Ryan Nakade & Devon Almond

Ryan Nakade

Devon Almond

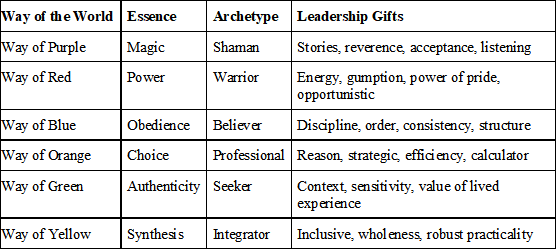

The ways of the world evolve as we evolve. Our lenses of life shift as we shift. Each way of the world has its place, its value, and its limitations. Each way of the world also offers its leadership gifts. While leadership, itself, is as developmentally diverse as our inner and outer worlds, for the purpose of this article, we draw on conventional leadership scholars, like Jim Clawson (2008) and Warren Bennis (2009), as well as integral philosophy to view leadership in terms of managing energies—first within ourselves, then in others, so that we might become a more integrated person, bringing together disparate elements of ourselves, in order to more fully and freely offer our gifts in and to the world.

Just as we mature as people, we also mature as leaders. To paraphrase Bennis in his book On Becoming a Leader (2009), leadership isn’t much different than the process of becoming a human being. In adopting this developmental orientation to leadership, we illustrate largely through first-person perspectives how the leadership gifts of premodern, modern, and post-modern consciousness, collectively known as first-tier consciousness and correspondingly as the first-tier way of leadership, offer a strong and flexible foundation to simultaneously address the wicked problems and awe-inspiring possibilities in ourselves, cultures, societies, and nature through second-tier consciousness and the second-tier way of leadership. The ways of the world that we describe in this article reflect those of Spiral Dynamics as developed by psychologist Clare Graves in the 1970’s and then systemized by Don Beck and Chris Cowan (1996).

These ways of the world offer lenses of life that we can use to understand ourselves and others, so that we can bring our deepest, highest most generative selves into community. These ways also offer us lenses for other people to bring their most robust contributions into community. While each way of the world embodies significant gifts, it’s important to note the postmodern insight that we look at and listen differently depending on our respective lens of consciousness. This is to say that what we see depends on how we think. Drawing on the understanding that our “worldview (or vision of life) is a framework or set of fundamental beliefs through which we view the world and our calling and future in it,” (Olthuis, 18) we suggest that our dominant way of the world literally shapes what we see with our eyes and how we listen with our ears. Of course, our eyes and ears represent the primary senses through which the self meets the world.

To demonstrate, consider how two different ways of the world—in this example, the Way of Purple and the Way of Orange—interact with very same phenomenon. The vitality and reverence for the nature of wilderness so prevalent in the Way of Purple and its archetype, the Shaman, is clearly misplaced in the mechanistic, post-industrial age of the Way of Orange and its archetype, the Professional. Unlike the subjective reverence for the nature of wilderness inherent in the Shaman archetype of the Way of Purple, the Way of Orange looks and listens to the nature of wilderness as an object that is separate to self. For the Way of Orange, nature is exploited for its scientific value or consumed as a vitamin or experience. Here, the nature of wilderness is viewed in terms of our environment or surroundings. In stark contrast, for the Way of Purple, nature is conflated with the core of the self. Of course, both of these are valid perspectives. Yet, as integral philosopher Ken Wilber (1997) aptly tells us more than we are a part of nature, nature is a part of us. Knowing that nature is at the core of humanity can awaken us to see how the nature of wilderness might shape the civilization of humanity. It is here that we both begin (Way of Purple) and conclude (Way of Yellow) our exploration of the spectrum of leadership gifts.

This article is structured in a way that illustrates each of the ways of the world largely through the personal experiences of the primary author, which are supplemented by relevant experiences of the secondary author. For efficiency, these perspectives aren’t differentiated in the article. Given both of our connections to Big Island, Hawaii, we draw heavily on relevant happenings on the island to illustrate the various ways of the world.

First-Tier Way of Leadership

The Goddess Awakens: Volcanoes, Pele, and the Power of the Way of Purple

![]()

Pele, the Hawaiian Goddess of the Volcano, has awakened. Erupting from the earth through newly opened fissures on the east side of Hawaii’s Big Island, Pele is once again making her presence known. The Big Island is no stranger to these periodic cataclysms with the last one occurring in November 2014. With this recent eruption, Hawaiian residents are once again reminded of Pele’s terrifying and awesome power. With homes destroyed, properties decimated, and rescue missions underway, many would think that the people of Hawaii would be psychologically and emotionally devastated by such a catastrophe. However, despite the destructive intensity of these eruptions, many peoples of Hawaii have maintained an equanimous attitude of surrender. For these people, Pele is the true ruler of the island. With this understanding, Hawaii’s residents are reminded that they are but humble visitors passing through her domain.

Of all the Hawaiian Gods and Goddesses, none is more widely feared, and yet revered, as the Goddess Pele. Goddess of the volcano and fire, destruction and transformation, Pele symbolizes the raw power (known as mana) of Hawaii’s ancient lands. Growing up on the Big Island, I witnessed first-hand the cultural pervasiveness of Pele’s legend—from the mystical stories of old timers to superstitious tales of magic and curses. But her main reference was always to the volcanoes of Hawaii, and to its full-of-awe, awesome, and destructive power, knowing that at any moment we could be engulfed by her scintillating fury.

Hawaiian mythology epitomizes magical consciousness, or the Way of Purple consciousness. The leadership gifts of the Way of Purple—stories, reverence, acceptance, and listening—illuminate an immanent vitality communicated by its archetype, the Shaman. In the Way of Purple, the world is alive and animistic, teeming with spirits and brimming with sentience. With the Way of Purple, place matters. Indeed, place broadly, and the nature of wilderness more specifically, is the terrain of transformative practice. Nature contains intelligence, consciousness, and power, and can commune directly with our human psyches. For the Way of the Purple Shaman, every object in nature contains intrinsic meaning and emanates this reverent aliveness for behind every stone, tree, or waterfall lies a God or Goddess ready to speak directly into our souls.

This magical re-enchantment of the world, this reverence stands in stark contrast to our mechanistic modern day conception of nature as a heap of inanimate resources to be appropriated for human use. It goes without saying that in our current day of mass media, over-communication, consumer cultures, and increasing pervasiveness of technology, we have lost touch with this primordial realm of our ancestral past. But somewhere, buried deep down in our human psyches, lies the dormant mana of the magical world, ready to be tapped into and awakened once again.

This is part of what makes Hawaii a unique place on planet earth: It is a place where modern and post-modern life and ancient legends collide. Hawaiian residents’ responses to the volcanic eruptions show that Pele and the Way of Purple in general is still very much alive and active in the Hawaiian cultural psyche. The benefits of such a worldview are revealed in their attitude of serene acceptance towards such a calamity. Beneath the broken hearts from watching their homes erupt in flames lies a deep understanding that this is Pele’s home. Acknowledging that she is the true ruler of the land, there is nothing more to do than to surrender completely and accept that Pele is “taking back what is rightfully hers” as one gentleman said.

Pele is telling her story and we are listening. Like a tracker observing animal trails, or an elder listening to the winds to inform the group’s movement, the direction of who is telling and listening is distinct from modern and post-modern cultures. Applied to leadership, the Way of Purple might wake us up to deeply reflect on Parker Palmer’s (1999) inquiry: Is the life you are living also the life that wants to live in you? We might also reflect on the role of listening in our work. Palmer points to vocation not in terms of a goal to be achieved, but as a gift to be received. Whereas vocations involve listening to and responding to callings, jobs and careers involve the subject of ourselves pushing into the objective world of employment opportunities. In other words, we might ask: Who is telling and listening to the story of our lives?

