Ian Roth

It is commonly recognised that language is a reflection of culture and the reality portrayed by that culture. The reverse of this relationship, despite being less often considered, is no less impactful. The ways language is used serve to create patterns of thought, beliefs, behaviours, cultures, and, ultimately, realities. Wittgenstein claimed that the limits of our language are the limits of our world (68). Though the veracity of this claim continues to be debated, it provides insight into our reliance on language. At the very least, the omissions of a given language make the ideas it fails to address less accessible and communicable; it’s most rehearsed pathways preference certain destinations over others.

Taking a critical approach to language is not new, nor is the understanding that it is far from a neutral, value-free tool. Yet, despite this, the question of how the non-neutrality and implicit values of a language might be embraced and employed to create and support a thriving human system seems absent from the collective conversation. The goal of this paper will be to make the case for asking and addressing this question, arguing that the stances historically taken with regard to language use and evolution have been insufficient to support future human well-being. It will contend that language is an unexplored and rarely exploited leverage point capable of producing systemic change—that a thriving human society needs a language of well-being to support it. This point will lead to an exploration of how an idealized language might be envisioned and what some of its comprising elements might be. Finally, the question of how linguistic evolution can be made tractable will be discussed.

Brands of Linguistic Activism

Attempts to influence the evolution of language can generally be categorized in two ways. First, there is what Ackoff described as the inactive approach (22-24). Such efforts are characterised by the desire to preserve the language that currently exists and have been known to degrade into reactivity. This approach is best epitomised by the French Ministry of Language and its officially delegated responsibility to preserve the French language—a directive that often places it in conflict with the global creep of English and the evolutionary nature of all language.

The second category of linguistic activism is, to once agor to introduce the use of new or alternative words that reference phenomena in what is considered a desirable way. An example of this is the current trend of universities embracing gender-neutral pronouns such as ze and ey in the hopes of creating a more equitable, less potentially alienating linguistic environment (BBC).

As history shows, the first of these approaches is, always in the long-term, and typically in the short-term, doomed to failure. Efforts to stop change are just another kind of pressure acting to promote it. They may affect the final course taken by evolution, but they can do nothing to halt the process itself from occurring. The latter form of linguistic activism has a much better record. And while it is still one marred by an abundance of failures, this is how the process of evolution functions. There are always more dead-ends than there are ways forward. But, the problem to be addressed first is not how to make attempts at linguistic activism successful; it is how to make their outcomes more powerful and meaningful.

Linguistic Leverage Points

With regard to the linguistic environment we inhabit, words are akin to the furniture. Just as a lounge chair can be replaced with a recliner or even a bean bag without fundamentally changing the character of the space in question, any number of words can often be used in substitution without changing the overall meaning being communicated. This is not to discount words entirely. Words can be powerful leverage points, but for this to be the case, the focus cannot be the words themselves. The present-day United States struggles with this—the use of historically racist words has the potential, almost regardless of the relevant context, to turn those using them into pariah. Yet, this strict proscription of racist language does not equate to a lack of racism. Changing a word can, but often does not, stimulate a meaningful change of mind.

It is, however, the contention of this paper that language can be a powerful leverage point in creating and sustaining social change. While the record of linguistic activism is spotty, the record of human flight prior to 1903 was much worse. Perhaps it is not the desire to create change through language that is problematic, but how the road to that change is imagined.

The work of Keith Chen is both the impetus and the foundation for the investigations embarked upon by this paper. Chen is a comparative economist—a researcher seeking to understand how and why economic practices differ among the world’s societies. Among his findings, perhaps the most relevant to the current inquiry is that, controlling for elements such as tax codes, earnings, cost of living, family size, trust, and cultural attitudes about saving, populations whose primary language lacks a future tense (e.g. I go to the park tomorrow) save 39 per cent more of their income by retirement than do populations grammatically required to employ a future tense (I will go to the park) (692).

This difference extends to a number of other future-oriented behaviours. Future-less populations are ‘24 per cent less likely to smoke, 29 per cent more likely to be physically active, and 13 per cent less likely to be medically obese’ (692). Chen’s analysis shows that the linguistic practices of future-employing populations prompt them to perceive their future selves as distinct entities. Conversely, for future-less speakers, the future and the present are indistinguishable—who they will be is who they are now. The future tense creates a gulf between what is and what will be. And, in that we can live only in the present, destined to never experience the future, this gulf is unbreachable. We are never forced to face the reality of our future selves for they are always out of reach, occupying an unknown though, we imagine, certainly preferable terrain on the other side of the gulf.

