Carol Sanford

Carol Sanford served as speaker for Saybrook’s Organizational Systems 2015 graduating class. She inspired the curiosity of our graduates and students as she spoke about her transdisciplinary approach to working with organizations in support of innovation for a more sustainable world. In this interview, we explore Carol’s approach to disrupting organizations, challenging leaders to think differently, expand beyond their current paradigms, and create systemic innovations. As Carol notes in the interview “I became clear years ago that I can get away pushing hard for rethinking, where others could not. I always ask tough questions when I’m talking with someone.” She challenged me throughout the interview and I hope you will appreciate the challenges she presents to the paradigms and language that reside in our organizations and professional communities today.

Nancy: I’m really pleased to have the opportunity today to talk with you and ask you a few questions. I look forward to hearing how your work integrates into this larger context of integral leadership and also how it differs.

I appreciate, as we go through this interview, the opportunity to learn from you and how you present, language and apply your work within the context of some important businesses and changes going on in the world. So thanks for joining us today.

Carol: I’m happy to be here. Thanks very much for asking me, Nancy.

Nancy: You’re welcome. I have a few questions to ask you and to start I want to learn more about your use of the term “responsible” in your two highly acclaimed books, The Responsible Business and The Responsible Entrepreneur which suggest leaders adopt radically new ways of thinking and acting. Can you explain why you chose the term “responsible” and what it means in the context of your work?

Carol: Yes, I can. It was a big long discussion but let me just modify your question slightly. It’s not a leadership book. It is a whole systems change book. I do this work and this way of thinking from the top. I work a lot with CEOs but I work through everyone in the organization. I just want to make it clear that these are really books about how a whole system and particularly a whole business is able to be guided through multiple processes by everyone.

Now, the word responsible, I know a lot of wrestling went on with my publisher. I ended up against my will putting the word sustainability in the subtitle because I know that sustainability is not what I’m talking about but they literally were financially thinking about that people pick the book up and buy it without saying much because sustainability is in the conversation. This was of course the first book I’m talking about, The Responsible Business.

So then I had the struggle to say, how do I get people to think systemically? Because sustainability is not a systems science or a systems practice, even when people put the word system in it. What I wanted was something that evoked what I would call consciousness of a systemic effect which is different than saying, do this, do that to make things better. There are no prescriptions. How do you learn to think about and be mindful of and then become intentional about that everything you do has a systemic effect?

So I was creating frameworks which are different modes we might end up talking about. Then help people really become conscious of, have a different mind at work to pay attention to the systemic effects. Responsibility was the closest I could get to that because even if you compare it something like accountability, accountability comes back into me and what I’m held accountable for. Responsibility is more of an outward into the universe that I touch and where it ripples to and where that goes and how even a small nodal change can change so much.

So I was hoping that I get to have this conversation so that people get the feel of what I’m really talking about is consciousness of systemic effect.

Nancy: I think about leadership in a larger context and how it is tied to the idea of responsibility and how each person takes that sense of responsibility towards creating a better organization, a better future. I really look at it in the sense that every person in an organization can act as a leader to share in creating the desired future.

Carol: And see, again, you’re making it position or person and to me leadership, the reason I pull it away from that is leadership is a very organic process and it fluctuates from moment to moment. It’s something that is more about being a resource to others rather than standing in front of others and saying go this way. My books, all the awards they won were in the general management category. After people read them they said, “Wow, this is really about strategy. Your book is as much about strategy as anything else.” How do you think strategically? It is so much about how you manage, how you redesign work, how you restructure work. And then it has processes which were about leading change and leading culture but not leading people.

That’s why I don’t want people to associate my work with roles of people leading others. That’s why I keep pushing back. Does that make sense?

Nancy: Yes, absolutely. I think that’s a really good clarification. I appreciate that. So when I look at your bio and your website, it notes that through your speeches and your books you relate examples that inspire and instruct business to re-imagine their way of working and change industries, social systems, cultural beliefs and governing practices.

So I’m wondering if you could share a recent example that might inspire our readers interested in learning how organizations can do the kind of work you’re looking at in terms of creating this consciousness of this systemic effect and how they move that out into the world.