American poet David Wagoner (1976) beautifully demonstrates this directionality in his poem, Lost: “Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you are not lost. Wherever you are is called ‘Here,’ and you must treat it as a powerful stranger. (You) must ask permission to know it and be known. The forest breathes. Listen. It answers. I have made this place around you. If you leave it, you may come back again, saying ‘Here.’ No two trees are the same to Raven. No two branches are the same to Wren. If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you, you are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows where you are. You must let it find you.”

In the pre-rational oneness of undifferentiated oceanic consciousness, the Way of Purple creates a sense of reverent intimacy, which at times, parallels an almost erotic connection with the world of inanimate nature. This sense of reverence and intimacy crowds out the sense of impersonal dread that is a produced by our modern, mechanistic worldview. The terrifying volcanic eruptions are not just a random geological event ready to destroy your private real estate, but a deeply meaningful expression of Pele’s power with her spirit dancing and her blood boiling. Turning the mechanistic “it” into an intimate form of “you” curtails the cold, impersonal fear of the object, softening the experience of loss as we are enraptured by Pele’s mana and coruscating beauty.

In writing this, I am reminded of the oneness that precedes duality and the multiplicities of the relative world expressed in the Tao te Ching (1989): From one comes two, from two comes three, from three comes 10,000 things. Without first becoming one with nature in the first-person perspective (e.g. presence), it is difficult for me to be in relationship with nature in the second-person perspective (e.g. attune) and to integrate these into a third-person perspective with reverence (e.g. witness). I can deeply feel into this truth when I am on the beach with my feet buried in the sand. As the ocean waves cover my feet, I sink deeper into the sand. I am one, present with the ocean. Then, as the waves, head out again, as waves do, I mourn as my beloved departs. I am in relationship, attuned, with the ocean. A moment later, my feet are again covered in water. Now I am subject, witnessing, water as object. With reverence comes serene acceptance.

Growing up in Hawaii, I am often asked if I surf or love the ocean. Shamefully, I admit that I have a paralyzing fear of sharks which has kept me out of the waters for most of my life. That suddenly changed when I started talking to a wise Hawaiian elder named Vivian. Vivian explained to me that for her, the shark is an ‘aumakua or guardian spirit (usually in the form of an animal). As she described the mana of the ‘aumakua, I felt I was absorbing the Way of Purple by osmosis, and her magical transmission left me a changed man. Instantly, my fear of sharks was cut by at least half. At my next trip to the beach, I debuted my newly awakened Way of Purple lens by praying to the ‘aumakua of the shark and enjoyed a great swim with minimal amounts of anxiety. The shark was no longer an impersonal killing machine as portrayed by movies like Jaws as I now had an intimate relationship with the shark; it was an ally, a brother, a friend.

The magical essence of the Way of Purple allows us to commune with the divinity inherent within nature and deepen our reverent relationship with the animate and inanimate world. True to the name of magical thinking, it is not a rational operating system, but a deeply intuitive, reverent world intimately felt by our primordial psychic history. With my shark story, I was always rationally aware of the extremely low statistical probability of a shark attack, but that never allayed my phobia because that fear wasn’t rational to begin with. It could only be touched by something just as irrational, which was the newly awakened enchantment of a magical worldview.

How can we excavate this dormant aspect in all of us? Reading the stories and books of Don Miguel Ruiz, Carlos Castaneda, or Black Elk can start to open our psychic channels to the Way of Purple. Studying local history and native mythology of our current residency allows us to delve deeper into the purple history of local lands, bringing us further in tune with nature and her wonders. I also like to read about ethnobotany and how indigenous cultures understand plants. Meditation and contemplative moments in nature also helps to connect us with the magical forces around and within us. I enjoy going to a nearby river and playing the Native American flute while drinking in the sublime beauty of the land. Listening to Native American or other indigenous music can help to deepen our connection with this enchanted universe.

My later experiences as a former shamanic practitioner in subarctic Canada ignite a world of stories, reverence, acceptance, and listening. With drums beating with the prana and pace of a heartbeat, I entered into and out of a multitude of worlds through the practice of shamanic voyaging. Of course, I traveled as a guardian spirit—a spirit animal that I never consciously selected, but instead arose through the observational practices of listening to the life force of nature in the shamanic trance. Reflecting the well-known adage that when the student is ready, the teacher appears, the spirit animal was said to embody the characteristics and qualities that the shamanic practitioner needs for the next steps in life. For me, what emerged in my first shamanic voyage was a buffalo (known as tatonka to Sioux people) grazing in the Black Hills of South Dakota. So, with the strength, determination, and boldness of tatonka as my starting point, I entered into hundreds of subsequent 20-minute voyaging sessions in which I would explore the natural terrain of this massive animal in gross, subtle, and causal states. In doing so, new narratives ignited as a reverence for natural environments of place and Great Sprit (or wakantanka) arose. I learned to listen to new voices and to accept the guidance that was offered.

Whether we speak in terms of wakantanka or reverence, the Way of Purple is a much-needed remedy for today’s mechanistic, postindustrial age through reinfusing a sense of magic, wonder, and intimacy with nature and all of life. Profound meaning can be found by listening to trees, rocks, skies and various environments when we tap into this primordial wellspring of spirit. The effects are also very practical as evidenced by my shark story or through the serene surrender of the Hawaiian people to Pele’s wrath. Whether witnessing the apocalyptic power of volcanoes or taking a stroll in the woods, the power of the Way of Purple is always available to us, bringing the world to life and awakening within us the true feeling of being alive!

Unleashing the Power in the Way of Red through Martial Arts and the Dynamic Rhythms of Life

![]()

In today’s world, the word “tribal” is often used as a pejorative to describe regressive societal behavior such as gang violence, racism, ethnocentrism, and polarizing partisan allegiances. Being “tribalistic” implies one is not living up to a modernist sensibility, instead resorting to uncivilized barbary uninformed by any ethical standards—living like baboons, to borrow Henry David Thoreau’s (1910) words. However much our disdain for tribalism today, we are reminded that tribal consciousness has historically been a major operating system for much of the world and still is today. As a universal stage of development through history and a foundational pillar of our psyche, it is important to acknowledge and integrate the best parts of the Way of Red while being hyper vigilant of its negative aspects. In doing so, the pathological manifestations of tribalism can be curtailed, encouraging a healthy development of the Way of Red in all of its forms.

Reflective of the warrior archetype, the leadership gifts of the Way of Red include a raw energy, gumption, and the power of pride, along with an opportunistic orientation in which we “get ‘er done come hell or highwater.” Indeed, the Way of Red consciousness gets our blood boiling, our pupils dilating, our adrenaline pumping. It is the impulse of primal instinct, our reptilian brains firing, our fight or flight or freeze mode activating. While such impulses have been an important aspect of our survival as a species, operating solely from a Way of Red consciousness in a modern and post-modern world is bound to get us in trouble. However, this vital realm of instinct need not get completely left in the dust by civilized progress. Psychologist Sigmund Freud based his entire psychoanalytic theory of pathology on repressed red impulses of sexuality and aggression, showing that a healthy dose of the Way of Red is necessary to maintain the equilibrium of our psychic life—a lesson I learned during the difficulties of my teenager years.

Growing up in the town of Kona, I was the quintessential weak, sickly, feeble child, who was fearful of everything and timid as a mouse. My diffidence was exacerbated by my parents’ emphasis on the traditional Japanese values of humility and self-effacement, further emasculating my development of a healthy male identity. Unable to properly confront the challenges of teenage life, I eventually dropped out of high school, which led to a sort of adolescent spiritual crisis. As a lost teenager enraged at the world, I instinctively gravitated towards gangster rap music and hip-hop cultures, imbibing my mind with the lyrics of Eminem and 50 cent and spending long hours on the basketball court.

