Ian Roth

Ian Roth

It is self-evident that the most useful education is one that facilitates learning-how-to-learn. While the reasons for past failures to provide such an education are undoubtedly multivariate, among them must certainly be counted the apparent difficulty of delivering such an education. The more bureaucratized and institutionalized the educational context becomes, the more this guiding principle must appear overly idealistic. Yet, considering the fundamental conundrum of education—that it is intended to prepare learners for a world that does not yet exist—this goal remains both pertinent and important. It is the intention of this paper to make that goal appear a bit more realistic, regardless of the context in which it is being pursued.

The central offering to be found here is a model of learning based on other such models. The research that supports this paper consists of a study of frameworks found across a variety of educational traditions and in the writings of notable educators and thinkers throughout history. The resulting meta-model is an attempt to address the difficulties inherent in learning-how-to-learn, or in facilitating this process for others, by distilling a wealth of cross-temporal, cross-cultural, and cross-disciplinary insights into a set of usable, coherent principles that enjoy context-independent applicability. It will be referred to as the trans-contextual learning model (TCLM).

Background

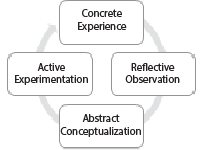

This is not the first learning meta-model to be proposed. Kolb (1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2009) described an experiential learning model (ELM) that drew on the work of William James (2018), and incorporated models proposed by Lewin (1942), Dewey (1938), and Piaget (1963). Largely in keeping with these models, Kolb’s meta-model consists of four sequential stages that comprise a learning spiral: concrete experience (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimentation (AE) (1984).

These four stages can be bifurcated into the dialectics of CE-AC whereby experience is grasped, and AE-RO whereby experience is transformed (Kolb & Kolb, 2009). The dialectical structure of learning is echoed by the ELM’s constituent models:

– Lewin places “…the conflict between concrete experience and abstract concepts and the conflict between observation and action” at the center (1984, p. 29).

– Piaget identifies the dialectical relationship between assimilation—wherein experience is interpreted so as to fit into existing concepts—and accommodation—wherein existing concepts are reimagined so as to make them consistent with experience (1963).

– Freire’s model depicts a two-stage process comprised of critical inquiry/reflection and world-transforming action (1970).

There can be little doubt that dialectical relationships are the foundations of all learning—as a mode of being, learning is an attempt to resolve what Senge identified as the creative tension occupying the distance between current reality and envisioned reality (2006). Despite this, the TCLM presented in this paper is neither two- nor four-part in construction. It posits three essential movements. This does not make it inconsistent with the models previously discussed. The dialectical back-and-forths they posit are the fundamental building blocks of learning. The TCLM is an attempt at a universal blueprint for how those blocks can be assembled in a progressive fashion. The major elements suggested by the other models are all represented; the relationships, while altered, are clearly recognizable; the spiraling character is preserved. But, whereas these models are meant to describe how learning takes place, the TCLM seeks to prescribe a set of enabling constraints intended to facilitate, rather than to elucidate, the learning process.

In that each of the sources reflected in this model were seeking to answer slightly different questions or to answer the same questions in different contexts (which amounts to the same thing), each formulation of the process and constituent stages possess their own idiosyncrasies. Though the focus of the paper is on the convergences of these models, their unique characteristics will also be briefly explored. If anything, acknowledging the disparateness of the thinkers and traditions here represented should serve to further impress the significance of what they all share.

The Trans-Contextual Learning Model

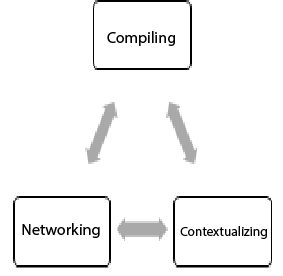

As mentioned, the TCLM consists of three central movements. There are as many names associated with these movements as there are thinkers and cultures that have employed them. In that this meta-model is meant to represent each of these traditions, I will employ terminology that is not native to any of them and, thereby, equally inclusive and representative of all of them. These meta-terms will be compiling, networking, and contextualizing.