Carol: Sure. Of course, my books are filled with what I call case stories. I don’t like the idea of case studies because they’re usually done by other people. There are some case studies done on some of my clients at Harvard. But what I really love sharing are stories that fill up as much as I can all the dark shadow corners of how things happen, and particularly I’m focused on how it is that people with very focused, sometimes quite small interventions, can change the course of history.

Let me say one sentence before I give you an example because I’ll need this as background. I suggest people quit trying to change the world because that’s like, “all right, me, myself at this point in time will change the world?” What really matters and if you look at how many historians have helped us understand history, they go find pivotal points where a person had an intention for something to be really different and the work they did or the contribution they made literally may have shifted a small lever but out of that, something really happened, through time, people go back and say, “Wow, that was a pivotal point,” what Henry Ford did or what Steve Jobs did. They weren’t changing the world. They were changing the course of history because everyone else stepped in line.

Now, let me give you an example of someone that I’ve been working with for about three years now in an effort that is creating something like this shift. I have been involved in a small early part of the story and that’s the Google food system. I’m not talking about the food they serve to employees although it does become a lab for some of action. This is an Innovation Lab about understanding the global food system. Michiel Bekker took on this work using the platform of the Google food system. As many of your readers probably know, in Google you can decide you want to spend 20% of your time on something you think will really matter, but is not on the current agenda. But as Larry Page says to them, the founder of the company, its better have a 10x return and he’s not talking about return to the company; he’s talking about return to the planet, return to society, return to the future.

So when the idea of even the Google Glass came up, the idea had to be not just so that a whole bunch of people who thought this would be clever to photograph other people but it had to be how it was going to change for how people see. Now, this particular lab, the Innovation Food Lab that I’m a part of, the process and the driving energy of it is about changing our relationship to food on the planet. I mean the same way the self-driving cars that change our relationship to transportation on the planet. More of the story of the Google food system is available in The Responsible Entrepreneur.

The teams of people who are involved in this creation are made up of people who are internal to the company and external to the company because you have to have that kind of dynamic energy and you have other people to be constantly perturbing, disturbing the path that you’re on. So we have people who are there from major food labs and university research centers, food innovators, farming and much more.

We have people who are from the University of Switzerland, Cornell and people from Stanford University. We have somebody from Ireland. Then we have a whole set of people who are doing kind of revolutionary things around how they educate people about food. So we have the Jaime Oliver Foundation and several other folks who are working in that field.

You can continue on. We have Stanford hospital. We have a whole set of farm cooperatives along the coast of California. In fact, Google out of this lab has created a relationship with those farms, which are along the coast, with the idea of bringing people to more plant-based diet and helping educate. They start again testing a lot of this internally.

We also now have a commercial CSA between Google, Stanford Hospital and soon several others who agree, just like a home buyer, to be in the Community Sourced Agriculture. You pre-buy before they plant and after the produce grows it goes to the kitchens of all the Google, Stanford Hospital and others and they figure out how to serve something with it. There are conversations between the farms and Bon Appetite who prepares and serves the food. If Bon Appetite thinks they got way too much kale in the spring, they talk. So there are things to work out. We’re building an extraordinary number of different ways of looking at how food is managed.

We are thinking about, “Can you take organic and permaculture gardening to scale?” I mean can you do what the large farms in the Midwest that Monsanto and others own and change so that you can do the same level of work with organic. It may be thousands, hundreds of thousands of people but you’re scaling and making organic and permaculture farming really work.

We have others who are working on the food production process, how it works in schools. There isn’t any area that isn’t being touched. Now, what we’re using is the way to think about all of that is the overview of the work which you can read in The Responsible Business. In fact, everybody there uses, my book, The Responsible Business, and the frameworks that are in it to be more systemic, to reach and get outside of the work that they normally would do; the way they would normally think about it.

There are many test teams and Google does not pay for any of this. Google is the convener, provides a platform. They provide test teams some of which are working on ecological thinking, some of which are working on nutrition and how you transform how workplaces particularly think about how they feed people and help educate them on making good food choices when they go home. You can see there are some ways this is not just a Google type of thing. — It seems like Google does technology things, but their mission is broader. It is working on many things that are important to life. They want to find ways to understand it better and then to promote that knowledge globally.