As fortune would have it, I eventually came under the tutorship of a man named Carlo, who introduced me to boxing. After enduring some trying times, Carlo developed an interest in mentoring lost young men, such as myself. As I quickly discovered, boxing unearthed the deeply repressed Way of Red consciousness that had been squelched by my family’s strict moral admonitions. Slowly, I developed a newfound sense of confidence, as I was invigorated by this released surge of primordial energy. I started to become comfortable with my inner warrior as I harnessed my rage and resentment into the productive action of physical exercise. I went on long runs in the wee hours of the morning and pummeled the heavy bag into the late hours of the night. I developed a keen sense of focus and an unwavering determination as I fortified my body and galvanized my mind. I felt like I was on the way to becoming something of a Nietzschean Ubermensch (1961) as the unearthed values of pride, ego, and power devoured my old ways of humility and meekness.

As I came to realize, the essence of this tribal redness was embodied in rhythm. There was a natural consonance between boxing, basketball, and rap music, which all heavily relied on a rhythmic pulse. In outgrowing my teenage angst, the spirit of the Way of Red stayed alive within me when I connected with rhythmic flows, whether it be through boxing, martial arts, sports, or music. There is a reason why music from indigenous tribal cultures relies so heavily on drumming and rhythm, especially to induce altered states of consciousness. Tribal music summons our deepest genetic impulses to the surface, reawakening this primal power within us. It is as if all of our ancestral history contains these ancient memories, teleporting us far back into our tribal past.

Unchecked, however, the Way of Red consciousness can all too easily resort to violence and impulsiveness, as acting only from instinct will not end well in modern and post-modern life. We see this problem in some developing countries, living out an eye for an eye philosophy as identity is confined to immediate familial relations. Yet, as social change agent Mahatma Gandhi is said to have remarked, “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind” (Dear, 2016). For the Way of Red, the whole world is not of concern, however. What is of concern is my world, this nation that I am proud of, and will be damn sure to protect, with an unbridled energy, the guts of gumption, and the power of pride. In this Way of Red, it is quite appropriate that the original-essence of the word, pride, points to “congratulating prejudice.” We see this hallmark of the Way of Red not only in martial arts, but also in the rivalry of sports nations that pit one team against another.

Consider the fight songs of high schools and colleges across America. Take, for instance, the fight song of the University of Mississippi affectionately known as Ole Miss: “Forward, Rebels, march to fame, hit that line and win this game, we know that you’ll fight it through, for your colors red and blue. Rah, rah, rah! Rebels you are the Southland’s pride, take that ball and hit your stride, don’t stop till the victory’s won for your Ole Miss. Fight, fight for your Ole Miss!

And from “Future Rebel” the Favorite Cheer! HODDY TODDY ARE YOU READY??? Hell yes, damn right!!! Hoddy toddy gosh almighty who in the hell are we…HEY!!! flim flam, bim bam OLE MISS BY DAMN!!!” (Lyrics on Demand, 2019)

The question in this fighting, “my way or the highway” way of the world is, how can we consciously cultivate the power of the Way of Red without succumbing to its brute force and raw aggression? Martial arts master Bruce Lee offers an insightful answer. Influenced by the philosophies of Krishnamurti, Daoism, and Buddhism, Lee (Little & Lee, 2000) pointed out that fighting only from instinct is animalistic, whereas fighting only from technique is automaton; a true martial artist integrates the two.

For me, this philosophically astute statement captures the wisdom and practicality of martial arts and sports. Martial arts allow us to (re)connect with the Way of Red, harnessing its gifts of energy and invigoration, while scrutinizing it to discipline and order. Essentially, the raw impulses of the Way of Red are sublimated, or transmuted, to a higher art form, transforming our consciousness in the process and infusing our instincts with an aesthetic grace. The shadow of the Way of Red lies in losing control and getting pulled down by its gravitational force of aggression, but practicing martial arts or sports allow us to master control over it. This polarity of control/losing control marks a central tension within the Way of Red consciousness.

There is something both therapeutic and empowering about connecting with the force of the Way of Red. In the short time that I taught boxing, I witnessed firsthand the healing power from reconnecting with our instincts in a healthy way, and to safely vent repressed anger and aggression through a disciplined form. One student wanted to learn boxing to take control of her feelings of blind rage that she would occasionally fly into. Boxing allowed her to bring awareness to her anger through movement, which was then anchored into her body through the rhythm of repetitive practice. By creating a container of discipline and building on it through practice, we infuse our instincts with the light of higher awareness, refining and maturing the expression of these once blind impulses.

When I need a healthy dose of the Way of Red energy, I go to the gym, hit the heavy bag, practice basketball, and listen to my homemade philosophical rap music. For me, it is important to regularly express the Way of Red consciousness and to be proactive in cultivating it, so it doesn’t erupt and seize me at an inopportune moment. I have found it healthy to regularly be in touch with these primordial tribal rhythms, infusing my life with a daily dose of energy, vigor, and willpower. When unharnessed, the Way of Red can be the scariest level on Beck and Cowan’s (1996) spiral, but when cultivated, we can only awe at the marvelous power that radiates from this stage of our primordial human history.

The Way of Blue through Tradition, Character, and Devotion in Buddhism and Japanese Arts

![]()

Growing up in a Buddhist temple in Hawaii gave me a unique taste of culture, community, and tradition. This upbringing demonstrated the Believer archetype of the Way of Blue. I also learned the leadership gifts of discipline, order, consistency, and structure. In Hawaii, Buddhism and Japanese cultures are inextricably linked, as Buddhist temples act as community hubs for Japanese cultural preservation. As a child, I disliked growing up in such a public area, as I was assigned to answer door bells and phone calls and forced to lend a hand at temple events, often begrudgingly. Unlike my sister, who enthusiastically embraced her Japanese cultural identity, I sought to distance myself from any traces of Japaneseness, as traditional Japanese values clashed with the “American” values of my white schoolmates. But now that I can make object into what was earlier subject (Kegan, 1998), I can appreciate the lessons and values that were instilled in me from my parents and community as these foundational experiences allowed me to cultivate a healthy identity as an adult.

Buddhism is a religion that offers something to everyone. My Buddhist temple, Daifukuji, spanned the whole spectrum of human development, including old coffee farmers who believed in ghosts and fairy tales, to Japanese traditionalists who served with tireless devotion, to retired academics from postmodern college environments. Somehow everyone got along, and all found their respective places under the great temple roofs of Daifukuji. The old ladies hustled and bustled in the kitchen, the men bonded over beer and power tools, and the intellectuals discussed the nuances of Buddhist scripture and philosophy. Such a diverse community was truly a remarkable sight and at its core is held together by the Way of Blue consciousness.

While every niche contributes something beautiful, I have come to respect the old time Japanese traditionalists the most. These old Japanese folks, many of whom are women (they outlived their husbands), serve the temple with the utmost devotion, working long hours on end, often from the wee hours of the morning. They seize the day by spearheading events and take charge with their commanding leadership presence that no one dare question. Even more remarkable, many of them are in their 90’s, but looked and act as if they are in their 70’s! Their unwavering commitment and no nonsense attitude was a humbling sight to behold and instantly commands one’s respect.

Many of these industrious old timers don’t practice Buddhism as we understand it in the west. They don’t meditate, read philosophical sutras, or contemplate the impermanence of existence. But they are devoted to serving the temple because their families and parents had done so in the past. Core to these traditional values is looking to the past to guide the future. Keeping the tradition of service alive, they happily serve in whatever way possible, whether it be setting up for large public events, cooking up a storm in the kitchen, or assisting with weekly cleaning activities (called Samu). They comprise the raw manpower of the temple, from setting up benches to chain-sawing down trees. Without them, not only would things not get done, but the spirit of service would be lost, which would quash the morale of the entire community.

This devotion, consistency, and alacrity is something truly captured by old timer traditionalists inherent in the Way of Blue. Sadly, the Buddhist laws of impermanence take their due as more and more of these old timers are being lost to father time. While Daifukuji has attracted an increasing number of retired intellectuals, who do give back and volunteer in remarkable ways, they lack the raw vigor and pep in their step to adequately replace the indefatigable enthusiasm of the traditionalists. Many of these new volunteers, who are deeply steeped in the Buddhist practice of mindfulness, approach service as a way to cultivate this serene state of mind. While mindfulness is a great practice, it simply cannot replace the gung ho attitude of the old timers, whose infectious attitude galvanizes the whole community into action.

