Russ Volckmann

Abstract

The terms integral, leadership and diversity are explored with the purpose of showing how it is useful to consider them in relation to each other. Such consideration is significantly impacted by how we understand these and other terms that will be introduced. It is essential for us to appreciate how our approaches to meaning and sense making influence how we make choices about what is relevant, how we engage with these choices to implement efforts toward learning, development and change. Our concepts of leadership play essential roles in our achievements and our failures. Greater clarity can be achieved by reserving such concepts to communicate with less ambiguity and by using specific occurrences to generate context specific definitions. Such an effort is greatly enhanced by attending to the perspectives offered by mapping and theory built on the work of Ken Wilber and others.

Introduction

The key terms in the title of this article suffer from ambiguity in their definitions. Each carries the baggage of many definitions that are only partially shared, but they act as mental maps, sources of association for each of us. The relevance of this observation for comprehending the relationship between leadership occurrences and the role of diversity and differences is increasingly pronounced as globalization and growing ecological crises demand ever greater complexity in the human resources we bring together to address these challenges. In this article I offer an approach to considering the relationship between leadership and its aspects, on the one hand, with the phenomena of diversity and differences in engaging change and sustainability, on the other hand. Furthermore, I emphasize the importance of our choices in the use of terms that can be leveraged for both their ambiguity and contextual clarity.

The term integral is applied in at least two ways in the literature that has emerged in recent years. Integral has its advocates from those who follow the work of Ken Wilber (2000, 2007), Ervin Laszlo (2003) and/or Sri Aurobindo (2010), for example. Following the work of Jean Gebser (1984), it is used in reference to a postconventional level of spiritual awareness or consciousness development (Wilber 1995, 2007). Secondly, it has come to be known as a type of theory or metatheory (Edwards 2010). There are other models and conventions for labeling stages or levels of development as used by Wilber or in adult developmental psychology (Beck and Cowan, 1997; Kegan, 1982; Cook-Greuter, 2010; Torbert et al, 2004). In this article integral refers to theory or metatheory. I will use other terms for stages of development, while acknowledging the valuable role of stage theories of adult development in sense and meaning making and construction of mental maps.

It is well known in leadership studies that several hundreds of definitions have been offered for the term leadership and that none has been selected as a basis for building a field of study (Bennis and Nanus 1985). This has been explored by Rost (1991) and more recently by Riggio (Harvey and Riggio 2011) and Kellerman (2012). In the most recent of these works, Kellerman (xxi) estimates fourteen hundred definitions of leadership and forty-four theories of leadership. This certainly calls for an approach that can create some order out of the chaos while enhancing our ability to appreciate leadership occurrences in varying contexts and the qualities and relevance of diversity and differences. In order to support such an effort, I would encourage us to examine the language of leadership and diversity in order to suggest frameworks on a higher/broader basis while refining terms to meet contextual idiosyncrasies. In order to do this I suggest an approach that holds distinctions to be primary and definitions to be derivative. Within distinctions we have the guides for definition.

The term diversity points to differences along the dimensions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs, or other ideologies, and more. Note this description of diversity in one type of context, education:

A class with significant academic diversity is characterized by students achieving in the average, above-average, and below-average range of academic performance as measured by teacher, school district, or state academic standards. This diversity in performance may be attributed to the interaction between individual differences among teacher and students in, but not limited to, learning needs, emotional needs, culture, gender, life experiences, life situations, age, sexual orientation, physical abilities, cognitive abilities, behavior, skills, strategies, language proficiency, beliefs, goals, personal characteristics, and values (Lenz, Deshler and Kissam, 2004, p. 2).

Gregory and Rafanti (2010) have demonstrated how the meanings we attach to the term “diversity” shape how we engage with phenomena we identify as involving differences on many levels and in many domains. Furthermore, they associate with the integral notion of adult development a characteristic of stages of development involving “diversity maturity,” that is, postconventional stages demonstrate higher levels of diversity maturity (p. 50) Their work is focused on the increasing capacity of individuals at higher and higher stages of development to comprehend and engage differences.

When it comes to diversity it seems reasonable to include both differences among individuals, as well as among and within groups or systems. Applying it to both is essential to an integral approach. This can refer to virtually any kind of difference. In a recent book by the University of Virginia’s Martin N. Davidson (2011) the author and his collaborators argue that the focus on diversity in business and organizations has been too narrow. It has meant managing diversity. In the first place achieving diversity has been sought to meet the requirements of laws, regulations and even social values. It has meant hiring people of different races, breaking glass ceilings, even reflecting the racial, and ethnic characteristics of the community or society. Consequently, promoting diversity within organizations has been a task, a challenge to be met in the name of values of equity and social justice, as well as an economic necessity.

Davidson goes on to argue that this approach does have the potential to bring people of different perspectives and identities to work effectively together. But it is not enough. Rather, it is important for the management of a company to gain clarity about what are the elements of diversity required to foster productivity, innovation and an expanding market place for goods and services. Then they must leverage these. He is clear, however, that this does not mean backing away from commitments to human and social values. He shifts from focusing on diversity to focusing on differences in the creation of organizational cultures in which values of respect, equity and social justice are emphasized. Ruth Benedict (1934) found,

Societies where non-aggression is conspicuous have social orders in which the individual by and at the same time serves his own advantage and that of the group. . . Non-aggression occurs in these societies not because people are unselfish and put social obligations above personal desires, but when social arrangements make these two identical (148).

Effectively working with differences even goes beyond this. According to Davidson,

Organizations that truly leverage differences cultivate the capability to engage with and learn from diverse stakeholders, including employees, customers, partners, and communities. They use what they learn to explore how they can do the work of their organization more effectively. They are able to apply lessons of difference to domains as wide-ranging as customer engagement, operational procedures, and alliances with community resources (9-10).

In an integral approach we bring attention to variables that go beyond the traditional ways of dealing with diversity into a more inclusive mental map of the dynamics of working with differences in human systems. It involves attention to individual development and behavior, organizational cultures and organizational systems in relation to socio-eco-political systems in which they operate. We recognize the extraordinary level of complexity in which connectivity and communications can be conducted and disrupted in moments. An integral approach enhances attention to the variables in this complexity. Maslow (1971) noted,

- Human beings have an innate tendency to move toward higher levels of health, creativity, and self-fulfillment.

- Neurosis may be regarded as a blockage of the tendency toward self-actualization.

- The evolution of a synergistic society is a natural and essential process. This is a society in which all individuals may reach a high level of self-development, without restricting each other’s freedom.

- Business efficiency and personal growth can go well along together. In fact, the self-actualization process leads an individual to high levels of efficiency (xxxv).

Diversity’s relationship with integral leadership, then, can be understood as the role of diversity in an integral practice, development and understanding of leadership. It concerns how those who are leading attract and integrate differences for the purposes they seek. Of course, the answer to this exploration will be: it depends. How it relates to and depends on integral variables can be explored in any ideographical context. It can also be understood as how individuals perform in leader roles to address and/or leverage diversity to achieve specific purposes. The dynamics of differences among individuals can be addressed at the levels of individual psychology, social psychology, group dynamics, cultures and systems; although in social group culture and systemic dimensions it reaches a level of complexity befitting a more collective, dialogical view (Linell 2009). Such a view would look at influences in sense and meaning making as a two- way street on which there are complex dynamics.