That’s the way Google is playing. It activated a lab because one guy and then slowly a few others join him wanted to revolutionize our relationship to food, but they needed the kind of frameworks that I have which let them sync up much more globally, more systematically and at the same time practically, bring it fully to ground. So you end up with something like a CSA rather than, a piece of work, like we ought to do more organic food. Let’s go do policy. They want to change things on the ground.

That was kind of long but that gives you one idea of the nature of relationship that working with systemic frameworks and processes can have and the scale you can work on.

Nancy: It sounds like an amazing project and must be exciting to be part of influencing the way people are coming together. Can you share more details about the framework, for instance, in this particular example how the framework helps them move through this process of really thinking together, how to draw the right people into this, where to look, how to challenge assumptions? What are the leverage points for doing this work?

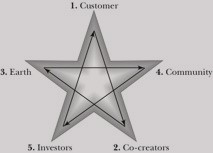

Carol: For me frameworks are an education processes that have specific number of ideas or ways you can bring them together. So I don’t facilitate like in these meetings with Google; I educate. I speak a lot. I engage them in developing critical thinking skills. One of the major — the core framework that I used in The Responsible Business is a Pentad which in Greek means the dynamic related five. So it doesn’t mean five. It’s like a star.

The reason it’s a star is if you think about how you draw a star, the majority of people start at the top. They come down to the lower right and they go up to the upper left and then over to the right-hand side and then back down to the bottom and back again to the top. So you follow the hand that way its drawing and you find a system there.

In the book, I articulate a way of thinking about what might be on each of these points; not the answer to what’s on that point but a starting point for thinking. The top one is customer. It says if you’re in business, you have an obligation to the people who agree to pay you that lets you stay in business and that’s called a customer, a buyer, a user, a consumer. But it means that you are taking responsibility for providing something that gives them a life well lived.

I say that you can’t start any project without asking the question, “what’s core to making sure about the customer here?” Then the next place you go to is what I call the co-creators which are all the people who create the process, the product, the services that go with it which include suppliers, contractors, and what we currently call employees. I don’t like that term but co-creators have created a way for me to say all of these people have an investment in making sure that their customer, user, or buyer has a life that is extraordinarily well lived but they also have a need to feel like every year, at a minimum, every year they are smarter than they were the year before, that they are more able than they were the year before, each of them. And they need to know that they’re contributing directly and how they are personally and uniquely contributing to the customer, consumer or buyer in an unfiltered third-party way, so without any consumer research, without any market research. You have all of those co-creators come to understand how they are making a difference in a way that no one ever told them they needed to but they can see it would make a difference.

The third place you go to in the system is Earth because Earth is in agreement with you. She agrees to invest in you. She says, “Hey, I got some resources here.” If you will ask if the co-creators ask the question, think about that we’re in a reciprocity process and Earth is offering to let us have certain kind of minerals or a certain kind of fiber or a certain kind of liquid resources and in exchange Earth needs to get something.

For me that’s where you enter. Why I don’t talk about sustainability because I want people thinking about the interaction with Earth as an engagement with an ROI expecting return for Earth. Same is true then you go across on my Pentad to community. Each community provides workers. They provide utilities, they provide all sorts of things, but they really expect need. In fact, if we’re smart we’d demand something in return. The major thing that communities need in return is the uplifting and fully integrating of their unique identity.

Every place on the planet has its own essence, its own unique discovery. If you think about your favorite city whether it’s Paris or New York or San Jose or San Francisco or whatever yours is, it is so different than if I — if people say, “Well, you go to Santa Fe all the time,” as you know, Nancy, I go there a lot and they say, “Oh, how lucky.” And I said, “I hate Santa Fe.” They’re “What?” I said, “Well, it’s very different. It’s perfect for some people. The key is that its identity needs to be honored and uplifted and evolved by any community of co-workers or co-creators that are seeking to make something for that consumer, buyer, et cetera.

Now, if you do all of that well, if you really keep your mind on who you’re serving, what difference you’re trying to make and then how co-creators can grow to do that, how Earth can participate, communities can participate, the amazing thing is that your investors which also can be taxpayers, realize a powerful return.

Now, in each of those points I just went through, there are a bunch of other frameworks. So how it is you’d get to understanding customers, much better if you don’t do market research, in fact you get derailed with market customer research, all that stuff, Apple never did that. Google does almost none of it. They have a very different way of trying to connect. But they don’t go out and do market research.

