Complexity Leadership: An Overview and Key Limitations

Barrett C. Brown

Abstract

An overview of the complexity leadership literature is provided. This includes a history of complexity theory and its core concepts, the central propositions of complexity leadership, a review of six prominent frameworks, and a summary of practitioner guidelines. The article also discusses two key limitations to complexity theory: the need to supplement it with other epistemologies and leadership approaches, and the importance of recognizing that its sustained execution likely requires a developmentally mature meaning-making system. The conclusion is that complexity leadership offers a fresh and important way of perceiving and engaging in the management of complex organizational behavior, one which may help leaders to address the most pressing and complex social, economic, and environmental challenges faced globally today.

Complexity Leadership

Complexity leadership was introduced by Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001). It is based upon the application of complexity theory to the study of organizational behavior and the practice of leadership. In the 1990s, researchers drew from complexity theory studies in physics, chemistry, biology, and computer science to cultivate novel insights about their fields. Such research was initially focused on the social sciences in general (Goldstein, 1995; Marion, 1999; Nowak, May, & Sigmund, 1995), but soon thereafter complexity theory was applied to organizational processes (Anderson, 1999; McKelvey, 1997).

This article offers an overview of the complexity leadership literature. To understand complexity leadership requires knowledge of the fundamentals of complexity theory. The first section of this article briefly describes the history and lineage of complexity theory and defines some of the important concepts from it that are applied in the field of complexity leadership. This if followed by a summary of the core concepts of complexity leadership and a review of six complexity leadership frameworks. The article continues with an overview of guidelines for putting complexity leadership theory into practice, and concludes with a discussion of two key limitations to its application.

Complexity Theory

The science of complexity theory concerns the study of complexly interacting systems (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). Complexity theory has been defined the “study of behaviour of large collections of…simple, interacting units, endowed with the potential to evolve with time” (Coveney, 2003). While the entire theory is more complex than this, this definition is useful as it encompasses three fundamental characteristics of complex systems: they involve interacting units, are dynamic, and are adaptive. In essence, complexity theory is about (1) the interaction dynamics amongst multiple, networked agents, and (2) how emergent events – such as creativity, learning, or adaptability – arise from these interactions (Marion, 2008).

Complexity theorists inquire into how such systems engage with each other, adapt, and influence things like emergence, innovation, and fitness (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). Complexity theory developed out of myriad sources, many of which arose during World War II. However, nine main, interrelated research strands form the lineage of its contemporary expression. Each of these traditions offers core constructs that are essential to the overall theory. Systems thinking offers the concepts of boundaries and positive and negative feedback loops. Theoretical biology frames organizations as organic, evolving, whole systems. Nonlinear dynamical systems theory developed the notions of attractors, bifurcation, and chaos. Connectivity and networks were developed in the purely mathematical field of graph theory. Complex adaptive systems theory contributes the idea of evolving, adapting systems of interacting agents. Finally, the concept of emergence of novel order arose across through work on several fields/constructs: phase transition, Turing’s morphogenetic model, synergetics, and far-from-equilibrium thermodynamics (Goldstein, 2008).

A full review of complexity theory is beyond the scope of this article, but the following key concepts are explained below, as they are instrumental for understanding complexity leadership: complex vs. complicated; characteristics of a complex system; interaction; dynamic; adaptation; mechanisms; self-organized criticality; dissipative structures; emergence; and complex adaptive systems.[1]

Complex vs. Complicated

In the complexity sciences, the term “complex” does not mean the same as “complicated.” A system is complicated if each of its individual components or constituents can be described (even if there is a huge number of them). For example, computers or jumbo jets are complicated systems. A system is complex if its relationships cannot be explained fully by merely analyzing its components because they are dynamic and changing. The brain, for example, is a complex system (Cilliers, 1998 cited in Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2009). The term complexity is meant to impart the sense of deep interconnectedness and dynamic interaction that results in emergence within and across complex adaptive systems (described below). Complexity generates novel features, often called emergent properties. Other examples of complex systems that generate emergent properties due to being richly interactive, nonlinearly dynamic, and unpredictable are the Brazilian rainforest, natural language, and social systems (Cilliers, 1998; Snowden & Boone, 2007; Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2009).

Characteristics of a Complex System (Snowden & Boone, 2007)

Complex systems incorporate myriad interacting elements. The interactions between these elements are nonlinear and minor changes can cascade into large-scale consequences. Such systems are dynamic, with a whole greater than the sum of its parts. It is not possible to impose solutions or order upon them; rather, such novel forms arise from the circumstances within them (called emergence – discussed below). The elements of complex systems evolve with one another, integrating their past with the present, and their evolution is irreversible. Due to the constant fluctuations and changes of external conditions and connected systems, complex systems are not predictable, although they may seem ordered and predictable in retrospect. As such, no forecasting or prediction of their behavior can be made. This is due to the fact that individual elements and the system itself constrain one another over time. Such mutually constraining behavior is different than in ordered systems in which the system constrains the elements, or in chaotic systems which have no constraints.

Interaction

Complexity theorists study the “patterns of dynamic mechanisms that emerge from the adaptive interactions of many agents” (Marion, 2008, p. 5). When sentient agents (like humans in an organization) interact, they change due to the influence of relationships, interdependent behaviors, and the emergence of subsets of agents that engage one another interdependently. The structures, dynamic behaviors, and patterns that arise from these complex interactions become unrecognizable when perceived as linear combinations of the initial actors. These interactive behaviors and outcomes ultimately create feedback loops with each other, leading to effects becoming causes and influence arising from extensive chains of effect.

Dynamic

Complexity does not refer to static events. Rather, it concerns a dynamic process that consistently changes its elements and brings forth new things in a process called emergence (described below). While there is global stability and resilience within complex systems and complex behavior, they are fundamentally defined by change.

Adaptation

Adaptation refers to a complex system’s ability to strategically change or adjust in response to individual or systemic pressures. Adaptation arises at two levels, the individual and the aggregate. Individual adaptation concerns local stimuli and individual preferences. Individual adaptations amongst agents in a system can interact with each other, resulting in compromises that simultaneously serve the individual and the collective, thus forming aggregate adaptation.

Mechanisms

In general, mechanisms are processes that result in given outcomes (Hëdstrom & Swedberg, 1998, as cited in Marion, 2008). There are certain, universal mechanisms that drive complex dynamics. When change occurs, it is these mechanisms at work. Complex mechanisms are emergent behavior patterns, universally available, that enable a dynamic mix of causal chains and agents. An aspect of complexity theory is to identify and describe complex mechanisms and the patterns that arise from their interaction. There are four key complex mechanisms. First, correlation arises through the interaction of agents as they share part of themselves (technically called their “resonance”, but loosely can be understood as their worldview, assumptions, beliefs, preferences, etc.). Correlation brings about bonding and aggregation, which is the second mechanism. Aggregation represents the clustering of multiple agents due to the development of shared or interdependent resonances. Autocatalytic mechanisms are the third type. These are emergent structures and beliefs that catalyze or accelerate other mechanisms. For example, deviant behavior like looting can be autocatalyzed by rioting behavior. The fourth key mechanism is nonlinear emergence. This mechanism is experienced as a sudden shift in dynamic states. An extreme example is the demise of the Soviet Union; another would be the transition of water from liquid to solid. Emergence will be further discussed below.

Self-Organized Criticality

Self-organized criticality (Bak & Tang, 1989; Kan & Bak, 1991) and far-from-equilibrium dissipation (Prigogine, 1997) are two causative mechanisms that lead to nonlinear emergence. Self-organized criticality refers to instances in which a minor event can lead to chaos, driving large interactive systems to a critical state (Kan & Bak, 1991). Within complex, interacting systems of many agents, it represents sudden, unexpected shifts in structure or behavior. These emergent shifts are not “caused”, but rather happen due to the dynamic, random movements within complex systems. They occur as these complex systems are randomly exploring and come within range of – and “fall” into – a complex attractor. Dramatic shifts in the stock market or the onset of looting in riots are examples of these attractors that draw in systems that come close enough to their basins of attraction. Criticality cannot be influenced by external agents, such as leaders or environmental pressures.