Engaging differences describes, in part, activities that we associate with terms such as leader and leadership. Already I have used several terms that suggest there are nuances to their meaning, as well as to their manifestation, in social systems. Diversity and differences, leader and leadership–does each pair of terms refer to the same things or some things quite different? Our answers to that question will lead us to potentially quite varied ideas about what the terms mean and how we will recognize their manifestation in a variety of contexts. Such contexts might include our own personal reflections, our interpersonal relationships at work and at play, our involvement in group and organizational activities, as well as our relationships to large social, economic and political systems. It is no wonder that, without this understanding, there can be 1500 definitions of leadership. A fundamental point of this paper is that definitions of terms must be contextual. Having distinctions such as those I will propose here provides us the lens through which we can examine an occurrence in which individuals lead, systems perform and change occurs while differences are engaged and leveraged.

Leadership

Leadership, as a field of study that is both academic and popular, is filled with differences in models and theory, on the one hand, and advice for development and practice, on the other. Kouzes and Posner (1987) offered five key practices to be effective as leaders, including elements that are echoed in many writing since. For example, inspiring a shared vision, which challenges us to look at the relationship between leadership and diversity. It suggests, as have many others, that leading is about forging some sort of agreement, some sort of solidarity, building upon something that is shared, presumably in a context where such sharing is challenged by the existence of differences. Inspiring a diverse group of individuals makes the possibility of inspiration less certain and more fragmented in the cultural fabric of the group.

It is a full circle of relationships we find when trying to sort through the connections among aspects of diversity and of leadership. And yet, how clear is this discussion in the literature to this point? As is common in publications about leadership in particular, we bring a collection of concepts to bear even when we are not clear to what we are referring. In 1989, Joseph Rost (1991) began a study of this ambiguity in which he concluded that all of the definitions in the literature on leadership to that time could be summed up as “Leadership is great men and women with certain preferred traits influencing followers to do what the leaders wish in order to achieve group or organizational goals that reflect excellence defined as some kind of higher order effectiveness” (p. 91). He then suggested an alternative. “Leadership is an influence relationship among leaders and followers who intend real changes that reflect their mutual purposes” (p. 102).

More recent definitions have not gone far beyond this. There have been shifts to “scientific” definitions such as, “leadership in complex systems takes place during interactions among agents when those interactions lead to changes in the way agents expect to relate to one another in the future.” (Hazy, Goldstein and Lichtenstein 2007, 7). Furthermore, “Effective leadership occurs when the changes observed in one or more agents (i.e., leadership) leads to increased fitness for those systems in its environment” (7). One utility of definitions such as this is that it makes very clear that leadership is about individuals, relationships and context (complex systems). It also suggests that success or failure is the product of the various relationships among these variables over time. Thus, this approach adds to that offered by Rost. We can pick at this definitional approach a bit: (1) the assumption that changes in future relationships among agents is due to leadership without concern for changes in life conditions, or (2) that leadership that does not increase fitness must be something else other than leadership. Like most approaches to definition, this one—like Rost’s—is true, but partial.

From the highly respected Center for Creative Leadership we find a recent book on boundary spanning leadership (Ernst and Chrobot-Mason, 2011, p. 5): “the ability to create direction, alignment, and commitment across boundaries in service of a higher vision or goal.” Here the emphasis shifts from the system to individual competency or ability. That, of course, leaves out context, at least at the level of definition, albeit this work is specifically about leading at the interface of contextual boundaries.

Rost’s work was an attempt to meet the challenge that “No one has presented an articulated school of leadership that integrates our understanding of leadership into a holistic framework” (9). His may be the first academic effort toward an integrated theory of leadership. While he did his work without apparent awareness of integral theory (even in its rudimentary forms existing at the time of his writing), he understood an analysis and approach that attended to individual and collective, and the diverse sets of relationships possible among them. He understood the importance of context for any attempt at definition. Here I take this a step further and suggest that every definition of leadership is by its nature contextual and is true, but partial. Each has something of value to offer in the practice, development and study of leadership. Rather than focusing on a definition, then, we might consider how we distinguish among terms in order to shape contextual definitions. Distinctions are our way of differentiating meaning in different and changing contexts.

Ladkin (2010, 1) suggests that we need to change the questions we ask from “What is leadership?” to “How do we understand the phenomena of leadership?” This is very much a step in the right direction. Leadership, however we construe the term, is going to appear and be different in a tribal setting, a kingdom, a church, a business or a community. Even within such broad categories, there will be differences in the expectations and practices of individuals in those human systems.

The following account may help ground this discussion of cultures in business.

In the contemporary business environment leadership will not be the same among innovation teams or among corporate executive management committees. As an example, I recently interviewed the CEO (let’s call him David) of a marketing and advertising firm that has been thriving in spite of the economic turmoil that has faced all of us in the early years of the twenty-first century. He approaches leading his company with a firm belief in building a culture of stakeholder support both within his company and in relation to their clients. He recounted an example of how holding such a culture in the contemporary business environment can be in conflict with the values and cultures of client companies.

His agency was in a competition to secure the business of a division of a large Fortune 500 company. In the early stages of the competition he discovered that the client CEO had his staff checking up on the activities of the agency’s personnel as they were working on their assignments. David and his staff found this to be intrusive and contrary to the values and practices of commitment and trust they sought to foster in relation to clients. David went to the CEO and told him his agency was withdrawing from the competition because of the culture clash under his approach to leading. The CEO was shocked. No one had ever talked to him like that before! As a consequence, the CEO contracted with another agency. Within 90 days the relationship between the CEO and that agency collapsed and that contract was terminated.

Two different types of business with two very different CEOs and two very different organizational cultures were being led in two very different ways. How do we explain such differences? We may do so by understanding what was at play on the part of the individuals in the leader roles, how cultural variability contributed, and how organizational, industry, socio-economic and political context may have played a role. Were relationships different following this episode? Were the systems more fit? Well, we don’t know about how things went with the larger company. However, the boost to morale and the strength of relationships within the agency was palpable and overt.

Clearly each CEO brought different assumptions, beliefs and practices to the use of behaviors they believed were appropriate in their business context. Could we define leadership as the same in each context? I maintain that would not be useful. Rather, we need to develop clarity about the context of each to understand their practices of leading, as well as the complex phenomena of leadership in order to determine such things a what effective leading will look like, what cultural and systemic elements influence effectiveness, and what individual and organizational development challenges are indicated in these different organizational systems.

Definitions and Distinctions

Some one (sic) has remarked that there is a latent tendency in the human mind to define a thing in order to avoid the necessity of understanding it.

—John Latané (1907) America as a World Power, 1897-1907, p. 255.

Making distinctions (Volckmann 2010) among terms, before defining them in particular contexts, offers a strategy in our sense and meaning making approaches when considering any complex phenomenon. Consider that the key terms in the title of this chapter all suffer from ambiguity of meaning in that there is little specific agreement on what the terms signify. But first there is the matter of the term distinction. My usage of the term relates to these categories:

- Differences and contrasts between two things, and

- Dividing things into different groups based on their attributes.

Thus, by making distinctions we are creating criteria with which to evaluate or describe phenomena in a particular context. We are laying the foundation for what questions to ask, what it is we need to look at and look for. By being clearer about the distinctions we use we can be more aware and articulate about how we comprehend phenomena related to leadership in human systems. This comes about because we are beginning to use words as lenses through which to engage in sense and meaning making. They are frameworks for understanding, as opposed to imposing meaning.