So great companies have figure out a long time ago that the way you understand the customer is the same where you understand your life partner. If they have to give you a list of what they want for their birthday and you don’t know who they are, then you are not building a very good relationship.

So there’s a whole set of frameworks that help you understand how you do that when you don’t live in the same house like you do with your spouse. So there is one master — actually, it’s one of 18 master frameworks that I have. I wrote a book about one of the 18 questions I ask when I go enter an organization and it’s about stakeholders. So that gives you a flavor for what I call an organizing framework. That’s how things are organized. There are others that help you understand how things get ordered, how you understand the nested relationship because that’s how living systems really work.

Nancy: The approach you describe, in my opinion, is an integral approach, working systemically to co-create a better future. I’m curious what draws organizations to your work? What do you think is drawing them to develop, explore and expand on a consciousness of systemic effect?

Carol: Well, that’s a slightly hard question for me to answer in that more than 90% of the people I work with come by referral. So the CEOs I work with, they hang out with other CEOs in various different places from conferences to policy to lobbying and they end up talking about this work. Most of the way they talk about it and so I know it’s what’s attracting is they talk about the results. They don’t even know I would say, maybe none actually know that I’m talking about systems thinking. They don’t come to me for systems thinking. They come to me because I understand how earnings, margins and cash flow work. I understand those really well. Not how you count them but how you create them.

So what they hear is someone like Chad Holliday, who was chairman and CEO and President of Dupont for ten years, will sit and say, we were working with this disaster, this mess called titanium dioxide in my mining operation. And we were creating devastating effects on communities, on mountains. We knew we shouldn’t be doing that but we couldn’t figure out how to get out of it. We kept having all of these problems about that we should be financially proving that it was worth bringing in any different way of thinking.

And then I had a conversation with Carol and she never even mentioned responsibility or systems or anything to me. I’m sure he would say that. And yet she started teaching us how to think about how to build really great businesses. The minute we start working on systems, we started innovating and she started with helping us understand how earnings, margins and cash flow get created.

So now you’ve got a CEO listening, right? Oh, okay, somebody who actually works off the financial side.

One of the things she taught us was margins really happen because of innovation and product distinctiveness. Until you actually have everything you’re working on drive toward that, you will not really get margins that are greater and growing compared to what others get. So now you’ve got the CEO which is usually who hires me or a business unit leader, and want to be able to defend that they’re doing that.

So Will Lynn is an example, when I came in to Kingsford Charcoal 30 years ago now, they were making marginal returns. They had a terrible record of injuring people, of polluting things. What they had to do was figure out how to change things. Will Lynn heard about me. He heard the thing that I said which was that if you could grow people, you could grow a business.

Again, there’s not anything quite systemic there but that’s a little closer to, oh, if you do this, it affects that. It struck what I would call magnetic scenarist in him. Magnetic scenarist is this philosophical idea that some people are closer to having you on the surface and for some it’s more hidden of wanting to do something that really matters. He had been treated really poorly as an early employee in many of the jobs he had. He never graduated from college. He was a math whiz but he only went to college one year. What he heard was this idea about helping people and how it was that you could turn them around. So actually, both of those things could have been worked on some other way. No one hired me to come in to do systems thinking. They hired me to change the course of their company and how their people were involved in it. Their cash flow grew on average from 40% to 65% a year in industries where it was always single digits and mostly below 5%. Both of those examples I gave you were very low.

What they hired me for was to do what a company needs to do and it changed how they thought because of the way I worked with them. I worked with Dupont for years including the titanium dioxide group for three years and we created a proprietary technology which still owns the industry that cleaned up all the mining operations, cleaned up all of the destruction and even the ways they work with people because that was just educating all the way along. I mean it’s why I don’t go in with the program. I never go in with the program. I go in with an education platform that says, I’m going to teach your business people how to be business people.

So I know that’s probably not the answer you’re expecting. I create systems thinkers without ever telling them. That’s what I’m going to do and without them thinking that’s what they have hired me for.

Nancy: Well, I think what I hear you say is really you’re tapping into what their needs are. You’re able to meet them in their orientation, their current thinking and their language.