Other notable qualities of the old timers were their humility, selflessness, and grit. They never once complained, wined, or avoided a task. Mired in health problems, many of them suffered from chronic illnesses, pain, and discomfort, but never mentioned it. They had no desire to inform others of their pain and discomfort, as they never sought sympathy from others. Some would be back to running around in the kitchen immediately after a major surgery! Their only intention was to serve wholeheartedly and to always maintain a positive attitude in any circumstance. Inured by life’s hardships, their stolid demeanors and stoic temperaments were both humbling and inspiring, a true testament to their character.

The slow decrease in old timers brings up further questions about how to recruit more people to Daifukuji, so it doesn’t close down like other Buddhist temples in Hawaii. The precipitous decline of the Buddhist temples in Hawaii was featured in the documentary Aloha Buddha revealing how the loss of old timers contributed to the ineluctable disappearance of temples in Hawaii. For many of these temples, their role in the community was not only to provide Buddhist teachings but to serve as centers of Japanese cultural preservation. Offering traditional Japanese arts, such as Taiko drumming, Judo, or calligraphy, is integral to preserving temple life, as both the young and old can unite around the commonality of culture and tradition.

The importance of tradition was highlighted by the English founder of conservatism, Edmund Burke (O’Keeffe, 2009). Burke championed the Way of Blue consciousness, revealing how modern commercial life and radical societal changes disrupt the moral fabric of culture and community, which in turn lead to an erosion of ethical values and virtues. Burke illumined how we need the anchors of tradition, culture, and community to ground ourselves in the chaos of a changing world, as rapid changes can unintentionally undermine cultural norms that provide stability and social cohesion. While Burke expounded his message in 18th century, his insights into the importance of the Way of Blue are still relevant today as he forces us to appreciate existing institutions and norms, while admonishing the drawbacks of radical change in the relative terrain of consciousness.

Traditional Japanese arts, such as Taiko drumming, are congenial with Burke’s concerns. I had the honor of being enrolled in Taiko drumming as a child. Distinct from western drumming, Taiko emphasized more than technical skill and percussive virtuosity. It was a way of developing the whole individual, making it a combination of martial arts, music, and spiritual practice. The traditional Japanese values of honor, respect for teachers, discipline, and hard work were instilled in the minds of youth, proving to be more than a mere after school activity. It was a way to develop the intelligences of body, mind, and spirit, all while banging away on a giant cowhide drum. For some, it was a way to hang out with friends and release stress, but for many it became a way of life and a path of cultivating virtue and character.

It is no coincidence that traditional arts such as taiko drumming tend to attract many wonderful youth from the community. Through disciplines such as Taiko, these kids were all endowed with the values of service and perseverance from a young age. As Taiko took place at Daifukuji, students were expected to give back to the temple and worked side by side with old timers at major events. If you were going to participate as a drummer, you were also seen as a part of the community. This expectation to give back to community inspired a character building that translated well into their personal lives, leading to success in school and sport, as many were offered scholarships to prestigious universities such as Stanford and Harvard. As journalist David Brooks insightfully portrays in his book The Road to Character (2015), we are wise to develop systems that build character in education and community.

However, without access to such traditions inherent in the Way of Blue, it can be difficult to learn character building values in a world in which they are not explicitly affirmed. Our postmodern society, with its emphasis on sensitivity, feelings, and equality, has eschewed the stoic emphasis on becoming inured to suffering and discomfort, seeing it as an anachronistic form of abuse or traumatization. This is why it is paramount for temples such as Daifukuji to carry on these traditional cultural arts, as they not only preserve the wisdom and virtue of Japanese traditions, but also encourage these values to live on in the minds and hearts of youngsters. Endowing our young people with these forgotten character virtues gives them the moxie to tackle the emerging problems of our future and to lead personal lives of greater flourishing. The spirit of community, the depth of character, and the devotion to serve are all embodied in the wisdom of tradition, which I hope is never forgotten.

The Way of Orange through Critical Thinking, Reason, and the Freedom to Chose

![]()

I’ll never forget my first day at my first job. I had recently graduated from college and began my search for the dreaded first gig that bedevils many recent graduates. I scoured the local newspapers for job postings and found one that said “Living History Museum Interpreter.” I threw together a resume and sent in an application. After a nerve-wracking interview and a couple of sleepless nights, I was offered the position. Little did I know this job would be my initiation into the Way of Orange modernity and my right of passage into the real, adult world.

The college that I attended was no ordinary college. This was not a college that taught me to strategize, to take calculated risks, and to be efficient in the pursuit of achievement and accomplishment. Rather, this was a “spiritual” college that valorized intuition over reason, feelings over facts, and the Guru’s word over evidence (and everything else, for that matter). As portrayed in Esbjorn-Hargens and Gunnlaugson’s Integral Education (2010), conventional education emphasizes the exterior at the expense of the interior, while alternative education emphasizes the interior at the expense of the exterior. This college certainly exemplified alternative education. To demonstrate, my math classes consisted of sacred geometry, my science classes of energy medicine, and my classes on meditation and higher consciousness were… well just that. It was an interesting experience to say the least, but something was painfully absent; anything hailing from the enlightenment, such as reason, evidence, logic, and critical thinking were all denounced as materialistic trappings that originated from “lower levels of consciousness.” While I was a wiz in East Indian medicine and ancient Hindu astrology, I really didn’t know much of anything else.

The job I had accepted was to be a tour guide at a living history museum, which portrayed the daily lives of 1920’s Japanese coffee farmers in Hawaii. I, the docent, dressed up as a coffee farmer (I looked like Pokemon’s Ash Ketchum sporting a Mexican sombrero) and set out to educate visitors on topics ranging from Japanese internment in WW2 to the political and economic history of Hawaii. As you can imagine, I fell flat on my face. My new age bubble was virulently burst on my first tour as I realized I knew nothing of the real world or how it worked. Worse still, nobody gave a damn about Vata imbalance, kundalini, or if your venus was retrograde in scorpio. I had some major catching up to do and set out to learn everything my education didn’t teach me.

First things first: I had to tear down the new age malarkey I was inculcated with at my college. But what should it be replaced with? What could supplant meditative intuitionism, the primacy of feelings, and the admonishments of an all-knowing Guru? The answer was loud and clear: Reason. Somehow in my life, I had glossed over this crucial faculty that serves as the bedrock of our modern civilization. I began devouring the books and lectures of the new atheists, such as Sam Harris, Bill Maher, and Christopher Hitchens. I learned to spot logical fallacies and spurious arguments and used these critical thinking tools to eviscerate my magical beliefs. I took the rational hammer to all things atavistic, antiquated, and anachronistic, and launched an excoriating invective against the younger, naive me. To paraphrase the enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant, I was awoken from my dogmatic slumber (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2018). With the critical faculties of my mind awakened, my confidence soared, as the mysterious world around me began piecing itself together.

The rational powers of my mind reached an apex when I began to study philosophy. Through philosophy, I learned to deeply question my assumptions, beliefs, and unconscious presuppositions that once served as the bedrock of my worldview. I subjected my intuitive hunches and moral impulses to critical inquiry and observed if any of them made rational sense, immediately discarding them if they didn’t. I bored into the deepest recesses of my psyche to illuminate my most deeply cherished opinions and ideologies and scrutinized these implicit axioms with the light of reason. Spiritual meditations taught me how not to think, but I never learned how to think. In doing so (or not doing so), I never questioned the context or the paradigm in which my thinking took place. Philosophy liberated me from such limiting frameworks and irrational beliefs. To paraphrase empiricist philosopher David Hume (1748), I learned to commit it to the flames for it was nothing but sophistry and illusion.