As revealing as Chen’s work is, its importance is not a function of its descriptive ability. It is a systems understanding of causality that gives these findings their potential potency. Chen’s analysis of the data suggests that the linguistic feature in question has a causal force of its own, one unconnected to the effect of culture. And while this is a useful finding in that it substantiates the causal potency of linguistic structures, it is also analytical and mechanistic in nature. It is a finding based on an effort to isolate the elements in question. Incorporating Chen’s causal findings into a holistic understanding of how these elements function, suggests the following set of relationships:

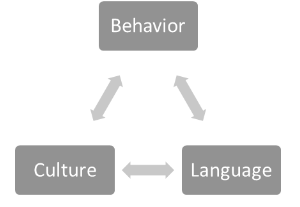

Figure 1

Language and culture directly inter-determine one another while each is also simultaneously engaged with behavior in direct co-creation. Each of these relationships defies the linear causality model; none of the three elements should be considered primary. They arise simultaneously; it is the relationship in which they are involved that should be considered primary (Macy 72; Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski and Flowers 193).

Given this, it is clear that language will change as a result of cultural and/or behavioural shifts. With regard to these processes operating in reverse, Chen states that his findings are “…consistent with the hypothesis that languages with obligatory future-time reference lead their speakers to engage in less future-oriented behaviour” (721). Thus, the intuition behind linguistic activism is, as previously admitted, sound.

If we conceive of the language with which we interact as an element of our environment, this finding is consistent with Lewin’s equation: B = ƒ(P, E)—behaviour equates to a function of the person and his or her environment (4-7). And, considering this, it must be acknowledged that not all environmental changes are equally influential. Just as the relationships between language, behaviour, and culture are primary, it is more elucidative to understand language as primarily consisting of relationships. An individual word is nothing but a symbol, at some point arbitrarily associated with that which it symbolises. Consequently, there is very little content to a word and, predictably, very little transformational potential associated with changing one. It is the relationship between the words that makes deep, rich content possible. The word ‘will’ cannot itself account for the differences presented in Chen’s research. But the space this word creates in the relationship between the subject and the action can. If changing words is like exchanging one piece of furniture for another, then changing the grammar that organises these words is akin to reworking the layout of a space. It is a feng shui approach to communication and ideas.

Changing physical structures as a way to change the workflow, interactions, and experiences of a space’s inhabitants is a well-established intervention strategy in the field of architecture. It also has a long track record as an intervention strategy employed in other systems. The flow of traffic is produced and re-shaped by the design of the environment our vehicles occupy. We add stop signs to change how the agents interact; we build new roads to encourage certain flows. A language, like a system of roads, will tend to promote the use of certain routes from point A to point B. By making certain destinations more accessible, it will make them more frequented and popular. While it is entirely possible to reach locations poorly serviced by a road system—even to go off-road or carve a new path—doing so requires more time, effort, and care. The necessity of such extra commitments contributes to the low frequency with which such locations are accessed.

When it comes to grammar, the majority of roads are off-limit. Even if an English speaker wanted to refer to something he or she was planning to do without inserting the ‘will’ gap, to do so would be to encourage stigmatization, signalling what others would interpret as a sign of poor education rather than an informed, intentional omission. In this way, cultural conditioning makes us the guards in our own prison. Before addressing how this dilemma might be circumvented, I will investigate some of the outcomes that might make doing so worth the effort.

The focus of this discussion will now narrow to the English language. As the presumptive first global language in human history, it should be assumed that English, more than any other of the world’s languages, will help to shape the global culture towards which we are heading.

Finding a Linguistic Lighthouse

The next stage of this inquiry will begin with the guiding question of idealized design. If, tomorrow, we awoke to find a blank slate where we once had a creeping lingua franca, how would the language we chose to fill that space function? In order to answer this question, it is helpful to identify a set of desirable outcomes we can agree to pursuing—an ethic to guide the design process. A number of interdependent concepts seem fit for this role including sustainability, thrivability, well-being, and development. Taking these, and any other concepts that fit into and support this constellation, as the guiding values, the project of imagining an idealized language has the requisite orientation.

