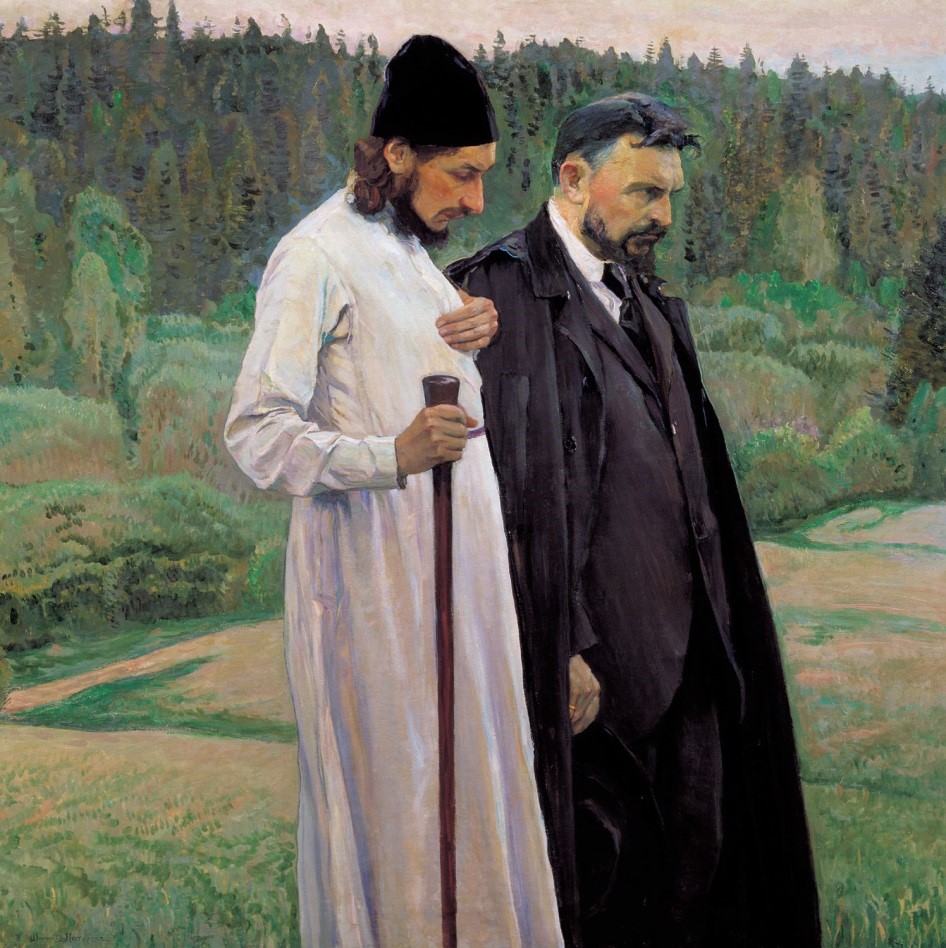

Those philosophers, who disagreed with the new regime but stayed in the country, suffered tragic fate. One characteristic example of that is Pavel Florenskiy (1882–1937), who was known as “the Russian Leonardo da Vinci.” His first book The Pillar and Ground of the Truth, written when he was 26, made him one of the leading thinkers of Russia. He was a man with an encyclopedic scope of knowledge; he received education in mathematics; he knew dozens of languages—from Ancient Greek to Farsi to Sanskrit; and he, in his own paradoxical way, united elements of arts and poetry, geometry and physics, magic and theology, in his works. He was constructing his own, profoundly mystical, version of the metaphysics of All-Unity and Sophiology. After the revolution, Florensky stayed in Russia and, in addition to his philosophic studies, worked in physics and engineering, wrote a monograph on dielectrics, and was directly involved in the project of electrification of the country. Despite his numerous merits to the Soviet regime, in 1933 he was arrested, sentenced to 10 years of GULag, and in 1937 was executed (shot to death).

Illustration: Philosophers Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov, a painting by Mikhail Nesterov (1917). Florensky is on the left.