This approach is re-enforced by a theory recently proposed by MIT’s Piantadosi, Tily and Gibson (2012):

In a system optimized for conveying information between a speaker and a listener. . . each word would have just one meaning, eliminating any chance of confusion or misunderstanding. Now, a group of MIT cognitive scientists has turned this idea on its head. In a new theory, they claim that ambiguity actually makes language more efficient, by allowing for the reuse of short, efficient sounds that listeners can easily disambiguate with the help of context.

‘Various people have said that ambiguity is a problem for communication,’ says Ted Gibson, an MIT professor of cognitive science and senior author of a paper describing the research to appear in the journal Cognition. ‘But once we understand that context disambiguates, then ambiguity is not a problem – it’s something you can take advantage of, because you can reuse easy [words] in different contexts over and over again.’

The relevance of these observations for our discussion of diversity and leadership is that by making distinctions among terms we maintain ambiguity about the specific meaning of each. If the proposition that distinctions must precede definition proves useful, then we can use distinctions for guiding what we look for in specific contexts. When we use these distinctions in a specific context we are able to reduce the ambiguity and clarify meaning. As an example if we use the term leader to refer to an individual in the context of an executive team in a global business we could identify the intentions and worldview of that individual, the person’s behaviors, her relationship with the culture of the team and those aspects of the team system (structure, processes, technology) that she uses to leverage her relationships with stakeholders and achieve change. We could then define leader in that context. The definition we create would most likely be somewhat different if we were talking about the leader of an Army squad or a troop of girl scouts. Each would offer variations in meaning in defining the expectations of stakeholders and, hence, the role of leader. At that point we would also have a systematic way of comparing and contrasting contextual factors, individual and collective, structure and process, to build out distinctions as useful meta concepts. These meta concepts refine our distinctions.

Distinctions and Leadership

Here is a set of distinctions intended to serve us. They are concepts we use in seeking to understand what is important for us to attend to, how we engage with others and how we seek to move together collectively in designing and attended to the life conditions that provide us with feedback about the well being of ourselves and others. What if we were to use terms in these three ways?

- Leader–a role in a system, that is, a set of expectations held by members of a society, community or organization about desired and appropriate behaviors and qualities of individuals who temporarily occupy the role. For example, members of an organization would hold that leaders are knowledgeable or have a clear understanding of a current situation. Thus, in looking at the role of leader we would want to know what are the expectations held by the stakeholders in that role. Stakeholder is a term referring to any individual who places a value on a role—a role occupied by an individual or a collective (Mitroff, 1983, 5). It could be argued that there are stakeholders who will be impacted by someone filling that role, but unless they place a value on that impact it is probably not useful to include them, except in a negative sense, i.e., their expectation of individuals who occupy the role is that they will not be impacted by what those individuals do.

Notice that it is highly unlikely that all stakeholders will have the same expectations of the role. This has been observed in discussions of role ambiguity, role complexity and role conflict (Katz and Kahn 1978). It is not surprising that individuals who fill a leader role in complex human systems experience a great deal of stress. Employees may have the expectation that their jobs will be protected. Stockholders may expect maximum quarterly return on investment. Competitors may expect stealth and obfuscation. Peers and associates may expect inclusion and openness. The result is that anyone stepping into such a role “be and do” in such a way as to garner sufficient support to facilitate some shift in the state of the culture, the systems and the relationships within them—whatever the outcomes supported by stakeholders. Often, this is a difficult thing to accomplish. Hence, we have an expression like, “Politicians! We swear them in and cuss them out!”

There has been considerable research on role ambiguity and complexity in organizations, including the impact leaders have on performance or on innovation. Tang and Chang (2010) have provided a useful study and bibliography of the impact on employee creativity for those wishing to explore this further.

As Joseph Rost (1993) noted, no one is in a leader role 24/7. Consequently, treating the term “leader” as designating a role makes more sense than using it as a label for an individual. If we were to observe a system as though taking a snapshot or a short YouTube video we might see an individual occupying that role for a short time. Extend the time so that we have a full-length movie and we will inevitably see individuals moving in and out of leader roles. In executive teams faced with the extraordinary complexity of the global business environment today, no one individual, CEO or otherwise, can manage the information and complex set of variables to lead on all topics. Executive leading is increasingly a dynamic team process in which the role shifts from one individual to another.

When we bring an integral theory framework to the subject of roles, then, we are looking at the complex web of relationships expressed as expectations. Here is where the literature on leadership as a relationship between “leader” and “follower” is relevant. Gardner (2004) among others has pointed out that there are no leaders without followers. In other words, there is no leader role without a follower role. I would reframe that as there is no one leading without someone following. Richard Barrett (2010), an international consultant who has been drawing on integral theory and adult development stage theory, challenges this idea by expanding the notion of leading (leadership in his terms) to self-leadership; in that case the person leading and following is the same person.

In recent years, particularly since Lee (1983) and more prominently the work of Kellerman (2008) and Riggio et al (2008), there has been growing attention to leadership as a relationship between those who follow and those who lead, including the ways individuals who follow shape those who lead. As suggested above, I think the focus on followers is too narrow. We need to consider all stakeholders to understand the nature of the leader role and to understand how individuals fill those roles effectively. Equally important is attending to the nature of culture, systems, processes, technologies and the like. All of these contribute in a dialogical process with the individual in shaping sense and meaning making generally, and particularly in relation to the leader role.

2. Leading—the activities of individuals temporarily occupying the role of leader. Here is where much of the popular and academic leadership literature tends to focus. When researchers and theorists talk about what a leader does, it is a description of an individual in the role of leader and the behaviors of that individual that relate to that role. For example, the suggestion that leaders articulate and hold a vision is an indication of a behavior. So is being authentic (Avolio 2011) or being a servant (Greenleaf 1977). Underlying these are the perspectives and intentions that individuals bring. It may seem as if there is little difference between the role and the behaviors, because we are more likely to identify individuals as having filled the role if they exhibit the corresponding behaviors. But there is.

In addition to the behaviors we can observe, there are the intentions, beliefs, assumptions, values, worldview and more that we cannot literally see. These play a critical role in how individuals behave and how they are perceived by others. Do they listen? Do they consider what they hear in how they behave? Do they see the issues clearly? Do they want they same results as the rest of us (even when such agreement may be fragile and temporary)? Can they connect through the culture to the rest of us? Are they interacting with the structures, roles, systems and processes essential for realizing aspirations in this context? Leading, like living, is a complex business.

Most of the programs labeled leader or leadership development are, in fact, designed to educate and train individuals. Literally, they are individual development in the contexts of teams and organizations that hope to groom those individuals for current and/or future leader roles. The Center for Creative Leadership (2012) is a major provider of such programs. In fact, they provide a Leader Development Roadmap to guide individuals in choosing their programs. Their categories remind us of the work of Richard Barrett (2011): leading self, leading others, leading managers, leading the function and leading the organization. Notice the choice of terms here: leading! That is the use of language that I think will help all get clarity about leader development: the individual.

