Elizabeth F. Turesky, Kristen S. Cloutier and Marisa F. Turesky

Abstract

The authors address the dynamic interaction between culture and gendered leadership perceptions. Using Hofstede’s cultural framework of the masculinity/femininity dimension, this study explores the ways fourteen Italian women have achieved and sustained successful leadership positions in Italy and then evaluates how Italy’s dimension of masculinity/femininity affects women’s opportunities as emerging leaders. Finally, the authors conclude with suggestions for managers in Italy, which can be applied to other masculine countries, to provide greater opportunities for women to realize their leadership potential in their society.

Introduction

Researchers agree that gender roles are both learned and culturally defined. They have demonstrated that gender specific roles are instilled at an early age for males and females and are attributed to different “norms, characteristics, values and behaviors for both sexes” (Maddock and Parkin, 1993). As the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir (1993) said, “One is not born a woman, one becomes one.”(p. 281). We assert that cultural expectations and gendered stereotypes play a vital role in the creation of women’s perceptions of leadership; that management is “culturally dependent” (Hofstede, 1983) and that national culture limits the variation of cultural norms in organizations. Supporting and furthering these theories, empirical and non-empirical studies provide support for the idea that national culture, a common identity shared by members of a specific nation, affects the perception and role of leadership in organizational cultures (Li, 2001; House, Wright & Aditya, 1997; Dorfman, 1996; Gerstner & Day, 1994).

This study focuses on the relationships between gender, leadership and cultural norms affecting pathways to leadership among fourteen Italian woman leaders in Italy. Using social psychologist and organizational anthropologist Geert Hofstede’s (1980) landmark study and resulting cultural framework of the masculinity/femininity dimension, the authors sought to explore the relationship among Italian culture, gender and leadership roles as they relate to enabling factors and challenges posed for women in their emerging leadership roles. From ancient time, Italy has been the symbol of creativity, superb taste and exquisite culture, producing some of the greatest painters, sculptors, poets, musicians, fashion designers, composers, mathematicians, philosophers and architects of all times– who produced the original facets of Western Civilization. How is it that in such a culturally innovative country, the ranking in the Global Gender Gap Report worsened Italy’s ranking in the world rather than improved it?

There is a striking absence of women in positions of leadership in Italian politics and corporations. The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) October 2010 Global Gender Gap Report studied such issues as wage parity, labor-force participation, and career-advancement opportunities for women, arguing that closing the gender gap Europe-wide could boost the euro zone’s GDP as much as 13 %. In every category but education, Italy lags placing 97th in opportunity for women to take leadership positions. According to the WEF, Italy dropped from its 2009 ranking of 72 to 74 out of 134 countries. Nordic countries were at the top, the United States at 19, France at 46. China at 61 had one of the smallest number of women elected to parliament among the advanced industrial countries. In addition, except for a few cases in the minor Italian parties, there have never been female party leaders. Italy has never had a woman head of state or prime minister and very few women have held cabinet positions. When women have held cabinet positions, they are in posts for which their gender is assumed to make them more suitable, such as family and education. The number of prominent women in Italian politics is extremely small. (Campus, 2010) It is of great interest to the researchers to understand this phenomenon in this richly cultural and beautiful country. What distinctive challenges do Italian women face on their pathways to becoming leaders? What are cultural and personal factors that hinder or enable Italian women to develop their leadership potential?

In seeking to understand a nation’s leadership culture, gender norms and stereotypes come into play particularly when it comes to considering women as leaders. Simply put, the ways women think about leadership are influenced by the norms of the society and the culture in which they lead. This is particularly evident in countries such as Italy, where society’s distinctively masculine culture impacts the pathways for women as leaders.

Gender Roles within Cultures

Culture shapes and is shaped by social beliefs, values and norms about the appropriate division of gender roles. In this way, gender is a social and cultural construction. Thus, boys and girls are socialized differently by the traditional societal mores that reflect the beliefs of that society (Arrindell et al., 2004). As such, different expectations exist for males and females, and from birth onward a social sex role curriculum is prescribed. Both women and men adopt these gendered belief systems as part of socialization into their culture (Inglehart & Norris, 2003). Families, schools, universities, and societies are all cultural products and instruments of enculturation. Socialization processes are culturally constructed with differing social roles prescribed to men and women across nationalities (Hofstede, Arrindell, Best, De Mooij, Hoppe, & Van de Vliert, 1998).

Cultural patterns, such as social background, education, career choice, family, children, and the distribution of housework, ascribed to men and women affect the composition of gender in leadership positions (Sczesny, Bosak, Neff, & Schyns, 2004; Hojgaard, 2002). Li (2001) claims that it is this “collective programming” that determines the perceptions of individuals within a specific culture, and thus the definition of leadership within that culture. It is self-fulfilling: a country’s leaders and followers are prescribed the same societal norms and therefore reinforce each other’s expectations and behaviors, creating the organizations and institutions that perpetuate these very norms (Hofstede, et al.,1998).

The larger and seemingly endless debate in which our study finds itself is whether culture shapes leadership or vice versa. As such, the dichotomy is an artificial one where the two will feed into and influence one another in a reciprocal interaction that continues to unfold over time. Hofstede (2001, p. 388) writes, “Asking people to describe the qualities of a good leader is in fact another way of asking them to describe their culture.” In other words, a nation’s culture is reflected in an individual’s perceptions of leadership (Inkeles and Levinson, 1969). At the same time, those same individuals working in an organization shape the organizational culture in which they work (Ferraro, 1990; Frost, 1985; Gregory, 1983; Hofstede, 1997; Schein, 1985). Shaw (1990), for example, showed that individuals from different cultures list different attributes for what they perceive as “leadership”. Gerstner and Day (1994) studied perceptions of leadership among students from eight different countries. Perceptions about leadership traits differed significantly among the representatives of the various countries. However, the researchers found no significant differences in leadership perceptions within each country in testing for the gender variable.

Other research has shown that women’s beliefs regarding gender and perceptions about leadership can be directly attributed to the opportunities available in each respective culture (Eagly, 1987; Sczesny, Bosak, Neff, & Schyns, 2004). Both men and women perceive themselves as leaders based upon the cultural perceptions about what traits constitute leadership. Several studies have found that characteristics typically ascribed to leaders correspond much more to traits described as male rather than female (Wood & Eagly, 2002; Sczesny, et al. 2004; Aaltio & Mills, 2002). When Sczesny, et al. (2004) researched leadership characteristics through cross-national comparisons— comparing Australia, Germany, and India—they discovered that the impact of gender roles and stereotypes on the perception of leadership could be observed. Wood & Eagly (2002) observed that men’s political and economic power in patriarchal social structures is perpetuated through male privileges that are incorporated into family structures, organizational practices, and political processes. These varied influences make it more difficult for women to move into positions of power and influence. However, when women are perceived as being as competent as men, they are also seen as violating the gender role norms that require women to be more communal than men. In other words, leader roles that are culturally masculine are incompatible with people’s expectations about women, which therefore creates a challenge to women leaders (Eagly & Carli, 2007; Eagly, 1987).

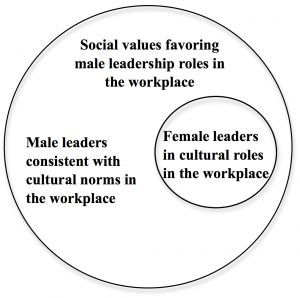

Although distant and recent history offers numerous examples of women who managed to circumvent the prevailing cultural norms or their societies to pursue careers that were prohibited to them, these notable women leaders constitute exceptions rather than the norm. Societal norms regarding appropriate roles for females and males affect their career choices and success (Heilman, et al., 2004; Stroh, Brett, & Reilly, 1992; Walker & Fennell, 1986) As Figure 1 illustrates, perceptions about leadership are expressions rooted in culture (Frost, 1985; Meindl, 1995; Lord and Maher, 1993; Schein, 1985) with women leaders attempting to assimilate in their counter cultural roles and experiencing the consequences of being part of a marginalized subculture.