Dissipative Structures

Dissipative structures are the order that emerges from the dissipation of energy. Typically, dissipation refers to the entropy and deterioration of order that results with the release of energy. The creation of order is normally associated with increased energy. Prigogine (1997), however identified dissipative structures that do not result in deterioration, but an increase in order with the release of energy. An example is when oil is heated slowly. For some time it demonstrates little change (no new order). Once the oil reaches what Prigogine (1997) called a “far-from-equilibrium” point – in which the energy builds to an unstable level – the oil molecules release energy, break the tension, and shift into a gentle boiling roll. As opposed to criticality, dissipative structures can be influenced by external agents, like leaders and environmental pressures.

Emergence

Emergence is “a sudden, unpredictable change event produced by the actions of mechanisms” (Marion, 2008, p. 9). It is a type of naturally occurring change and subsequent stabilization into a new order that is “free” – meaning that it does not require external energy to happen. It can result in dissipative structures. When complex systems are dynamically interacting, they often generate many low-intensity emergent changes; occasionally they experience a high-intensity change. These changes are different than those which arise through steady, step-by-step trajectories from known beginnings through predictable outcomes. Emergence arises through interaction and energic pressure as opposed to the actions of any lone individual. It is the dynamic actions of mechanisms that generate it, rather than the constant, predictable effect of variables.

Complex Adaptive Systems

The complex adaptive system (CAS) is a very important element in both complexity science and complexity leadership theory. It is the basic unit of analysis in both. According to two prominent researchers (Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2009, p. 631), complexity leadership is about leadership “in and of complex adaptive systems, or CAS” (Cilliers, 1998; Holland, 1995; Langston, 1986; Marion, 1999). CAS are open, evolutionary aggregates – neural-like networks – of interacting, interdependent agents who are cooperatively bonded by a common goal, purpose, or outlook (Cilliers, 1998; Holland, 1995; Langston, 1986; Marion, 1999; Uhl-Bien, Marion, & McKelvey, 2007). Arising naturally in social systems, CAS learn and adapt rapidly and are capable of creative problem solving (Carley & Hill, 2001; Carley & Lee, 1998; Goodwin, 1994; Levy, 1992; as cited in Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007). Complexity theorists essentially frame organizations as complex adaptive systems that are composed of heterogeneous agents that interact and affect each other, and in the process generate novel behavior for the whole system (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001).

With this review of the key concepts in complexity theory, I now turn to a review of some of the key findings and theoretical constructs arising from the research of leadership through the lens of complexity sciences.

Complexity Leadership: An Overview of Core Concepts and Frameworks

The field of studying leadership through the perspective of complexity is young (Panzar, 2009). Nonetheless, over the past decade, a group of researchers have focused on reframing and advancing the field of leadership through the use of the complexity sciences (Goldstein, Hazy, & Lichtenstein, 2010; Hazy, Goldstein, & Lichtenstein, 2007; Lichtenstein & Plowman, 2009; Lichtenstein, et al., 2006; Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001; McKelvey, 2008; McMillan, 2008; Plowman & Duchon, 2008; Stacey, 1996, 2007, 2010; Stacey, Griffm, & Shaw, 2000; Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2008). This section will provide additional historical context, review some of key insights of the field and briefly present six prominent frameworks by these researchers.

Complexity leadership theory emerged in response to perceived limitations in existing leadership theory. Much leadership theory is based in a bureaucratic framework representational of the industrial age in which it was developed. This includes the assumption that goals are rationally conceived and that the achievement of these goals should be done through structured managerial practices. As a result, much of leadership theory focuses on how leaders, amidst formal and hierarchical organizational structures, can better influence others toward desired goals. The core issues within such a leadership paradigm have then become motivating workers regarding task objectives, ensuring their efficient and effective production, and inspiring their commitment and alignment to organizational objectives (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Zaccaro & Klimoski, 2001, as cited in Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007).

Fundamentally, there is a core drive toward top-down alignment and control in this model. The traditional bureaucratic mindset that has developed as a result of this paradigm has demonstrated limited effectiveness with the rise of the Knowledge Era and the complexities of the modern world (Lichtenstein, et al., 2006). The Knowledge Era is characterized by the forces of globalization, technology, deregulation and democratization collectively creating a new competitive landscape. In such an environment, learning and innovation are vital for competitive advantage (Halal & Taylor, 1999; Prusak, 1996, as cited in Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007), and control is arguably not possible or sustainable. Complexity leadership is proposed as a framework for leadership in the fast-paced, volatile, and uncertain context of the Knowledge Era (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). It is, its various proponents contend, a needed upgrade to leadership theory to reflect our shift out of the Industrial Era (Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007).

Rather than focusing on top-down control and alignment, complexity leadership theorists argue that leaders should temper their attempts to control organizations and futures and instead focus on developing their ability to influence organizational behavior so as to increase the chances of productive futures (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). The fundamental concept underlying complexity leadership is that, under conditions of knowledge production, informal network dynamics should be enabled – and not suppressed or aligned (Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007). Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001) contend that leadership success is not dependent upon the charisma, strategic insight, or individual power of any given leader. Rather, it is attributable to the capacity of the organization to be productive in mostly unknown, future states. Leaders must therefore foster the conditions that develop that organizational capacity, focusing on understanding the patterns of complexity and manipulating the situations of complexity more than results. Specific recommendations are discussed below for how to do this. In a broad sense, though, leaders should create the conditions for bottom-up dynamics, leave the system essentially alone so that it can generate positive emergence, and provide some basic control to keep the system focused (i.e., broader goals and a vision) (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001).

Lewin and Regine (2003, as cited in Panzar, 2009) agree with this overall description of the new type of leadership required. For them, leaders need to move beyond setting an organizational vision and mobilizing around it. Successful long-term strategies are those that emerge from the continuous, complex interactions among people. As a result, leaders need to stop trying to control individual outcomes and instead shift their focus to the interactions with the intention to create the healthy conditions for people to self-organize around relevant issues. To do this requires leaders to change their perspective to see the organization as a complex adaptive system that unfolds, fluctuates and emerges. This shifts a leader’s attention from trying to direct people to serving the flourishing of dynamic interactions within the organization.

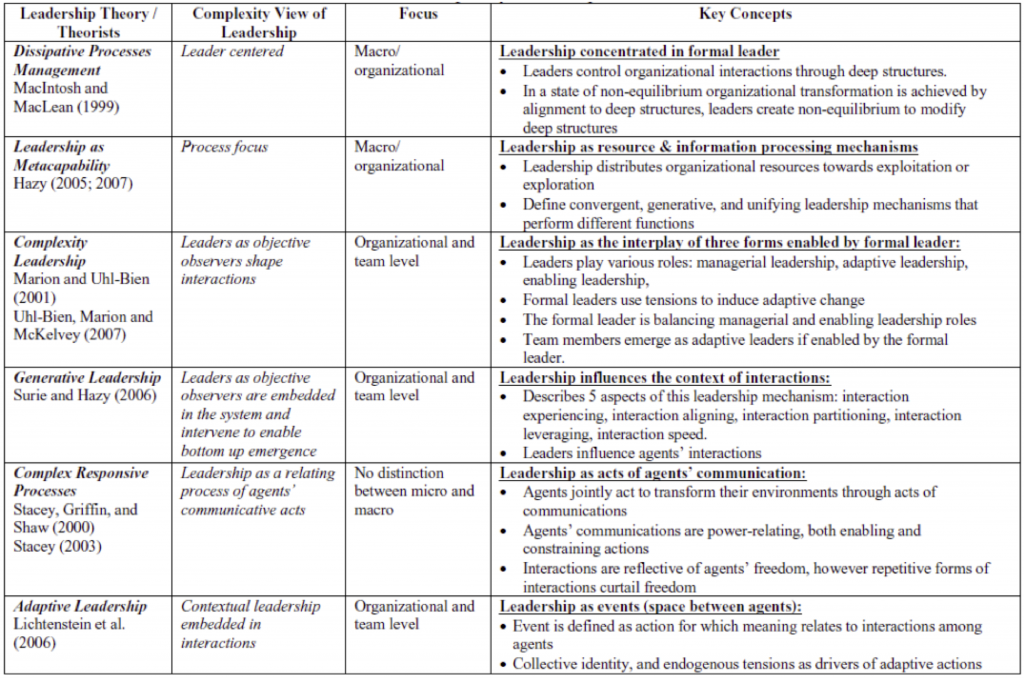

Complexity leadership has been approached from a variety of directions. Table 1, reproduced from Panzar (2009), offers a distillation and comparison of six important frameworks for studying and understanding leadership within a complexity worldview. Table 1 is followed by a brief overview of each framework.