Bruce Avolio (2011) sees a merging of leadership development and personal development. This influential scholar was the Director of the Gallup Leadership Institute at the University of Nebraska before becoming the Executive Director of the Center for Leadership Development and Strategic Thinking at the University of Washington. He recently published the Second Edition of his best known book on the subject in which he captures a number of the things he has learned in the decade between editions. He notes,

In all the discussions I had about leadership. . . one issue repeatedly came up. The issue involves discussing leadership as a systemic process, as a person, or as a combination of both. . . [As] a system and process, we can explore the context in which leadership occurs, the characteristics of followers, the timing of events, the history in which leadership is embedded, and so forth, When discussed as persons, we get into names, personality characteristics, values…experience, how intelligence plays a role in successes and failures, and so forth (vii).

Clearly, this is an indication that leadership scholars (Day et al 2009; Ladkin, 2010) are seeking ways to include both. As an observer of these scholars for many years, I have seen them struggling to find that integrative approach that allows for the nature of the system (and culture), the individual and their actions, process and time. You can find such approaches in other recent efforts (Goethals and Sorenson, 2006; Harvey and Riggio (2011), as well as in the formation of centers or institutes of integrative leadership such as one found at the University of Minnesota (Crosby 2008). By distinguishing among the terms in the way I am suggesting (albeit there may be superior alternatives) we take a step in the direction of such integration. In fact, the concept of leadership considered integrally offers a theoretical and even metatheoretical approach that may meet the needs of these scholars.

3. Leadership—involves the role (leader), the behaviors and worldviews—including beliefs, intentions and the like—(leading) and the context (systems and culture). But it is a context that goes beyond our notions of situation and situational management or leadership (Hersey and Blanchard 1969). It is a context that includes culture, as well as systems, processes, technologies and so on. Thus, the term leadership refers to the gestalt of bio-psycho-social (Beck and Cowan 1996) phenomena in which many variables are played out in the service of accomplishing something, even if that is maintaining the status quo in the face of challenges.

Using the term leadership in this way very much supports the increasing realization that effectively leading is the result of factors that go beyond “great man” or trait theories. James O’Toole (2001) noted the relevance of organizational systems for effectively leading. Through research conducted in collaboration with Booz•Allen & Hamilton and the University of Southern California’s Center for Effective Organizations for the World Economic Forum, they found that systems enabled effective leading. They included attention to goal setting and planning, risk management, communications and recruiting systems within organizations. We can certainly add more, such as reward systems, scaffolding learning for individuals and collectively, and scenario development processes (Volckmann and Belamy, 2010).

By continuing to use terms such as leading, leader and leadership as though they mean the same thing, we shall continue the confusion that has existed in not only the academic view of leading-leader-leadership, but in developing individuals to perform in leader roles and in developing human systems to support effective leading. This is already being recognized as a need in the study of leadership and in the field of leader development.

Distinctions and Development

In a phenomenological approach to the study of leadership, Ladkin (2010) notes,

This book is primarily concerned with ‘leadership’, rather than ’leaders’. Leadership is seen as a collective process, encompassing both those who would be known as ‘leaders’ and those who would be known as ‘followers’…I assume that these are not static labels and that leadership can readily pass between them so that leaders can act as followers and followers can act as leaders in certain circumstances. The experience of leadership is also assumed to emerge from particular social and historical contexts (p. 11).

A difference between Ladkin’s approach and what I am suggesting here is that for her leadership is a collective phenomenon and I am suggesting that it is the conjunction of individual and collective phenomena.

David V. Day and his coauthors (2009) also make a distinction between leader and leadership. Here their focus is on developing the capabilities of individuals to step into leader roles. They distinguish the two as follows:

Leader development: Enhancing the capacity of individuals to engage successfully in the leadership tasks and roles in an organization, focusing on developing individual knowledge, skills, and abilities related to leadership. . . .

Leadership development: Enhancing the capacity of teams and organizations to engage successfully in leadership tasks, focusing on building the networked connections among members that develop leadership capacity (299).

In their case they are still not distinguishing clearly among leading-leader-leadership, but it is a strong move in the right direction. By using these distinctions in relation to development we can examine the implications of the developmental methodologies we choose. For example, preparing individuals to lead, that is to step into (and out of) leader roles, would entail skill development, awareness development, approaches to clarifying intentions and ethics, congruency of behaviors and skill application in different contexts, and consciousness development. The training and self-help fields are full of these developmental approaches; the challenge is to assure a set and methods that will best serve each individual.

By contrast, if we are concerned with leadership development, we not only must attend to individual development, but cultural and social development in the organization that results in various ways to define the role of leader. There is more. It would also require attending to the development of systems in the organization and in its interface with stakeholders and other systems. There would be an ongoing process of aligning these with what is required for individuals to successfully conduct the leader role in changing and often ambiguous circumstances.

I would suggest that the three-part distinction I am offering dissolves the confusion about the use and utility of other terms, such as roles, systems and networks, and culture. It also calls into question the categories of management and leader/leadership development on which corporations spend billions of dollars every year. In some circumstances, productivity management skills, often thought of as a management skill, is also essential for effective performance in a leader role. Having clarity about the relevance and importance of skills and knowledge in different contexts would help to clarify what is truly valuable about development for individuals in leader roles.

Distinctions and Diversity

Gregory and Rafanti (2010) have laid a solid foundation to exploring what diversity is. For one, they distinguish diversity from difference “from the dominant norm” (1014), which treats the former as a far more complex term, while the latter is reductionist. To redress the focus on categories they argue for attending to diversity dynamics—moving from the snapshot to the movie. They posit a maturation process achieved through transformational learning, which they prescribe for those in leader roles. They can, therefore, leverage diversity to foster broader development and the achievement of generative objectives in human systems.

In reflecting on types of diversity and the distinctions related to diversity, they draw on the work of Mary Gentile (1995) who extended the focus on demographics to “ways of thinking”. Gregory and Rafanti then point to the importance of shifting the way we think about diversity to a post-conventional maturity (2009). Their work is an important contribution, particularly for their development of a more dynamic way of comprehending diversity.

Diversity is valued. There is a growing literature on diversity and its importance for creativity and innovation in groups and organizations. This perspective also has a foundation in the natural sciences. This from S. J. Gates, Jr., the J. S. Toll Professor of Physics and Center for Particle and String Theory Director at the University of Maryland, College Park:

It is almost universally accepted that diversity is of great importance in biological realms. The genetic diversity of an organism or group of organisms is almost always found to enhance long term prospects for survival. A diverse genetic pool is the reserve from which biological systems draw in order to adapt to changing environments. Diversity is often associated with enhanced levels of vigor and performance.” (Gates n.d.).

In effect, diversity in the expanded sense of differences is an essential ingredient for our healthy existence as biological beings. It is the source of our adaptability and lends an important ingredient to any exploration of leading, the leader role and leadership. In the life of a system, diversity provides the potential for generative new manifestations of leading as individual performers, as well as leadership as a complex social phenomenon.

Terms related to leadership and to diversity will have varying definitions based on integral variables, including “quadrants,” lines, levels of development and type. Through an integral lens we can see that individuals (and cultures) at any given point in time are experiencing diversity according to the following:

- Lines of development are akin to the idea of multiple intelligences (Howard Gardner). These lines can include cognitive, emotional, kinesthetic, ethical and other intelligences, including the amorphous spiritual. In fact, each of these may be broken down into subsets, thus multiplying the number of lines of development we must consider in mapping human diversity. An example is the The Hay Groups’ Emotional Competency Inventory, a 360° assessment of emotional intelligences based on the work of Goleman et al (2002). At my last count there were sixteen variables related to self-awareness, self-management, social-awareness and relationship management. The emotional line of development includes these and is even more complex when we add in other psychological variables involving memory, neuroses and the like.