The literature is replete with examples across the globe of the perpetuation of marginalizing women as leaders. Hovden (2000) found that the organizational culture of Norwegian sporting organizations allows those in power (men) to select individuals with similar interests, goals, and perceptions (other men) for advantaged positions. In a study of the South African educational administration, Chisholm (2001) found that the male dominant leadership in educational administration was linked to the gendered character of organizational culture and the way in which women have negotiated or failed to negotiate these conditions. In a study of school principalship in Israel, Addi-Raccah (2005) found that organizational culture, which is made up of shared beliefs, values and norms, could affect recruitment practices, thus either lowering inequality or fostering it. Research in cross-cultural comparisons indicated that the impact of gender stereotypes on the perception of leadership could also be observed in different countries: in Germany, the United Kingdom (Schein & Mueller, 1992), China, and Japan (Schein, Mueller, Lituchy, & Liu, 1996).

In her 2004 study of a local women’s association in Japan, Tsunematsu found that women’s associations in Japan – number one on Hofstedes’s Masculinity Index (95) — represent a place for women to exhibit power in the public sphere in ways that men cannot easily imitate. These associations “challenge the dichotomous power relations between men and women in the contrast of the public and the domestic” (Tsunematsu, 2004, p. 105). These and other studies (Rodman, 1972; Lipman-Blumen, 1984; Smits, Mulder & Hooimmeijer, 2003) illustrate that beliefs about gender roles and power are embedded in the core beliefs of the community.

The important implication of this is that for female community members to change their lives, and therefore their access to leadership positions, they must challenge the cultural implications of their gender. To go against a hegemonic system of values surrounding an entire demographic is to challenge the engrained ideology. For example, because Japanese women have traditionally defined themselves as mothers and wives in response to cultural influences, members of the women’s associations are constantly under pressure to adhere to the appropriate behavioral code ascribed by gender, regardless of the stance of official social propaganda regarding equality. Women who do not adhere to these unwritten rules are likely to be criticized (Kawahara, 2007; Goodman, 2002).

Ecklund’s (2006) study of organizational culture and women’s leadership in six Catholic parishes in the United States demonstrated that traditional and progressive parish cultures differed dramatically. The study showed that female leadership can influence dominant cultural beliefs and perceptions about the role of women in organizations. Traditional parish cultures allow women to fill leadership positions temporarily, but only until men are found to fill the positions permanently. In progressive parish cultures, in contrast, women are allowed and encouraged to fill leadership positions as part of a larger commitment to equality for all people. In addition, women’s leadership in traditional parishes was seen as a result of the priest shortage, and these women were given relatively little power and responsibility. Women who held leadership positions in progressive parishes, on the other hand, were invited to serve on the pastoral and finance councils and actively influenced the way their parishes viewed the role of women.

Nonetheless, Datta and McIlwaine’s (2000) research shows that it is extremely difficult to change hegemonic gender roles. Nationally held cultural attitudes toward gender roles influence perceptions of leadership and workplace roles that women choose. Our review of the literature is clear: cultural factors play a critical role in the creation of an individual’s perceptions of leadership characteristics and roles (Ozkanl and White, 2008). This is true cross culturally and around the globe.

Imposed Cultural Change

A 2010 study by research firm Gea-Consulenti Associati (Bellavigna & Zavanella, 2010) showed that women occupied about 7 % of Italy’s corporate management positions, compared with an average of 30-35 % in other developed nations. (Martinuzzi & Krause-Jackson, 2010). According to the study, women held 809 of the 11,730 management jobs at the 1,800 surveyed companies in 2010. In Italy’s government leadership positions, women occupy 21.3 % of the Lower House of Parliament and 18.4% of the Upper House (Inter-Parliamentary Unit-IPU, 2010). Italy’s statistics are higher than the European average in the lower house (19.7%), but much lower than the European average in the upper house (21.9%) (IPU, 2011). This compares with the highest percentages in Belgium, which has 39.3% of women in the Lower House and 36.6% in the Upper House (IPU, 2011).

Today, Norway is leading the way as the only European country with a rate of over 40% women in top jobs and as board members in public companies thanks to government intervention with a gender representation law passed in 2004. By doing so, Norway was the first country in the world to demand that a greater balance in percentage of women be represented within the boards of public limited companies. Interestingly, an agreement was reached between government and the private business sector, allowing for suspension of these rules if the desired gender representation was achieved voluntarily by 1 July 2005. They were not. A survey carried out by Statistics Norway showed that by 1 July 2005, only 13.1 % of these companies fulfilled all the demands required by the law, and only 16 % of the board members were women. Because of government intervention, impressive gains were achieved in gender equality in less than four years. By 2008, approximately 40 % of the board members in public companies were women, and 93 % of the public limited companies fulfilled the requirements of representation of both sexes laid down in the Public Limited Companies Act. These gains have been sustained to date.

The statistics on government interventions through law in the representation of women in public and private institutions bring us to the discussion of quotas to stimulate organizational change. In recent years, more than a hundred countries have instituted quotas to enlist female candidates into running for political office (Krook, 2006). Scandinavian countries such as Denmark and Sweden first introduced quota provisions in the 1980s (Dahlerup & Freidenvall, 2005). Krook (2006) suggests that international norms and transnational information sharing help shape national quota debates, yet Italy did not begin instituting party and legislative quotas until the 1990s (Krook, 2006). Traditional attitudes towards women, along with the de facto division of gender roles, have been identified as contributing barriers to women’s advancement, including women’s advancement as political leaders.

Italy’s inertia to female equality seems to have been enhanced by its current political leadership. Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s behavior, his statements and the articles found in media controlled by him portray women as ill-suited for meaningful leadership positions (Nadeau, 2010). One of many examples of Berlusconi’s insensitive statements was his explanation for his government’s inability to combat Italy’s growing number of rapes: “We don’t have enough soldiers to stop rape because our women are so beautiful” (p.2). The combined effect of a masculine culture, Berlusconi’s actions and statements, media support for those actions and statements and official insensitivity if not hostility to women, “has made the workplace an unwelcoming if not downright hostile environment for women with even moderately serious ambitions” (p.2).

Cultural explanations are similarly a plausible reason why the Scandinavian countries have made such strides in women’s political participation (Yeganeh & May, 2011). Another explanation is the difference in the role of government intervention in determining consequences for noncompliance. In Norway, by January 2008, 77 public limited companies had failed to comply with the gender representation rules. These companies received a letter from the Brønnøysund Register Centre, giving them 4 weeks notice to comply with the rules. Companies that fail to fulfill the demands within the time limit are given notice and subjected to adverse public disclosure. The companies are then given a second 4 weeks notice to comply with the rules. Failure to do so leads the court to a suit seeking dissolution of the firm.

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Cultures

In order to better understand the data being presented in this current study, we begin with a brief overview of the dimensions of national cultures studied by Hofstede, and more specifically, the dimension of masculinity/femininity. Hofstede’s cultural model provides a useful framework for understanding the pervasive societal challenges Italian women face in their leadership development and their potentially significant contributions to Italy.

Geert Hofstede examined a large body of survey data collected in the 1960s and early 1970s about the values of a sample of IBM employees in over 40 countries (Hofstede, 1980). The individuals that Hofstede studied were workers in the local subsidiaries of IBM, a multinational corporation. From one country to another, these individuals represented almost perfectly matched samples and were similar in all respects except nationality (Hofstede, 1980). Additional data were collected in the early 1970s that replicated the original findings pointing to the persistence of the dimensions across time. The survey itself contains questions related to 14 “work goals” such as earnings, challenge, cooperation, and employment security. Respondents were asked to consider these work goals and then, “Try to think of…which would be important to you in an ideal job; disregard the extent to which they are contained in your present job. How important is (each work goal)” (Hofstede, 2001, p.256). Respondents rated each of the 14 work goals on a 5-point scale, with “1” being “of utmost importance to me” and “5” being of “very little or no importance.”