MacIntosh and MacLean (1999) developed one of the first frameworks for organizational transformation based upon complexity sciences, specifically grounded in the concept of dissipative structures. They describe a specific, three-stage sequence of activities that support effective transformation. First, the organization articulates and reconfigures the rules that underpin its deep structure, thereby “conditioning” the outcome of the transformation process. Second, steps are taken to shift the organization from its current equilibrium. Third, the organization moves into a period where the dominant focus of management attention is on positive and negative feedback loops. Their contention is that this management of the organization’s deep structure enables influence over the otherwise unpredictable self-organizing processes.

Hazy’s (2005, 2007) framework for organizational change is grounded in complexity theory as well as other disciplines. His approach is process-focused as opposed to MacIntosh and MacLean’s (1999) leadership focus (Panzar, 2009). Hazy strove to identify the general principles that relate the organizational process of leadership with an organization’s sustaining social processes. Organizational leadership in this case is framed as a meta-capability that modifies or extrapolates the system’s other capabilities. Hazy explicitly inquired into how such a meta-capability operates within a social system and its potential impact on performance and adaptation through various environmental changes. By using system dynamics modeling, he found that different patterns of leadership – either transactional or transformational – did emerge depending on the environment. Out of this research, Hazy developed a leadership and capabilities model able to test hypotheses about leadership and the relationships between it and the organization’s social processes (cf. Goldstein, et al., 2010; e.g., Hazy, 2008). He has also used this framework to measure leadership effectiveness within complex socio-technical systems (Hazy, 2006).

A third framework called adaptive leadership was developed by a group of prominent complexity leadership researchers (Lichtenstein, et al., 2006). With this framework, they shift the traditional focus from that of leaders operating in isolation to influence their followers to that of being fundamentally interactive in nature. Leadership from this perspective therefore emerges out of interactions and events, out of the interactive spaces between people and ideas. Leadership from this adaptive perspective is framed as a complex dynamic process transcending individual capacities, drawing from the interaction, tension, and rules that govern changes in perception and understanding. Each leadership event is an action segment whose meaning is derived from the dynamic interactions of those who produced it. These researchers also developed a methodology analyze these leadership events.

Two parallel theoretical streams developed off of the adaptive leadership framework, leading to two more frameworks. In the first instance, Surie and Hazy (2006) build upon the adaptive leadership construct (Lichtenstein, et al., 2006) to develop a framework called generative leadership. This is a leadership approach that creates the context for stimulating innovation in complex systems. They contend that generative leadership is a process for managing complexity and institutionalizing innovation that balances connectivity and interaction between individuals and groups. Generative leaders do not focus on developing individual traits or creativity amongst those they work with, but rather create the conditions that nurture innovation. The authors describe five distinct aspects of agent interaction that they claim are leadership mechanisms: interaction experiencing, interaction aligning, interaction partitioning, interaction leveraging, and interaction speed. Their work demonstrates how leaders can leverage these mechanisms to catalyze the environment for innovation to arise.

Hazy has collaborated with Lichtenstein and Goldstein to write two mainstream leadership books that flesh out the concept of generative leadership and its application (Goldstein, et al., 2010; Hazy, et al., 2007). In their latest book (Goldstein, et al., 2010), they introduce the term “ecologies of innovation” to reflect the system-wide set of processes and interactions within complex adaptive systems that foster innovation. They then build upon ecological and complexity sciences to show how leadership can cultivate these ecologies of innovation.

In the second theoretical stream building upon the adaptive leadership framework (Lichtenstein, et al., 2006), Marion and Uhl-Bien (2007) draw upon it and their earlier work (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001) to present a (fifth) framework for the study of complexity leadership theory (CLT). This framework is also at the core of a business book on complexity leadership (Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2008). They define complexity leadership theory as a “leadership paradigm that focuses on enabling the learning, creative, and adaptive capacity of complex adaptive systems (CAS) within a context of knowledge producing organizations” (Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007, p. 298). CLT is a change model of leadership that helps leaders to tap into the informal dynamics within an organization as part of the process of designing robust, dynamically adapting organizations (Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2009).

The framework for CLT is built around three leadership functions: adaptive, administrative, and enabling. Adaptive leadership refers to actions that emerge as CAS interact and adjust to tension, such as constraints or disturbances. These actions are not acts of authority, but an informal emergent dynamic. They can be adaptive, creative or learning in nature, and can occur anywhere from the boardroom to a workgroup of line workers. Administrative leadership concerns the actions of those in formal managerial roles to coordinate and plan activities to achieve prescribed outcomes. This includes vision-building, resource allocation, conflict and crisis management, and organizational strategy management. Its focus is on alignment and control and is exemplified by hierarchical and bureaucratic functions. Enabling leadership concerns efforts to “catalyze the conditions in which adaptive leadership can thrive and to manage the entanglement…between the bureaucratic (administrative leadership) and emergent (adaptive leadership) functions of the organization” (Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007, p. 305). All levels of an organization can engage in this type of leadership, but its nature varies by hierarchical level and position.

CLT, then, is a framework for studying emergent leadership dynamics – via three types of leadership – as they relate to bureaucratic superstructures. It proposes that properly functioning CAS generate an adaptive capability for an organization while bureaucracy provides a coordinating and orienting structure. The central challenge of complexity leadership is to effectively manage the entanglement between the administrative and adaptive structures and behaviors, so as to ensure optimum organizational flexibility and effectiveness. For CLT, leadership solely exists in interaction and is a function of it; nonetheless, individual leaders can play a role in interacting with this dynamic, such as by enabling it.

Stacey, Griffin and Shaw (2000) offer a final, sixth framework, one they contend is different than existing complexity leadership frameworks. They point out a frequent internal contradiction within the complexity leadership science. They note that while most researchers focus on the dynamic interactions between agents, and the influence of relationships, their theories often collapse to being centered on the individual leader and his or her ability to influence interactions. Stacey (2007) builds upon this criticism with the contention that leadership theorists acknowledge the paradoxes generated by complexity theory, but then strive to dissolve them with a systems view of human organizations in which a rationally informed leader objectively observes the system and influences relationships (Panzar, 2009). In Stacey’s (Stacey, 2007, 2010; Stacey, et al., 2000) textbook-long framing of complexity leadership, he moves away from the notion of leadership as an individual agent that can control the evolution of a social system. He presents leadership as a “complex response process” that is based upon human interactions, realized through communicative acts, and grounded in the individual agent who has the freedom to choose amidst a context of enabling and constraining interactions (Panzar, 2009).

This section has reviewed the core concepts of and key frameworks that have been posited for complexity leadership. Nonetheless, it has only scratched the surface of the literature on complexity leadership. This field itself is an emergent dynamic, with new frameworks, insights, and practice guidelines being spawned regularly out of the interactions of the CAS that is complexity leadership science itself. In the following section I review some of the behavioral recommendations for positional leaders who want to apply complexity theory in their organizations.