- Stages of development provide suggestive indicators of the evolution of individuals and cultures. Each stage model provides a map that suggests the evolution of worldviews, ego development, action logic, moral and ethical development, and so on. There is a lot to learn about these stage models in terms of their dynamics over time. A primary question would be related to the factors that stimulate development, the pace of development, what recidivism occurs under what life conditions and so on. As a mapping tool for diversity the stage models provide a wealth of lenses. In addition, when the learning from these models is used in individual development for leader roles, how can they best be used generatively for learning and application? NOTE:There is considerable resistance to stage theories of adult development. On the surface they may seem elitist or over-simplistic. They are neither (although some people may try to use them that way ). There are several factors to keep in mind about how stages show up in individuals and systems. (1) Linearity is optional; we can move upward and downward in the hierarchy of stages; (2) stages are not boxes; we are not contained by a stage, we contain the stages; (3) lateral development within stages is at least as relevant as vertical development and far more common since it involves learning and experience (and is even necessary for movement vertically; and (4) multiple stages coexist; many stages operate simultaneously within each of us and every human system. With these propositions in mind we can appreciate the richness and challenges of stage as a variable in our integral analyses.

- Type is another one of those variables that be used to map the qualities of diversity within and among us (over time). Here is where we find the demographic variables of sex, race, age, nationality, even height and weight. In addition we have type maps based on lines of development, e.g., the Myers-Briggs Typology Inventory draws on Carl Jung’s model of individual psychology and includes variables (often misunderstood and misapplied) like sensation, intuition, thinking, feeling, introversion and extraversion. Some of the stage models have been used to create maps and assessments of different approaches to leadership. An example is how Susann Cook-Greuter has built upon Jane Loevinger’s approach to create a Sentence Completetion Test that includes assessment of Post-Autonomous Ego Development (Cook-Greuter 2010) and how her assessment has been modified by Torbert and Rooke into the Leadership Development Profile (2007). It is in these first three realms that Davidson’s (2011) work is most relevant.

- States is a snapshot variable in out mapping of diversity A state occurs for a brief amount of time, as though one could see it in a still photograph. Virtually any of the factors included here and yet to be offered can vary for the individual and in a culture at any moment, depending on life conditions and quality of being and doing in the world. For example, if I receive notification that I owe the IRS a large sum of money, this is likely to impact my emotional and cognitive and other lines of development, at least for a moment or two, and perhaps for a longer period of time, depending on how stressful that news is. Nevertheless, this would be a state experience.

There are other variables that can be considered in diversity. What follows has been suggested by Mark Edwards (2010) in quite another context and may not include all he had in mind.

- Perspective is a term that has taken on considerable importance in Wilberian integral theory, but is not included in the basic AQAL model. A basic way to appreciate perspective is to consider any idea or event from first person, second person and third person positions. I used to teach graduate courses to police officers during the days when the Federal Government was betting that a more effective force in dealing with diversity would be a better-educated force. One of the things I learned from officers I taught was that in a crime or accident situation, they did not like to have too many witnesses, because this would result in different accounts of the events. By having sometimes significantly different accounts or descriptions, it was difficult to present testimony that would result in a conviction of a perpetrator. Nevertheless, in understanding complex phenomena (including some crimes) it is important to have the ability to shift perspective (Joiner and Josephs, 2007). Ron Heifitz (2002) has suggested a narrower notion of perspective through his suggestion to “get into the balcony” for a shift to higher level perspective. Diversity, then, can include the differing capacities to shift perspectives.

- Power distribution seems inherently variable in any social system, particularly when there are multiple foundations or sources of power and multiple ways in which it can manifest. Diversity can be considered in terms of differential access to power and its symbols, as well as how power is used personally, interpersonally and systemically. If we add to this the idea that there are multiple sources of power, the level of complexity of this lens multiplies. Power can rest upon one’s formal role in a system, e.g., the “boss,” or on the basis of physical power, e.g., the “bully.” And then there is the observation that information is power. There are a myriad of role-based and other variables from which power is derived.

The following is a continuation of the list of lenses suggested by Edwards (2010, 130):

Holarchy: a form of systemic structuring that includes governance;

Bipolar: a lens in which alternatives are viewed as being the ends of a continuum;

Cyclic: a process focus that goes through several stages only to return to its original stage as in relation to development change, evolution, learning–the spiral is a developmental cycle;

Relational: an interactive process focus;

Standpoint: a perspective that can reflect all aspects of the observer (or lens user), including worldview and physical relationship to that which is being observed; and

Multimorphic: various combinations of the above lenses.

This entire exploration of variables related to diversity (and differences) represents great potential in sense and meaning making through analyses and theory building. Every individual and every culture of every social system can be viewed through these lenses and their combinations. If we are to consider diversity as a variable in understanding social phenomena, including leadership, there is a potential significance for each of these. Any leadership occurrence may involve one or all of these diverse variables. Specifying the distinctions among the characteristics of diversity and differences in a given context will lead to greater clarity about its relationship to leadership, as well as other organizational and social phenomena. It will also lead to context specific definitions.

With an integrally expanded view of variables that contribute to our notions and experience of diversity we can set the stage for exploring how diversity relates to leading, the leader role and leadership. What we will find is a very high level of complexity. Furthermore, ignoring these variables has significant implications for both the study and practice of leader role definition and leadership, as well as development of individuals to fill leader roles

Leadership Studies

I must confess that I do not know of any research that has been done that explores the relationship between leading, leader and leadership in the face of this complex view of diversity. However, there is a variety of literature linking the concept of diversity to one of these distinctions or more. Michael D. Mumford, upon concluding his six-year role as editor of Leadership Quarterly offered four objectives of this major publication in the field:

1) International contributors;

2) Diversity of perspectives;

3) Quality of method; and

4) Diversity of content.

Clearly, this represents diversity as significant in the study of leadership, cultural, content and perspectives: “a variety of perspectives on leadership– perspectives reflected in different fields, or disciplines, of scholarly work” (Mumford 2011, 3). He goes on to note how the variety of research and articles represented in the journal are more and more diverse to the point that other fields of study (e.g., social psychology) are producing more diverse contributions to the field. The scientific focus of the field is emphasized,

leadership is a phenomenon that operates at multiple levels of analysis (Yammarino & Dansereau, 2008)–individual (e.g., Johnson, 2008), dyadic (e.g., Golden & Veiga, 2008), group/team (e.g., Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2006), organizational (e.g., Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007), and societal (e.g., Seyranian & Bligh, 2008). Second, five methods are commonly applied in studies of leadership–1) survey studies (e.g., Rowold & Heinitz, 2007); 2) field investigations (e.g., Norman, Avolio, & Luthans, 2010); 3) experimental (e.g., Marcy & Mumford, 2010); 4) historiometric (e.g., Bligh & Hess, 2007); and 5) quantitative (e.g., Ladkin, 2008). . . . The Leadership Quarterly regularly publishes articles focused on all five of these levels of analysis. Studies have examined the role of leaders in shaping team norms (Taggar & Ellis, 2007). Other studies have examined the movement of women into executive, organizational level, leadership positions. The gap that has existed, and may continue to exist, in the literature has been the examination of multi-level influences on leadership (Dionne & Dionne, 2008; Mumford, Antes, Caughron, & Friedrich, 2008). Not only should multi-level effects be examined in many studies of leadership, using techniques such as hierarchical modeling and within and between analysis, it is important to bear in mind that multi-level concepts have noteworthy implications for the nature of the measures we apply in studies of leadership (Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, 2008) (Mumford, 4).