Of course, my growth as an individual didn’t stop there. Perhaps the most transformative aspect of my journey into philosophy was my newfound confidence in communicating and perhaps even disagreeing with others. Throughout my life, I hated disagreements or potential conflicts and did everything in my power to avoid them. But armed with the philosophical toolkit, I learned to parlay surface disagreements into deeper philosophical explorations and in doing so no longer feared potential conflicts. When I would bring a conversation down beneath the turbulent waves of the ocean surface to the calm depths below, people would remain cool and collected. Everyone knows not to talk about religion or politics, but no one ever says not to talk philosophy! This ability to ask questions and listen deeply was very helpful at my job and has served me well in life. Thinking and conversing dominates our lives; learning to do so perspicuously never hurts anyone.

Another liberating feature of the Way of Orange is increased freedom. When pushed too far, this freedom can amount in alienation and anomie, but a healthy dose of freedom is necessary to form a healthy, adult self. When modernity was in full swing during the scientific and industrial revolutions, many astute commentators chronicled the groundbreaking transition from traditional to modern societies. One such observer was a social critic named Georg Simmel (Wolff, 1950). Simmel observed that unlike traditional, medieval guild-based societies where everyone in your town knew everything about you, modernity allowed us to segment our identities and explore a particular interest in civil society without bringing all of our past baggage with us. I experienced this liberating freedom of identity when I moved to Portland, Oregon. Unlike the much smaller town of my upbringing in Hawaii, no one knew who I was or anything about me. I was completely free to (re)create myself at will, join whatever group I pleased, and got off to a fresh start in life. I was completely anonymous, but totally free.

This theme of expanded freedom dovetails with the modern rise of ethical neutrality. In the world of premodern antiquity, ideas of virtue and goodness dominated discussions of ethics and morality. With the dawn of modernity, old and potentially dogmatic notions of human goodness shifted towards abstract and neutral concepts of morality, which resulted in the separation between the “right” and the “good.” In premodernity, if something wasn’t considered “good,” it wasn’t “right.” Innocuous activities such as use of intoxicants, money lending, or certain sexual activities were outlawed, usually punishable by death (homosexuality is still outlawed in several Muslim countries with the punishment usually being death in brutal fashion). The Way of Orange freed us from dogmatic and oppressive notions of goodness, aptly expressed by philosopher John Stuart Mill’s Harm Principle: If your actions don’t harm anyone else, they’re perfectly fine (The Ethics Center, 2019).

A recent incident captures the value of non-judgmental, neutral thinking. Several months ago, my landlord went into my garden and prematurely harvested all of my potatoes without my permission. On top of that, he was too afraid to confront my girlfriend and me about the incident and one morning hid from her behind his truck to avoid a confrontation. Outraged by such negligence and cowardice, I fulminated over his carelessness and complete lack of respect and lambasted his “low character” and pusillanimous spinelessness. But when venting to others about the incident, they interpreted it differently than I did: He simply lacked the “social skills” needed for an adult conversation or perhaps even suffered from some sort of anxiety disorder, causing him to manifest such “cowardice.” I was still angry, but these neutral perspectives helped me to see the situation differently, which helped to soften my vituperative value judgements.

This kind of moral neutrality makes society as a whole less judgmental and grants people expanded freedom to pursue their own (harmless) interests. If other people don’t conform to our limited and skewed notions of “the good,” who are we to judge? “To each his own” says the Way of Orange; we must find our own individual path to virtue and goodness. This neutrality also has major implications in the professional sphere and gave rise to modern notions of what it means to be a consummate professional. For example, it doesn’t help for psychologists to tell their clients to simply “be a better person” or “toughen up” if they suffer from anxiety and depression. If a conflict erupts in the workplace, upper management or HR may be deployed to adjudicate it through diplomatic techniques of “conflict management.” The professional manager and therapist must refrain their value judgements and resort to proven techniques to help one through their personal problems. What was once personal is now “just business,” as such detachment promotes objectivity and neutrality, while maintaining healthy professional boundaries.

Learning to become a professional has been the crux of my journey into adulthood. To use the language of cultural anthropologist Florence Kluckhohn (1953), my experiences with the being cultures of Hawaii had shifted to also embrace the more doing-oriented cultures of the Mainland. From relying on family background, social relationships, and the hang-loose nature of “Hawaii time,” I learned to show up on time, budget myself, and shove aside my own personal needs in order to best serve customers. I learned to “dress for success,” sell, and serve in very different ways than I had previously known. Segmenting my personal and professional personas was both liberating and empowering to me, as no matter how hot, tired, or shitty I felt, the customer always came first. Professional duty superseded my childish needs of self-concern. Being endowed with responsibilities grounded me and fostered a sense of pride in my work, which stabilized the emergence of my adult identity. Professionalism was my true initiation into the adult world, as it could be summed up by the phrase it’s not about me.

This confluency between freedom, neutrality, and professionalism segue into another core virtue of the Way of Orange modernity: The rise of consensualism, of “win win” contracts between agents seeking to promote their own self-interests. Political social contracts between self-interested citizens, free market exchanges between buyers and sellers, and free associations in civil society all arose as a product of the Way of Orange. Consent gives us both the freedom and choice to do what we please: We can choose who to vote for, what to eat or where to work, and who to associate with. We learn how to negotiate “win win” situations and learn to think strategically towards such ends. As classical economist Adam Smith (1789) observed such strategic and organized thinking spills over into other avenues of life, helping us to become more efficient in our personal and professional pursuits.

The Way of Orange marked my baptism into the adult world. I have become more mature and able to see things from more perspectives, as I can now dissect topics from multiple angles. I have learned to question the very foundation of my worldview, which provided me the tools to properly frame an issue for contemplation or conversation. I have found a newfound freedom in myself, as I no longer need to conform to rigid standards of goodness, making me more free, more tolerant, and less judgmental. In articulating what the Enlightenment is, philosopher Immanuel Kant famously wrote “… Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity” (32). Like the unstoppable progress of Enlightenment modernity, the Way of Orange ushered in a new era of truth in my life, where my self-incurred immaturity of magical thinking, irrational delusions, and antiquated values were confined to the dustbin of history.

The Value of Lived Experience, Contexts, and Sensitivity in the Way of Green

![]()

We have all received some form of discrimination in our lives, whether it be racism, sexism, classism, or any other “ism” that suppressed our identities and made us feel less than we are – what American children’s performer Mr. Rogers considered an ultimate form of evil (Neville, 2018). My entrance into this world of marginalization started early in my childhood. I remember my first days of kindergarten, waddling into the world as an innocent, bright eyed five-year-old in awe of everything around me. Sadly, my state of innocence was short lived as I was shocked out of my wonder with disparaging remarks about my race, ethnicity, and religion. “God is stronger than Buddha” one teacher told me. “What is wrong with your eyes? How is it possible for you to see?” asked a curious student. “What does ching-chong-ching-chong mean?” Such remarks quashed the development of my self-identity and made me to feel ashamed for who I was, which resulted in a pathological lack of self-esteem that has come to characterize much of my childhood.

Unfortunately, this experience is all too common, and has triggered a massive push for a more equal, inclusive, and non-judgmental society. Such a wave is captured by the values of the Way of Green, in which sensitivity to the feelings of others and awareness of social power dynamics are valorized. The Way of Green consciousness recognizes the context of our statements, actions, and behaviors, and understands the need to see things from different perspectives so that no voice goes unheard or unacknowledged. Egalitarianism and inclusivity, especially of diverse ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds, becomes paramount in the Way of Green.

Of particular importance in the Way of Green is the value of lived experience. Every human being has a unique lived experience, but the Way of Green especially focuses on those who have experienced racism, oppression, bigotry, and general mistreatment from society. The Way of Green highlights that we all don’t experience the same “privilege” and as such, it is unfair to lump all people into the same category or hold them to the same standards. Many critics of the Way Green point out that we are all the same as human beings and should therefore highlight similarities between peoples instead of differences, and even advocate returning to a colorblind society. While some of these criticisms are valid, critics often misunderstand that while we all contain the same intrinsic value as being a part of the greater human family, we all have different lived experiences that vary according to our standings in society. The Way of Green ensures that such overarching narratives do not steamroll the particular perspectives and experiences of others and seeks to include them all in an egalitarian embrace.