The model is hierarchical in that compiled-learning is more fundamental than either the networked- or contextualized-learning of later steps, but the process it represents need not be engaged with unidirectionally. Strictly speaking, then, the process is not cyclical since cycles are determinatively sequential. It is, however, recursive and self-directing. The activities associated with contextualizing inevitably reveal spaces of insufficient learning that call the learner to re-engage with the other stages. Each of the three informs how the others can further contribute. The entire process can be inverted or proceeded through starting with the middle and progressing to the extremities because, in truth, each of the stages is equally the middle stage. A learner can freely move from a more fundamental stage to a more complex one, or from the more complex to the less so in accord with current challenges and perceived insufficiencies.

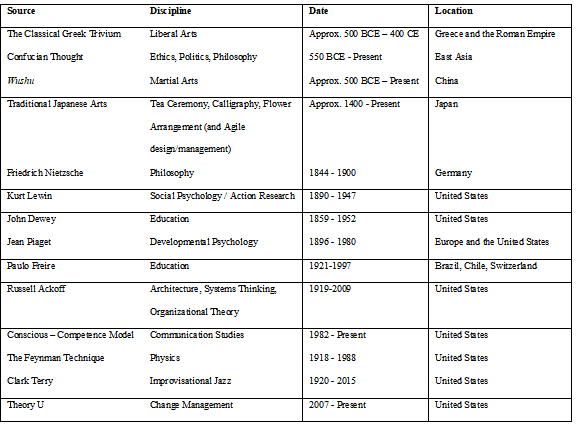

Table 1: Sources and their disciplinary, temporal, and geographic contexts

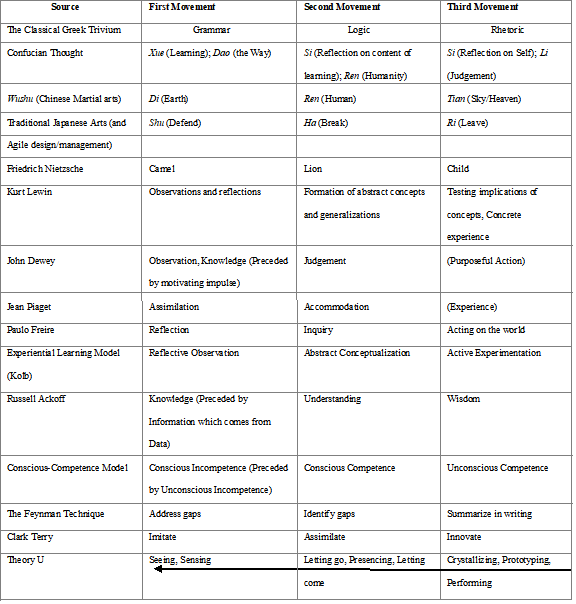

Table 2: Sources and their learning stages

Compiling

Instantiations. This stage is metaphorically represented by Nietzsche as being that of the camel (2005). As a beast of burden, the toil of the camel involves taking on and carrying baggage. In that Nietzsche was attempting to describe the stages of spiritual development, this baggage metaphorically represents the mores and customs of an established cultural order— values and thou shalts accumulated over a thousand years. But, given the extent to which his model aligns with the other traditions here represented, it can justifiably be understood as describing the learning process itself, in which case the camel would be taking on the accumulated knowledge of a field of study.

Nietzsche’s formulation aligns particularly well with that of Chinese wushu and the traditional Japanese arts in which the first movements are named di (earth) and shu (defending) respectively. This stage is characterized by strict adherence to established patterns. Quoting Aikido master Seishiro Endo, “In shu, we repeat the forms and discipline ourselves so that our bodies absorb the forms that our forebears created. We remain faithful to these forms with no deviation” (Pranin, qtd. 2005, para. 18). This statement is echoed by the imitate stage of musicianship during which the learner seeks only to make of him or herself a facsimile of the artist being imitated (Terry, 2015).