Critiques of Hofstede’s cultural framework have sparked much passion and controversy (Trompenaars 1993; Hofstede 1996, 1997; Hamden-Turner & Trompenaars 1997). Some researchers (Ralston, Gustafson, Elsass, Cheung, & Terspstra, 1992) have criticized Hofstede’s approach as being culturally biased since the survey instrument from which these dimensions were derived was based on Western values. Although a valid criticism, developing a “culture-free” taxonomy would be impossible since any approach to understanding cultural differences will be constrained by the cultural orientation of its creators. Several other scholars have conducted follow up studies to gauge the extent to which similar dimensions and findings would emerge. Results of studies by Hoppe (1998) and Merritt (2000) suggest limitations in generalizability of the masculinity/femininity dimension.

Other criticisms of the masculinity/femininity dimension include overemphasizing conventional gender roles (Bem, 1975; Fagenson, 1990; Martin,1987) and declining differences in socialization of males and females in many countries (Segall, et al., 1990). To these criticisms, Hofstede and Vunderink (1994) responded that masculinity/femininity is a dimension of national culture, and…[is] not meant to describe individuals, but dominant patterns of socialization (“mental programming”) in nations; these dominant patterns will affect different individuals to different degrees, and some components of a national culture pattern may be found in one individual, while other complementary components will be found in other individuals within the same society (p. 331). Despite these criticisms, we decided to adopt Hofstede’s schema of masculinity/femininity as a tool for framing our results for two reasons: (1) the taxonomy is one of the most prominent and widely accepted frameworks for examining cross- cultural management; and (2) it is uniquely supported by empirical data from a large number of different countries.

Although culture is defined in many ways, from these studies, Hofstede came to define culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (Hofstede, 1980, p. 260). It is always a collective phenomenon, but collectives can differ from one another. Hofstede acknowledges that his shorthand definition of culture is incomplete and merely covers what he measured in his research (Hofstede, 1997). The results of these studies have become known as “Hofstede’s dimensions of national cultures.” Over the past three decades the majority of studies pertaining to cultural values have been influenced by the seminal work of Geert Hofstede.

Hofstede’s (1980) cultural framework was originally comprised of four dimensions that he named: Individualism/ collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and power distance. Within Hofstede’s study, a score on each of the four dimensions characterizes the culture of each of the fifty countries and that differed from country to country. The first of these dimensions is called power distance. Power distance reflects the ways in which individuals within a culture respond to inequality. Countries with low power distance (those with limited dependence of subordinates on bosses) rate a score closer to 0 while countries with high power distance (those with a considerable dependence of subordinates on bosses) rate closer to 100. Hofstede defines power distance as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

Collectivism/individualism is the second cultural dimension identified by Hofstede. The role of the individual versus the role of the group varies across cultures. Societies in which the interests of the group prevail over the interests of the individual are known as collectivist. In Hofstede’s study, those that place a higher value on individual interests are known as individualist countries and were given an Individualism Index score that was low (0) for collectivist and high (100) for individualist societies. According to Hofstede & Hofstede (2005), individualism relates to societies in which the connections between individuals are loose where societal members are expected to look after themselves and their immediate families. Collectivism as its opposite is experienced by community members through out one’s lifetime and are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

The third dimension defined in Hofstede’s study is called uncertainty avoidance. Feelings of uncertainty and the ways in which individuals learn to cope with them are part of the cultural heritage of societies. “Uncertainty avoidance can therefore be defined as the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 167). Uncertainty Avoidance Index values range from 0 for countries with the weakest uncertainty avoidance (a high tolerance for uncertaintly and ambiguity) to 100 for countries with the strongest (countries that rely on rules, laws and regulations to reduce its risks).

The fourth and final dimension of Hofstede’s study is masculinity/femininity, with masculinity on one end of the pole and femininity on the other end. A society is identified as higher in the Masculinity Index (MAS) when emotional and social roles are clearly distinct between genders: men are expected to be (and women may be) assertive, ambitious, tough and focused on material success where work prevails over family, but women are expected to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. A society is called feminine when emotional and social roles overlap between genders and both men and women are expected to be modest, caring and concerned with the balance and dual demands and responsibilities of family and work (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). The term “masculinity” for Hofstede’s study defines societies with distinct social gender roles, while the term “Femininity” defines societies in which social gender roles overlap and both sexes are expected to be tender and modest (Arrindell et al., 2004).

Our intuitive way of thinking about masculinity/femininity is to associate our stereotypes about men and women with the term masculine and feminine. It is very important to note that this is not the case with Hofstede’s dimension definition. For example, in a highly Masculine culture, as defined by Hofstede, both men and women can demonstrate toughness, ambition, materialism and assertiveness. The characteristics exhibited are not limited to either men or women. It is the culture that values any one or all of the associated male or female traits. Most importantly, a highly masculine culture has very clearly delineated gender roles. The higher the rating on the masculine dimension scale, the more that culture values clearly delineated gender roles. Women in highly masculine societies are encouraged to exhibit assertiveness, ambition and competiveness so long as it is within their culturally gendered role in the home, family and school, but not professionally in the workplace. In a highly masculine society it is normative for women to compete with one another, such as in an all female school, but competition between men and women is not expected or valued.

It should be emphasized that the Masculinity Index is one of Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture, not descriptions of individuals. It scores dominant patterns of socialization (‘mental programming’) in nations; these dominant patterns will influence perceptions of different individuals to different degrees. In other words, some components of a national culture pattern may be found in one individual, while other aspects descriptive of a national pattern will be found in other individuals within the same society. What is exhibited in individuals is the division of role expectations of men and women. In Masculine cultures, women can be competitive, ambitious, materialistic, etc. with one another and within the home, but it is not the norm for them to be so in the workplace.

The collective of individuals in a country carry “mental programs” (Hofstede & Vanderink, 1994) that are developed in the family in early childhood and reinforced in schools and organizations. These mental programs contain a component of national culture. They are most clearly expressed in the different values that predominate among people from different countries. Masculinity scored highest, respectively in Japan, Austria, Venezuela, Italy and Switzerland; it is moderately high in English-speaking Western countries; it is moderately low in such countries as France, Spain, Portugal, Chile, Korea and Thailand and lowest in the Netherlands and the Nordic countries.

For present purposes of exploring the ties between culture and leadership perceptions among women, this study focuses exclusively on the dimension of masculinity/femininity.

Hofstede’s Dimension of Masculinity/Femininity

Hofstede argued that gender and culture are both involuntary characteristics. They are acquired at such a young age that individuals within specific cultures conform to their culturally prescribed behaviors without question (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Masculinity and femininity refer to dominant sex role patterns in most traditional and modern societies; they generally refer to patterns of male assertiveness and female nurturance, respectively. According to these definitions, “masculinity” relates to the characterization of success and/or purpose in life, which allows both men and women to hold tougher values.

Italy’s Ranking on the MAS Index and Its Ties to Italian National Culture

Hofstede’s Masculinity Index (MAS) score was computed for each of the 50 countries in his study of IBM employee data. Scores ranged from 0 for the most feminine nationalities to 100 for the most Masculine (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Italy tied with Switzerland for fourth place on the MAS Index, with a MAS score of 70, indicating that Italy has a culture that is highly masculine (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Hofstede, et al.1998). The only countries studied that rank higher than Italy [and Switzerland (70)] were Japan (95), Austria (79) and Venezuela (73) respectively (Hofstede 1980). High-masculinity countries such as Italy have strong gender differentiation in their socialization of children and seek to maximize such differences. They offer children different role models based upon gender (fathers deal with facts and mothers deal with feelings). Girls are allowed to cry but not to fight and boys are allowed to fight but not to cry. Both genders are taught to uphold traditional family concepts (including gender roles), and fathers are the ones who decide family size (Hofstede & Hofstede 2005; Arrindell et al., 2004). Italian families socialize their children to be assertive, ambitious, and competitive. Italian organizations, in general, reward individuals based upon their individual results and performance. (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Thus, in general, Italian society and its organizations value and perpetuate masculine norms, defining Italy as a masculine culture.