Any effort on my part, or that of any other individual, to present a finalised blueprint for the ideal language would be both presumptive and doomed. All sociolects—languages as they exist at the social level—are emergent phenomena the measure of which is unavailable to any single contributing agent. In the case of language, this challenge is layered back upon itself many times for, while an individual’s understanding of the sociolect he or she participates in will, by definition, be incomplete, there also exist the array of languages about which he or she can say little if anything of substance. Additionally, language is inter-determinant with context. It reflects, informs, and creates the realities with which its speakers find themselves faced. I am unable to speak in detail about the situation in which most of humankind finds itself, nor can I predict how that situation will change over time. The contextual nature of language means that the idealized imagining of one is work to be done by the swath of that language’s stakeholders in an ongoing, never-finished manner.

For these reasons, I will limit myself to a few suggestions meant to act as impetus and background for an ongoing process of generative inquiry. These suggestions will be based upon my experience as a learner of Japanese teaching learners of English.

Issues with English

I the centrepiece

One of the first aspects of English that seems both important and unique is the stress it places on the first-person subject. Much of the time, Japanese speakers will omit explicit identification of a subject in their sentences preferring, instead, to infer the subject from the context and intonation. Directly translated from Japanese, the sentence ‘Do you like dancing?’ would be something closer to ‘Is dancing liked?’, or perhaps simply, ‘Like dancing?’. This contextually reliant approach is made possible, in part, by the intricate levels of formality that characterise the language. Even in a setting with multiple participants, the level of formality employed by the speaker identifies the person to whom he or she is speaking.

On this point it is worth noting that English is a much more democratic language. While formal words and expressions exist, they do not infuse the language or serve nearly as essential a function. Yet, English can, and should, be accused of putting too much focus on the individual. It is the only language that not only compels the use of an ‘I’ equivalent but insists on its being capitalized in every instance. This includes close relatives such as French, German, and Spanish, all of which employ an ‘I’ equivalent without also demanding its context-independent capitalization (Winter). By contrast, English does not compel the same treatment for ‘you’ or, somewhat suspiciously, for ‘we’—a designation that includes ‘I’. Given this, it should be expected that native English-speaking populations would demonstrate relatively higher levels of individuality as opposed to collectivity. And this seems to be what the data suggests. The world’s most individualistic countries are, in order, the United States, Australia, Great Britain, and Canada, each of which are mainly populated by native English speakers. The least individualistic English-speaking countries according to this index are Ireland and South Africa standing at 15th and 20th out of a total of 76 countries (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov 95-97).

Quite simply, English makes ‘I’ the central, primary, fundamental subject in relation to which everything else exists, and it does so by fiat. English learners are punished with red X’s and reduced scores for doing otherwise. It does not seem a coincidence that ‘I’ so resembles the number ‘1’, the building block with which all whole numbers are composed. English implicitly regards the individual as the basic unit; groups are perceived as the combination of individuals with no equivalent recognition that individuals might be understood as the combination of the groups with which they identify.

This embodies a perspective, not a truth, and one which can justifiably be critiqued for its role in producing and promoting our current, unsustainable paradigm. Given the scope of human history, the individual that is identified by ‘I’ is a new concept—one tangled up with the rise of romantic love during the Medieval Period (Campbell 8:00-12:30). Granted, it is an important concept for our evolution as a species, representing a crucial step in the progression from a tribal mindset towards what Robert J. Lifton has called the ‘species self’ (221-223). Our future thrivability depends to some extent on our ability to hold the tension between ourselves as individuals and as members of something larger; it requires us to live the paradox of individual collectivism and of collective individualism. Such a cosmology does not have room for the capitalized ‘I’.

We the Unaccounted For

Keeping with the focus on pronouns, it is also worth pointing out that English has no easy way to reference the human species as a group that includes the speaker. The word ‘we’ comes closest, but often falls prey to context. This seems like exactly the kind of pronoun and, thereby, pattern of thinking that We should endeavor to promote given that thrivability is a species-level concern. Additionally, it is strange that the rules of English grammar demand Earth be prefaced by ‘the’. It was the author and organizational consultant Carol Sanford who pointed out to me the objectifying effect this had on what is not only a living system, but likely one that enjoys some form of consciousness (personal communication). We should not address Earth as though it were a well-known monument. To do so is more than inaccurate—it contributes to the distance we feel from a system in which we are embedded, abetting our mistreatment of it and, ultimately, our self-destructiveness.

Problematic Possessives

Thinkers ranging from Wittgenstein to the Buddha have understood the self as an illusion of language, but this is far from the only illusion it casts. English speakers apply possessive pronouns to just about everything imaginable claiming semantic ownership of animals, land, and other people. The modern, Western-derived, private property-permitting concept of ownership is not reflective of any intrinsic, objectively verifiable arrangement present in the world; it is not a fact about the world, but a description of how we function in that world. It produces and is produced by a social reality comprised of shared beliefs about what can be owned and what ownership entails. It is beyond the scope of this paper to make claims about how property as a concept should best be understood and employed. But pointing out that current English usage obfuscates a collective fiction that governs how we interact with the world is within that scope. So, too, is suggesting alternatives.