The uncritical acceptance of the forms is a function of the learner’s being conscious of his or her incompetence which makes it the second movement in the Stages of Competence model (Howell 1982). According to this model, it is preceded by the unconscious incompetence stage in which the potential learner is not even aware of what he or she does not know and, thus, has yet to begin the learning process. Knowing that one does not yet know makes acceptance of the established the only feasible option for reliably making progress.

The implications of this argument are advanced further by Confucius’s Xueji (Record of learning) in which novices are dissuaded from asking questions. “…novice learners should devote themselves first to acquiring the foundational knowledge. Otherwise… they may shortchange their learning by being impatient and opting for quick results,” (Tan, 2017, p. 9). Not knowing what one does not know implies that one also has little sense of how to advance one’s learning through questions and, thus, that haphazard questioning may do more harm than good.

Confucianism identifies two possible variations on each of the stages. The first stage can be either xue (learning) or dao (the Way) (Kim, 2003; Tan, 2015). The former is a more general term, whereas the latter is a normative prescription for being human (Hansen, 1989) and achieving cultural perfection (Tan 2017). As with Nietzsche’s formulation, Confucius’ treatment makes clear the trans-disciplinary applicability of this model.

According to the Trivium of the classical liberal arts, this is the stage of grammar (Joseph, 2002; Robinson, 2013; Sayers, 1947; Mitchell, Grenon, Fontainelle, Arvatu, Aberdein, Wynne, & Beabout 2016). The grammatical rules of the language one learns to speak are entirely inherited and powerfully prescribed–non-adherence constitutes error. There are exceptions to this, but they become possible only after this stage has been mastered. While in this stage, learners are often aware, even painfully so, of the ways in which their knowledge is insufficient. They recognize gaps of not-knowing, but may also not know where or how to fill those gaps.

The search for and identification of needed knowledge is a demanding, crucial process. This is reflected in Ackoff’s version of the tripartite learning process, which is prefaced by the stages of data and information in that order (1991). Neither is yet a part of the learning process, but they are the resources necessary for that learning process. The distinction between them is as follows: “Data are symbols that represent the properties of objects and events. Information consists of processed data, the processing directed at increasing its usefulness…. The difference between data and information is functional, not structural,” (1999, p. 170). The first stage of learning, which Ackoff labeled knowledge, requires the searching through and sorting of the available information into that which is useful in answering how-to questions–the most basic of inquiries. It is internalized through drilling–contextless practice that, due to its algorithmic nature, requires only that the learner follow a set of known steps to reach a determined conclusion (1991).

Being a social-technology intended to facilitate collective change, Theory U provides a different, though overall TCLM-consistent perspective on the learning process. It is comprised of seven steps. The first of these is ‘Downloading’ which is described as, “reenacting patterns of the past” (Scharmer, 2009, p. 244). With respect to the meta-model, this is a pre-learning stage as the patterns being re-enacted are those on which the learner has already come to rely. Downloading is followed by ‘Seeing’ and ‘Sensing’. The former consists of expressing one’s own knowledge, beliefs, and current enactment patterns, and of being open to hearing the points of views shared by others. This allows those involved to identify and suspend, to some extent, the influence of the past—to metaphorically empty their respective cups. It is followed by sensing wherein the learner identifies with the new points of view and comes to see his or her place in the system (Scharmer, 2009). With respect to the meta-model, these stages of Theory U suggest the importance of identifying what is already known as both a way to consolidate what is and to highlight what is needed. Since it is a process intended to facilitate systemic social change, the knowledge of one’s own role is a necessary precursor to that change (Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski & Flowers, 2004).