Toward a Practice of Complexity Leadership

Various theories of complexity leadership have been in development for over a decade, resulting in, among other things, the frameworks noted above. There appear to be two general types of research on the behaviors required to engage in complexity leadership. In the first case, some researchers (e.g., Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001; Plowman & Duchon, 2008; Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007; Wheatley, 2006) have identified the principles of complexity sciences and then extrapolated leadership behaviors from them. The second variation consists of researchers (e.g., Goldstein, et al., 2010; Hazy, 2008; Lichtenstein & Plowman, 2009) who have longitudinally studied (sometimes retroactively) organizational and inter-organizational emergence phenomenon, using the lens of complexity leadership theory, and begun to validate the behaviors predicted by complexity leadership theory. There has been no longitudinal research done to date that I am aware of in which leaders intentionally applied complexity leadership theory to their organizations and overall organizational performance was monitored.[2]

After my review of literature on complexity leadership, there were three sets of practices that I feel are representative of the field to date. These are not meant to be a comprehensive distillation of complexity leadership behaviors, but rather a representative sampling. For further details, I refer readers to the book-length treatises on the topic (Goldstein, et al., 2010; Hazy, et al., 2007; McMillan, 2008; Stacey, 2007, 2010; Stacey, et al., 2000; Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2008; Wheatley, 2006). In the subsequent pages I describe those practices, and then offer a summary of recommendations for my personal practice.

The first of these sets of complexity leadership practices is from Marion and Uhl-Bien’s (2001) pioneering work in which they identify guidelines for leading in complex organizations. The second is from Plowman and Duchon’s (2008) research on dispelling the myths about traditional leadership – which they call “cybernetic leadership” – in service of the new, enabling behaviors of emergent leadership based upon complexity sciences. The final set of practice injunctions comes from Lichtenstein and Plowman’s (2009) work to construct a complex systems leadership theory of emergence at successive organizational levels.

There is some overlap amongst these sets of practices, as the authors are building upon each other’s work. However, I feel it is valuable to present each as a separate entity rather than attempt to consolidate them, as they each take a different perspective on complexity leadership. Marion and Uhl-Bien’s (2001) guidelines are more general in nature, for example, than Lichtenstein and Plowman’s (2009) emergent leadership behaviors, as the latter are specifically focused on actions that create the conditions for new emergent order. Plowman and Duchon’s (2008) approach, in contrast, focuses on traditional approaches to leadership and dispels the myths that arise from them through the application of complexity theory principles.

Guidelines for Leading in Complex Organizations (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001)

Complex leadership is the process of fostering conditions in which the new behaviors and direction of the organization emerge through regular, dynamic interaction. Rather than trying to control or exactly direct what happens within the organization, they influence organizational behavior through the management of networks and interactions. The following five practices underlie the execution of such leadership.

Foster network construction. Effective leaders learn to cultivate interdependencies through the management and development of networks within – and external to – their organization. This involves forging new connections where none exists, or enriching existing connections. The development of these networks provides contacts, but more importantly, they form the structure from which innovation can emerge. A strong network is a source of fitness for an organization, as it provides fitness to the technologies upon which it is based, as well as to the participating systems as well.

Catalyze bottom-up network construction. In addition to creating and maintaining networks, leaders also need to create the supportive environment in which new networks can emerge. By indirectly fostering network construction, they can catalyze network development. The ways to be such a catalyst range from delegation, resource allocation, and encouragement, to simply not interfering in network construction. Work environments can be reorganized to support interaction, additional decision-making powers and trust can be extended to their staff, and even new rituals and myths can be constructed that help create a culture of interaction and networking. Finally, complex leaders can also catalyze network development by avoiding solving problems for workers, insisting, rather, that they work out their own issues collaboratively.

Become leadership “tags.” A tag is the flag around which all parties rally, the binding philosophy that brings people together. Leaders can catalyze network development by becoming a tag. This does not mean that they control people with respect to a certain philosophy, but rather that they represent the essence of that philosophy or concept. For example, a school principle might serve as a tag for institutional excellence and the school’s reputation. These leaders rally people around the ideals of the organization, promoting an idea and an attitude.

Drop seeds of emergence. Complex leaders drop seeds of emergence by identifying, encouraging, empowering, and fostering connection between knowledge centers within an organization. Rather than trying to closely control, such leaders let people try new approaches, and pilot the application of novel ideas, then challenges them to evaluate and adjust their experiments. One way to do this is to send workers to conferences or other idea-generating environments in search of new insights and opportunities. The purpose here is to create a space of organized disorder, that spawns dynamic activity, emergent behavior, and creative surprises at multiple locations throughout the system.

Think systemically. Systemic thinking (Senge, 1990) is central to complexity leadership. It challenges leaders to continually be aware of the interactive dynamics at multiple levels of engagement, from aggregate, through meta-aggregate, to meta-meta-aggregate levels. This is not an easy thing to do, but it is vital to consistently see the broader pattern of events and understand the network of events that have caused a problem.

Emergent Leadership Dispelling Myths about Leadership (Plowman & Duchon, 2008)

Through the lens of conventional leadership, the world is assumed to be knowable and desired organizational futures are considered achievable through focused planning and the use of control mechanisms. Complexity scientists counter that uncertainty is a better starting point. Specifically, they contend that the world is not knowable, systems are not predictable, and living systems cannot be forced along a linear trajectory toward a predetermined future. There are four myths of conventional leadership that are therefore dispelled by the application of complexity sciences: leaders specify desired futures, leaders direct change, leaders eliminate disorder and the gap between intentions and reality; and leader influence others to enact desired futures. The behaviors of emergent leadership, based upon complexity science, which replace these “myths”, are summarized below.

Myth 1: Leaders specify desired futures. Conventional leadership worldviews frame leaders as visionaries, who see the future, chart the destination, and guide their organizations toward that destination. The repeated prescription is to: clarify the organization’s desired future, scan the external environment, design the requisite actions, and remove any obstacles. Complexity theorists suggest that organizational unpredictability often comes from within the organization, through the interactions of its members, which are not controlled by its leader. It is usually organizational members that develop the ideas that lead to productive futures for the organization, arguably a more important source of ideas than the vision of the leader at the top of an organization. Therefore, complex leaders should focus on enabling productive futures rather than controlling them (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). Thus, the “new reality” to replace Myth #1 is that “leaders provide linkages to emergent structures by enhancing connections among organizational members” (Plowman & Duchon, 2008, p. 139). This is based upon the complexity theory principle of emergent self-organization, in which the interaction of individual agents, exchange of information amongst them, and continuous adaptation of feedback from each other creates a new system level order.

Myth #2: Leaders direct change. Leadership theorists often contend that the essence of leadership is to lead change (e.g., Kotter, 1996). One of the principles of complexity theory concerns sensitivity to initial conditions. It notes that major, unpredictable consequences can arise out of small fluctuations in initial conditions (Kauffman, 1995). Thus small changes at anytime, anywhere in the system, can cascade and lead to massive change that may be inconsistent with the leader’s change vision. The new reality to replace this myth, then, is that “leaders try to make sense of patterns in small changes” (Plowman & Duchon, 2008, p. 141). By detecting and labeling patterns in the midst of emergent change, leaders have a greater chance of helping their organizations to respond effectively.

Myth #3: Leaders eliminate disorder and the gap between intentions and reality. Leaders are typically seen as needing to influence others to accomplish the tasks required to achieve organizational objectives. They are also expected to minimize conflict and cultivate harmonious relationships, such as in the case of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Complexity theorists contend that organizations are not characterized by stability and harmony, but rather exist on a continuum between stability and instability (Prigogine, 1997; Stacey, 1996). As organizations gravitate toward greater instability, due to destabilizing forces, new, emergent ideas and innovations arise. Therefore, rather than constantly attempting to stabilize an organization, leaders can at times help their organizations to benefit by being a source of disorder and destabilization. The new reality to replace Myth #3 is therefore: “leaders are destabilizers who encourage disequilibrium and disrupt existing patterns of behavior” (Plowman & Duchon, 2008, p. 142).