A possessive-less language is not an impossibility. The Maasai language makes a distinction between ownable and unownable things. Russian, Hungarian, Finnish, and a number of other languages employ existential clauses such as ‘at me, there is a book’ instead of ‘my book’. Arabic does not employ genitive clauses saying, ‘book the boy’ instead of ‘the boy’s book’. An English language of sustainability might register the statement ‘this land belongs to us’ grammatically incorrect preferring instead ‘we belong to this land’ or, better, ‘we are of this land’. ‘My brother, my partner, my child’ would be appropriately formulated ‘a brother, partner, or child to me’. An idealized English need not be political, but it should strive to be truthful so that the political arguments that follow are not grounded from the start in falsity.

To Say ‘Be’ or Not to Say ‘Be’

Another grammatical area to consider is how English currently encourages the use of ‘be’ verbs. It is grammatically correct to say about a person who stole something once, that he or she is a thief. This construction, while accurate in its accounting for something that happened, suggests an ongoing state; it implies that the person in question has continued up until the present point in time to engage in the behaviors characteristic of a thief. It is interesting to consider which descriptions employ such constructions, and which require additional qualification. A person who engages in extra-marital intercourse once is a cheater for life. A person who appeared in every episode of a no longer running reality television show is a former reality TV star. This says a great deal about North America’s prevailing value system and about the actions that are assumed to define us forever. It raises the question of how a person can be expected to better themselves when they are so readily, and for perpetuity, placed inside a linguistic box.

Carol Dweck makes an equally important point about how we speak to children. Saying to someone that they are good or smart can, with respect to a healthy mindset, be quite damaging as it assumes that traits like goodness or intelligence are locations in the spectrum of being that can be reached and occupied indefinitely or, even more troubling, that they are static, innate qualities, neither able to be lost nor gained (116-126). In this way, such descriptions obfuscate the truth that goodness is contingent upon an ongoing commitment to performing good acts. There is no terminus, no finished state for goodness or smartness. As Aristotle is often misquoted as having said, “Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit” (Durant 87). Extending this point, just as the construction ‘to act compassionately’ is more salutary than ‘to be compassionate,’ so too is it more accurate. Senge et al relate the story of how Buckminster Fuller was fond of presenting his hand and asking his interlocuter, ‘What is this’. Invariably, the person would respond by identifying it as a hand, to which Fuller would respond, “What you see is not a hand. It is a ‘pattern integrity,’ the universe’s ability to create hands” (6). Thus, in the words of Alan Watts, “Just as the flower is a flowering of a field, I feel myself to be a personing, a manning, a peopling of the whole universe” (7:45- 7:58).

Be is also a problematic word due to manner in which it is applied to experiences of the world. It is common for English speakers to describe their experiences by employing language such as, ‘that movie was scary.’ The ubiquity of such constructions serves to disguise their descriptive faults. Conscious experiences such as being scared or feeling something is heavy are not objective characteristics of the world that are merely encountered by the observer. Consciousness itself is an emergent property, and the experiences that populate it are the result of a dynamic relationship between subject and object, observer and environment. This relationship is so entangled that a more accurate understanding would do away with the not entirely benign convenience of this bifurcation. An accurate language would not allow the kind of labelling we currently practice, for it is tantamount to a linguistic shirking of responsibility for the part we play in creating the experiences we have of the world.

Dealing with and preventing the issues caused by this linguistic practice is one of the main goals of Non-violent Communication (NVC). NVC regards it as imperative that we move beyond such labelling practices both as speakers and as listeners (Rosenberg 15). In the above example, an NVC formulation would be something akin to ‘While watching that movie, I felt scared.’ The difference in this example may seem paltry, but a further comparison should help to demonstrate the importance of the difference being discussed. Consider the kinds of outcomes that would be promoted by the statement ‘You are scary’ as opposed to one such as ‘When you yell, I feel scared’. The shift from describing what and how things and other people are—as though these qualities were innate to them—to describing how you felt in response to a situation and its stimuli is a potent one, yet it is also a surprisingly difficult practice to make habitual. This is mainly due to the relative ease of employing the labelling shortcut provided by the English that reliably populates the everyday world.