The collecting process can and should be facilitated by the other learning stages. Perhaps this is why Richard Feynman conceived of his process as beginning with what this meta-model portrays as the third stage (Gleick, 1993). Though it presumably follows some preliminary experience and/or learning, he began his formal process by defining and describing in writing, and using pictures and examples when appropriate, the lesson being learned, as though he were attempting to communicate it to a child. He would then work backwards to identify the description’s weaknesses (the second movement) and, finally, would seek to address those weaknesses with the required information before reworking his initial description in accord with the results of his learning effort (Gleick, 1993). The feasibility of this approach offers justification for the non-hierarchical, non-serial nature of the TCLM.

Principles. As the name implies, this step focuses on identifying, gathering, and making usable the information that one has reason to believe is pertinent to the intended learning. There are several ways in which the needed information can be identified. As the ELM suggests, experience ranks highly among these. The learner should reflect on any suitable experiences to identify what can be learned from them, including what can be learned about what still needs to be learned. As Argyris and Schon discovered (1974), much of a learner’s knowledge may be tacit in nature and not easily made explicit. Continued engagement and reflection are the only self-contained remedies for this; a bit of guidance or insight from another person can also be of great benefit.

The novice cannot identify crucial learning gaps as the experienced learner does and, with guidance if possible, should survey the field to reveal which practices, theories, principles, rules, etc. are considered foundational by those who already possess the desired expertise. This is the process of extracting information from data (Ackoff, 1991). For both experienced and novice learners, if a relevant teacher-student or master-apprentice style relationship exists, it is during this stage that pure transmission can be useful. This understanding runs counter to Freire’s unequivocally negative portrayal of banking-style education (1970). While I do not suggest that he wrongly identified the existence of a problem, the TCLM suggests that he incorrectly identified that problem as one of essence–the banking-style produces alienation–rather than of application–over-reliance on and imposition of the banking style produces alienation. When learning something new, a learner will not know what he or she needs to know, but may also be unaware that he or she needs to learn those things in order to advance. Someone in possession of both forms of knowledge and a desire to see the learner succeed can be a useful resource (Markman, 2012; Rice, 2003).

As a result of reflecting on experiences, surveying the field, and/or accepting input from those who know, the learner should have developed a sense of what knowledge is required to progress. For a beginning student of geometry, the most effectual place to start might be the basic formulas for determining area; someone new to tennis might begin by focusing on the development of functional forehand and backhand mechanics.

Having identified what needs to be learned, the learner next seeks to internalize those things. The compiling stage in not merely one of accumulation. The information must be transformed into knowledge (Ackoff, 1999)—something the learner comfortably possesses and employs. Whether the knowledge in question be a theorem or a forehand, such control is cemented through deliberate practice performed in a spaced, interleaved, and varied manner for an extended period of time (Ericsson, Krampe & Tesch-Römer, 1993; Brown, Roediger & McDaniel, 2014). The end result is a learner who has fit him or herself into the mold of existing knowledge.

Networking

Instantiations. The first movement supports the ability to apply the relevant information (e.g. using the appropriate formula to determine the area of a shape). It is during the second movement’s testing process that the learner develops the capability to do so—discovering when and in what contexts their abilities are useful (e.g. recognizing when the area of a shape is needed and which formula is appropriate for determining). This progression is echoed by the conscious competence of the Stages of Competence model (Howell, 1982). During this stage, the learner is actively choosing which knowledge to apply. The comprehension required to do this is what Ackoff called ‘understanding’ and it “…is conveyed by explanations, answers to why questions” (1999, p. 171). Actively choosing one process over another necessitates having a reason for that choice—an able-to-be-made explicit explanation to answer the question of why the choice was made as it was.