All of this is presented in the context of a sigh of relief, a sign of new horizons, fostered by an end to the search for a general theory of leadership. “What has become clear is that the day of the global theory for leader success is over” (Mumford, 6). While this is a welcome acknowledgement of the importance of context for leadership success at no point is there attention given to the need to integrate the diversity he is celebrating.

So what do we make of this from an integral point of view? Diversity in some of its senses is being valued: diversity of culture, perspective, level of analysis and so on–both the subjects and the objects of research. There is a welcoming of the many disciplines that contribute to the study of leadership, but there is no observable valuing of the integration of the perspectives. There is a welcoming of diversity of study within a field of “clear boundaries,” and here is an issue from an integral perspective. Boundaries are useful and relevant in conducting certain types of research, but nowhere have I found a delineation of the boundaries of the field of leadership studies that incorporates all of the elements of integral and of diversity presented above. Boundaries may be ideographically useful, but integratively limiting (Wilber 1979).

Studying Leadership and Diversity

What is the nature of the study of the relationship between leadership and diversity? In what follows I offer some examples to represent the range of material and conclusions drawn from them. Where possible, I will identify integrally valuable contributions.

Dreachlins (1996) has explored managing diversity in healthcare. Here the focus is on the manager (not the leader) role in relation to type variables of diversity in healthcare environments. Nevertheless, her extensive work in this arena provides useful data that can be considered in a more integral exploration using the distinctions offered here. The implications of boundaries in organizations and their effective management (Dreachlins, Korbinski and Passens 1994) calls attention to the systemic variables within which diversity is played out. Leadership is considered as an aspect of exchange, of incorporating chaos into the order of the organization. Context, perspective and continuity they consider to be essential “states” required for engaging the challenges of the organization.

Another realm of application relates to spirituality (and religion) and the management of diversity, (Hicks, 2002): “Diversity of spiritual and religious preferences in the workplace present challenges for leadership. First, this analysis suggests expanding leadership approaches to diversity and conflict in order to attend to religiously based conflict (391)” Hicks references the work of Heifitz (1994) on the value of conflict for creativity. He sees the role of the leader as orchestrating the interplay of diverse aspects of the organization’s members to support the achievement of goals.

Chen and van Velsor (1996) expand the consideration of diversity to the globalization of organizations and the implications for leadership. We even find the term diversity leadership, which I understand to be the label of a function of leading, rather than a style. With globalization the integration of diversity in organizational operations and aspirations increasingly involves working with many aspects of diversity.

Understanding the meaning and implications of diversity is at the core of the difficulty inherent in successful globalization and is key to some of the toughest performance and development issues with which people struggle in downsizing or otherwise rapidly changing environments (Chen and van Velsor 285).

The focus on diversity relates to demographic and cultural variables. Nevertheless, their work is relevant in that they distinguish the approaches of leadership and diversity researchers on the relationships between the concepts. They note that while leadership theorists focus on diversity as a variable within leadership frameworks, the focus of diversity theorists is to challenge the assumptions of leadership theory in the context of diversity (286). Furthermore, the latter tend to focus on identity issues that from an integral point of view would involve UL, lines, stages, states and types. The former focus is on intrapersonal (UL) and interpersonal which can involve multiple quadrants and other variables.

While both approaches attend to power issues, leadership studies tend to depoliticize this, while diversity scholars emphasize it. Also, the study of diversity in organizations directs the focus more on the followers in relation to the leader role and the dynamics of leadership. This has implications for developing and understanding distributed leadership and its use in the face of complexity and challenges of innovation. Chen and van Velsor’s findings with regard to leader development recognize distinctions of requirements according to type (male vs. female) and other elements of traditional elements of diversity. Work such as this does lay a useful foundation for including diversity in the study of leadership, but from an integral point of view the distinctions of types of diversity are narrow and the number of integral variables attended to are limiting.

It is of interest to note that John Rowan, a British Psychotherapist and appreciator of integral theory, commented on Wilber’s inclusion of types in his integral map, AQAL. He appreciates quadrants, lines, levels, but says,

[T]ypes is not the same thing at all. It is a completely different concept, which Wilber treats in quite a different way. The only example he gives of a type is male and female, but he suggests that there may be many types, such as for example psychological types (2007, 11-15).

The snag is that types are one level concepts–what Wilber often calls flatland. They can be found at any level, but they do not have levels within themselves. They are much the same wherever found. There are no levels of malehood or femalehood. There is just male and female. In fact, as we know from much recent research, there are all sorts of variations in gender identity . . . But they are all, without exception, one level concepts. There is no concept of hierarchy, or holarchy, in any of this.

So how does this impact the discussion of diversity and leadership? The distinctions discussed herein (and others) would provide a framework for exploring such a question. Using such distinctions shapes how we understand differences from different stages of development. It is likely that those with more complex (not necessarily better in any given context) cognitive development of worldviews will have varying ways of comprehending and appreciating differences This also suggests the question of how do differences manifest at different stages of development? Raising questions such as these provide a benefit of including perspectives from adult development psychology and from integral approaches to theory and analysis.

The field of leadership studies is beginning to offer analyses that are very much in keeping with this discussion. Nancy DiTomaso and Robert Hooijberg provide an overview of the literature relating diversity and leadership. They divide the diversity literature into four parts:

First, we discuss the management literature on diversity as it has been conceptualized so far, that is, the literature on interpersonal and intergroup interaction, combined with the practice oriented work on human resources and employment law. Then we discuss three other bodies of literature that are clearly relevant to diversity, but which have not typically been included in the diversity literature in management. These literatures include: recent management literature on organizational change which has significant implications for the study of diversity; literature from the social and behavioral sciences which is about diversity in a broad sense; and the literature on the ethics and morality of multiculturalism and diversity (163).

I would argue that theirs is an integrative approach, if not formally integral, but it is dialogical:

Our model assumes that the attitudes, values, beliefs, and hence, behaviors, of individuals are socially constructed within a context of group and intergroup relations and that people act through social, political, and economic institutions that create, embed, and reproduce the inequality among people which we then call diversity (164).

Here we have the Upper Left quadrant represented by attitudes, values and beliefs; the Upper Right by behaviors, all of which arise dialogically through culture and systems in which diversity in its broadest sense is represented. It is comprehension such as their work represents that lays a foundation for a metatheoretical, including integral, scope of understanding. But where this analysis begins to more closely touch the world of integral theory is in the discussion of ethical and moral diversity. They point out the relationship between national identity, language and religion as common cultural traditions. So, in politics, “What this means, among other things, is that political power is supported, in part, by moral interpretations of the rights of leaders to lead” (176). They continue,

There are two important implications to the diversity of morality and ethics. The first is that in our attempts to understand each other, we may be using a frame of reference which does not fit with that of others. The second is that we tend to react emotionally, usually with anger or dismay, when people appear to violate our sense of morality. As a consequence, we tend to treat them as immoral, and hence, as outsiders (177).