Myth #4: Leaders influence others to enact desired futures. The core of leadership is often considered to be influence. Two assumptions about influence run counter to a principle of complexity science. First, influence is often based upon the assumption that a leader knows what needs to be done and that the leader can subsequently influence those who need it to bring about a desired future state. These notions are, in turn, grounded in assumptions of linearity: that changes in one variable lead to anticipated changes in another. Complexity science, though, is based upon nonlinear interactions, in which multiple agents with varying agendas engage and influence each other’s actions. Nonlinear, living systems can learn, though. With such complexity and uncertainty within organizations, is it impossible for leaders to know and prescribe to others what to do. Instead, organizational members often help leaders to find directions out of confusion and uncertainty. As such, the new reality to replace Myth #4 is: “leaders encourage processes that enable emergent order” (Lichtenstein & Plowman, 2009, p. 143). An example would be for a leader to focus on clarifying processes rather than clarifying outcomes, and allow the organizational members to determine the relevant outcomes.

The Leadership of Emergence (Lichtenstein & Plowman, 2009)

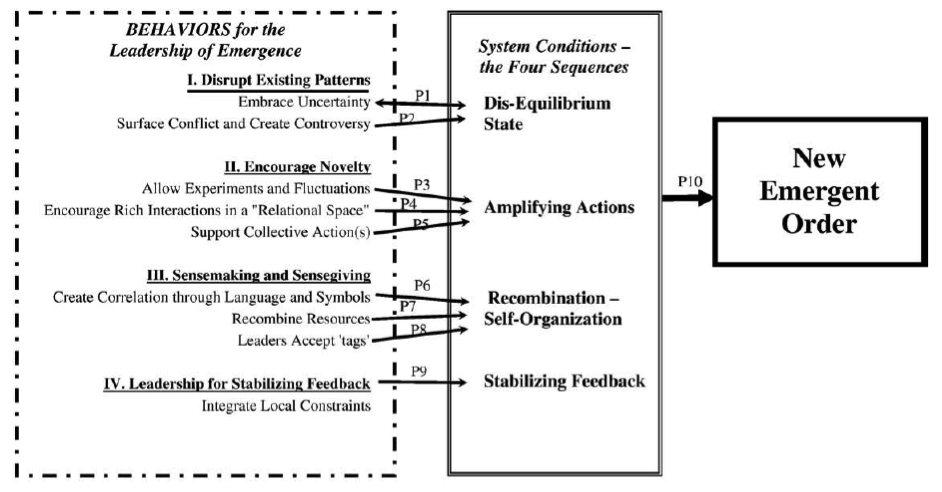

Lichtenstein and Plowman (2009) build upon both of the sets of behaviors discussed above (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001; Plowman & Duchon, 2008). Their focus is not on complexity leadership as a whole, but rather specifically on the production of newly emergent orders from the dynamic interactions between individuals. A newly emergent order arises when the capacity of a system to achieve its goals increases profoundly, by several orders of magnitude. The researchers identified four conditions for such emergence: the presence of a dis-equilibrium state, amplifying actions, recombination/”self-organization”, and stabilizing feedback. These conditions can be generated, they contend, through nine specific leadership behaviors, which are briefly discussed below. Figure 1 shows how these behaviors and conditions integrate to create a new emergent order.

Figure1. Behaviors that co-generate the conditions for the new emergent order. Reprinted from Lichtenstein and Plowman (2009, p. 621)

Disrupt existing patterns to generate dis-equilibrium. Two leadership behaviors contribute to this practice: embracing uncertainty and surfacing conflict to create controversy. Leaders and organizational members need to embrace uncertainty they face in order to initiate or heighten the system’s state of dis-equilibrium. By honestly assessing the situation, possible choices and uncertain outcomes, and not simply dictating solutions, leaders and members change the context in which they are operating, helping to destabilize the system. Additionally, generating constructive conflict and creating controversy are also key to driving a move toward dis-equilibrium, as this practice alters the conditions in which members function. In a space of discomfort and conflict, new ideas and possibilities tend to emerge.

Encourage novelty to amplify actions. Three behaviors serve to encourage novelty that in turn amplifies actions, helping small changes to cascade, escalate, and quickly move through the system. The first of these behaviors is to allow experiments and fluctuations, by letting seeds of potential change be dispersed widely and grow, leaders increase the chances that some will “take root” and spread rapidly through the system. The second leadership behavior is to encourage rich interactions through a culture of “relational space.” The non-linearity of complex adaptive systems can lead to rich and meaningful interactions that catalyze unexpected, positive outcomes. When done within a context of mutual trust, respect and psychological safety – a “relational space” – these rich interactions deepen the interpersonal connections amongst participants, thereby supporting the amplification of changes as they occur. The final leadership behavior is to support collective action. While certain individuals are responsible for key actions, often it is the collective action that creates the coherence and strength of an initiative, and allows for unexpected connections to arise. By allowing chaotic, collective action, leaders create the conditions for amplification of initial changes.

Sensemaking and sensegiving for recombination and self-organization. When systems are at their capacity limits, they either collapse or reorganize. As agents and resources in a system are recombined in new ways of interacting, system functioning tends to improve. By making and giving sense to issues within a complex adaptive system (through the following three behaviors), leaders support development of the conditions in which systems can recombine and self-organize. The first leadership behavior is to create correlation through language and symbols. Correlation means a shared understanding of a system (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). It can be created through specific, repeated language that reframes or gives additional meaning to a phenomenon, or via symbols that cultivate mutual understanding. Secondly, leaders can work to recombine resources. By uniquely recombining space, capital, capabilities and other vital resources, emergence can be fostered. These novel combinations alter the context in which people are working and stimulate new connections. Finally, leaders can accept “tags.” Tags were discussed above in the section on guidelines for leading in complex organizations (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). The researchers contend that when a single, or multiple, individuals accept becoming a “tag” for an emergence process, there is greater likelihood for recombination/”self-organization.”

Stabilizing feedback. Once amplification of change has begun, it sometimes needs to be dampened so that the emergent change does not spin the system out of control. The key behavior the researchers identified to enable this condition is to integrate local constraints. This means to make adjustments to the system based upon localized needs, thereby helping the emergent change to better adapt to that specific context. An example would be changing the hours of new operations of an organization to better meet an important group of constituent’s needs.

In sum, Lichtenstein and Plowman (2009) engaged in longitudinal research on three organizational and inter-organizational phenomenon that experienced emergence. They identified nine leadership behaviors that contributed to the development of four conditions vital for the emergence of new order. This set of practices builds upon previous work Plowman (2008) had done to dispel key myths of traditional leadership in the light of complexity sciences, as well as the ground-breaking insights of Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001) on complexity leadership in general. Multiple books (Goldstein, et al., 2010; Hazy, et al., 2007; McMillan, 2008; Stacey, 2007, 2010; Stacey, et al., 2000; Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2008; Wheatley, 2006), have extended these recommendations for practice, and are replete with examples. Nonetheless, I believe that the heart of complexity leadership in practice is represented in these three reviews.

As I venture forward as a leadership practitioner, based upon these readings, I have synthesized my understanding of what to do in practice in the following statement on complexity leadership.

A Memo to Myself on Practicing Complexity Leadership

Strive to create emergent conditions in the complex adaptive systems in which I engage and those which I serve. In such situations, the capacity of the system can dramatically increase, by orders of multiple magnitudes. The conditions for doing so include a state of dis-equilibrium, actions that amplify throughout the system, recombination or self-organization, and feedback that stabilizes the system from spinning out of control.

Strive to think systemically as much as possible, paying attention to multiple causal loops, the impact of small fluctuations, and consistently scanning for broad patterns at the micro, meso, and macro levels. To support emergence, there will need to be many networks – within and external to the organization. As such I can build them directly and support their development by others. I can plant seeds for emergence by strengthening knowledge centers within organizations and encouraging and enhancing the connections between those that are internal as well as with those that are external. Along the way, I need to be willing to become, or encourage a group of colleagues to become, a leadership “tag” – in which we represent the essence of a philosophy or concept central to the emergence process.

Remember that I don’t need to see the future and chart a linear path to get there. While I can create broad brush strokes for where we might consider going, my greatest impact will be in strengthening the connections among organizational members, thereby linking them to emergent structures. It is through them that most if not all of the innovations and novel ideas will arise. Therefore, my role is to enable productive futures, rather than controlling them, by enriching these connections. Rather than trying to direct change in a methodical manner, look instead to understand emerging patterns in small changes, so that I can feed that meaning-making into the learning, living system that makes up the organization I serve. These small changes can create unpredictable large scale impact, so my energy is better spent looking to identify them rather than trying to manage a linear change process over the long term. Thus, change leadership becomes more of an improvisational dance with the system, listening to how it is responding and adapting quickly in accordance.