This movement often highlights irreconcilabilities in the accumulated information. Doing so is one of its primary functions. Discovering which pieces do not fit together and, in particular, which pieces cannot logically co-exist leads to a winnowing of the information. This is justified by an extension of the law of non-contradiction–namely, that good information will be consistent with other good information. By assembling the knowledge in this way, the learner is practicing the logic stage of the Trivium (Sayers, 1947; Robinson, 2013). Likewise, in the Japanese arts it is during this stage that, “…forms may be broken and discarded” (Pranin, 2005, para. 18). According to the Trivium, complimentary knowledge is identified through logical evaluation; difficult to spot errors and inconsistencies (e.g. begging the question) are as well (Robinson, 2013; Sayers, 1947). Soundly constructed strings of premise-knowledge lead to reliable conclusions that are themselves additions to the known. In shu-ha-ri, experimentation and self-as-context reconsideration serve to identify the breakable and discard-able.

The act wherein the established is combined to produce the novel is that of the lion, Nietzsche’s second metamorphosis (2005). “…why is there a need of the lion in the spirit? …to create freedom for oneself for new creating…and give a sacred ‘No’ even to duty: for that, my brothers, the lion is needed” (2005, p. 26). This is the stage during which the limitations of the previously accepted order are rejected. This is not to say that they are no longer of importance; through reinterpretation and re-combination, they serve as the vehicle needed to transport the learner to what is ultimately discovered–that the limits of what is known are not the limits of what can be known.

The second stage according to Japanese traditional arts is described in this way: “…in the stage of ha, once we have disciplined ourselves to acquire the forms and movements, we make innovations” (Endō, 2005, para. 18) In the Confucian tradition, this is the first stage of si (reflection on learning) which follows xue (Kim, 2003). Confucius argued that combining learning with reflection was not only an educational necessity, but an ethical one. “Learning without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous” (2011, p. 7). Presumably, this is more so the case with dao and ren (humanity). Confucius states that it is people who enhance dao, not the dao which enhances people (Confucius, 2011; Tan, 2017). This is accomplished through ren as expressed in li (judgements), which constitute the third learning stage. Thus, dao must be interpreted through ren in order to determine its various roles and implications.

Theory U also suggests that during this stage the learner seek connection at a deeper level, though the object of this connection is not humanity, but what is trying to emerge (Scharmer, 2009). This is consistent with both the implication-focused and creative aspects of network-learning that have already been discussed. It is accomplished, first, by letting go of previously identified limitations and intentions; second, by being fully and intentionally present—metaphorically awash, but floating in the dynamic, behavioral, and emergent complexities of the system; and, third, by letting come what wants to be born (Scharmer, 2009).

Principles. The second of the stages involves ordering, fitting together, and otherwise making or breaking connections between the knowledge previously gathered by the learner. It is during this movement that similarities are recognized and, thereby, that ‘information’ is re-categorized as ‘kinds of information’ based upon the relationships and roles that come to define it. Differences play a no less important role in this sorting process. The resulting networks of learning are not equivalent to chunks. Chunking, defined as a process during which discrete pieces of information are fit together to form a meaningful whole (Neath & Surprenant, 2003), takes place during the collecting stage. But, the networking phase can inform the chunking process as the learner considers and experiments with the knowledge they already possess, seeking to create combinations and to understand each piece’s combinatorial capacity.

This is equally a movement characterized by the discarding of previously formulated conceptions. Inconsistencies within a network of knowledge must be identified and resolved. This can mean the discarding of one or all of the offending elements, or that they can be salvaged through reinterpretation. Argyris and Schon point out that the possibility that “…the difficulty in learning new theories of action is related to a disposition to protect the old theory-in-use” (1974, p. viii). Learners do not enter any learning process as blank slates either in terms of collected or networked knowledge and, of the two, faulty networked knowledge is more likely to prove problematic. Not only can the calcification of its existing networks prevent useful, contradictory networking from occurring, but it can make potentially useful, good information invisible or unattractive. One piece of compiled information is easier to identify as problematic and to uproot than is a network of information.