It is in the second sense that we are encouraged to turn to the “stage” aspect of integral and the importance of leading, particularly a more aware and conscious leading, to address the diversity among us, whether in societies or organizations. The first implication cited by DiTomaso and Hooijberg encourages us to turn to integral theory for insight and direction in relation to diversity. Their discussion pertains to all four quadrants of Wilber’s map and it pertains to the question of stages or levels of development. They see systems thinking involving the capacity to “see wholes” as an essential aspect of this enterprise, an approach that can be extended to integral approaches.

While by no means a survey of the literature in the field of leadership and diversity, in the above examples, we find the interests and the challenges that call forth attending to a more general theoretical approach that can integrate our comprehension of leadership and diversity. An integral framework offers a reasonable way to do this.

An Integral Leadership Framework

Mark Edwards (2010) explains very clearly the value of the concept of the holon (Wilber 1995)– a model that says everything is both a part and a whole:

First, holons are useful in both representing complex social phenomena from a non-reductive standpoint . . . Second, theories of transformation, irrespective of the conceptual lenses they employ, will always include some construct that refers to an organisation’s radical shift from one order of function to another . . . third, the holon construct has the capacity to act as a scaffold for displaying other types of lenses (131-132).

Holons are used to show developmental phases, ecological relationships and one that Edwards introduces, the governance holarchy, which “is concerned with the relative organizing power or decision-making capacity that exists between different individuals” (133). The choice of which holon approach to apply in relation to integral leadership and diversity will depend on the nature of the questions we explore. Holarchies can be distinguished by their representation of the individual and the collective. Whether a governance or a developmental holon, each refers to both.

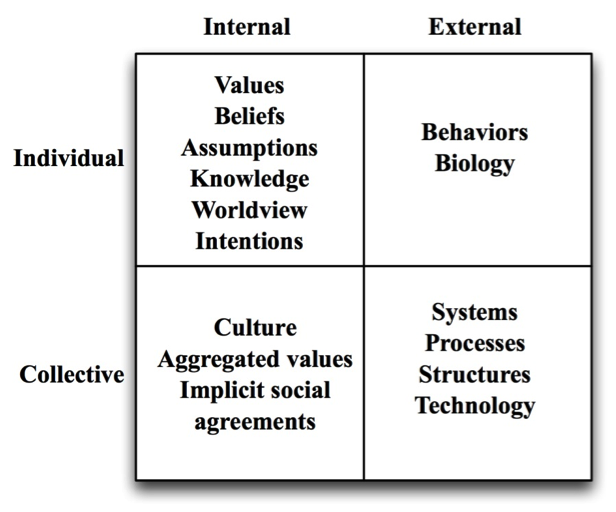

One way to further this individual-collective distinction in relation to Wilber’s four quadrant mapping approach can be represented as follows. Here is an adaptation of Wilber’s four-quadrant map (Figure 1). Note that it includes both individual and collective. I would suggest that this is a useful foundational map, but as we move into the distinction between individual and collective we need a map for each. For each has different, though parallel aspects. Individuals have agency; collectives do not. If the individual walks across a room, all of that individual on the physical plane goes with her. We just can’t be sure about the non-physical, but to the degree that internal variables are biologically anchored, then all of her crosses the room.

Figure 1: An adaptation of Wilber’s Four Quadrant Map

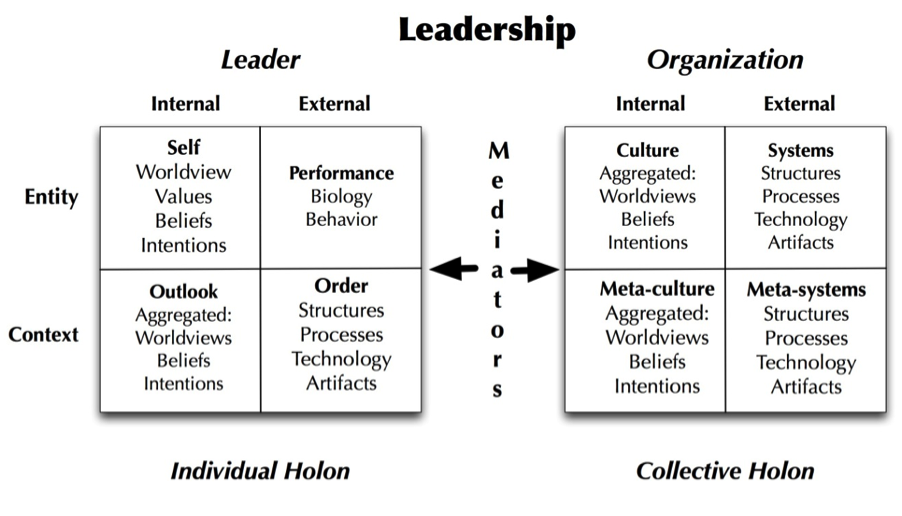

The collective has no such agency. It can be split, moved to different physical locations and still function as a collective, sometimes more effectively. So what are the implications of representing both individual and collective in four-quadrant fashion? Figure 2 offers such a construct that can be used to explore the relationship between leadership and diversity through an integral lens.  Figure 2: Individual and Collective Quadrants (Volckmann 2010).

Figure 2: Individual and Collective Quadrants (Volckmann 2010).

This map of leadership has many interesting aspects. First, it suggests a refinement of the four-quadrant model. To begin with, in the individual holon, all cells are about the individual. That is perfectly in harmony with Wilber’s map. What is different is that the context cells are the context as comprehended by the individual. Outlook is how the individual comprehends the cultural context they are a part of, what they are aware of and not, what is perceived to be relevant and not, what is engaged with and not. The Order cell is about those manifestations of culture, structures, process and so on, that the individual is aware of and interacts with, as understood by the individual or by an observer. This suggests that as individuals in complex systems, our choices for interacting with a system are limited to our understanding, our intentions, our values and so on.

For example, an individual in an organization or other social system will bring his own beliefs, aspirations, intentions and behave more or less in harmony with these. That same individual will understand his cultural context, not just in terms of what he shares with others but in what ways he differs from others in that context. Here is his relationship with diversity. The context boundaries are set by him in defining his world and what he can and will relate to. In the internal context is the monological sense and meaning making processes (Linell 2009) through which decisions are made, maps are imagined and identity defined in relation to the context as understood. In the external context the individual interacts with those physical manifestations of the system that he chooses or that may be thrust upon him. This includes structures, technologies and roles. When interacting with other individuals in the system sense and meaning making becomes more dialogical (Linell 2009).

In the collective holon we find the culture and systems of the whole–all aspects of them, not just those understood or engaged by the individual. Here is where a second or third person perspective informs the context. And the immediate cultural and systemic context exists in a metacultural and metasystemic context. For example, an organization includes a collective sense of the elements of culture within that organization, both what is shared and what is not, as well as a collective sense of structure, technology and the like. The members of the organization have a cultural sense of the larger culture and systems that their organization operates in. These can be economic, social, national, international and so on, depending on the level of analysis.

Diversity thrives or not within the culture of a human system, even when there are many attempts to constrain it through actions ranging from social norms, rules and regulations to barring participation and extremes, like ethnic cleansing. This is why it is important to frame culture as what is shared and what is not, particularly in relation to any human system. The culture of a university is made up of shared values and differences in perspectives, in priorities and so on. Yet we cannot deny that each university has a culture of its own. The same can be applied to other organizations, families, or societies.