Many religious values and laws continue to influence and to reinforce social norms prescribing distinct types of positions for women and men in the home and in the corporate world in positions of authority. (Hojgaard, 2002). Such values and beliefs limit opportunities for women who are seen as separate and subordinate in both career and family life, while enhancing and expanding the roles for men as patriarchs and providers. Traditional religious values and religious laws in Italy have played an important role in reinforcing social norms of a separate and subordinate role for women as homemakers and mothers, and a role for men as patriarchs with the family and primary breadwinners in the paid workforce (Inglehart & Norris, 2003). Not only do women in many societies hold different jobs than men do, and with lower status and rewards, but they are also expected to manage family responsibilities (Inglehart & Norris, 2003). Nowhere is this more prevalent than in Italy, where the Catholic Church has long exerted its influence on Italian families by promoting a specific set of values. Women were assigned the position of the “soul” of the family, while men were the “head”. Men were there to defend the family, while women nurtured the children.

Religiosity in Italy has exerted a strong influence on social norms about the appropriate division of sex roles in the home, the workforce, and the public sphere. The influence of religion in Italy is seen in the political sphere where the Democrazia Cristiana, DC (Christian Democrats) were in power uninterruptedly for 50 years. The Christian Democrats were succeeded by other parties also sharing the religious title, including the Christian Democratic Party, the United Christian Democrats and the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats, currently renamed the Italian Popular Party, but still illustrating the pervasive influence of Christian religious beliefs about gender roles in government organizations. After World War II, religious socialization and the pressures coming from Catholic organizations discouraged Italian women from taking more active roles outside the home. In later years, Italian women started to emancipate themselves and moved to close the gender gap (Corbetta and Cavazza, 2008), but even today, “the persisting effect of a gendered socialization should not be underestimated” (Campus, 2010, p.2).

Another issue to consider is the climate into which these female political leaders need to acclimate. According to Tinker (2004), most women, as well as men, still perceive men as more fit to govern in public spaces. In addition, many political sessions are scheduled in the late afternoon and early evening, a time not convenient to women with family responsibilities (Tinker, 2004). Such a barrier evokes the “second-wave” feminist arguments of the contradictory experience called “double presence” (Balbo, 1979); a term used to describe women in the 1970’s who typically worked full time in addition to long hours of work at home. Clearly, the male-dominated political culture in more masculine countries remains an obstacle to women’s political leadership and advancement.

Methodology

The authors conducted in-depth interviews with fourteen Italian women of different social strata, identified as leaders in the fields of employment and research. This study utilizes and builds upon the theoretical model identified by Geert Hofstede (1980) — the masculinity/femininity dimension of national cultures. Our interviewee’s responses to the interview questions were examined and analyzed using Hofstede’s masculinity/femininity dimension as a theoretical grounding to examine the data gathered for this study. The distinct gender roles characterized within Italy’s masculine culture provide insight into that society’s values surrounding women and leadership. Through our research and analysis, we explored how women participate in their society in ways that challenge the cultural hegemony and contribute to the nation’s leadership.

Interviewees

To answer our questions, fourteen women, born and raised in Italy – identified by their peers as leaders in their chosen fields of employment, research and social strata – were interviewed about their leadership perceptions and experiences. Using a snowball sampling methodology (Spreen,1992; Faugier & Sargeant,1997; Vogt, 1999), fourteen prominent Italian women were selected for this study based upon their leadership position, reputation, and effectiveness in Italy (Appendix B). Our research team started a search for women perceived in their society with Who’s Who in Italy; then contacted 100 of the listed women in a variety of fields; from those, got suggestions for others to interview. The women selected were perceived by their colleagues and professional associations to demonstrate important skills, traits and styles associated with effective leaders; the snowballing referrals included mention of emotional and social intelligence, self-management, the ability to catalyze commitment and influence others to pursue a clear and compelling vision, and the capacity for and interest in life-long learning (Bennis, 1989; Burns, 1978; Conger, 1998; Boyatzis & McKee, 2005; Heifetz, 1994; Kouzes & Posner, 1995; Avolio, 1999, 2005). We define leadership as ‘the process of being perceived by others as a leader’ (Lord & Maher, 1991, p.11). Lord and Maher (1991) have argued that leadership perceptions are an important consideration since one must first be perceived as a leader to be allowed the necessary discretion and influence to perform effectively. Similarly, Hofstede (1993) stated that “managers derive their raison d’etre from the people managed: culturally, they are the followers of the people they lead, and their effectiveness depends on the latter” (p.93).

The women chosen for this study are viewed as leaders precisely because they are perceived as possessing leadership behaviors, traits and characteristics (House & Aditya, 1997; Lord & Maher, 1991). Being Italian born and raised was a requirement for inclusion in the study. Eleven of the interviewees are married, three are single and eleven of them are mothers. The women’s ages ranged from mid-40s to mid-70s. Eleven have earned at least one European university degree (the equivalent of an American bachelor’s degree), one completed three years towards her university degree, while two hold doctorates. Two are journalists and broadcasters; two are politicians; one is a college professor; one is a marketing professional and president of her own company; one is a writer, historian and women’s activist; one is an executive director of a major Italian commission; one is a lawyer; one is a psychologist; one is a physician of geriatrics; one is an administrator in a healthcare organization; one is owner of brokerage firm; and one is a doctor of radiology. All interviews were conducted in (as interviewees proudly referred to it) the “Eternal City” of Rome, at the interviewees’ places of employment.

Structured Interviews

A series of interview questions (see Appendix A) was asked of the interviewees. Questions were identical for all participants, focusing on four major categories: (1) identifying lifeline or defining moments, (2) perceptions, values, memories and self perceptions around leadership, (3) definitions and perceptions of success and achievement, and (4) finding meaning in one’s life space. Four of the fourteen interviews were conducted with the assistance of translators. Each interview lasted from ninety minutes to two hours, and the same questions were consistently asked of each interviewee. The interviews were conducted over a period of twelve days in June of 2006. While the same questions were consistently asked of each interviewee, individualized follow-up and probing questions were asked of participants for clarification and elaboration. Interviews were audio- and video-taped for multiple backups, and the on-site researchers concurrently took handwritten notes. Taped interviews were later transcribed.

The transcriptions were then checked for accuracy, consistency and completeness. To ensure completeness of the transcriptions, the researchers went through multiple iterations of listening to the tapes and again rechecking the coding in our notes and consistency of themes. Following this auditing process, extensive notes were taken from the transcripts. Transcriptions were then organized to identify emergent themes. The first author checked for any omissions and/or inaccuracies. Themes were then examined by the authors to identify those that related to the masculinity/femininity aspect of Hofstede’s dimensions of national cultures. The researchers then organized the findings into themes and sub themes and related these to the MAS Index ranking for Italy.

Interview coding

Characteristic of qualitative research and grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), the emergent themes were sorted into meaningfully relevant categories from the interview data collected. Qualitative data analysis is a continuous, iterative process (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The notes taken during the interviews and from the transcriptions were organized into themes reflective of the interviewees’ responses. The themes were then further refined and a conceptual framework was created within which the interview data themes could be interpreted. Our interview data revealed three key areas in our interviewees’ perceptions of leadership: 1) family, 2) education, and 3) profession, which were discussed in equal proportion.