Much of this movement depends on attempts at applying the accumulated information in a non-algorithmic manner. In other words, whereas compiled information, such as the step-by-step processes that constitute algorithms, can be applied, their prescriptive nature does not promote the active organizing of that information. Such organization can only be accomplished by repeatedly attempting heuristic-style problem solving and, thereby, developing strategies proven through trial and error. This is not, however, to suggest that network-learning is a product of solely the conscious and explicit. Whereas the collecting stage is very much so characterized by a focused mindset, much of the best work of the networking stage is accomplished through diffuse thinking and unconscious processes (Oakley, 2014).

Contextualizing

Instantiations. Nietzsche’s third stage of metamorphosis is that of the child, who is able, in the space produced by the lion’s rejection of the established boundaries, to create something new (2005). For the Japanese arts, this stage (ri) is the one in which, “…we completely depart from the forms, open the door to creative technique, and arrive in a place where we act in accordance with what our heart/mind desires, unhindered while not overstepping laws” (Endō, 2005). This description emphasizes the unconscious competence of the learner who is no longer following prescribed rules, nor even working to test and overcome their implied limitations, but who is giving personal expression to the principles that form the foundation of the practice (Howell, 1982), just as one does through musical improvisation and innovation (Terry, 2015). As the second portion of the si stage (reflection on self) suggests, this involves bringing the self into focus by asking questions related to identity and values (Kim, 2003).

Neither the drills of the first stage nor the questions of the second require any consideration of values (Ackoff, 1999)–the work they inspire can only be evaluated, respectively, as correct or incorrect and right or wrong. Once values are taken into consideration, the nature of the actions taken changes dramatically. They are now good or bad and reflective of the actor in a much more revealing way. They also have the potential as li (judgments) founded on ren (humanity) to expand dao (the Way) (Tan, 2015). By advancing one’s learning, one becomes able to advance learning as a collective endeavor. At this level of analysis, then, the dao is not a prescription for personal and cultural perfection, but for a process of iteration towards perfection.

The application of grammar and logic through the practice of rhetoric also has ethical implications (Aristotle, 1954; Andoková & Vertanová, 2016). It can be used for good or ill, though such judgements are a function of the values possessed by the one judging. The use and outcomes of the Trivium’s three steps are as follows. Use of grammar is correct or incorrect, respectively producing comprehensibility or incomprehensibility. Use of logic is sound or unsound, resulting in correctness or (potentially) incorrectness. Use of rhetoric is effective or ineffective with outcomes that are, not always respectively, good or bad.

Just as rhetoric is concerned with outcomes, the third stage of Theory U consists of Crystallizing, Prototyping, and Performing—three sub-stages that are directed at producing results (Scharmer, 2009). The knowledge of the second stage is first concretized as something actionable. This leads to strategic, microcosmic prototypes—iterative attempts to realize various aspects of the vision. And, finally, to the performing stage in which the product of the iterations is given an opportunity to produce results.

The seeming outlier here and, in several ways, throughout this paper has been the Feynman method. This method begins with what the other traditions consider the third stage. It asks that the learner attempt to summarize and explain the learned content in writing as though seeking to teach it to a child (Gleick, 1993). This appears to fall quite a bit short of the complexity and grandeur claimed by some of the other traditions and, in some ways, it does. It is best suited to serve as a pedestrian shortcut to achieving high-level competence rather than as a model for a lifetime’s pursuit of mastery or spiritual transformation. It could rightly be argued that the composition of this written content description is an act of creation that will bear the imprints of the composer and his or her value-based judgements about the material. And the imagined goal of communicating the content to a young person, though in this case used as a guideline and clarifying device, is a variation on communicating and teaching as instantiations of the third movement found, respectively, in the Trivium’s rhetoric and Ackoff’s wisdom (Aristotle, 1954; Ackoff, 1999). Though not a problem in context, it is one with context that offers a variety of possible solutions. And more than the other traditions, this method makes explicit its post-third movement progression. The evaluation of the third movement’s product constitutes the second movement, and the results of this evaluation guide the targeted accumulation of the first movement.