The unique value of lived experience can also enrich the collective wisdom of a group or organization and has many implications for (dis)solving societal issues. A Way of Green defense of affirmative action could proceed as such: If there was a sociology class that sought to improve the conditions of black, inner city ghettos, would you rather have a class where everyone is white and from a privileged, affluent background? Or would you want to include at least a few black kids who came from such disenfranchised neighborhoods, who could relate to people from those communities and understand their suffering first hand, even if their SAT scores weren’t as high as those of the white kids? The Way of Green’s valorization of lived experience can act as a necessary counterweight to the cold metrics of “objective” merit and understands that such perspectives are necessary for rounding out the collective wisdom of a group.

But the Way of Green doesn’t stop at the inner level of lived experiences. The Way of Green also understands the value of (re)presenting people’s exterior characteristics, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity. My teenage years were marked by perpetually seeking for an Asian American role model. I loved sports: Basketball, boxing, football. But, of course, all of the athletes were black or white. I then turned my attention to intellectual pursuits. Surely I would find some Asian people here, but again most major intellectuals were white or Jewish. How about pop culture, such as musicians or actors? These fields are loaded with people of all colors and backgrounds, except Asians. I felt disheartened that no one “successful” looked like me and jumped to the conclusion that Asian Americans simply can’t be cool, popular, or valued by the community. The Way of Green deeply empathizes with my teenage despondency, and heavily pushes diversity in representation so that others of a similar group identity believe they have a chance.

I tried to convey the importance of the Way of Green in a recent conversation with a friend. I shared how I often felt uncomfortable in certain environments, usually due to being the only minority present. My friend, who grew up in the predominantly white town of Beaverton, Oregon, was quite astonished. He replied that not only has he never felt uncomfortable about his racial identity; he didn’t even know it was possible to feel that way! For the Way of Green, such ignorance of others’ experiences is called “white privilege.”

For those who are skeptical of such a term, consider the following example. Last year, a young woman in Portland, Oregon was accidently killed by a reckless driver who happened to be an exchange student from Saudi Arabia. The backlash of racist remarks against the driver was astounding, as the poor fellow was lambasted with a deluge of vituperative pejoratives spewed from Youtube, news commentary, and from Portland at large. Would this young man have received the same amount of racist hate had he been white? Probably not. This lack of societal privilege is analogous to the Buddha’s notion of the “second arrow.” The first arrow, or the raw pain of an experience, hurts enough. The second arrow—our barrage of judgmental commentary and self-criticism—amplifies it tenfold. In the case of the driver, it was bad enough just to deal with the tragedy at hand (i.e. 1st arrow). The second arrow, in this case fired by society, only adds to the pain and stress of the first arrow. It’s painful enough to be attacked for who you are (e.g. your character, personal behavior, etc.), but it’s another issue to be attacked for what you are (e.g. your race, ethnicity, gender, etc.). The Way of Green recognizes that minorities often suffer from both attacks and does everything in its power to close this gap.

The Way of Green’s understanding of context and lived experiences gives it sensitivity to statements or behaviors that are innocuous in one context but harmful in another. I was traveling through a small town in rural Washington and stopped to order coffee. For some reason, my order was delayed or forgotten and people behind me were receiving their orders first. Due to being the only minority present, I had a moment of feeling highly self-conscious and uncomfortable about my racial identity: “Is the barista racist? Should I say something?” Of course, it was most likely just a mistake, but in that particular context, something benign could be translated as something malicious.

A few more examples help to illustrate this point. After a mistake made by a black basketball player, the radio announcer said “he must be out of his cotton-picking mind!” That phrase may be fine to use if the player was any other race than black, but due to the particular history of slavery and oppression of black people in the USA, was definitely insensitive. Another time, I was at a meditation retreat which took place during Trump’s infamous Muslim travel ban, and one attendee said to the teacher that “everyone is afraid and losing their minds…over nothing!” Of course, this man was white and didn’t consider the perspectives of thousands of terrified Muslim Americans who were unable to go home or connect with their families. The Way of Green takes issue with such insensitivity and ignorance and seeks to make people aware of these underlying power disparities.

But the Way of Green’s sensitivity extends far beyond race relations (and class and gender and sexual orientation) and intersubjective power dynamics. It also includes a sensitivity to the exquisite realm of life itself, to the living biosphere and all of its inhabitants. The environmental movement was birthed by the Way of Green, which sought to bestow ethical rights to the delicate ecosystem that nurtures and sustains us daily. As a child, I was appalled when I saw other boys torturing a grasshopper, treating it as if it was an object and not a living creature. For the Way of Green, such moral concern encompasses the entire globe, and treasures all life here on planet earth. The Way of Green sees Gaia as a living, breathing organism, and not an inanimate pile of resources for human appropriation. In this respect, the Way of Green shares a strong consonance with the Way of Purple, as the natural world becomes re-enchanted and valued for what and who it is.

This is the brilliance of the Way of Green. It questions the very context that once defined our existence and reveals how those boundaries that delimit our understanding can be constraining. When we question the boundaries of a paradigm, we can come to enlightening insights: We see it’s ridiculous to believe in infinite economic growth on a finite planet, which birthed the sustainability movement. We become aware that our values that we once deemed universal and ubiquitous are actually just the internalized values of the particular culture we are embedded in, birthing the multicultural movement. We see how labels and traditional roles can be repressive to our true selves, birthing identity liberation movements. Such metacontexual awareness loosens the rigidity of our interpretations and identities and opens the door to more creative notions of self and truth. To paraphrase Ken Wilber (2000) where we build the boundary lines is where battles occur.

My view of the world has been greatly enhanced by the Way of Green. I have developed a more sophisticated sensitivity and concern for peoples of various backgrounds, understood the wisdom and beauty of including and honoring the perspectives of others, and learned to respect the profundity of everyone’s lived experience. I have learned to appreciate the exquisiteness of the natural world, and reclaimed a sense of wonder for the sacred web of life we are all ensconced in. While the Way of Green has many flaws and shortcomings, it has no doubt contributed to a more humane, just, and compassionate world, where people of all races, colors, and creeds can begin coexisting in peace and harmony. In summary, the Way of Green is the ultimate expression of the “grass roots,” and like the roots of a great tree, provides the path for which our authenticity, sensitivity, kindness, and compassion can reach all the way down.

Second-Tier Way of Leadership

We have toured the leadership gifts of the Way of Purple, the Way of Red, the Way of Blue, the Way of Orange, and the Way of Green—that is, first-tier consciousness. Across the diversities of this first-tier way of leadership is one commonality: Each way views its way as “the way,” while other ways are viewed as inferior. While some ways may get along better with others, this compatibility still holds an underlying tension. This tension significantly morphs in second-tier consciousness. Not only does this second-tier way of leadership honor and embrace the leadership gifts of first-tier consciousness, but when wholly practiced also represents a monumental shift in beginning with the whole, then extending to part, rather than part to whole. The impacts of this whole-to-part approach are profound in both individual and collective terms.

The developmental trajectory of individuals reflects the developmental trajectory of communities. This developmental trajectory—from premodern, to modern, to post-modern, to this second-tier, integral consciousness—encompasses a myriad of perspectives. A hallmark of this developmental trajectory is the increased capacity for perspective-taking. Early in the pre-modern ways (Way of Purple, Way of Red), we take a first-person perspective, which later grows into a second-person perspective of self and other in the Way of Blue. In the modern Way of Orange, we also consider external environmental factors through a third-person perspective. Then, in the post-modern Way of Green, our newborn awareness of contexts (i.e. internal environments) births a fourth-person perspective. Alas, with the second-tier way of leadership, we begin to hold multiple contexts simultaneously and adjudicate systems upon systems through a fifth-person perspective. In doing so, we begin to hold the various leadership gifts sparked in our evolution through first-tier consciousness.