Carol: Well, actually I don’t do that. I do not meet the current orientation, the current language at all, like people say start with where they are. Nope. I’m disrupting from the minute I arrive. That is something that — I mean I could not be, right, Nancy? You’re laughing but I would not want people, I would not let them think that I agreed with them for them to hire me. I want them to know from the beginning that they are going to be really challenged.

Now, most of these people who have been CEOs or business unit leaders have been used to being challenged by coaches. But they never felt like they got much from that challenge in business returns. It always felt like a personal battle. What they find with me is they got smarter and more focused. I became clear years ago that I can get away pushing hard for rethinking, where others could not. I always ask tough questions when I’m talking with someone. And my work mostly comes by referral. I put up large encompassing frameworks and then I show them where what they’re asking for is a small part of what they need to look at and what they are asking for is a small little corner.

Most people think too small and in parts. They don’t know how to grasp the whole. It’s in the kind of thing you need to be thinking about but actually you’re asking the question in too small a way. I move them to ask the question in regard to a bigger context. Does that make sense? So I said so we’re going to answer that but if you hire somebody who goes directly after what you say you need and where you are and even how you think about it, it will take you so long, if you ever get there.

So I want to disrupt you from the beginning, but I don’t tell them I’m going to work on systems thinking. The first time I used systems thinking is when I use the framework to show them what it is. I don’t want to use it just through words. So I use frameworks and interactive engagements to disrupt where people are and then they decide where they want to hire me.

Nancy: I see you working in a nested system where you recognize the needs of the organization, and get people in the organization involved in recognizing those needs. I hear you saying that an understanding of systems comes through using the frameworks you created and also supports disrupting the system. It is through learning something different, challenging their thinking and practice that leads to change.

Carol: There is one other word — I am sorry. I just have to point out this language because this drives me nuts. This is what I do to them when they bring me in. I would say, all right, so I don’t work on needs. I don’t care what your needs are. They’re irrelevant. We’re not going to find them. We’re not going to work on them. We’re not going to find any problems. We have no conversations about issues, problems or needs.

What we’re going to start with is what is it that is really the essence of this company when it was founded. With Dupont, when we did that, we’re going back 204 years because nobody had talked about it since the E. I. du Pont had been gone and almost 200 years had passed. This was Chad Holliday. So I said we don’t start with anything that you can see in current existence. I ignore existence. And what we’re going to work on is what a business looks like when it’s working at a whole and complete way and it starts with essence. Most people really misunderstand what I mean by essence. It is not purpose, it’s not vision, it’s not mission. It is something that was in the founder when he was born or when she was born that comes into existence in everything you touch.

So I start with potential. I don’t start with existence. I don’t start with needs. I don’t go in and figure out any of that. I don’t do surveys. In fact, I write papers and say do not do climate surveys. Don’t do anything internal. Don’t help them figure out what their biggest problems are. Instead, figure out what their potential is and then move everything toward that.

To me that’s the basis of real systems thinking. Most people I think have a machine view of systems thinking that comes out of systems dynamics that was manufactured at MIT using artificial intelligence. Jay Forrester worked on artificial intelligence. And he didn’t want to publish it. He said, “Don’t ever use this on living systems. It’s only about machines.” It’s now the major thing that’s taught as systems thinking. And then there are people who have taken innovations off that and created biomimicry and some other processes, all of which are still machine paradigms of living systems.

So I have to confront all of those things, disrupt them, disrupt all the stuff that comes out of the study of lab rats, thinking that is how humans exist. I think it’s a human potential paradigm and it has influence many fields, even integral leadership. I just think it is incomplete. So I don’t ever start with where people are.

Nancy: I appreciate that distinction. Maybe you can say a bit more about what you see as incomplete in terms of how the integral perspective has evolved.

Carol: Well, I’d rather not spend a lot of time trying to talk about integral. I think there are people like you and the others I know who are really striving and working and developing and growing. I’ll say just one thing, that there are different paradigms out of which similar intentions come. Most of the work that is happening right now with people who have really high intentions and can see that something needs to change has been influenced by the behavioral science and humanistic paradigms. People coming out of those schools are working with work redesign and somehow think it’s brand new.