Do not feel that I need to keep the organization and its systems in a state of constant harmony or equilibrium. Remember that innovative ideas and novel structures emerge not out of stability and balance, but from a state of dis-equilibrium and destabilization. Thus, be willing to allow for and even foster destabilization as I sense appropriate; go ahead and disrupt even healthy patterns of behavior if necessary. Don’t pretend that I know what to do and how to get there in a linear way. Remember that these are complex adaptive systems that operate with nonlinear behavior and therefore focus instead on strengthening and clarifying the processes that lead to emergent behavior rather than cutting down the obstacles in the way of the long-term vision.

Regularly encourage novelty, experimentation, pilots and prototypes. Small successes can become a form of positive deviance that rapidly scales across the system; the key is to create healthy conditions for those experiments to take place, trusting that the successes will emerge. Engage with others, and support the development of, “relational spaces” – arenas of deep trust, mutuality, respect and psychological safety in which the connections among members of the organization can be enriched and expanded. Use my abilities to see patterns and generate metaphors to help make and give sense to the phenomenon arising throughout this work. I can also use symbols to help create a mutual understanding. Above all, though, work to create this mutual understanding as it supports the process of self-organization when needed.

Remember that I will occasionally need to stabilize changes that are emerging, so that they don’t spin a system out of control. This can be done by adapting the change process and its effects such that they honor local constraints and are therefore more easily embedded within the local context. Above all, have fun, don’t get stuck in trying to logically figure this all out, and trust that within my network exist all of the resources required to support development of a newly emergent order in the systems I serve.

Two Limitations to the Practice of Complexity Leadership

This section briefly discusses two of the key limitations I see to the practice of complexity leadership: the need to supplement it with other epistemologies and leadership approaches; and no acknowledgement of the potentially insufficient capacity that people with conventional meaning-making systems may encounter in attempting to engage with it.

The Need for Other Perspectives to Enhance the Complexity Leadership Approach

While complexity leadership is maturing as a field unto itself, it is important to remember that it should be held in relationship to other leadership practices. In one of the first academic inquiries into complexity leadership, Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001) explicitly link complexity leadership to other trends that were emerging in the leadership literature (e.g., social capital, transformational leadership, self-leadership/empowerment, followership, and charismatic leadership). It is transformational leadership that holds the strongest link in their opinion. Bass (Bass & Avolio, 1990; Bass & Riggio, 2006), the leading scholar in transformational leadership agrees. In the Bass Handbook of Leadership (Bass & Bass, 2008), he describes complexity leadership as a field that “enlarges transformational leadership to include catalyzing organization from the bottom up through fostering of microdynamics of interaction among ensembles” (pp. 624-5). Thus, an individual should not venture into the realm of leadership with complexity leadership alone; other leadership theories and practices are likely needed to accomplish his or her objectives.

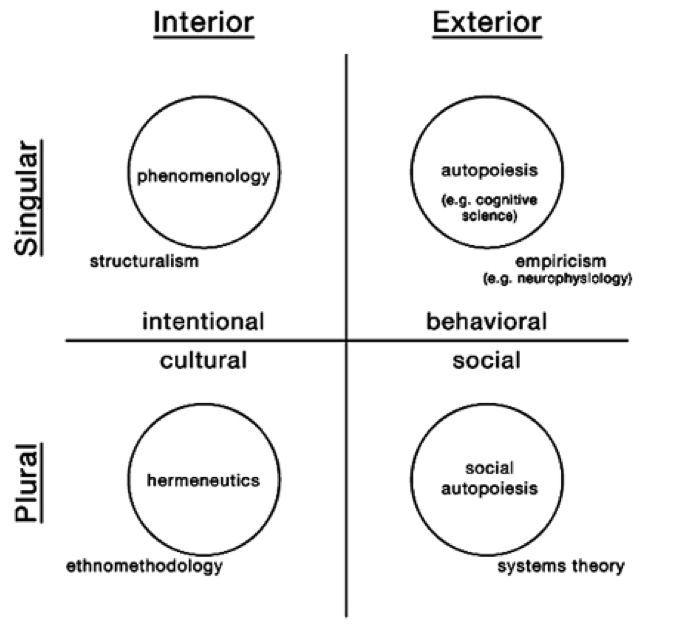

One way to frame the limitations of complexity leadership and the need to consider other leadership perspectives is to consider it within the context of integral methodological pluralism (IMP) (Wilber, 2006). A full explanation of IMP and its application is best left to other articles (e.g., Brown, 2010). Yet, essentially, IMP is a meta-epistemology that integrates all of the major epistemological methodologies. It is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The eight major methodologies of integral methodological pluralism Source: Wilber (2006). Courtesy Integral Institute.

Each of these methodologies enable us to reliably reveal knowledge about the different aspects of a phenomenon. These eight major methodologies help us to understand and explain the intentional, behavioral, cultural, and social forces that affect any given phenomenon, such as a leadership initiative. The more aware we are of all major forces at play, the greater chance we have of responding appropriately and succeeding in bringing about our objectives. The eight major methodologies are: phenomenology, structuralism, autopoiesis, empiricism, hermeneutics, ethnomethodology, social autopoiesis, and systems theory (Wilber, 2006). The usage of these terms here differs slightly from their use in other contexts.[3] The eight methodologies represent the main families of research methods available to scholar-practitioners. Certainly there are other research approaches, but these are some of the more historically significant (Wilber, 2003a). Each is a unique culture of inquiry which reveals a perspective and data that the others cannot. The practice of using as many of these methodologies as is practically possible, to gain a comprehensive understanding of any phenomena, is called integral methodological pluralism (Wilber, 2006).

Complexity theory is based in two of the eight methodologies of IMP: it is mostly grounded in systems theory (Bertalanffy, 1968; Laszlo, 1972a, 1972b) and somewhat draws upon social autopoiesis (Capra, 1996, 2002; Luhmann, 1984, 1990). Complexity theory has been explained as an expansion of systems theory by some leading researchers (Stacey, et al., 2000). Thus, while it can offer very powerful insights about leadership, it still holds an epistemological bias that filters out other equally valid data concerning leadership. As such, the practice of complexity leadership should be supplemented with other types of leadership that draw upon different epistemologies, thereby helping leaders to see a broader picture than that offered by complexity leadership alone.

Uhl-Bien and Marion (2007) strive to do this in their article on complexity leadership theory. Not only did they mention the linkages to transformational leadership and other leadership approaches in their earlier writings, their framework for complexity leadership includes adaptive leadership, administrative leadership, and enabling leadership. In my opinion, this is primarily done to acknowledge that not all leadership activities require or are served by a complexity leadership approach. In some cases, such an approach is unnecessarily complex and not useful when traditional managerial and leadership practices are sufficient (such as in administrative leadership). Thus, when combined with transformational leadership and even other leadership practices, a leader begins to draw upon multiple epistemologies that enable him or her to see a more comprehensive picture.

However, it should be noted that even this combination – complexity leadership theory plus transformational leadership theory and adaptive, administrative, and enabling leadership – will still leave out several of the key epistemologies that provide important data on any leadership situation. Missing but often highly relevant perspectives include phenomenology (Idhe, 1986), hermeneutics (Howard, 1982), ethnomethodology (e.g., cultural anthropology, ethnography, discourse analysis), and psychological structuralism (Kegan, 1982, 1994; Kohlberg, 1981, 1984; Loevinger, 1976).