Results

On the top of Gianicolo Hill in Rome sits a larger-than-life statue of Anita Garibaldi, the wife and comrade-in-arms of Italian revolutionary, Giuseppe Garibaldi. The statue depicts Anita Garibaldi, mounted on a rearing horse, holding her baby son close in her left arm while brandishing a pistol in her right hand, as she leads her husband’s army to victory. The statue was completed and presented to the City of Rome in 1932. It is a testament to the dual burden of women in Italian society as fierce, brave, and mighty warriors and, at the same time, as nurturing, protective—and beautiful—mothers. This same dualistic nurturing and commanding presence was found in the fourteen women interviewed for this study. While not as well known in Italy as the late Anita Garibaldi, our interviewees have power and influence, are intensely nurturing of others—and are making a difference as leaders in Italian society.

Our results show that not only are women in Italy expected to lead outside the home, but they are also expected to lead inside the home. This means consistently attempting to walk a tightrope, having to manage two very different sets of demands, in a way that does not apply to men. As leaders, women are expected to adapt in ways that men are not. Our data provides some insights into these cultural expectations and furthers our understanding of the interaction of culture and female paths to leadership in Italy.

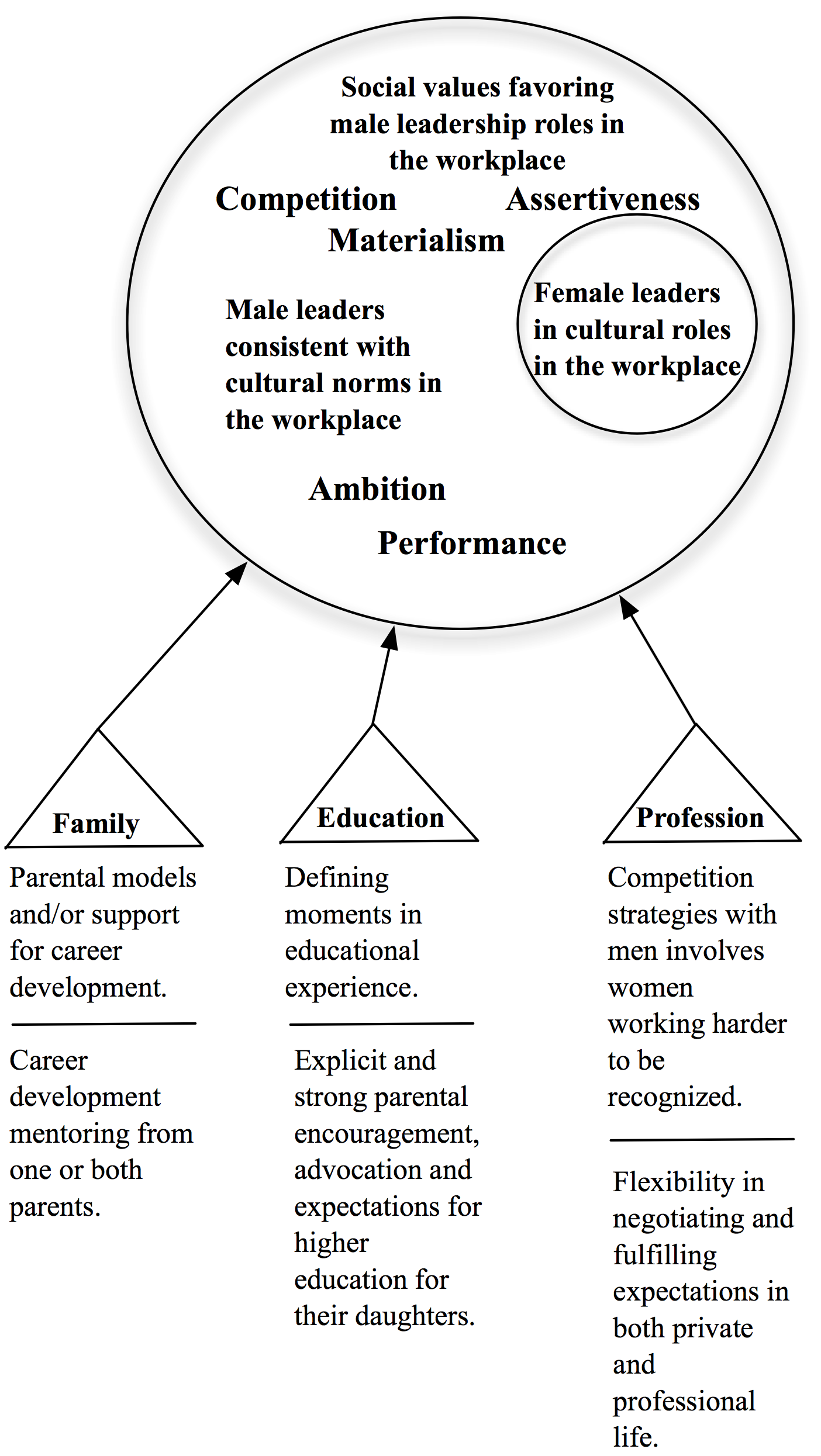

While both men and women are socialized to be ambitious, we must note that the masculine cultural norm insists upon upholding traditional family values. Women in countries with high MAS norms and values are expected to lead outside the home and inside the home. This means consistently attempting to strike a balance between personal and professional life. Our interview data revealed three domains and, six themes within those leadership domains: 1) Family-parental models and career mentoring 2) Education-experience and parental encouragement and 3) Profession-competition strategies and flexibility.

Family and Leadership

In evaluating the transcripts from the interviews, it is clear that Italy’s masculine cultural traits played a large role in not only the families of origin of the women interviewed, but also in the families that these women later established with their spouses. The mere fact that these women are leaders in their respective fields supports Hofstede’s claim that both Italian women and men are socialized to be ambitious and competitive. Several of the women interviewed had both parents active in the workforce, thus providing role models. All our interviewees were mentored by one or both parents that supported the masculine values in Italian culture. In the words of one interviewee, “Both of my parents have contributed to leading me to this path. My father was an intellectual in the Italian left party and my mother was the first woman to be the Vice President of the House of Deputies here in Italy. Good mentors”. Table 1. illustrates our two themes from our domain of family and leadership with a sample of relevant interview responses.

Table 1. Interview DataFamily and Leadership ThemesSample Relevant Interview Responses by Participant |

||||||||||||

|

One interviewee, who had graduated with a bachelor’s degree in foreign language and literature while living in Italy, applied for and was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to study in the United States. She later receiving her Ph.D. from Yale University and was a professor at American University in Rome at the time of this interview. She grew up in a small village in southern Italy, and recalled that her “family was very happy, but my peers, especially my girl friends, were really shocked. They felt my decision [to leave for the U.S.] was very disruptive of friendship relationships…it was a decision I made against their view.” She further reflected, “I can see I really made the decision on my own, even if I went against the grain, against my friends….” She summed it up by saying, “This is a balance that requires continuous negotiation and effort.” Although this interviewee calls the management of her demands to be a “balance”, it is more like a balancing act, an issue of feeling as if on a tightrope with extra things to consider and manage.

Twelve of our interviewees made some reference to the importance of the difficulty of trying to strike a balance between their families and their professional lives.

Such pressure is not a surprise: according to the masculine Italian culture, women are expected to succeed and lead in both work and family. Another interviewee, a journalist, stated, “I would love to travel more for my work, but then I wouldn’t be able to spend time with my daughter, so I have to be satisfied with what I have.” Clearly, for the women in Rome, leadership comes with a price tag. If they want to be leaders at home, they must sacrifice some aspect of their professional lives, and, conversely, if they want to be leaders in their professional lives, they will have to give something up in their family lives. In the “masculine” culture of Italy, women are expected to live up to two standards. They are expected to be nurturing and caring as the leaders of their families, but also competitive and aggressive when they enter the workforce. In short, these women are expected to uphold dual roles that are equally important and to excel at both.

Education and Leadership

The second key factor influencing our subjects’ perceptions of leadership was the impact and role of education in our interviewee’s lives. In his research, Hofstede uncovered cultural differences between masculine and feminine countries in relation to education. “In the more feminine cultures the average student is considered the norm, while in more masculine countries…the best students are the norm” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 90). Therefore, in masculine cultures like Italy, students compete openly with each other and strive to be visible in classroom situations.