Articulate Articles

I would like to finish with two related, generative suggestions. The first is that the grammatical rules surrounding the and a should be re-evaluated. The manner in which the is commonly used is grammatically correct, but factually inaccurate. This is due to the limiting function is accomplishes. Combinations such as ‘the cause’, ‘the answer’, and ‘the outcome’ have legitimated the idea, in practice and thence comprehension, that causes, answers, and outcomes are typically singular and mutually exclusive of other possibilities. This perception has been so reinforced that it is now common for arguments to arise over which of two entirely compatible and, at times, even mutually supportive causes is the ‘true’ one. Simply by changing the article employed, a different understanding vis a vis complexity can be engendered. The cause of gun violence in the United States is not the availability of guns, the lack of support for mental health issues, inequality, or the depiction of violence in media. It is an emergent property that can only be attributed, with any accuracy, to the entire mess in which these causes are entangled. No one of these is the cause and, thus, each is a potential leverage point. Answers, causes, and outcomes exist interdependently among many, not alone and disconnected. Adhering linguistically to this may do much to help those engaged in stalled debates to find a way forward.

Something similar is true for but and and. The word but both effectively discredits what came before it and cuts off unexplored avenues of potential synthesis. Uri Alon describes how innovative science demands a leap into the unknown; that it requires exactly the mindset that refuses but in favor of and (7:50-6:50). He is speaking to something Niels Bohr encapsulated with the words, ‘How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress’ (Moore 196). Elsewhere in the exploration of creativity, the widely known first rule of improvisation is to respond to suggestions with ‘yes, and…’ in order to support and build on the flow of ideas.

The usage of a and and being suggested would not constitute a redesign of English. These usages are entirely consistent with the grammar of English as it currently exists. They are not, however, consistent with how it is employed or how it is taught. And this raises the question of how linguistic activism might be undertaken on the scale proposed.

Backdoor activism

The English classrooms of the world cannot always be held accountable for the English that is spoken by those who attend them. Ideolects—the language unique to an individual—are products of experience (Beckner, Blythe, Bybee, Christiansen, Croft, Ellis, Holland, Ke, Larsen-Freeman & Schoenemann 14-16). The language each of us is exposed to serves to legitimate the patterns that emerge over the course of those exposures, and out of these patterns emerge the grammatical guidelines distributed in school settings. Even should every English class in the North America begin stressing the use of a and and as the new grammatical norm, the exposure to English constituted by in-class time pales in comparison to the out-of-class exposure common among native English speakers. Family, friends, and media contribute more to the formation of native speaker ideolects than do language teachers. But, it may be possible to circumvent this problem by focusing, instead, on non-native populations whose ideolects are more heavily influenced by their classroom-based exposure.

It is estimated that there are around 400 million native English speakers worldwide. By contrast, the estimated number of people currently studying English as a second or foreign language is one billion (ESL Market Statistics). With many traditionally English-speaking countries experiencing birth-rates close to or below what is needed for replacement, the former number is relatively stagnant with the likelihood of shrinking in the future. As might be expected, with the rising standard of living in countries like China and India, the latter number is growing.

Already, and increasingly, outnumbered by non-native speakers, the pressure to adapt linguistically to a diversifying English language is on native speakers (Morrison). The sector of air travel has already begun adjusting to the evolutionary pressures being exerted by this linguistic diversification. Air traffic controllers and pilots of all nationalities are expected to use Aviation English, a 300 word, often grammatically distinct form of English. It was designed and implemented to overcome a variety of linguistic difficulties experienced by non-native speakers attempting to communicate in English (Payne). This is an example of linguistic evolution resulting from pressure exerted by non-native populations. The need for native speakers to relearn English as it is employed by the non-native speakers with whom they interact constitutes an opportunity not only to ensure that communication is possible, but to improve the medium employed in service of that communication. As the source of the English language’s evolutionary pressures shifts from native to non-native speakers, it will be possible to transform the nature of that evolution from primarily happenstantial to significantly conscientious.

What is being suggested, then, is that one of the most potent and easily leveraged avenues of linguistic change are English as a Second Language (ESL) and English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms. These can act as seeding sites for linguistic evolution. The consensus among researchers at this point is that language acts as a Complex Adaptive System (CAS) (Beckner et al 14-18; Kirby 679-681). Assuming this to be true, the robustness of the English language and, as previously discussed, the cultures and people who employ it, relies on the variety of options available within that system (Ashby 191-192). The self-organizing nature of language should not, in an attempt to design something ideal, be denied. Rather, seeds of variety should be sown in language classrooms around the world. EFL and ESL students should be given the opportunity to bring some of their native linguistic practices into their English idiolects.