In my review of the complexity leadership literature, particularly salient for me was how strongly it de-centers the subject.[4] The complexity sciences upon which this field is based are grounded in objective, third-person epistemologies such as empiricism and systems theory. These perspectives, as traditionally defined, do not incorporate the subjective viewpoint of the observer or participant. This appears to be a profound limitation for the complexity leadership literature because it does not acknowledge, much less attempt to tap into as a source for creative insight, the subjective reality and internal experience of leaders themselves. Humans are not merely rational, objective beings, and, as such, subjective forces, dynamics and influences are present during any leadership moment. To not even acknowledge the entire subjective reality experienced by leaders and draw upon it as part of the complexity leadership process seems to be doing a disservice to both the field and the leaders that engage with it. A complexity leadership theorist might say that such subjective experiences and influences are indeed incorporated into the approach as they are considered as potential small perturbations to the complex adaptive system that can cause large-scale change. However, this response still demonstrates an objectification of subjectivity, for which empiricism has long been criticized.

Fundamentally, despite the critical viewpoint I have offered, I believe that efforts to encourage complexity leadership to incorporate the subjective sciences and other epistemologies are not likely succeed. Such a strategy seems short sighted. Rather, complexity leadership should be embraced for the valuable perspectives it provides and encouraged to develop its approaches to leading through that epistemology. Yet it should also be held within a larger context and broader leadership approach that incorporates other types of epistemological inquiry. What we need is not to force different epistemologies and leadership approaches to change so as to be inclusive of all others, but instead to adapt a meta-epistemological framework – and ultimately a meta-leadership framework – that embraces each of them for their unique perspective while also recognizing their inherent limits. Integral methodological pluralism offers one such meta-epistemological framework, and a leadership framework based upon it may offer a pathway through this theoretical entanglement.

Meaning-Making Systems and Complexity Leadership

The second potential limitation I see to complexity leadership concerns the degree of meaning-making maturity that may be required to effectively engage with it. My proposition is that leaders with more mature meaning-making systems may be more capable of engaging the practices of complexity leadership. Conversely, those with conventional meaning-making systems may not be able to fully adapt to the fundamental changes in leadership perspective called for by complexity leadership.

Complexity leadership calls for a letting go of the notion of control and “knowing what to do,” acknowledgement that the future cannot be predicted, and a recognition that organizations and groups are not able to move in a linear path toward a pre-defined objective. Traditional leadership is largely decentralized in this approach, and those with positional power are asked to think in systems, tend to the conditions that support emergence, and focus on process rather than outcome. The literature challenges leaders to manage the polarity between equilibrium and dis-equilibrium – between stability and chaos – and that they foster conflict and dissonance in the system regularly. Complexity leaders are also called to see multiple causal loops, recognize patterns within complex processes from the micro to the macro, and engage in improvisational dance with complex adaptive systems – listening closely and responding in an instant. Finally, they also need to remember to stabilize things when too much emergence occurs too fast so the entire system does not gyrate out of control (Lichtenstein & Plowman, 2009; Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2008).

These leadership behaviors would seem to require not only considerable cognitive complexity, but also a very mature self-identity and ability to make meaning. The meaning-making systems of the majority of managers and leaders may not be sufficient to sustainably engage – without regular support – in these behaviors. To clarify this point, I offer below a brief review of the studies that have estimated the distribution of leaders and managers across the spectrum of meaning-making systems, from pre-conventional to conventional to post-conventional.

The constructive-developmental frameworks of Kegan (1982, 1994) and Loevinger/Torbert (Loevinger, 1966, 1976; Merron, Fisher, & Torbert, 1987; Torbert, et al., 2004) have most frequently been used to study the intersection of leadership and meaning-making. In a large-scale (n = 535) study of managers and consultants in the UK (Cook-Greuter, 2005), approximately 43% held a post-conventional stage of meaning making. These are the most mature stages [Individualist, Strategist, Alchemist and Unitary/Ironist in Torbert’s action logics framework (Torbert, et al., 2004)]. In a study (n = 497) of US managers and supervisors (consultants not included), only 7% were assessed with post-conventional meaning-making, and in the general adult US population (n = 4510), about 18% have developed to this level of maturity (Cook-Greuter, 2004, 2005). Rooke and Torbert (2005), drawing upon some of the same data sets, claim that 15% of leaders hold these post-conventional stages. While there is no precise data available on this topic, it is fair to say that a large majority (65-85%) of leaders and managers in developed countries hold a conventional meaning-making system.[5]

I propose that the qualities of conventional meaning-making systems limit the ability of those with them to engage effectively in complexity leadership. This is because complexity leadership seems to require a strong comfort with ambiguity, uncertainty, and not knowing. Other requirements seem to be: enter deeply into multiple frames of reference and take many perspectives [such as to manage the entanglement between adaptive and administrative structures (Uhl-Bien, et al., 2007)] ; recognize mutual causality in human interactions; deal with conflicting needs and duties; and consciously allow others to make mistakes. Research suggests that these qualities arise with the development of postconventional meaning-making (Cook-Greuter, 1999, 2000; Joiner & Josephs, 2007; Nicolaides, 2008).

Thus, those with later stages of meaning-making may be able to adeptly handle the challenges of complexity leadership. Leaders with a conventional stage of meaning-making (Diplomats, Experts, Achievers in Torbert’s action logics framework) would seem to have less of a chance of being successful. This is because, for example, the main focus of the expert action logic is expertise, procedure and efficiency (Cook-Greuter, 2004). Experts tend to be immersed in the logic of their own craft and regard it as the only valid way of thinking. They are often reactive problem solvers and make decisions based on incontrovertible “facts” (Joiner & Josephs, 2007). These qualities of the Expert meaning-making system do not seem to align with the demands of complexity leadership. Achievers face a similar struggle, although they may have better chances. For them, the main focus is on delivery of results, effectiveness, achieving goals and being successful within the system (Cook-Greuter, 2004). They tend to emphasize reason, analysis, measurement and prediction (Cook-Greuter, 1999). It is not until the first of the postconventional action logics – the Individualist – that one really begins to understand complexity, systemic connections and unintended effects of actions. Additionally, Individualists can play different roles in varying contexts and are able to adjust their behavior to the context (Torbert, et al., 2004). These qualities, and the others previously mentioned that develop in the postconventional action logics, seem to more accurately fit the needs of complexity leadership.

In sum, while complexity leadership theory and its various approaches offer considerable potential improving leadership, the training of it should probably be reserved for leaders who have demonstrated advanced (i.e., postconventional) meaning-making capacity. It does not seem realistic to expect leaders with a conventional action logic to learn and sustainably engage with it over an extended duration.

Conclusions

The application of complexity theory to leadership has generated a novel field and important perspective that facilitates the understanding of complex organizational behavior. It reveals dynamics and forces present within and across organizations that no other approach to leadership offers. When combined with other leadership approaches that complement its epistemological bias toward systems theory, complexity leadership can be a powerful tool for any individual to support organizational change.

For me, personally, the study of complexity leadership theory and practice has provided a fresh and powerful leadership lens. My engagement with this literature has dislodged several notions I previously held about leadership and has inspired new ways to think about and act in the face of complexity. My biggest change is a commitment toward supporting the conditions for the emergence of novel order within complex adaptive systems. By focusing on creating fertile ground for innovation and insight to sprout within and across systems, I feel that I do have some degree of influence over the otherwise uncontrollable reality of organizational behavior.

The field of complexity leadership theory and practice is still young and will require considerable research to substantiate its claims and realize its full potential. Complexity leadership is not a panacea for our leadership problems, and never will be in my opinion. No matter how much research backs its findings, it will continue to require supplemental perspectives to fully map the leadership terrain. Nonetheless, I feel that it offers one of the most important ways to reflect upon and engage in leadership. Our organizational environments are becoming increasingly complex, and the complexity leadership approach is grounded in decades of research in how to work with complex systems. Fundamentally, its insights and guidelines provides me with additional hope and inspiration that we will, collectively, learn how to handle the global social, economic, and environmental challenges that symbolize today’s world.

References

Anderson, Philip (1999). Complexity theory and organization science. Organization Science, 10(3), 216.

Bak, Per, & Tang, Chao (1989). Self-Organized Criticality. Physics Today, 42(1), S27.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). Implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Passmore (Eds.), Research in Organizational Change and Development (pp. 231-272). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig von (1968). General systems theory. New York: Braziller.