While this method appears to be a reversal of the other formulations, its viability is one reason the TCLM encourages flexibility and iteration. While comprised of more complex and consequential applications of what has been learned, the third movement is never an endpoint. In addition to what it proactively accomplishes, it also always makes apparent the areas of development that must be addressed if more is to be accomplished in the future. The Feynman method, then, is less a reversal than a miniaturized learning cycle that can be more easily targeted at specific content and that can exist within a larger, more comprehensive learning process.

Principles. The third movement is one in which a problem is addressed, and learning is furthered by, in a sense, turning away from the learned content itself. Compiling is driven by reflection on what is known and what needs to be known; networking consists of reflecting on the meaning and implications of what has been collected; contextualizing occurs when this networked learning is reflected onto and comes into contact with the world. This movement relies on the natural progression from learning to acting, from acting to creating change, and from creating change to being changed. The actor is part of the context in which the learned exists and with respect to which it is influential. During this movement, the sufficiency of the assembled, networked information is tested again, for the first time as a system in and among other systems.

The world-directed-action this entails takes the form of identifying a problem for which the solution is unknown (as must be the case for any true problem) and working to arrive at a solution through the application of previously developed understandings and individual contributions made possible by the unique perspective, developed through network-learning, that the learner brings to the learned.

Among the activities that may satisfy the criteria of the owning movement are writing about, teaching, or debating the new learning. There are of course many others, but each of these three, properly engaged with, demands the actor apply entire structures of what he or she understands in the attempt to reach an unknown solution to an often vaguely defined problem. To employ teaching as an example, is it the case that the teacher’s problem is how to raise the test scores of his or her students? Or is it to ensure they can act as responsible citizens? Or to help them develop the skills they will need for career success? And even should the starting problem be clearly defined, its possible solutions are characterized by extreme variety and equifinality. As a result, the solution to a true problem is not the answer produced by the solving it (this is merely information), but the creative and transformative process whereby the learner becomes capable of producing that solution.

Conclusion

The essence of this meta-model is as follows:

Compiling- identify needed information; chunk; internalize; drill; answer ‘how’ questions

Networking- categorize by role/function; experiment with new combinations through exercises; identify and resolve contradictions; seek limits of the known; answer ‘why’ questions

Contextualizing- transmit; embody; identify and address problems; answer ‘to what end’ questions

Having provided this, it should be noted that what defines each stage is less the essential qualities of a given action than the intentions that motivate it and the relationships with other actions that inform it.

This model is representative of a broad range of theories and traditions. While there are no studies at this time that support its effectiveness, the number and disparateness of the times, locations, and disciplines that have all converged on what is essentially the same model of learning is a convincing, if not exactly empirical, form of empirical evidence. Having said that, there is an element to this model that should be considered less representative and, while potentially innocuous-seeming, it is significant.

Whereas many of the learning models here distilled are cyclical in nature, the TCLM permits and encourages free movement between its different stages. It recognizes that the support these stages offer to one another does not flow unidirectionally, but that the feedback obtained when operating in any one of them can be of use when engaged in any other. In learning-how-to-learn, one must be able to identify, based upon such feedback, which stage of learning is most attractive at any given time and to switch modes accordingly.

The importance of this facet is that it makes the TCLM less prescriptive and, thus, more flexible. It can be more readily applied in a variety of contexts, whether the nature of the learning be self-directed or institutional.

A final point that deserves mention is that the TCLM is a model for learning, not for deciding what to learn. To rework Peter Drucker’s formulation, the TCLM can help learners to learn the right way (efficiency), but it is not a guarantee that they will be learning the right things (effectiveness). The pre-learning phase, then, should always consist of ensuring that what is to be learned is what should be learned, for efficiently learning that which is unnecessary is a reliably ineffective thing to do.