Another philosopher-activist (filosof-podvizhnik) and major expert in aesthetics of Antiquity—and also, secretly, a monk and defender of Christian mysticism—Aleksey Losev (1893–1988) was, just as his wife, sentenced to camps for his book Dialectics of Myth. During serving his sentence he almost lost his sight. Twice as tragic is the case of the wonderful historian of philosophy and proponent of All-Unity Lev Karsavin (1882–1952): he was sent from the country into exile in 1922, and, later on, he was invited to become a professor of, at first, the Lithuanian University, and, then, the Vilnius University. After the Baltic states were overtaken by the Soviet regime, he was fired, arrested, and sentenced (at the age of 67) to ten years in prison camps, where he died of tuberculosis.

The philosophers, who were forced to leave the motherland after the revolution, continued their work all around the world—from America to China. France became the primary center of the philosophic immigration: here the last abode was founded by Sergey Bulgakov, Nikolay Berdyaev, Semyon Frank, Vasily Zen’kovskiy (1881–1962), Nikolay Losskiy (1870–1965) and his son, a prominent theologian and pioneer of “the neo-Patristic synthesis” Vladimir Losskiy (1903–1958), and many other thinkers. Each of them deserves a separate essay, but here I can only briefly touch their still-relevant importance.

Sergey Bulgakov’s contribution primarily lies in creation of a detailed teaching about Sophia—some scholars consider it to be the most important and original contribution of Russian-speaking authors to world philosophy. Sophiology can be seen as a universal framework in which new meanings are acquired by theology, ontology, and the entire body of human knowledge. Furthermore, Bulgakov was a notable proponent of imyaslavie—a radical mystical movement of Russian Orthodox Christianity, which insisted on the inseparable connection between God’s Name and His energy. In youth this philosopher was under the influence of Marxism, but later he overcame it—this is reflected in the collection of essays From Marxism to Idealism—while not losing his interest in worldly issues, such as building a just and flourishing society. In 1906, he was even elected as a State Duma deputy, as a “Christian socialist.”

Nikolay Berdyaev’s spiritual path also included a Marxist period. However, it was still in his years as a university student that he discovered an imperishable importance of religion (“religion, despite the fluidity of its content, is an eternal and transcendental function of consciousness”) and denied all reductionist worldviews. He quickly became a leading figure among the proponents of “the new religious consciousness,” but in 1913 the Czarist government sentenced him to exile in Siberia for his article that he wrote in defense of Mount Athos’ monks, the proponents of imyaslavie. In his immigration years to Germany and France, Berdyaev led an active life where he was personally acquainted with the key philosophers of the West, including Max Scheler and Oswald Spengler, and he was also nominated for a Noble Prize in Literature seven times. Usually, Berdyaev’s philosophy is characterized with the term “Christian existentialism,” however, despite the central place that freedom has in his thought, any label would rather limit than unpack his legacy.

It is even more difficult to characterize Semyon Frank’s philosophy, whose main works were published after he immigrated. It is no doubt that it lies in the general stream of All-Unity, sometimes coming closely to panentheism, but it is more thoroughly and fundamentally developed and in a more sophisticated way than in any other Russian philosopher. Whether we look at his ontology, epistemology, ethics or philosophy of science—everywhere Frank’s assertions still retain their relevance and fascination with their beauty and brevity.

Bulgakov, Berdyaev, and Frank are, perhaps, the most famous representatives of Russian philosophy in exile. After their death, the fame of being the leading Russian philosopher went to Nikolay Losskiy, the founder of intuitionism and a brilliant systematic philosopher. It is noteworthy that while in youth he was excluded from gymnasium (university-prep school) for propaganda of atheism, and yet in his mature years he became a prominent defender of religious world contemplation and mystical feeling. Among the numerous other thinkers of first rank, Boris Vysheslavtsev (1877–1954) developed “the philosophy of heart” and “ethics of transformed Eros,” and Georgiy Florovskiy (1893–1979), a brilliant theologian in whom allegiance with the Orthodox Christian tradition, combined with openness to ecumenism.

Russian philosophy is unique in that, when it lost its homeland, not only did it not die and dissolve in the intellectual currents of 20th century, but managed to keep its unique distinctiveness, flourished with new power, and, finally, returned to Russia after the fall of the Communist regime.

About the Author

Alexander Malakhov, M.S.W., is an integral scholar-practitioner & PhD Researcher at Pacific National University (Khabarovsk, Russia). His main interests include Integral Theory, world philosophy, relationship between religion and science, altered states of consciousness, and human liberation. He is the founder of “Quadrants: Integral Lab” and an Associate Editor of Eros & Kosmos (see: http://eroskosmos.org/english). Contact email: alex@malakhov.link