Brown, Barrett C. (2010). Use of integral methodological pluralism to comprehensively engage in sustainability initiatives. Unpublished manuscript. Fielding Graduate University.

Capra, Fritjof (1996). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. New York: Anchor Books.

Capra, Fritjof (2002). The hidden connections: Integrating the biological, cognitive, and social dimensions of life into a science of sustainability. New York: Doubleday.

Carley, K., & Hill, V. (2001). Structural change and learning within organizations. In A. Lomi & E. R. Larsen (Eds.), Dynamics of organizational societies (pp. 63-92). Cambridge, MA: AAAI/MIT Press.

Carley, K., & Lee, J. S. (1998). Dynamic organizations: Organizational adaptation in a changing environment. Advances in strategic management: A research annual, 15, 269-297.

Cilliers, P. (1998). Complexity and postmodernism: Understanding complex systems. London: Routledge.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement. Dissertation Abstracts International, 60 06B(UMI No. 993312),

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2000). Mature ego development: A gateway to ego transcendence? Journal of Adult Development, 7(4).

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2004). Making the case for a developmental perspective. Industrial and Commercial Training, 36(6/7), 275.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2005). Ego development: Nine levels of increasing embrace. Unpublished manuscript.

Coveney, P. (2003). Self-organization and complexity: A new age for theory, computation and experiment. Paper presented at the Nobel symposium on self-organization at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Goldstein, J. A. (1995). Using the concept of self-organization to understand social system change: strengths and limitations. In A. Albert (Ed.), Chaos and society (pp. 49-62). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Goldstein, J. A. (2008). Conceptual foundations of complexity science: Development and main constructs. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations (pp. 17-48). Charlotte, NC: IAP – Information Age Publishing Inc.

Goldstein, J. A., Hazy, J. K., & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2010). Complexity and the nexus of leadership: Leveraging nonlinear science to create ecologies of innovation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goleman, Daniel (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Goodwin, B. (1994). How the leopard changed its spots: The evolution of complexity. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219-247.

Halal, W. E., & Taylor, K. B. (Eds.). (1999). Twenty-first century economics: Perspectives of socioeconomics for a changing world. New York: Macmillan.

Hazy, J. K. (2005). A leadership and capabilities framework for organizational change: Simulating the emergence of leadership as an organizational meta-capability. Unpublished Ed.D., The George Washington University, United States — District of Columbia.

Hazy, J. K. (2006). Measuring leadership effectiveness in complex socio-technical systems. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 8(3), 58-77.

Hazy, J. K. (2007). Parsing the “influential increment” in the language of complexity: Uncovering the systemic mechanisms of leadership influence. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Conference.

Hazy, J. K. (2008). Patterns of leadership: A case study of influence signaling in an entrepreneurial firm. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations (pp. 379-415). Charlotte, NC: IAP – Information Age Publishing Inc.

Hazy, J. K., Goldstein, J. A., & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2007). Complex systems leadership theory: New perspectives from complexity science on social and organizational effectiveness. Mansfield, MA: ISCE Pub.

Hëdstrom, P., & Swedberg, R. (1998). Social mechanisms: An analytical approach to social theory. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Heifetz, Ronald A., Grashow, Alexander, & Linsky, Martin (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Press.

Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden order. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Howard, Roy J. (1982). Three faces of hermeneutics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Idhe, Don (1986). Experimental phenomenology: An introduction. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Joiner, B., & Josephs, S. (2007). Leadership agility: Five levels of mastery for anticipating and initiating change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kan, Chen, & Bak, Per (1991). Self-Organized Criticality. Scientific American, 264(1), 46.

Kauffman, S. A. (1995). At home in the universe:Tthe search for laws of self-organization and complexity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kegan, Robert (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, Robert (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kohlberg, Lawrence (1981). The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Kohlberg, Lawrence (1984). The psychology of moral development: The nature and validity of moral stages. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Kotter, John P. (1996). Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Langston, C. G. (1986). Studying artificial life with cellular automata. Physica, 22D, 120-149.

Laszlo, Ervin (1972a). Introduction to systems philosophy: Toward a new paradigm of contemporary thought. New York: Gordon and Breach.

Laszlo, Ervin (1972b). The systems view of the world: The natural philosophy of the new developments in the sciences. New York: Braziller.

Levy, S. (1992). Artificial life: The quest for new creation. New York: Random House.

Lewin, R., & Regine, B. (2003). The core of adaptive organizations. In E. Mitleton-Kelly (Ed.), Complex systems and evolutionary perspectives on organizations: The application of Complexity Theory to organizations (pp. 167-184). London: Pergamon.

Lichtenstein, B. B., & Plowman, D. (2009). The leadership of emergence: A complex systems leadership theory of emergence at successive organizational levels. Leadership Quarterly, 20(4), 617.

Lichtenstein, B. B., Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., Seers, A., Orton, J. D., & Schreiber, C. (2006). Complexity leadership theory: An interactive perspective on leading in complex adaptive systems. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 8(4).

Loevinger, J. (1966). The meaning and measurement of ego-development. American Psychologist, 21, 195-206.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: conceptions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Luhmann, Niklas (1984). Social systems (J. Bednarz & D. Baecker, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Writing Science, Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, Niklas (1990). Essays on self-reference. New York: Columbia University Press.

MacIntosh, R., & MacLean, D. (1999). Conditioned emergence: A dissipative structures approach to transformation. Strategic Management Journal, 20(4), 297.

Marion, R. (1999). The edge of organization: Chaos and complexity theories of formal social systems. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Marion, R. (2008). Complexity theory for organization and organizational leadership. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations (pp. 1-15). Charlotte, NC: IAP – Information Age Publishing Inc.

Marion, R., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2001). Leadership in complex organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4), 389.

McKelvey, B. (1997). Quasi-natural organization science. Organization Science, 8(4), 352-380.

McKelvey, B. (2008). Emergent strategy via complexity leadership: Using complexity science and adaptive tension to build distributed intelligence. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations (pp. 225-268). Charlotte, NC: IAP – Information Age Publishing Inc.

McMillan, Elizabeth M. (2008). Complexity, management and the dynamics of change: Challenges for practice. London; New York: Routledge.

Merron, K., Fisher, D., & Torbert, W. R. (1987). Meaning making and management action. Group & Organization Studies, 12(3), 274.

Nicolaides, A. (2008). Learning their way through ambiguity: Explorations of how nine developmentally mature adults make sense of ambiguity. Unpublished Ed.D., Teachers College, Columbia University, United States — New York.

Nowak, M. A. , May, R. M., & Sigmund, K. (1995). The arithmetics of mutual help. Scientific American, 272(6), 76-81.

Panzar, C. (2009). Organizational response to complexity: Integrative leadership. A computer simulation of leadership of inter-dependent task-oriented teams. Unpublished Ed.D., The George Washington University, United States — District of Columbia.

Plowman, D. A., & Duchon, D. (2008). Dispelling the myths about leadership: From cybernetics to emergence. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations (pp. 129-154). Charlotte, NC: IAP – Information Age Publishing Inc.

Prigogine, I. (1997). The end of certainty: Time, chaos, and the new laws of nature. New York: Free Press.

Prusak, L. (1996). The knowledge advantage. Strategy & Leadership, 24, 6-8.

Rooke, D., & Torbert, W. R. (2005). Seven transformations of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 83, 66.

Senge, Peter M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review (November).

Stacey, R. D. (1996). Complexity and creativity in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Stacey, R. D. (2007). Strategic management and organisational dynamics: The challenge of complexity (5th ed.). Harlow, England; New York: Prentice Hall/Financial Times.

Stacey, R. D. (2010). Complexity and organizational reality: Uncertainty and the need to rethink management after the collapse of investment capitalism. London; New York: Routledge.

Stacey, R. D., Griffm, D., & Shaw, P. (2000). Complexity and management: Fad or radical challenge to systems thinking? London: Routledge.

Surie, G., & Hazy, J. K. (2006). Generative Leadership: Nurturing innovation in complex systems. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 8(4), 13-26.