Additionally, failing is a disaster in countries with a high MAS Index ranking, giving weight to the idea that students in masculine cultures are expected to perform at their best at all times and under all circumstances. Many parents view schooling as a vehicle for their children’s social mobility (Krause, 2005). The parents of our interviewees understood that higher education offered a path and hope for their daughters to overcome traditional barriers for professional advancement. They were explicit about their expectations and strongly encouraged their daughters’ pursuit of higher education. Interviewees also discussed the significance of higher education in defining their leadership. Table 2. illustrates our two themes from our domain of education and leadership with a sample of relevant interview responses.

Table 2. Education and Leadership ThemesSample Relevant Interview Responses by Participant |

||||||||||

|

The educational environment provided opportunities at all ages for our interviewees to practice their leadership capabilities. One interviewee spoke a great deal about her perceptions of her need to succeed in the Italian educational system. She talked about how a female teacher chose her in grade school to be the student to initiate class conversations: “breaking the ice in class became my role, so slowly I began to be intrigued by it and I started to prepare for it.” Even at an early age, this interviewee said that she wanted “to put her best foot forward,” a trait she had learned from growing up in her Italian masculine culture. Having gone on to become a member of the faculty at an Italian university, our interviewee described her first-hand experience with the lack of female faculty representation at the university in which she taught and how men marginalized her. She said that although the position she filled existed since 1969, “I am the first Italian woman to be hired as a full-time professor here at this institution. At first, the men [at the university] had a hard time decoding me as an Italian woman. They had certain ideas about me that did not correspond with the way that I behaved so I had to earn their trust.” Although ambition and assertiveness is valued in Italy, so are clearly defined gender roles. Our interviewee displayed a counter cultural role attempt and was marginalized as a consequence.

Each of the interviewees noted that her family’s expectation for educational attainment were very high. One of the interviewees who established her career in journalism and broadcasting noted, “My parents wanted me to graduate [from] a university. My parents didn’t have degrees so they wanted me to have one.” She was encouraged by her parents to get a degree and to use it in a career.

Although all fourteen of our interviewees were encouraged to excel in school, they still faced the challenges in gendered cultural expectations once they arrived in the workforce. As one stated, “Women in Italy have become more visible as public figures since the time when I was growing up. This is very encouraging. There are more women getting BAs than men. My concern is that I don’t see that the mentality of the culture has changed. They are getting better education but they are getting (fewer) jobs. Even if they have the opportunities, they don’t take them.” The issue is that women are expected to be competitive, but only within the female domain of the home, the family and school, if it is an all-female school. Competition between women is valued, but not between men and women.

Statistics bear out our interviewee’s concerns: while Italy has a comparatively high share of women with tertiary education (132 women for every 100 men), female employment has stalled among women with University credentials (Eurostat UOE, 2008). A Eurostat study in 2008 found that Italian female University educated graduates accepted lower status jobs (e.g. clerks, service and sales workers) almost twice as often as men with the same level of education: 13.6% compared to 7.6%. (Eurostat UOE, 2008). In addition, women with the same level of education as men were more likely to be unemployed (Eurostat, 2008).

Despite the disparity in educational attainment to job status, women’s overall employment rate is steadily increasing. In 2010, the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) estimated the employment rate to be 51.2%, an almost 9% increase for Italian women from three years earlier. So, while Italian women are encouraged to obtain more education, there is still the question of whether or not this education will lead them to be valued members of the workforce. This discrepancy between educational and workplace expectations will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

Profession and Leadership

While the family in masculine cultures socializes children to be assertive, ambitious and competitive, organizations in these cultures stress results and offer rewards based upon performance. Managers in masculine cultures are expected to be assertive and decisive, thus reinforcing the early socialization of children in these cultures. “In Italy, to be ‘forceful’ is more desirable for both genders…” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 1998, p. 98). In a masculine society the ethos tends more toward “live in order to work”, whereas in a feminine society the work ethos would be “work in order to live.” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 1998, p. 94).

Although the interviewees fit such “masculine” cultural norms, they still practiced a “feminine” leadership approach associated with women; cooperation, mentoring, and collaboration, along with other characteristics associated with transformational leadership (Burns, 1978) and charismatic leadership. (Conger & Kanungo, 1998) The “feminine”– empathy, community, collaboration, vulnerability and skills of inquiry — approach to leadership (Calvert & Ramsey, 1992; Fletcher, 1994; Fondas, 1997) should not to be confused with Hofstede’s definition of a feminine culture. Table 3. illustrates our two themes from our domain of profession and leadership with a sample of relevant interview responses. All the interviewees talked about their need to work harder than their male colleagues in order to be recognized and valued.

Table 3. Profession and LeadershipTheme Sample Relevant Interview Responses by Participant |

||||||||||||||

|

The interviewees described themselves as leaders who were able to do many things at once. Flexibility in negotiating and fulfilling expectations in both their private and professional lives was a second theme in the domain of profession and leadership. One interviewee, a marketing professional, stated that, “women have a more flexible way of thinking.” Another interviewee, who works in broadcasting, described flexible thinking as “part of their inner selves”. The leadership ideals expressed by the participants in this study diverged from the assertive and decisive attributes valued by a masculine society in Hofstede’s findings. While these women could certainly be described as assertive and decisive, they utilized a more communal leadership style than that revealed in Hofstede’s IBM research. Another interviewee, a long-time philanthropist, describing her own leadership style stated, “Leadership is forming a group of people to work for the good of everyone…I look at what a person is thinking or what they believe and like a person who knows how to create synergy…It’s very important in a job because you can’t express leadership unless you can bring everyone together …and then find the best solution which comes from synthesizing everyone’s facts, ideas and opinions.” The business owner interviewee added, “Leadership is not about being the boss. It is about working as a group, following the needs of the group members and then making a decision that is best for the whole.”

The way in which our interviewees describe leadership and the way in which they themselves lead, while assertive and decisive in the end is a communal approach to the process. As a traditionally marginalized population of leaders in the workforce, these women have learned to negotiate their styles of leading within a masculine normative culture, as depicted in figure 2. Here we summarize three converging streams of influence — Family, Education and Profession — all of which come together to create a woman leader in Italy: All roads lead to Rome!!

Conclusions and Implications

Hofstede’s research on the dimension of masculinity/femininity provides a frame for a deeper understanding about cultural factors influencing women leaders in Italian society. Our interviews with fourteen women supported Hofstede’s research that the “masculine” culture reinforces separate gender roles for women and men and further extends the model to incorporate perceptions about women’s leadership development in Italian society. Women leaders face many challenges in such “masculine” cultures. The gender norms submitted in Hofstede’s research support the notion that progress in society has not eased the burden on women but has made it even more complicated. To conform to the norms of Italian society, women can certainly be leaders in the workplace, but only in conjunction with their responsibilities in their homes and with the awareness that they are forging a new path in Italian society. Thus, the model within the culture actually allows a pathway to female leadership, but only if you can do both family and profession simultaneously. The cultural norm is that under no circumstances can women abandon the house.

Our interview data reveal that there are two distinct issues. One is that the demonstration of individual traits of ambition, competition and materialism by women are fine as long as they are within the culturally defined domain. The second issue is that there is a pathway to leadership, but only if you can keep up all your responsibilities in the household, a dual demand not acting on men in in Italian culture. These are huge conclusions to draw on fourteen women. However, they are fourteen very prominent women in a country with very few women in leadership positions from which to collect our data. We view these women as particularly good embodiments of what it takes to be a female leader.

It is not surprising that for women to ascend to leadership positions in the workplace in a “masculine” society, the burden for change is placed on women rather than upon men. (Hofstede, 2001) Our findings teach us the importance of parental leadership, influencing their daughter’s leadership potential in society by supporting and nurturing her development to realize her potential as a contributing member of Italian society. Our interview findings also illuminate women’s persistence in masculine cultures to pursue their dreams and live their values in nurturing their own families, acquiring higher education, and leading in their chosen professions.