For example, nearly 50 years ago, the year Arthur Koestler’s book came out on Holarchy, we created a whole system in Procter & Gamble called Holarchy. It didn’t look exactly like the one Zappos is working to create, but it has some similar frames to it. Over time I realized it was based solely on the human potential movement and there was an incomplete understanding of how humans work and it was very much contaminated with the study of behavioral science and humanistic science. I mean contaminated in the way that it had a mixing and matching and a stirring up, not starting with how is it that humans work when they are living their purpose. They’re not living their role inside of a larger purpose.

Every time you hear me say, “Nope, that’s that one I believe,” usually what you’re running into is a paradigmatic conflagration where something has been collapsed and you’ve got machine paradigms, behavioral lab rat paradigms, human potential paradigms, and rarely do people have a real understanding from living systems science, how living systems not just humans, but humans nested in living systems work. I can catch it really quickly by languaging.

So I am not re-languaging just for the fun of it. I’m paradigm rearranging. I’m making paradigms conscious. So the word “need” literally comes out of a behavioral paradigm. The rats need to get to the food on the other side, so you use that driving base nature and add little bit of the human potential in it and you have Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which is a frame that it drops into people’s head. But it’s not completely a living systems paradigm where you can see the nested understanding of a role that humans and each other entity in a living system play.

So let me give you a really quick example of that because that’s a complex thing, but it’s one thing that I teach my clients and my change agent groups over time. A tree puts out tips and squirrels eat that. They defecate and create fertilizer that gets mushrooms really alive and working and growing, feeding the roots but then feed the tree.

Now, one of the things that Kat Anderson who works with and studies native peoples found is that native peoples figured out this process of a tree being healthy and they understood and joined with how it was you could build a forest and what we know is the forests that are in the North American northwest cognate of our continent were nourished and farmed with the help of humans because humans understood they had a role. It’s not wilderness. It’s actually managed forest.

If you don’t have that thought, then you have a paradigm that’s incomplete and you tend to work with just a human potential paradigm which just drops out ecosystems completely and it also has very little understanding of the dynamics of macro psychology because the brilliant teachers we had and I have so much admiration for Carl Rogers and Virgina Satir and the folks who founded the human potential movement, but they were incomplete in that they didn’t understand humans were nested in living systems and that the evolution and fulfillment of their role in that ecosystem was important.

And then you get really incomplete when you get down to behavioral stuff and you have incentives, rewards, recognition, all that stuff which comes out of the behavioral study of rats. The most incomplete are obviously people who collapse only into machines which is where the MIT systems dynamics come from. We have hundreds of thousands of people who think it’s the highest level. If you’re only there, you’re really in trouble but most people mix and match of at least three of those paradigms.

Good grief. I feel like I’m teaching a course.

Nancy: I feel like I could really learn a lot from hanging around you. While I have been working on my own approach to disrupting the prevalent paradigms, I can see from speaking with you that I have much more to learn and become conscious of in my languaging.

Carol: Well, one of the things that you told me you were going to ask me about was the transdisciplinary approach which I know you hold as well.. I’m actually talking at this point without talking about how it is that I go about disrupting me all the time because one of my primary guidelines is I must disrupt me. So here is the guideline I give myself. I can never ever even once present the same material in exactly the same way that I ever have before. That’s exhausting sometimes.

You get your notes and you say, “Well, where was that handout I did. I should use that. I use no handouts in the exactly the same way. And I can’t just go change it.” I said, “Okay, well, I change the rules.” I have to say, “Who is this group in front of me? What is it that their potential is calling for? They probably can’t even articulate that. But I’ve developed the ability to see things most businesses can’t see. They could never tell me.

But I can see where it is I need to go because of the ordering and organizing frameworks I’ve built capacity with. But that ability to really be able to see what it is that needs to be seen and work from that is a really important part of being a part of this work. Then demand, if you say I can never use this again, then you’re listening all the time for what to disrupt me. In order for me to disrupt others, I have to disrupt me.

Nancy: That’s great. A great way to really keep one’s learning always happening. It is easy get in a rut of saying the same things, using the same work we’ve done over and over again.

Carol: Right.

Nancy: So a couple of questions have come up for me and one is as you work with organizations and you really help them see things very differently. They begin to adapt. They shift their paradigms or integrate more of these ideas —

Carol: Or they become conscious of their paradigms which is my intention.

Nancy: Okay.