At this point it is important to focus on the question of perspective. We can look at this expanded map through at least three lenses. The first would be the individual looking within self or within the collective he is a member of. In this case the lower quadrants of the individual holon and the upper quadrants of the collective holon would correspond. A second perspective would be how the individual and the collective that he is a part are comprehended by someone in relation to both the individual and the collective. The third would be all detected by an observer who is not part of this system. Therefore, when applying this map to any leadership question, it is important to specify perspective.

Mark Edwards’ work on lenses is also relevant to perspective. What exactly is it that we are wanting to understand, to characterize, or describe? This is different through the lens of governance or than of development, for example.

Another feature of this map is the role of mediators in the relationship between individual and collective. Edwards refers to this as social mediation that includes language, social norms and cultural assumptions (118). I find this a bit confusing because those variables can also be found in the Order, Culture and Metacultural quadrants in the holon map. In political and many social systems we can understand media to be mediating by providing selected information and interpretations of events and occurrences not directly observed by all of the stakeholders in that system. It is the means by which the individual interacts with the system and the metasystems at the level of meaning, thereby emphasizing the dialogical nature of sense and meaning making. As Edwards points out, “The mediation lens offers an alternative to those theories that conceptualise transformation as an innate, internal capacity of organisations [or individuals–RWV]” (119). Ladkin (2010) uses Merleau-Ponty’s notion of “flesh,” a construction “capable of providing a means for understanding the dynamic in-between space at the heart of leader-follower relations” (9). These approaches offer additional insights into the dynamics of integral leadership and its relationship to diversity by calling out attention not to just what is happening for each individual or system, but what is happening in the spaces between them.

Integral Leadership

With Figure 2 we can begin to appreciate that the phenomenon of leadership encompasses all of these variables when it is the object of study. In other words, the map in Figure 2 emerges out of an integral theory of leadership that is not reductionist. It is a map that can integrate both the governance and the developmental holarchies. Furthermore, it encompasses the distinctions among leading, leader and leadership. Leading occurs in the individual holon, which in no way negates the relational aspects of leadership. The leader role is defined by the individual, as well as in the collective holon. The phenomenon of leadership encompasses both holons, including all related relationships with stakeholders, as well as the mediation lens. Further, this approach to modeling would provide for the addition of an individual holon for each stakeholder in the leadership occurrence.

All of this has become very complex. It is even more so when the other lenses of Wilber and Edwards are added to the mix. Yet, to do less in the study of integral leadership would be reductionist. This does not mean that everything needs to be researched in order to make a coherent analysis of a leadership occurrence using an integral theoretical framework. Rather, it means that it encourages a conscious articulation of what is omitted and at least some analysis of the implications. Let’s apply this to the phenomenon of diversity in human systems and integral leadership.

Integral Leadership with Diversity

Davidson (2011) pointed out that the challenge to those in leader roles is to leverage differences for organization ends. He clarifies this by stating, “Leveraging differences does not compromise important values and goals for equity and justice… It strongly reinforces them.” While his discussion does not explicitly include the use of an integral theoretical approach, work such as his are tributaries to our more integral perspective taking on issues such as diversity and differences. He summarizes:

Leaders move organizations toward Leveraging Difference by working through the cycle [seeing–understanding– engaging–leveraging–seeing (etc.) differences] relentlessly; encouraging their people to work through the cycle, communicating about the difference activities that have been put in place; and providing encouragement and energy to those involved in leveraging Difference work (188).

This tributary work does not make important distinctions I am arguing for in this chapter. Nevertheless, it does emphasize important perspectives and activities that those in leader roles, CEO and otherwise, can take in leading change. CEOs of companies with any level of complexity as human systems are the individuals in formal positions of authority who may or may not lead in any given leadership occurrence. They may be leading as are others in a transformation change effort or they may be managing constraining variables so that others may lead. Nevertheless, it is likely that they will lead in some sense at some time.

For example, recently a CEO I interviewed was faced with dealing with some differences in working with a board and a room of stockholders. This company could be characterized as having a culture that focused on technology and innovation in mixing expertise and creativity. It is relatively small with fewer than 100 employees, but is nevertheless generating millions of dollars in revenue with a growth pattern of 100% or more per year during a metaeconomy that is highly uncertain. The stockholders may be characterized as having a diverse set of worldviews and value systems with some things in common, e.g., preferring to make money from their investment rather than lose it or see it stagnate. And there are differences among their values, some being more oriented to conservative religious and secular rule-bound orientations; others who cared little for anything but their own profits; others who were excited about the potentials of achieving growth in a young industry; and still others who saw the potential for the company to make a major positive impact on the environment. The CEO was centered in the latter two value sets.

The CEO and the Board were anticipating a highly challenging meeting with the stockholders where there was concern that some might seek to pull their investments. The CEO was charged with doing a presentation that at the least would keep them involved. With an awareness of the diversity of values and intentions present in the room, the CEO proceeded to give a presentation that addressed the diversity in the group by communicating effectively with individuals holding these varied value sets and interests. The result was that no one pulled their investment and the feedback was that all were pleased with the direction of the company.

In this short account, we can find many of the variables that can be considered in an analysis of leadership in relation to diversity. For example,

1) The governance lens: The Board and stockholders represent a power-based governance system that the CEO is responsible to.

2) The development lens: The CEO’s understanding of developmental models made it possible to address the diversity in the room.

3) The individual holon: Each participant could be viewed through the individual quadrants in order to analyze their intentions, worldview and values and to observe their behaviors. Further exploration through research would reveal their sense of belonging to a culture and their “fit” with that culture. They could be observed in how they sought to influence the system through access to the various structural aspects of the organization (middle management, senior management, board, etc.), their understanding and relationship to technology (including the technologies of innovation, problem solving and information access).

4) Lines of development: The CEO demonstrated both cognitive and emotional intelligence in working with the stockholders and the Board. The cognitive pertains to the capacity to comprehend the complexity of perspectives among the stakeholders and to shape her message for each to resonate with. The emotional line of development includes social awareness, as well as self-awareness (Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee 2002). The CEO acted with integrity and authenticity, thus indicating a high level of development of the ethical/moral line of development.

5) Type: The only type variable at play here is that the CEO is a woman and most of the Board and stockholders are men (one woman on the Board). We have no evidence of how this factor contributed to this successful leadership occurrence.

6) State: The CEO reports a focus and presence with the challenging situation with the stockholders that day. And there was some anxiety and stress with so much at stake. She is a meditator, so we might assume that her stress management skills were helpful in shaping her energy toward presence with her audience.

7) Culture: The culture could be characterized as both entrepreneurial and very much about business and financial success.

8) Metaculture and Metasystems: I would include in the metaculture deep divisions related to the economy and confidence in the institutions to address a growing and worldwide economic crisis. Since the products of this company are “green,” I would also include the systems and culture related to sustainability, climate change and ecology.

This is an abbreviated example of how the integral approach to leadership can be used to analyze and comprehend any leadership occurrence. Certainly there is a lot more information that could be gathered with a methodologically plural approach and a metatheoretical or integral framework. All of these variables would come into play in the exploration of integral leadership and diversity.

Implications