Our research and the research of others, point to women’s roles in Italy evolving further over the next decade. Managers in organizations need to remain vigilant to avoid remaining in the status quo. There are many actions that an organization’s leadership can take so that Italy may increase the numbers of women who actively engage in leadership roles in Italian institutions. Through mechanisms in the organization, such as training, reward systems, recruitment, selection, and promotion, a leader can transmit and embed values in an organizational culture (Jaskyte 2004). At the same time, the organizational culture influences the characteristics (including the gender characteristics) selected for a leader (Schein 1992), as well as how subordinates perceive the leader’s performance (Denison and Mishra 1995).

Schein (1985) asserts that good managers must work from a more anthropological model. Although difficult, it is possible to change culturally held beliefs about women’s leadership role, but change requires an organization’s leadership to alter its traditional beliefs, expectations, policies and practices about women at work. Maier (1992) studied changes in assumptions and implications for women in positions of influence in the workplace in the United States from the 1950’s through the 1900’s resulting in a work environment today where “men and women can both be ‘like women’ and ‘like men’ and where interdependence between work and family is acknowledged” (p. 31). Schein further indicates that there are two problems all organizations must address. The first is survival, growth, and adaptation in the environment and the second is internal integration that permits functioning and adapting.

It is clear that effective women leaders provide a resource that Italian and other societies desperately need for survival and growth in our global economy. It is beholden upon our organizations to learn to integrate and adapt to women’s transformational leadership styles that promote positive organizational change. Rather than merely symbolic gestures of support, those in human resources management positions, with the power to initiate, implement and champion change, can affect the criteria with which women are promoted.

Organizations that set different criteria for advancement, in turn affect those who will have access to high-ranking positions (Addi-Raccah, 2005). Additionally, changes in work-life balance practices and policies and changing the conventional cultural attitudes toward gender-specific roles are likely to promote more women into positions of power (Inglehart & Norris, 2003; Norris, & Inglehart, 2001). Finally, both men and women in the organization must be systemic and visionary in their thinking. They must mentor and deliberately support the development and success of women in the organization, especially if a quota system is adopted and implemented. As this study illustrates, women in Italy are making their mark at the top, in spite of existing cultural resistance. The authors expect that the decade ahead will see women evolve further into leadership positions as Italian women as well as men deliberately resist the temptation of the cultural status quo and more laws are passed to further gender equality.

Yet many questions remain: How much change has occurred within Italian society? How can more women leaders make a difference? What is the impact on men’s roles? What is the impact on family values and the concept of “traditional” values? Are new marriages based on a different set of values than in the past? If so, what are they and how will they affect the children growing up in the “masculine” culture of Italy? Because of the changing role of women in society over the last few decades and their related ascent to leadership positions, a new study of the dimension of masculinity/femininity may be beneficial to a contemporary understanding of Italian women and leadership.

Further research is needed in looking at differences in male and female leadership styles in highly “masculine” societies, such as Italy. Our research provides an in-depth personal look at how cultural gender values impact individual lives and leadership ascension in Italy. Further studies of women in other countries using Hofstede’s model, would provide deeper and more extensive data about cultural challenges to developing female leaders and sustaining their ascension to leadership positions in societies and organizations.

Limitations and Future Directions

Given the recent emergence of multicultural studies about women in leadership, coupled with the challenges of cultural research, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions solely based on the present study. Our modest sample size limits the generalizability of our results to all of Italy, let alone other masculine cultures. By illustrating these preliminary findings in terms of women’s perceptions about leadership development and their challenges in a masculine society, we hope to encourage more extensive and rigorous research in Italy as well as cross-cultural research aimed at identifying similarities and differences in female leader perceptions about challenges and opportunities in the context of cultural dimensions within and between countries.

Another potential limitation includes the use of Hofstede’s multidimensional scaling procedure to provide an overall understanding of the proximity of Italy in terms of cultural perceptions of men and women about family, education and profession to help interpret our findings. This is a qualitative analysis technique that relies on subjective interpretation. Hofstede notes, however, that the masculine/feminine dimension, along with his other dimensions, are merely “tools for analysis that may or may not clarify a situation” (1993, p.89). This general taxonomy of cultural dimensions was useful in interpreting leadership perceptions and challenges faced by our Italian women interviewees, and that it may continue to serve as a meaningful framework for future research of this kind.

Appendix A: Interview Questions

I. Lifeline

- What were defining moments? What events stand out in your accomplishments?

- What were your expectations for yourself and from significant people in your life while growing up?

- Has anyone discouraged you from achieving your goals?

- Who were your significant mentors and how did they empower you?

- When you are in crisis, where do you go to get advice? Or, What has allowed you to overcome predicaments?

- What holds you together when you are feeling this way and on a daily basis?

II. Leadership

- What are your first memories of being a leader?

- How do you think of leadership? What does it mean to you?

- What are your beliefs and values about leadership?

- How would you describe yourself as a leader?

- Has your leadership style changed over the years? If so, how has it changed?

- Do you anticipate it changing further in any way?

- Who were significant role models in your life and how did they influence you? Or, who was a model for you to follow?

- How good a follower are you? Whom do you follow?

- Whom do you admire? What historical or contemporary world figure would you like to sit next to for ten hours on a plane?

- How do you see your own power and the ability to influence others?

- What is your experience in working with men in your organization?

- Have you ever felt marginalized as a woman in an organization where you worked or in your family?

III. Achievement

- How did you define success at the beginning of your career? How do you define success now? How will you define it at age 70?

- When did you begin your current position?

- How long do you expect to stay in your current position of leadership?

- What do you think defines the difference between your leadership experience and those of men from your perspective?

- When do you expect to retire?

- What makes you happy?

IV. Meaning/Life Space

Instructions: Consider for a moment the things that matter to you most in your life right now.

- How would you allocate 100% among those things in order of their importance to you right now?

- Which of those things are you most passionate about, value most deeply and why?

- Where do you go to get inspiration?

- Do you find time to be reflective? When and how?

- Do you feel your work and personal life are in balance?

- What is your vision for yourself, your family, your community,

*Adapted from: Bennis, W. & Thomas, R. (2002). Geeks and geezers: Leading and learning for a lifetime. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

References

Addi-Raccah, A. (2005). Gender, ethnicity, and school principalship in Israel: Comparing two organizational cultures. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 9(3), 217-239.

Aaltio, I. & Mills, A. (2002). Gender, identity and the culture of organizations. New York: Routledge.

Arrindell, W. A., Eisemann, M., Oei, T. P. S., Caballo, V. E., Sanavio, E., Sica, C., et al. (2004). Phobic anxiety in 11 nations: Part II. Hofstede’s dimensions on national cultures predict national-level variations. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 627-643.

Avolio, B. (1999). Full leadership development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Avolio, B. (2005). Leadership development in balance. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Balbo, L. (1979). La doppia presenza. Inchiesta. 8(32), 3-6.

Baxter, J., & Wright, E. O. (2000). The glass ceiling hypothesis: A comparative study of the United States, Sweden, and Australia. Gender & Society, 14(2), 275-294.

Bellavigna, E. & Zavanella, T. (2010). Donne: motore per lo sviluppo e la competitivita. Gea-Consulenti Associati.

Bem, S.L. (1975). Sex role adaptability: One consequence of psychological androgyny. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 31, 634-643.

Bennis, W. (1989). On becoming a leader. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Bennis, W. & Thomas, R. ((2002). Geeks and geezers: Leading and learning for a lifetime. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Boyatzis, R. & McKee, A. (2005). Resonant Leadership. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Burns, J. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Bruins, J., Den Ouden, M., Depret, E., Extra, J., Gornik, M., Iannaccone, A., et al. (1993). On becoming a leader: Effects of gender and cultural differences on power distance reduction. European Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 411-426.