References

Ackoff, R. (1991). Ackoff’s Fables: Irreverent Reflections on Business and Bureaucracy. New York: Wiley.

Ackoff, R. (1999). Ackoff’s best: His classis writings on management. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Andoková, M. & Vertanová, S. (2016). Is rhetoric ethical? The relationship between rhetoric and ethic across history and today. Graecolatina et Orientalia, 37-38, pp. 133-145.

Argyris, C. & Schön, D. (1974). Theory in Practice Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Aristotle. (1954). Rhetoric. W. R. Roberts (Trans.) New York, NY: Random House.

Brown, P., Roediger, H. & McDaniel, M. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Confucius. (2016). The analects. Legge, J. (Trans.) Pantianos Classics.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Macmillan Company.

Ericsson, K. Anders, R. K. & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100 (3), pp. 363-406.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books.

Gleick, J. (1993). Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman. New York, NY: Vintage.

Hansen, C. (1989). Language in the heart-mind. In Robert E. Allison (ed.) Understanding the Chinese mind: The philosophical roots. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, pp. 75 – 124.

Howell, W. (1982). The empathic communicator. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

James, W. (2018). Essays in radical empiricism. Whithorn, Scotland: Anodos Books.

Joseph, M. (2002). The trivium: The liberal arts of logic, grammar, and rhetoric. Philadelphia, PA: Paul Dry Books, Inc.

Kim, H. K. February, (2003). Critical thinking, learning and Confucius: A positive assessment. In Journal of philosophy of education, 37 (1), pp. 71-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.3701005

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. & Kolb, A. (2009). The learning way: Meta-cognitive aspects of experiential

learning. In Simulation & Gaming, Vol. 40 (3), pp. 297-327.

Lewin, K.(1942). Field theory and learning. In Yearbook of the national society for the

study of education, 41. DOI: 10.1037/11335-006

Markman, A. (2012). Do you know what you don’t know? In Harvard Business Review.

Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2012/05/discover-what-you-need-to-know

Mitchell, J., Grenon, R., Fontainelle, E., Arvatu, A., Aberdein, A., Wynne, O. & Beabout, G.

(2016). Trivium: The classical liberal arts of grammar, logic & rhetoric. Somerset, United Kingdom: Wooden Books.

Nietzsche, F. (2005). Thus spoke Zarathustra. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Classics.

Neath, I. & Surprenant, A. (2003). Human memory. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Oakley, B. (2014). A mind for numbers. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Piaget, J. (1963). The origins of intelligence in children. New York, NY: W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc.

Pranin, S. (2005). An interview with Endō Seishirō Shihan. Nishina, D. & Hideo, A.

[Trans.] In Aiki News, Japane No. 144 http://members.aikidojournal.com/private/interview-withseishiro-endo-2/

Rice, J. (2003). Teacher quality: Understanding the effectiveness of teacher attributes.

Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Robinson, M. (2013). Trivium 21c: Preparing young people for the future with lessons from

The past. Carmarthen, United Kingdom: Independent Thinking Press.

Sayers, D. (2017). The Lost Tools of Learning. Louisville, KY: GLH Publishing.

Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Senge, P., Scharmer, C. O., Jaworski, J. & Flowers, B. S. (2004). Presence: Human

purpose and the field of the future. New York, NY: Crown Business.

Scharmer, C. O. (2009). Theory U. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Tan, C. (2015). Beyond rote-memorisation: Confucius’ concept of thinking. In

Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 47(5), pp. 428-439.

Tan, C. (2017). Confucianism and education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of

Education. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.226

Terry, C. (2015). Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry. Oakland, CA: University of

California Press.

About the Author

Ian M Roth currently works as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Foreign Studies at Meijo University, located in Nagoya, Japan. He earned his Ph.D. in Organizational Systems program from Saybrook University. In addition to questions of linguistic evolution, his research interests include educational systems design and emergence-based pedagogies.