Generally speaking, as consciousness matures so too does compassion. As perspective-taking increases so too does empathy-giving—and the more perspectives that are included in anything, the more encompassing and sustainable its impact. Thus, compassion and empathy are a consequence of the perspective-taking that travels with the maturation of consciousness. In gleaning into finer and finer parts within an ever-enlarging whole, the maturation of consciousness—not in a rigid, fixed manner, but in a fluid, pervasive way that allows us to become more and more of who we already are—offers the spaciousness and stillness to more fully and freely offer our gifts in and to the world.

As our potentialities and actualities come into closer coherence, a myriad of life-affirming qualities awaken. A particularly poignant potentiality is awakening the capacities within ourselves to take multiple perspectives, to more deeply empathize, and to make meaning in ways that bring our inner and outer selves into closer congruence. To be clear, individuals and communities mature in a stage-based model, with each later stage including and transcending the earlier stage, evolving through the various ways of the world in the first-tier way of leadership—from the Way of Purple, to the Way of Red, to the Way of Blue, to the Way of Orange, to the Way of Green. The maturation of these color-coded ways of the world reflects increasing wholeness, consciousness, and compassion. The second-tier way of leadership is represented by the Way of Yellow.

The Way of Yellow through Inclusiveness, Wholeness, and Robust Practicality

![]()

Ever since I was a child, I held a natural inclination to integrate disparate or dualistic perspectives into a coherent whole. Ken Wilber’s well-known adage that everyone holds a piece of the truth always rang true with me and has subtly shaped the basis of my engagement with people and ideas. I always strove to understand the big picture and tried to appreciate different perspectives – even those that were alien to me. I grew up in the world of Zen Buddhism, but was fascinated by other wisdom traditions, such as Christianity or Hinduism, and sought to learn from these traditions to supplement my Buddhist cosmology. I understood the importance of allopathic medicine but was quickly turned onto alternative practices such as acupuncture and herbal medicine and found that the two dovetailed nicely. When first registering to vote, I asked my dad if I should be a Democrat or Republican, which he replied: “Democrat. Republicans are racist, corrupt, old white men who are driven only by greed.” Somehow, this binary, black and white dichotomy didn’t feel right to me, which launched my journey of truth seeking and conciliation in the political realm.

I quickly discovered that most others didn’t share this similar impulse: People seemed happy to settle into a fragmented reality of black and white, good vs. evil, or materialist vs. spiritual paradigms, fully condemning the opposite side of their position. Such a polarizing dichotomy seemed not only hyperbolic and inaccurate, but also impractical as all of the knowledge, wisdom, and insight from the “other side” was shut off from exploration. This bifurcation of the world confused me, and fueled my question “Who was right?” “Are all of these other people wrong?” “Do their perspectives, values, or moral propositions hold no weight in reality?” As John Stuart Mill pointed out in On Liberty (1869), he who knows only his side of the case knows little of that.

Luckily, my confusion was short lived, as I encountered the works of Integral theory by Ken Wilber at the age of 17. At the time, I had just landed a job on a dragon fruit farm on the Big Island and was thrilled to use my hard-earned cash on many of Wilber’s books. Box after box arrived at my doorstep, and I delighted in indulging in the world of Integral theory after an arduous day of work in the sun. I was thrilled to find that my impulses towards wholeness and integration were not only legitimate but lauded as an important and emerging stage of human development called “Yellow,” “Second-Tier Consciousness,” “Teal,” or “Integral.” Of course, I wasn’t hovering at a lofty Integral altitude, but I was now more aware that these lifelong impulses towards integration did indeed stem from a deeper place. Through continual reading, reflecting, and meditating, my inner and outer worlds began to synthesize, even as I continued to struggle through my teenage angst.

Unlike the previous stages, the Way of Yellow sees the validity and coherence of each lens of life, way of the world, or stage of development, and understands their unique contribution to the ladder of human evolution. Beneath our surface disagreements, opinions, and specific views lies an underlying bedrock of values that many can agree with. KKK and Neo-Nazi members may hold repugnant views about race and society, but beneath the “unhealthy” manifestation of their worldviews lies the more virtuous concern for family, country, justice, etc. even though the specific manifestations of these views can be odious indeed. The Way of Yellow sees that everyone is trying their best with where they are, and when you dig deeply enough, common ground can be found. The Way of Yellow is thus the most inclusive, compassionate, and wise stage of human development and seeks to provide a path out of our current miasma of conflict and polarization.

The power of the Way of Yellow is that it sees the value and integrity in every domain of life, whether it be art, science, spirituality, or religion. Materialistic scientists may lampoon spiritual or interior experiences; atheists may inveigh against religion and vouch for its complete removal from universities (or from the planet), and the political left may hate the right or vice versa. The Way of Yellow seeks to incorporate the healthy truths of all of these different dimensions, while militating against the unhealthy or “regressive” aspects. Thus, the Way of Yellow doesn’t blindly include everything in the name of “inclusion,” which differentiates it from the Way of Green. Rather, the inclusiveness of the Way of Yellow is incredibly discerning. The wisdom of the Way of Yellow lies in its understanding of value hierarchies (or holarchies) and doesn’t hesitate to exclude certain views that are detrimental to the integrity of the whole.

The real value of the Way of Yellow lies in its immense and robust practicality. Many books written from a first-tier consciousness contain the pretext that if only everyone agreed with the author’s worldview, then the world would be a better place. If only everyone had conservative values, or cared about the environment, or realized they are spiritual beings one with the universe, the world would magically transform. The Way of Yellow sees this isn’t the case, as everyone exhibits a different worldview at a different stage of development; it is thus unreasonable for everyone to conform to just one way of the world. Therefore, solutions from the second-tier way of leadership can be more comprehensive, robustly practical, and all encompassing, as everyone from every stage can be mobilized towards a solution.

In Buddhism, the spontaneous wisdom used when appropriately engaging with others is called Upaya, which often translates as “skillful means.” In Integral terms, this is called Flexflow, as one can freely flow between different worldviews, while honoring, valuing, and embodying each one. Sometimes called codeswitching, the Way of Yellow has access to every stage of the spiral and can access each one (internally or externally) to call upon its particular gifts and insights as needed. This obviously has tremendous leadership value, as all can feel included in the magnificent embrace of the Way of Yellow.

Integrative in nature, the Way of Yellow constructs a generative container to hold and include the leadership gifts developed through first-tier consciousness. When appropriate, these leadership gifts are drawn-upon in a way that is both discerning and robustly practical. Unlike the first-tier way of leadership, when fully and freely alive this second-tier way of leadership radically includes the stories, reverence, acceptance, and listening of the Way of Purple; the energy, gumption, power of pride, and opportunistic orientation of the Way of Red; the discipline, order, consistency, and structure of the Way of Blue; the reason, strategic, efficient, and calculating ways of the Way of Orange, along with the context, sensitivity, and value of lived experience of the Way of Green. In the Way of Yellow, practitioners embrace these gifts to often craft a blueprint for all of life, including ourselves, cultures, societies, and nature. More than the translative practices of the first-tier way of leadership, the Way of Yellow deeply emphasizes the transformative possibilities in a value-generating “win-win-win” nature.

Moreover, in the Way of Yellow, I experience the reality that people, like transformative practices, are anchored in the reverence of place—a reality that is often lost in the maturation process from non-differentiated oceanic consciousness (Way of Purple), through identification as the false self that permeates through the Way of Red, the Way of Blue, and the Way of Orange, through the search for the authentic self and true community in the Way of Green. In this way, the Way of Yellow is a transformative homecoming into the deepest, highest most generative self—that is, the sacred place presenced through organizational developmentalist Otto Scharmer’s (2016) Theory U process. In awakening to this prevailing blindspot of leadership, the directionality of life possibilities shifts as the dharmic dance of responsibility (known as kuleana in Hawaiian) calls itself to the forefront of life.