Carol: Yeah, I know we have to shift paradigm. I want people to be conscious of the one they’re in. It’s a moment how they’re seeing things from it. Anyway, continue.

Nancy: So do you see those organizations really being able then to take that consciousness of the paradigms and start changing, radically changing the structures and the supporting structures? You talked about how many of the supporting structures in organizations are grounded in the behavioral science paradigm which is just unfortunate.

Carol: Well, there are things about the human potential paradigm which are excellent so I’m not saying throw the baby out with a bath water. But yes, the answer to your question is what I’m working on is not a particular way of running a business so I don’t walk in and say structure your teams this way. I give them high order principles, a lot of case stories and a framework for developing it.

So nobody ever looks alike because what I’m wanting is their ability to think in a creative way, not adopt wholesale like Zappos is doing. Something somebody says, this is how you structure work. I look at what their structure is, and I think, oh my God! This is going to kill their business. It’s going to kill some of the major things they stand for and the really sad part of it is that it is out of really good intentions, but it’s out of a misunderstanding about the paradigmatic shoes they’re standing in.

So I am so excited when I watch people like Jeffrey Hollender who has a new business now. He is long gone from The Seventh Generation and has created a new company called Sustain which produces condoms that are marketed to women and that are sustainably created and made healthy and non-toxic which they need to be given where they get put. Pretty bad things can happen when you’re using toxic products.

Jeffrey is using what he learned and he says to me — I just talked to him again a couple of months ago and he said, “you just help me change how I see everything. It changed how I think about strategy. It changed how I think about business models I build. It changed how I think about partnering. Because I keep asking in the conversation when I’m proposing something, what framework am I thinking through and what paradigm am I thinking through? How am I structuring how I’m listening to them? Can I educate them?”

He even went into Walmart and worked with Lee Scott some years ago, and I got to be with him part of that time in helping educate how they thought. So it sticks because it’s like one of those things once you shift, and you know that you don’t want to find the right answer but you want to find a way to think about things that you’re constantly keeping alive, you can’t not do that. In fact, a few people who have been in companies — probably a lot of them but I hear from a few — who leave a company and go to work thinking, “Well, I’ve done all this stuff I can carry over,” don’t understand that it’s an education process. You can’t go just layer it on. It drives them crazy because they can’t get people to be reflective on the level of thinking that they’re bringing, the epistemology they are bringing, the cosmology that they’re bringing, which is like a paradigm. Even what they think about, the ontology of humans and what is meaningful for them.

So it does change it because they become scientists in the sense that they’re looking at themselves and others and how it is that they’re creating. Do they have the ability to evolve or do they just have a program that they’re now stuck with?

Nancy: Absolutely. So they’re really thinking totally differently.

Carol: Yeah, they are thinking not “thoughting”. That’s David Bohm’s famous phrase. I just love it. They’re not thinking but using thoughts they have had forever and just continuing to spew them out. They’re actually not watching their thinking. They could open up their own thinking by watching their thinking.

Nancy: Yes, I agree that creating new thoughts is really the work we need now. I think that many of us are trying to tap into the different approaches that are out there while becoming more conscious of the paradigms we’re in and of the systemic effects of how we think and what we do with that thinking.

Carol: Another place of responsibility, right? We’re responsible for the effects we create with our thinking.

Nancy: Absolutely. Since we only have a few minutes, I wonder if you could just say a little bit about your SEED Communities because I think this is a very exciting way to begin to take this work just outside of the organizational context and begin to educate potential leaders, entrepreneurs of new organizations.

Carol: Yes. This is seed-communities.com and we won’t get very far into it, but I have three different kinds of SEED Communities. The oldest is about 40 years old which are change agents. This is the process of taking people who are in different disciplines in life and feel responsibility for the evolution and growth of those disciplines and teaching them how change actually works, how thinking works.

Well, a lot of the kind of things we’re talking about plus a lot of much deeper stuff than that, it’s based on multiple disciplinary learnings. Each of these, including the change agent one, meets in four different cities, four times a year. When you join, whether it’s Seattle, San Francisco, New York and Boston, you can attend all 16 if you want to do that. I have people who work on the education committee. I have senior faculty out of Stanford University, chairs of departments.