Calvert, L., & Ramsey, V.J. (1992). Bringing women’s voice to research on women in management: A feminist perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 1(1), 79-88.

Campus, D. (2010). Political Discussion, Views of Political Expertise and Women’s Representation in Italy. European Journal of Women’s Studies. 17(3) 249-267.

Carbert, L. (2003). Above the fray: Rural women leaders on regional development and electoral democracy in Atlantic Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 35(1), 159-183.

Chisholm, L. (2001). Gender and leadership in South African educational administration. Gender and Education, 13(4), 387-399.

Conger, J. & Kanungo, R. (1998). Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dahlerup, D., & Freidenvall, L. (2005). Quotas as a ‘fast track’ to equal representation for women. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 7(1), 26-48.

Datta, K., & McIlwaine, C. (2000). “Empowered leaders?”: Perspectives on women heading households in Latin America and Southern Africa. Gender and Development, 8(3), 40-49.

de Beauvoir, S. (1993). The Second Sex (H.M. Parshley Trans.). New York. Knopf Publishing. (Original work published 1949).

de la Rey, C., Jankelowitz, G., & Suffla, S. (2003). Women’s leadership programs in South Africa: A strategy for community intervention. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 25(1), 49-64.

Denison, D. R., & Mishra, A. K. (1995). Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6, 204–223.

Dorfman, P. W. (1996). International and cross-cultural leadership research. In B. J.

Punnett & O. Shenkar (Eds.), Handbook for international management research (pp. 267-349). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Eagly, A. (1987) Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Eagly, A. & Carli, L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Ecklund, E. H. (2006). Organizational culture and women’s leadership: A study of six Catholic parishes. Sociology of Religion, 67(1), 81-98.

Eurostat. (2009). Key Data on Education in Europe [Data File]. Retrieved from http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/978-92-9201-033-1/EN/978-92-9201-033-1-EN.PDF

Fagenson, E.A. (1990). Perceived masculine and feminine attributes examined as a function of individuals’ sex and level in organizational power hierarchy: A test of four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology. 75, 204-211.

Faugier, J. & Sargeant, M. (1997). Sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing. (26), 790-797.

Ferraro, G.P. (1990). The Cultural Dimensions of the International Business. New Jersey. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Fletcher, J.K. (1994). Castrating the female advantage. Journal of Management Inquiry, 3(1), 74-82.

Fondas, N. (1997). Feminization unveiled: Management qualities in contemporary writings. Academy of management Review, 22, 257-282.

Frost, P. (1985). Organizational Cultures. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1994). Cross-cultural comparison of leadership prototypes. Leadership Quarterly, 5(2), 121-134.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine Publishing.

Goodman, D. S. G. (2002). Why women count: Chinese women and the leadership of reform. Asian Studies Review, 26(3), 331-353.

Gregory, K. (1983). Native-view paradigms: multiple culture and culture conflicts in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly. 28(3), 359-76

Griggs, C. (1989). Exploration of a feminist leadership model at university women’s centers and women’s studies programs; A descriptive study. University of Iowa: UMI Dissertation Services.

Hampden-Turner, C. and F. Trompenaars (1997). Response to Geert Hofstede. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21 (1), 149-159.

Heilman, M., Wallen, A., Fuchs, D. & Tamkins, M. (2004). Penalties for Success:

Reactions to Women Who Succeed at Male Gender-Typed Tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology. 89(3), 416–427.

Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work related Values; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constrains in management theories. The Executive. 7(1), 81-94.

Hofstede, G. (1996). Riding the waves of commerce: A test of Trompenaars’ “Model” of national cultural differences. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(2), 189-198.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Riding the Waves: A Rejoinder. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21(2), 287-290.

Hofstede, G. (1998). A case for comparing apples with oranges: International differences in values. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 39(1),16-30.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G., Arrindell, W. A., Best, D. L., De Mooij, M., Hoppe, M. H., Van de Vliert, E., et al. (1998). Masculinity and femininity: The taboo dimension of national cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. & Vanderink, M. (1994). A case study in masculinity/femininity differences: American students in Netherlands vs. local students. In A.M. Bouvy, E.J.R. van de Vijiver, P.Boski. & P. Schmitz (Eds.). Journeys into cross-cultural psychology (pp.329-347). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hojgaard, L. (2002). Tracing differentiation in gendered leadership: An analysis of differences in gender composition in top management in business, politics and the civil service. Gender, Work and Organization, 9(1), 15-38.

Hovden, J. (2000). Gender and leadership selection processes in Norwegian sporting organizations. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 35(1), 75-82.

House, R., Wright, N., & Aditya, R. (1997). The social scientific study of leadership: Quo Vadis? Journal of Management, 23(3), 409-73.

House, R., Wright, N., & Aditya, R. (1997). Cross-cultural research on organizational leadership: A critical analysis and a proposed theory. In P. C. Earley & M. Erez (Eds.), New Perspectives in International Industrial Organizational Psychology (pp. 535-625). San Francisco: New Lexington.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Inkeles, A. & Levinson, D. (1969). National character: the study of modal personality and sociocultural systems. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.). Handbook of Social Psychology, 418-506. New York: McGraw-Hill. (Original work published 1954) Inter-Parliamentary Unit. (2010). Women in National Parliaments [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm#2

Inter-Parliamentary Unit. (2010). Women in National Parliaments [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm

Italian Institute for Statistics. (2010). Labour Market Indicators by Sex and Geographic Region [Data file]. Retrieved from http://en.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/

http://en.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/in_calendario/forzelav/20100624 00/labourforceI_2010.pdf in_calendario/forzelav/20100624_00/labourforceI_2010.pdf

Jaskyte, K. (2004). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership. 15, 153–168.

Kawahara, D. (2007). “Making a difference”: Asian American women leaders. Women & Therapy, 30(3/4), 17-33.

Kouzes, J.M. & Posner, B. (1995). The Leadership Challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Krause, E. (2005). A crisis of births: Population politics and family-making in Italy. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Krook, M.L. (2006). Reforming representation: The diffusion of candidate gender quotas worldwide. Politics & Gender, (2), 303-327.

Li, H. (2001). Leadership: An international perspective. Journal of Library Administration, 32(3/4), 169-186.

Lipman-Blumen, J. (1984). Gender Roles and Power. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lord, R.G., Foti, R.J. and Devader, D.L. (1984). A test of leadership categorization

theory: internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34(3), 343-78.

Lord, R.G., & Maher, K.J. (1993). Leadership and information processing: Linking perceptions and performance. New York: Routledge.

Maddock, S. & Parkin, D. (1993). Gender, cultures: Women’s choices and strategiesat work. Women in Management Review. 8(2), 3-9

Martin,C.L. (1987). A ratio measure of sex stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52, 489-499.

Meindl, J., Erlich, S. & Dukerich, J.(1985). The romance of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(3), 78-102.

Merritt, A. (2000). Culture in the cockpit: Do Hofstede’s dimensions replicate? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 283-301.

Miles, M, & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nadeau, B. (2010, November). Italy’s woman problem. Newsweek. Retrieved from: http://www.newsweek.com/2010/11/15/bunga-bunga-nation-berlusconi-s-italy-hurts-women.html

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2001). Cultural obstacles to equal representation. Journal of Democracy, 12(3), 126-140.

Ozkanl, O., & White, K. (2008). Leadership and strategic choices: Female professors in Australia and Turkey. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 30(1), 53-63.

Owen, R. (2008, 2.28). Meet Italy’s most powerful woman, Emma Marcegaglia. The Sunday Times. Retrieved from http://women.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/women/article3448897.ece

Ralston, D.,Gustafson, D.,Elsass, P., Cheung, F.,& Terspstra, R. (1992). Eastern values: A comparison of managers in the United States, Hong Kong, and the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Applied Psychology. 77, 664-671.

Rodman, H. (1972). Marital Power and the theory of resources in cultural context. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 3, 50-57.