In this transformative homecoming, the Way of Yellow listens and accepts place and people, along with possibilities and purpose in a way that is both highly similar and deeply dissimilar to the reverence of the Way of Purple. In growing from the gross discrimination of premodernity, to the subtle distinction of modernity and postmodernity, to the causal discernment of second-tier consciousness, the Way of Yellow practitioner tends to live through the sufficiency-based starting point of what psychologist Abraham Maslow (1954) called being-needs. Whereas the first-tier way of leadership largely operates through deficiency-needs and seeks to find something “out-there” (e.g. information, knowledge, or achievement), the second-tier way of leadership tends to orient from the enduring wisdom of the self “in-here” and works into the world in a highly generative direction. No longer is surviving or striving of primary concern. Rather, this survive-drive and strive-drive significantly evolves into a thrive-drive and ultimately a live-drive in which the deficiency-based drive-for-life morphs into a sufficiency-based orientation-for-life. In the boldness of this Being and Becoming Orienting Life Direction (BOLD), the service of the deepest, highest most generative self is offered in and to the world. In articulating the essence of integral service, wisdom scholar Roger Walsh (2014) proclaims “we go into ourselves to go more effectively out into the world, and we go out into the world in order to go deeper into ourselves. And we keep repeating this cycle until we realize that we and the world are one” (141).

Personally, I learned about these integrative Way of Yellow values the hard way in my time as a school teacher. While I was seeking to cultivate a Way of Yellow consciousness, I had yet to apply it to the realm of education, which left me with quite a slew of challenges as a teacher. Some children needed firm Way of Blue discipline and a father-like authority to look up to; others needed the tender touch of Way of Green sensitivity. Others still needed to be pushed to being successful in a competitive, Way of Orange manner. Unfortunately, it was only in retrospect that I saw my approach was misguided. I was only operating from a nice, sensitive, Way of Green consciousness, and was thus hamstrung in my ability to meet students where they were at. The second-tier way of leadership doesn’t manifest instantly; it takes time to cultivate the wisdom and skill to practically apply.

In growing from the seeker archetype of the Way of Green to the practitioner orientation in the Way of Yellow, we become more and more of who we already are in a uniquely-connective way. As Ken Wilber states in A Theory of Everything (112),

I am often asked, why even attempt an integration of the various worldviews? Isn’t it enough to simply celebrate the rich diversity of various views and not try to integrate them? Well, recognizing diversity is certainly a noble endeavor, and I heartily support that pluralism. But, if we remain merely at the stage of celebrating diversity, we ultimately are promoting fragmentation, alienation, separation, and despair… It is not enough to recognize the many ways in which we are different; we need to go further and start recognizing the many ways we are also similar. Otherwise we simply contribute to heapism, not wholism. Building on the rich diversity offered by pluralistic relativism, we need to take the next step and weave those many strands into a holonic spiral of unifying connections, an interwoven Kosmos of mutual intermeshing.

Indeed, a key cognitive value in the Way of Yellow is its capacity to hold, integrate, and embrace conflicting paradigms and paradoxes. Conflicting ideologies, such as reductionism and holism, spirituality and materialism, or even Marxism and libertarianism can all find their place and purpose in the Way of Yellow practitioner. The Way of Yellow sees the core insight and value of each opposing paradigm and ceases to become solely identified with one. By holding multiple contexts simultaneously, and adjudicating systems upon systems (called a 5th person perspective), the Way of Yellow can freely dawn the needed lens for the moment. I like to compare holding conflicting polarities to hydrotherapy: Going back and forth between hot and cold has shown to stimulate the immune system, improve general health and circulation, while just plain feeling good. Moving between paradigms is akin to an “ideological hydrotherapy,” in which our capacity for holding such perspectives is strengthened.

This capacity to hold multiple and conflicting perspectives leads to more nuanced, thoughtful, and holistic solutions—solutions that aspire to be practically effective, good for all of life, and beautiful in nature. In our current age of fake news, rank partisanism, and ideological polarization, the subtleties of nuance is more important than ever. By delving deeply into the “other side” and tapping its once unseen wisdom, our sense of fear decreases. By integrating what was once foreign, alien, and “other,” our irrational fears diminish as our “shadows” are made visible and brought to light. This type of inner work is central to the Way of Yellow and is what allows us to develop more nuanced and sophisticated assessments by militating against cognitive, confirmation, and ideological biases. Way of Yellow consciousness is constantly aware of the intrinsic wholeness of the world, and through inner work and reflection, can pave the way for wholeness, healing, and integration.

While still very much in the minority (only a couple percent of the adult population hovers at a Way of Yellow center of gravity), the leading-edge of Way of Yellow thinking is increasingly inspiring leaders and changemakers across the globe. People are finding new and innovative solutions to age old, “wicked” problems that are often multilayered, multi-contextual, and true to its name, very difficult to (dis)solve. The Way of Yellow, with its uniquely-connective capacity to synthesize multiple paradigms and perspectives, can generate holistic and nuanced solutions to such multidimensional and systemic issues. There has never been a more important time for this leading-edge as the Way of Yellow literally uses all of human history as a guide and resource to address the wicked problems and awe-inspiring possibilities in ourselves, cultures, societies, and nature. While I still continue to grow into my leading-edge of the Way of Yellow daily, the kuleana of this second-tier way of leadership is my continuing inspiration to lead humanity into a future of ever-increasing beauty, truth, and goodness.

References

Beck, Don, and Cowan, Chris. Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership and Change. Wiley-Blackwell, 1996.

Bennis, Warren. On Becoming a Leader. Basic Books, 2009.

Brooks, David. The Road to Character. Random House Publishing, 2015.

Clawson, Jim. Level Three Leadership: Getting Below the Surface. Prentice-Hall, 2008.

Dear, John. “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” Huffington Post, 25 November 2016. Accessed 1 February 2019 from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-dear/an-eye-for-an-eye-makes-t_b_8647348.html.

Esbjorn-Hargens, Sean and Gunnlaugson, Olen. (eds). Integral Education: New Directions for Higher Learning. SUNY Press, 2010.

Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Paradigm, 1748.

Kant, Immanuel and Humphrey, Ted. An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? Hackett Publishing, 1992.

Kegan, Robert. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Harvard University Press, 1998.

Kluckhohn, Florence. Dominant and Variant Value Orientations. In Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture. Clyde Kluckhohn and Henry A. Murray (eds). Alfred Knopf, 1953.

Lao Tzu & Mitchell, Stephen. Tao te Ching. Harper Audio, 1989.

Little, John. & Lee, Bruce. Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey. Warner, 2000.

Lyrics on Demand. Mississippi Ole Miss Fight Song, 2019. Accessed 18 January 2019 from https://www.lyricsondemand.com/miscellaneouslyrics/fightsongslyrics/mississippiolemissfightsonglyrics.html.

Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and Personality. Harper and Row, 1954.

Mill, J. S. On Liberty. Longman, Roberts & Green, 1869. Accessed 2019 February 4 from www.bartleby.com/130/.

Neville, Morgan. Won’t You be my Neighbor? Sundance, 2018.

Nietzsche, Friedrich & Hollingdale, R. J. (ed.). Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Penguin Publishing, 1961.

O’Keeffe, Dennis. Edward Burke. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009.

Olthuis, James, H. “On Worldviews.” Christian Scholars Review, 14, 1985, pp. 153–64.

Palmer, Parker. Let Your Life Speak: Listening to the Voice of Vocation. Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Scharmer, Otto. Leading from the Future as it Emerges. Berrett-Koehler, 2016.

Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. A. Strahan & T.Cadell, 1789.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Kant and Hume on Causality, 2018. Accessed 6 February 2019 from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-hume-causality/.

The Ethics Center. Ethics explainer: The harm principle, 2008. Accessed 9 January 2019 from http://www.ethics.org.au/on-ethics/blog/october-2016/ethics-explainer-the-harm-principle.

Thoreau, Henry David & Allen, Francis H. (1910). Walden: Or, Life in the Woods… with an Introduction and Notes by Francis H. Allen. Houghton Mifflin Company.