I have people who are out of MIT and out of Penn State, huge number of Penn State, many of them working in the architecture and construction world. But I have the education people then I have a whole another group of people who are working on education in the primary level. I have people who are working as architects trying to change how people think about architecture. I have a large number of people who actually are just directly like consultants or something, usually to one field but not only — I’m trying to think even who else is in there.

So I have all of these different disciplinary — oh, I have a group of artists which is really fun, which are actually beginning to make a living quite well with their art and are thinking about how our thinking -can help people see their consciousness or lack of consciousness or levels of consciousness through art, through music, through performance art.

They meet with me and they show up and they sit and they learn together and by cross-referencing. I also do webinars with them in between. I’ve got three different levels. I’ve got people who come just because they want to take it back into their own work. I’ve got people who want to take it into other people’s work, and I’ve got people who are part of Carol Sanford Institute who I take with me when I go into a company to work. So they actually work live learning how to do this.

I’ve got also an entrepreneur set of communities. Those are in Mexico City and New York. We may be starting one in Philly in October. We’re still looking to see if we’ve got enough to build it. I have a similar kind of thing with the University of Washington where I have a program that ran a joint partnership. They bring individuals into the course but they work in community for many years. They have one year of getting a certificate which is 12 days over that period of time and about 20 hours of webinars.

There are many different ways I’ve been working to try and take people who are working individually but need to be in community because you really can’t grow and think unless you’re in an ongoing community.. There’s no curriculum. They don’t know what to expect when they show up. They show up in many different places and they watch me introduce the subject in a radically different way. It begins to have them understand why we don’t want to make a program out of this.

I have people who have been with me for 35 years and then I have a few new people who started last week. So it’s like 200 people now. I’ve got a few in Europe. I’ve got one program I run in Northern Europe of folks like this too who are a mix of change agents and entrepreneurs. So that’s kind of the SEED Community.

I did want to tell you the disciplines we use because I think it might be fun for people. Is that okay?

Nancy: Absolutely.

Carol: All right. We do a lot of work with different disciplines, all of them are what I call value adding process disciplines” which means that they’re really looking at something alive and we’re building on and adding to it, compared to making it dead like a value chain and supply chain. But is it really alive? One of those living systems communities is the life sciences, particularly evolutionary biology. Another is the science of complexity but we go back to primary sources because the people who are talking about the science of complexity nowadays are using translations of the original science.

I read books that are full of math and physics. I studied with Eric Jantsch when I was at Berkeley. He brought Ilya Prigogine in all the time. So I’m going directly to the sources of the scientists who understood it. We do a lot of work with consciousness science including some brain science but a lot more indigenous sciences. I am 1/16 Mohawk. So I’m still very connected to indigenous sciences myself.

We work a lot at various learning processes like the epistemologies of how they play out and why they play out that way, where do people form the idea of how they’re going to learn and how they can learn. I do a lot of work with philosophy of science which is where my work with paradigms comes into play. I do a lot of work with mental linguistics. I did a lot of study on mental linguistics and how it is that it affects how we think and represents how we think.

And then the wisdom traditions but particularly the threads that run through them, so Mahayana Buddhism, Sufism, Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. I spent time and tons of charity working with communities like that. That’s the third. Then Christianity and Socrates are the five spiritual wisdom traditions plus the other interdisciplinary options. Is that enough?

Nancy: Well, I think we could definitely say that you are bringing many interdisciplinary threads together.

Carol: Yes. And I do look for threads. It’s not like everything in it is tradition. I’m showing the thread that runs through those. Within our school we found probably eight or ten common threads that go across all of those. That tells us there’s something significant there rather than one tradition.

Nancy: That transdisciplinary approach is really at the heart of the integral community.

Carol: Right, right. There are places we do overlap. We’re just keen to take them from different philosophies of science. And so I’ve had lovely conversations with folks because of that knowing that we have about Sri Aurobindo and The Mother. Each of us learns something from that. It’s great.

Nancy: Well, most valuable in this learning process is exploring how our different perspectives come together in ways that can expand all of our horizons and support our continuous learning. I really appreciate the time you’ve taken to do this interview today, Carol.

Carol: My pleasure.

Nancy: I’m sure our readers of ILR will learn a tremendous amount from what you’ve shared with us today. So thank you so much.

Pingback: Esencia y potencial. – Secano sin sequia