While we generally respect the need for a mixture of linguistic integration and differentiation among native speakers, the practice applied to non-native speakers until this point has been one of enforced similarity. Linguistic activism and, perhaps more accurately, linguistic leadership in a situation where the CAS in question is subject to homogenizing forces, requires the allowance and introduction of heterogeneity. And, though this paper began by invoking idealized design, the perspective afforded by this approach can only serve as a point of comparison, not as a step-by-step guide. The functional goal should be, not an ideal language, but a better one. As with any evolutionary process, the prevailing form of English at any given stage will not be the best possible form, but one which proved itself a better in-context fit than the previous form—even if only slightly so.

Of course, none of this is meant to suggest that organizations and native speakers not involved in ESL/EFL are helpless to contribute. The dominant sociolect is an emergent property of its constituent, accumulated ideolects (Beckner et al 14-15). Thus, as with all systemic change, at some point and to some degree each of us must be able to see our part in creating that change (Senge et al. 45). We must understand and accept our dual roles as both the recipients and creators of the systems in which we are enmeshed. In keeping with this, we must recognize that our quotidian choices are “the secret that lies at the heart of nonviolent social transformation…” (Schwartz 7). Each individual linguistic choice contributes to the emergent language and determines, to a not inconsequential extent, whether it will be a language of exploitation, waste, and selfishness or one of well-being that contributes to the creation and support of a sustainable, thriving future.

References

Ackoff, Russell. Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems. John Wiley & Sons, 1974.

Alon, U. “Why Truly Innovative Science Demands a Leap into the Unknown.” TED Talks, 2014, https://www.ted.com/talks/uri_alon_why_truly_innovative_science_demands_a_leap_into_the_unknown. Accessed 3 August 2018.

Ashby, W. R. Variety, constraint, and the law of requisite variety. E:CO Issue Vol. 13 Nos. 1-2, 2011, pp. 190-207.

Beckner, C., Blythe, R., Bybee, J. Christiansen, M. H., Croft, W., Ellis, N. C., Holland, J., Ke, J. Larsen-Freeman, D. & Schoenemann, T. Language is a complex adaptive system: Position paper. Language Learning 59, December, 2009, pp. 1-26.

Campbell, Joseph. “Love and the Goddess.” Interviewed by Bill Moyers. The Power of Myth. PBS, 1988.

Chen, K. M. The effect of language on economic behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. American Economic Review 103(2), 2013, pp. 690-731.

Durant, Will. The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the World’s Greatest Philosophers. Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Dweck, Carol. Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press, 2000.

ESL market statistics: How many people learn English? ESL http://esl.about.com/od/englishlearningresources/f/f_eslmarket.htm. Accessed 10 July 2017.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw Hill, 2010.

Kirby, Simon. The Evolution of Language. In the Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, edited by R. Dunbar and L. Barrett. Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 679-681.

Lewin, Kurt. Principles of Topological Psychology. McGraw-Hill, 1936.

Lifton, Robert J. The protean self: Human resilience in an age of fragmentation. Basic Books, 1993.

Macy, Joanna. Mutual causality in Buddhism and general systems theory. State University of New York Press, 1991.

Moore, Ruth. Niels Bohr: The man, his science, and the world they changed. The MIT Press,1985.

Beyond ‘he’ and ‘she’: The rise of non-binary pronouns. BBC, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34901704. Accessed 8 July 2017.

Rosenberg, Marshall. Nonviolent communication: A language of life. 2nd ed., PuddleDancer Press, 2003.

Schwartz, Stephen A. (2015). The 8 laws of change: How to be an agent of personal and social transformation. Park Street Press, 2015.

Senge, P., Scharmer, C. O., Jaworski, J., & Flowers, B. S. Presence: Human purpose and the field of the future. Crown Business, 2004.

Weisbord, Marvin R. Productive workplaces: Dignity, meaning, and community in the 21st Century. 3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, 2012.

Winter, Caroline. (August 3, 2008). “Me, myself and I.” The New York Times, 3 August 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/03/magazine/03wwln-guestsafire-t.html. Accessed 27 June 2017.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Routledge Classics, 1961.

About the Author

Ian M Roth currently works as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Foreign Studies at Meijo University, located in Nagoya, Japan. He earned his Ph.D. in Organizational Systems program from Saybrook University. In addition to questions of linguistic evolution, his research interests include educational systems design and emergence-based pedagogies.